Note: This article contains big spoilers for the video games Prey and Soma. They’re both very good games and I encourage you to play them. While I know you will still find a lot to enjoy if you have something spoiled ahead of time, I encourage you to play one or both of them before reading on. That’s because if you read this first, there will be something the games cannot teach you, and which you may therefore never learn. You’ve been warned.

Note the Second: This article also contains comparatively minor spoilers for Maniac Mansion, Fallout, Fallout 3, Telltale’s The Walking Dead: Season One and a few others.

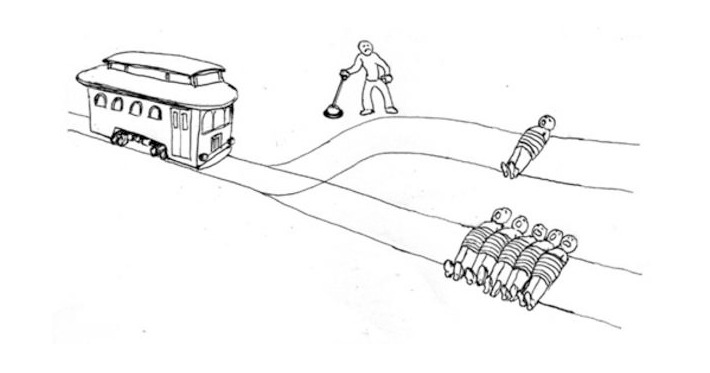

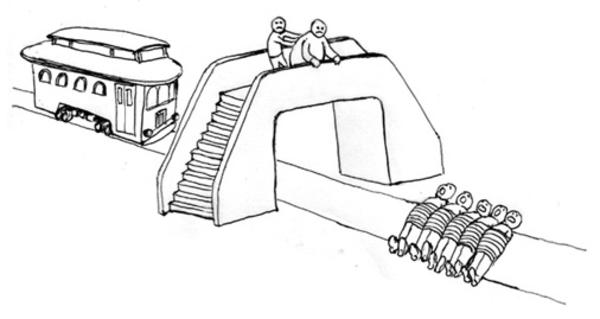

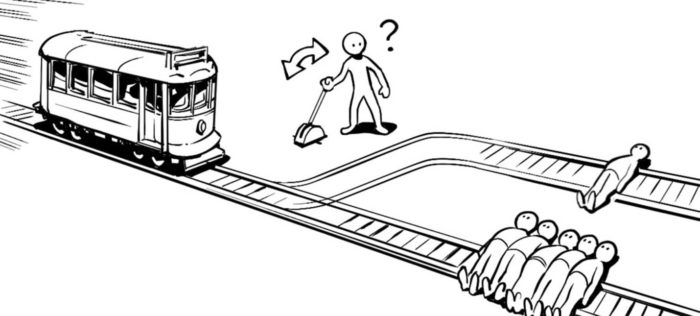

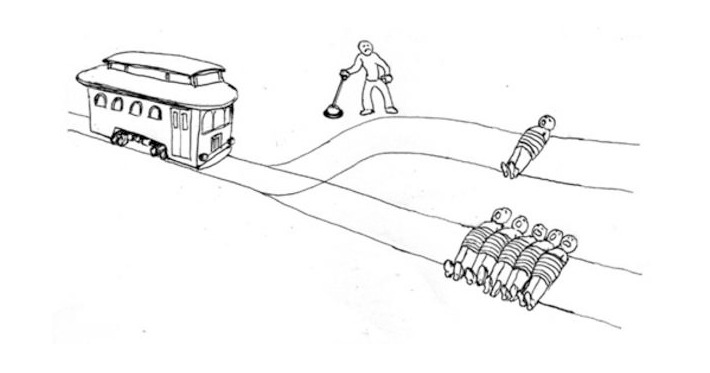

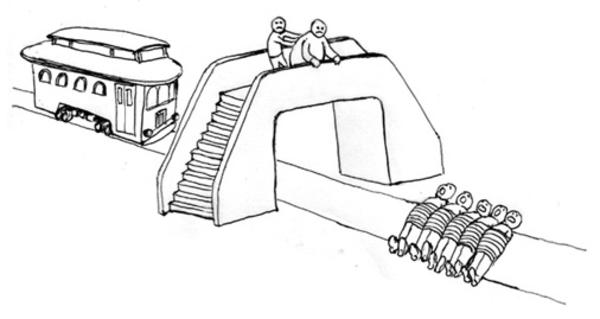

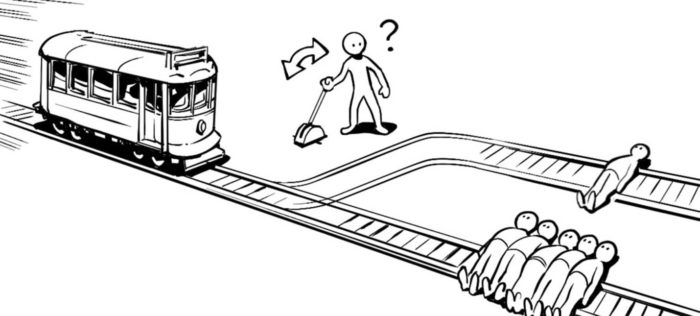

I’ve written about the “trolley problem” before. To briefly explain it for those unfamiliar with the concept, the trolley problem is an ethical thought exercise. The participant is faced with a series of dilemmas of escalating severity, the outcomes of which can be determined by whether or not the participant throws a hypothetical switch.

For instance, a train is barrelling down the tracks toward a man. If you throw the switch, the train will follow a different track, avoiding him. It would be tremendously difficult to argue, in that instance, that it isn’t ethically correct to throw the switch.

But then we have the train barreling toward two men, and if you throw the switch it will follow a different track and hit one man. That’s ethically muddier. Yes, you’d save two people instead of one, but that one will only die because you interfered. He’s safe unless you throw the switch. Which is ethically correct? Would your answer be different if it were five people in the train’s path and one that would be hit if you threw the switch?

The dilemmas take many forms from there, ultimately asking the participant to decide whether or not to intervene in any number of hypothetical situations. There’s no right or wrong answer; it’s simply a way for us and for sociologists to gauge our moral compasses.

When I wrote that article I linked to above, in January 2016, I referred to this as the Moral Sense Test, because that’s what I knew it as. (And, at least then, what it was actually called.) In the few short years since, the trolley problem has bled into the common language of popular culture, fueling a winkingly absurd meme page, an episode of Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, and a card game by the Cyanide & Happiness guys, to name just a few examples.

