It’s not uncommon for a television comedy to lose steam as the years go by. Sometimes it finds a second wind, and usually it does not. There’s nothing remarkable about the fact the The IT Crowd went from critical darling to such a mess that creator Graham Linehan chose to pull the plug rather than drag it on any further. What is remarkable is that it only took 24 episodes to get from that dizzying high to a show-killing low.

I rewatched the fourth and final series recently, and was struck all over again by how lifeless and dull it felt. It’s nothing to do with the performances as the cast makes the best of what they’re given, and any laughs that we do get come from an effective delivery rather than any particular cleverness in the line…there just seems to be a sloppier approach to the comedy, and perhaps an ultimately-destructive assumption — however correct — that the cast could be relied upon to make up for any shortcomings in the writing.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the series’ de-facto finale, “Reynholm vs Reynholm,” which takes ostensibly humorous detours into a silly restaurant. Series one’s “Fifty-Fifty” did the same thing, and I thought it might be interesting to focus only on those detours, and discuss their levels of success.

The Setup

In “Fifty-Fifty” the setup is simple, and completely organic to the plot. (Or, in this case, and in notable contrast to “Renholm vs Renholm,” the plots.) Specifically, a restaurant is recommended by Moss, separately, to both Jen and Roy.

Jen is looking for a nice restaurant in order to make amends for lying about having specialized knowledge of classical music — a lie which leads her romantic interest to use her as his Phone-A-Friend when he appears on Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? — and which, of course, causes him to lose.

Roy is looking for an edgy restaurant with a tough atmosphere, because he has a date with a girl he met online, during an experiment he was conducting to see if women are actually more attracted to men that treat them poorly. He creates an antagonistic and disinterested persona, and is looking for a restaurant that will make him seem even tougher for hanging out there.

The restaurant Moss recommends to each is called Mesijos…or, at least, that’s how Moss pronounces it. Here, the visit to the comedy restaurant comes late in the episode, well into the third act, and it’s organic to the twin plots we’ve been following all along.

In “Renholm vs Renholm,” there is no plot by the time we get to the restaurant, because barring a brief introductory scene during which Douglas discusses his ex-wife and is then immediately accosted by his ex-wife, we’re dumped right into it.

This, in itself, is not a problem. There is no requirement, unspoken or otherwise, that every location the characters visit must be fully and completely justified by a logical progression of the script. That being said, there is some sense of satisfaction when that visit is justified, and arises naturally out of the story we are being told…especially when compared to “Renholm vs Renholm,” which has a character we’ve never seen before barging through a door, Matt Berry making a funny face, and then an immediate and unexplained teleportation to a new setting.

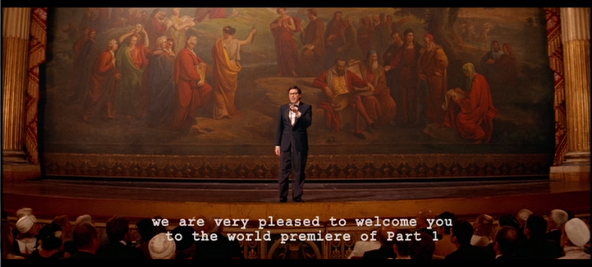

When we arrive at the restaurant in “Fifty-Fifty” it’s less abrupt. We know where these characters are going, we know why they’re going, and we know what they hope to accomplish by going. With such narrative groundwork laid, we get an immediate laugh when we see the restaurant for the first time, as in the screenshot above. It’s neither conducive to Jen’s apologetic dinner nor Roy’s attempt at passing himself off as a cold-hearted bastard.

But what’s more, it’s not an unfair subversion. What’s happening here to Jen and Roy is not just a comedy writer putting his characters through hell, it’s absolutely true to what we know about Moss, who recommended the restaurant…more on which later. Suffice it to say that this choice of restaurant — and therefore the episode’s reasons for taking us there — is a natural outgrowth of the story we’ve been following. It’s a bad decision for the characters, but a sound one for the writer.

“Renholm vs Renholm” dumps us into this comedy location for no narrative purpose whatsoever. It simply wants us to laugh.

