In 2009, Thomas Pynchon released Inherent Vice, and oboy did it feel like we’d slipped into a parallel world. The famously oblique and reclusive author had not only attached his name to a straight-forward (relatively, natch…), overtly comic detective novel, but he narrated his own trailer for the book, compiled a playlist of songs (many of them non-existent) for Amazon, and even, for the first time ever, optioned the rights to a screenplay.

Oh, and he makes a cameo in the film. You know…the guy who refused to be captured on film of any kind and who once wrote the line “A camera is a gun.” That guy.

What’s more, this all came not too long after a pair of appearances, as himself, on The Simpsons. Why was the world’s trickiest living author (or most authorial living trickster) toying with public life all of a sudden?

There’s no answer. At least none that I’d have. None that you’d have, either. But the process of writing and publishing Inherent Vice seems to have shaped, however briefly, another version of Thomas Pynchon. A bilocated, more visible double that had his own agenda.

Whatever it is that sets this book apart in his mind…well, let’s just say it’s fun to think about, but nothing we’ll ever know. So what we need to do instead is focus on what we have…the first film based on the writings of a man who writes the unfilmable.

And I’m going to walk you through the trailer, telling you everything you’re seeing without really seeing it, ya got me? Feel free to fill in my blanks; I’ve read Inherent Vice several times, but I’m bound to miss at least a few things here.

If you haven’t seen it, correct that first:

Spoilers, needless to say, abound…but if you’re turning to a Pynchon story because you’re curious about “what happens,” you shouldn’t be turning to a Pynchon story.

We open with a shot of what seems to be (but isn’t necessarily) our protagonist’s house. His name is Doc Sportello, but we’ll get to him in a bit. For now, it’s a few seconds of lovely scene setting, and it’s impossible for me to look at this without dreaming of a Vineland adaptation. This is exactly how I’d picture the neglected, dormant beauty of Gordita Beach from that novel. Of course, there’s some overlap in characters and other details (including Gordita Beach itself) between Inherent Vice and that book, so maybe the comparison is unavoidable.

The narration, it sounds like, comes from Shasta Fay Hepworth, who we’ll see momentarily. She’s an ex of Doc’s, a private eye, and the novel opens with her coming unexpectedly to his home to discuss some impending sour entanglements with her more recent flame, the billionaire land developer Mickey Wolfmann. Specifically, the possibility that his wife is going to have him committed…and that she might want to be involved.

I’m having trouble deciding if this is narration recorded specifically for the trailer or not. I’m leaning toward no. And while it all rings a bit false to me — I’m not a big fan of films or television spelling out the reasons you should find them absurd — the fact is that Inherent Vice, though it’s by a wide margin the least complicated of Pynchon’s novels, is still pretty damned complicated.

That in itself wouldn’t be a problem if director Paul Thomas Anderson wasn’t interested in adapting it faithfully…but as we’ll see shortly, he absolutely seems to be. (At least overall.)

For that reason…yeah. Having a character catch the audience up with what the fuck is happening is probably not a bad idea.

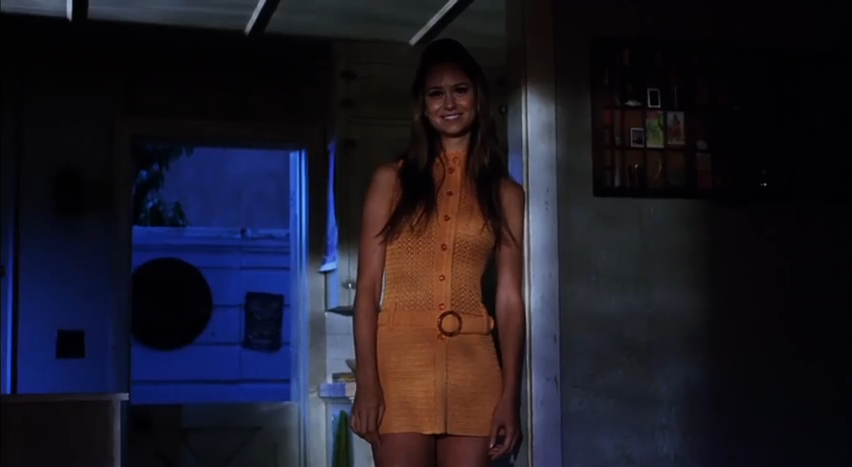

Shasta is played by Katherine Waterston, with whom I am not familiar. But I have to say that she looks the part. She’s very believable as the kind of girl you stay in love with long after you should know better.

