xoxo Isaac

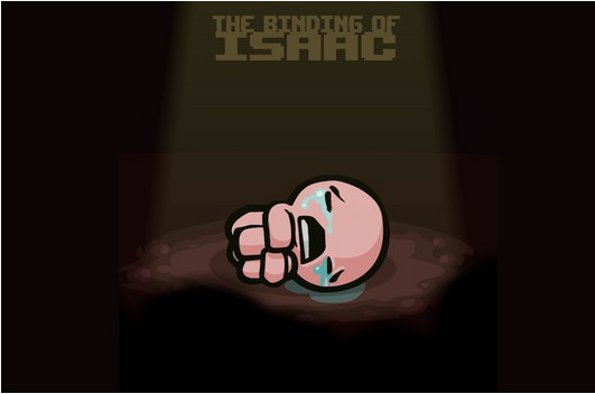

I had something else in mind for my second Noiseless Chatter Spotlight, but the fact that it’s getting pre-empted at the last minute is pretty appropriate considering its own pedigree, so I don’t have too much regret that I’m instead spotlighting a computer game from last year called The Binding of Isaac.

The Binding of Isaac has been the subject of some conversation today, as Team Meat, the game’s developers, have announced that Nintendo has declined to sell the game through its downloadable software services. That should come neither as a surprise nor as an announcement worthy of much discussion at all, and yet an awful lot of otherwise quiet people sure have a lot to say. NintendoLife’s news article on the announcement has over one hundred comments already, as of this writing, and it’s rare that anything but the most controversial news items get anywhere near that much discussion. And that’s not taking into account the forum post on the same topic that spans several pages.

But what’s controversial about Nintendo choosing to pass on hosting a game in its marketplace? Games — and developers — are declined all the time. Granted, we usually don’t hear about it, but there’s something unique here. There’s something about The Binding of Isaac that commenters, gamers, people feel the need to chime in about. It’s not a topic that can be allowed to pass without remark. This is a game that everybody has an opinion about, even those who haven’t played it, and believe me, brother, if somebody mentions the game in any context, you’re going to hear everyone else’s opinion, too.

The comments on the article linked above are fairly evenly split between “this game is art and Nintendo has no right to deny gamers access” and “this game is filth and Nintendo was right to decline.” My opinion is somewhere in the middle: this game is indeed art, and Nintendo was also right (or at least had a right) to decline.

There are three separate, but related, identities that we need to consider when we discuss this game: firstly, The Binding of Isaac as a piece of entertainment, followed by The Binding of Isaac as art, and finally The Binding of Isaac as a product.

We’ll start with looking at it as a piece of entertainment…or, even more simply, as a game.

We’ll start with looking at it as a piece of entertainment…or, even more simply, as a game.

The Binding of Isaac is a Flash-based game of survival and exploration, with a heavier emphasis on the former than the latter. Its obvious reference point is the original Legend of Zelda for the NES, which it references visually throughout the game, and from which it takes many of its gameplay features, such as the finding and using of items, the treasure boxes, and the periodic boss battles. It’s a love letter to that video game classic in the same way that Team Meat’s earlier Super Meat Boy paid homage to other such early masterworks as Super Mario Bros., Mega Man and Castlevania. Team Meat knows their medium’s history, and they are quite content to package affectionate — and lovingly monstrous — reactions and responses to them as new games.

While many gamers (and, indeed, people) see such grotesque subversion as a cheap method of getting attention for a game that might not otherwise have seen a large audience, the fact is that neither Super Meat Boy nor The Binding of Isaac stop there. While shock for shock’s sake is instantly wearisome, the over-the-top bloody nightmare of Super Meat Boy revealed itself to be a brilliant and well-designed journey through clever stages and creative boss encounters. And The Binding of Isaac transcends its scatological obsession with the grotesque and hideous to become a game about games, a game that isn’t so much about survival as it is about what it means to survive. It doesn’t just push boundaries…it questions deeply the experiences we have between the boundaries we already know. It raises questions we never thought to ask, and it answers them exceedingly well. It’s designed to look like The Legend of Zelda, but its intention is to remind you of other, very different, things from your childhood: trauma, confusion, loneliness, frustration, and that feeling we’ve all had at least once — and which we all can remember so vividly if we conjure up the memory again, or have it conjured up for us — that the world is a cruel place that never wanted us here to begin with.

