Joe Dassin, “Les Champs-Élysées”

Les Champs-Élysées, 1969

As in the case of the Reader Mail feature from Monday, Compare & Contrast is something I’d like to do periodically on this blog, and I have a good number of things I’d like to eventually write about in this fashion. But now, since it’s Wes Anderson month, and since my girlfriend and I just rewatched Bottle Rocket, I thought this might be a great time to introduce it.

After all, for the first time, I think I’ve figured out just why that film’s handling of the central romantic relationship rubs me the wrong way. It also made me think about a pretty similar corollary in The Darjeeling Limited, which I think handles the same material far more impressively, and retroactively sheds some light on what Bottle Rocket did wrong.

In both cases a well-enough-off American man seduces a young woman of differing cultural heritage. In both cases the men are guests at their places of employment, and the women are employed to keep them comfortable.

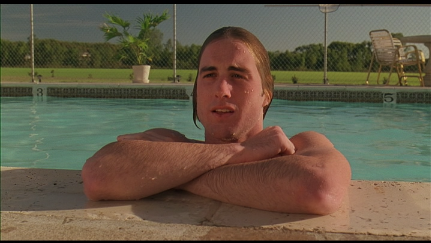

In Bottle Rocket, the American man is Anthony Adams, played by Luke Wilson. Anthony is staying at a motel with two of his friends when he first sets eyes on the woman, a housekeeper named Inez.

He doesn’t speak to her, but he follows her with his eyes, and his facial expression (alongside the tellingly infatuated camera work) makes clear that he feels something for her. On the surface however, there’s no real way to separate whatever he thinks he feels from simple lust.

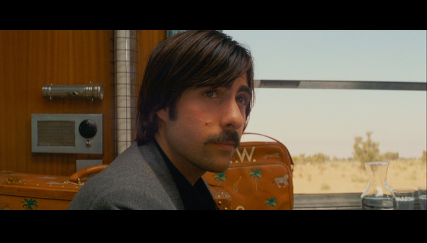

In The Darjeeling Limited, the American man is Jack Whitman, played by Jason Schwartzman. Jack is traveling by train with his two brothers when he first sets eyes on the woman, a stewardess named Rita.

Rita appears with snacks and drinks for the brothers, and, as such, Jack does engage her directly as part of their first meeting. Compared to Anthony, he is taking an active role, and not simply staring at her from afar (it also helps that Rita is aware of both his presence, and his gaze).

Rita, in contrast to Inez, is a known quantity. Jack knows at least something about her, which makes his feelings — more on what feelings those are in a moment — more understandable than those of Anthony, who doesn’t even know what Inez sounds like…he can only know that he likes the way she looks.

Jack also much more openly has hunger in his eyes. Rita offers him savory snacks and sweet lime, but it’s an unspoken third option that he seizes immediately upon. Jack, in a word, is predatory. So is Anthony. The major difference here, however, is that The Darjeeling Limited is aware of the decidedly un-savory nature of Jack’s motives, while Bottle Rocket remains naive. As a result, it’s Bottle Rocket that fails to handle the situation maturely…something that ties at least somewhat into Anthony’s character, but also would have benefited greatly from some larger, film-wide acknowledgment that we’re not supposed to agree with his actions.

Instead, we have the romance playing out successfully, which indicates that Anderson didn’t quite understand how problematic the situation actually is. Anthony essentially stalks Inez, and his overtures to her don’t sound as innocent as he certainly thinks they do. In fact, they belie a predatory mentality that Anthony wouldn’t recognize in himself, in spite of the fact that he goes about trailing Inez, forcing himself into her routine and even ignoring her instructions not to follow her into a guest’s room. Anthony is essentially courting Inez in such a way that in reality would have had the police — or at least a motel security guard — called on him.

In Jack’s case, he is more aware of the lustful nature of his attraction, and even proclaims to his brothers his intentions to sleep with her. Jack Whitman is under no delusions about what he wants, and he makes no secret of it. His courtship of Rita is as accelerated and urgent as Anthony’s, but whereas Anthony believed he was in love and followed Inez around to prove it, Jack just wanted to fuck, and beckoned to Rita to follow him down.

So far, so fair. After all, different characters might feel different things, and they should certainly be going about achieving their goals in different ways. But there’s one thing we haven’t discussed yet, and it’s a big one: the language barrier.

This is where the major difference comes to light: Inez does not speak English. Or, at least, not very well. She doesn’t understand most of what Anthony is saying to her, and while that’s certainly a humorous situation as he knowingly engages her in conversation anyway, it leads to a somewhat unsettling feeling when the topics turn more serious, and we have no reason to believe that Inez understands what they’re even discussing, at least not without an interpreter. One is fortunately on hand in the form of a dishwasher named Rocky, but he is notably not present for most of Anthony and Inez’s conversations.

The advantage here is firmly on Anthony’s side. He is the one with the money, and Inez is there to help. They’re both sharing the same space, but if Inez upsets him — or any guest — she is liable to lose her job, and be replaced rather easily. Anthony has no such fears or cause for concern. It’s notable that Anthony is even more ignorant of Spanish than Inez is of English, but that need not trouble him, as she barely says anything to him in return.

This should speak pretty loudly to Anthony — and to Anderson — that Inez is not interested at best, and fearful and intimidated at worst. At one point in the film Anthony takes a small picture from Inez and, assuming it’s her, asks to keep it. It’s actually a picture of her sister that she keeps in a locket that she wears at all times. Anthony asks if he can have it anyway, and she agrees…though there’s really no reason for us to assume that she understands the question. This American man who has followed her around all day and interfered with her job has now taken from her an item of immense sentimental value. At this early stage in his directorial career, Anderson doesn’t see that that might be illustrating something other than love.