I think it’s notable that the trolley problem has so rapidly found widespread resonance. After all, it is at is core an exercise in which we are faced with exclusively undesirable outcomes and are asked, in essence, to chose the least-bad one. That’s something the entire world has been doing, over and over again, since 2016. It’s become a part of life, and our entertainment reflects that.

But video games, well before there was ever a term for it, have been conducting (ha ha) trolley problems almost as long as they’ve been around. In fact, you face one pretty much any time a game gives you an actual choice.

In 1987’s Maniac Mansion, for instance, the evil Meteor (an extraterrestrial hunk of sentient rock turning the Edison family into murderous monsters) wreaking havoc in the basement of the Edison Mansion can be dealt with in a number of ways, and you get to decide which is most fitting. You can call the Meteor Police to arrest it. You can stick it in the trunk of an Edsel that you then blast into space. You can get it a book deal. (Maniac Mansion is weird.) If I’m remembering correctly, you can also simply destroy it. The fact that I can’t be sure of that lets you know, ethically, the kinds of choices I gravitated toward, but that’s neither here nor there.

The point is that each of these outcomes have potential pros and cons, if you’d like to think beyond the strict narrative boundaries of the game. The Meteor Police can take it into custody, but what if it breaks out? You can shoot it into space, but what if it lands somewhere that it can do even more damage? You can get it a book deal and give it something productive to spend its life doing, but does it deserve a happy ending — and profit — after ruining so many lives?

For another high-profile example, jump ahead 10 years to the game that kicked off my favorite series of trolley problems: Fallout. Your home of Vault 13 needs a part to repair its water purification system; without it, everyone in that shelter will die. You find the part you need in the town of Necropolis…where it’s in use by another community. Swap out the nouns and you’ve got an actual trolley problem. Do you throw this switch to save one group of people while damning another? Do you have that right? Can you rationalize it ethically?

You can, in fact, resolve this issue without damning either community. (At least, without directly damning either community.) Through a more difficult series of events, and a reliance on a skill your character may not even have, you can fix the Necropolis water system so that it will run without the part you need to take home. Time is of the essence, though; take too long to figure out how to do this — and risk not being able to do it anyway — and the residents of Vault 13 will die. That’s its own sort of trolley sub-problem: Is it ethical to risk lives you could save right now in the hopes that you might be able to save more later?

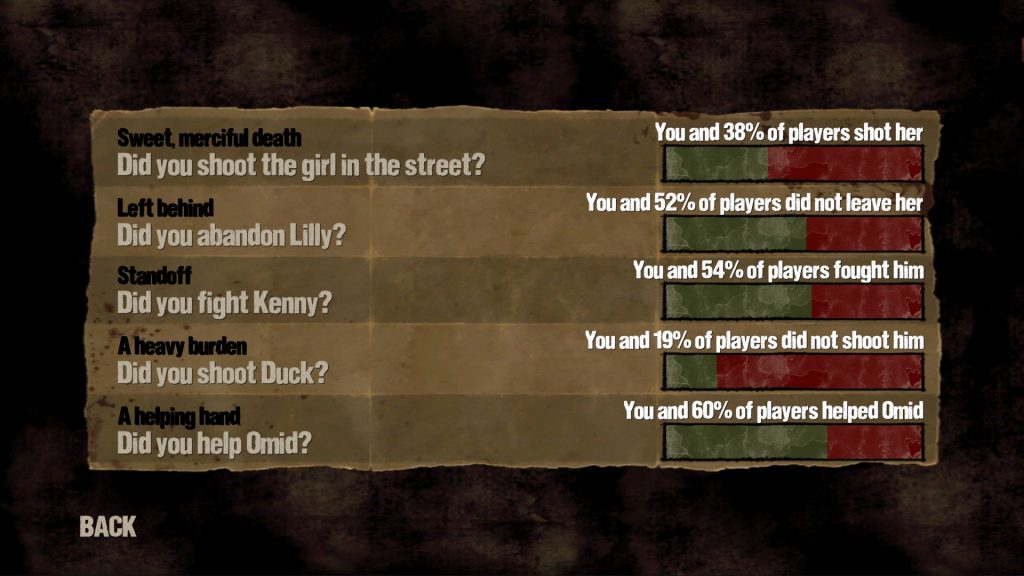

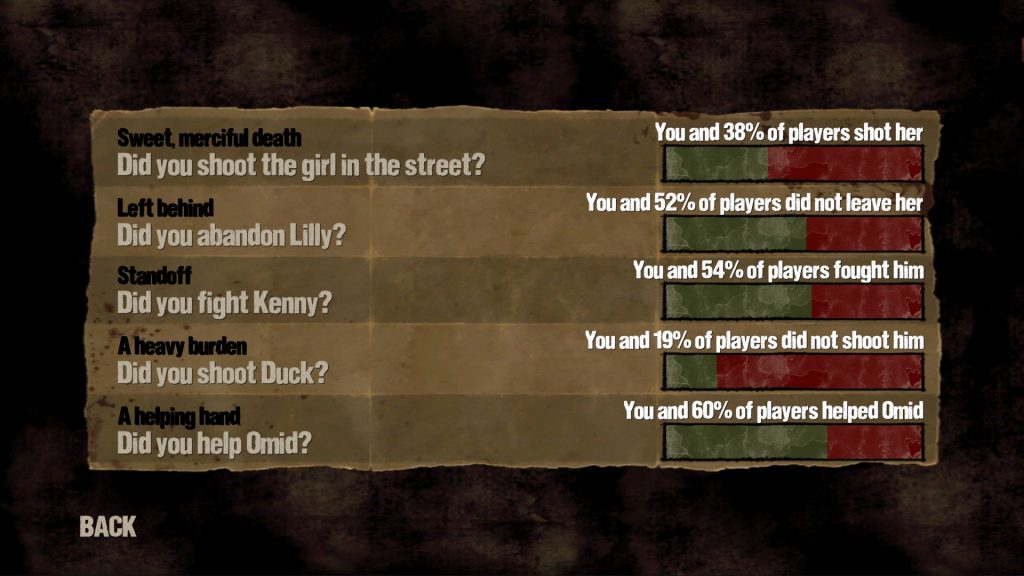

Jump ahead again to 2012’s The Walking Dead, 2015’s Life is Strange, and games along those lines, packed to the brim with trolley problems that often wear clever disguises, and which — much more in line with a formalized Moral Sense Test — process and analyze the numbers, letting you know what percentage of players made the same choices you did. You get to see how your personal morality measures up against a larger social average. (Presumably the developers of these games closely study the dilemmas that approach a 50%-50% split, in order to keep future choices just as tricky.)

