I mentioned in the first installment of this series that when Mega Man was initially released, there were very few games on the NES worth having. It came out early in the console’s lifespan, after all. Developers were still figuring out what to do with the hardware, and what would appeal to the new generation of gamers. Compared to nearly every other game available at the time, Mega Man was a clear standout and a must have.

Mega Man 5 faced the opposite situation. It was released toward the end of the system’s life. While games were still being manufactured for the NES through 1994, the Super Nintendo was released in 1991. It was another hugely successful console, and gamers flocked to that, leaving the NES largely behind by the release of Mega Man 5 in 1992.

We kept our NESes, of course. We still loved them and still played them. But they already felt obsolete. Whatever trickle of new games came out for the system paled in comparison to the waves of incredible new 16-bit releases for its successor.

I listed the must-have NES games prior to Mega Man way back in that article, so I might as well list the must-have ones post-Mega Man 5: Kirby’s Adventure. Maybe, if I’m feeling generous, Star Tropics II.

That’s all. It may sound like I’m being sarcastic, what with the innumerable great games for Nintendo’s original system, but I’m not. Those games — all of those games, whichever ones you’re thinking of — were already in the past. The NES was slowly and quietly dying, serving as the home of unasked-for sequels, licensed cash-ins, and limp puzzle games. It was over, and Mega Man 5 wasn’t exactly the kind of game that was going to win it any attention back.

One reason the first Mega Man stood out upon its release is that it was like nothing else we had seen. It felt — and I’d argue was — revelatory. It was an exciting new promise of a new kind of game. One in which the very sequence of its levels was left up to the player…a challenging, relentless, rewarding adventure that felt completely unlike anything we had experienced up to that point.

I think you know where I’m going to say Mega Man 5 struggled.

By this point, we knew the formula. Many of us grew tired of it, playing a new Mega Man game every year, wading through whatever the next batch of the levels happened to be, feeling disappointed by the latest cache of weapons.

The promise of a new kind of adventure was gradually replaced by a dawning predictability. By hewing so close to the same formula for so many games in such a short period of time, the Mega Man series robbed itself of its most appealing feature: its uniqueness. As a series, Mega Man was still unlike any other. But with so many games crammed into a narrow release window, that didn’t matter. It overcrowded its own market. And it almost didn’t matter how good the individual games were; the formula now felt old-fashioned. Even stodgy. Capcom convinced its own audience to stop caring.

Mega Man 5 was the last of the games I played until Mega Man 9. That’s right…as much as I loved the series, it’s Mega Man 5 that convinced me to jump ship. I figured it would be just fine without me, and I stopped paying attention. When I saw Mega Man X on the Super Nintendo a year or so later, I thought it was Mega Man 10. I wasn’t being wry; I was fully convinced Capcom could have rushed out 6-9 on the NES in the span of around 12 months without me noticing.

But here’s the thing:

I love Mega Man 5.

At least, I do now. At some point, my response to the game…flipped.

When I played it as a kid, it was at a friend’s house. (His name was Eddie, funnily enough.) I don’t think either he or I were really interested in it. I know we didn’t make it far.

We played a few levels. We tried to figure out how to pronounce “napalm.” (Check your peacetime childhood privilege, boys.) We laughed at the fact that one of the new Robot Masters was a train. Were they that desperate for ideas? Were we really going to spend all weekend squaring off against the iron horse?

We were not. We probably had some degree of fun, but it was less than the fun we could find more easily elsewhere…either on Nintendo’s new hardware, or in Mega Man’s own back catalog. Mega Man 5 was the first title in the series that, to me, didn’t feel like it mattered. And so I only played it once back then. And never again, until around five years ago.

When I loved it.

And that’s the reason I know Capcom hamstrung their own series. It’s not that the games were getting progressively worse, or even less inventive. It’s that, in the words of Artie Fufkin, they oversaturated. They split our attention so finely between the series’ own releases that it was impossible to invest in them anymore.

When I played Mega Man 5 back then, I thought it sucked. What I was really feeling was series fatigue. Coming back to it after a break — with a fresh mind, with more patience, with breathing room the series desperately needed — I found a very enjoyable installment. One that was surprisingly full of ideas. One that deserved the very audience it forcibly pushed away.

Revisiting it for this series, I expected to find more fault in it. I expected to realize that my fondness was really just a kind of relief that wouldn’t hold up under scrutiny. I expected to feel a little embarrassed for enjoying it the way I did when I finally took the time to play it again.

If anything, though, it just reinforced my love for it. I’ll say it right now so you can stop reading, secure in the knowledge that I’m mentally ill: Mega Man 5 is one of my favorites in the series.

Like Mega Man 4, Mega Man 5 attempts a story that’s slightly more involved than “the good robot should kill the bad robots.” The previous game’s use of Dr. Cossack was a relatively inspired one, as we didn’t know that character yet and had no idea what his actual motives would be. We’re told he’s a bad guy, so we go out and fight him. When we later learn he’s a good guy it does qualify as a twist…even if the further twist that Dr. Wily was behind it is dead in the water.

Here we get…well, the same story, sadly. Instead of Dr. Cossack, it’s Proto Man. Or, rather, it seems to be. Positioning Proto Man as the antagonist is fairly inspired, as his allegiances were already hazy when he was introduced in Mega Man 3. Having him rebel against Dr. Light only to, say, change sides again mid-game and help Mega Man take on Dr. Wily would have been a nice arc, if also a predictable one. Instead, Proto Man’s conflicted gun-for-hire nature doesn’t factor into things at all; the bad stuff Proto Man allegedly did was actually the work of an imposter, while Proto Man was…I don’t know. In Fiji or something.

Oh, and Dr. Wily was still behind it. Spoilers for anyone who recently hit their heads, I guess.

Pitting Mega Man against Proto Man on a larger scale certainly seems like the kind of thing the series could have been building toward, but the reveal that Proto Man wasn’t involved at all robs the character of any exploration of what makes him tick and robs the game of any interesting thematic resonance. Mega Man fighting his brother is inherently fascinating, whatever the reason, whatever the outcome. Mega Man fighting Dr. Wily for the fifth time is inherently not.

Of course, story is the least important thing about any Mega Man game, so I can’t hold it against Mega Man 5. It’s just that making Proto Man the villain (even if it’s destined to be a temporary role) suits the unpredictability of his character, and it’s frustrating that the game tip-toed right up to that concept without bothering to actually explore it.

