As in the case of the Reader Mail feature from Monday, Compare & Contrast is something I’d like to do periodically on this blog, and I have a good number of things I’d like to eventually write about in this fashion. But now, since it’s Wes Anderson month, and since my girlfriend and I just rewatched Bottle Rocket, I thought this might be a great time to introduce it.

After all, for the first time, I think I’ve figured out just why that film’s handling of the central romantic relationship rubs me the wrong way. It also made me think about a pretty similar corollary in The Darjeeling Limited, which I think handles the same material far more impressively, and retroactively sheds some light on what Bottle Rocket did wrong.

The Situation

In both cases a well-enough-off American man seduces a young woman of differing cultural heritage. In both cases the men are guests at their places of employment, and the women are employed to keep them comfortable.

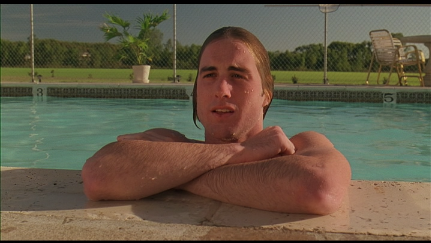

In Bottle Rocket, the American man is Anthony Adams, played by Luke Wilson. Anthony is staying at a motel with two of his friends when he first sets eyes on the woman, a housekeeper named Inez.

He doesn’t speak to her, but he follows her with his eyes, and his facial expression (alongside the tellingly infatuated camera work) makes clear that he feels something for her. On the surface however, there’s no real way to separate whatever he thinks he feels from simple lust.

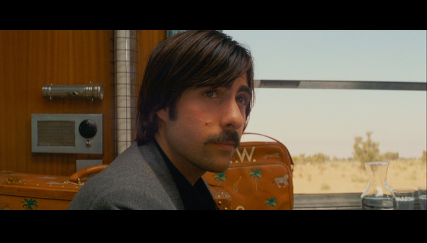

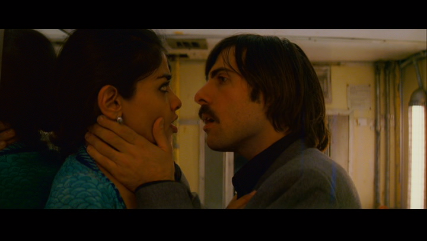

In The Darjeeling Limited, the American man is Jack Whitman, played by Jason Schwartzman. Jack is traveling by train with his two brothers when he first sets eyes on the woman, a stewardess named Rita.

Rita appears with snacks and drinks for the brothers, and, as such, Jack does engage her directly as part of their first meeting. Compared to Anthony, he is taking an active role, and not simply staring at her from afar (it also helps that Rita is aware of both his presence, and his gaze).

Rita, in contrast to Inez, is a known quantity. Jack knows at least something about her, which makes his feelings — more on what feelings those are in a moment — more understandable than those of Anthony, who doesn’t even know what Inez sounds like…he can only know that he likes the way she looks.

Jack also much more openly has hunger in his eyes. Rita offers him savory snacks and sweet lime, but it’s an unspoken third option that he seizes immediately upon. Jack, in a word, is predatory. So is Anthony. The major difference here, however, is that The Darjeeling Limited is aware of the decidedly un-savory nature of Jack’s motives, while Bottle Rocket remains naive. As a result, it’s Bottle Rocket that fails to handle the situation maturely…something that ties at least somewhat into Anthony’s character, but also would have benefited greatly from some larger, film-wide acknowledgment that we’re not supposed to agree with his actions.

The Courtship

Instead, we have the romance playing out successfully, which indicates that Anderson didn’t quite understand how problematic the situation actually is. Anthony essentially stalks Inez, and his overtures to her don’t sound as innocent as he certainly thinks they do. In fact, they belie a predatory mentality that Anthony wouldn’t recognize in himself, in spite of the fact that he goes about trailing Inez, forcing himself into her routine and even ignoring her instructions not to follow her into a guest’s room. Anthony is essentially courting Inez in such a way that in reality would have had the police — or at least a motel security guard — called on him.

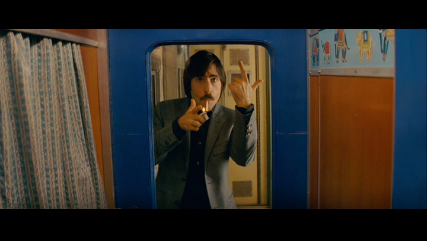

In Jack’s case, he is more aware of the lustful nature of his attraction, and even proclaims to his brothers his intentions to sleep with her. Jack Whitman is under no delusions about what he wants, and he makes no secret of it. His courtship of Rita is as accelerated and urgent as Anthony’s, but whereas Anthony believed he was in love and followed Inez around to prove it, Jack just wanted to fuck, and beckoned to Rita to follow him down.

