Note: Third Editions provided me with exactly one physical copy of each book in exchange for a review. No other compensation was offered, asked for, or delivered. The opinions you read here, as always, reflect my honest feelings as fully as the limitations of the English language will allow.

I’m a fan of Boss Fight Books. From the publication of their very first batch of titles, I’ve been following them closely, as excited about each new wave of announcements as I once was on Christmas morning. Sometimes they write about something I know well, and I look forward to the gift of experiencing a game through somebody else’s eyes. Other times it’s about a title I don’t know well at all, and I get to learn about the experience the game offers from afar, whether or not I end up particularly interested in playing it myself.

It’s a great series of books, and while there are a number of them that didn’t really resonate with me or work for me, I’m sure that those same titles are ones that hit other readers in genuinely profound ways. I don’t know how much agreement there is about which books are best and which are weakest, because they’re all so decidedly different. So unique. They’re like the people who write them; you’re going to immediately click with some, and you may never click with others.

I’m not complaining. I think that’s a selling point, especially if you dive in and grab a bunch of titles at once. The ones you end up enjoying the most could well be the ones you least suspected.

I mention Boss Fight Books for two reasons. Firstly, because the myriad different approaches demonstrated within that series – emotional, analytical, autobiographical, snarky, reverent – are appropriate for the still-young field of games scholarship. As a relatively new medium, and an interactive one, there is not yet an established, accepted method of writing about them seriously. Boss Fight Books represents the excitement at that new frontier, the giddy experimentation of holding up a game that may never have been given serious artistic consideration before, and creating, from nothing, the very discussion that will keep that game alive.

If I’m romanticizing that, so be it. I’m a romantic. I love art. I love discussing art, dissecting art, and sharing in somebody else’s passion. Boss Fight Books is a publisher that certainly does not lack for passion.

The other reason I mention them is that when Third Editions approached me for a review, Boss Fight Books was the very first point of comparison that crossed my mind.

On a very superficial level, I expected them to be quite similar. In fact, I wondered if this series could be theoretically absorbed into the other, and, if so, how well it would fit in.

I think that’s something Boss Fight Books should take as a compliment; they established a standard for games scholarship that anyone else who strolls into that area will have to live up to.

Third Editions does live up to it, but it also does so much differently that it almost doesn’t matter. The two series don’t – and shouldn’t – jostle for direct shelf space. Their intentions might seem similar, but their executions are very different. And they both work very well.

Full disclosure: I’ve pitched ideas to Boss Fight Books in the past, which is part of the reason I haven’t featured them directly on this site. I wouldn’t want there to appear to be any kind of conflict of interest should something work out between me and them in the future. I’d like to think my readers believe in my sense of integrity and that I wouldn’t ever dream of giving someone a good review in the hopes that I’ll get something out of it later, but mainly I wouldn’t want my words to seem retroactively hollow should one of my pitches actually pan out. (“Of course he likes them…they published his 750,000 word manifesto on Bubble Bobble.”)

Third Editions, though, is new to me. I don’t know any of the authors involved, I don’t know the publisher, and I know nothing of their plans for future books. In short, there’s nothing between them and me that anyone should even be able to misconstrue as a conflict, and I was free to approach the three books they sent me as a reader and a critic.

I’m glad I had that opportunity, because they were great.