On the whole, the stages in the game are quite good. Not difficult, no, and that can be its own kind of problem, but not every Mega Man game needs to be tough as nails. Also, I’ve replayed each game for this review series, and Mega Man 5 is so far the one that’s come closest to making me run out of lives. Granted, that’s entirely down to my sloppiness in the final fortress, but still…

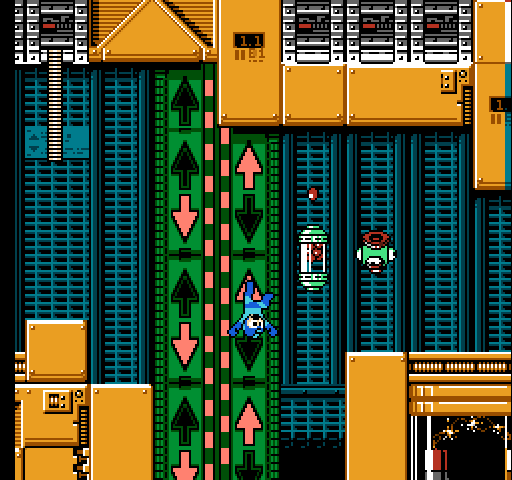

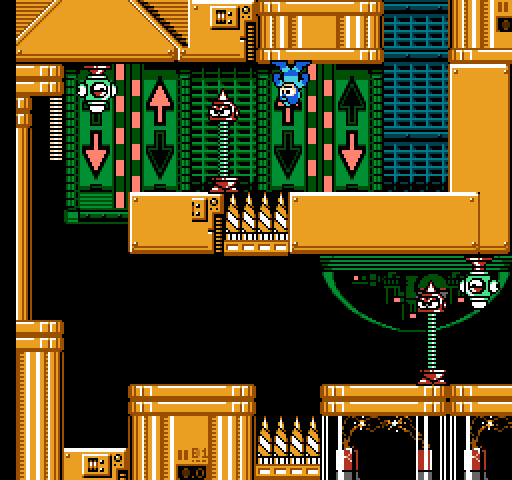

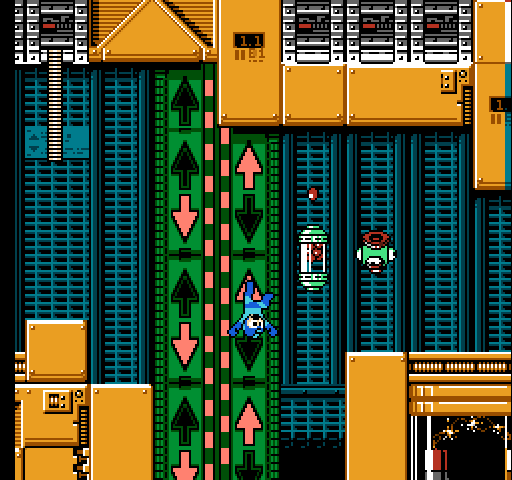

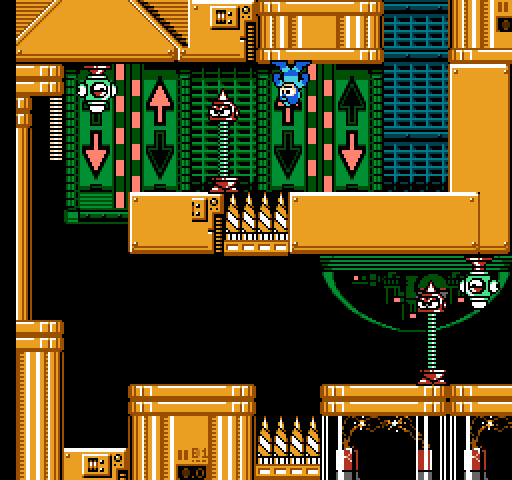

In fact, I’d argue that steep difficulty would actually work against the kinds of things Mega Man 5 wants to achieve. The levels are more gimmicky than what we’ve played in the previous games. Whereas those were meant to be creative gauntlets that at first challenged and then gradually empowered you as a player, Mega Man 5 creates stages that are more like amusement park attractions. Each of the levels actually feels distinct (as opposed to looks or sounds distinct) in ways that most of the levels in the previous games did not.