So far, so fair. After all, different characters might feel different things, and they should certainly be going about achieving their goals in different ways. But there’s one thing we haven’t discussed yet, and it’s a big one: the language barrier.

This is where the major difference comes to light: Inez does not speak English. Or, at least, not very well. She doesn’t understand most of what Anthony is saying to her, and while that’s certainly a humorous situation as he knowingly engages her in conversation anyway, it leads to a somewhat unsettling feeling when the topics turn more serious, and we have no reason to believe that Inez understands what they’re even discussing, at least not without an interpreter. One is fortunately on hand in the form of a dishwasher named Rocky, but he is notably not present for most of Anthony and Inez’s conversations.

The advantage here is firmly on Anthony’s side. He is the one with the money, and Inez is there to help. They’re both sharing the same space, but if Inez upsets him — or any guest — she is liable to lose her job, and be replaced rather easily. Anthony has no such fears or cause for concern. It’s notable that Anthony is even more ignorant of Spanish than Inez is of English, but that need not trouble him, as she barely says anything to him in return.

This should speak pretty loudly to Anthony — and to Anderson — that Inez is not interested at best, and fearful and intimidated at worst. At one point in the film Anthony takes a small picture from Inez and, assuming it’s her, asks to keep it. It’s actually a picture of her sister that she keeps in a locket that she wears at all times. Anthony asks if he can have it anyway, and she agrees…though there’s really no reason for us to assume that she understands the question. This American man who has followed her around all day and interfered with her job has now taken from her an item of immense sentimental value. At this early stage in his directorial career, Anderson doesn’t see that that might be illustrating something other than love.

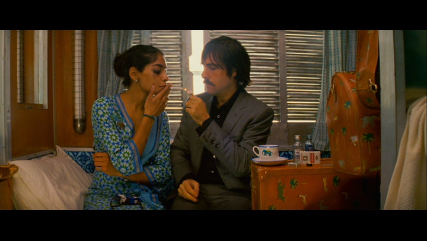

Jack, on the other hand, has no such difficulty communicating with Rita. She speaks his language, and his lack of interest in hers is a theme that The Darjeeling Limited explores in many ways across all brothers. It’s not shrugged off as Bottle Rocket allows Anthony’s to be; it’s a symptom of who Jack Whitman is, and the film doesn’t endorse his viewpoint.

When Jack engages with Rita, he does so as one adult human being to another. He is fully aware of her station in his life — and in life in general — and it’s clear that he does not consider her to be his equal (another theme explored by the film later on). He will say nice things to her and treat her well in an attempt to win her physical favors…but beyond that, there is nothing. He pretends that there is not a clear imbalance of power in their dynamic, but you can be certain he hasn’t forgotten it.

Jack’s courtship of Rita is no more or less hollow than Anthony’s of Inez. They’re exactly the same in terms of what they want — if not what they think they want — and they’re executed in similarly despicable ways. The difference is that Jack is aware of his inherent womanizing, and simply dresses it up in a nice suit when it goes out to play. Anthony is not aware of what he’s doing, and, as we’ll see in a moment, neither is Anderson.

Sealing the Deal

In each case, the elaborate seduction plot is a success. Both Anthony and Jack bed their respective sirens of the service industry, but the difference is that in Jack’s case, it makes some sort of logical sense; Rita behaves in some understandable, identifiable way. In Anthony’s case, Inez falls for him because the script requires her to do so, and what we see next is less an organic unfolding of a new relationship than it is a forced plot point without any clear connection to what we’ve seen before.

Early on, Inez is reluctant even to share the same physical space with Anthony. She’s rightfully concerned about this strange man who keeps plying her with words she can’t understand and refusing to leave her alone. She is uneasy and nervous around him, and all of that is perfectly fitting for the situation at hand. I would never argue that a capable artist can’t turn this, eventually, into a sort of complicated romance, but first the artist would need to be aware of how incompatible it is with such a traditional outcome. Instead, Anderson has Inez fall for Anthony as well, simply because she has to, in the small space of time it takes his friend Dignan to get a haircut.