As you can see, we’re already drifting into a discussion of The Binding of Isaac as art, so allow me to just get the following out of my system: many times I’ve seen people shrug and say something to the effect of, “Art is in the eye of the audience.” This is their way of saying that, hey, maybe they don’t understand something, but somebody else might, and to that hypothetical somebody else, it might be art. In other words, art is subjective. Not as an experience, but as a classification. That, my friends, is bunk.

I think it’s pretty clear in the case of most works of art that they are, in fact, works of art. What it communicates to you might be entirely different from what it communicates to me, and it may not communicate anything to either of us, but art as a classification is pretty easily sniffed out by anybody who makes a legitimate attempt to engage the material.

The strawman in this argument is always something along the lines of, “Oh, they could smear excrement all over the wall and call it art, but I wouldn’t.” In reality, very few examples of actual art would be anywhere near that obtuse. Somebody indeed might call some poop on a wall art, but they could also call a cow a vegetable. There’s no law stopping them from doing so…it’s just up to us as individuals to know that they’re incorrect, whether deliberately so or innocently confused. Either way, they’re wrong, and the cow doesn’t become a vegetable to one person and not another, simply because that’s what somebody said it was.

Art is recognizable because it has notable conflagration of themes. The components of the work of art, whatever the medium, mean something. The absence of other components also means something. The fact that they’re arranged in whatever way they’re arranged means something. Art, in other words, has meaning. We can argue all day about what that meaning is, but we shouldn’t be arguing over whether or not a meaning can be experienced.

The Binding of Isaac is obviously a deliberately crafted piece of art that is not only consistent unto itself (and therefore free of the nonsensical “shit on a wall” brush-off) but its themes are plentiful and overt. There’s no question that The Binding of Isaac has meaning. You may interpret it to be something other than I interpret it to be, but the foundation for interpretation has been laid, and sturdily.

The Binding of Isaac is obviously a deliberately crafted piece of art that is not only consistent unto itself (and therefore free of the nonsensical “shit on a wall” brush-off) but its themes are plentiful and overt. There’s no question that The Binding of Isaac has meaning. You may interpret it to be something other than I interpret it to be, but the foundation for interpretation has been laid, and sturdily.

Isaac, as a character, is a little boy who lives with his highly religious mother. The plot of the game sees poor Isaac fleeing through the basement to escape his mother, who believes she’s been called by God to re-enact the biblical account of Isaac and Abraham. Isaac fights monsters and his own psyche (often both at the same time) and uses his tears as projectiles. His sadness manifests itself as the pitiful creatures that he attacks, his mother-inherited disgust for his own physical form is reflected in the piles of dung and hideous representations of human body parts scattered around the dungeons. Between levels Isaac is haunted by a randomly summoned memory of himself being humiliated by his mother or his peers. Isaac is a damaged soul, and so is his mother. The difference is that Isaac is on the receiving end. He is powerless. He has no weapons, and he has no clothes. He seems doomed to fail. Due to the random nature of the game, he often is. There’s enough in that brief synopsis to unpack for weeks. This game has something to say. It may not always be sure what it wants to say at any given time, but that’s okay…we’re not always sure about what we’re hearing.

The strongest corollary for me here is Pink Floyd’s masterpiece concept album The Wall. The overbearing mother and the feeling of isolation and worldly entrapment are parallel themes between the two works, and just as Pink Floyd hooks unsuspecting listeners with the familiar rocking satisfaction of “Young Lust” or the anthemic sadness of “Comfortably Numb,” only to bombard them with far more complicated, despondent and often impenetrably central songs and cycles once they’re too far in to escape, The Binding of Isaac seduces that area of our brain that loved The Legend of Zelda and would love to play a gross parody of it…only to strip, disarm and humiliate us, and then force us to fight our way back toward the light…any light.

A work featuring such a questionable representation of God should certainly cause us to question the nature of God ourselves. No, not necessarily in real life, but within the universe of the piece of art. Does God exist there? Isaac’s mother thinks so…but Isaac, in the situation from which we are trying to free him, probably shouldn’t. What kind of God would really command this? Or is there no God? Or is there a God who was misinterpreted? Or perhaps a God who doesn’t even realize any of this is happening to one of His creatures.

The game seems to suggest, I’d argue, an absence of God. After all, one of the first differences Legend of Zelda fans will notice is the lack of a definite map. Every time the game begins, the levels are generated randomly. Bosses are mixed up, items are scrambled or missing, and sometimes a good portion of the areas will be inaccessible, because the game didn’t provide you with the key you needed before you found the door. The Legend of Zelda had a God. (Or, actually, three goddesses.) Things were reliable; Hyrule was a fixed commodity with an unseen force holding it all together. One room always led to another, and with enough time and practice, you could come to know what to expect. There was a heavenly constant that maybe couldn’t help you out of every jam, but could at least prevent the universe from reknitting itself beneath your feet, and leaving you in a completely different place from what you were logically led to expect.