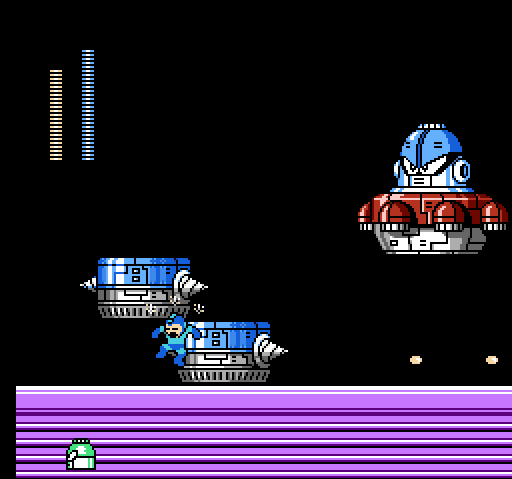

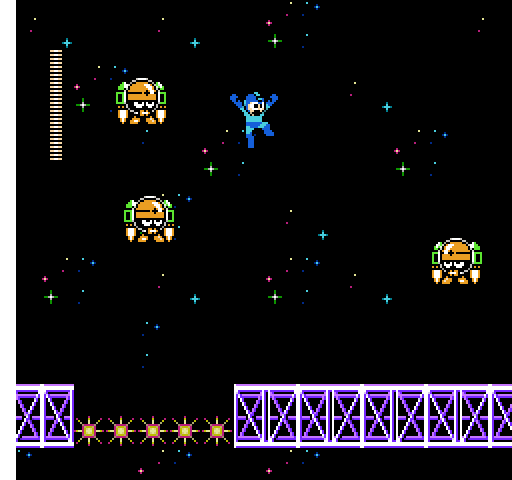

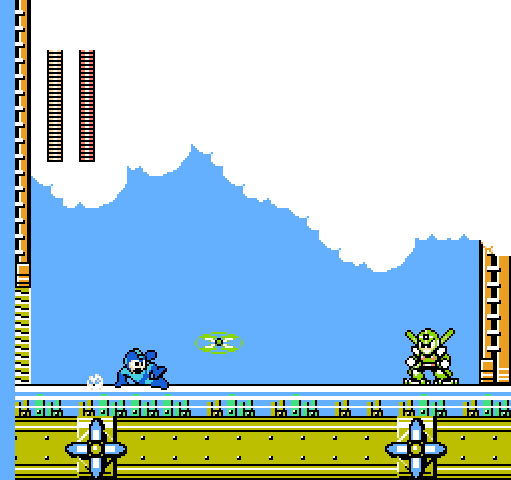

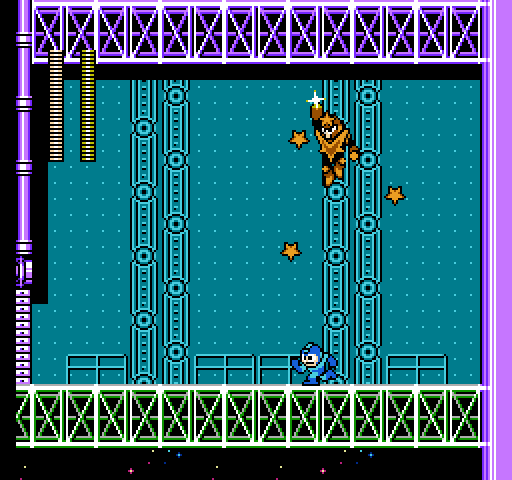

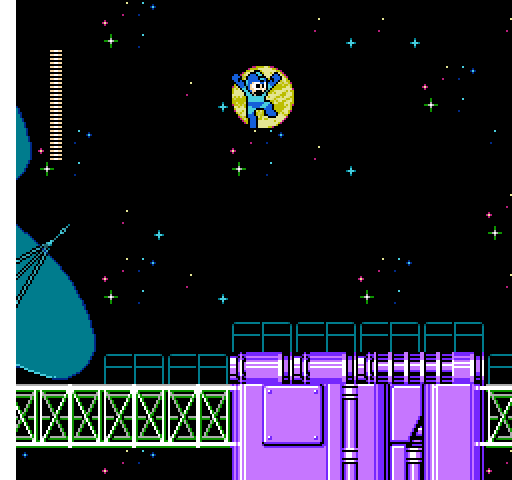

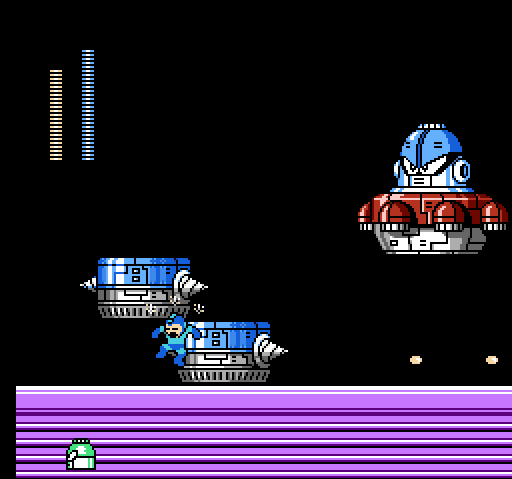

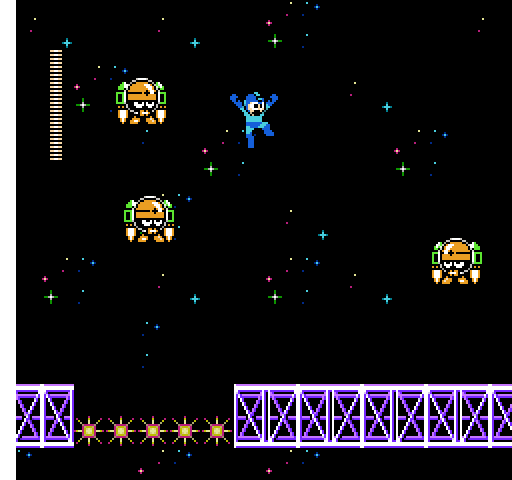

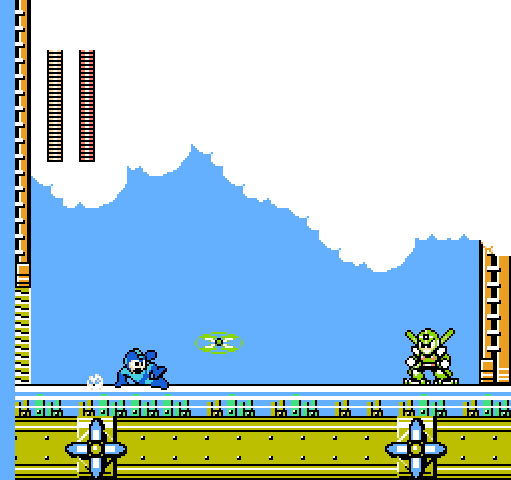

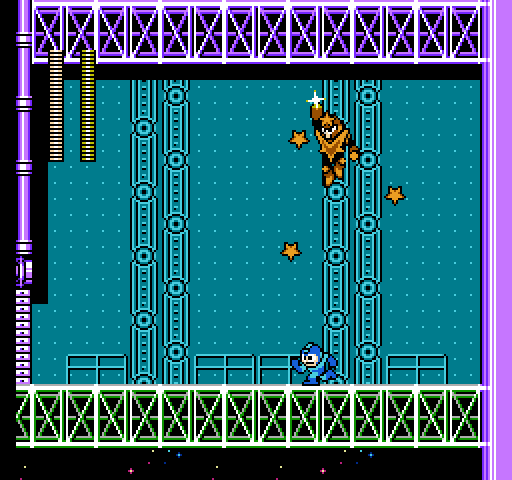

A good example of this is Star Man’s stage, which takes place in outer space. It’s essentially no different than any level that’s used water physics in the past (which, surprisingly, are only the Bubble Man and Dive Man stages), but the fact that there is no water makes it feel unique. Mega Man may control identically in the vacuum of space to how he controls at the bottom of the sea, but the starfield, the space-themed enemies, the meteors raining down from above…all of it works in tandem to trick the mind into believing it’s something fresh and new, and that makes it more fun as a result.

