Way back when I started this project (almost two years ago, for those keeping track of just how much of my life ALF has sucked away) I grabbed a list of episode titles from Wikipedia. That ended up serving as the base for my main ALF page, with the titles linking to the reviews as they were written. In doing so I didn’t deliberately look at the plot summaries, but, of course, I saw some of them. One of those summaries was for this episode…and though I’ve had some pleasant surprises along the way, this is the one I kept looking forward to.

See, I’m a sucker for “cute” stories. I don’t know why…maybe it just taps into my memories of childhood and I let my guard down. But ALF getting an ant farm, and being overcome with grief when he accidentally destroys it? I like that idea. It’s no more creative than the show’s storylines usually are, but it sounds like a nice idea for a breather episode…and one in which ALF could actually have to process the emotions one feels when faced with the death of a loved one. It’s filtered through a silly $8 ant farm, but since the last time ALF dealt with death he was fisting Uncle Albert’s corpse in the back yard, I’m more than willing to give the show a do-over.

In short, “Funeral for a Friend” seemed to me like exactly the kind of episode I would enjoy. And…overall, I think I do. There’s a lot to like about it, certainly, even if it’s not quite the episode I wished it was. The best thing about it is probably its cute concept, when it should have been a series highlight.

Is that much of a complaint? No, probably not. “Funeral for a Friend” didn’t quite live up to its potential, but it blows 96% of ALF out of the water by virtue of the fact that it had potential, so that’s something.

Anyway, enough stalling; let’s get started! We’re finally on the final disc of season three, so let me just dig it out and…

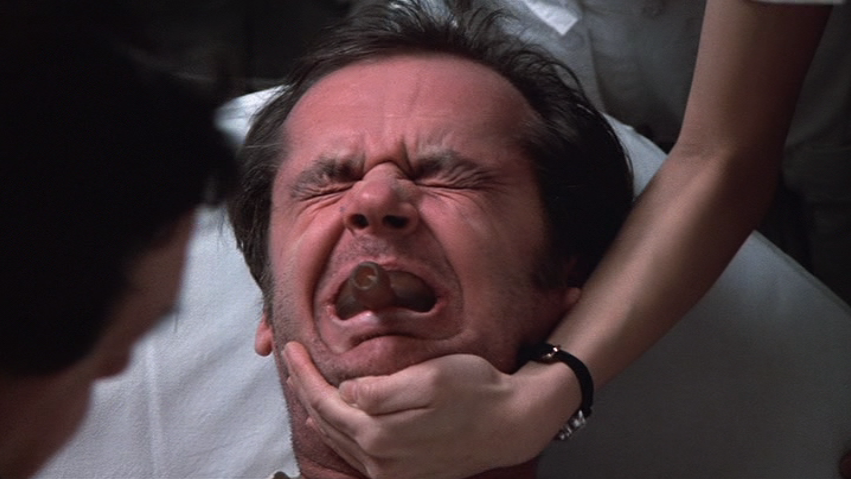

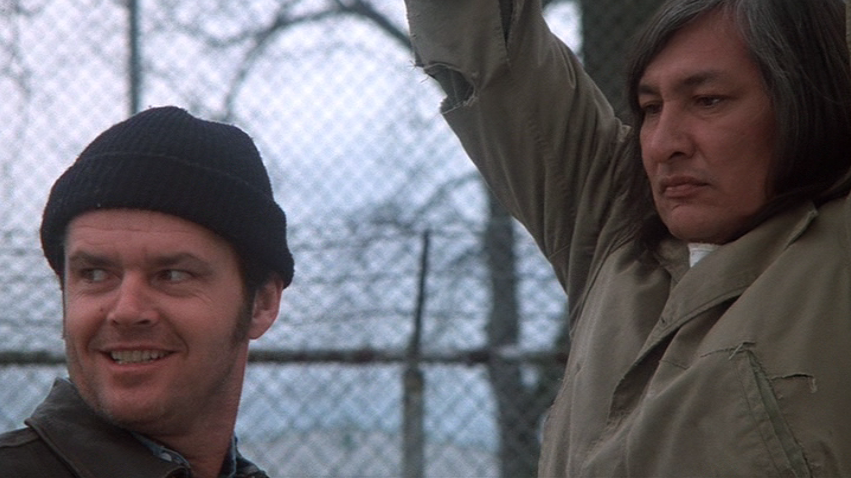

oh dear Christ no

Willie, I was looking forward to this. Why you gotta be so gross? He looks like he just caught me masturbating.

