In this section we (and Ned) get not one but two introductions to the current state of Team Zissou, one of which is an elaborately staged — literally, as well as figuratively — tour curated by Steve himself. The other, of course, is one over which he cannot exert such control. As a result we end up with two important perspectives regarding our hero: how he looks to himself, and how he looks to others.

By complete coincidence, I’m currently reading Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea for the first time, and as I write this entry Captain Nemo has just finished giving his own new intake — one of which, amusingly, is also named Ned — a tour of the Nautilus. Whether Steve’s tour of the Belafonte is a deliberate comical undermining of that classic scene is beside the point; either way it serves as a humorous echo of that deeper, more knowledgeable and overall more impressive explanation of the wondrous workings of the vessel around them.

Both Nemo and Steve are willful isolates, and both of them use their ships not primarily to explore the world but to hide from it. But whereas Nemo is prideful and passively enthusiastic about his private accomplishments, Steve can no longer muster up excitement, not even for probably-his-son, and he handwaves equally both any impressive equipment aboard the ship and the state of its disrepair.

Unsurprisingly at this point he also dotes more on his production equipment than his scientific instruments, but even that seems to have lost its luster for him. After all, he has a crew to handle that stuff, and can afford to — interestingly — cameo in his own tour of the ship, fishing idly and remaining totally unengaged with even his own words.

But first, some fantastic film making from Anderson here needs to be addressed. We cut immediately from a quiet, naturalistic scene aboard the dark Belafonte to this clearly artificial and colorful sequence in which Steve Zissou addresses the camera — or is that Ned? More on that shortly… — holding the same model of the ship we saw on his desk earlier, in the film he debuted at Loquasto.

Behind him is an enormous mural of this same ship, and that mural is then backlit, revealing the inner rooms and workings of the Belafonte, and then rises to reveal that those inner rooms and workings are a life-sized, brilliantly constructed dollhouse of a set. The fact that this opaque mural and tellingly exposed set overlap so perfectly that the illusion goes almost unnoticed during the reveal is fantastic.

It can take several viewings to realize what even happened, but once you see it the logistics involved with pulling off a moment like that — physically, without the aid of CGI — will never escape your mind. It’s still, to my mind, Anderson’s most impressive shot, making it his low-key, sombre equivalent of the crop duster swooping down on Cary Grant in North by Northwest. Hitchcock liked to have people being chased…Anderson liked to have people retreating. Both directors lay the artistic groundwork at each of these poles that others could only hope to one day approach.

We get a brief mention of the Belafonte‘s origin (it was a long-range sub hunter during World War II) and how much Steve paid for it ($900,000), but we still don’t have any insight into why he wanted a boat or to become an oceanographer (or documentarian) to begin with. Steve sounds bored, as though he’s more of a tour guide than a team leader and he’s given this superficial spiel dozens of times to increasingly restless school children.

The music here is a reversal of melody from Mark Mothersbaugh’s own “Scrapping and Yelling” theme from The Royal Tenenbaums. It’s reworked slightly, of course, but its origin is clear, and there’s a great feature on the Life Aquatic DVD that has Mothersbaugh playing them side by side. (I can recreate it for you, if you simply click here and then here.)

There’s not much I can do with that information in terms of finding unique insight, but I do think it’s a fun detail, made all the more impressive by the fact that a reversal of Mothersbaugh’s melodies can be just as beautiful as his original compositions. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, losing Mothersbaugh, however it happened, was a genuine blow to Anderson’s films.

We then get a still shot of a framed photograph of Lord Mandrake, who Steve says was his mentor. Steve also says that he’s dead now, and we hear the same sound we’ll later hear when Ned mistakes a sludge tanker for some singing jack-whales.

It’s an interesting juxtaposition, and one it’s impossible to notice the first time through…you need the later point of comparison to understand. The laughter of life, and the deep bellow of death. Ned confuses the two, but what we see here is that it’s not really confusion at all; each applies to all of us equally. First one, and then the other. Both are true. Lord Mandrake is posing for a photograph in his prime, Lord Mandrake is a lost and distant memory. They apply to him equally, and they apply equally to Ned, whose own sludge tanker is somewhere out there already, calling him home.

