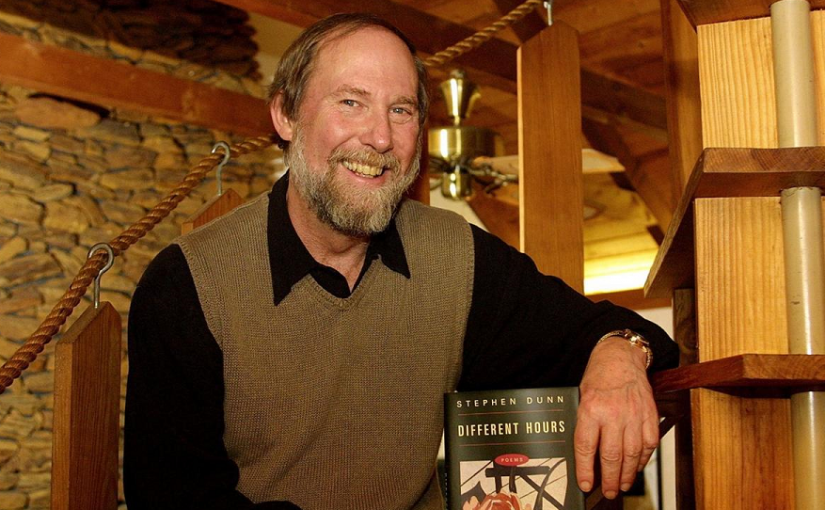

I was devastated to learn this morning of the recent passing of Stephen Dunn. To many, he was a name in poetry collections. To others, of course, he was a friend. To me, he was a mentor.

I’ve had the good fortune of being encouraged in my writing for just about my entire life. Teachers and colleagues and friends all encouraged me in my work. I was told that I was good, then I was told that I was very good, and at some point I started to believe it. By the time I enrolled at the Richard Stockton College of New Jersey (it’s a university now), 22 years ago, I was already a writer.

Not really, but that’s the answer I would have given you if you’d asked.

Stockton had a top-notch literature faculty. I am confident that that fact has not changed. But Stephen Dunn was its crown jewel. He was a celebrated poet, and he taught writing workshops. I was told many times to take one of them, and I did as soon as I could. They were small courses — around eight students — and they met for single four-hour sessions each week. I made several lifelong friends in that workshop. I am pretty sure I also made the best friend I’ve ever had.

And I found my mentor in Dunn himself.

Previously, I’d been supported in my craft by folks who complimented me, encouraged me, inspired me to continue. There is, obviously, value in that.

Dunn supported me by doing what others should have done sooner: He challenged me.

I say others should have done it sooner because I wasn’t prepared for this. I took challenge as an affront. And, as he was a perceptive human being and an accomplished writer himself, I’m confident in saying he knew I would take it that way.

Dunn would weed out students who didn’t belong in his workshops. That may sound harsh but I don’t believe it was. I remember the class consisting of a certain number of students on day one, and a smaller number on day two. He met with us individually, and some of us didn’t come back. I assume this is because students ended up taking the workshop for no reason other than to earn credit hours, and that’s not what the workshop was for.

The workshop wasn’t for those who dabbled. The workshop was for writers who needed to grow.

He never once suggested that I leave the class, but he also never once let my writing get away with its weaknesses. He would discuss — in front of everybody — what I did wrong. Where my language fell apart. Where I reached for a conclusion without finding one. Where I told without showing. Where a joke fell flat. Where a story started or ended at the wrong point. He wasn’t picking on me. This was the format of the class. We would all “workshop” each other’s stories, with the only real rule being that the authors of those stories could not speak until the workshopping was complete.

I remember seething. I remember being ready to pounce on every criticism. I remember wanting to explain why they were wrong as readers and I was right as an author.

Then it would be my turn to speak, and I’d have nothing to say. Because they weren’t wrong. For the first time, and thanks to Dunn, I was able to see not just that I had failed my readers, but exactly how I had failed them, and to what degree, every single time it happened. That was a gift beyond value.

It was a painful gift, but a necessary one. The encouragement I’d received in the past was nice, but it didn’t help me to grow. People focused on what I did right and made me feel good about it. Dunn, I truly believed, sensed my mindset, understood it, and worked to help me see my own flaws. He didn’t need to do that. We could have read my stories and moved on. But we didn’t.

At times I felt as though I were being unfairly singled out. Stories that were clearly lesser than mine were getting less scrutiny. Writers who slapped something together an hour before the class got a superficial reading and no more. My stories were discussed and dissected and ripped apart before my eyes.