The Binding of Isaac has no such presence. Every step is fraught with danger, and while you may stumble blindly into the next room to find a helpful upgrade, you’re just as likely — or, probably, more likely — to find a powerful foe you’re ill-equipped to conquer. You can’t rely on your memory, and Isaac can’t count on your familiarity with his predicament. Every time you play the game, the poor kid is cast into an entirely different world of entirely different chaos. And it’s brilliant.

The Binding of Isaac has no such presence. Every step is fraught with danger, and while you may stumble blindly into the next room to find a helpful upgrade, you’re just as likely — or, probably, more likely — to find a powerful foe you’re ill-equipped to conquer. You can’t rely on your memory, and Isaac can’t count on your familiarity with his predicament. Every time you play the game, the poor kid is cast into an entirely different world of entirely different chaos. And it’s brilliant.

I think people question games like The Binding of Isaac as art because they’re obscene. (It explains their shit-stained-wall fall-back, too.) There’s some bizarre sort of reluctance to allow obscenity and art — as classifications — to intermingle, and I’m not sure why that is. Something might be obscene, they feel, or something might be art, but it certainly can’t be both. It’s an almost — ahem — puritanical outlook, and it’s dreadfully incorrect. We’ll touch on each of these pieces again in the future, I’m sure, but take a look at the Holy Trinity of Obscenity as Art: Ulysses, Lolita and Gravity’s Rainbow. From masturbating in public to pedophilia to the sexual consumption of human excrement, these books can often be utterly repugnant. And yet there’s a beauty in that repugnance. It’s not the stories they tell, it’s how they’re told. It’s not the content, it’s the context. It’s not the detail, it’s the meaning. They represent masterful artists painting repulsive portraits in language we can’t help but feel moved by. The Binding of Isaac is moving in its helplessness, in its despair, and in its ruthless, relentless tragedy. It’s an unpleasant experience, but it’s beautifully executed.

It’s also, however — getting to our third point about The Binding of Isaac as a product — unsellable. At least that’s how Nintendo feels, and, as much as I respect the game, I have to agree with their decision. They are, after all, a business first and foremost. Publishers were reluctant to touch the novels listed above, and while it might seem fun to point at the obscenity trials that plagued the comparatively-tame Ulysses, they had a point, and that point was to accurately reflect the opinions of the other human beings who occupied the world around James Joyce. Yes, many of them found Ulysses to be gorgeous and important, but others found it to be disgusting and downright criminal.

Again, I’d argue that no matter what they felt about the book, they had no right to claim it wasn’t “art.” They did, however, have every right to boycott the publisher, and Joyce, and anyone else associated with the book. After all, as consumers, their strongest vote is always in their wallet. They could stonewall publication, protest shops that carried it, and burn extant copies in the street. That much was their right. They had no right to claim it wasn’t art, but they had every right to decide they’d rather not share a world with it.

The Binding of Isaac is a difficult to stomach game that both subverts and perverts one of the best known stories of the Bible. It skewers blind faith, it punishes a naked child, and it repulsively de-sanctifies the human body. It’s mean-spirited and cruel, determinedly evil and unapologetically crass.

But it’s art. And while art has every right to a spotlight at an exhibition for those who wish to see it, it does not have an inherent right to be offered as a digital download beside the classic NES games that inspired it. Nintendo has decided that it would rather not place The Binding of Isaac in a shop next to Super Mario Bros., and I can’t say I disagree with that decision, or that I’d have made it differently.

But it’s art. And while art has every right to a spotlight at an exhibition for those who wish to see it, it does not have an inherent right to be offered as a digital download beside the classic NES games that inspired it. Nintendo has decided that it would rather not place The Binding of Isaac in a shop next to Super Mario Bros., and I can’t say I disagree with that decision, or that I’d have made it differently.

I think it’s a great game. I think that a lot of gamers will be missing out on it because of Nintendo’s decision. But I can’t begrudge them, because as a product, it’s a bonfire and a public relations nightmare waiting to happen. Ulysses found a distributor, and so has The Binding of Isaac. The distributors who turned them down turned them down for a reason, and I respect them for that. In neither case did the reason have anything to do with withholding a work of art from those who might want to experience it; it had to do with staying in business. And, as businesses, that wasn’t a totally ridiculous decision.

Nintendo just said they’d rather not sell it. They never said it wasn’t art.