We see her later in the trailer, too, presumably in flashback, and though our glimpses of her aren’t long enough to sell the difference yet, if you keep your eyes open you can absolutely see the distance between the girl he fell for and the woman standing in his apartment, “looking just like she swore she’d never look.”

With Doc, her life was pot and trippy music. With Wolfmann — and others like him — it was obviously something else entirely.

Better? Worse? Doesn’t matter. Point is, it’s something Doc could never provide.

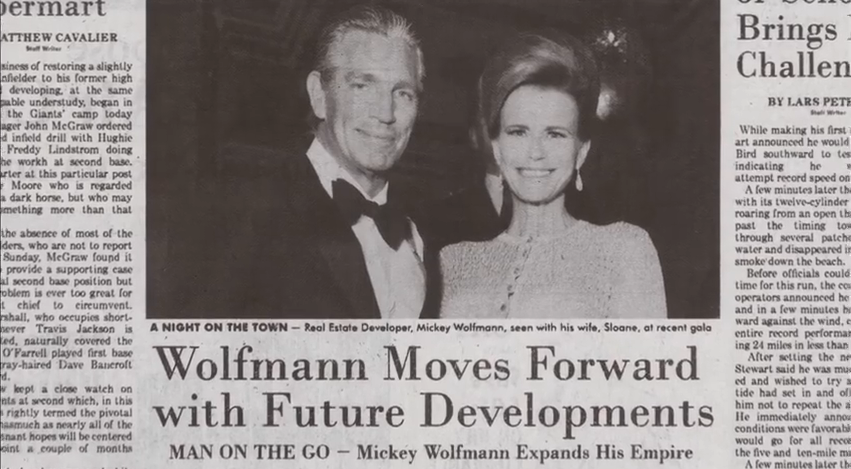

We don’t get much of a look at Mickey Wolfmann in the trailer, which is fitting, because Doc doesn’t get much of one at him in the book. Wolfmann is a presence more than a character, and that’s fine. It keeps his motives — and the motives of others, as they relate to him — at a distance.

Wolfmann in the book is much as he would be to us in real life: an image in the newspaper, a name overheard but not really understood. Doc encounters those who know him personally, but is always on the other side of that camera lens there. It remains to be seen if the film will keep him at a similar distance. I hope it does, because that was quite effective at building character through unexpected angles.

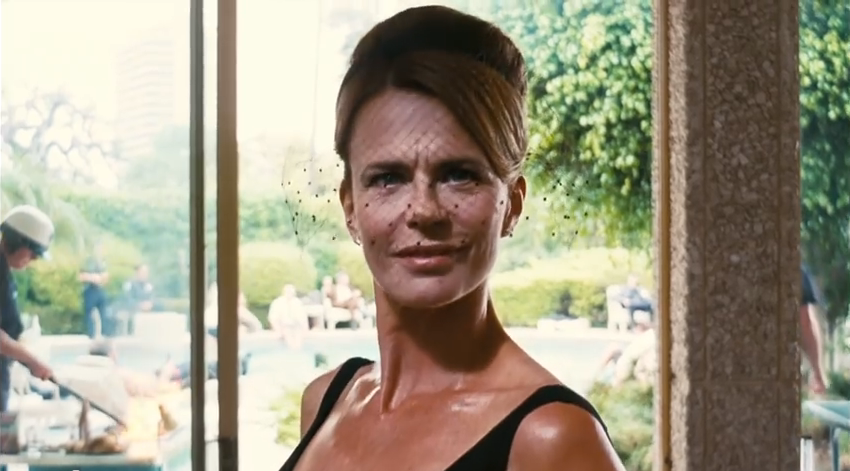

His wife, Sloane, is somebody Doc does get to know in person, and the ignorant vapidity of the character comes through very well both in this photograph, and when we see her in person momentarily.