She still can’t speak his language and it was only a matter of hours prior that his relentless hounding was both terrifying and unwelcome to her, but now she embraces him and kisses him in the swimming pool, because it makes for an admittedly nice image and that’s what the script told her to do. In an unintentional bit of artistic racism, Inez’s character doesn’t actually get to be portrayed like a human being with thoughts and feelings of her own.

By contrast, Rita in The Darjeeling Limited does not undergo the immediate magic of a script that needs a love scene. She does succumb to Jack, but she does so in a way that suggests that this is nothing new. Rich Americans come through here all the time, and this is just one way of coping with the endless stream. In fact, her physical engagement with Jack may well be as much a game for her as it is for him, and though he does selfishly interfere as she’s trying to do her job, as did Anthony, Rita is able to stand her ground and tell him to back off. That Jack doesn’t oblige shows us two things: that he knows what he’s doing, and that Anderson knows what he’s doing.

Rita, likewise, is not romanticized by camera angles and soft focus. Jack catches her in unflattering situations, such as when she’s smoking a cigarette through an open window. Rita is treated like a human being by the film, rather than as some heavenly agent of wish-fulfillment that doesn’t need a personality of its own. She can stand up to Jack, she can stand up to her boyfriend, and she can make her own decisions. Eventually she even has the strength to call Jack on his bullshit. That one of her decisions is to sleep with him anyway may well reflect poorly on her, but it at least does not reflect inhumanly on her.

The actual sex scenes as well as also ripe for comparison. In the case of Bottle Rocket, Anthony trots romantically around in search of Inez, whom he finds cleaning a vacant room, because she’s a minority and that’s what they do when they’re not washing dishes. She obligingly lays down and undresses, the strains of “Alone Again Or” by Love fills the air, and the two unlikely (and unrealistic) love birds smile like children and enjoy each other beneath an artfully fluttering sheet. In short, it’s exactly what Max Fischer imagined a night with Miss Cross would be like in Rushmore…before she dashed his naive and idealized view of sex. As lovely as this scene is out of context, it doesn’t fit into the actual flow or characterization of anything we’ve seen before, and, as such, it just makes it seem as though Anderson still had some growing up to do.

He’s certainly grown up by the time of The Darjeeling Limited, as Jack’s sex with Rita is raw, impersonal, and not romanticized in the slightest. The two don’t even bother to disrobe, the only soundtrack is the train rattling noisily around them, and any possibility of romance is dashed by Jack’s abrupt digital penetration and Rita’s instructions not to cum inside of her.

It’s not romantic, and it’s certainly not sexy. But Jack and Rita don’t want romance, and they don’t care if they’re sexy. They want to have sex, and they have neither the time nor interest to make it anything more meaningful. When Anthony beds Inez, the movie presents it to us as a grand, triumphant moment for both of them. When Jack takes Rita against the wall of a moving train, the movie presents it to us as something that happened. And that’s okay, because when two strangers have sex, that’s all that it is.

That might sound like a kind of cheap way to put it, but not if you’ve ever fucked before it isn’t.

The Resonance

In other words, the big difference between these two films is that The Darjeeling Limited is aware of what’s happening, and presents it realistically. Bottle Rocket is not at all aware of what’s happening, and so is able to present it in a much more romanticized light. The latter sounds appealing, but it serves as a barricade for the audience. The former they can believe in, but the latter seems to exist somewhere without them, separate — and notably so — from how they could have reasonably expected these events to transpire.

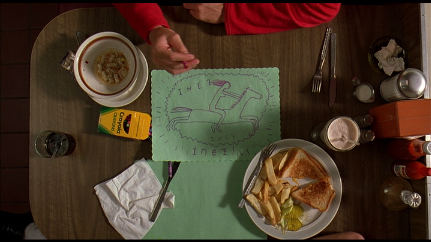

This is clear as well from contrasting the ways these men express their feelings to others. In Anthony’s case, he picks up a crayon and doodles Inez — tellingly without eyes or a mouth but with pronounced mammaries — riding a horse. The horse has nothing to do with Inez, or with any of her interests, or with anything he could possibly know about her. In fact, the only word he scrawls alongside the picture, three times, is her name…again, one of the very, very few things he knows about her, which should really remind the audience how shallow this “love” must be, in spite of everything the film wants to tell us to the contrary.