Jack, on the other hand, has no such difficulty communicating with Rita. She speaks his language, and his lack of interest in hers is a theme that The Darjeeling Limited explores in many ways across all brothers. It’s not shrugged off as Bottle Rocket allows Anthony’s to be; it’s a symptom of who Jack Whitman is, and the film doesn’t endorse his viewpoint.

When Jack engages with Rita, he does so as one adult human being to another. He is fully aware of her station in his life — and in life in general — and it’s clear that he does not consider her to be his equal (another theme explored by the film later on). He will say nice things to her and treat her well in an attempt to win her physical favors…but beyond that, there is nothing. He pretends that there is not a clear imbalance of power in their dynamic, but you can be certain he hasn’t forgotten it.

Jack’s courtship of Rita is no more or less hollow than Anthony’s of Inez. They’re exactly the same in terms of what they want — if not what they think they want — and they’re executed in similarly despicable ways. The difference is that Jack is aware of his inherent womanizing, and simply dresses it up in a nice suit when it goes out to play. Anthony is not aware of what he’s doing, and, as we’ll see in a moment, neither is Anderson.

In each case, the elaborate seduction plot is a success. Both Anthony and Jack bed their respective sirens of the service industry, but the difference is that in Jack’s case, it makes some sort of logical sense; Rita behaves in some understandable, identifiable way. In Anthony’s case, Inez falls for him because the script requires her to do so, and what we see next is less an organic unfolding of a new relationship than it is a forced plot point without any clear connection to what we’ve seen before.

Early on, Inez is reluctant even to share the same physical space with Anthony. She’s rightfully concerned about this strange man who keeps plying her with words she can’t understand and refusing to leave her alone. She is uneasy and nervous around him, and all of that is perfectly fitting for the situation at hand. I would never argue that a capable artist can’t turn this, eventually, into a sort of complicated romance, but first the artist would need to be aware of how incompatible it is with such a traditional outcome. Instead, Anderson has Inez fall for Anthony as well, simply because she has to, in the small space of time it takes his friend Dignan to get a haircut.

She still can’t speak his language and it was only a matter of hours prior that his relentless hounding was both terrifying and unwelcome to her, but now she embraces him and kisses him in the swimming pool, because it makes for an admittedly nice image and that’s what the script told her to do. In an unintentional bit of artistic racism, Inez’s character doesn’t actually get to be portrayed like a human being with thoughts and feelings of her own.

By contrast, Rita in The Darjeeling Limited does not undergo the immediate magic of a script that needs a love scene. She does succumb to Jack, but she does so in a way that suggests that this is nothing new. Rich Americans come through here all the time, and this is just one way of coping with the endless stream. In fact, her physical engagement with Jack may well be as much a game for her as it is for him, and though he does selfishly interfere as she’s trying to do her job, as did Anthony, Rita is able to stand her ground and tell him to back off. That Jack doesn’t oblige shows us two things: that he knows what he’s doing, and that Anderson knows what he’s doing.

Rita, likewise, is not romanticized by camera angles and soft focus. Jack catches her in unflattering situations, such as when she’s smoking a cigarette through an open window. Rita is treated like a human being by the film, rather than as some heavenly agent of wish-fulfillment that doesn’t need a personality of its own. She can stand up to Jack, she can stand up to her boyfriend, and she can make her own decisions. Eventually she even has the strength to call Jack on his bullshit. That one of her decisions is to sleep with him anyway may well reflect poorly on her, but it at least does not reflect inhumanly on her.

The actual sex scenes as well as also ripe for comparison. In the case of Bottle Rocket, Anthony trots romantically around in search of Inez, whom he finds cleaning a vacant room, because she’s a minority and that’s what they do when they’re not washing dishes. She obligingly lays down and undresses, the strains of “Alone Again Or” by Love fills the air, and the two unlikely (and unrealistic) love birds smile like children and enjoy each other beneath an artfully fluttering sheet. In short, it’s exactly what Max Fischer imagined a night with Miss Cross would be like in Rushmore…before she dashed his naive and idealized view of sex. As lovely as this scene is out of context, it doesn’t fit into the actual flow or characterization of anything we’ve seen before, and, as such, it just makes it seem as though Anderson still had some growing up to do.

He’s certainly grown up by the time of The Darjeeling Limited, as Jack’s sex with Rita is raw, impersonal, and not romanticized in the slightest. The two don’t even bother to disrobe, the only soundtrack is the train rattling noisily around them, and any possibility of romance is dashed by Jack’s abrupt digital penetration and Rita’s instructions not to cum inside of her.

It’s not romantic, and it’s certainly not sexy. But Jack and Rita don’t want romance, and they don’t care if they’re sexy. They want to have sex, and they have neither the time nor interest to make it anything more meaningful. When Anthony beds Inez, the movie presents it to us as a grand, triumphant moment for both of them. When Jack takes Rita against the wall of a moving train, the movie presents it to us as something that happened. And that’s okay, because when two strangers have sex, that’s all that it is.

That might sound like a kind of cheap way to put it, but not if you’ve ever fucked before it isn’t.

In other words, the big difference between these two films is that The Darjeeling Limited is aware of what’s happening, and presents it realistically. Bottle Rocket is not at all aware of what’s happening, and so is able to present it in a much more romanticized light. The latter sounds appealing, but it serves as a barricade for the audience. The former they can believe in, but the latter seems to exist somewhere without them, separate — and notably so — from how they could have reasonably expected these events to transpire.

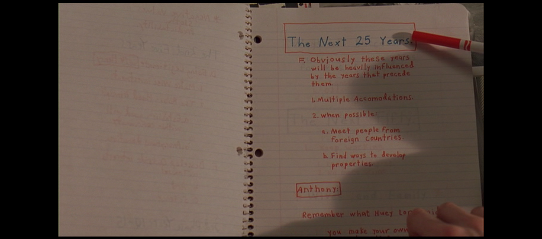

This is clear as well from contrasting the ways these men express their feelings to others. In Anthony’s case, he picks up a crayon and doodles Inez — tellingly without eyes or a mouth but with pronounced mammaries — riding a horse. The horse has nothing to do with Inez, or with any of her interests, or with anything he could possibly know about her. In fact, the only word he scrawls alongside the picture, three times, is her name…again, one of the very, very few things he knows about her, which should really remind the audience how shallow this “love” must be, in spite of everything the film wants to tell us to the contrary.