What’s so bad about that in a comedy program? Nothing; it’s a great impulse. Where this scene falters (or these scenes falter, rather, as we pay not one but three visits to this restaurant) is the fact that it’s not really funny.

In “Fifty-Fifty” we cut from measured conversations about where to go for dinner to a loud, frantic, busy scene that’s immediately funny out of sheer contrast, and continually funny because the madness only ratchets up from there. In “Renholm vs Renholm” we cut from Douglas having one measured conversation about his ex-wife to…Douglas having another measured conversation about his ex-wife.

There’s no contrast. As you can tell from the screen grabs, there’s no shock here. One neutral colored room to another, one woman to another, with Douglas reacting in no particularly humorous way to either conversation, unless you count each of the times the script wants him to make bug eyes.

There’s no reason for Jen and Roy to go to that restaurant in “Fifty-Fifty,” so the script makes sure it creates a reason. There’s no reason for Douglas and Victoria to go to this restaurant in “Renholm vs Renholm,” so the script doesn’t bother discussing it and just hopes we won’t notice. There’s a huge gulf in writing quality there.

The Joke

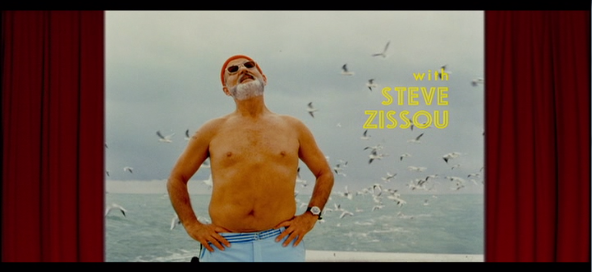

The joke in “Fifty-Fifty” is evident from the first frame, seen above. Moss has mispronounced “Messy Joe’s,” and both Jen and Roy are stuck on their respective dates in a wholly inappropriate restaurant.

This steadfast mispronunciation is in-line with Moss’s character — he’s similarly misguided when it comes to pronouncing the word “tapas” — and the fact that he both enjoyed himself at this restaurant and doesn’t see that it wouldn’t be appropriate for his friends’ needs suits him as well. Moss is severely lacking in social skills, and his perception of the world around him occurs through psychological filters that the rest of humanity simply does not have.

The sign in itself makes for a great joke without need for comment, and the snap-cut to the madness inside reinforces just how ludicrous the scene is…and yet, it’s not an inherently funny place. There are families there enjoying themselves, after all. The restaurant in itself isn’t a joke…the situation is the joke. Many background characters are perfectly content with their visit to Messy Joe’s. What makes it funny is that the foreground characters are not, and that’s an important distinction to make. The comedy comes from the contrast, not from the fact that Messy Joe’s exists at all.

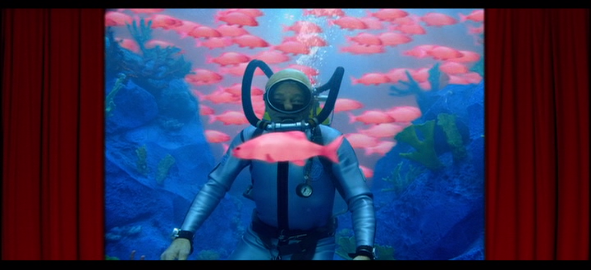

In “Reynholm vs Reynholm,” however, we find ourselves at the other end of the spectrum. Again, we find ourselves oriented by a still frame of the sign, but if anyone can tell me how “The Flappy Duck” works as anything other than a limp — ahem — dick joke, please do so.

Messy Joe’s manages to function as a series of jokes immediately. The name of the restaurant borne of a mispronunciation, the logo giving away the type of establishment it is, and then the immediate cut to the clowns and screaming children.

The Flappy Duck on the other hand doesn’t get a logo. Neither the sign nor the building have any character whatsoever. It’s a phrase that I guess somebody might chuckle at, somewhere, but The Flappy Duck as a name has nothing to do with the restaurant itself, which appears to be a riff upon trendy establishments with non-traditional dining experiences.