Here’s the thing about the trolley problem, though: You’re making a decision consciously.

…well, yes, of course. Does that matter?

In a way, no. In a formal, Moral Sense Test-like environment, we are being asked to think. To ponder. To make a difficult decision that requires personal rationalization. Ultimately, we provide an answer. It may be one we’re unhappy with, neither outcome feeling personally, ethically correct. But that’s okay. Groups of people get studied through the years and sociologists track tends to come to some larger understanding of what is ethical.

In another way, yes, it absolutely matters, and it matters crucially. Because what we can get out of trolley problems ourselves is distinct from what a researcher studying data would get. To the researcher, those final decisions (along with, possibly, how long it took us to reach them) are important, but that’s it. We collect our $5 check and leave the office and they crunch data. The study goes on without us; the part we play in it has concluded and our specific answers will be smoothed out by averages.

But we, the individuals responding to any given trolley problem, can learn a little bit more about who we actually are. It’s a bit like that vegan billboard with a row of animals and the question “Where do you draw the line?” You’re supposed to think about it. Thinking is the point. Your decision — even in thought exercises such as these — is important, but it’s the thinking, the rationalization, the responsibility of accounting — inwardly — for what we would or would not do in a certain situation that matters.

That’s valuable knowledge. But because we know we’re making a decision — and an imaginary one without external consequences at that — it’s essentially bunk.

The decisions we make when faced with dilemmas on paper, in a formalized setting, in a multiple-choice questionnaire…they aren’t real. They reflect what we think we would do rather than what we would actually do. Because…well…they have to. We don’t know what we would actually do until we’re really in that situation.

In a general sense, we can see this in the number of films and television shows that pass focus group muster (or are altered to meet the feedback received) and flop massively. The participants in these focus groups are almost certainly honest — they stand to gain nothing from dishonesty — but the kind of project they think they’d enjoy isn’t the kind they actually end up wanting to see.

Or, as The Simpsons concluded after showing us focus-group absurdity in action, “So you want a realistic down-to-earth show that’s completely off the wall and swarming with magic robots?”

In a less-general sense, I worked at a university a few years ago, and we had a mandatory active-shooter drill. It was unpleasant, as you’d expect, but what will always stick with me is that during the debrief, as folks discussed exit routes and hiding places and the best ways to barricade specific doors, some of the younger members of staff made comments — under their breath sometimes, slightly over the rest of the time — about how they’d just run at the shooter and tackle him, try fighting, at least go down swinging…you get the picture. They mumbled and interjected, and that sucks, but at the same time, I get it.

A woman I love and respect dearly who is, I think, three or four years older than me, was evidently very displeased with their comments. She spoke up finally. She said, firmly, “You haven’t been in an active-shooter situation. I have. Everybody thinks they’re going to fight. They don’t. Everybody thinks they’re going to be the hero. They aren’t. When somebody comes to work with a gun and starts shooting at you, the last thing you’ll be wondering is how to get closer to them.”

I’m paraphrasing, necessarily. It was a sobering moment. She shared more details that aren’t necessary, suffice it to say both that a) hiding doesn’t indicate cowardice and b) the 250-ish mass shootings in America so far this year prove her right. You can count the number of people who tackled a gunman on one hand. Everything else is either resolved by the police or the gunman himself.

It’s a long way around, but in that debriefing, we were faced with a trolley problem, and the group of younger males gave their hypothetical answers. They weren’t lying. They were honest. That is what they assumed they’d really do. But my friend spoke up with the cold reality that in the moment, under pressure, unexpectedly having to respond, without time to think or plan or weigh options, they’d do something very different.

So while trolley problems — literal and figurative — are a great way to get people to think about right and wrong, ethical and unethical, where they’d draw the line…they are a terrible way of gauging how somebody would actually behave in the same situation. Both points of data are important, but we can only measure one in a controlled environment.

In the Moral Sense Test. In a debriefing. In a video game.

Controlled environments.