Anyway, the episode opens with ALF and Brian leafing through some book of animal pictures. ALF tells Willie that he’s picking out a pet, but Willie reminds him that they already have a cat.

Do you, Willie? Nobody’s mentioned it for weeks, and I don’t know if we’ve seen it since season two. I think Lucky got stuck under the house and none of you assholes noticed. You don’t have a cat anymore. You have a cat skeleton.

Brian gets to deliver some kind of joke. At least, I assume he does. The laughter kicks in and he rolls his eyes after saying whatever the fuck he said, but for all I can tell you he was speaking in tongues. It’s completely unintelligible.

I think it was some kind of irrelevant joke about how he’s taller than ALF now, but I couldn’t make out what he was saying because he’d accidentally sat on a testicle.

ALF suggests they get a horse, and I’m sad that Willie shoots it down so fast. Seeing ALF and Willie get kicked to death by a horse would instantly cement this as the best episode ever made.

After the intro credits ALF rides around the living room on a hobby horse. He does a John Wayne impression while wearing that actor’s iconic sleeveless jean jacket.

Come on. Surely ALF was low-budget, could it not afford another costume? So far this exact jacket has been deployed to make ALF look like Bruce Springsteen, a hippie, and John Wayne…three things that have no item of clothing in common, let alone this thing that a middle schooler on a class trip left behind in the NBC bathroom. If ALF ever has to dress as Abraham Lincoln he’ll probably be wearing this fucking thing.

Anyway, ALF makes a joke about the hobby horse driving splinters into the underside of his sack, so fucking fuck me for getting my hopes up.

Willie tells ALF that he’ll get a horse over his ugly, hate-filled body, so for fuck’s sake shut up about it. Then he puts an ant farm on the table.

ALF looks at it. He says, “You got me a pet beach?” …and that’s actually a really funny line. Not too obvious, not too silly…it’s one of those rare ALF jokes that you can laugh at without having to apologize afterward.

Seeing this ant farm brings back a lot of memories. I had one exactly like it when I was a kid. (I assume that many of you did, too.) Specifically I remember the fact that it didn’t come with ants. Willie’s does, which is fine, as this is television, and we don’t need to watch ALF dick around for 6 – 8 weeks before the plot can begin, but I definitely had to mail away for them.

I remember that because when they arrived, the ants were frozen. I don’t recall what we had to do to reanimate them, but when they were unfrozen two of them were stuck together at the head. Both of them were alive, but they couldn’t separate from each other; they were permanently melded forehead to forehead. After a long struggle, one of them decided to decapitate the other. The headless one died, of course…and the other one just had some other dead ant’s head stuck to its face for the rest of its life.

It was pretty fucking miserable. I think it taught me a valuable lesson about hating life.

Willie explains that ALF is a dumbass; this is a chance to observe the behavior of ants as they “work and play in their natural environment.” ALF calls him out rightly on green windmills and plastic trees not being a natural environment, but I find it much more objectionable that Willie thinks the ants are going to play.

Ants don’t play, Willie. They dig and they fall over dead. What you’re seeing are crack goblins. Take your lips off the glass cock for a few days and you’ll stop seeing cartoon characters everywhere you look.

Later on ALF is in the attic. Brian and Lynn come in to see how the ants are doing, and he says they suck dick; he can’t even teach them to fetch, speak, beg, or suck dick.

Brian agrees with him that ants are pretty fucking boring. Then again Brian has a pet space alien and can’t be arsed to spend time with it so his judgment is probably at least a little skewed.