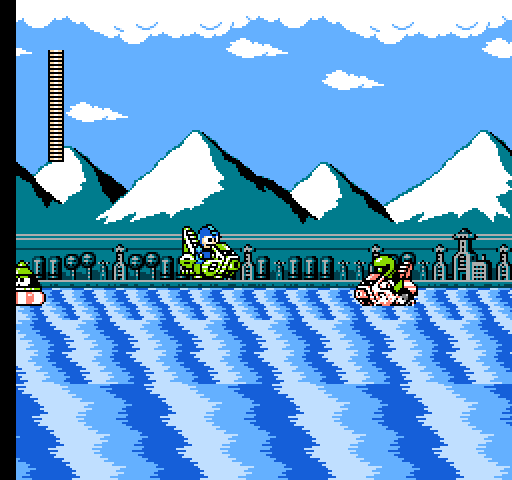

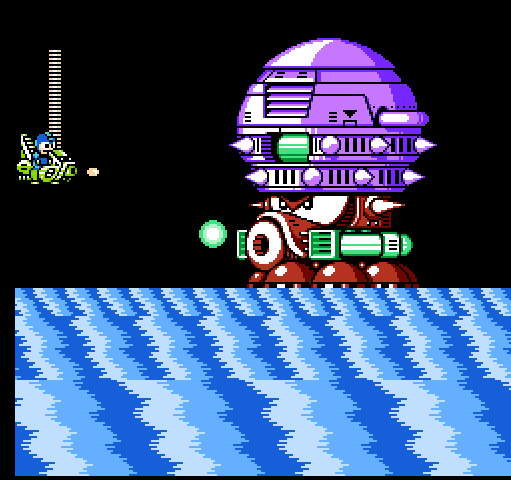

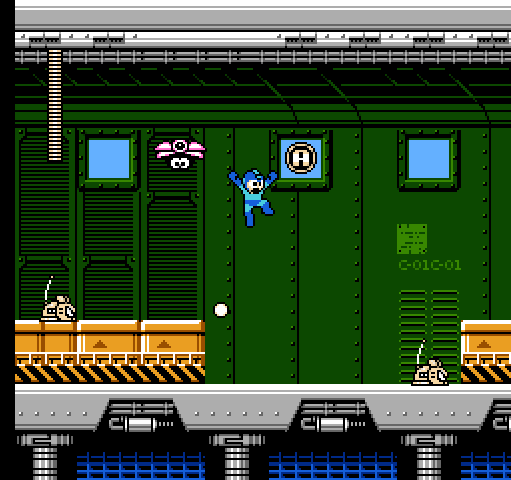

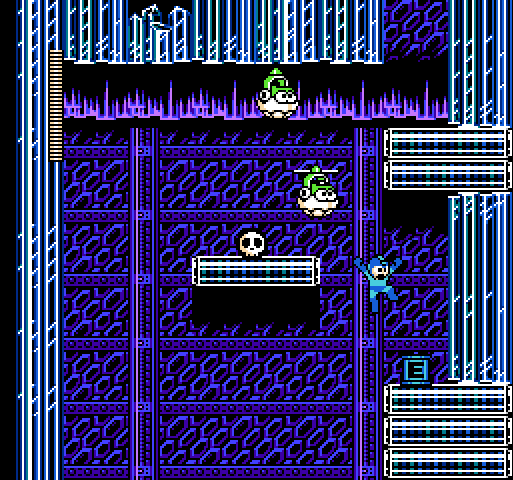

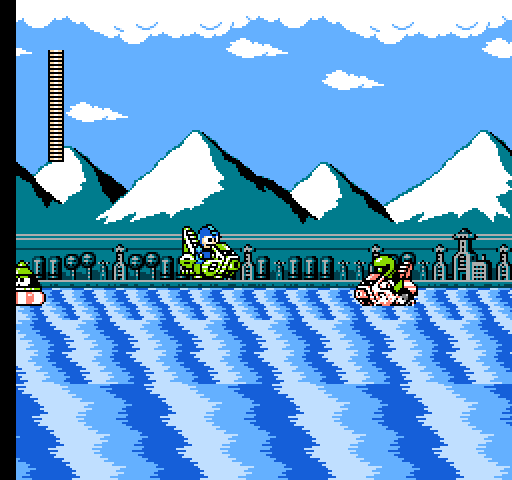

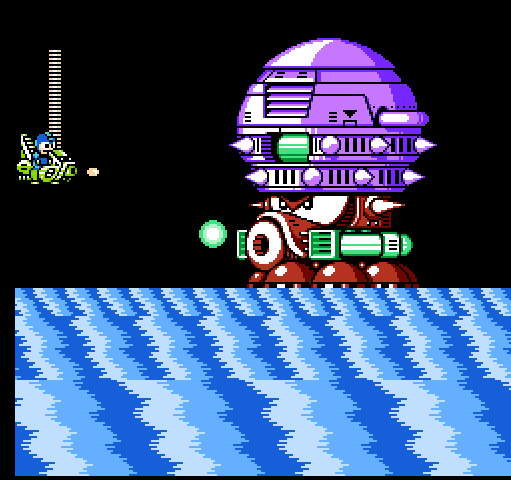

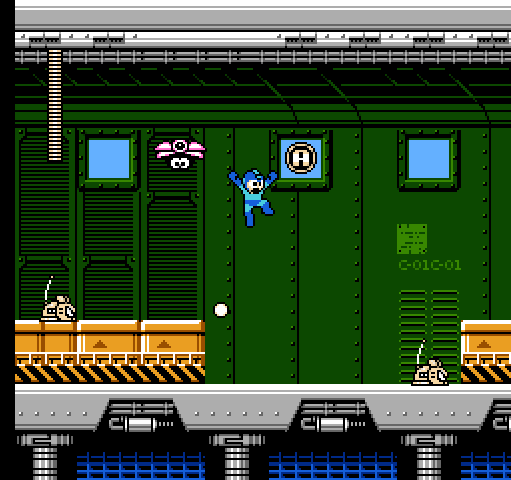

Then there’s Wave Man’s stage, which features no traditional enemies throughout its main stretch, serving as more of a brain teaser in which you steer Mega Man around and through various traps. It lends itself to an almost contemplative approach…which is then shattered impressively when you’re forced to mount a wave bike and fight your way through robot dolphins and a gigantic octopus miniboss.

First there are no enemies, and then there are no traps. First you have all the time in the world for careful consideration, and then you have none.

It’s a stage that seems to fracture the Mega Man experience interestingly, putting all of its traps at one end and all of its speed and urgency at the other, when they’re usually combined. It’s almost disorienting, and it makes you appreciate both halves of the level-design balance, giving you a chance to engage with each of them in turn.