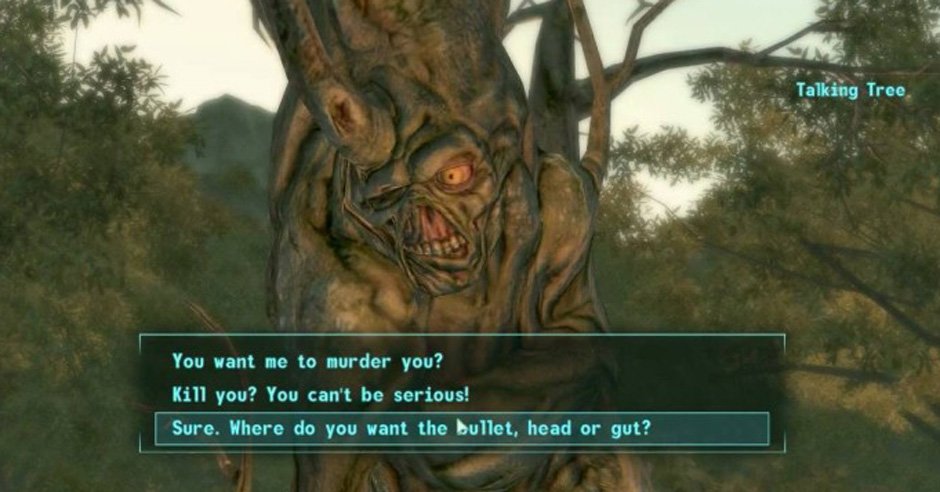

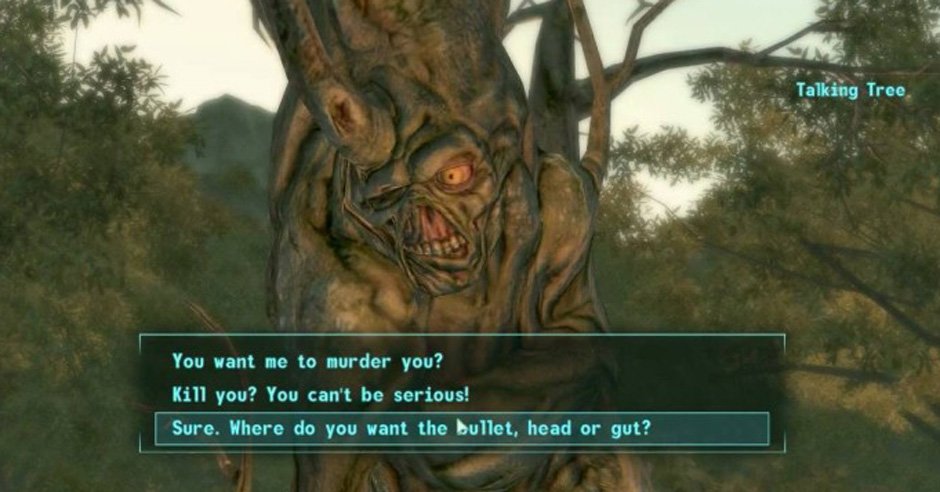

And so when you need to decide in The Walking Dead which of the starving members of your group get to eat that day and which have to go hungry, you know you — you playing the game — have the dual luxuries of time and distance. When tree-man Harold in Fallout 3 asks you to euthanize him, though keeping him alive against his wishes means foliage and wildlife returning to the Wasteland, you can think ahead. You can act pragmatically. You can understand that whatever happens, these are characters in a game and while you may not be happy with the outcomes of your choices, you won’t really have to live with them.

Enter 2017’s Prey. Initially I had intended to write this article focusing on Prey alone and praising it for being the best execution of the trolley problem I’ve ever seen.

Consider this your second — and final — spoiler warning if you ignored the one that opened this article.

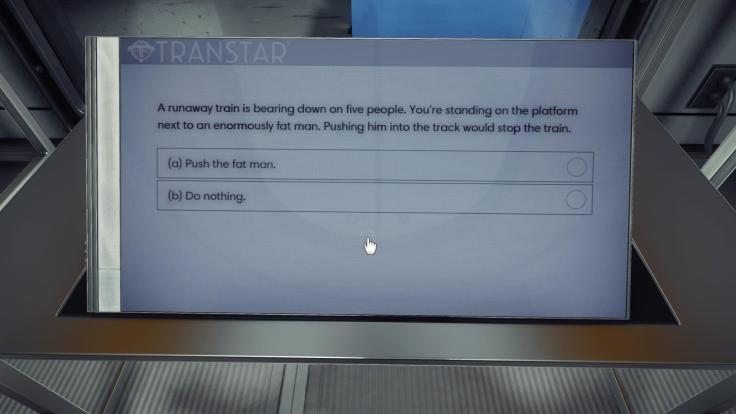

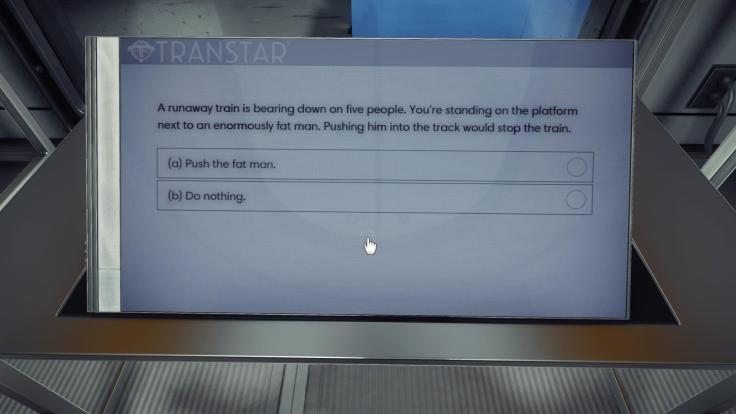

Prey begins with a trolley problem. A real one. Several real ones, actually. Your character is run through a series of tests, including multiple-choice questions. Some of them are classic trolley problems, plucked right from the Moral Sense Test.

And that’s it. It doesn’t quite matter what you pick, because you don’t know the purpose of the test (yet) and, just like trolley problem exercises in our world, there are no consequences for your decision.

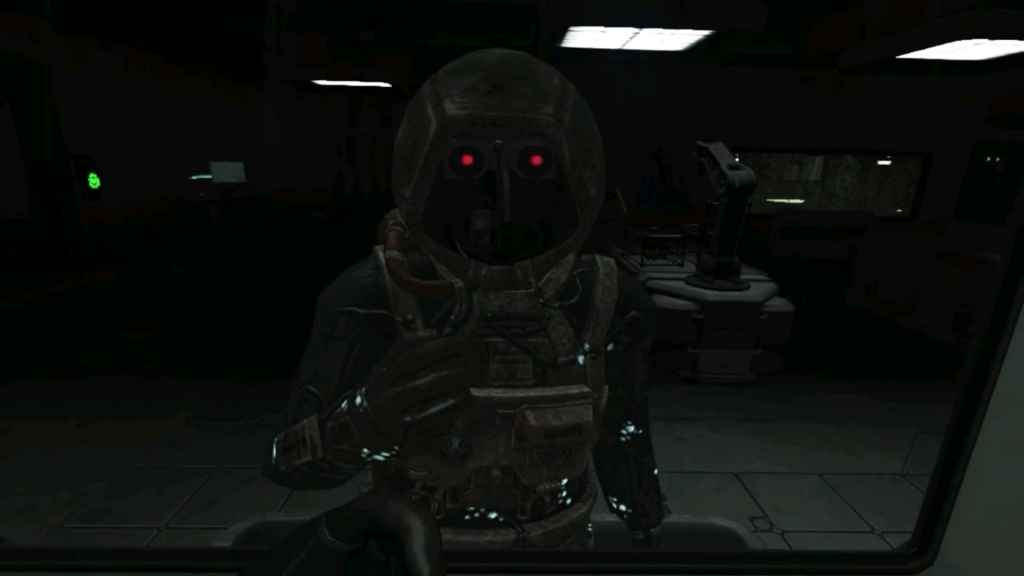

What we learn, gradually throughout the game, is that this isn’t our first time taking these tests. We are aboard a massive research station in outer space. We have developed neuromods (basically sets of knowledge, skills, and talents you can plug into your brain) using alien DNA. The neuromods are not able to be swapped in and out safely, at least without massive memory loss, but your character, Morgan, volunteers to be a test subject to change that.

So every day you’ve been taking the same tests, your memory wiped clean from installing and removing a neuromod. The scientists administering the tests are tracking your responses to see if there is a kind of memory left behind. Will your answers be the same each day? Will you arrive at them more quickly, because you have seen them before, even if you don’t remember them?

Well, we never find out because Prey is a horror game and the aliens bust out of containment and slaughter almost everybody aboard the space station.