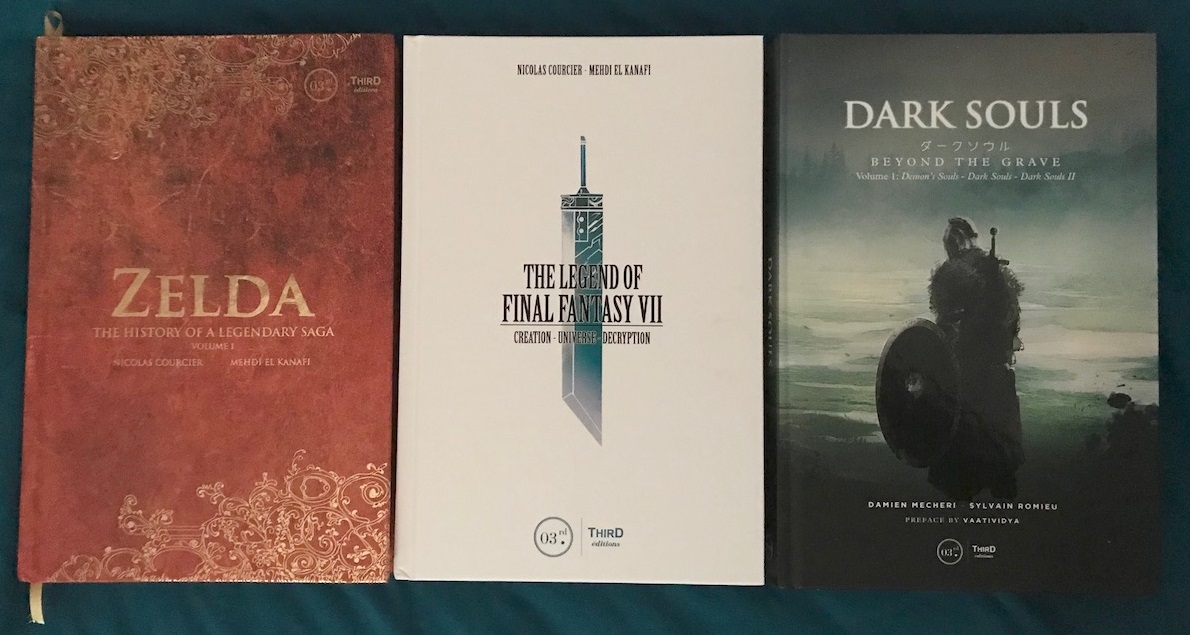

The titles they sent me were Zelda: The History of a Legendary Saga, The Legend of Final Fantasy VII, and Dark Souls: Beyond the Grave. (Two other titles, covering Bioshock and Metal Gear Solid, are also currently available.)

In the case of Final Fantasy VII, the book is almost entirely about that individual game. The other two books, though, are about the series in general. This is in contrast to the Boss Fight Books releases, which almost exclusively focus on a single game each.

Each of these books is attributed to two authors. How closely the pairs worked together, I can’t personally say. But I will say that the books certainly read as cohesive works, and I didn’t notice any issues in terms of a shifting of authorial voice. They read well, they’re written clearly, and section breaks are meted out generously enough that no topic overstays its welcome.

That would be the whole of my general feedback if not for this fact:

These books are gorgeous.

As strong as the writing is – and we’ll discuss that momentarily – there’s no denying the books’ sheer physical appeal. These are some absolutely beautiful publications, and for fans of the covered games, I’d say they’d make for incredible gifts for that reason alone. These have value simply as collectibles, and I think it’s worth pointing that out. They’re lovely, and the photos I’ve taken do not do them justice.

Furthering their value as physical gift pieces, they’re all printed on impressively thick paper, which was a pleasant surprise. They each also have a color-coordinated ribbon for holding your place: gold for Zelda, white for Final Fantasy VII, and black for Dark Souls. I’m assuming this qualifies as a bonus, but I have to admit I’ve always found these ribbons difficult to use; I keep worrying that I’ll close the book on them wrong and crease them. That’s obviously just one of my many neuroses, but I’d be curious to hear if anyone out there has strong feelings about them either way.

Visually and physically, the books are great. It is, however, worth noting that they don’t contain any art assets. No illustrations, maps, or anything along those lines. That’s fitting for the approach the authors take, and their absence wasn’t felt to me as a reader, but if that’s what you’re looking for, it’s good to know in advance.

In my position –- reading all three books in fairly quick succession –- I will say that the font size for Final Fantasy VII took a moment to get used to. Zelda and Dark Souls use a large, easy-to-read font, but Final Fantasy VII uses one that’s noticeably smaller. I don’t think it’s anything that should be a deal breaker for somebody interested in that book alone, and I will emphasize that it’s not difficult to read, but it was rather jarring coming off of the easier fonts of the other two. As first I thought this was done so that the books could be kept of a relatively equal number of pages, but Zelda has 221 numbered pages, Dark Souls has 303, and Final Fantasy VII has 199, so I’d guess it could have afforded a larger font after all.