Perhaps, then, The Flappy Duck could use some more personality in its set construction, because the joke doesn’t land. The wine looks like milk, which could lead to some kind of joke, but instead we’re just meant to laugh at the fact that it doesn’t look like wine. That’s not effective comedy, that’s not something that says anything about the characters, and it’s not even a joke with a clear target. I suppose I could hand you a cracker and say “Please hold my shoe,” if I really wanted to, but I don’t suppose anybody would be singing the praises of my wit afterward.

In the first scene at The Flappy Duck, Douglas is eating what looks like a small radio and Victoria has a piece of somebody’s lawn on her plate. Only it’s just sitting there. The actors don’t engage with it, they don’t comment on it, and they don’t see anything strange about it. Whereas the Messy Joe’s debacle was a conflict borne entirely of — and heightened satisfyingly by — immense contrast, The Flappy Duck just has people talking quietly about not-particularly-funny topics while not-particularly-funny things sit baldly and blandly on their plates.

That might work in a Spot the Difference puzzle in the Sunday paper, but it doesn’t make for a particularly well-constructed scene in a sitcom.

“Fifty-Fifty” keeps the jokes coming by simply highlighting how uncomfortable the characters are. Most great comedy is on some level generated from somebody’s discomfort, and that’s why the visit to Messy Joe’s is funny. Having Douglas and Victoria — and later Jen and Victoria — sit comfortably at ease with whatever minor absurdities may be sitting on their plates isn’t funny. That’s a lesson that The Simpsons seems to have forgotten as well; when the family doesn’t fit in, it’s funny. When the family not only fits in but qualifies as global celebrities with people of great fame and power at their beck and call, it’s not.

Jen is here in order to apologize to the man whose chance at fortune she ruined with her lies. All around them balloons pop, children bleat and sparklers fizz. These two characters don’t need to tell jokes, because — all at once — they are the jokes. The world has turned and left them in a position of ridicule. They became, ironically, the most ridiculous thing in Messy Joe’s.

Ditto Roy. His ill-conceived bid at being taken for a tough guy may have been destined to fail, but by meeting his date in this environment it’s already unraveled before it even gets started. When a child next to him dances around with his shirt over his head, Roy needs to call a clown in to keep the peace. When a waitress hands him his milkshake, he too politely thanks her for it. These are jokes that come from characterization, and ones that rise organically from tight and skillfull writing. This scene didn’t need to be set at Messy Joe’s in particular, but what Linehan managed to do was graft one great and escalating joke onto a situation that was already funny in itself. In short, he took a good thing and made it better.

At The Flappy Duck, he’s making it worse. Bored, perhaps, of the aimlessness of this dinner, he has Victoria rise and address the camera like a character in a soap operas. Of course, the other diners wonder what she’s doing, and that in itself is a pretty good joke. It’s oversold here by having Victoria engage with the other customers and ask what they’re eating — drawing attention to an absurdity that she should probably not be aware of in order for the joke to work — but it’s something.

It’s also, however, not related to the setting at all. Whereas the Messy Joe’s stuff could have taken place elsewhere, it’s funnier because of where it’s set. The Flappy Duck material could still keep us in Douglas’ office, and work no less well for it. In fact, it might work better, as our presence at The Flappy Duck adds only confusion to the scene, as we keep waiting for a payoff that never comes.

Douglas does have one line — announcing the arrival of their invisible desserts — that makes a token stab at tying the action into the set they’re sitting on and probably wondering why anyone bothered to build, but true to the slapdash feel of the script nobody comments on this, and it lies there like a non-sequitur. It’s a singular attempt, at last, to find some comedy in The Flappy Duck, and nobody cares enough to see it through.

It’s not that the Flappy Duck sequence(s) couldn’t be funny, it’s that the writing isn’t working to make it funny. The attempted punchline here is that Douglas introduces the head chef to his wife while she jacks him off under the table with her foot. It’s a chance for Matt Berry to make yet another funny face but it would unquestionably be more interesting to watch if they gave that face something funny to say. Which leads us to the biggest issue…

The Writing

The distance between these two examples in terms of writing quality is staggering. Despite both episodes being penned by Linehan, “Fifty-Fifty” seems to have an innate understanding of why its ideas are funny, and it exploits that knowledge to mine the comedy more deeply, efficiently, and effectively. “Reynholm vs Reynholm” doesn’t seem to know why it’s supposed to be funny, and it relies on the actors to sell an idea that feels like it was never fully conceived before the episode was shot.