See? I love that she’s wearing a veil of mourning along with a bathing suit and suntan lotion. It really goes to show how much she misses Mr. Wolfmann. A great detail in this scene — and the reason I capped it — is that you can see that the man barbecuing is wearing a policeman’s helmet, and it’s almost as easy to make out more uniforms in the background.

In the novel, Wolfmann’s palatial swimming pool was indeed taken over by the police officers sent to investigate his disappearance, and it’s suggested that they were enjoying this seized luxury before the feds showed up to take the case away from them.

Riggs Warbling, here. No idea who plays him, but he’s perfect for the character of Sloane’s “spiritual coach.” The narration refers to him as her boyfriend. That’s not entirely wrong, but there’s more to him as a character than that.

In fact, one of the great moments in the book occurs late in the story, when Doc finds him in one of the structures he talks about here: zomes. They make excellent meditation spaces, he says, and I’m hoping Warbling gets to see his arc through and isn’t just used as a visual punchline for this scene.

Either would be fine…but zomes, man.

Zomes.

Now this is interesting. The construction site photo plays a large role in the book, but here we can clearly see that the sign says they’re at the future site of the Kismet Hotel and Casino.

The Kismet is in the novel — with a connection to Wolfmann — but Doc at first isn’t able to make out the name on the photograph. Eventually he finds out it’s the Chryskylodon Institute…which is referenced in the narration here as a “loony bin.”

So this may mark our first significant deviation from the plot of the novel. Instead of the Wolfmanns laying out the funds for Chryskylodon as they do in the book, they lay them out for the Kismet. Yet Chryskylodon (under that name or another) still plays a role in the film, as we see it shortly with the STRAIGHT IS HIP motto above its door.

We also see Coy Harlingen there…but we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

In the book, the photograph also sees Sloane pretending to operate a piece of construction equipment. Here, for logistical reasons certainly, she’s standing with the traditional novelty scissors instead. That’s not nearly as significant as the Chryskylodon / Kismet switch, which interests me to no end.

Doc driving through Channel View Estates, a venture Mickey Wolfmann was heading up when he disappeared. There’s a temporary strip mall in the distance, which houses Chick Planet Massage. We’ll see that later in the trailer, too.

The bikers fleeing the scene does indeed happen soon after Doc’s arrival in the book, but here it happens during his arrival. Not as noticeable a change as the Chryskylodon / Kismet thing above, but considering the fact that this is when Wolfmann goes missing — and a homicide takes place taboot — the difference in timing could be significant.

The Chryskylodon Institute in Ojai. At least, I think it is. Judging by the robes and its strategic placement in the trailer as Shasta says “loony bin,” it at least fills the role Chryskylodon filled in the book.

