Fiction into Film is a series devoted to page-to-screen adaptations. The process of translating prose to the visual medium is a tricky and only intermittently successful one, but even the fumbles provide a great platform for understanding stories, and why they affect us the way they do.

The line separating bravery from idiocy is finer than you might think.

The line separating bravery from idiocy is finer than you might think.

The same self-assurance that helps you triumph in the face of insurmountable odds is what causes you to beat your head repeatedly against a brick wall. The same refusal to succumb to tempting lies is what keeps you from accepting uncomfortable truths. The same unrelenting confidence can lead you to glory or damn us all.

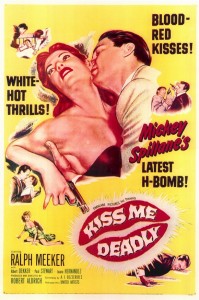

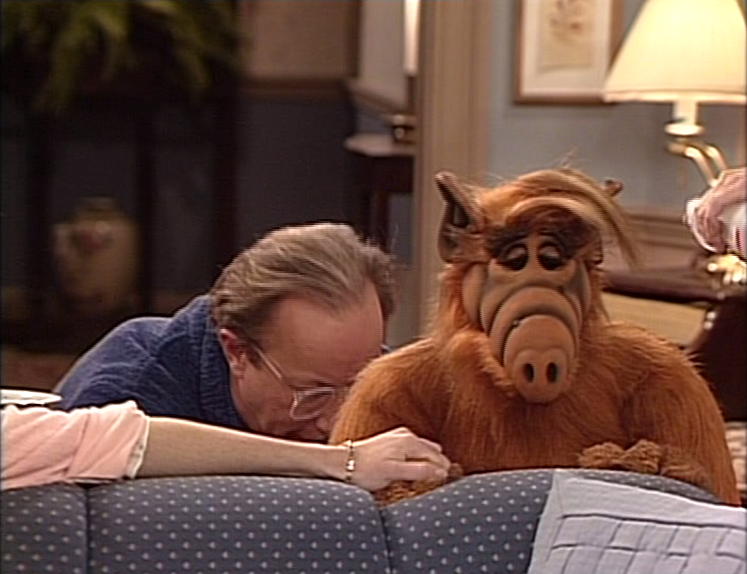

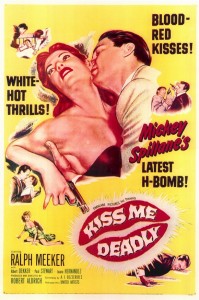

Kiss Me Deadly is Robert Aldrich’s noir masterpiece, and one that ensured we’d never be able to see the genre the same way again. It was — and is — a knowing study of itself…a loving condemnation of hardboiled detective fiction, while also managing to be one of the screen’s best examples. What’s more, its success hinges entirely upon its willingness to second guess its source material.

I love noir. I can’t make that clear enough. The Maltese Falcon, Double Indemnity, The Thin Man, The Postman Always Rings Twice, The Long Goodbye…when I brainstormed a list of titles to cover for Fiction into Film, those and many more rushed to the top. In fact, I could base an entire series around noir adaptations only, and while nobody in their right mind would read it, I’d have a hell of a fun time keeping it pointlessly alive. So I consider it something of a personal triumph that I waited a whole four installments to get around to covering one. And now that I am, there’s no more fitting emissary than the brutal, desolate, devastating Kiss Me Deadly.

Based on the book of a similar name (Kiss Me, Deadly, with a comma) by Mickey Spillane, the film follows private investigator Mike Hammer through a conspiracy that centers around a dead woman…and what she did or didn’t know. Hammer is warned off the case by the police, but he follows what little of the trail he can anyway, in the hopes of unraveling the mystery and finding a big pay day at the end.

As his secretary in the film puts it, “First you find a little thread. The little thread leads you to a string. And the string leads you to a rope. And from the rope you hang by the neck.” It’s a metaphor Hammer adopts himself — intentionally or not — when he explains his motives to another character…conveniently leaving out that last bit.

In print, Mike Hammer was a grizzled, world-weary detective in the tradition of Philip Marlowe and Sam Spade. But Aldrich saw something in Hammer that he didn’t see in those other, spiritual colleagues of his: he saw that Hammer was a jackass.

The film, as a result, is a passive deconstruction of what was (at the time) an immensely popular character. It was a daring move…one that earned Aldrich the scorn of Spillane and his fans, but one which also ensured that the film would outlive the character. While Hammer might have fallen from the cultural consciousness, characters like him have not, and Kiss Me Deadly is just as damning a condemnation of Hammer’s type as it is of Hammer himself.

Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly toys from its first scene to its last with a single idea: what if this central detective figure is dead wrong? What if the man we’re trusting to sort things out for us is actually making them worse? What if this character who is meant to be one step ahead is always, unknowingly, several steps behind?

The exploration of this theme is by turns hilarious and horrifying. From the page Hammer retains all of his swagger, his wit, his brash charisma, his sexuality, and his willingness to work behind the back of the law. But the film robs him of the one essential thing that all hardboiled detectives secretly need: the authorial promise that he’s right.

As a result we get a detective film that plays entirely by the rules of the genre, and still manages to deliver us into a hopeless and inescapable climax; a nuclear nightmare in which the cool confidence of the main character has doomed us all to a slow and torturous death. It’s like a version of The Maltese Falcon that ends with Sam Spade going door to door gunning families down in search of the real thing.

It’s tempting to see this adaptation as a mean-spirited jab at Spillane’s talent, but I don’t believe it is. In fact, the first time I read Kiss Me, Deadly I was surprised by how effective the writing was. It wasn’t great, and certainly wasn’t the kind of thing I’d recommend to anyone who wasn’t in desperate need of detective fiction, but Spillane was good at what he did.

He wanted to create a cruel world of crime and violence, with one manly chunk of justice keeping karmic balance in the center, and that’s what he did. By his own rules of his own universe, Spillane crafted experiences. You’d taste the blood, feel the sweat, smell the danger. You were there along with detective Mike Hammer and you’d better be grateful for that, because otherwise you wouldn’t be getting out alive.

But once you remove Hammer from his element — from his necessary context — you see other, less admirable sides of him that the novels kept hidden. It takes no work to recontextualize the man as a vindictive, reactionary bully; all one needs to do is view him in isolation. Hammer shifts immediately from being a heroic figure to a sociopathic and dangerous one when you take no more than one step back from the action. Aldrich saw that, and crafted his film around the distance between what Mike Hammer thinks he is, and what he actually is.