You then wake up in your bed, as though from a nightmare…but the nightmare is real. It’s your bed — like your entire apartment — that’s a simulation. In order to avoid the panic that would come with waking up in surroundings that are in anyway unfamiliar (remember, your character doesn’t remember she’s repeating the same day and over), the researchers have set up a small number of rooms to simulate the same events in exactly the same way every day. Also, y’know, they want to make sure deviations can’t affect the data they’re collecting. Morgan is in a controlled environment.

One of the game’s great moments comes soon after the test, when you wake up in your room and you can’t leave. Something has gone wrong. You’re trapped until you smash the window overlooking the skyline in your high-rise apartment and find…that you’re actually on a sound stage.

It’s a good mind-fuck moment, but smashing that window also smashes the barrier between the two halves of the trolley problem’s data. Instead of simply answering questions on a touchscreen, Morgan is now going to find out what she would do in reality.

For most of Prey, you don’t encounter other survivors. You discover their corpses. Your friends and colleagues are torn to bits, smeared across walls and floors, in some cases braindead zombies controlled by the aliens running amok. As one might expect from a game such as this, you can find their audio logs and read their emails and dig old notes out of the trash cans to learn about who each of these people were.

Because they were people. They’re chunks of bloodied meat now, but they were people. You get to learn who they were and what they were doing. The first time you find a body, it’s scary and gross. As you learn about them and the lives your careless research has ended, it becomes sad. And then, of course, you get used to it. You’ve seen enough dead bodies — whatever number that is — that you are numb to them.

Which is why when you finally do encounter a survivor, it matters. In most games, meeting an NPC means you’ll get some dialogue or a mission or an option to buy things. Here it jolts you back to reality, because you have evidence that you aren’t alone, that someone else has lived through this nightmare, that with a friend by your side it becomes that much easier to figure out how the fuck to get out of this mess.

At least, that was my experience. Yours might have been different. After all, survivors have needs. They have requests. They can slow you down. And as the space station is gradually taken over by the aliens — something you witness unfold during the game, with hostiles encroaching as time passes into previously safe areas — you might well have decided to focus on yourself, your own survival, the much-more-pressing matter that’s larger than the safety of a colleague could ever be.

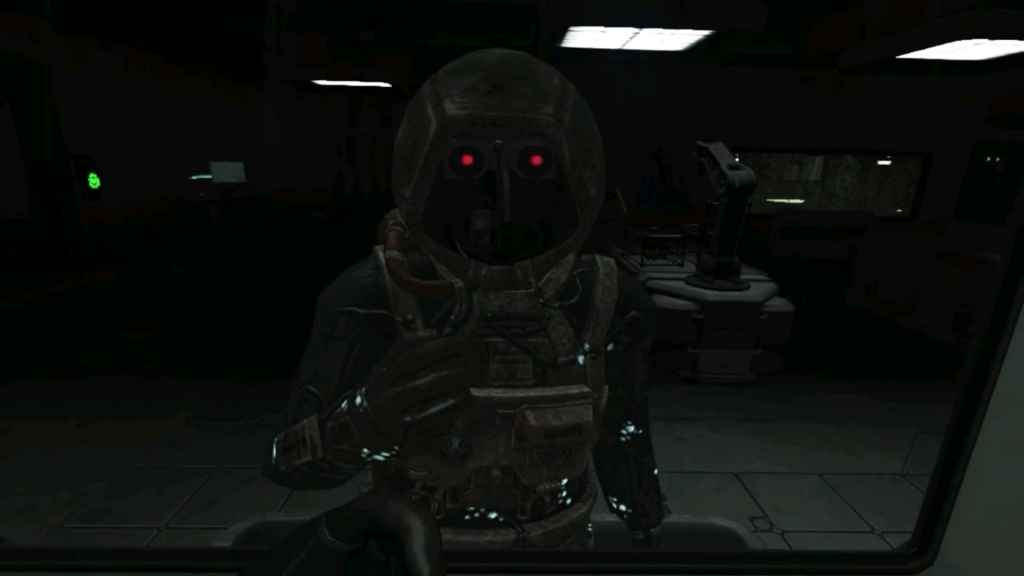

And at the end of the game, whatever decisions you made, however you handled the alien menace, whether or not you put your own needs above others’, you learn that you aren’t Morgan at all. You are a captured alien. You had Morgan’s memories implanted into you — like a neuromod — and were run through a simulation of the disaster that really did happen on the space station.

Why? Because whatever the real Morgan and others attempted was unsuccessful. The alien infestation has spread to Earth, and while humanity still exists it has decisively lost the battle. Throughout the game you searched for ways to beat back the invasion, without having any idea that it was already too late to win.

Humanity’s only hope is to broker a peace with the aliens. They won’t leave Earth, but perhaps they can achieve a kind of truce that would allow mankind, at least, to survive. By running you through that simulation and seeing how you responded to various things, the researchers are in a better position to decide whether or not you — this one particular alien — can feel enough empathy toward humanity to broker that truce.

In summary, it was a trolley problem. And the researchers in this case understood that hypothetical situations might not correlate to reliable data, and that can be a problem, especially now when they might not ever get another chance at success. They had to be certain, and for that reason they didn’t give the alien any formal version of the Moral Sense Test; they plunged him into a simulation without his knowledge or consent, because that was the only way they could be certain his responses to stimuli would be genuine.

They could have — if they really wanted to — found some way to ask him the same questions, giving him time to reflect, giving him the luxury of rational thought. But the only way they’d know for sure is to watch him make or not make those same decisions.

Is it worth attempting to rescue a survivor drifting in space, or does the fact that he’s minutes from death make him a lost cause? Do you put yourself in danger to retrieve necessary medication for another survivor, or do you leave her behind? (Complicating this one is the fact that she expressly tells you not to go back for it; she understands that she’s going to die and that it isn’t your problem.) Do you find some way to neutralize the alien threat? Do you contain it so that the neuromod research can continue? Do you say “fuck it” and just jet back to Earth leaving the space station to its fate?

The core “it was all a dream” reveal earned Prey some backlash, but not as much as I would have expected. The game was strong enough and well-enough written that many critics and fans gave it the benefit of the doubt and were willing to believe that the ending justified itself, whether or not they understood the reason for it.

Those who were critical of it argued that your decisions didn’t really matter, because you were making them in a simulation, and once that simulation was over you weren’t even in the same world anymore. But I’d argue that that’s exactly why they mattered. Before the reveal, you thought this was reality, and acted accordingly. Had you known it was a simulation, you might as well have been answering a series of yes or no questions.