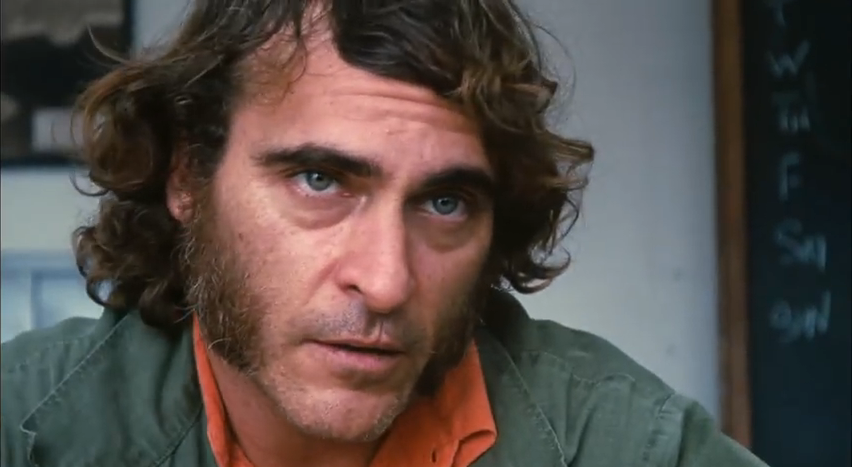

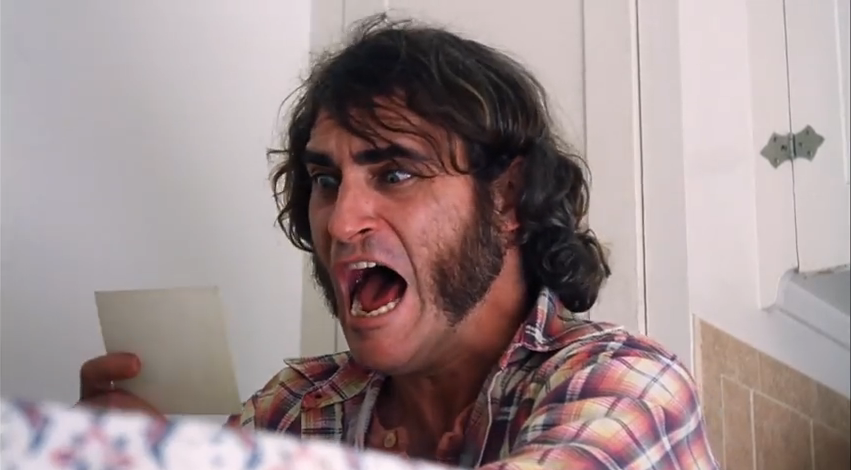

And now we’ll talk about Doc…played here by Joaquin Phoenix.

I wasn’t entirely enamored with the casting of Phoenix…but that’s less to do with him than it is with my disappointment that the rumored casting of Robert Downey Jr. didn’t pan out. Now that would have been a stellar Doc.

Phoenix, though, seems like he’s going to be a great fit, and this little moment with him walking toward the police station — and being carelessly shoved over by the cops — says a lot about who he is, as well as one of the central dynamics in the film.

Doc’s a private eye, but whatever talent he has for his profession is easily overlooked by those who see only his schlubby, unprofessional demeanor. It says a lot that on his way to speak with the police, Doc would dress exactly this way. He’s not a jerk…he’s just a man out of time.

It’s a great little detail that he’s wearing huaraches, too. I wonder if he’ll lose one like he does toward the end of the book.

His shoddy treatment at the hands of the law — sometimes deliberate, sometimes not, sometimes calculated, sometimes just for fun — informs my favorite relationship in the book. And, come to think of it, my second favorite as well. This shove, and that fall, bring it all perfectly home.

Of course, the cops get shoved around themselves by the feds, which may or may not translate to the film, but it certainly is starting to seem like it might.

A nice, good look at our hero. I don’t have much to say here, but I thought it only fair to spotlight poor Doc, as so much in the trailer eclipses him.

Of course, that’s thematically resonant with the book, so…no real complaints.

Phoenix doesn’t look or act much like what I got from Doc while reading, but I’m actually glad for that. It means this interpretation will be a lot less likely to “overwrite” my inner memories.

Josh Brolin plays Bigfoot Bjornsen, Doc’s professional antagonist on the badge-wearing side of things. When Brolin’s casting was announced, a friend of mine gushed about how perfect he was for the role. I didn’t have the same reaction. I’d pictured somebody more along the lines of John Goodman. A younger, meaner John Goodman…but not Brolin.

Seeing him here, though? It really is perfect. He plays the consciously square-jawed detective (police detective, that is…) very well, and we even get a glimpse later in the trailer of how well he might play the less self-assured iteration of the character.