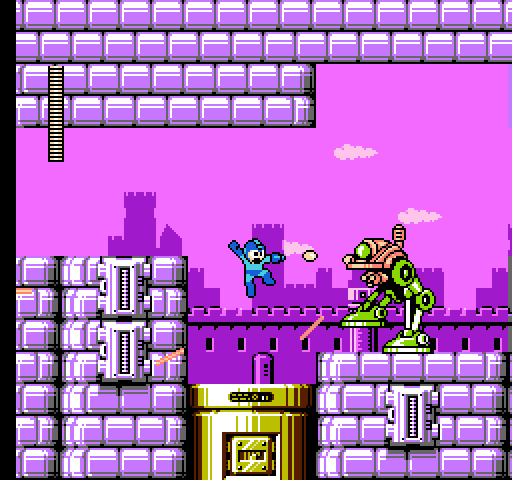

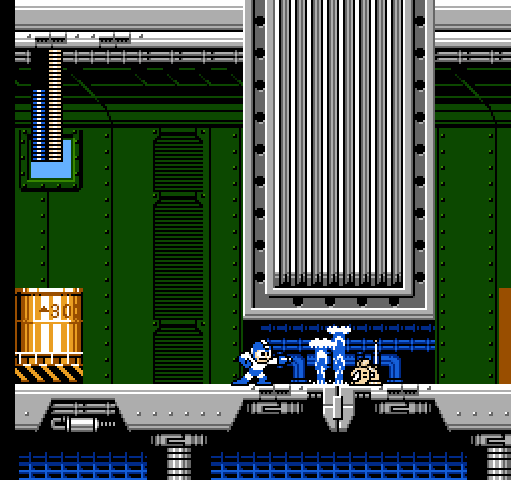

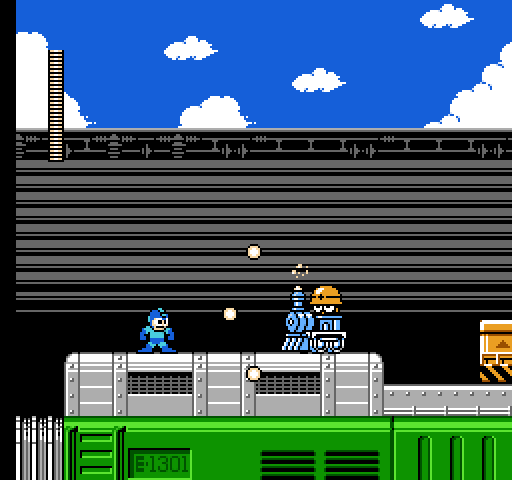

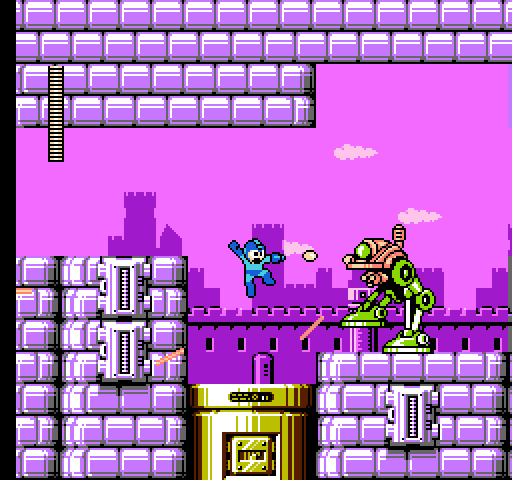

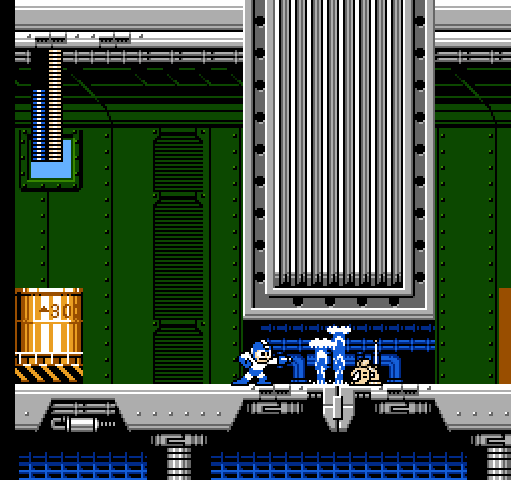

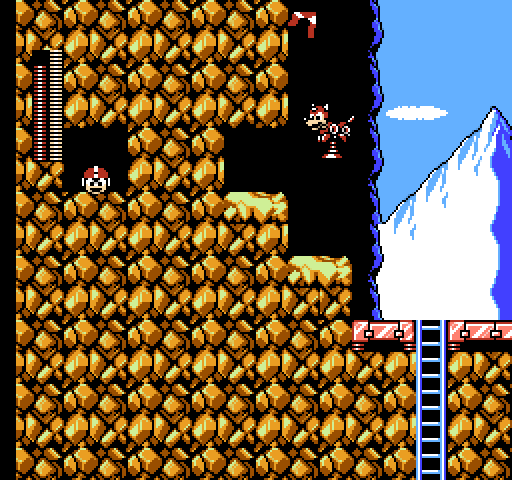

The Charge Man stage is also a highlight, with what has to be the best music in the game. (And if you haven’t stopped reading yet, feel free to stop when I say “…and the music in this game is very, very good.”) It plays much like a standard Mega Man level, but the mere fact that it begins with you boarding a train at the station and then has you climbing into, around, and on top of it as it speeds down the rails gives the entire thing a sense of momentum that most stages lack.

Unlike Wave Man’s wave bike section, it doesn’t force you to move fast and carelessly, but it does subconsciously encourage you to. The scenery flashing by in the background implies a kind of momentum to which you’re likely going to match your own actions, unless you’re aware enough of the effect to proceed with caution. It’s a great trick, and one I’d bet most players who perform poorly in the stage don’t even realize is being played on them.

