It’s election day here in America, so make sure you get out and vote. It’s important. I learned that the hard way, since the first election I was old enough to vote in was Bush vs. Gore and I did not cast a ballot, assuming democracy would sort itself out. We all saw how well that went, so I won’t be missing any — admittedly small — opportunity to shape this country’s future again.

Anyway, some of you may have seen this before as it’s certainly nothing new, but it’s been circulating again in light of election season and, at last, I’ve felt compelled to respond to this thing.

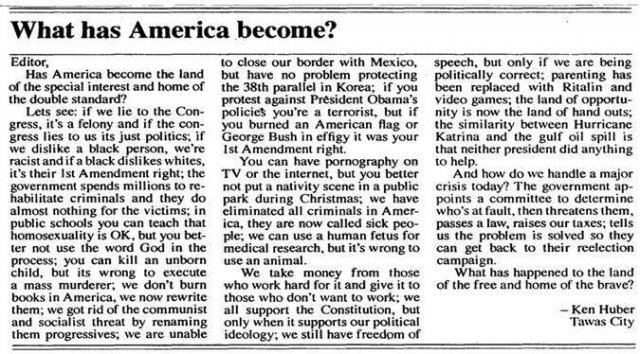

It’s ostensibly a letter to the editor by one Ken Huber, but I’m not entirely convinced it was ever published anywhere. Regardless, I think it pretty accurately reflects a certain type of mindset, even if the particular words don’t belong to the person to whom it’s attributed. And it’s a dangerous mindset. A rotten one. I thought I would take a moment to reply.

The text is viewable in the image above…if there are any errors in the transcription below they are not deliberate…feel free to let me know and I will correct them.

Editor, Has America become the land of special interest and home of the double standard?

Remember these words, as Huber frames “special interest” and “double standard” as bad things — rightly so — when he opens the letter, but then spends the rest of his time arguing in their favor.

Lets see: if we lie to the Congress, it’s a felony and if the Congress lies to us its just politics;

It should indeed be a crime to lie “to the Congress.” I genuinely can’t imagine a situation in which lying to the government should be excusable, so I don’t know why it’s a bad thing that those found guilty of bearing false testimony in a court of law should be punished for it.

Also, I’m not sure I’ve ever heard anybody say “It’s just politics” when a congressman is caught in a lie. Depending upon the severity of the lie sometimes one’s own party members will attempt to spin it in a less damaging way, but did anybody anywhere brush off the mistruths of Rod Blagojevich, Anthony Weiner or Todd Akin by saying “That’s just politics?”

We have a free press, and we take our congressmen to task for what they say and do, on both sides of the divide. Neither party gets a free ride…at the very least, they get called on it by the other party…one of the relatively few — but pretty clear — benefits of partisanship.

if we dislike a black person, we’re racist and if a black person dislikes whites, its their 1st Amendment right;

We’re still toward the front end of Huber’s second sentence and already he’s arguing overtly for a right to hate. That sure didn’t take long.

Read again what he wrote here, and then consider this alternative: “Why is it that I am always kind and friendly to my black neighbors, but I don’t feel the same courtesy in return?”

Same core wish — for a two-way sense of fairness — but the way in which it’s expressed says worlds about what we wish to do with that fairness. Huber doesn’t want to love his brother or be loved by his brother. He sees that his brother dislikes him and so he’d like the right to dislike him back.

Which is odd, because he does already have that right. Yes, if we dislike a black person because they are black, that is racist…however we have the right to dislike them for whatever intolerant reason we choose. We can’t openly discriminate against them, we can’t commit crimes against them, and we can’t enslave them, but last I checked there were plenty of racist morons roaming the street, longing for the glory days of the universal oppression of everyone who wasn’t them. Here, Huber would like us to think that he is oppressed, because we’ve robbed him of his right to oppress others. And that’s damned disgusting.

Also, it’s pretty funny that he thinks black people get an easier ride with the law than whites. That’s an ignorance so active it must hurt.

the government spends millions to rehabilitate criminals and they do almost nothing for the victims;

I still don’t know what he’s arguing for here. “Do something for the victims” is pretty clearly what he’s trying to say, but what is “something?” And “victims” of what? Both of those things need to be defined because there’s way too much room for interpretation there.

And isn’t the rehabilitation of criminals “something?” If it gets them off the streets and prevents them from committing crimes, then that’s “something” the government is doing for all potential “victims.”

Perhaps he wants free health care for victims of crimes. Well, good news for him: President Obama’s been pushing for that free health care for a while now, while the folks Huber keeps voting into office prevent him from getting it passed. Nice job, Ken.

in public schools you can teach that homosexuality is OK, but you better not use the word God in the process;

I’m unaware of any school, public or otherwise, that explicitly teaches that homosexuality is okay. More accurately they’re just not allowed to teach that it’s a Bad Thing. And why anyone would want to use the word “God” in the process of teaching the complete awesomeness of gayness is beyond me.

you can kill an unborn child, but it is wrong to execute a mass murderer;

37 states practice capital punishment currently, and the most recent Gallup poll on the subject (2011) found that 61% of Americans were in favor of executing those found guilty of murder, with only 35% opposing it. That’s a clear majority, and it’s also the lowest level of support ever found by the Gallup poll…it’s usually even higher. So I’m not sure where Huber gets the idea that America feels it’s wrong to execute a mass murderer, and he’s pretty clearly using that only as a counterpoint for his stance on abortion which, as we all know, is mandatory in all cases of pregnancy now.

we don’t burn books in America, we now rewrite them;

Citation — and significant clarification — needed.

we got rid of communist and socialist threats by renaming them progressive;

First of all, please stop lumping Communism and Socialism together. Second of all…what?

we are unable to close our border with Mexico, but have no problem protecting the 38th parallel in Korea;

We have significant problems with Korea, Ken. Far morseo than we have with Mexico. Of course, they’re also completely different problems and one might say it’s impossible to compare the two without looking foolish for doing so.

if you protest against President Obama’s policies you’re a terrorist, but if you burned an American flag or George Bush in effigy it was your 1st Amendment right.