Bjornsen’s relationship with Doc is my favorite in Inherent Vice. It seems like a more profound development of the Zoyd / Hector relationship in Vineland, with mutual hatred managing to coexist with sincere mutual respect. These are two characters who despise so much about each other, and yet they each recognize in each other a longing for a world that doesn’t exist anymore. Maybe never did.

A different world for each of them, certainly, but they’re exiles all the same.

Now this was casting I did flips over. Still am, actually. Benecio del Toro plays Sauncho Smilax, Doc’s attorney. We don’t get much of him in this trailer, but his look is perfect. I couldn’t be happier about del Toro handling this character.

This moment seems to come from the lunch he has with Doc at The Belaying Pin, and I’m sure that drink in the foreground is his Tequila Zombie. This is also, if I’m correct, the scene in which he introduces Doc to the Golden Fang, a ship — or something — that factors in a major way into the events unfolding around Doc.

The clips here also demonstrate that the characters haven’t quite settled on where the emphasis lies in Mickey Wolfmann’s last name. It’s that “man” part that’s causing so much trouble…some pronouncing it like it’s pronounced in “Silverman,” and others like it’s pronounced in “Super Man.”

Some pronounce it as you would the name of a wealthy land developer, and others as you would a super hero.

And I like that. One hell of a lot.

A relatively minor moment early in the novel, and something I didn’t expect to make it to film, is Doc tying strips of an old t-shirt into his hair to build up an afro overnight. The movie could have opened with his hair that way, and I find it interesting that they bothered to include this…along with other seemingly minor details.

At the same time, much seems to be left out. Doc’s friend Denis, for instance, doesn’t seem to have a role in the film. And while not every character in the book could be expected to appear on screen, Denis serves two major purposes in the novel. The most obvious is probably the fact that he has a hand in the way it all ends. But in general he serves as comic relief throughout the book.

In the former sense, I have to assume the ending — or at least the way it plays out — has been changed for the film. In the latter…well, look at the trailer. The entire thing is comic relief. Denis might play on the page as some welcome silliness, but Pynchon’s writing is all silliness when translated to the visual.

Or, again, so it seems.

Doc is on the phone with his Aunt Reet, a real estate agent who gives him the lowdown on some of Wolfmann’s business dealings. The “wants to be a Nazi” bit is an actual line of dialogue from the book, and I have to admit it’s extremely strange to me to hear these lines spoken out loud.

Not that they sound bad out loud, but the more you read Pynchon the more you get accustomed to a kind of internal rhythm of dialogue. When that dialogue is brought into our world, spoken with our rhythms, it’s a little chilling. Like waking up next to a krees you found in a dream.

But, yes. With lines like this necessitating delivery like this, Denis might not have stood out as comic relief at all.

We then see a brief shot of Doc speaking with Jade (possibly Bambi…it’s been a while since I’ve read Inherent Vice) from Chick Planet Massage. Not much to say about it, but if you’re wondering: that’s who it is.

Jena Malone plays Hope Harlingen, who hires Doc to look into the whereabouts of her husband, Coy. She believes he might still be alive, even though the official story is that he died of a heroin overdose.

All of Doc’s cases in Inherent Vice are interrelated, but it’s still easy to segment them out, at the very least by who hired him. The Harlingen case leads to many of my favorite moments in the book, and it’s second only to the disappearance of Mickey Wolfmann in terms of overall importance. That’s why I’m a little sad to see it play out like this:

See? We don’t need comic relief in a movie that takes one of the book’s most affecting scenes and makes a joke out of it. The movie is comic relief.

It’s a funny moment, I admit, but Doc mindlessly screaming, I’m sure, won’t stack up to the emotional relief of the scene in the book. See, Hope, Coy, and their infant daughter Amethyst were all wracked by the horrors of heroin. Hope and Coy directly, little Amethyst by proxy. The story she tells Doc about it is harrowing…and in a moment of small, uncommon cosmic mercy for Doc, he sees Amethyst wander into the room, and she’s fine. She’s healthy. She made it out.