But, well, what of the actual content?

I have to admit, it’s a bit difficult to review that.

See, the approach of the Third Editions authors is largely clinical. It’s fact-based, with little in the way of personality or conversation. That’s not a problem at all, but it does make reviewing them difficult.

Typically, I’m used to novels. Fiction. Which allows me to discuss (and judge) things like style, pacing, creativity. Non-fiction is a lot different. I can judge a work of non-fiction on how much I learned and whether or not it kept me engaged, but beyond that, I’d struggle for much to say. And, of course, I’d prefer not to simply regurgitate the information the books provide. (That’s, y’know, what the books are for.)

This is also another area in which a comparison to Boss Fight Books might be helpful. Those books weave (to varying degrees) the information they provide into and within more personal narratives. Those do provide an element of creative expression, even while relaying relatively dry facts and histories.

So, hey, bear with me as I feel my way through this, and learn to review something in a way that’s pretty new to me.

I will say that the writing is solid. The chapters are clearly delineated, with very little overlap in subject matter, which means that you can either read them straight through (as I did), or hop around to the particular subjects that interest you. Reading straight through won’t bury you in redundant information, and hopping around won’t strand you without context. That’s nice.

It’s also worth pointing out that these three books are English translations from French originals. I can’t speak much to the actual translation process, but I can say that if I didn’t know they were originally written in another language, I wouldn’t have been able to guess. The English versions don’t come across as clunky or confusing at any point, and I’d guess their translator has done impressive work in that regard.

Ultimately, I think I can also vouch for the value of these books as informative texts. I personally know quite a lot about the Zelda series, a decent amount about Final Fantasy VII, and very little about the Dark Souls games. In each case, however, I learned a lot. This was especially surprising to me in the Zelda book, as I was more or less convinced I’d read everything I’d ever have to read about that series. It was a great surprise to me that there was still a lot for me to learn in terms of the design of those games, their development, and their larger inspirations.

For that reason alone, I’m confident in saying that these books go well beyond what you would find in the standard wikis and retrospectives you’re likely to read online. And that’s important, I feel, because with so much information available in so many formats at our fingertips, it may be difficult to justify spending money on what may turn out to be little more than a printed version of some small fragment of that information.

Third Editions does actually bring new (or at least uncommon) information to the table, though, and I certainly enjoyed the professional, clean approach taken with the material here far more than I enjoy the amateur writeups I usually find online. The quality of the writing and presentation here justifies the purchase price for fans of these games, and you’d be hard pressed to find better ways of learning about them.

In fact, these titles read almost like textbooks at times, and I mean that as a compliment. They successfully present themselves as definitive sources, and it’s easy to imagine them being used in the college lectures on video games that are certain to become more commonplace in the future. They serve as reference materials and study guides at once, providing relatively little in the way of interpretation but giving readers all of the tools they’ll need to interpret these games and series themselves. It lays the groundwork, in other words, for designers and gamers to reach the next level of understanding. As odd as it may sound in regards to books about video games, these are genuinely educational.

And, frankly, they’re pretty great. I was given these books in exchange for a review, but I’ve also placed an order for the Bioshock book, as I think that is a series that will lend itself very well to the Third Editions approach. I didn’t just read these and enjoy them…I read them and wanted more.

For fans of any of these games, especially fans who are interested in studying them, it’s hard to go wrong with Third Editions. They’re well-written, surprisingly informative, and deeply comprehensive. They look and feel great, and they’d make a great gift for gamers and scholars alike.

Whether or not the more clinical, detached approach will appeal to you is something I can’t answer. If the kind of video game chat you enjoy is held with good friends over a long night of drinking, then Boss Fight Books is probably a better fit for you. But if you’d prefer video games to get the exhaustive, thorough, scholarly treatment films and music have been getting for decades, give Third Editions a spin.

Personally, I enjoy them both for different reasons. But I look forward to seeing what Third Editions covers next. It will be interesting to see if it achieves the staying power Boss Fight Books has. I certainly wish them luck, and I hope they find the exposure they deserve.

You can view and purchase the books available from Third Editions right here.