Ralph Meeker plays our thick-skulled protagonist marvelously; more than half a century later I’m not convinced the screen has ever had a better portrayal of unearned, unchecked confidence. Hammer — on the page and on film — is a legend in his own mind. The difference is that on film we shy away from him. He question him. We wonder if his brutal, abusive, gleefully cruel methods are, strictly speaking, necessary. Meeker portrays him as a man who knows everything, except what the hell he’s doing.

Whereas Spillane never noticed (and whose success as an author hinges upon us continuing not to notice) that Hammer was a violent numbskull, Aldrich makes that the primary conflict of his film. His version of Hammer is a protagonist he positively dares us to root for. “Go ahead,” he says. “Follow this guy. See where it gets you.”

Both versions of the story open the same way. Driving alone at night, Mike Hammer nearly strikes and kills a panicking woman. She’s naked apart from a trenchcoat, and he gives her a ride away from whatever it is that she’s fleeing. He learns that she’s escaped from a mental institution, and at a service stop she mails a cryptic letter to him…just in case she doesn’t survive the night.

Sure enough, she doesn’t. Hammer is run off the road by a group of goons who kill the woman while torturing her for information that she never gives up. They then shove Hammer’s car off a cliff — with an unconscious Hammer and the woman’s corpse inside — and when he comes to, our hero sets out seeking answers of his own.

In the book, he picks up the thread fairly quickly. The woman had Mafia connections, and the men who killed her were trying to get their hands on two million dollars worth of drugs. The identity of the MacGuffin comes to light relatively quickly and easily, and Hammer spends the bulk of the novel trying to track it down before the Mafia does.

The film, however, plays it coy. Hammer doesn’t know what he’s chasing down until he finds it. In fact, he doesn’t even know what it is until well after he finds it. It’s not a cache of illegal drugs, and he’s not up against the Mafia. No…compared to the actual situation he finds himself — too late — embroiled in, those things would be a comforting reprieve. He’d trade every ounce of his reality to be at the mercy of the Mafia, because what he finds instead is something even he can’t convince himself he can handle.

Staring into the cold eyes of organized crime is nothing, after all, when compared to the raw, undiscriminating, destructive power of the Manhattan Project.

I started reading Kiss Me, Deadly as I was finishing Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep (which will likely be covered here at some point, but not the version you’re thinking of). It was a nice opportunity to compare and contrast the way Chandler and Spillane handled their signature characters.

Both Philip Marlowe and Mike Hammer operated outside the law, and they each viewed themselves as a lone kind of justice in a world that desperately needed them. But, operationally, that was where the similarities ended…and I think reading Kiss Me, Deadly and The Big Sleep so close together illustrated that quite well.

As The Big Sleep comes to a close, Marlowe’s client — the dying Colonel Sternwood — is made aware of the fact that Marlowe lied and misrepresented himself while working on the case. “And do you consider that ethical?” Sternwood asks him, clearly rhetorically. “Yes,” Marlowe replies. “I do.”

If, ultimately, it serves his client well, Marlowe is willing to bend the rules. It’s an adherence to a kind of ethics; one that may not match up with yours or with mine (or with Colonel Sternwood’s), but one he can justify to himself. One that allows him to look in the mirror and see a man he respects staring back at him. Marlowe is the damaged and weary heart at the core of his stories, the character who elevates Chandler’s novels above mere works of detective fiction and allows them to become complex, interlocking character studies. Marlowe will do the wrong thing in service of the right thing, and hate and admire himself in equal measure for it.

As Spillane’s Kiss Me, Deadly opens, Mike Hammer outlines his own code of ethics. He explains to his secretary Velda why he’s going to see this dangerous case (which nobody hired him to investigate) through to its end: “I hate the guts of those people. I hate them so bad it’s coming out of my skin. I’m going to find out who ‘they’ are and why and then they’ve had it.” Importantly, he grins at Velda before he says this.

His code of ethics? Fuck you; that’s his code of ethics.

Hammer takes joy in hatred. He relishes it. He’s fueled by vengeance and bravado. And for Spillane, that’s enough. There’s no need to explore or undercut his attitude; it’s Hammer’s. If you don’t like it, you can shove off and find another book.

Flawed heroes by no means suggest “lesser” works of art, but the author must be aware that his heroes are flawed. Spillane, clearly, is not. He operates on Hammer’s side, watching him booze and batter and romance his way along the sunny California coast. In Spillane’s mind, that’s what Marlowe did, too. And he’s right…except that Marlowe suffered for it. Sure, Hammer comes away beaten and bruised, but Marlowe slinks back to his lonely apartment to play chess alone and wonder why he’s still alive. Marlowe’s suffering is emotional, spiritual, psychological. Hammer’s is expressly physical. Spillane doesn’t see a difference. I find it hard not to.

This is probably a large part of why Spillane’s writing hasn’t seen the kind of critical reappraisal that Chandler’s has. For all of their superficial similarities, the fact is that Chandler wrote about terrible things with a kind of love, a jilted affection, a hopeless hope for a better — or at least a decent — tomorrow. Spillane wrote about the same terrible things with a frothing hatred, a frenzied desire to inflict revenge until the karmic tally balanced out. One of those approaches proved to resonate through the years. The other, flatly, didn’t.

Spillane’s blindness to the weakness of his own prose is what holds the Mike Hammer novels back from critical recognition. Spotlighting that blindness is what allowed Aldrich’s adaptation to achieve it.

In the film, Hammer is portrayed as the worst kind of man; an imbecile who won’t keep himself in check. And Aldrich also gives him an identifiable reason for that: greed. Hammer on the page is a successful private eye. Sure, he don’t play by no rules and a couple-a noses get busted here ‘n’ there, but he ultimately proves himself correct. He gets his man. His methods are vindicated. Importantly: he wins.

Meeker’s Hammer doesn’t seem to have won in a long time. He might never have won. Sure, he’s got the charm, the nice suits, the sexy secretary. He’s got the sideboard full of booze. He’s much like his textual counterpart in those ways. But part of the reason he gets wrapped up in solving the mystery — what Christina Bailey, the mysterious woman, knew…what she was killed for knowing — is that he imagines a substantially larger payout than he usually gets. See, in an early — marvelously tense — scene, a board of inquiry grills Hammer as soon as he gets out of the hospital. And it’s there that we learn, if we couldn’t tell already, what a shit he is.