Lynn has a welcome, human moment with ALF as she tells him the way her parents operate: if ALF is able to prove he’s responsible enough to take care of these ants, they might let him have a bigger pet. It’s exactly the kind of thing we get shockingly little of in this show: an observation about family dynamics. Lynn is somewhere between eighteen and fifty-six years old (depending on the episode), so she’s had a lot of time to learn about the way her parents react to things. Here, she’s passing on the knowledge. If ALF treats the ants like shit, then they’ll always be able to use that as justification for why he can’t have a better pet. If he treats them well, they might be willing to grant him a little more leeway.

It’s good, and ALF’s mildly confused response works well: “So if I take care of these ants I can have…what? Big ants?”

Look at that. Believable human moment punctuated by joke. It’s not that hard, ALF. When you give a shit, you do just fine.

Brian says that his first pet was a turtle, and ALF assures him that nobody even cares if he lives or dies, so there’s no way in fuck they care about his turtle. The kid wisely shuts up.

Lynn asks ALF, “Have you read this question and answer section of your ant watcher’s manual?” That’s a line Jack Nicholson wouldn’t be able to deliver naturally, so you can imagine how poor Andrea Elson trips over it. Honestly, try reading that out loud. The writers sure didn’t, or they’d have realized pretty quickly that no human being speaks that way without a spike through their brains.

ALF tells her, no joke, that he’d planned on reading it the next time he had to take a long shit. Sometimes I exaggerate in these reviews for humorous effect, other times something like this is said and I realize that even my wildest exaggerations are right within the show’s idiotic wheelhouse.

She reads aloud from the booklet and sure enough it says that ants play, which I’m still positive is complete bullshit. Ants don’t fucking play, ALF. They work themselves to death for the good of the colony. They have little or no sense of self, and exist solely to be productive little workers. Ants have been on Earth for over 90 million years, and at no point have any of them invented the beach ball. They don’t fucking play.

Oh, but wait! Brian and ALF conveniently see two ants “playing” just as she says that. The way this episode has panned out so far I genuinely expected the joke to be that these two assholes are watching some ants hump each other, but no. The ants are actually fighting.

Which is not quite the same thing as playing.

Like, not at all.

In fact it’s pretty damned close to being the opposite of playing, as these two insects are slowly hacking each other to death…an activity not commonly associated with one’s leisure time.

So the fact that they view this as evidence of “playing” is pretty stupid, but it’s still a lot better than hearing ALF compliment an ant on its cocksmanship.

Later on ALF throws a bunch of rice all over the house. Why? Is it because he’s a cunt?

Yes!

But, coincidentally, two of his ants are getting married. He invites Willie and Kate to watch the ceremony with him. It says a lot that in a scene like this, the least believable thing is Kate looking into the ant farm and reporting that the ants are dancing.

Fucking hell. Remember when Kate was a human being, and not the brain-dead pod person she’s been for what feels like this whole season? It’s actually really disappointing how far her character has fallen. Did I miss an episode in which ALF concussed her with a 5-iron or something?

Post-lobotomy Kate aside, I like the idea of what’s happening here: ALF is getting wrapped up in the lives of his little pets. He likes them, and they’re making him happy. Willie even takes ALF’s picture next to the ant farm, and that’s…really cute, actually. I like it when ALF gets to be a child.

Remember, he’s been on Earth for only three years. He’s still learning, and he’s still figuring out how to process things. Essentially, he is a child…just one that can articulate his feelings better than an actual three-year-old kid could. Or than Benji Gregory ever will.

The episodes that acknowledge that — such as this one — tend to at least be interesting. So, yeah, the episode sucks so far, but this is an adorable concept, and I love the fact that they’re exploring it.

Willie asks ALF if he’s happy they didn’t get a horse, and ALF responds with one of those song-lyrics-as-jokes things that WE ALL LOVE SO MUCH. This time he recites the theme to Mr. Ed.