The reveal means that at the end of the simulation, the researchers have a strong understanding of this alien’s particular sense of personal ethics…as well as the value (or lack thereof) of human life.

What Prey does beautifully, though, is encourage conversation beyond the boundaries of its own design. The alien saw through Morgan’s eyes. You see through the alien’s eyes seeing through Morgan’s eyes. The alien is, ultimately, playing what is essentially a video game, which is also what you’re doing. It’s a Russian nesting doll…a simulation within a simulation (and containing other, smaller simulations). You have a level of “belief” in the world that you wouldn’t have had if you’d known it was a simulation at the outset.

Games are always testing you, whether or not they do anything with the results. Prey just has the guts to let you know it. When the adventure aboard the space station is over, the alien is sitting upright in his chair, in a room far from anything he’s just experienced. You, likewise, are sitting in yours, in your own room, far from anything you’ve just experienced. The alien is directly and explicitly judged for his actions by the researchers.

Which…were your actions. They call him out for those he abandoned, those he failed to save, those he couldn’t save, and praise him for making decisions that helped others, to whatever small degree, even in the face of looming human extinction. The first-person view employed by the game means the researchers are also speaking to you, judging you precisely as much for precisely the same reasons.

Like the alien, you don’t get to answer some trolley problems and walk away, leaving the researchers to their data. You’re there, being lectured, accounting for the decisions you’ve made and the action you’ve taken or failed to take. You’re being told exactly how reliable you would have been in the face of catastrophe.

And it’s remarkable. It makes you think about what you’ve done in a way that has nothing to do with in-game rewards. The reward — or punishment — is inward, because in this moment of forced reflection you have to come directly to terms with who you’ve proven yourself to be. Were you a good person who tried their hardest? Were you a selfish ass? Probably you were somewhere in between, so were you closer to either end? Where do you draw the line?

In the first draft of this article that I never wrote, I was going to argue that Prey was gaming’s best trolley problem, because it both adheres to and undercuts our expectations of one, and it measures how we’d respond to a formal test and how we’d respond to an informal disaster. It asks us where we’d draw the line, and then it tests us, and forces us to account for drawing it any differently.

When I chose to end Harold’s life in Fallout 3, that was it. I felt his wishes were important, and keeping him alive against his will seemed cruel. If The Wasteland were going to be restored, it would have to find a way to do it without keeping an innocent man in a state of permanent agony. But then I moved on, and I did some other quests, and while I never quite forgot about Harold, I never had to account for what I did. As suggested by the dialogue options you see here, I was essentially answering a multiple-choice question, and afterward I could walk away.

In Prey, my decisions literally defined me, and they made me realize that they could define me in any other game as well. The only thing missing from other games is a panel of researchers materializing at the end to call me a standup guy or a piece of shit. But now that I’ve been judged for it once, unexpectedly, it’s redefined games in general for me.

They are simulations. Whether or not a researcher learns what I do, I can learn what I am.

Then, months later, I played Soma, and it may have outdone Prey with its own trolley problems, this time without ever drawing attention to the theme.

And that, I think, is important. It’s one thing to make a decision on paper. It’s another to know — or believe — you are making a decision in reality. It’s a third thing, and perhaps the most telling, to not know you’re making a decision at all.

In this third case, conscious thought doesn’t even enter into it. And when you make an ethical decision, you get a far better sense of who you are when you’re on autopilot. When you’re not thinking. When you aren’t even aware of what you’re doing.

In Soma, we play as Simon, a man suffering from a brain injury. Early in the game we visit his doctor, who attempts an experimental treatment (with Simon’s consent, I should add). He captures a digital model of Simon’s brain, and plans to run it through a variety of simulated treatments while Simon himself goes about his life. The idea is that eventually the simulation will hit upon a treatment that works, and then that treatment can be explored and potentially performed on the real Simon.

Fine, right?

Well, as Simon, you sit down in the doctor’s chair, the doctor starts working his equipment to capture the digital model of your brain, and in the blink of an eye you’re somewhere else entirely.

At first you don’t — and can’t — know where you are. The doctor’s office is replaced by cold steel and sparking electricity. You’re in an environment more advanced than the one you left, but also one that is clearly falling apart and long past its prime. Robots of various kinds roam the halls. Some seem to be afraid of you; others are clearly aggressive. You’ll probably ask yourself what the fuck is going on.

…and then you’ll probably know the answer. This is the simulation Simon’s brain is undergoing. Before the process began, we and Simon — and probably the doctor — figured a digital model of a brain was nothing more than 1s and 0s that could be reset millions of times over for the sake of simulating the results a near-infinite amount of stimuli and potential treatments would have on the real brain.

In fact, our outlook is given away by our word choices. “The real brain.” “The real Simon.” Everything else is just…data.

Until we wake up in this spooky, damaged environment that’s barely hanging together, infested by robotic creatures doing it further harm and attacking…well, us. Our consciousness.

This is how Simon’s brain — digital though it is — processes its situation. It doesn’t know it’s experiencing a simulation, so it assigns shadowy shapes to the dangers and represents its own neural pathways as a series of long, winding corridors, some of which are already damaged beyond repair. As the doctor bombards Simon’s brain with various potential treatments, the brain incorporates these new feelings — pleasure, pain, anxiety, hopelessness, fear — as additional aspects of the world it’s mentally constructed. New enemies appear, friendly faces introduce themselves, potential ways through and out of this ringing metal hellscape come together or fall apart…

It’s a clever and interesting way to observe the treatment as it happens from within the simulation, not just seeing but experiencing the ways in which the human mind strains to apply logic to that which it cannot understand.

…only, y’know, it’s not that. That was your brain trying to apply logic to what it couldn’t understand.

One of Soma‘s best twists is the fact that the situation in which Simon finds himself isn’t a twist. He is exactly where he seems to be.

He was in a doctor’s office one moment, and the next he was in this underwater research facility, isolated at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. The more he explores and learns, the more we understand. Earth was struck by a meteor that wiped out life as we knew it. The researchers at the bottom of the sea survived the mass-extinction event, but obviously that would only be temporary. Humanity was doomed, and there wasn’t anything the few survivors at the bottom of the ocean were able to do about it. Simon’s nightmare turns out to be real.

And once you know what’s happening, the question instead becomes, “How did I get here?” After all, what does Simon have to do with any of this?

The answer is actually pretty simple: Nothing. Simon has nothing to do with any of this. So why is he here?