It’s a great scene of tension and release, so it’s a little disappointing that it gets played for laughs here. Not worrying, mind you, but disappointing.

…aaaand suddenly I’m not disappointed anymore. Reese Witherspoon looks like a fantastic Penny, the Deputy DA who now and then holds Doc’s heart, and some other things. The awkward exchange here involves her over-protective cubicle mate Rhus, and it’s played with perfect, absurd tension.

In the book, Penny is an attractive, intelligent, uptight foil to Doc’s…well, to Doc’s opposite of all that. Witherspoon absolutely looks the part, and somehow, in a way I can’t quite articulate, fits the mold of the kind of girl who would fall for Doc against every ounce of her better, more reliable judgment.

Of course, Penny’s not entirely trustworthy herself, being as she shops poor Doc to the feds right about…

…now.

Agents Flatweed and Borderline, investigating the disappearance of Mickey Wolfmann, shoving the local badges and batons out of the way in order to do so. At least, ostensibly. The book paints a portrait of a vicious cycle, reinforced by the sheer power of an official pecking order.

I’ll be purposefully vague here. At the bottom (arguably) is Mickey Wolfmann, who could use some assistance. Doc is just above him, willing to provide that assistance. Above Doc is Bigfoot (and his colleagues) who shut Doc down so that they can handle the situation their way. Above them lurk the feds, who shut the cops down so that they can keep Wolfmann away from the help he needs.

It’s a peek into the inescapable future that Vineland has already shown us…but Doc’s there, hovering on the brink of a new decade, and that’s why moments like the reveal that li’l Amethyst is a-ok are so important.

Doc knows he’s a lost cause. He knows there’s no place for him in the years to come. But seeing some assurance, however small, however trivial, that somebody, somewhere, might come out of this okay…why, that’s all he can ever really hope for, isn’t it?

That’s why I wish it wasn’t a punchline.

Because it isn’t funny.

It’s all the guy’s got.

Owen Wilson is a great choice for Coy Harlingen, the not-exactly-deceased ex-heroin addict, saxophonist, and political turncoat. He has exactly that sort of effortless attractiveness that also feels quietly haunted. And, hey, he’s a pretty great actor in films directed by guys named Anderson.

Doc finds him here renting a large house with The Boards, a band of the undead themselves. One very nice detail is the saxophone on the ledge in the background…Coy’s icon, and what helps Doc to locate him in the first place.

I’m very much looking forward to seeing the Harlingen saga play out on screen. There’s the potential there for a lot of heart, and unlike the scene earlier, it looks like the emotional holds steady in the Board mansion.

Also, compare the dark, morose environment in which Coy is lost with the bright, airy home Hope still occupies. That’s not unique to the film, but that’s a wonderful visual suggestiveness.

A quick flash of Doc in front of Mickey Wolfmann’s tie collection. He’s with Luz, the Wolfmann housekeeper, and they’re about to do what you think they’re about to do.

Doc looks different here because he’s in the Wolfmann residence under false pretenses, looking like he swore he’d never look. Natch.

In the book, the ties are custom painted with very lifelike erotic art, each featuring a different woman Mickey Wolfmann has slept with. It doesn’t look like that’s the case here, but perhaps the imagery is on the back.

Either way, the ties are crucial to Doc’s investigation. Out of his own foolish curiosity he tries to find one featuring Shasta, and fails. Later, in Chryskylodon, he finds that tie…notably not around the neck of Mickey Wolfmann.

The fact that they bother to set up this otherwise irrelevant scene suggests that this detail will still factor into Doc’s investigation. Further confusing the change from Chryskylodon to Kismet in the ground-breaking ceremony.

We get a very short glance of Martin Short, out of retirement to play Dr. Rudy Blatnoyd…another in a long (long…) line of untrustable Pynchon doctors. He’s most likely with his dependent patient (and daughter of one of Doc’s old clients) Japonica Fenway, but I don’t know for sure how much of his “Smile Maintenance” we’ll see in the film.