A revisiting of Huber’s earlier black/white rant, this time naming particular individuals.

First of all, give me an example of one person who’s protested against President Obama and, due to that fact, has been tried as a terrorist. Just one, since this seems to happen all the time. That shouldn’t be so hard.

Heck, just look at Bill O’Reilly, Rush Limbaugh, Glenn Beck…those guys protest Obama on a daily basis, so I have to assume they’ve each been labelled terrorists and punished to the fullest extent of…

…oh, wait. No, they’re still around, and still given a platform with which to spout their anti-Obama beliefs. So where did we get this idea again?

And, yes, it is within your rights to burn someone in effigy. That’s why it’s allowed…because you’re burning someone in effigy. It’s the difference between a political statement and an attempt at assassination. Nobody’s going to jail for it, whether it’s Obama, Bush, or Harry Potter you’re burning.

You can have pornography on TV or the internet, but you better not put a nativity scene in a public park during Christmas;

What correlation is there at all between these two things? Television and the internet are both private venues for information retrieval. If someone chooses to view pornography, that’s within their rights. Why wouldn’t it be? People can choose what to view in both cases. If they want to see the pornography they can and if they don’t wish to see it they can avoid it.

A public park however is…well, public. Which is to say it is not something people should have to avoid, nor should any one person or group of people decide which religion is endorsed by it. (Also pornography, last I checked, is not a religion, so maybe, just maybe, this isn’t the comparison he should be trying to make.)

Somehow I don’t think Huber would be in favor of a giant, mechanical Mohammed being installed in a public park, so why would he be in support of a nativity? Easy…because that reflects his special interest. And his double standard means he’s perfectly fine relegating the beliefs and feelings of others to the sidelines in favor of his.

we have eliminated all criminals in America, they are now called sick people;

I thought we were rehabilitating criminals?

Who knows. Maybe in the time between writing that observation and this one America happened to eliminate all criminals and he just didn’t have time to delete that before mailing it to the editor.

We do indeed refer to criminals as “sick” very often. And they very often are sick. I’m unaware of anyone who’s stopped referring to them as criminals, however.

we can use a human fetus for medical research, but it is wrong to use an animal.

We can use an animal fetus for medical research as well. And we use animals at all stages of development for medical research. We can’t use living human beings of any age for medical research unless they personally consent, and even then there are far more stringent guidelines for testing on humans than there are for testing on animals.

We take money from those who work hard for it and give it to those who don’t want to work;

There are those who don’t want to work, and some of them do indeed defraud government welfare programs. There are also many more who can’t work, or can’t find work, whose families are sustained by temporary government assistance.

The fact that there are those who abuse a system does not suggest that the system itself is a problem.

we all support the Constitution, but only when it supports our political ideology;

I agree with this, Ken. In fact, I’d raise your letter high as proof of that very fact.

we still have freedom of speech, but only if we are being politically correct;

Your letter is not “politically correct” in the slightest, as I’m sure you’ll agree. Yet it’s also not been censored. You’ve proven yourself conclusively wrong by simply making that observation.

parenting has been replaced with Ritalin and video games; the land of opportunity is now the land of hand outs;

Nothing much to say here. The hand-outs bit is dealt with above, and I don’t know why he wants the government to enforce standards of parenting. Wouldn’t that be more in line with the imaginary Big Brother government controllapalooza he’s raging against above?

the similarity between Hurricane Katrina and the gulf oil spill is that neither president did anything to help.

A bit reductionist here, but honestly that’s pretty fair. I will say, however, that there’s a difference between not helping actual human beings who are being displaced and dying, and not helping a body of water that’s seeing substantial environmental impact. Certainly a humanitarian like Huber — who just moments ago was preaching how much more important human life is than animal life — would see that.

Also, hindsight really works against this one, as Obama’s currently dealing with the devastating effects of Hurricane Sandy…and he’s dealing with them in an active way that Bush did not do with Katrina. Comparing apples to apples, we have a clear winner here.

And how do we handle a major crisis today? The government appoints a committee to determine who’s at fault, then threatens them, passes a law, raises our taxes; tells us the problem is solved so they can get back to their reelection campaign.

Apparently determining who is at fault before dishing out punishment is a Bad Thing to Huber. So is passing a law to prevent it from happening again, and asking citizens to chip in so that this new law protecting them from a “major crisis” occurring again can actually be enforced.

What has happened to the land of the free and home of the brave?

You demonstrated that neither of those things has gone anywhere simply by complaining that they’re long gone. You’re brave and free enough to write what you feel, and newspapers are brave and free enough to print it, and everyone else is brave and free enough to respond to it as they see fit. Congratulations, Ken…your imaginary nightmare land never existed.

– Ken Huber, Tawas City

So why get out and vote?

Because this man is unquestionably turning up to the polls.

Do your part, America.