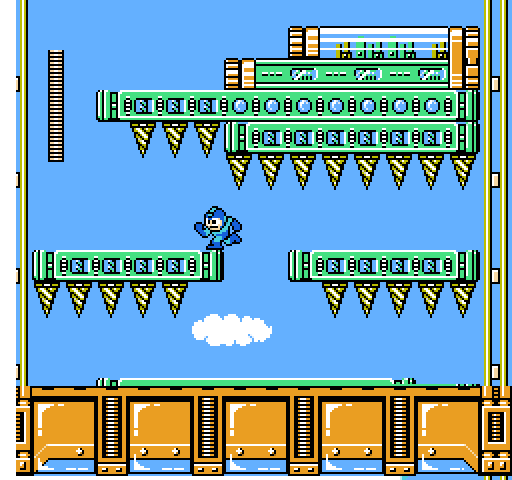

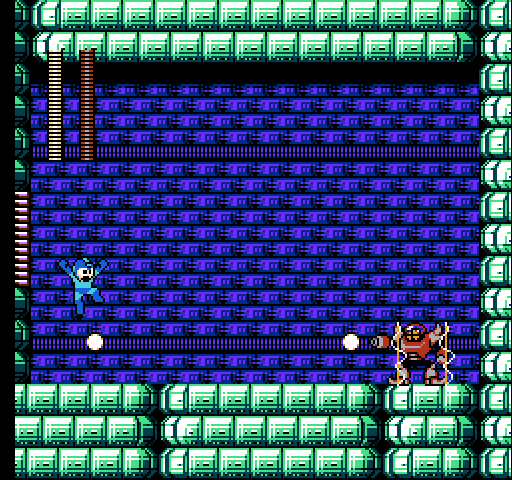

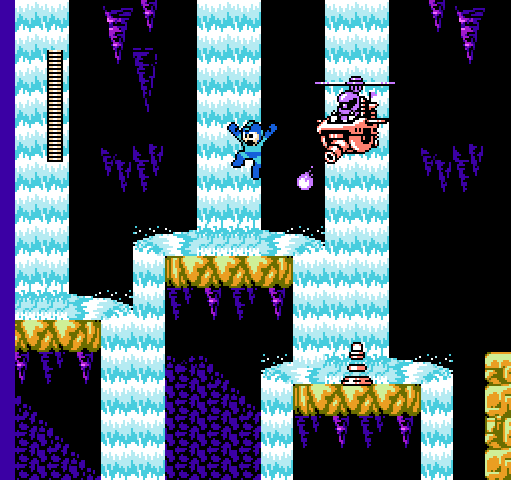

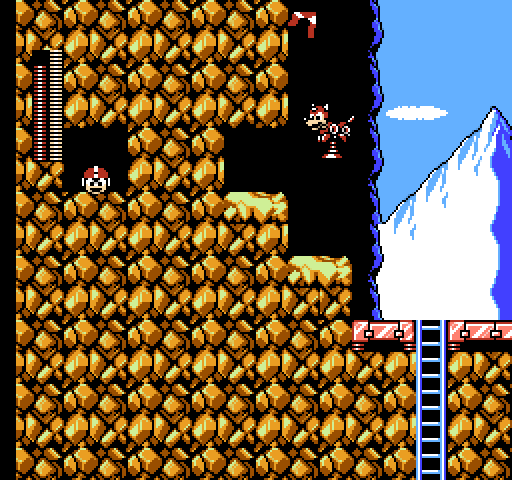

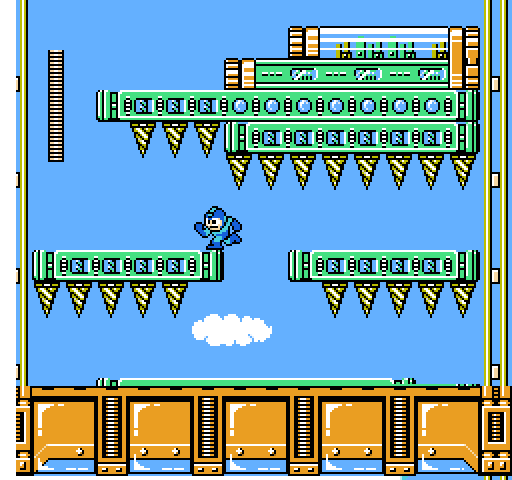

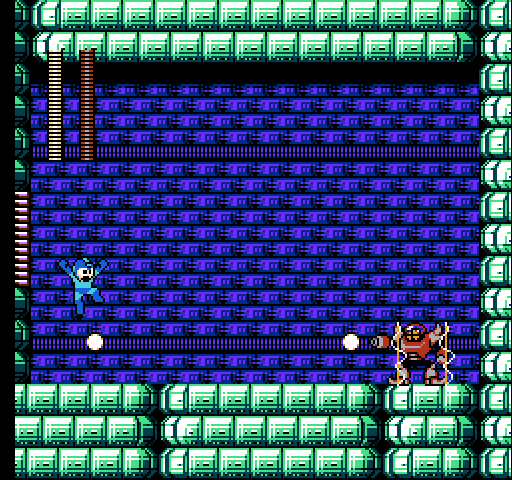

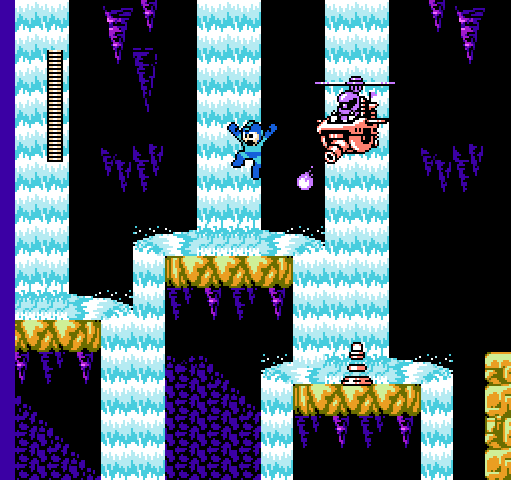

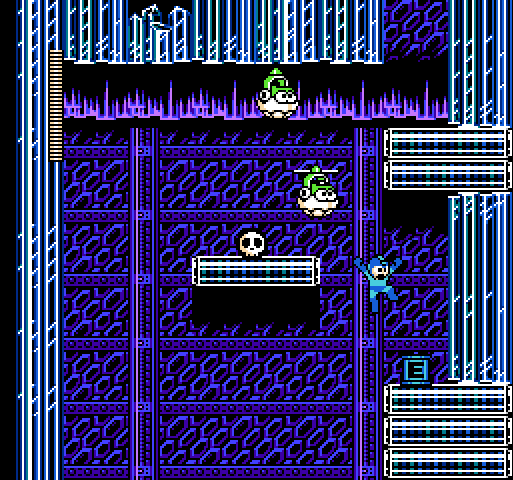

But Gravity Man’s stage is clearly the best, with a truly innovative central mechanic that’s so much fun. It’s more than just a great idea executed well…it’s an absolute delight to play through again and again, and the boss fight — in which the gravity flips constantly and you’re never on the same plane as Gravity Man himself — is a very clever way to see the stage gimmick through to its logical climax.

The sudden shifts in gravity are…well, they’re great, and they make Gravity Man’s stage one of the most memorable in the entire classic series. They also wouldn’t be nearly as fun if the level were more difficult. As it stands, with fairly simple and predictable enemies throughout, players can focus on enjoying themselves, on giving themselves over to the spectacle, on immersing themselves in an experience they can’t get anywhere else. They can have fun. If there were enemies and traps that made progress slow and laborious, it wouldn’t work as well. The gravity switching would be an unwelcome layer of frustration on top of an already challenging experience.

That’s something I think a lot of players miss. They say, “Sure, it was fun, but it was too easy.” What really happened, though, is that Capcom understood something that Super Mario Galaxy would prove it also understood 15 years later: steep challenge interferes with basic thrills. Super Mario Galaxy was an extraordinarily easy game to complete, and yet everybody loves it. Rightly so; it’s a game that deserves to be loved. But I think they loved it because the thrills were accessible. Everybody, no matter their level of experience with games, could enjoy the basic thrill of sweeping Mario around planets in low gravity; they didn’t find themselves dying a thousand times in a row for failing to be precise in their movements or attacks. Enemies put up a fight, but only enough to keep things interesting, and almost never enough to serve as barriers to enjoyment.

Gravity Man’s stage knows that, too. If players are going to enjoy walking on the ceiling and getting Mega Man to behave with vertically inverted controls, the enemies had to let them enjoy it. Just as easily, Capcom could have made Gravity Man’s stage as difficult as Quick Man’s. But would that have made it more fun? If not, then they made the right choice. And I honestly believe that if Gravity Man’s stage — in its entirety, without alteration — appeared in Mega Man 3, for instance, it would be remembered as one of the highlights of the entire NES generation.

Mega Man 5 is a game about fun. It’s a game that encourages fun. In fact, replaying it this time, so soon after Mega Man 4, I was struck by just how sunny and welcoming the entire experience is. It feels like a product of love, or at least one that wants to be loved. It’s the first Mega Man game, I think, that just wants a hug. And, as a result, I was able to enjoy it even more than most of the other games. It’s not challenging, but it’s sweet. It’s not always memorable, but it’s always charming. It’s not the best game in the series, but it might be the friendliest.

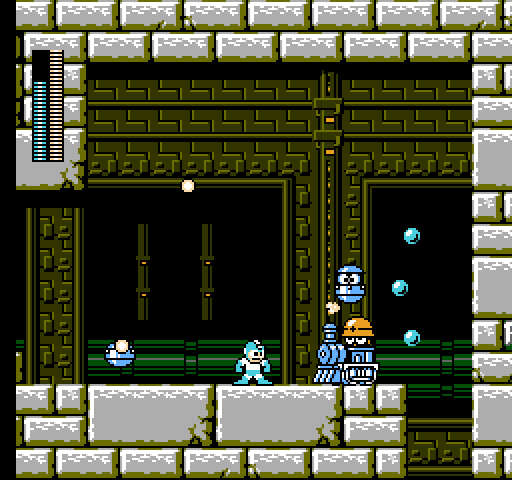

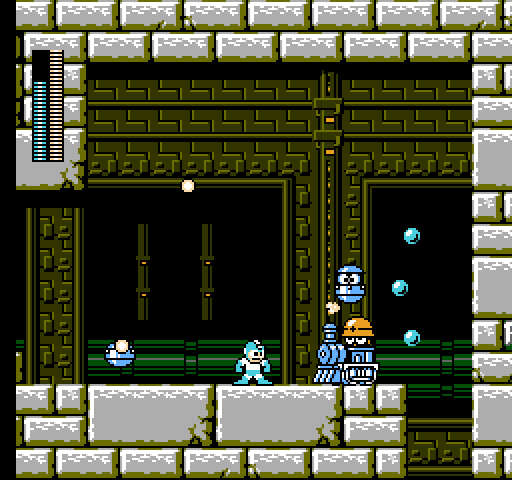

It also introduces a few new ideas to the gameplay, which is nice, even if they’re not anything significant. For starters, there’s Mega Man’s new animal companion, Beat. Like Rush, Beat will show up in future games to help our hero, but unlike Rush, his role is always in flux. Here, for instance, he flies around and pecks at enemies. In Mega Man 7, he doesn’t attack at all, but rather rescues our hero from pits. In Mega Man 8 he adds extra (and optional) firepower during the Rush Jet sections.

Beat’s revolving role is a symptom of the fact that he was introduced to solve a problem the series couldn’t even identify. To put it more flatly, Mega Man 5 introduced him without having any concept of what he’d be good for, and the series has struggled to find a consistent use for him ever since.