Christina Bailey’s dead. Hammer gave her a ride that night and lied to police at a roadblock to keep them from knowing that fact. Later they find her corpse and Hammer’s unconscious body in the wreck of his car. He’s obviously peeved to be asked about it, but you can hardly blame them for treating him as a lead.

He refuses to talk, however…so they talk for him. We learn that he’s what they call “a bedroom dick.”

He hounds out infidelity by creating it himself. He schmoozes the wife, and he sics Velda on the husband. They dig up whatever they can and sell the information to the other spouse.

He’s not an honorable man seeking justice; he’s a lowlife with dollar signs in his eyes. He’ll knowingly and deliberately hurt others and interfere with their relationships in order to maintain his station in life.

He sits there while the investigative committee asks him questions and tries to prod a response out of him, but when you’re comfortable with being that much of a jerk, you’re beyond the reach of insult. Their sharp words about his business practices don’t seem to faze him at all. No surprise there, and as its main purpose in the film is background exposition I admit the scene doesn’t faze me much either.

Aldrich, however, doesn’t leave it there. We get a much more affecting reprise of the theme later on, when Hammer lets himself into Velda’s apartment late at night. She’s in bed…sweating and unhappy. She reports to him about the man he sent her out to see, and we see that she’s not happy with the way Mike essentially functions as her pimp.

Maxine Cooper’s Velda is a harrowing creation…all vulnerability and desperate to please. She’s a beautiful woman with a good heart who is trapped in a toxic arrangement with her boss. It’s off-putting, disgusting, and perfectly handled by the film. Throughout Kiss Me Deadly she worries about Mike. She worries about his safety. She advises him not to dive head-first into a search for something people are dying over and which he can’t even identify. (Not bad advice, you have to admit.) But here, for perhaps the only time, she’s worried about herself.

She doesn’t want to say so. And she never does get around to saying it directly. But the toll that this “dating” is taking on her is clear. She uses the four-letter word “date” in place of another four-letter word films might use today. She feels filthy and disappointed in herself for having to “date” these men simply because her boss tells her to, and tonight’s brings her pretty close to the breaking point. All we need to know is expressed in her shivers, in her unfocused, desperate rambling.

“He…tried to date me,” she explains to Mike, who is only half listening. “With a few drinks…and one thing leading to another…I suppose I could get some more information…”

She’s hoping, clearly, that Mike will tell her she doesn’t need to go any further. She’s keeping the door open for him to say exactly that. We get the sense that she’s always leaving this door open…and that he closes it every time.

When he doesn’t respond, she asks him outright: “Do you…want me to date him?”

It’s in line with his narrative treatment of her in the book. Hammer is constantly proud of having such an attractive girl on his arm. He relishes the looks other men give her. For lack of a more tactful way to put this, he gets off on it. Strangers stare at Velda getting into and out of cars in Spillane’s version of Kiss Me, Deadly, and Hammer couldn’t be more proud of himself. They’d kill for the chance to touch her, but he knows she’s never leaving the palm of his hand.

Velda isn’t his wife, his girlfriend, or his love interest. She’s a pet. She’s someone over whom he exercises control, right down — as the film assures us — to who she fucks, and when, and for what purpose.

He toys with her across both media, but only the film gives us a scene like this, in which she’s on the verge of breakdown while her concerns are ignored. Sure, by this point in the film we knew he was a bedroom dick. There are no narrative surprises here. But the toll it’s taking on Velda has the capacity to shock. To upset. To revolt. And it does all three.

It’s scenes like this — raw with unspoken pain — that remind us that though Kiss Me Deadly is having a lot of dark fun with the troubling conventions of noir, and is at least passively interested in exaggerating them so we can see how ugly and ridiculous they are, we aren’t watching a parody.

There’s a lot of great comedy in Kiss Me Deadly, but it’s hard to laugh, because there’s a lot of hurt and anguish and crushed innocence as well. No, in spite of its inversions and subversions and intentions to tease out each of the genre’s many hypocrisies, it’s not a parody; it’s a serious film that just so happens to star a jackass.

Funnily enough, Aldrich’s adaptation tones down Hammer’s jackassery. It’s sharper and more critical in its development and presentation of the man, but a large amount of awfulness is actually excised from the character. Mickey Spillane was unsurprisingly unhappy with the way Hammer was portrayed in this film — an unhappiness which may have led the man to portray the character himself in the eventual adaptation of The Girl Hunters — but he should have been happy that his most troubling material never left the page.

There’s his treatment of Velda…which does largely carry over, but is missing an integrally offensive scene in which he assures her that, as a woman, she is incapable of taking care of herself. This, mind you, while he’s sending her out on what he knows is a dangerous mission. (Some pep talk, there, Hammer.)

In both the novel and the film, Velda ends up kidnapped and ultimately rescued by Hammer. In the film, however, that at least manages to play like poor planning on the part of the detective, whereas the book has an inherent “Told ya so” attitude to the development of her going missing. And, like Spillane playing Hammer in The Girl Hunters, the moral of that part of the story seems to be “If you want it done right, do it yourself.” Neither Spillane nor Hammer could trust the delicate business of slapping a city around to lesser people.

But there’s more to Hammer than the shitty way he treats Velda. For instance, there’s the shitty way he treats everyone else on Earth.

The novel sees him following clues that lead to an apartment. When he tells a woman in the building that he’d like to see the superintendent, she informs him that she is the superintendent. He tells her he wants to speak to her husband, then, because she’s nothing to him.

It’s only mildly stomach churning until the climax of the scene, in which Hammer’s behavior inspires her husband to start being dismissive of her as well. In fact, her husband shutting her down plays like a triumphant moment…one we’re meant to enjoy, and one which is meant to reinforce Hammer as being the hero.

Look! He just helped this guy in his marriage! Before he met our heroic private eye, this guy was probably treating his wife as some kind of equal!

Now, of course, we need to take into account the time during which the book was written. That’s the same reason we didn’t get into the socially problematic portrayal of “the black boys” in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and it wouldn’t be fair to deride Kiss Me, Deadly for being complacent in its sexism when it was published in the early 1950s.

However there’s a difference of intent between scenes like this and a background level of sexism: Spillane’s work isn’t merely comfortable with or accepting of the treatment of women in 1950s America; it celebrates it. Spillane has Hammer right wrongs by showing uppity women their place. He makes sure they stay where they belong, and don’t get any big ideas. He equates their silence to a necessary male triumph, and that’s the difference.