It’s easy now to see that this was an enormous compliment. The fact that he gave my stories the spotlight that he did was not an insult. It was not an excuse to trample them. It was an opportunity for them — and for me — to develop. Other stories got less scrutiny because there was less to scrutinize. They received less effort because the writer had invested less effort.

I gave my stories a tremendous amount of effort. He knew that. I also thought I was a really fucking good writer. He knew that, too.

But if I wanted to think of myself as a really fucking good writer, he was going to correct me. And so he gave me a choice: Either I actually become a really fucking good writer, or I shut my mouth about it.

It was up to me. I could do either. If I wanted to take the easy way out, nobody would have judged me or ever thought about me again. If I wanted to actually become what I thought I already was, he would help me.

And so he did. He did so by stripping my work down to its component pieces — in front of an audience — and showing us everything that misfired. He offered suggestions, yes, but he never dictated solutions. There was no one way to write a story correctly, but there were a handful of ways to write them incorrectly. He painstakingly dismantled everything I did and handed me the pieces and told me to put it back together again…only he wanted it to work this time.

It wasn’t an approach that worked for everybody. A few more students left the class. I have a feeling that happened every semester. They probably thought they were really fucking good writers, too. And though the class ended at about 10 pm and many of us had work in the morning, I think various smaller groups of students congregated after every session to blow off steam.

“Can you believe he said that?” would be more or less the sum of our conversation, repeated dozens of times until we were too tired to stay awake. I think all of us understood that there was value in the experience — we kept coming back, didn’t we? — but it felt good to pretend we didn’t, to embrace the perceived affront, to do our impressions of Dunn and laugh. (Joke’s on you, you soft-spoken, deeply intelligent man.)

That was probably the hardest period of my life as a writer, because I was made to wonder if I should even be a writer. I mean, I knew I should. Of course I fucking knew I should. I’d been writing since I was around 10 years old, and seriously so since I was around 16. I knew what I was doing. I was good at this. This was all I had. If I weren’t good at this…if I were wrong and I actually weren’t a writer…

…what was left for me?

I remember one specific story that I wrote, which was absolutely destroyed in the workshop. It was called “Strength in Numbers,” and I certainly hope nobody still has a copy of it.

It was beyond salvage. Well, maybe not. Maybe an actual writer could have salvaged it. But me? No. It was very clear that I was not the person to restore this thing to life. Better to bury it in the yard and feign ignorance when the police started asking questions about where it was.

But that wasn’t an option, short of dropping the class.

We were responsible for taking one of the stories we’d written and shepherding it through to the end of the semester. We’d share a draft with the group, rewrite it, and then reveal the final product, improved for all of their feedback.

“Strength in Numbers” might be improved (hey, how could it not be, right?) but it certainly wasn’t going to be anything worth showing off. So I gathered up what little was left of my dignity and I sat down and decided not to rework my failure after all.

I wrote a different story under the same name, which itself was about a story called “Strength in Numbers” and the author who, despite his frustrations, couldn’t get it together. He spent more time being frustrated about that fact than he did working on the story, of course. That ended up being my main, unspoken joke. I wasn’t deliberately criticizing myself — this was a character, you know — but I was certainly relieving a lot of stress and anxiety by doing it.

I turned in the new draft as my “final” version of a completely different story. My classmates read it. We talked before Dunn showed up. One of them, I remember well, said Dunn was going to kill me. I felt the same way.

When Dunn did arrive, he sat down in his chair, held my story in front of his face and took a moment, as though his eyes were focusing on something he were seeing for the first time. He cleared his throat. All of this was standard practice as he decided how to open the discussion. I remember specifically seeing a little smirk appear on his face, and then he said, “I really liked this.”

Probably not in the way he expected, I gave him what he wanted: a story that came from somewhere. It wasn’t just a few pages of language I thought was clever. It wasn’t some pointless story I wrote because I was assigned to write one. It wasn’t the bare minimum skeleton of a narrative, which he and I both knew I could scrape together in my sleep.

I’d written a story. I’d written a story because I had an emotion that I needed to exorcise. I’d written something that mattered to me. And that was what I had been missing.

Dunn knew that I was capable of sitting down and pounding out something that read well, was funny, was probably even a little bit interesting.

But none of it mattered. I could play all of the notes of a beloved tune but I wasn’t playing them with feeling.

He pushed me until I realized that. And when I demonstrated that I understood that, he celebrated my work in front of the class. In front of me.

I’d met him halfway. I enrolled in his class expecting my writing abilities to be recognized. Instead, he recognized how much further they could go. That wasn’t what I wanted to hear, but he was right. So I brought them further. I worked to bring them further. I hurt myself bringing them further. And he thanked me.