In Jack’s case, he expresses himself through the clearly more mature method of writing fiction. (I’m not trying to put my own literary tendencies on a pedestal here…I just think it’s safe to say that writing fiction is more or less universally understood to suggest more maturity than drawing on the backs of placemats with crayons.)

We don’t know that he will write about Rita, but we do know that he wrote about his experiences at the Hotel Chevalier and at Luftwaffe Automotive…two other scenes in the film that Jack could only process by writing about them. In fact, Jack may well not write about Rita. Why would he? She is one of many woman he will sleep with, and it’s possible that he won’t even remember her name.

Jack has a method of dealing with things — or, perhaps, a method of avoiding having to deal with them — and it’s up to him whether or not Rita should ever factor into that. She might not…she means nothing to him, and he always knew that. So did the film.

Anthony labors under the misapprehension that Inez means more to him than she really could, and so he picks up a crayon and gets to work. We do see Anthony doodle once more in the film — a nice flipbook animation of Dignan pole-vaulting during their upcoming heist — but it’s more a way of passing the time than it is any serious and mature exploration of the feelings and concerns racing around inside of him. Point: Whitman.

For Anthony, he and Inez get to live happily ever after, at least as far as the film is concerned. We leave Dignan in prison, Bob Mapplethorpe is getting along with his brother, and Anthony is happy with Inez, who plans to send Dignan a care package. Everything’s worked out just fine for these two crazy kids who couldn’t understand a word each other said and had nothing in common or any reason to connect or to continue corresponding, let alone develop their relationship into anything larger than “housekeeper” and “that creepy guy who fucked the housekeeper.”

It feels unearned, not least because Inez doesn’t even get to show up in person at the end of the film and let us know — in some way — what she’s feeling. We see that it makes Anthony happy, and that’s enough. Or is supposed to be. In reality, it just feels disjointed. Inez recoiled from him, then slept with him, then said she loved him, and then apparently entered into a serious relationship with him, but we never get any insight into why, or into how she might be feeling. Does Rocky still come along on their dates to translate? Bottle Rocket frames the situation as a triumph of romance, but it just feels like a story we can’t understand…perhaps as though it’s being told in an unfamiliar language.

For Jack there is no aftermath, because he was always aware that there wasn’t a relationship in the first place. There was no love involved. They had sex. Jack would have liked to have had more. When the Whitmans are kicked off the train Rita leans out of a window to offer him savory snacks, and something very strange and unexpected happens: she cries.

Unlike in Bottle Rocket, where emotion was constantly abound whether or not it was needed, appropriate or earned, here emotion was never part of the arrangement. Rita cries for Jack, because she feels sorry for him. Jack, hoping it’s not as personal as it really is, assumes she must have accidentally gotten maced during the brotherly spat that got them ejected.

He remains distant, and cold. He’s more comfortable without the personality, without the investment, and without the emotion. He walks to keep pace with the train as it pulls away, as the strains of “Charu’s Theme” play behind him. There was no music during the sex and no real soundtrack to the seduction, but here, at last, is Jack’s artistic overture toward romance: the goodbye. For Jack, the romance is in the heartbreak. He may not feel compelled to make every sexual encounter one to remember, but he sure knows how to make an exit.

Wes Anderson, as noted above, would do much better with handling cross-barrier romances in the future, whether it’s teacher / student, adopted siblings, or the stunted courtship of Ned Plimpton and Jane Winslett-Richardson. He made one mistake early on, but after those awkward romantic fumblings, he sure grew up fast.

Reader / humorist / friend (titles in ascending order of importance) David Black wrote in recently and asked a very interesting question. He was wondering if the obtrusive hallmarks of a Wes Anderson film could also be serving as barriers, holding his films back from being great in their own right. In other words, does Anderson’s strict adherence to being Anderson restrict the growth of his films?

My first instinct, of course, is to respond with a simple no, hit David very hard with the Royal Tenenbaums script book, and never speak of it again. But he’s far away and I actually do think it’s a topic worthy of consideration. After all, Anderson’s films — like Anderson’s characters — do erect walls between themselves and others. It’s part of what defines their identities. Dignan plots every step of his life 75 years in advance, Steve Zissou surrounds himself with script writers, camera men and original score composers so that he’ll never have to cope with an unstructured moment, and Francis Whitman distributes daily itineraries — laminated, natch — to keep his brothers ever on task.

Those are his characters, of course, but in a larger sense Anderson does the same thing. His scenes are dense and detailed, his dialogue deliberate and cautiously delivered, and his soundtracks meticulous. There’s rarely a moment in any of his films that feels spontaneous; it would work against what he does, and it would be well outside of his comfort zone. The films of Wes Anderson are almost painfully composed. You may not feel that his scenes are particularly lively or energetic, but allow your eyes to drift a bit to the margins and you’re going to find evidence of truly passionate, boundless and insatiable creativity…a carefulness of purpose that seeps much deeper into every scene than the words his characters are asked to speak.

Those are his characters, of course, but in a larger sense Anderson does the same thing. His scenes are dense and detailed, his dialogue deliberate and cautiously delivered, and his soundtracks meticulous. There’s rarely a moment in any of his films that feels spontaneous; it would work against what he does, and it would be well outside of his comfort zone. The films of Wes Anderson are almost painfully composed. You may not feel that his scenes are particularly lively or energetic, but allow your eyes to drift a bit to the margins and you’re going to find evidence of truly passionate, boundless and insatiable creativity…a carefulness of purpose that seeps much deeper into every scene than the words his characters are asked to speak.