You lucky people.

In the attic both Lynn and Willie are leaving presents for ALF while he’s in the shower. Lynn’s gift is an “Alan Thicke’s World of Ants” calendar, which I won’t even pretend to understand as a joke, but which I like anyway for some reason. Probably the specificity of it. I have no clue if Alan Thicke is an amateur myrmecologist in addition to being an actor / failed talk show host, but it almost doesn’t matter. A yearly calendar devoted to his findings is a funny idea, whether or not it has any basis in reality.

Willie’s gift is a bunch of little farm toys to display with the ants…and I love, love, love the fact that these two are encouraging ALF’s new hobby. It’s so rare that anybody on this show seems happy, so it’s nice that the one time it happens, the others join in and don’t try to crush it. Also, it must be a really nice change of pace for them to have ALF engaged in something that doesn’t involve rape.

There’s a lovely little moment when Willie finds the photo he took of ALF with his ant farm, on a table beside replacement sand, food, and a model he built of an ant. It’s a super cute moment, and it hints at a warm side of ALF that we almost never get to see. Willie beaming is pretty nice, too, since he so rarely shows any kind of pride in his slutty daughter or learning disabled son.

I really, really like this part.

But then Lynn sees that the ants are dead.

Well, that’s that, then. The good scene was fun while it lasted. See you in another 16 episodes, everyone.

It turns out that ALF left them by the window and they baked in the sun. Granted, we find out that he’s been in the shower for an hour, and that’s a long shower, but is that enough hot sunlight to kill ants?

I honestly don’t know. I’d imagine they’re more resilient to heat than most pets would be, but I guess I can’t say that for a fact. If one of you assholes had bought me an Alan Thicke’s World of Ants calendar I wouldn’t have to do all of this guesswork.

ALF comes back from his shower and they break the news to him. It’s a sweet moment that doesn’t get too sappy, but the emotion that is present is pitched quite well. In disbelief, he says, “An hour ago, they were working the farm!”

Willie says, “And now they’ve bought it.” This is a historic moment, folks. Max Wright got a joke that didn’t involve ALF slugging him in the nuts.

After the commercial, ALF is moping alone, sitting quietly with his ant model…which he’s turned upside down out of respect.

Willie brings him a sandwich, but ALF is too sad to eat. Willie asks, “Do you want to talk? I’m trained in this area.” And…

wait.

wait.

Did…am I…

Is this a dream? Or is Willie actually acting like a social worker?

Assholes! WILLIE IS ACTUALLY ACTING LIKE A SOCIAL WORKER

This is a genuine shock to me, since he usually addresses his family’s problems by bludgeoning hobos and stabbing farmers to death with pitchforks. I…I am gobsmacked. I really don’t know how to react. It’s as though this episode had such a good idea at its root that it’s even managed to affect Willie, a guy who’s seventy-four years old and has yet to be affected by an interest in intelligible diction. “Funeral for a Friend,” you magnificent bastard.

What’s more, the writing here is pretty good. Willie really does get to be a social worker for once. For instance, ALF says that the ants might have survived if he hadn’t taken so long in the shower…and Willie tells him that that’s okay; it’s common to experience guilt when something you love dies.

ALF asks if anger is natural, too, because he’s mad that Willie got him the ant farm in the first place…and it’s not just a sitcom moment. Willie tells ALF that, yes, it is natural, and it’s healthy to work through your emotions like this. He encourages him to keep going.

For the first time in this entire fucking idiotic show, I actually believe that Willie has the job that people keep telling me he has. Fuckers…this is not bad.

ALF does make some crack about also being mad at CBS for canceling Frank’s Place…and that’s a reference I don’t get. I’ve never heard of the show. Looking it up reveals that it is actually still held in pretty high esteem, though it never made it to a second season.

I feel as though the joke is that ALF liked a shitty TV show or something, but consensus says that it wasn’t that shitty. It was a racially-charged comedy/drama starring Tim Reid, who played Venus Flytrap on WKRP in Cincinnati. That…sounds kind of interesting to me. I’d watch it.

