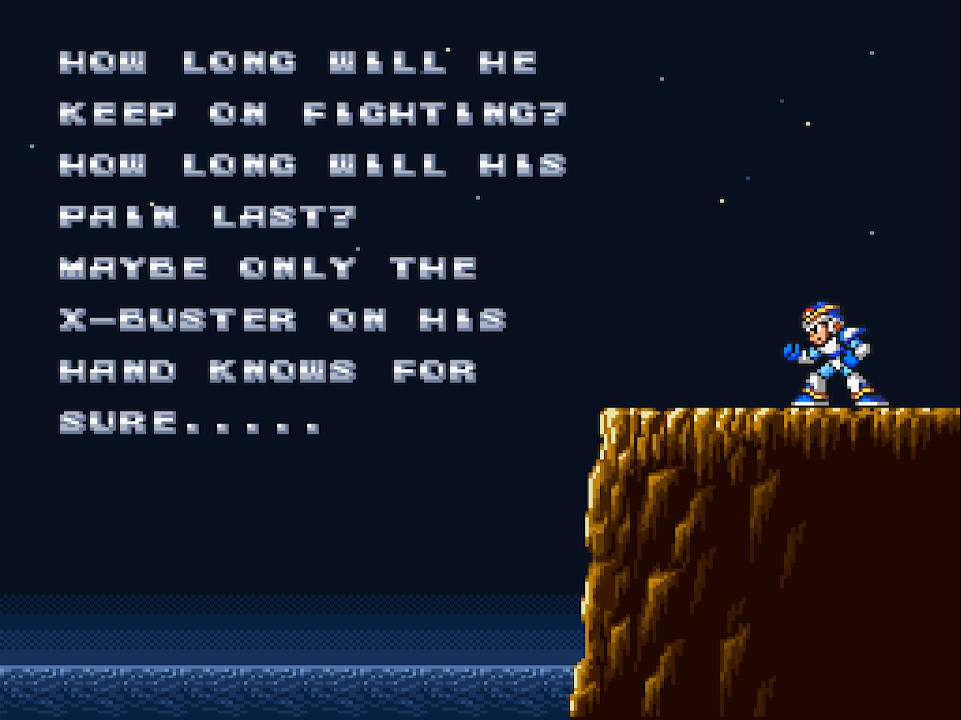

A quick note of clarification for anyone arriving from the future (which, I suppose, all of you are): I wrote my Mega Man retrospectives in sequence, and I’m now moving back in time to cover the Mega Man X games. You’re welcome to read them in whatever order you like, but this was written after my retrospective on Mega Man 11.

With that out of the way, let me say that the Mega Man X retrospectives are going to be quite different from the Mega Man ones, simply because I have a great deal of childhood memories associated with those games and I have next to none associated with these.

I grew up with those games. I remember them always being there as a comforting presence. They were too difficult for me to finish, but I always enjoyed getting as far as I could, scribbling down passwords, hoping that my 20th attempt to finish a stage the exact same way would, somehow, work this time. (I wasn’t much one for developing new strategies as a kid.)

Mega Man games were always among my favorites, but the Mega Man X games didn’t make much of an impression on me. In fact, I can share all of my childhood experience with them here, in a short section of this review alone.

I rented the first game, or perhaps a friend did. I do remember playing it, and I essentially just thought it was a Mega Man game on the SNES. My brain didn’t even attempt to process it beyond that. I was willing to believe that the X was a Roman numeral, signifying that this were the 10th Mega Man game, rather than that it was a spinoff or the start of a new series.

I’m sure I was baffled by the fact that the game dumped me into a level as soon as it started, rather than giving me a stage-selection screen. I’m sure I finished that intro stage and then tried each of the main levels at least once. I’m sure I struggled with the game and played it poorly. That’s about all I can say for sure. It was just another Mega Man game.

Of course, it wasn’t, but I thought it was. And I knew what Mega Man games were, so if Mega Man X didn’t grab me right off the bat, there was no reason to keep going. I knew the formula. I understood the concept. If I loved it, like I loved most of the others, great. If I didn’t, I’d never have to think about it again, and I’d miss nothing by moving along.