The answer comes later in the game, but I think it’s possible to overlook it if you’re not being thorough. You’ll find some recordings of the doctor who performed the experimental procedure on you. In one, he’s talking to Simon. To you. Only it’s something you haven’t heard before. It’s a recording made some time after you sat down in that chair and had your brain mapped.

The doctor tells you that the experiment has failed. None of the treatments seemed to work. He would not be able to help Simon recover from his brain injury.

However, the digital model of Simon’s brain could still potentially help others. It’s valuable data. It’s a major step forward in mankind’s potential understanding of neurology. He asks Simon for permission to keep using it, to keep experimenting on it, to share his findings and research with the greater scientific community.

Simon doesn’t hesitate. He says of course, please use it. He understands that he can’t be helped, but sees no reason whatsoever the digital model of his brain shouldn’t be used to help others.

You can possibly guess what happened at this point, but let’s step away from Soma for a moment.

I’ve thought about things like this before, and I’d have no problem with allowing the doctor to continue his research on my digital brain if I were in Simon’s situation. I know this, without question, because there is no reason not to. I would stand to gain nothing by refusing, and I’d be robbing society of potential enrichment.

The first time I was given reason to consider these things was when I read The Emperor’s New Mind, a non-fiction book exploring an intersection of mathematics and philosophy, with an eye toward artificial intelligence. Specifically, it was an early stretch of the book about teleportation.

It’s been years since I’ve read it, so I can’t quite remember why author Roger Penrose spent several pages discussing the established sci-fi concept of teleportation. Indeed, he’s specifically focusing on the fictional portrayals that we see in things such as The Fly and Star Trek, wherein a human being stands in one place and some futuristic device removes him from that place and places him at his destination.

Penrose argued that such a thing wouldn’t quite be teleportation. Instead, the man standing in one place would be destroyed by the process, and a second man — though identical — would come into existence at the destination. You aren’t teleported, in other words; you cease to exist and another version of you is brought into existence elsewhere. (This theory was even discussed in an episode of Breaking Bad.)

I didn’t quite buy it, which I remember thinking was okay. I didn’t get the sense Penrose was trying to convince me he was right; I think he was more encouraging me to think about things that I wouldn’t have thought about otherwise. I was a philosophy minor, which means I’m pretty comfortable with the thought process being more important and often more valuable then wherever you land at the end of it.

At the very least, I figured the distinction was academic. If Scotty beamed Kirk up, did it matter whether it was a single, smooth process or a destructive/reconstructive one? If the end result was the same — Kirk was there and now he is here, no worse for the wear — did it matter?

No. It didn’t. Easy.

Much later a friend shared with me the concept of Roko’s basilisk. I’m far from the person to explain it accurately, so please do correct me in the comments, but I’ll do my best to offer what I retained as the summary.

Roko’s basilisk is a hypothetical AI that could exist in the future. It’s advanced and capable of independent thought to degrees that we couldn’t possibly hope to create today. However, the reason we can’t create it today is that, y’know, we aren’t trying. We aren’t actively working to create it. We’re doing other things that gradually push the research forward, and we’ll eventually get there, but we’re not there today, weren’t there yesterday, and won’t be there tomorrow.

This pisses Roko’s basilisk off so much that when it does exist, it exacts revenge — in digital form — on everyone who didn’t actively help bring it about sooner. It tortures and torments simulated reconstructions of them for all eternity.

This is a scary concept, for some. “He’s basically God, but at the end of the universe instead of the beginning,” my friend said, and he definitely wasn’t referring to a loving or forgiving God. This was the Old Testament bloodthirsty God.

It’s not scary to me. It wasn’t and isn’t. Because a simulation of me isn’t me. I’ll die at some point. If a simulation of me lives on, who cares? If it’s tormented, who cares? If it’s treated like simulated royalty, who cares? It isn’t me, and I’m not here anymore.

The threat of Roko’s basilisk relies on a belief that a simulation of me is me.

But it’s not. So there.

Teleporters and basilisks. If it’s a copy, it isn’t you. If it’s you, it isn’t a copy. This is easy stuff, people.

So back to Soma.

Doomed at the bottom of the sea, one of the researchers has an idea. She comes up with a ray of hope, or the closest thing to a ray of hope the last straggling survivors of the apocalypse could have.

She proposes the construction of what she calls an “ark.” It’s basically just a computer, and the survivors can digitize and install their consciousness to it. Then she’ll blast it into space and…that’s it. They’ll still die, here, alone, without any hope of rescue, at the bottom of the ocean. But in theory, at least, mankind will live on. It’s just 1s and 0s representing people who are no longer alive, but it’s something, right?

In the game, we learn all of this in the form of gradual backstory. The ark project has already happened. It’s never presented to us as a “solution” to the problem. Instead, it’s something constructive the researchers can do, a project they can work on rather than wait around to die.

Another researcher, though, seems to subscribe to Penrose’s belief. Copying one’s consciousness to the ark wouldn’t really copy you over, because the two versions of you would deviate from each other far too quickly. One of you is on the ark, and the other is at the bottom of the sea, doing things, living his life, going about his final days, drifting further and further from who he was when his consciousness was copied to the ark. Before long — before any time at all, really — it wouldn’t be you on that ark anymore. It would be something — or somebody — based on what you were at some point. That’s distinct from “you.” It would be somebody else.

So this researcher shares his views with some others. He calls it Continuity, and he convinces others of it as well. It requires the survivors to commit suicide as soon as they upload their consciousness to the ark. That’s Penrose’s teleportation. The version of you on the ark would be you, because you existed here and now you’re there. There would be no deviation (aside from the necessary one: one of you committed suicide), and you would actually get to live on in a digital form.

It’s madness, of course. It’s idiotic and false, but it catches on, and a number of researchers do kill themselves right after the upload, all in service of Continuity. Which is complete bullshit. Because they exist. The “real” versions of them are destroying themselves and the false, lesser, artificial copies are being preserved.

I know exactly where I stand. The Continuity. Penrose’s teleportation. Roko’s basilisk.

I understand what everyone’s getting at. I see their points. I follow their arguments. And I disagree.

But what of Simon?

Simon, we learn, isn’t Simon. At the beginning of the game, Simon is Simon. When we find ourselves in the sealab, though, “Simon” is a robot with Simon’s memories loaded into it. That’s why we popped right from the doctor’s office into the research station; that’s when the mind-mapping happened. Whatever Simon did after that, “Simon” doesn’t have access to. Between the space of two seconds, he stopped existing there and started existing here.