Which, I think, becomes quickly the crux of my response. The hallmarks to which Dave alludes are clear, and his question about their accidentally subverting Anderson’s emotional thrust is valid. After all, what are some of the most common criticisms about Anderson’s films? Read a negative review or ask somebody who’s not particularly a fan, and you’re bound to hear things like “unnatural dialogue,” “unrealistic characters,” “coldness.” Perhaps Anderson is missing the forest for the trees, so to speak, spending so much time and investing so much of his energy in refining the details that he forgets to — or neglects to, or is unable to — provide an engaging and resonating emotional experience.

The question, as I say, is valid. The answer, however, relies on another question: is Anderson’s trademark detachment and ennui structurally consistent — or tonally sound — with whatever grander point he’s trying to make? Kurt Vonneget’s fourth rule of fiction writing is this: Every sentence must do one of two things–reveal character or advance the action. He was speaking about literature, but we can apply that to film as well, so long as we broaden our concept of the word “sentence.” And even though Vonnegut himself actively encouraged breaking these rules, it provides us with a decent baseline of intent: do each of Anderson’s details either reveal character or advance the action?

The question, as I say, is valid. The answer, however, relies on another question: is Anderson’s trademark detachment and ennui structurally consistent — or tonally sound — with whatever grander point he’s trying to make? Kurt Vonneget’s fourth rule of fiction writing is this: Every sentence must do one of two things–reveal character or advance the action. He was speaking about literature, but we can apply that to film as well, so long as we broaden our concept of the word “sentence.” And even though Vonnegut himself actively encouraged breaking these rules, it provides us with a decent baseline of intent: do each of Anderson’s details either reveal character or advance the action?

I would absolutely say yes, though Anderson’s intentions lean far more toward revealing character than advancing action. After all, in each of his films the seeming narrative thrust is subverted and replaced before it really gets moving, whether it’s Max getting expelled from The Rushmore Academy, Royal’s lie being exposed or the brothers Whitman being left behind by the titular train, Anderson is telling us in each case that the story is changing, all around us. We once meant to do this, but now, instead, we are going to do that. What happens isn’t important merely because it happened…it’s important because of how it made us feel. As the great Frank Zappa said, you should be digging it while it’s happening, because it just might be a one-shot deal.

Advancing the action is of comparatively little interest to Anderson, and he’s perfectly willing to bring it to a complete stand-still if it means we’ll get to spend more time learning about his characters…something that happens quite literally in The Darjeeling Limited when the train comes to a complete stop, leaving the Whitmans (and us) with an unplanned opportunity for ceremony and soul searching.

Advancing the action is of comparatively little interest to Anderson, and he’s perfectly willing to bring it to a complete stand-still if it means we’ll get to spend more time learning about his characters…something that happens quite literally in The Darjeeling Limited when the train comes to a complete stop, leaving the Whitmans (and us) with an unplanned opportunity for ceremony and soul searching.

But what do Anderson’s obtrusive hallmarks — the reason Dave asked this question in the first place — have to do with this? Well, on the surface, perhaps not much. Anderson’s characters are as deliberately constructed and detailed as his sets, something even his detractors would admit, but these details can serve as deterrents to digging deeper, and finding a real human being inside. That’s something that some would call a weakness, but it’s exactly what Anderson wants. He may well overtly manufacture his characters, but since these characters overtly manufacture their lives, that’s a pretty fitting approach, thematically speaking. In fact, I think it’s much more helpful to view the question from the ground up: instead of looking at Anderson as a man creating these characters, look at the characters themselves, and then see Anderson’s methods as a way of telling their stories while remaining true to who they are.

It’s difficult — and intimidating — to dig into Anderson’s characters in order to find a shred of humanity, but that’s not Anderson’s shortcoming; it is true the personas his characters deliberately cultivate. The most obvious example of this is Richie Tenenbaum, who isolates himself at sea, and behind sunglasses, and behind a curtain of hair, to prevent anybody from seeing who he really is. After his public meltdown he very much retreated from the world, and erected barricades to keep himself safe — if not exactly sane. When he finally lets down those walls, even in a solitary, dark bathroom, he sees the damaged and weak human being within, and he attempts to destroy it.

It’s difficult — and intimidating — to dig into Anderson’s characters in order to find a shred of humanity, but that’s not Anderson’s shortcoming; it is true the personas his characters deliberately cultivate. The most obvious example of this is Richie Tenenbaum, who isolates himself at sea, and behind sunglasses, and behind a curtain of hair, to prevent anybody from seeing who he really is. After his public meltdown he very much retreated from the world, and erected barricades to keep himself safe — if not exactly sane. When he finally lets down those walls, even in a solitary, dark bathroom, he sees the damaged and weak human being within, and he attempts to destroy it.

Richie’s attempted suicide is a self-fulfilling prophecy. He was afraid that if he let anybody inside, they would hurt him. Therefore the moment he lets himself inside, he knows what must be done.

In a less drastic sense, we can see deliberately cultivated quirk serving as emotional barricades for his siblings as well, which serves to underscore the fact that Anderson chooses these details carefully, rather than slopping them on for the sake of confounding audiences. In the case of Chas Tenenbaum, the matching red track suits that he wears with his two boys are a way of both pressing his sorrow inward — his wife’s death, which must be re-internalized every time he slips into the outfit — and sheltering himself and his family from ever facing it again, with the bright red uniforms becoming, suddenly, identifiable beacons in the event of tragedy.

It’s an unspoken detail strengthened by the fact that the closest thing to a real tragedy — a car accident that kills his dog and nearly his sons — occurs once the track suits are removed. Its removal also, however, allows Chas to soak in the full benefit of a Zen garden, and without his protective shell he’s much more receptive to his father’s unexpectedly selfless gesture: buying the family a new dog. Being freed of this physical trapping allows Chas to admit to the true depths of his sorrow, something he was never able to do earlier, opting instead to storm off and internalize.