I was wrong. Much of what I’ll talk about here will focus on the fact that the game was recognizably Mega Man, but it differed in significant, exciting, and important ways. It was the rare spinoff that felt both true to its parent series and also worked as a unique deviation that was just as influential in itself. Young me, aged 13 or so, was a big dummy and dead wrong.

…but you can’t blame me totally for being dead wrong. As much as Mega Man X is a solid and well-crafted experience of its own, it also leaves the door puzzlingly open for confusion.

If you go into the game knowing that it’s the start of an entirely new series, as it’s easy to do today, that’s no problem. In 1993, though, if you were just looking for something to play and saw the name Mega Man, you were probably going to be misled.

The cynic in me is happy enough to conclude that this was deliberate. A game called, say, Robot Fighter X with a character who looked completely unique might have sold very well. It also might have sold very poorly. There’s no way of knowing. But a game called Mega Man X with a character who looked very familiar was guaranteed to shift a good number of copies on the strength of familiarity alone. That may have been a calculated decision to make the game just look like another sequel, but that decision sure did work against anyone at the time understanding what the game was.

Let’s break down the similarities up front.

The name of the game is Mega Man X. Okay, right, you know that already, but I’m making a point: The protagonist’s name is only X, but thanks to the game’s title and its English localization, we are basically calling the main character Mega Man.

The main character also physically resembles Mega Man; he’s a robot boy with similar boots, a similar helmet, and a blue color scheme. He looks different, sure, but everything looked different on a 16-bit system when you were used to 8-bit systems. This could have just been what Mega Man looked like now; we didn’t have a proper 16-bit Mega Man to compare this to. (The Wily Wars on the Genesis wouldn’t be released until the following year, and Mega Man 7 on the SNES wouldn’t be released until 1995.)

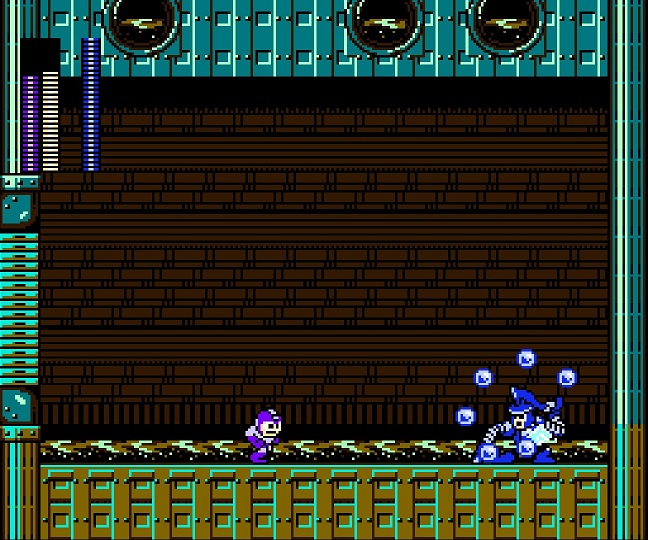

This character could be defined by the differences in his abilities, but, at the start of the game, you won’t notice any. His arm cannon fires what seem to be the same shots as Mega Man’s, at what seems to be the same rate. Hold down the button and you’ll charge up a shot, just like Mega Man. You can’t slide anymore, but that alone hardly suggests that this is a completely different character.

The more you play the game, the more differences will become apparent. You’ll be able to upgrade your health, defenses, and charge shot. You’ll learn how to dash. You’ll figure out how to wall jump. But at first, here, seeing the game for the first time, controlling your character for the first time, working out in your mind what this game is for the first time, it just feels like Mega Man.

And though it is true that you’ll discover more differences between X and Mega Man as you play, you’ll also discover more similarities, balancing the scales a bit.

For instance, you’ll eventually get to the level-select screen, allowing you to choose from eight themed bosses in whatever order you like. When you pick a stage, you’ll see the boss appear on screen and taunt you with a threatening pose, with an SNES version of the same tune you heard when picking a stage in Mega Man 2 and Mega Man 4. (And Mega Man, I suppose, but Mega Man X includes the later refinements to that composition.)