From the picture of Lord Mandrake the room-by-room tour begins, and in the first room we see that very same picture of Mandrake on the wall. Did you notice that before now? I sure didn’t…it’s just one reason I’m glad I’m doing this series. There’s so much detail layered gorgeously into the film that I might never catch it all if I watched it a thousand more times.

The fact that the same photo is on the wall makes it feel as though Steve is walking Ned through these scenes, pointing things out as he goes. And yet he isn’t. As mentioned earlier, we later see him fishing, apart from and disinterested in his own narration.

This is one of Anderson’s tricks in The Life Aquatic, with which he blurs the line between the film being fiction, and events within the film being fiction. Here the set is clearly false and Steve is addressing the camera, which would seem to suggest that this has been staged for our benefit, rather than for the benefit of any characters in the film. Yet later on Ned and Steve will walk through this very same — and still obviously false — set having an argument, meaning it is real within their world. The subject of the argument? Well, among other things, fiction vs. reality.

Anderson is very clearly toying with our preconceived notions about how films work, here taking his most overtly artificial construction and letting it stand on its own, then later integrating that into the larger world and insisting that it’s real. It lends that later moment a bizarre sense of importance and weight, and raises for us larger questions about the world we’re watching, just as Ned has questions about his own world raised for him. Extra-cinematic tonal resonance.

It’s a pretty great film. Have I said that already?

The only thing we hear about in the first room is the picture of Lord Mandrake, so Steve brings us immediately on to the sauna. The imperfect blue tiling suggests a lack of uniformity — or clarity of vision? — that we’ll see elsewhere on the Belafonte and Pescespada Island…the sense that things have been cobbled together at various points in the team’s history, with little or no attention paid to cohesiveness. It’s a sharp contrast to what we’ll see later with Operation Hennessey.

Very oddly, Steve mentions that he keeps a Swedish masseuse on staff, yet we never see her again in the film. She’s here on camera now, so either she leaves Team Zissou before we actually set sail, or Steve is lying in order to make the ship sound more luxurious than it really is, and her physical appearance here is just another example of why we can’t trust what we see.

It’s also possible that Steve is “reading” from outdated Team Zissou promotional literature, which would also likely have the condensed information about the Belafonte‘s history and wouldn’t have room to get more deeply into it. In other words, Steve’s sales pitch is outdated, and he’s detached enough from reality that he doesn’t even realize it.

We then move on to a room — unidentified — in which Steve claims he does his science projects and experiments and so on. The fact that he can’t identify what they are or where he is says something…the fact that this room is the only one that goes totally unstaffed says even more.

Again we get a shot glimpse of the technology behind Team Zissou, with outdated computers lining one wall. As mentioned in a previous entry, this is all detail that, in another film, could be used to orient us to the time period in which our adventure takes place. In The Life Aquatic, however, it’s used to highlight just how far behind the times Team Zissou is, and that’s something else we’ll have confirmed when we make it to Hennessey’s sealab.

Also note the chemicals bubbling over with nobody in attendance. More ammunition for Team Zissou’s criminal negligence suit against their captain.

We then move on to the kitchen, which contains probably the most technologically advanced equipment on the ship. Vladimir Wolodarsky, the team’s physicist (though we’ll later learn that his experience is limited to the fact that he was a substitute teacher), frosts a birthday cake instead of working in the lab we just saw. We also get an idea of just how much wine Steve needs to feel at home. It’s money that could have been spent stocking — and updating — the lab below.

The research library was assembled by Eleanor, who is the only member of Team Zissou we’ll meet on this tour to keep her back to the camera, perfectly in keeping with the woman who, in our last entry, occupied herself in a roomful of colleagues by playing Solitaire.

Steve gives special notice to his complete first-edition set of The Life Aquatic Companion Series. I can’t be alone in wanting those, but there’s something quite sad about Steve treasuring books that he ostensibly wrote himself. Of course, since we’ll later catch him consulting the volume on Trawlers, Junks and Dinghies in order to identify a far-off ship, I doubt he had much of a hand at all in preparing them.

Also of note is the volume on The Arctic Night-Lights, which is a phenomenon we’ll encounter later in the film, with another nod to Lord Mandrake.