It’s an unspoken detail strengthened by the fact that the closest thing to a real tragedy — a car accident that kills his dog and nearly his sons — occurs once the track suits are removed. Its removal also, however, allows Chas to soak in the full benefit of a Zen garden, and without his protective shell he’s much more receptive to his father’s unexpectedly selfless gesture: buying the family a new dog. Being freed of this physical trapping allows Chas to admit to the true depths of his sorrow, something he was never able to do earlier, opting instead to storm off and internalize.

A similar — though differently functional — affectation can be seen in the case of Margot Tenenbaum, who — for reasons equally unspoken — chooses to wear a wooden replacement for her missing finger, both visually and aurally obtrusive, rather than something a bit less conspicuous. To many, this might seem like just one more of Wes Anderson’s distracting details that allow him to focus on design over character development, but for Margot it’s a symbol of her own detachment. She wears it like a scar, and draws attention to it so it won’t be forgotten.

Throughout the film she stands apart from the rest of her family, likely a result of Royal’s tendency to inform people up front that she’s adopted, and therefore not technically his. This unwitting familial detachment became a defining feature of her personality, and ultimately manifested itself physically during a visit to her biological family, where her finger is accidentally severed, and her outfit and demeanor make clear that she’s necessarily detached from that family as well. Her missing finger is a symptom, and a reminder of a completeness she will never feel.

Throughout the film she stands apart from the rest of her family, likely a result of Royal’s tendency to inform people up front that she’s adopted, and therefore not technically his. This unwitting familial detachment became a defining feature of her personality, and ultimately manifested itself physically during a visit to her biological family, where her finger is accidentally severed, and her outfit and demeanor make clear that she’s necessarily detached from that family as well. Her missing finger is a symptom, and a reminder of a completeness she will never feel.

I think that instead of Anderson’s hallmarks standing as obstructions to genuine greatness, they instead help inform a cohesive whole. His films work better with a cumulative impact, meaning more and reaching deeper the more of them you experience. One film on its own may or may not move you, but viewing several will give you a better opportunity to feel moved by his uncommon methods. And like the unreliable narrators of Nabokov or the deliberately terrifying specificity of Pynchon, these are similar devices deployed differently each time, seeming similar when viewed from a distance but, once studied, revealing themselves to be impressive variations upon what we may have thought was a barren theme.

Consider, for instance, Max Fischer in Rushmore. Max also lives an affected life, with a deliberate bearing and an impressive attention to detail. But this is a life he has manufactured in order to detract from what’s actually there: he is a barber’s son. He piles on extracurricular activities to distract from his less impressive curricular performance. He creates art, wills companionship and outright lies about his father’s vocation and sexual exploits, all in the service reinforcing a bubble around himself, constructing a world that means everything to him that he wished the world could mean on its own. He even demands control over his soundtrack, bringing a cued-up cassette tape along when he makes his move on Miss Cross, and signaling to a disc-jockey to play Ooh La La as an indication of the progress he’s made…even as such a gesture tends to call that very progress into question.

Consider, for instance, Max Fischer in Rushmore. Max also lives an affected life, with a deliberate bearing and an impressive attention to detail. But this is a life he has manufactured in order to detract from what’s actually there: he is a barber’s son. He piles on extracurricular activities to distract from his less impressive curricular performance. He creates art, wills companionship and outright lies about his father’s vocation and sexual exploits, all in the service reinforcing a bubble around himself, constructing a world that means everything to him that he wished the world could mean on its own. He even demands control over his soundtrack, bringing a cued-up cassette tape along when he makes his move on Miss Cross, and signaling to a disc-jockey to play Ooh La La as an indication of the progress he’s made…even as such a gesture tends to call that very progress into question.

(As an amusing sidenote, Jason Schwartzman’s character in The Darjeeling Limited shares this compulsive control over his life’s soundtrack, relying on his iPod in the same way that his brother relies on his laminating machine to keep the universe in order.)

All of which leads me to believe even more strongly that Anderson’s hallmarks are not just hallmarks, but appropriate showcases for his characters, and respectful echoes of who they wish to be. Rushmore itself is structured like a play, with act breaks and a curtain call, a framing device that draws even greater attention to Max’s careful manipulation of the world around him. He constructs literal scenes on stage, but sees the world around him with a similar directorial eye. Anderson’s shots and soundtrack may have been carefully chosen, but it’s pretty fair to say that he is being true to Max, who would have chosen the same ones. Had Bert Fischer been the central character, we would instead have seen a diminished level of attention, a softer and more optimistic viewpoint, and — if the music in his barber shop is any indication — a soundtrack of cool and unobtrusive jazz.

All of which leads me to believe even more strongly that Anderson’s hallmarks are not just hallmarks, but appropriate showcases for his characters, and respectful echoes of who they wish to be. Rushmore itself is structured like a play, with act breaks and a curtain call, a framing device that draws even greater attention to Max’s careful manipulation of the world around him. He constructs literal scenes on stage, but sees the world around him with a similar directorial eye. Anderson’s shots and soundtrack may have been carefully chosen, but it’s pretty fair to say that he is being true to Max, who would have chosen the same ones. Had Bert Fischer been the central character, we would instead have seen a diminished level of attention, a softer and more optimistic viewpoint, and — if the music in his barber shop is any indication — a soundtrack of cool and unobtrusive jazz.