With Rush, there was already precedent. The Magnet Beam and Items 1, 2, and 3 all helped Mega Man navigate stages, and there was every indication that future games would require utilities of their own. By introducing a Dynomutt to the Mega Man universe, those utilities would have a recognizable and welcome delivery system.

But Beat here…is just a weapon. Not even a different kind of weapon. He’s essentially a homing projectile, which is nice, but not really striking or important. Beat himself is pretty neat, though. He was allegedly built by Dr. Cossack by way of saying thanks, and his design suggests that Cossack used one of Mega Man’s spare or discarded helmets to build him. That’s a nice detail, and it makes the universe feel that much more cohesive.

Another new gameplay idea comes in the way Mega Man collects Beat: in each of the Robot Master stages, there’s a plate with a letter on it. Together they spell MEGA MAN V, which somehow adds Beat to your inventory. What’s noteworthy about this is that they are the first true collectibles in any Mega Man game.

The Balloon and Wire Adaptor in the previous game don’t quite count, as those are more optional utilities than collectibles, and the letter plates would set a precedent for later games to follow. Bolts are scattered around Mega Man 8 and database CDs are hidden in Mega Man & Bass, for instance.

In all, the letter plates are a nice way to encourage exploration and consideration of how stage elements work. For example, the letter in Gyro Man’s stage requires you to stand still on a platform that you know ahead of time is going to plummet quickly; it’s a decent test of reflexes that works precisely because it asks you to behave counterintuitively. Then there’s the one in Gravity Man’s stage, which requires you to have a working understanding of how Mega Man moves while the gravity flips…as opposed to before or after it happens.

None of these are especially difficult to find — barring the one in Stone Man’s stage, which can’t reasonably be found incidentally — but it’s a first pass at getting players to think about Mega Man stages in a new way, and not just as long corridors between the first screen and the boss room. The plates are interesting for that reason, if for no other.

On the whole, I think the levels are pretty good, and the soundtrack stronger overall than Mega Man 4‘s. Crystal Man and Stone Man are the only ones whose themes aren’t really up to snuff, but the rest — especially Charge Man’s, Napalm Man’s, and Wave Man’s — are among the best tracks you’ll find outside of Mega Man 2 and Mega Man 3.

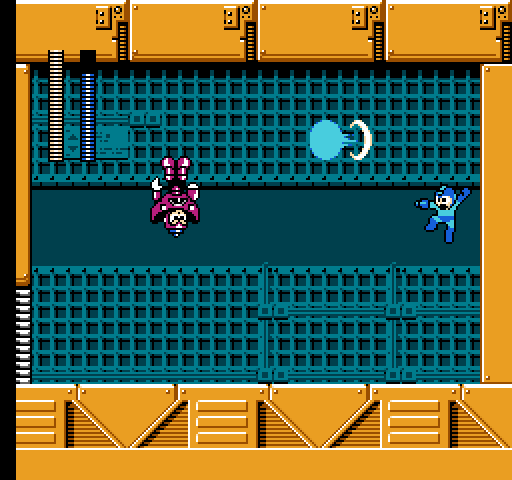

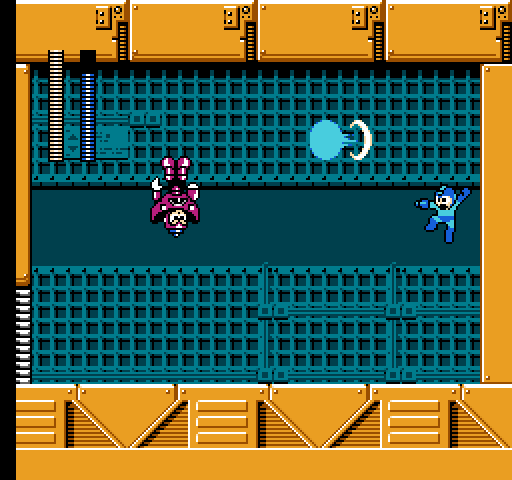

But, of course, the Robot Master fights themselves are pretty uninteresting. The best fight is clearly Gravity Man’s, but beyond that I’d be hard pressed to tell you anything else very impressive.

I do like the concept of Gyro Man flying into cloud cover for much of his fight, but it’s not as interesting as it sounds, and he doesn’t spend his time out of sight doing anything dangerous. He just plops into view or sends some slow projectiles down. It’s about halfway to being a great boss fight, and it never gets there.

Others, like Wave Man, Star Man, and Crystal Man just hop back and forth shooting at you. Stone Man doesn’t even do that much; he usually just hops back and forth. Napalm Man does have a pattern that’s fun to exploit once you understand it. He’s nowhere near as fun to fight as Ring Man, but he makes for a satisfying enough duel in a similar way.

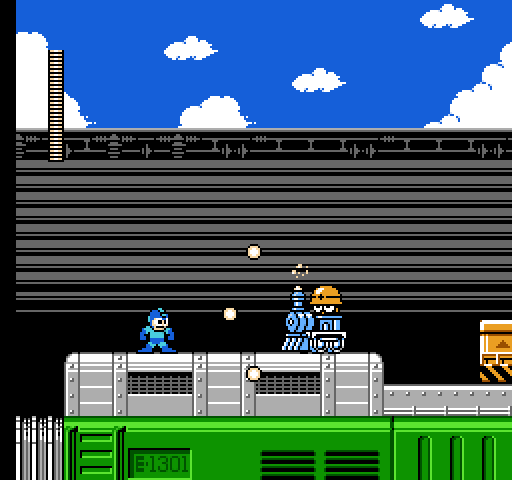

Charge Man at least has a pattern we haven’t seen before, which sees him closing in on Mega Man almost constantly, prioritizing contact damage to take our hero down. That is a nice and unexpected gameplay wrinkle, and it makes sense. All throughout Mega Man history (and nearly all throughout video game history), touching an enemy damages you, and not the enemy. Why, then, do so many enemies keep their distance? Why are none of them interested in simply colliding you to death?

Charge Man is very interested, and it makes for a standout fight with a lot of nice tension. The fact that he’s weak to the game’s crappiest weapon (oh, worthless Power Stone…) means you can’t actually just force your way mindlessly through the fight and miss it; you have to experience Charge Man in all of his frantic, close-quarters glory.

Charge Man is the exception that proves the rule, though, and once you take him out you realize just how incapable the other boss fights are of measuring up to his.

Then there’s the related matter of the Robot Master weapons, which may be the worst batch yet. But here’s the thing: they’re not inherently bad. That is to say, they aren’t bad or dull ideas. (We’ll see plenty of those next time.) They do fall down in the execution, though…mainly because the game doesn’t give them much of a use.

The best weapon is easily the Gyro Attack. It’s a fairly powerful projectile that you can turn 90 degrees once after firing. It’s great for hitting enemies straight ahead, or higher or lower than you’d normally be able to snipe them. Its decent firepower makes it even more worth using, as it’s rare you’ll need more than a few shots to take down any non-boss enemy. It’s a worthy addition to Mega Man’s arsenal. But it’s just about the only one.

The Star Crash is a decent shield weapon, but the problem with that weapon type is that they’re almost always unremarkable. They’re passive, and not exciting to use…barring perhaps one exception in a later game. Here it has a basic and predictable use in absorbing the falling shards in Crystal Man’s stage, but otherwise Mega Man 5 doesn’t have much call for a shield.