Maybe this reference was just the writing staff’s way of venting frustration that a pretty good show on another network wasn’t given a fair shake. But I’m at least mildly worried that the joke is that ALF watched a “black people” show. God knows what he would have shouted at the television.

Willie offers to buy ALF another ant farm, which is a reasonable solution, but ALF was attached to those ants, which is a reasonable response. He compares it to getting Willie a new wife if Kate died, which is certainly overdramatic but makes a fair point about the scale of loss. Something that seems small to outsiders might be huge to the person who is experiencing it. Willie realizes this, which is why he doesn’t bitch slap ALF.

It all fits as part of a surprisingly well-handled discussion about grief, and I really like this version of Willie. (Have I ever said that before?) Pity he doesn’t even survive to the next scene.

Yes, this being ALF, we need to follow that very good exchange with a prolonged view of Willie having nocturnal emissions.

God. Dammit. ALF.

He writhes around and giggles because he thinks his wife is giving him the first blowjob he’s had in years (The National Enquirer is NOT to be believed), but it turns out he just has a bunch of ants crawling all over his genitals.

Try to guess how much of that I made up. You’ll be pleasantly horrified.

Ants are all over the house because ALF left a shitload of food out. Willie and Kate go into the kitchen to survey the mess, and Kate gets to be Kate again by burning holes through ALF with her eyes. Man, I’ve missed her. I guess the filth and infestation shocked her back to life. I’ll take it.

Kate really has been a shell of her former self for too long, but this scene almost makes up for it: Willie tells her to go into the living room and he’ll do the cleaning, but she suggests burning down the house and starting over.

And, man, that’s the Kate I’ve missed. Overall I don’t know if Anne Schedeen has finally given up on trying to make the most of this awful show, but it’s nice to have her back…however briefly.

It turns out that ALF invited all the world’s ants into the house to make some kind of amends for killing a bunch of them. Willie says he has an idea about how to handle this, and Kate tells him to go fuck himself; this time ALF is hers.

It really is the best Kate scene we’ve had in ages. Especially when Willie stops her from murdering ALF and suggests that they hold a memorial service for his dead pets.