A novel like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest can contain a problematic portrayal of black people as residue of the culture in which it was written. By contrast, a hypothetical novel that celebrates segregation and sees its hero organizing lynch mobs to keep blacks in line cannot fall back on the same excuse.

The superintendent moment does have an analogue in the film, but it’s much shorter there, and is at least played for laughs. It’s also one small part in a much larger, more artistic work that conclusively condemns Hammer’s behavior, which is important to keep in mind. The same scene that makes the woman look like a bitch in one context makes Hammer look like a bastard in the other.

We also see sexism manifest itself in a bizarre way through the character of Michael Friday. Michael is female, and in the book there’s some back and forth about the fact that she shares her first name with Hammer. However nothing really comes of it, making it seem like Spillane started telling a joke and forgot to get to the punchline, which is why her incarnation in the film is just named Friday (and is that much better for it).

In both versions, Friday is the half-sister of Carl Evello, a dangerous cog in the machine Hammer is attempting to dismantle. However her film incarnation doesn’t have anything to do with the plot after Hammer flirts with her and uses her fondness to gain access to Evello’s estate.

And that’s fine. After all, even the best detectives in these kinds of stories need to use and manipulate others. A little bit of eye contact and double entendre over hard drinks is nothing. Hammer knows that Evello won’t be happy to see who’s schmoozing his sister, so there’s a psychological element at play here in addition to the simple, logistical one. In a Marlowe story we could question the ethics here (and there’s no doubt Marlowe would question them himself, alone at night in his empty apartment), but we already know that Hammer doesn’t have a code of ethics; he wants to win and doesn’t want to lose. It doesn’t get any deeper than that. Keeping that in mind, his treatment of Friday in the film is about as positive as one can ever hope to see.

In the book, however, both he and Spillane have bigger plans for her. She gets involved — and used as a pawn — in the conflict between Hammer and her half-brother. He gets information from her. He strings her along romantically (though it does appear, at times, that his feelings for her are genuine). And, ultimately, he sends her off, deeply entangled in a situation she wishes she knew nothing about, on a fact-finding mission that is likely to get her killed. She goes…and we never hear from her again. There’s no resolution, and she is apparently murdered on this mission without Hammer ever following up to rescue her or to make sure.

It’s an uncaring end for a character that seemed integral to the novel, and it gets even less caring when Hammer reveals that he’s mainly disappointed by her death because he’ll never get to fuck her. All that foreplay for nothing! Our poor hero. Fortunately, though, when he rescues Velda his first thought is that he will fuck her, so I guess everything worked out after all.

In fact, in the book Hammer has a habit of going through femme fatales like dental floss.

The character type is a staple of the genre, but when they keep getting introduced and killed on his watch — the mysterious woman at the beginning, Michael Friday at some point off camera, Lily Carver toward the end of the book, very nearly Velda — it borders on unintentional self-parody. Spillane never realizes how ridiculous it feels to read this.

Introducing one femme fatale and immediately disposing of her — as with the mysterious woman at the novel’s beginning — works as a shock to the reader’s system. That’s the reason Janet Leigh’s structurally untimely death in Psycho hits the way it does; we meet a character and believe, at least to some extent, that we know what to expect from her arc. When an outside force — the unseen passengers of another car, Anthony Perkins — derails that character’s trajectory, we feel it. We have our sense of security shattered. We feel lost…and there’s nobody’s hand to take but the storyteller’s. We are, as they say, in their grip.

It’s an effective method of audience manipulation, but Spillane keeps doing it…and numbs its impact. It becomes comical at best, and a reminder that Spillane isn’t totally in command of his material at worst.

And all of this doesn’t even touch on the violence throughout the book. While a fair (okay…a more than fair) amount of violence is to be expected in hardboiled detective fiction, it’s typically violence that occurs to and around our detective figure. That, after all, is what separates him (and it is always a him) from the bad guys.

Not so in Kiss Me, Deadly, in which Hammer takes a dimaying pleasure in causing others pain. About midway through the book he murders two people who have designs on his life…which makes sense and was likely necessary. Less sensical and by no means necessary is what he does next: he arranges their dead bodies in a “cute” tableau against a sign reading DEAD END. Like James Bond, Hammer is always ready with a quip after besting his adversaries, but I don’t recall Bond’s sense of humor stretching to include the desecration of corpses.

He also confronts a character, Dr. Soberin, toward the end of the book, and kills him in cold blood rather than turn him over to the authorities. This after he breaks all of Soberin’s fingers just for the sport of it. And at another point he searches for the man he believes has taken Velda, and anticipates “the pleasure of killing him slowly.”

In Spillane’s world, though not in Spillane’s perspective, the hero’s actions are indistinguishable from the villain’s. The only real way to tell them apart is that one of them has the benefit of first-person narration. If we were watching from an outside perspective, the line between them would grow hazier, and eventually non-existent. Villains, by their natures, like to drag pain out…inflict it with gusto…relish the agony. Hammer, by his nature, appreciates the same things on the same level.

He’s ostensibly on the side of justice, but he believes that everyone should be able to appreciate some good, unnecessary torture. (Dick Cheney was a huge fan of the Hammer bibliography.) Chandler would definitely have said that Marlowe was a flawed man, but Hammer makes Marlowe look like Barney the Dinosaur.

These are all things that don’t carry over to Aldrich’s film. His version of Hammer — the one so gloriously, smugly inhabited by Ralph Meeker — is informed by this behavior, this mindset, this callous disregard for the feelings and needs and respect of others, but he does Spillane a favor by eliminating Hammer’s more sociopathic excesses.

It’s a favor Spillane could only repay with spite and vitriol, but had Spillane allowed himself to view Meeker’s portrayal as the kind of guy Hammer would be in real life, he’d have gained invaluable perspective.

One of the most interesting structural changes in the adaptation is the role of Pat, a police offer attempting to untangle the same web of clues Hammer is. In the film, which I saw first, Pat embodies an identifiable — almost necessary — type of character: the adversarial lawman.

Our lone wolf detectives may always get their men, but in order to do so they need to operate on their own terms. This is where the lawman comes in. He warns the detective to leave the job to the guys with badges. He may threaten our hero’s safety. And while he may be either honorable or crooked, he represents an approach to crime solving that is hindered by its own process and procedures. A private investigator answers to none of that — though he may ultimately have to account for it — which is why PIs are so often the heroes, and straight-laced emissaries from the precinct so rarely are.