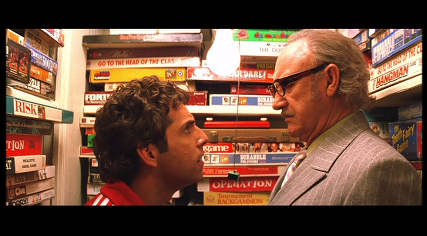

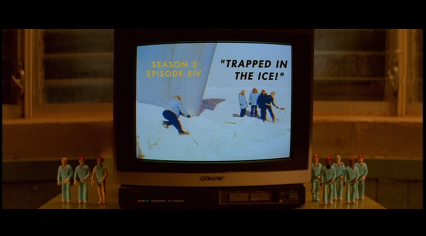

It’s clear, I think, that Anderson’s characters need this sort of careful composition if they can ever feel at home, and he chooses locations that are conducive to such isolated structuring, whether it’s The Rushmore Academy, 111 Archer Ave. or the Belafonte research vessel. These are the worlds Anderson has created, yes, but they’re also the worlds his characters have created, plying their own layers of history and detail into every room and onto every shelf, whether it’s a massive collection of board games in the closet or a set of out-of-production action figures flanking the television, some method of keeping reality at bay…some protection against a harsh world that has already moved on, and continues to move on, without you.

It’s clear, I think, that Anderson’s characters need this sort of careful composition if they can ever feel at home, and he chooses locations that are conducive to such isolated structuring, whether it’s The Rushmore Academy, 111 Archer Ave. or the Belafonte research vessel. These are the worlds Anderson has created, yes, but they’re also the worlds his characters have created, plying their own layers of history and detail into every room and onto every shelf, whether it’s a massive collection of board games in the closet or a set of out-of-production action figures flanking the television, some method of keeping reality at bay…some protection against a harsh world that has already moved on, and continues to move on, without you.

I don’t think Anderson’s hallmarks serve as barricades, and they won’t as long as he continues to find new ways to apply them, and interesting directions with which he might explore his themes. I think they instead spotlight the self-inflicted trappings of his main characters, and the walls within which they remain their own prisoners. Anderson simply revels in exploring the smallness of the worlds around his characters, and mapping the boundaries that hem them in.

As an artist, he’s revealing character…albeit in an off-putting, defensive, oblique way. And what better way to be true to characters that work so hard to do the same?

[Note: This article originally appeared in an earlier version on Noise to Signal.]

With the looming release of Moonrise Kingdom, it’s a given that we’ll soon find ourselves awash in reviews that, predictably, betray their authors’ confusion at what it is Wes Anderson — in a word — does.

Not so much what Wes Anderson does with a particular film itself, but what Wes Anderson does as a film maker working today. Reviews often seem to want to discuss all of his films at once, and make grand dismissive statements about wooden characterization, a complete lack of emotion, and the impossibility of any human being relating to the feelings or motivations of his characters.

In response I issue this…a list of what I feel are ten thoroughly, genuinely, painfully affecting moments in his films. Anderson might not handle emotion the way most American filmmakers handle emotion (read: tears, strings and rain), but the films of Wes Anderson provide a clued-in audience with some of the most sincerely (and strangely) moving moments, which haunt and linger far longer than those of his contemporaries. So read on, share, and enjoy.

Oh, and before anyone asks…no. I did not forget about Bottle Rocket or Fantastic Mr. Fox.

The Royal Tenenbaums is segmented into chapters, like a novel, or possibly a biography. But one scene stands outside of the film’s literary organization: between Chapter Three and Chapter Four, we have a lengthy installment entitled Maddox Hill Cemetery. It’s here that various characters pair off — and re-pair off — for the sake, yes, of plot development, but also for some of the film’s most truly painful Tenenbaum interaction.

From Royal shaking a few flowers free of his own bouquet for the grave of Chas’ wife to Richie giving his signature silent greeting to a passerby who recognizes him from his glory days, Neither Anderson nor his actors nor his original score composer, stumble at all. Everything is here, either spoken or unspoken. We see exactly why the Tenenbaums, on some level, yearn to operate together as a family, and also — more apparently — why they never can.

It’s appropriate that Maddox Hill Cemetery stands without a chapter number…it exists, moreso than any other sequence in the film, during several time periods, with each of the Tenenbaum children having a flashback that explains at least partly the gap between their glorious childhood and their tormented adult lives.

Composer Mark Mothersbaugh understands this scene on some level far beyond the structural and even the emotional. He understands what fuels the world in which The Royal Tenenbaums exists, and his score for this scene ranks high among his absolutely strongest work. His score here is beautiful, bashful, and aware of its own limitations. This is the music you would hear if you dropped a phonograph needle onto Richie Tenenbaum’s heart, and it stirs that rare, perfect emotion that can only be felt when a brilliant director, a brilliant cast and a brilliant composer work off of each other in profound harmony.

One of Max Fischer’s crimes against himself — perhaps his cardinal offense — is his habit of fixing his gaze on objects beyond his reach, and missing out on everything that’s right by his side, just waiting for him to come back around.

He seems to come to this realization himself toward the end of Rushmore, when classmate Margaret Yang stumbles upon him flying a kite. Margaret forces him to face the fact that his self-important social climb has emotional consequences as well. “You’re a real jerk to me,” she says. “You know that?” And we know that her words have taken root, because he actually apologizes — a defining moment for a very-much-changed Max.

He is sorry, because by this point in the film it’s clear his pursuit of Miss Cross has come to nothing…and a young woman who’s given him sympathy and support has been actively hurt by his callous inattention.

There’s more than a little caution — however unintentional — present in the little story she tells him as well: her science fair project was a lie. She faked the results. Max understands the gravity of what she has said here, and it stings. In fact, it’s why, immediately afterward, he decides to atone for his own falsified data by introducing Mr. Blume to his father…the barber.

One very interesting thing about The Darjeeling Limited is that its two most affecting scenes are intertwined with one another (structurally, this one is sandwiched between two halves of the other), so that all of the film’s most brutal emotion comes in one continuous hit. Typically Anderson spreads it thin, leaving lines and gestures stranded in places sometimes very far removed from the previous or next display of emotion…not so here.

But that’s not to say he does it any less adequately in Darjeeling. In fact, this particular scene, in which the three Whitman brothers attempt without success to drive their father’s car to his funeral, is among Anderson’s finest achievements, hands down. (In fact, I’d venture to say that it would work better as a short film than Hotel Chevalier did.)