This is mainly because it’s more generous than any other game in the series with its health drops. 1-ups and health are handed out like candy, so while a shield could conceivably help you avoid some projectiles or take out small enemies here and there, it’s almost never worth the effort of switching to it. When Mega Man is constantly at or near full health, a shield becomes unnecessary.

Then there’s the Gravity Hold, which is a nice screen-clearance weapon, but, again, nothing particularly exciting. And, once again, Mega Man 5 doesn’t offer much call to use it; the number of crowded screens (therefore ones that could conceivably need clearing) can be counted on one hand.

The Power Stone is…indescribable. It produces three stones that orbit Mega Man and quickly spiral offscreen. Aside from a few times you can hang on a ladder and use it to hit enemies directly above or below, it’s fairly worthless. The stones are also spaced out enough that it’s very difficult to hit a target…even a large one, such as Charge Man. This one is flawed in both concept and execution, making it somewhat unique in this batch, but, once more, Mega Man 5 simply doesn’t create situations that are conducive to using it. You’ll experiment with it, see what it does, and never have a need to load it up again.

If it were powerful (thereby earning its name) the difficulty of actually hitting things with it might make sense; you’d trade off a tricky arc for a great deal of damage. Instead, though, it’s ridiculously weak, making me wonder if the developers were just trying to win a bet that they couldn’t design a weapon with absolutely no redeeming characteristics.

Then we get the four most interesting — and therefore frustrating — weapons in the game. These are the ones that should have been fun to use, and indeed seem tailored to specific situational usefulness…but those are situations Mega Man 5 never bothered to include. The Napalm Bomb drops right to the floor and bounces toward small targets that are almost never there. The Water Wave is a sudden wall of water that seems like it will sweep away enemies and create a handy barricade, but in practice it does neither, and Mega Man’s charged Buster can hit low-to-the-ground enemies anyway.

The Crystal Eye is a large projectile that splits when it hits a wall and ricochets around…but I can’t think of any stages or rooms that are built in any way to take advantage of this. In practice you end up with a bunch of smaller Crystal Eyes bouncing around, possibly colliding with enemies and just as likely not, meaning it’s unquestionably easier to use the default Buster. At least you know where those shots will go. Even the fortress boss that’s weak against the Crystal Eye doesn’t encourage or even allow you to use the weapon’s main functionality; the fight takes place in a room without walls, meaning you can only treat the weapon as a differently shaped Buster shot.

The Charge Kick is a very smart idea — turning Mega Man’s slide into its own weapon — but since it deactivates the Mega Buster it’s often detrimental to equip, and there are very, very few situations in which sauntering up to an enemy and sliding through them is preferable to taking them out easier, more safely, and more quickly from afar.

In truth, it feels as though the special weapons and the stages themselves were designed by two completely different teams. They were each produced under a different kind of design philosophy, and they don’t actually function together at all. Any rare instance in which these weapons do you any good is purely coincidental.

But then there’s an exception: the Super Arrow, which you get along with the Star Crash from Star Man.

The Super Arrow is a lot of fun, and we all know by now how much I like weapons that have multiple purposes. In fact, the Super Arrow is something like an unofficial utility; Mega Man can launch it at enemies, sure, but he can also ride it across a room, and use it to climb walls. It’s one of the rare instances of an item in Mega Man 5 that’s fun to play with. You know. Like some kind of…game.

It’s a shame about the weapons, because in a game that was actually built to showcase them, I think they could have some interesting uses. They seem to be tailored to targets that are at awkward or unexpected angles to the player, so why don’t enemies attack that way very often? Why is it so easy to hit everything with a straight, weak shot? With a weapon that bounces around the screen, why don’t we have even one enemy it’s worth trying to hit from behind?

Even Beat isn’t much fun to experiment with, as you don’t get him until you’ve found all eight letters…meaning you’ve explored just about everything apart from the fortresses. And don’t even get me started on what they did to poor Rush Coil…which is now some kind of…springy pogo-platform? It’s awful, and its absurd visual design just makes it look like Dr. Light drunkenly assembled the robot with the coil on the wrong side.

Oh well. At least it’s still fun to play with Rush. (Enjoy that while you can…)

I know the game is rough. I’m fully aware of it. I’ve probably made more negative comments above than I’ve made positive ones. And they were all deserved. So were the positive ones, I’d argue, but you get my point.

I know Mega Man 5 has a lousy reputation, and I remember being turned off by it firsthand as a kid. I remember playing it and saying, conclusively, “That’s enough Mega Man.” Even Capcom seems uninterested in giving it a second look; when they released the excellent Mega Man Legacy Collection last year, which collects all six of the NES games, they included Robot Masters from each included title on the cover image…except from Mega Man 5, which goes totally unrepresented.

But I love it.

I love its stage gimmicks. I love its Robot Masters, however weak and wimpy they are. I love the promise of its weapons, even if that promise is never achieved. I love navigating platforms with the Super Arrow, simply because it’s more fun than screwing around with the shitty new Rush Coil. I love the music, in particular one of the best ending themes the series has ever had. I love the idea of Proto Man pushing back against the good guys, even if that didn’t actually happen or lead anywhere.

I love Mega Man 5 in spite of its flaws, because so many of those flaws are interesting. They suggest a much better game than what we actually got, I know. But the charm is there. The love is there. The fun is there.

Mega Man 4 is the better game. I’d never claim otherwise. It’s technically superior in every way, barring, perhaps, the soundtrack. But I actually like Mega Man 5 more.

What matters when we play video games is not which ones are “better” than others, in any number of possible regards. What matters is how we feel when we play them. The journeys we take within. The ways in which we respond to the things they do, even if what they do is deeply flawed. What games do right and wrong factor into it of course, but those considerations more steer our opinions than drive them.

Our opinions are born of the fun we have, the excitement we feel, the memories we cherish. Games, after all, are an art, not a science.

Put the same ingredients into the blender 10 times, and you won’t end up with 10 equally appealing results. The Mega Man series is a perfect illustration of that fact.

Last time I offered Mega Man 4 up for critical reappraisal. I wouldn’t do the same for Mega Man 5. It wouldn’t benefit from it. I know that. But I’d still encourage readers out there to give it another shot, on its own merits. You won’t find a critical darling there, but you may find a personal one.

Mega Man 5 is a rickety favorite. One I discounted because of how much it seemed to get wrong…only to return to it as an adult, willing to engage with how much it got right. I love it in its imperfections. And isn’t that what love is? Love isn’t a tacit acknowledgment of everything that something gets right…it’s pushing through the hard times, working through them together, holding fast to what is good.

It’s not the best Mega Man game. Nobody on the planet would say it is.

But engage with it…give it time…look past a few admittedly large issues…and you’ll see one of the most playful, warm, adorably optimistic games in the series.

There’s a diamond in there. You just have to be willing to dig for it.

Best Robot Master: Napalm Man

Best Stage: Gravity Man

Best Weapon: Gyro Attack

Best Theme: Charge Man

Overall Ranking: 2 > 5 > 4 > 3 > 1

(All screenshots courtesy of the excellent Mega Man Network.)