In the film, Pat seems to fit that adversarial role quite well. Aldrich has him do all of the things we’d expect: warn Hammer off the case, try unsuccessfully to get Hammer to share the information he’s uncovered, and, ultimately, shake begrudging hands with the resourceful man who solved the case before the boys in blue could.

…only we never get around to that last part, because all Hammer succeeds in doing is leading the bad guys to the dangerous nuclear material they’ve been chasing, and obstructing the official investigation that could have stopped them in time.

Hammer’s army-of-one approach to the case is precisely what bungles it, as sharing even the most basic information would have immediately made the scope and nature of what was happening more clear. In perhaps the most obvious example, Hammer tracks down Lily Carver, the frightened roommate of the recently deceased Christina Bailey. He spends the majority of the film with her, sheltering her and protecting her as he chases down his leads. When she disappears toward the end of the film — conveniently after he discovers the location of the stolen nuclear material — he mentions her to Pat…and Pat replies immediately that Carver’s body was found a week ago.

Hammer realizes then that he’s been used…that he’s the reason the bad guys are going to win. The smallest sharing of information, the narrowest attempt at cooperation, would have prevented this. Hammer was too preoccupied with holding all the cards to realize that he’s been slipped a counterfeit. He took a lie at face value, and the human race is endangered for it.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves with that last sentence, there. All of this is meant to be compared to Pat’s role in the book, which is much different. In the film, he’s an identifiable archetype (albeit one who, subverting our expectations, knows what he’s doing). In the book, he’s Hammer’s pal.

Pat, on the page, is a hopeless boob. He’s ineffectual, and impressed (isn’t everyone?) by Hammer. He does his best to help Hammer and makes only token warnings about his safety. He calls in favors with the other officers and he dutifully stays out of the PI’s way, knowing (as he must) that nothing can stop our hero.

Compared to Pat on screen, this is a much less satisfying character. Indeed, he only exists to remind us of the ostensible danger over which Hammer regularly triumphs; as we experience the plot through Hammer’s eyes, and Hammer is a vial of pure, distilled confidence, we need somebody else to tell us just how incredible he is for succeeding. Mike Hammer makes surviving the streets and single-handedly taking down the entire Mafia look easy…so if he’s to be our filter character, we need someone else to remind us that, no, actually that’s pretty hard; Mike Hammer is just that rad.

In the film, Pat knows better. He views Hammer the way most of us would in real life: as a putz who doesn’t know better than to get out of the way. In fact in both the book and the film, Hammer has his PI license and gun permit revoked. In the book, this is presented as the work of the powerful, connected Mafia who are pulling strings to keep Hammer off their backs, with Pat expressing worry and remorse over this development. In the film, however, Pat takes great pleasure in revoking that license and permit himself, and even issues a direct threat for disobedience: “If I catch you snooping around with a gun in your hand,” he says, savoring every word, “I’ll throw you in jail.”

The book wants us to believe that Pat and Mike are old friends who have earned each other’s respect over a lifetime of bailing each other’s asses out. The film knows better; no cop in the world would want, or would benefit from, an impulsive brute like Hammer dragging his knuckles all over a crime scene. And so the revocation of license and permit are a necessary first step for Pat in the film. Whereas his literary counterpart hopes Hammer can win in spite of the handicap, Film Pat personally handicaps him to keep him out of the way.

We even get a great line in the film that isn’t revealed as great until the ending puts it into perspective: when told to step aside and let the police do their jobs, Hammer asks, “What’s in it for me?”

He finds out too late, and so do we: he and a lot of other people would have gotten to stay alive. Hammer serves up the sort of confrontational attitude that is so often framed as a positive quality for detective figures, and the film then guides us through a long series of scenes that make clear that it’s a positive quality for nobody.

As he explores and teases out the mystery of Christina Bailey, we follow him along on a trail identifiable to any fans of the genre. He checks in with landlords, with friends. He hears a few names uttered in relation to hers and he tracks them down as well. He finds kindly old gentlemen, haunted family men, boxing managers. He assembles a network of willing and unwilling informants, and pieces together what they know. On the surface, it’s every detective we’ve ever seen before.

But beneath the surface, there’s something darker. We see it in how quickly Hammer gives himself over to anger. How cruel he can be, and how perfectly amused he is by that cruelty. In one scene he tracks down a man who may or may not have some information about another man who may or may not have some connection to Christina’s death. It’s a hunch several other hunches deep, but before he even asks a question he pulls a record off the man’s shelf, identifies it as “a collector’s item,” and snaps it in half.

Meeker’s look of smug satisfaction is perfect here. The man hasn’t withheld any information, nor is Hammer even sure he has any. He just sees the man’s extensive collection, pegs him as a music lover (the man was singing enthusiastically along to opera records when Hammer arrived), and decides to be a dick about it.

It’s one of the single cruelest moments in the film, because it’s one of the only times we know that a character truly cares about something. Hammer deliberately destroys it and leaves him with the pieces not because the man wouldn’t talk, but simply to assert himself. A man who had nothing to do with anything Hammer’s seeking has one of his prized possessions snapped in front of him, and Hammer couldn’t be happier about it.

His behavior is a far cry from Marlowe’s, as the latter is painfully aware of how rare goodness is in the world around him. When he finds those uncommon “straight” folks, he remembers them. When he sees how the world treats them for being straight, he’s tormented by it. Harry Jones in The Big Sleep is an example of a character with a good heart who doesn’t hope for anything more than to take another character away from all the madness and murder and misery. When Jones is killed before Marlowe can get to him, our detective feels the world grow that much colder. Hell, the entirety of The Long Goodbye could be said to focus around this idea, as Marlowe befriends Terry Lennox, a disfigured war hero the world — and seemingly everyone in it — beats down for no other reason than that they can. And when Marlowe learns later that Lennox himself isn’t such a great guy, either, it’s a charged, raw, painful revelation for him…a kick in the pants for being dumb enough to believe that goodness could even exist nowadays.

Compare that to Hammer’s treatment of a rare straight, honest fellow that he encounters in his travels: in both the book and the film, the desk clerk at an athletic club refuses to accept a bribe in return for information on one of its members. Marlowe, whatever his subsequent course of action, would be (at least temporarily) reassured by the knowledge that there still exists a kind of man who can’t be bought. Hammer, by contrast, grabs the man by the lapel and slaps the shit out of him.