The entire scene is a display of thoroughly misplaced attention, as it’s more important to the Whitmans to drive to their father’s funeral in a symbolic vehicle than it is for them to make it on time, and they end up, it’s suggested, missing the event entirely for all their fussing. It’s symptomatic of the problems they must have faced as a family all along: it’s not that they can’t work together, it’s that when they do work together, they’re pulling in the wrong direction.

But it’s still touching, and more than a little painful, when they try their best to do what they feel must be done, and this manic several minutes, deliberately plucked from a very different place and time in their lives, is highlighted by the most impressive display of brotherhood we ever see from the Whitmans when they threaten and stare down a tow-truck driver who nearly crashes into them. Was the tow-truck driver in the wrong? Of course he wasn’t. But even when the Whitmans manage to pull together, they’re pulling in the wrong direction.

Dr. Guggenheim’s stroke brings Max Fischer and Herman Blume together again for a brief ride in an elevator that somehow, without really saying anything, says absolutely everything anyone needs to know about these characters.

There’s not so much an obvious awkwardness between the two as there is an unspoken yearning to reconnect. They miss each other. Serious topics are touched upon (Blume’s divorce, Miss Cross’ whereabouts) but neither man is able to say anything much of substance. They bat a few banalities back, and forth and ultimately refuse eye contact.

But there is a love there…that love that rides a mutual respect, and can never quite be killed. Blume’s initial “Hey, amigo,” is a clear linguistic nod to the fact that he would still love to consider Max a friend, but cannot actually bring himself to use the word. And Max’s final line upon Blume’s departure (“Hey, is everything okay?”) is helplessly genuine. Blume’s confession of loneliness is made all the more painful by the logistical fact that, as he says it, he only allows Max a few of the back of his head. As much as they need each other, and even as they reach, they can’t yet let each other in.

When I first put together this list, five long years ago, this was one moment that I considered, and ultimately put aside. Today, I can’t account for that decision, as it’s sincerely one of the most touching things in a movie bursting with emotional merit.

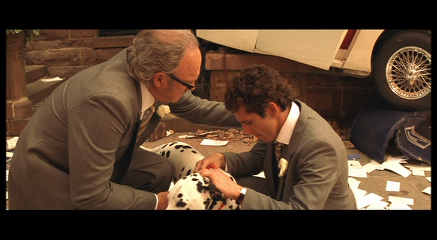

As Royal Tenenbaum attempts to reconnect with his family, he meets with varying degrees of success from each of them. Without any question, however, the most difficult obstacle he has to face is Chas. Chas has been both robbed and shot by his father during the course of his childhood, but what stings most for him is the fact that his dad let the family fail. When his parents separated the children were never the same, and Chas’ channeled his frustration at his parents into shaping his own family unit, providing for them a secure and stable environment that was ultimately ripped away from him by the plane crash that took his wife.

Chas did indeed have a rough year, but that’s not what makes the moment so important. It’s not the confession, but who he’s confessing it to. As much as Chas kept his emotions to himself, it’s ultimately the father who hurt hum so much that gives him the comfort he needs. The tears he cries when Royal buys his boys a new dog to replace the recently departed Buckley are real, and he sees a sincere selflessness in the gesture…one that’s superficially small, but relatively enormous.

Chas lets his father back in, but Royal is not long for this world, and he himself dies not much later. In a twist neither man could have seen coming, Chas is the one who spends Royal’s dying moments with him. It’s a profoundly emotional coda to the most openly antagonistic relationship in a film rife with them, and it’s all elevated by the genuinely moving portrayal of Chas by Ben Stiller. Proof positive that Wes Anderson can work wonders with just about anyone, and a moment as deserving of a spot on this list as any other.

We know very little of Ned’s life before he joined up with Team Zissou, and, as far as the interests of the film are concerned, that’s a good thing. It makes his last moments on board the Belafonte that much more significant.

Had we been granted a more comprehensive view of his life, Team Zissou would represent only a small portion of all those he came to know. With our much narrower perspective, the ship’s crew represents everybody we’ve seen him interact with, and their turnout to wave farewell before his final flight is almost overpowering in its significance. None of these characters suspects that they will never see him alive again, and yet they’re all there…seeing him off. It’s just one of those many morbid coincidences that none of these characters would really understand.

Most touching is Klaus’ farewell, which includes, importantly, an olive-branch by way of salute. He wants Ned to know how much it means to him that he worked a K — for Klaus — onto the redesigned Team Zissou insignia, but more importantly he wants him to know that he’s at last ready to accept him as a fellow member of the crew. (And, in terms of the de-facto Zissou family, a brother.)

Steve is the only one who does not get the chance to say goodbye to Ned, though he is present for his final moments, and it is he who pulls his body to shore. It’s more than a little telling, as well, that the sharp cuts in Steve’s “death vision” sequence are so similar in style to those of Richie Tenenbaum. The difference, of course, is that Richie lived a full emotional life with much to reflect upon…while Steve’s visions are nothing more than flat colors, bubbles rushing to the surface, and one fleeting, final glimpse of Ned, who financed the voyage monetarily, and then, with more than a little symbolism, paid for it with his life. Steve falling to his knees on shore with the body of the man who was — for all intents and purposes — his son is a beautifully framed, hauntingly understated moment of silent, unforgettable sorrow. But Ned’s not the only one to come to an early, watery end…

The turning-point for Peter Whitman (and arguably for the film itself) comes when the three brothers see three young Indian boys fall helplessly into a dangerous river. That’s one boy for each brother, right? And because they’re well-to-do Americans they get to play automatic heroes. There’s nothing at all at stake when the Whitmans dive in after the boys. Mathematically, everything is going to be just fine.