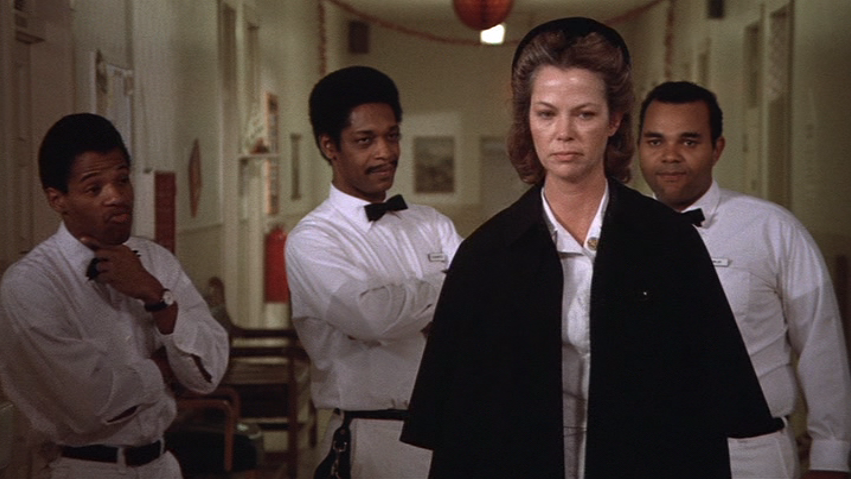

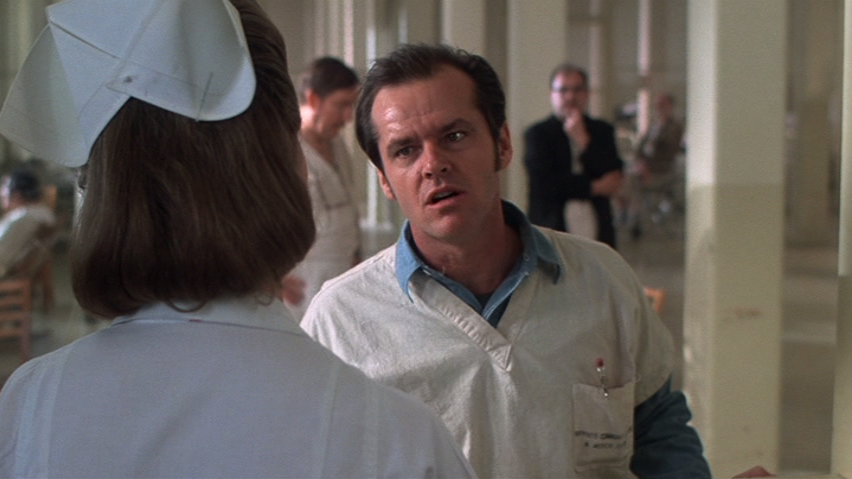

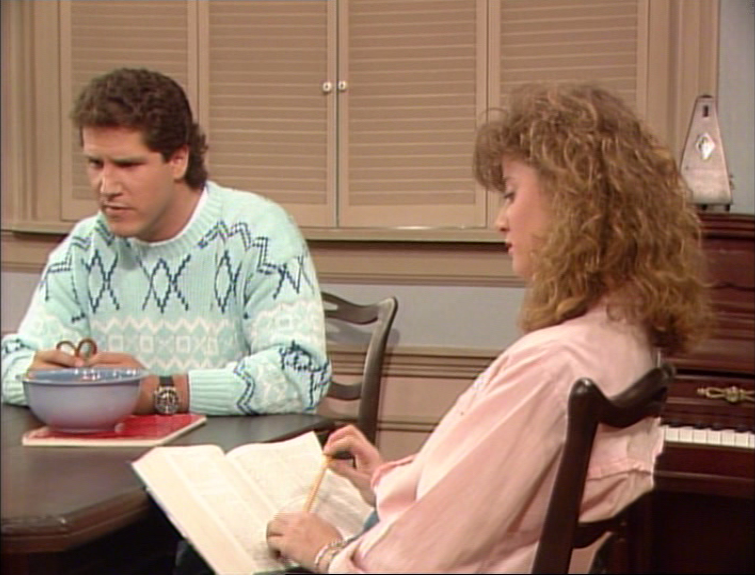

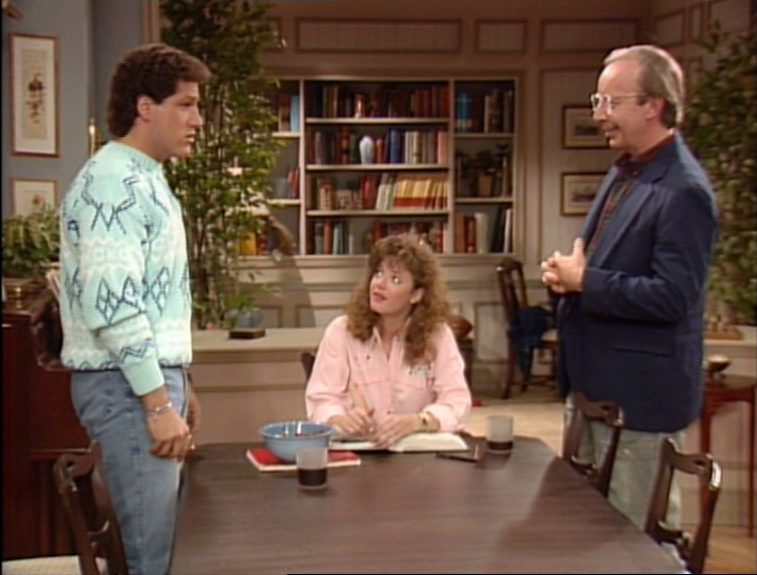

Kate says, “A funeral for ants?”