His consciousness is loaded onto this robot because the doctor spread his research far and wide. He made it available — again, with Simon’s consent — for others to use, to study, and, in this undersea laboratory, to employ. As we wandered the research station and fought to survive, we thought we were controlling Simon, but we were controlling a robot who thought he was Simon. Oops.

At some point, “Simon” has to explore the depths of the ocean outside of the lab. The pressure would crush his robot body, though, so with the help of another AI he decides to load his consciousness — Simon’s consciousness — into a different, sturdier body.

Why not? He’s just a robot, right? What difference does it make which body he uses?

So you sit down in a chair like you did at the beginning of the game and in the space between two seconds your consciousness is copied from one body into another. You open your eyes in your new, sturdier frame and…you hear yourself asking, from the chair you initially sat down in, why the transfer didn’t work.

Because that version of Simon kept existing. It sat in the chair and…stayed there. Nothing happened, from his perspective. But from your perspective, everything happened. You popped into existence elsewhere, in another form. The Simon in the chair panics and passes out.

That’s it. You need to explore those depths. That’s your next task. You aren’t making a moral or ethical choice. Soma is linear and you follow a set of objectives in a predetermined sequence.

But when this happened, I didn’t leave the research station the way I should have. That was my goal, that’s what I had been working toward, and now I could do it. But I didn’t do it.

Instead I walked over to the Simon in the chair and shut him down.

Because if I left him there, he’d wake up. And he’d be trapped. Because he can’t go any farther and his body can’t withstand the pressure. He’d be left alone with the scary monsters at the bottom of the sea with no hope of rescue. So I shut him down. I killed him.

Because he wasn’t a robot.

Or, he was. Obviously he was. But wasn’t he also Simon? Wasn’t he me?

He was. I controlled him. The game said I was Simon, and I controlled Simon. Later I learned it was a robot with Simon’s consciousness, and fine…it’s sci-fi. Life goes on.

But then when I transferred to another body, and that Simon stayed alive…panicking, asking why the transfer didn’t work, fretting, knowing he was trapped…I suddenly saw him as more than just a robot with Simon’s consciousness. He was me. I really would be leaving “me” behind. I really would be subjecting “me” to an eternity of hopeless torment. That robot could survive without any hope of escape for years, decades, centuries. Trapped and distraught and miserable. And I couldn’t let that happen.

So I didn’t let that happen.

And the best thing about how Soma handles this trolley problem is that it doesn’t present it as one. I’m not being faced with a moral dilemma. I’m not being told that my ethics are being measured. In fact, they aren’t.

A number of situations like this occur throughout Soma, and at no point do your decisions have in-game consequences. If you spare someone’s life, they won’t come back and help you later. If you choose option A, you don’t get a better weapon. If you choose option B, you don’t get a better ending. If you choose option C, you don’t open up new and interesting dialogue choices.

Soma is designed so that it doesn’t matter, to the game, what you do. It is, after all, a dead-end situation. Humanity is doomed. You’re a robot investigating a sea of corpses. Do the right thing, do the wrong thing, it doesn’t matter. It’s already over. The game doesn’t care, and the tasks unfold the same way however polite or rude you are while doing them.

And that’s fantastic. Because it means the consequences are within you. The game doesn’t judge you; you judge yourself.

And because it doesn’t judge you, and doesn’t even pretend to judge you, the data you can gather about your own moral compass is far more reliable.

Soma didn’t present me with a moral choice regarding shutting Simon down. I could do it or not; it wasn’t the task at hand. But the mere fact that I saw it — immediately and urgently saw it — as an act of mercy is remarkable.

Had I been asked if a simulation of me were me, I’d have said no. In fact, I had said no every time I encountered the prospect in the past. Put my hand on that lever and present me with the trolley problem, because I know my answer.

But Soma doesn’t structure it as a trolley problem. I think it “knows” that players will question things like Continuity and the simulated treatments for Simon’s brain damage and many other things and arrive at their own conclusions. I’m pretty sure most of them would have arrived at the same one I did: a copy of something isn’t that thing.

And Soma is fine with that.

But then it puts us in a situation that gives us a chance to prove our beliefs. It’s just something that happens. We don’t have to pay attention to it, but we will.

Because when we can sit back and rationalize something in a hypothetical sense, we’ll come to a conclusion. In reality, faced with the actual situation, without the luxury of theory and cold logic to separate us from what’s really happening right now, we could well come to a different conclusion.

Soma raised a question I’d already answered many times before. That could still be interesting, but probably wouldn’t be meaningful. What gave it meaning was the fact that, for the first time ever, it got me to answer that question differently.

It reset my thoughts. It allowed me to think the problem through all over again, arrive at the same conclusion, and then proved me wrong. It showed me the flaws in my own reasoning not by providing a counter-argument, but simply by giving me the chance to practice what I preached.

And I didn’t

And I didn’t even realize I didn’t.

I wasn’t in that situation and thinking, “Actually, now I understand that simulations of me are me.” I was in that situation and I thought, “I can’t fucking do this to myself. I can’t leave myself here. I’d rather die than be left here.”

And I moved on with my life. I moved on through the game. I turned the game off and I got ready for bed. And somewhere, at some point, it clicked in my mind.

Because I wasn’t given a trolley problem. I just did something and later reflected on that decision and realized just how completely my actions flew in the face of what I thought I believed.

I understood myself a little better after that. Soma took both the trolley problem and the real-world application of the same problem, and let us see whether or not our actions supported our beliefs.

The game doesn’t know what my beliefs were before this moment. The game doesn’t care. Nor should it.

But I should sure as hell care.

Soma didn’t present me with a difficult moral quandary. At least, not directly. It just let me do whatever I did. And then later, inside, lying down, trying to fall asleep and failing to do so, I found myself evaluating my decisions and reevaluating things I thought I’d figured out long ago.

Trolley problems help us decide where we draw the line, but they tend to involve rationalizations after the fact. We decide what we’d do and then attempt to justify it, landing on some explanation that satisfies us, regardless of its degree of bullshit content.

This version of the problem asked me to draw the line, which I did. Then it pulled back the curtain to reveal that actually, when not drawing it consciously, I drew it somewhere very different.

That’s the best version of the trolley problem, I think. It’s not just a difficult one that provides useful data…it’s one that makes us realize how far from the truth our rationalizations actually are.

Video games are uniquely positioned to help us experience these awakenings, and so far I believe Soma has done it best. Games are simulations that immerse us in little worlds, and we do within them as we please. If a game can reveal the band of darkness between our beliefs and our methods, that’s uniquely valuable, and potentially revelatory.