Blatnoyd was a small role in the novel that petered out before it began (with good reason, however), so I’m very shocked Short took it. Either it’s been expanded upon here — which I for some reason doubt — or he was a fan of the book himself.

Whatever the reason, he’s a hell of a get, and I couldn’t be happier with most of these casting choices.

Interesting are the bits of set dressing behind him. An oriental dragon on the coffee table and a ship on the wall…both of which are gold, and both of which passively represent the Golden Fang. Indeed, in the book, Blatnoyd’s very building resembled a big golden incisor.

What is / was / will be the Golden Fang? I’ve read Inherent Vice more times than I could tell you, but like The Maltese Falcon, and, shit, that ol’ muted post-horn even, that’s not what matters. What matters is what it does to the people who seek to find out.

I wonder if the film will retain that mystery. Something I saw in a cast list worries me that it will not.

We then flash through scenes of Sauncho picking up Doc from the police station, the younger, original Shasta Fay Hepworth, and Luz overtly seducing Doc (and me…) in front of Sloane Wolfmann.

After that, we get to a very notable image: this Last Supper homage, featuring various members — past and present — of The Boards, having a “heated discussion over a number of pizzas.”

Coy is visible here, and in the book it’s an important clue to his whereabouts. However, in the book it’s a still photograph that Doc is consulting. Here it’s in motion, which means either Doc is present for the scene, or it’s a flashback.

Regardless, an interesting change. This is possibly so that Doc’s photographer friend Spike could be cut out of the storyline without sacrificing an easy visual punch.

I love that this scene plays for so long in the trailer. Bigfoot ordering more pancakes (with lingonberries, I hope…) is one of those comic moments that definitely plays better on screen than it does in the book, where it just feels like an amusing incongruity.

Doc’s faltering embarrassment is fantastic, and the comedy is no doubt going to cushion the hard fact Doc learns here: the Mickey Wolfmann investigation is leading him closer and closer to one Adrian Prussia.

Who’s that? The trailer doesn’t answer that question…or, indeed, even raise it. But we’ll discuss it shortly.

We’ve now heard Brolin do his smug, intimidating Bigfoot, and his silly, comical Bigfoot. We don’t really get to hear the fragile Bigfoot, but if the film plays out like the book did, there will be plenty of time for that later.

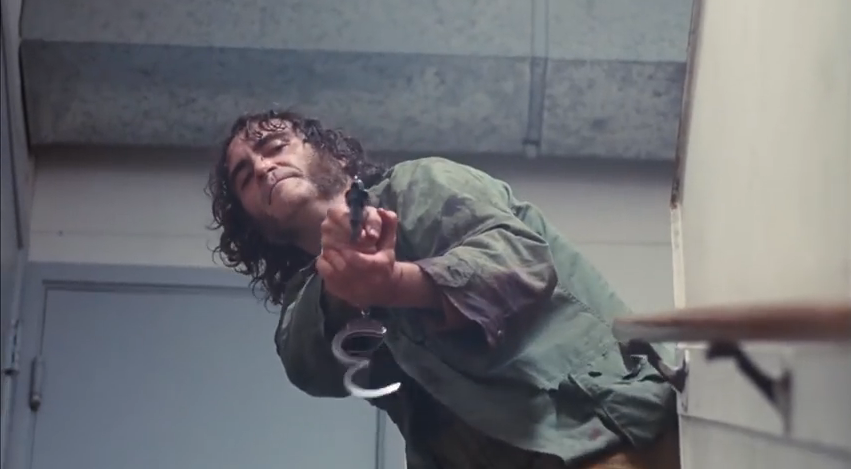

With the exception of a couple of midpoint scenes (such as Bigfoot with his pancakes above), this trailer sticks, understandably, to the front part of the film. Here, however, we get a look at one of the very last plot points.