This also highlights another difference of approach between the two detectives: Marlowe’s not a particularly big guy. He can’t count on winning a battle of sheer brutality, which ultimately results in a better character because it means he needs to outwit his opponents. On the page — where we can very clearly see the workings of mind but never the workings of body — this works very well. And where Marlowe out-thinks, Hammer overpowers. Both are valid approaches, but one is far better suited to the literary bent of the genre.

In fact, throughout Kiss Me, Deadly, Hammer reveals himself to be exactly the kind of guy Marlowe is regularly bringing down a peg. Someone with an inflated sense of self-worth without the ability to see that he’s ridiculous. And while this could — and should — rightfully feed a pride-before-the-fall approach to characterization, Spillane doesn’t see this as a flaw to begin with. Hammer just comes across as a meathead.

His dimwittedness is passive — and clearly unintentional — in the book, but Aldrich was a close and a respectful reader. He emphasizes Hammer’s intellectual failings, even as he reconstructs the central mystery to make it more satisfying.

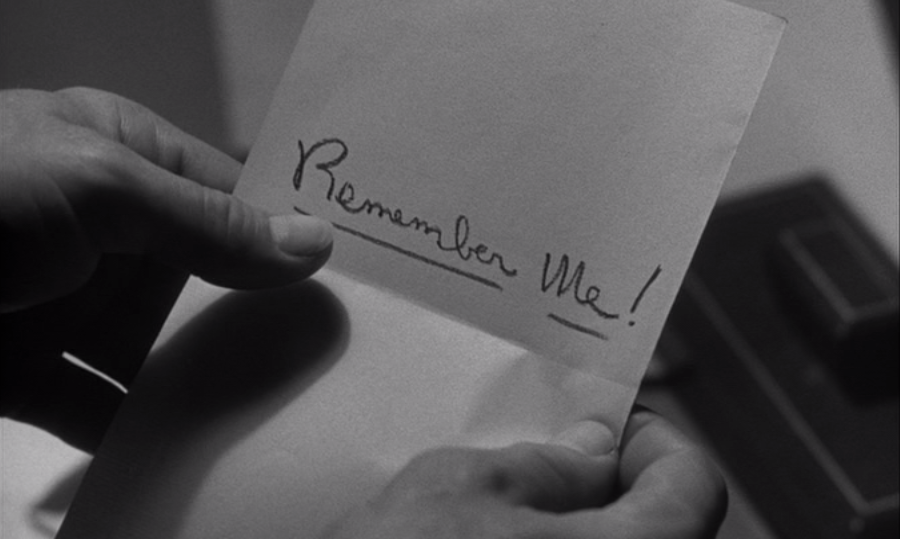

In both the film and the book, Hammer receives a cryptic note from the mysterious woman (played in the film by an unexpectedly sexy Cloris Leachman)…after her death. She mailed it from a gas station in the final minutes of her life, having gotten his address from his license in the car. So far, so similar.

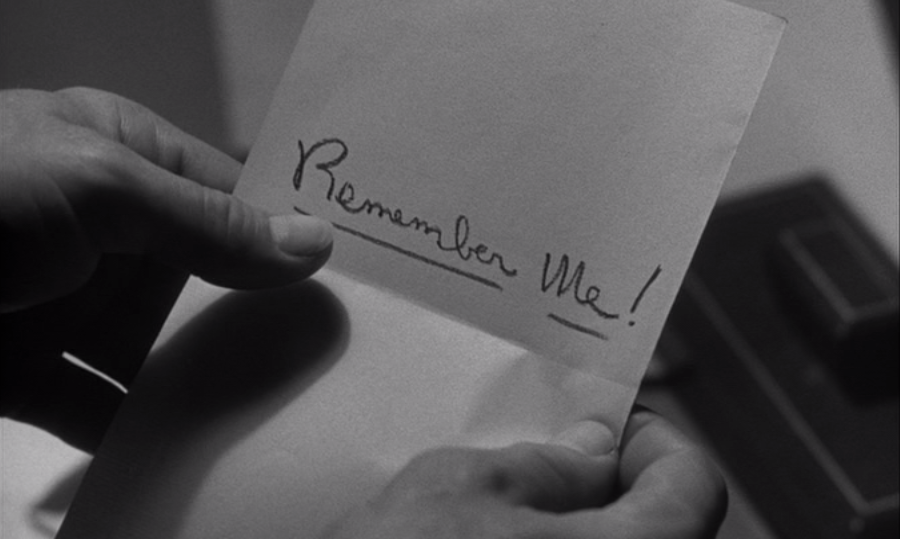

But the message in each case is very different. In the film, it’s two words long:

“Remember me.” That’s all. And yet…that’s not all. Because while she can’t spell out what she needs to tell him — for rightful fear that the note will fall into the hands of those seeking the nuclear material for their own nefarious purposes — she can hope that he’ll put several different pieces of information together and figure it out. He is a detective after all…right? That shouldn’t be such a novel idea…

And yet it is, because compared to Spillane’s original “mystery,” Christina’s message conceals its secret much more intricately.

There’s the note, of course. But the film adds layers. There’s also the way she introduced herself to Hammer: “Do you ever read poetry? No, of course you wouldn’t. Christina Rossetti wrote love sonnets. I was named after her.”

When Hammer goes to investigate Christina’s old apartment, he finds a book of Rossetti’s works…including one that begins with the words “Remember me.”

He pores over the poem with the woman he believes to be Lily Carver, Christina’s old roommate, and she helps him to decipher its meaning as it relates to Christina’s predicament. Hammer doesn’t realize it — though he would if he’d worked with the law rather than against it — but “Carver” has a vested interest in finding the item’s hiding place, too. In fact, she has more of an interest than even Hammer does; she actually knows what she’s looking for, and what it’s worth to others. Hammer, by contrast, is still chasing what Velda referred to as “the Great Whatsit.” By this point in the story he’s even sacrificed her to his search…without knowing what it is he will find.

Eventually, it clicks for him…and it clicks with the following lines: “For if the darkness and corruption leave / a vestige of the thoughts that once I had.”

He works through it:

“If it’s a thought, it’s dead because she’s dead. It’s got to be a thing. Something small, something she could hide. But where would she hide it? She didn’t have time at the gas station. She swallowed it!”

He heads to the morgue to demand an autopsy, where they find a locker key in her stomach.

That’s a mystery. And whether or not you buy Mike Hammer of all people stumbling upon the solution through impulsive poetry analysis (as much as I love the film, I’m not sure I do), it is a puzzle that gets solved. What’s more impressive is the way that Aldrich built all of this around Spillane’s source material.