On a personal note, I genuinely wish I could read Tragedy of the Red Octopus. That looks like a good’un.

The only room in which actual work gets done is the editing suite, which Steve mentions exists so they can cut together footage on the fly. We also, however, see cameraman Vikram Ray being instructed on how to deliver an ADR line…keep this in mind, as we hear many times about how Team Zissou simply films what’s really happening, yet we keep catching glimpses of second takes and details being touched up or otherwise altered after the fact. With our fiction vs. reality theme already strongly in mind, it’s going to be important to keep an eye out for that.

Also I do want to say that this scene would be a great time to write a small piece about each member of Steve Zissou’s crew, and I fully intended to do so, but this is already turning out to be a pretty long entry so I’ll have to get to that later.

The observation bubble, which Steve with an uncharacteristic flavor of pride mentions he thought up in a dream, is in use by Bobby Ogata, the team’s frogman. Humorously he’s actually watching another diver* frolicking with a pair of albino dolphins that swim with the ship.

True to its nocturnal origins, the observation bubble is lined with blankets and pillows. In fact, it seems almost designed not for observation, but for returning to that “dream.” It’s cozy, dark, and requires one to lie down. Sleep, or at least relaxation, is strongly suggested as its main intent, and certainly a man whose star has fallen quite as much as Steve’s had would take any opportunity he had to recapture a dream…however hazy it might be by this point.

The engine room is glossed over, as is the fact that the unpaid interns are responsible for repairing it. Steve mentions that he can’t afford to fix the bearing cases. Nor can he afford to fix the ship’s electrical problems. Nor can he afford to finance his own films anymore. Money is another film-long theme, with Steve keen to brush it aside quickly — which both he and the camera do here — as though his problems will solve themselves in time.

We’ll see how well that works out for him.

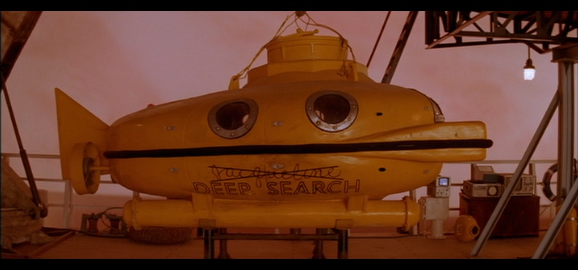

We end the tour on deck, with Steve briefly identifying his submarine, in which the film’s climax will take place, and helicopter, whose disrepair will ultimately kill the man he is currently speaking to.

The submarine is appropriately named Deep Search, with its previous monicker Jacqueline crossed out above it. (I guess Steve can’t afford yellow paint, either.) Ned’s voice asks what happened to Jacqueline, and Steve replies that she didn’t really love him. The submarine was named after a woman in Steve’s life who is no longer in the picture, and we’ll discuss the payoff the name-change later on, when Steve shows off his similarly altered tattoo.

So that’s Eleanor, Mandeeza, Catherine Plimpton and now Jacqueline, and we’re only sixteen minutes into the film. We’ll shortly learn about a 15 year old girl Steve hit on at a French disco. Captain Zissou’s had a busy love life, and, it’s important to note, none of it actually lasts.

It’s also worth noting that Jacqueline is the feminine form of Jacques, as in Jacques Cousteau, an obvious influence for Steve both in and outside of the reality of the film.

Darkness falls on Steve’s fantasy tour — at precisely the moment Steve acknowledges a darkness of his own — and we find ourselves back in reality. We are at the Explorers Club, and in sharp contrast to the Team Zissou uniform Steve was wearing in the previous scene, we see that he’s actually still wearing his suit from last night, wrinkled and disheveled with an undone bowtie around his neck, making it clear that he never changed out of it when he went to bed. Ned, on the other hand, is neatly pressed and presentable. It’s obvious that one of them sees this experience as more of an honor than the other.

Ned also respectfully removes his hat when indoors. Steve, unsurprisingly by this point, does not.