The dangling handcuffs, the gun, and the “Did I get you?” line all make it clear that the body he’s stepping over belongs to Puck Beaverton. Beaverton doesn’t factor into the trailer otherwise, and neither does his partner Einar, nor his fiancee Trillium.

Theirs was an interesting subplot — and part of the reason Doc went to Vegas (home of the Kismet) at all — so we’ll see. It’s possible that “Puck” here is actually just an anonymous heavy for Adrian Prussia as far as the film is concerned, but I hope not. I really want to hear him sing some Merman.

Doc is asking Prussia, during a brilliantly unprofessional shootout, if he hit him. I’ll spare you the answer, since doing so wouldn’t help identify anything happening in the trailer and would just be a spoiler for spoilers’ sake.

I will say, though, that it’s interesting to me that Prussia is kept out of sight here…just as he is for so much of the book. (And, indeed, in this very gunfight.)

Prussia is Inherent Vice‘s bad guy. At least, within reason. Like Ned Pointsman in Gravity’s Rainbow and Brock Vond in Vineland, we know there are infinite levels above, all working the controls behind the scenes. But as far as what Doc gets to see goes, Prussia’s the one motherfucker he doesn’t want to tango with.

So, yeah. Inevitably, it comes to this. And I can’t wait.

Doc outside of Chick Planet — and not at all willingly — with Bigfoot. The trailer ends with a scene of Doc getting knocked out in the massage parlor, and when he wakes up, this is where he finds himself. He gets taken in for questioning, and that’s when Sauncho (as we’ve seen above) comes to get him.

Questioned about what? Well, the homicide. That unfortunate body on the stretcher is Glen Charlock’s, and it’s this murder that sets the gears of complexity really turning. It all interlocks. The only question is…how?

This is when the motorcycles flee the scene. The deed is done on poor Glen, who was working as one of Mickey Wolfmann’s bodyguards, and the bikers hit the road…which Doc hears right before he gets whacked on the head. In the trailer, however, he’s driving to the scene as the bikers leave, which significantly alters the course of events, and doesn’t actually put Doc at the scene of the crime.

It could be nothing, but I’ll be curious how much deviation from the book a change like that will trigger.

The LOVE caption is stylized to resemble the cover of the Inherent Vice novel, as are all of the captions in the trailer. This one I’ve singled out, because it’s from another moment I didn’t expect to be adapted: a flashback of a younger Doc and Shasta, caught in a torrential rain as they seek out an address given to them by a Ouija board.

Considering the fact that they asked the board where they could score good weed and the fact that the address ends up connected to the Golden Fang, this is a scene of sweet, unexpected warmth.

It’s no wonder Doc clings to it as control spirals away from him…and it’s a pleasant surprise to find that it made the cut in the film.

God knows the poor guy needs all the happiness he can find.

Fragile Bigfoot after dark. His unfortunate homelife is played for both laughs and pathos in the book, and though we can’t hear anything, seeing him cow to his wife while talking on the phone to Doc — his chosen nemesis — is heartbreaking.

Another great, unnecessary element of the book that I couldn’t be happier made it to the screen.

Doc and his client Tariq, framed in perfect awkwardness here, in what’s clearly their first meeting. Tariq knew Glen Charlock…and, in fact, has a fling with Glen’s widow once the body gets cold.

Michael K. Williams serves Doc some brilliant, well-deserved bafflement. Their consultation is one of the novel’s funniest scenes, and I wouldn’t be surprised if I end up saying the same for the film.

And, finally, we end where things begin: Doc comes to Channel View Estates to track down Mickey Wolfmann, and gets knocked unconscious in the massage parlor. While he’s out, Wolfmann gets kidnapped, his bodyguard Glen Charlock gets killed, and Doc wakes up way over his head.

Maybe, as Shasta herself opened the trailer by suggesting, Doc should have just looked the other way.

Fact is, though, it’s happening.

And it’s happening in December.

I’ll see you there.