At Messy Joe’s, the jokes don’t stop after the initial reveal. Rather we move logically along the comedy scale, compounding the situation until it hits its breaking point. From the initial reveal to Jen sitting apologetically across from her date to a mariachi band attempting to serenade them to a clown pointing and laughing at the loser who blew his shot on Millionaire, every moment feels like a step forward for the plot, for the characters, and for the comedy.

“Reynholm vs Reynholm” spins its wheels without any clear destination in mind. Its singular plot is about the reappearance of Douglas’ ex-wife, whom he remarries and then wishes again to divorce. For no reason whatsoever, they discuss this at The Flappy Duck. For even less of a reason, Jen also meets Victoria there to deliver the news that Douglas wants a divorce. And then for no reason whatsoever, the four main characters gather at the end of the show to drink milky wine and celebrate the fact that they limped to the end of the episode and never have to film scenes for it again.

“Reynholm vs Reynholm” flails wildly for something to cling to, with references to past episodes being tossed out in the hopes that they’ll get a chuckle out of recognition and the long-overdue return of Richmond, but these last-ditch acrobatics are unsuccessful in distracting us from the fact that this is an episode about a character we’ve never met, which doesn’t seem to have any real stakes for the show nor any basis in reality, and which is resolved in a deliberately unsatisfying manner.

Far be it from me to suggest that we have to care about the characters in order for the jokes to land, but I do think that the show has to at least pretend that it thinks we care, and by this point Linehan no longer feels interested in that.

Nobody at home will ever be moved to tears by the plight of Moss and Roy — let alone Douglas — but the show needs to at least keep up the illusion that somebody might. That’s the only way it can successfully generate comedy from the awkward situations in which these characters find themselves. Admit that we shouldn’t care and disbelief is shattered: we suddenly don’t care about them, and we’re going to wonder why we’re watching.

“Fifty-Fifty” works because it maintains the illusion that these events mean something. When Roy is frustrated by women and attempts to demonstrate how shallow they are with his experiment, it means something. When he becomes sucked into that experiment himself and tries to date the woman who fell for him, that means something too. When Jen lies about having a knowledge of classical music because she wants to impress a handsome stranger, that means something. When she disappoints him and reveals the truth, that also means something.

It all builds toward a climactic clown beating that sees Roy’s date falling for Jen’s date, demonstrating that — in this case at least — Roy’s hypothesis was correct, and Jen’s paid the price for her falsehood.

This isn’t destiny that brought these plot strands together. This isn’t fate, isn’t luck, isn’t karma. It’s writing. And it’s the work of a writer in command of his craft.

By “Reynholm vs Reynholm,” that sort of command is no longer felt. Episodes feel like strings of set-pieces and unrelated moments. Some of them get laughs, some of them do not. That much is common in sitcoms. But that’s exactly why we need a thread to cling to…something to follow along. Some gesture on behalf of the show that says, “If you’d like to care about this, or even pretend to, for just half an hour, we’ll make it worth your time.”

When “Reynholm vs Reynholm” dumps us time and again into the humorless Flappy Duck, it’s an act of narrative desperation. There’s nothing Linehan can think to do with the main cast or setting, so we’re transported to this new location with a new character in the vague hope that, somehow, it will pay off.

But it never does. And when Victoria eats a knife even though they aren’t edible, it’s as though Linehan forgot that he already made that joke earlier with Douglas and the menu. It’s not a callback, it’s not a fulfillment of foreshadowing, it’s not thematic resonance. It’s desperation…or at least that’s what it feels like.

There’s something to be said for going out on top. With The IT Crowd, Linehan didn’t do that. But by choosing to end it before he dug too deeply into mediocrity, he did the next best thing.

It would have been nice to have a fourth (and fifth, and sixth) great series, but that wasn’t in the cards.

Oh well. We’ll always have Mesijos.