Imagine, then, the shock to Peter Whitman when he fails to save one of the children. He emerges from the river bloodied and bruised, carrying a lifeless body, and he’s so far beyond emotion that he can’t do anything but mutter flat, impotent confessions. “I didn’t save mine.” “He’s dead.” “The rocks killed him.” The audience might believe, initially, that Peter’s blow to the head left him stammering, but it’s clear before long that the real damage was wrought more deeply. His entire sense of life and possibility has been thrown for a loop–he was not the hero he expected himself to be. In fact, he was a failure. He ends up carrying a dead child to a grieving father, in a land he does not know or understand, and though Peter does not cry, it’s not because he feels nothing; it’s because he feels a sorrow too large to convey.

The Whitman brothers spend a good deal of time in this village, and Peter may never be able to atone for what’s happened, but he does come out of the experience with a much matured view of his own impending fatherhood, which now holds an unexpected meaning for him. He may not be a completely changed man but, after this incident, he is no longer the man he was just a few days earlier, when he openly considered leaving his wife before his child was born.

Adrien Brody, as of this film, is a newcomer to Anderson’s menagerie of reliable actors, and as of this precise moment, when he emerges from the river stuttering helplessly about the child whose life he could not save, he establishes himself as a perfect fit. (Also, for the record, Brody wins the Saddest Eyes award for The Darjeeling Limited, which is always a serious achievement in a Wes Anderson film.)

There’s no greater change wrought in Max throughout the course of Rushmore than the one so clearly on display when he humbly introduces Mr. Blume to his father. He is letting Blume see a side of him that very few people have been invited to see, but also he is showing it to himself, letting himself, for once, be reflected in his own eyes.

One great thing about this scene that can easily go unnoticed is that the two adults are each aware of more than they’re actually saying. Mr. Blume had earlier been led to believe that Max’s father was a neurosurgeon, and it’s safe to assume that Mr. Fischer is aware that his meager occupation has probably been kept a careful secret by his enterprising son…and yet neither of them speak of it. Blume’s heart breaks, and you can see it in Bill Murray’s supremely expressive eyes, not just because he’s been allowed a glimpse behind Max’s carefully constructed shell, but also because he feels acutely the distance between father and son, preventing both parties from connecting the way they’d each like to — and need to — connect.

“I don’t know, Burt,” says Blume, apropos of nothing, and it’s one of the most honest lines in the film. Something real is being revealed to him here, and he’s incapable of coping with it. Some silent lesson is being preached, and he’s aware that its moral will be at least somewhat lost to him. He envies the simplicity of the barber’s life, and at the same time understands precisely, guiltily, the reason Max aches to rise above it.

When Steve Zissou finally comes face to face with the Jaguar Shark, there’s very little he can do but ponder the wisdom of his journey, and reflect — wordlessly — upon everything his crew has had to endure in pursuit of his purely selfish, short-sighted revenge.

The submarine (aptly named Deep Search) contains what remains of his crew and his family…along with a business partner, a reporter, an intern, and a representative of the bond company, all of whom have suffered in some tangible way for the advancement of Steve’s goal. And yet, when he finally reaches that goal, he breaks down. He cries openly, for the first and only time in the film. He gains — a long, long way into his life and career — some perspective of the greater world around him, and he sees, at last, how little right he had to so carelessly jeopardize other people’s lives.

The real weight in the scene is the non-presence of Ned, who died in pursuit of the beast, and we suspect that the death of his previous crewmate Esteban sits heavy on Steve’s conscience as well. His emotion is coming from the fact that it took him too long to realize the price of his revenge, and that what’s lost is really lost forever. There’s no way to go back and undo the very real damage he’s done along the way.

He is forgiven, however, in the midst of his wordless reflection, by those along for the ride on Deep Search. One by one, his remaining companions each lay a comforting hand on him. There are no accusations, and there is no anger. They find themselves in a submarine with a captain who has at last become fragile and human, and, one hand at a time, they do their part to hold him together.

There’s very little that can be said of a scene that says everything itself so well. Relied upon — and used — by so many others as the most level-headed and caring of the Tenenbaum family, the viewer is more aware than any of the characters how much suffering he internalizes. And so, when at last he learns more about his adopted sister than he was ever prepared to know, and he walks slowly and quietly out the door without saying a word, we know that something is about to happen, and it’s not going to be good.

Elliott Smith’s terrifying “Needle in the Hay” starts up, and Anderson does something very clever by starting it over an unrelated scene, in which Royal converses hopefully with a hotel manager about a job. A first-time viewer would never catch it, but upon each subsequent viewing those dark, razor-sharp chords bring a very vivid image to mind, and throughout a comic scene we are inescapably aware of a parallel tragedy.

The entire sequence with Richie in the bathroom is cut brutally, hastily…it doesn’t flow; it’s been hacked to pieces. This serves to echo not only the immediate content of the scene, but also the end to which it builds. His cutting away at hair, his beard, and then, desparately, his wrists.

It’s Anderson at his most fearless; he’s triggering emotions, but not allowing anyone to get caught up in them. There is no moment during which any characters take pause to weep. The score is not touching — it’s tough and tightly-squared. It’s played blue and emotionless, which is, of course, why it works so well. We are not asked to align ourselves with anybody else’s emotions…we are supposed to view what is happening from the perspective of an outsider. We are meant to feel growing concern as Richie removes his headband, his hair, his beard, his glasses…as he exposes himself at last to the world he sought so strongly to shut out. Layer by layer he is shaving himself down, becoming more vulnerable. And when he sees what’s beneath — that young man who, at one point, could have had absolutely anything — he attempts to destroy it.

We are allowed brief dips into his thought process by means of abrupt, almost subliminal flashes of film we’ve already seen, and it’s not so much meant to represent a dying man’s last glance backward as it is meant to highlight the agony of a man who can no longer stand to be alive.

Richie Tenenbaum still stands as Anderson’s most tragic character, and certainly the least deserving of his own pain. And that’s precisely what makes him so real.