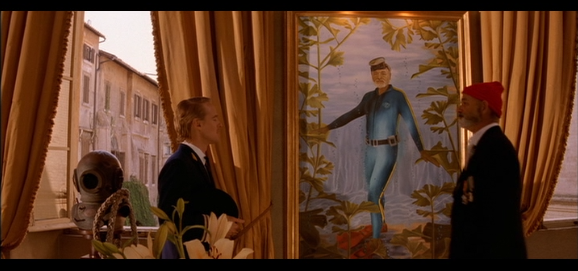

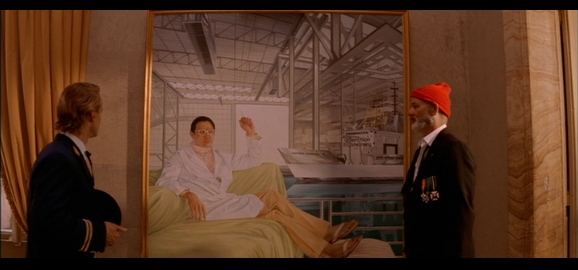

Both men find themselves staring at paintings of their father figures, another passive mirroring that I think reinforces the idea that they are, in fact, father and son. Steve stares at a painting of Lord Mandrake, and Ned lingers on a painting of Steve, which he calls “very lifelike,” despite the fact that the graceful demeanor of the man in the painting is nothing at all like the unwound and directionless man beside him.

When Ned says it’s “very lifelike,” it means two things: it’s life-like, in the sense that it’s like the real thing but perhaps not quite accurate, and also that it’s true to his image of Steve, the one he grew up with, the one he watched on television and read about in books and wrote letters to. The real Steve has yet to supplant this ideal in Ned’s mind, however clear the disparity might be to us.

This is why Ned functions as Steve’s Ghost of Christmas Past. He remembers Steve as he once was…in his prime, in his youth, in his glory. He brings with him visions of happier times, of success and adoration.

When Eleanor asks Steve later why he wants Ned to join the crew, Steve replies, “Because he looks up to me.” This implies, I think correctly, that nobody else does. Ned is a precious resource, and Steve cannot afford to lose that. He’s his last tie — a living tie — to the past…to a seed sown when he was at his best.

It’s his last chance to harvest something he can be proud of, and it’s why he so immediately becomes concerned with Ned and Jane mingling, as Jane is his Ghost of Christmas Present, and the last thing he needs is his idealistic past being tarnished by an intrusion from present-day disappointment.

Also, Steve’s red cap and white beard make him look kinda like Santa. Happy December, everybody!

We then pass a model of Operation Hennessey’s sleeker, cleaner ship, and arrive at a painting of Steve’s nemesis. We don’t learn much about Captain Hennessey here that we didn’t know, but it’s interesting to note that we will later see this man dressed in the same way and draped across the same couch, as though this painting really did capture him for who he is. While we see Steve in his diving gear later as well, we never see him in such a calm, easy state of mind. It shows how much he’s drifted, perhaps, from when it was painted, and may indicate why he’s so uncomfortable looking at that reflected echo of his old self.

Steve then discusses with Ned the possibility of a name change: Ned Plimpton, if he would like, can change his name to Ned Zissou. Unless he also wants to change his first name to Kingsley, which is what Steve would have chosen for him.

As we’ve seen earlier in Steve’s introduction to himself and his ship, and in other cases as well, Captain Zissou needs to be in control. Here, on the first morning after meeting his son, he’s already assuming that control. While the name change begins as a suggestion, and Steve seems to accept Ned’s polite refusal, it later becomes forced on the boy, when the correspondence stock arrives we see that Steve made it out to Kingsley Zissou. Our good captain also demands that the waiter pour the wine for him to sample, as Ned “doesn’t know anything about wine.”

We’ll get into Steve’s insistent need for control later, but for now I want to draw attention to an interesting jump cut here. We go from the waiter pouring wine to Steve downing a glass, with a few seconds of footage snipped out.

I don’t know what to call these cuts, but I love them, and Anderson’s used them a few other times. In The Royal Tenenbaums we cut from Royal insisting to see Richie in the hospital to turning around and leaving because the porter has turned up to throw him out. In The Darjeeling Limited we cut from Peter producing a painkiller to slamming it back immediately. And later in this very film we’ll cut from Ned taking the hand of a fallen Steve to Steve being instantly back on his feet.