He finds a real-world poet who has written a poem that can be boiled down to both a seemingly simple phrase and a deceptively rich clue…one that will lead his Hammer to the same conclusion Spillane’s found, but in a less direct and (dare I say it?) more “mysterious” way. It requires renaming a character (Christina Bailey was called Berga Torn in the book), but it’s worth it. See, because while I might have seemed like a smartass above about the novel idea of treating Hammer like a detective, Spillane didn’t really do it.

His version of the message is embarrassingly direct: Berga writes to Hammer, “The way to a man’s heart–” and leaves it at that, essentially structuring the novel’s central mystery around a Kiddie Korner fill-in-the-blank puzzle.

It’s especially (and again unintentionally) comical when both Hammer and the entire sprawl of the Mafia are angrily unable to solve it. It’s absurd that nobody in the universe of this novel has heard the idiom before (apart from Berga Torn, I suppose), and the net result is that we have a state-wide life or death scramble over what may as well be the solution to “Why did the chicken cross the road?”

In filming Kiss Me Deadly, Aldrich knew that wouldn’t fly. There’s more to a mystery than a withheld solution…especially one that the viewer would guess the moment the question is raised. He may have revealed Spillane’s central character to be a helpless dolt, but he had respect for his audience.

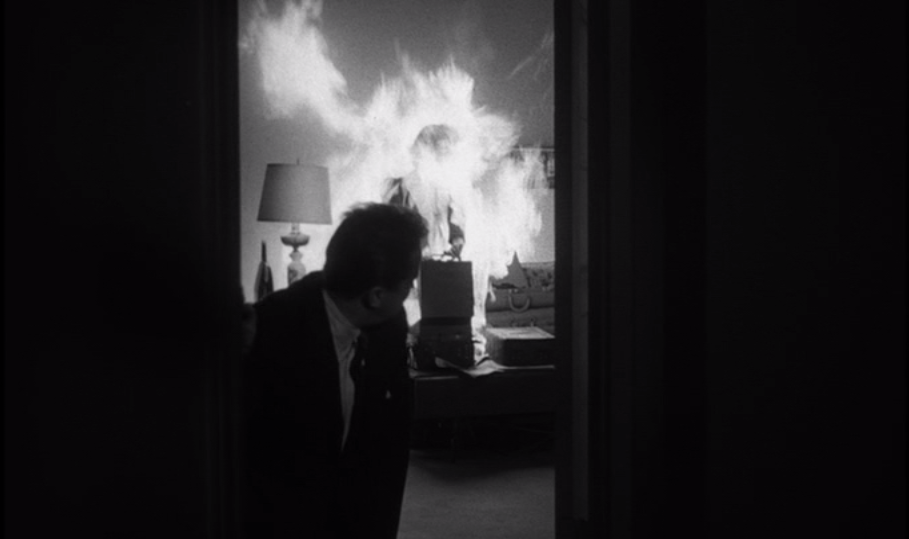

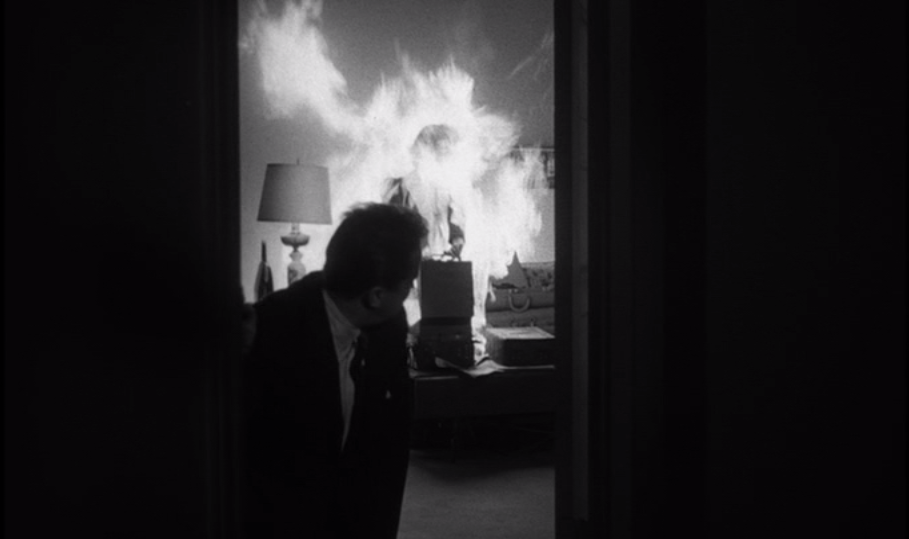

The final stretch of the film is christened by a scene in which Hammer finds the Great Whatsit and realizes he’s out of his depth. It’s a realization that literally scars him.

Having solved Christina’s dying riddle and arrived at the object of his search, Hammer locates the mysterious box in a locker at the athletic club. He relishes the approach, taking his time with the buckles and clasps that keep the case closed. He never questions whether his search has been worth it; his only question is how much it’s worth. The tension is high, but the stakes, as far as he’s concerned, are non-existent. He’s already here.

He’s already won.

So Hammer takes a well-deserved peek at his prize. It’s not a cache of drugs. It’s not a sum of money. It’s not even something that can be divided and sold: it’s unstable nuclear material, and a moment of panicked exposure is enough to disfigure Hammer’s wrist.

It’s also a moment that has resonated through the years, with the searing light of an unseen force being visually reprised in films such as Repo Man and Pulp Fiction. Hammer’s nightmare endures.

He jerks away, bitten and shaken by what just blinded and howled at him from a hiding place that suddenly feels far too exposed.

The injury to his wrist smarts, but one gets the sense through Meeker’s deeply affected performance that the real scar is psychological. However much it hurts on the outside, it’s the blow to his dignity, his confidence, his self-assurance that he’ll never recover from. He had this. It was right there. It was in his hands. And now he wishes to god he never found it.

Lily Carver, who made the trip along with him, goes immediately missing. The clerk at the athletic club is terrified. And Hammer can’t even turn to Velda, who’s been taken by the very goons who were searching for this dangerous weapon. The very goons that Hammer just led directly to it. The very goons who even did him the courtesy of coming to the bar to tell him they took Velda away…but he was passed out drunk when they arrived, and so he still doesn’t know who they are, or where to find her.

He’s some guy, that Mike Hammer.

He returns to his apartment and finds Pat, but there’s no more swagger, no more confidence in his gait, no more questions of “What’s in it for me?”