I remember well one thing he said. He said that I arrived in his class as a talent, and I left as a writer of stories.

I remember it well because he wrote it in the foreword for my first collection of writings. He didn’t need to do that, but he said he was honored to do so. I believe that he meant it.

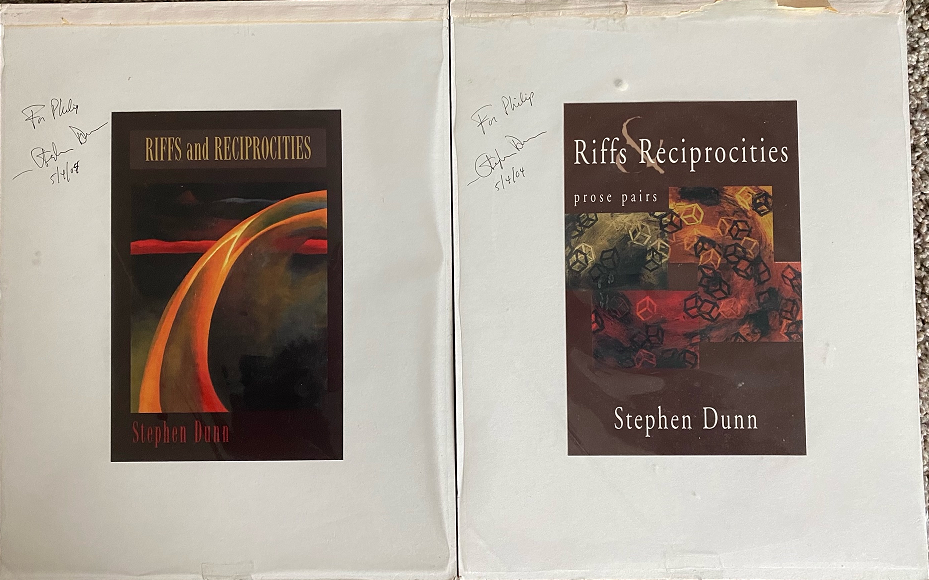

Years later, when he was clearing out his office, I happened to meet with him. He’d recently dug up some concept art for the cover of his Riffs & Reciprocities collection. I admired them and he asked if I wanted to keep them. Now I was honored. He signed them for me. I still have them. I will always have them.

I’ve seen him many times since. Sometimes live, as during an impassioned reading he gave shortly after 9/11, a reading that stuck with me so vividly that I ended up quoting it in my Resident Evil book last year. He is thanked in the book as well, for reasons even here I cannot overstate. I refer to him as “the great poet,” not only because he was one, but because he was and remains the great poet for me.

I took a second workshop with him shortly after he won the Pulitzer Prize in 2001. We kept in periodic touch after that. He helped me and he encouraged me and all of those things are wonderful, but I am only where I am — wherever I am — because he pushed me.

Dunn was not an easy man to love as he pulled apart what you thought was talent and revealed it to be mere competence. (At best.) But somewhere, at some point in his own creative life, somebody must have done the some thing for him. Somebody must have said, “Here are your weaknesses, Stephen, and you need to fix them.” And it must have stung. It must have angered. It must have lit a fire in him that kept burning right up until Thursday, June 24, his 82nd birthday.

The fire that Dunn lit within me — lit from his own flame — still burns. It will continue to burn. I feel it burn every time I write something. Every sentence. Every word, if I let myself feel it. I remember Dunn and how he would have pushed me to do better. Not because he wished to feel superior or to make me feel inferior, but because both he and I knew that I was capable of doing better, and because — of the two of us — only one was brave enough to point it out.

He guided me long beyond those writing workshops and he’s guided me probably long after he’d forgotten me. But I’ll never forget him, his demeanor, his unwillingness to let his fondness for his students get in the way of his honesty. I’ll never forget everything he said to me that I needed to hear. I’ll never forget the way he helped me take a knack for writing and turn it into a passion.

More than any one specific person in my life, I owe Stephen Dunn my career. If it weren’t for him, for him showing me not only how to stoke that flame but teaching me the importance of keeping it lit, I’d have moved on from this hobby like I have so many others.

Instead, writing stopped being a hobby. It became a purpose.

Everything I write has the voice of Dunn behind it. If it’s strong, it’s because I listened to him. If it’s weak, it’s because I didn’t. But it’s always there. It always will be there.

The voice of a man who tore me down because he knew I could build myself up better.

And because he cared that I do so.

Stephen Dunn invested himself in me. I hope I haven’t let him down.

Goodbye, Stephen.

Nothing I can say could possibly be enough, but I hope that some day I can leave with someone even a fraction of what you have left with me.