I like these. By trimming just a second or two of dead space Anderson creates an impact for moments that might not seem as urgent otherwise.

Steve then overhears some other members of the club discussing his failures, and this is the second introduction to Team Zissou for Ned…and also the one Steve doesn’t have control over. This is his present seeping into and poisoning his past, and he doesn’t like it. For now Ned has the strength to overcome these influences, and even to fight back against them, but as the film progresses and Steve dismantles piece by piece all of the respect the boy still has for him, Ned will become aware of the reality at play here, and cease to see Steve as an idol.

I also want to talk a bit, perhaps oddly, about the astronaut in the background here. Or, rather, the astronaut is reminding me to talk about The Life Aquatic as a work of passive science fiction. Perhaps I’ll be able to say more about that in a future piece, but I find it interesting that Anderson seems to conjure up images of outer space when building out his movie about aquatic exploration.

After all, his choices of Bowie songs lean heavily toward science-fiction conceits: “Starman,” “Ziggy Stardust,” “Life on Mars?” and, of course, “Space Oddity.” We also have “30 Century Man” by Scott Walker used at a pivotal point on the soundtrack, and now the astronaut here is given an association with oceanographic explorers. Deep space and the deep sea…aliens and mythical sea creatures…above and below. Each unknowable and treacherous in its own way, each requiring safety gear and breathing apparatae, each, essentially, an escape from our own element.

It’s interesting.

This is the first time Steve responds to a criticism about his wardrobe by removing the object being ridiculed. Here, it is his earring. Later it will be his red cap, after Jane refers to it as “contrived.” Public perception of his persona is of paramount importance for Steve, but rather than live up to his image, he’s sought instead to shut it out and isolate from it. The moment outside words reach his ears — whether following the debut of his latest film, here in the Explorers Club, or later in an article about himself, it cuts to the quick. Steve doesn’t know how to handle criticism…he only knows how to hide from it.

As before, Steve’s response to this criticism is to flee to safety. After Loquasto, he fled to his ship. Now he will flee to his compound on Pescespada Island, and he wants Ned to come along. After all, Ned just picked him up when he was feeling down…but perhaps more importantly, Ned took his side. Steve threw something away, and Ned picked it up for him. Steve fell apart, and Ned put him back together.

That’s exactly what Steve wants for Team Zissou.

However, this leads to I think a pretty valid question. Earlier, we arrived midway through a conversation between Steve and Eleanor. Steve was making a case for Ned joining them, which Eleanor ultimately accepted.

But in what sense were they discussing Ned joining them? Here Steve invites him to Pescespada Island for the first time, and there are some logistics to work out suggesting that the topic has not been raised before. And later Eleanor tries to dissuade Steve from letting Ned come aboard for their next journey.

So what, exactly, were Steve and Eleanor talking about earlier?

It’s just one question that remains unanswered as Steve acts on yet another opportunity to isolate from the cruel people who speak honestly about the things he’s actually said and done. Only this time he’s taking something with him: physical proof that at one time, he created somebody — biologically or otherwise — who could look up to him.

What’s more, Ned speaking about the mother he lost overlaps with Steve speaking about his dead best friend. Each of them have an opening in their lives. For better or for worse, they choose to fill it with each other.

Next: A God damned tearjerker.

—–

* Another thing I only noticed while putting this essay together: every current member of Team Zissou is accounted for during the ship’s tour, and each of them are clearly visible going about their duties. So who is this helmeted diver? By process of elimination, it’s Esteban. This is something I was only able to determine after the scene ended, and once you realize this is an unspoken cameo by Steve’s departed friend — swimming silently in the water that is now his grave — it’s actually a quite chilling touch. It also, of course, speaks once more to this “footage” being outdated. Better days. Only slightly, but already behind him…

That observation about the diver being Esteban is fantastic. Though I did notice you said “but there’s something quite sad about Steve treasuring books that he ostensibly wrote himself.” But the covers of the life aquatic companion series books all say “by Eleanor Zissou”. They would be fantastic props to own, but I’ve got my heart set on the posters the old man is having Steve sign at the festival.