Meeker incredibly, deeply, disarmingly sells the emptiness. The hollowness. The complete and immediate wrenching change within. The distance between Charles Bronson and Al Bundy covered in the shift of an eyebrow.

Hammer is a broken, defeated schlub…all mussed hair and rumpled suit. His smug, self-satisfied grin is replaced by a hangdog sense of impending doom. He hasn’t just fumbled a case, or lost out on a nice payoff; he’s well and truly fucked a lot of people…and he can’t prevent the damage that’s about to unfold.

This is still Mike Hammer, but he’s Mike Hammer as Mickey Spillane could never imagine him: as a human being.

Pat is here with the upper hand, to rub it in, to remind him, and us, of what he’s done. He speaks with a gentle brutality throughout the film’s best speech…an expository patch that functions also as punishment for a misbehaving toddler. The Hammer who slapped and punched and abused his way forward has found the implications of those actions to be beyond his control. Pat rightfully lays into him without breaking his calm, which somehow renders the entire thing that much scarier.

“You’re so bright, working on your own. You penny-ante gumshoe. You thought you saw something big and you tried to horn in. […] Now listen, Mike. Listen carefully. I’m going to pronounce a few words. They’re harmless words. Just a bunch of letters, scrambled together…but their meaning is very important. Try to understand what they mean. Manhattan Project. Los Alamos. Trinity.”

Harmless words. Just a bunch of letters…scrambled together. There’s only the meaning we give them, but that meaning is very important. That meaning can change everything.

Mike, deeply abased, delivers the most fragile three words he’s ever said. They’re three harmless words. Just a bunch of letters. But their meaning is very important:

“I didn’t know.”

It halts Pat in his tracks. It’s the sort of thing that might have mattered this time yesterday. Now, at this stage, it’s too late. “You didn’t know,” Pat spits back at him. And then, “Do you think you’d have done any different if you had known?”

And that exchange…those two lines between two characters…betray a deeper, richer, more fascinating story on their own than the whole of Spillane’s source text managed.

Obviously the proper response here is that Spillane wasn’t interested in telling the same kind of story Aldrich is telling, and that’s okay. But there’s something reassuring about the fact that Spillane’s masculine, abusive cavalcade of triumphant violence didn’t last, while Aldrich’s dark, cynical undercutting of the same events did.

There’s a comforting reminder about the resonance of art, its staying power, its tenacity in outliving its inspirations and its creators. Its ability to take on a life and a legacy of its own. Books, movies, music, any kind of media will always have its comfort food, and that comfort is always fleeting…but art survives. It outlives the countless deaths around it. It carries forward into a world that has been somehow altered by it. It stands and remains a monument to itself.

While humanity fumbles and falls, a work of art is unchanged. It endures. It lives.

The end of the film sees “Carver” succumbing to her own curiosity and opening the box. The hungry force of destruction inside devours her as she burns and screams in agony.

It then devours the room.

And the house.

And the darkness of the night sky.

The destruction comes fast, and is unexpectedly thorough. Our hero is on the scene, but only to be made painfully aware of his own helplessness, his impotence in the face of a real obstacle. In his escape he finds Velda, but there’s no feeling of reunion, of relief, or of anyone living happily ever after.

Together they stumble onto the beach with the nuclear disaster unfolding at their backs, and they take what minor, temporary comfort they can in the ocean as the swelling, repeating blast beats down on the world around them.

In the book? Oh, the book ends with Hammer being deeply repulsed by the fake Carver, who reveals that her body is disfigured and therefore she wasn’t worth all the time he spent trying to fuck her. He sets her on fire and leaves her to slowly burn alive.

How that — that — resolution could be reworked to become this horrific nuclear nightmare is a genuine example of spinning straw into gold. Aldrich did a great job not of adapting Kiss Me, Deadly, nor of improving it, but of sounding its hollows. Finding what it said without saying it. Ascribing grand meaning to a bunch of letters, scrambled together.

It’s tempting to give Aldrich the benefit of timing…arguing that the social climate in which he made his film was different from the social climate in which Spillane wrote his novel. But in truth they were released only three years apart — the cultural blink of an eye — and nuclear anxiety didn’t look much different in 1955 than it did in 1952. It’s not a matter of Aldrich filming in a different world than Spillane was writing; it’s a matter of Aldrich being interested in reflecting the needs, the fears, the paranoia of the world around him, whereas Spillane, flatly, was not.

In Aldrich’s hands, the story was elevated from an effective though forgettable bit of pulp to a Cold War horror show with a modernized Pandora’s Box as its central metaphor, the entire mess fed through a warped noir filter.

He did a lot more, that is to say, than point his camera while characters recited somebody else’s dialogue.

He created something that outlived the novel. He created something that outlived Spillane and himself, and is destined to outlive Hammer. He created something that still shocks today, something that continues to ring with terrible, destructive power. Something that reminds us that the wrong person in the wrong place can wipe out everything we’ve worked to build…often without even realizing that he’s done it.

The world of the novel was fragile. It splintered under the barest touch. But in the patterns of those splinters, Aldrich found something of harrowing beauty.

Instead of ignoring Spillane’s shortcomings as an author, Aldrich spotlighted them. He didn’t hide the flaws; he rearranged them so that they’d form a statement. And he didn’t redeem Spillane’s creations…he quite literally blew them up, along with the entire genre.

Kiss Me Deadly is often spoken of as noir’s grand finale…the last word that could ever be said on any one of its subjects. It’s a daring, definitive piece of punctuation that doesn’t only wrap up its own story, but seems to wrap up the stories of every hardboiled gumshoe, every dangerous dame, every nobody who’s ever been in over his head. It’s a blaze of glory that irreversibly consumed the genre that had given rise to it.

It was a great trick…but as Daffy Duck once observed, you can only do it once.

Kiss Me Deadly

(1952, Mickey Spillane [as Kiss Me, Deadly]; 1955, Robert Aldrich)

Book or film? Film. So much for all that “the book is always better” talk, huh?

Worth reading the book? If you’ve read all of the Chandler and Hammett and Cain you can get your hands on, then maybe.

Worth watching the film? Definitely.

Is it the best possible adaptation? Not only is it a better adaptation than the book deserved, the film makes a strong case for being the most intelligent noir in cinema history.

Is it of merit in its own right? The film is of merit, I’d argue, even to those who dislike noir. It’s one of the most daring and least apologetic adaptations I know of, and is a quietly damning study of Hollywood male bravado.