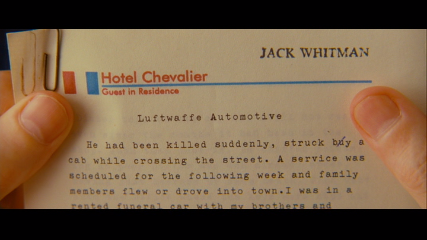

In Jack’s case, he expresses himself through the clearly more mature method of writing fiction. (I’m not trying to put my own literary tendencies on a pedestal here…I just think it’s safe to say that writing fiction is more or less universally understood to suggest more maturity than drawing on the backs of placemats with crayons.)

We don’t know that he will write about Rita, but we do know that he wrote about his experiences at the Hotel Chevalier and at Luftwaffe Automotive…two other scenes in the film that Jack could only process by writing about them. In fact, Jack may well not write about Rita. Why would he? She is one of many woman he will sleep with, and it’s possible that he won’t even remember her name.

Jack has a method of dealing with things — or, perhaps, a method of avoiding having to deal with them — and it’s up to him whether or not Rita should ever factor into that. She might not…she means nothing to him, and he always knew that. So did the film.

Anthony labors under the misapprehension that Inez means more to him than she really could, and so he picks up a crayon and gets to work. We do see Anthony doodle once more in the film — a nice flipbook animation of Dignan pole-vaulting during their upcoming heist — but it’s more a way of passing the time than it is any serious and mature exploration of the feelings and concerns racing around inside of him. Point: Whitman.

The Aftermath

For Anthony, he and Inez get to live happily ever after, at least as far as the film is concerned. We leave Dignan in prison, Bob Mapplethorpe is getting along with his brother, and Anthony is happy with Inez, who plans to send Dignan a care package. Everything’s worked out just fine for these two crazy kids who couldn’t understand a word each other said and had nothing in common or any reason to connect or to continue corresponding, let alone develop their relationship into anything larger than “housekeeper” and “that creepy guy who fucked the housekeeper.”

It feels unearned, not least because Inez doesn’t even get to show up in person at the end of the film and let us know — in some way — what she’s feeling. We see that it makes Anthony happy, and that’s enough. Or is supposed to be. In reality, it just feels disjointed. Inez recoiled from him, then slept with him, then said she loved him, and then apparently entered into a serious relationship with him, but we never get any insight into why, or into how she might be feeling. Does Rocky still come along on their dates to translate? Bottle Rocket frames the situation as a triumph of romance, but it just feels like a story we can’t understand…perhaps as though it’s being told in an unfamiliar language.

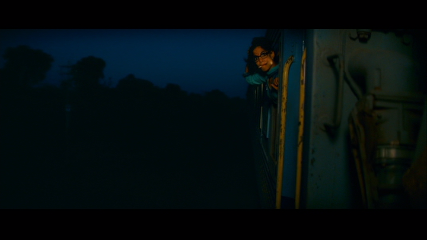

For Jack there is no aftermath, because he was always aware that there wasn’t a relationship in the first place. There was no love involved. They had sex. Jack would have liked to have had more. When the Whitmans are kicked off the train Rita leans out of a window to offer him savory snacks, and something very strange and unexpected happens: she cries.

Unlike in Bottle Rocket, where emotion was constantly abound whether or not it was needed, appropriate or earned, here emotion was never part of the arrangement. Rita cries for Jack, because she feels sorry for him. Jack, hoping it’s not as personal as it really is, assumes she must have accidentally gotten maced during the brotherly spat that got them ejected.

He remains distant, and cold. He’s more comfortable without the personality, without the investment, and without the emotion. He walks to keep pace with the train as it pulls away, as the strains of “Charu’s Theme” play behind him. There was no music during the sex and no real soundtrack to the seduction, but here, at last, is Jack’s artistic overture toward romance: the goodbye. For Jack, the romance is in the heartbreak. He may not feel compelled to make every sexual encounter one to remember, but he sure knows how to make an exit.

Wes Anderson, as noted above, would do much better with handling cross-barrier romances in the future, whether it’s teacher / student, adopted siblings, or the stunted courtship of Ned Plimpton and Jane Winslett-Richardson. He made one mistake early on, but after those awkward romantic fumblings, he sure grew up fast.

So does this constitute a “don’t watch Bottle Rocket” or a “don’t expect too much from the love story in Bottle Rocket while you watch it and enjoy all the other stuff going on”?

It’s…hard to say. Definitely the latter, I guess, but with the further qualification that you don’t watch this until you’ve seen at least two other Anderson films. (Any two…but I’d recommend The Royal Tenenbaums and either Moonrise Kingdom or Rushmore to start.) It’s worth seeing, if only for the brilliant climax, but I’d probably be hard pressed to call it a good movie even without the problematic love story.