She looks at him like this.

Then she looks at him like this.

There’s no laughter. I don’t think the writers or editors saw this as a joke. And it’s probably not. It’s just Anne Schedeen being allowed to act again. And compared to the rest of this horse shit it’s glorious. It reminds me of who she used to be, and why she was far and away the highlight of this show.

Instead of violently sodomizing her husband with that broom handle, though, she lets him speak. Willie insists on the funeral, because there can be a good deal of therapeutic value in ritualism, and while his consequent flipping out at ALF is kind of unfunny and dumb, I still like the idea that he’s being a social worker, even if he’s now also being an asshole.

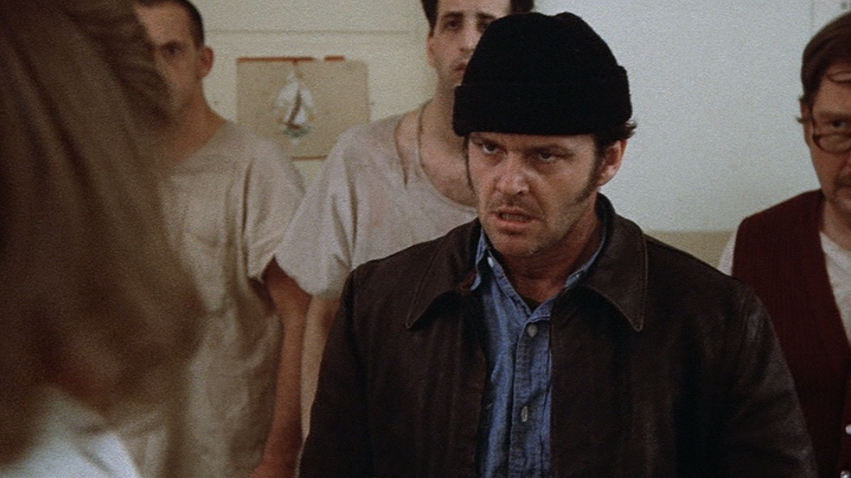

Anyway, the episode is almost over so we get right to the funeral. It’s in the back yard in broad daylight because at this point the family is actively hoping that Mr. Ochmonek sees ALF and burns him to death with his cigar.

We do get a great sight gag at the funeral, though, when Willie lays a wreath near a bunch of popsicle stick tombstones. It’s a legitimately funny moment, even if the screengrab makes it look like Willie is about to take a dump.

Brian asks if he can take his black armband off, and you can hear the stage crew panic because that means they need to pay the kid for a second line this week.

ALF officiates the funeral, which is neither as funny nor as sweet as it could have been. But it’s okay…it’s not overtly idiotic or anything, so I’ll take it. The best part is when he calls on Willie to speak about the ants, and the guy has no idea what to say. At a loss for words he ends up complimenting the ants on their hospitality.

It’s a funny moment, but it loses impact as the same joke is repeated with each member of the family in turn.

Then ALF lists off the names of all the ants, and it takes forever because there were a lot of ants. Ha?

While he recites the list of dead, Kate complains that ants are swarming all over the food they prepared. He says, “They’re mourners, Kate,” and that was actually a really cute little joke to end the sequence.

Sadly it doesn’t end the sequence, and he keeps reading names. Was this episode two minutes short or something? God forbid we spend more time in one of the earlier scenes that were actually good.

Later on ALF eats all the food and says Kate’s potato salad tastes like shit. Then he burps and the episode ends. Wubba lubba dub-dub!

In the short scene before the credits, we find out that ALF wrote to The Morton Downey, Jr. Show. Thank Christ ALF had better sense than to write to his own show’s analog, otherwise we might have had to see that jackass Lenny Scott again.

Anyway, ALF suggested that they add a segment about civil rights for ants. The letter tells him to go fuck himself.

MELMAC FACTS: Orbit gnats were a thing, and they’d get cooked to death by the heat shields on ALF’s space ship.