You fight through the stage, of course, maybe having to battle a miniboss, then eventually defeat the pattern-heavy main boss at the end, who has his own dedicated health bar presented, like yours, in a decidedly Mega Man-like fashion. When you defeat him (because they’re all him, even if they’re no longer called Man), you get a version of his weapon to use for yourself. Equip the weapon and you change colors. That weapon is the weakness of one other boss, which will make defeating that boss easier.

So far, so similar, and it doesn’t stop there. Clear all eight main stages, and you’ll gain access to the fortress, a series of even more difficult stages that test your mastery, confront you with bigger, meaner bosses, and require you to fight the eight main bosses all over again. (This time, in a nod to the first Mega Man, you don’t choose the order; you refight them in a predetermined sequence as you progress.) Make it to the very end and you’ll fight the final boss in two distinct phases.

Are there more differences along the way? Absolutely. But when you lay it out like that, it’s hard to see how (or why) Mega Man X is part of a distinct series from Mega Man. It sounds far, far more like a sequel than it does a spinoff. If you only play it for a short period of time, that’s how it feels as well.

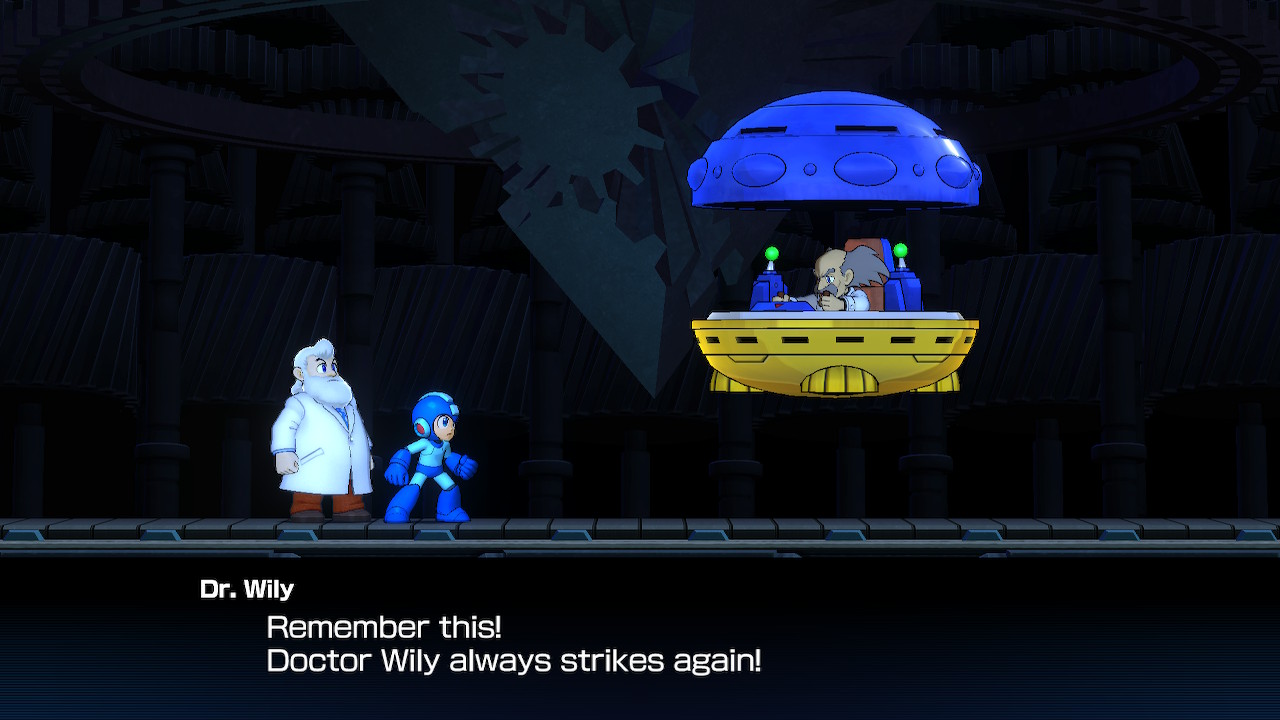

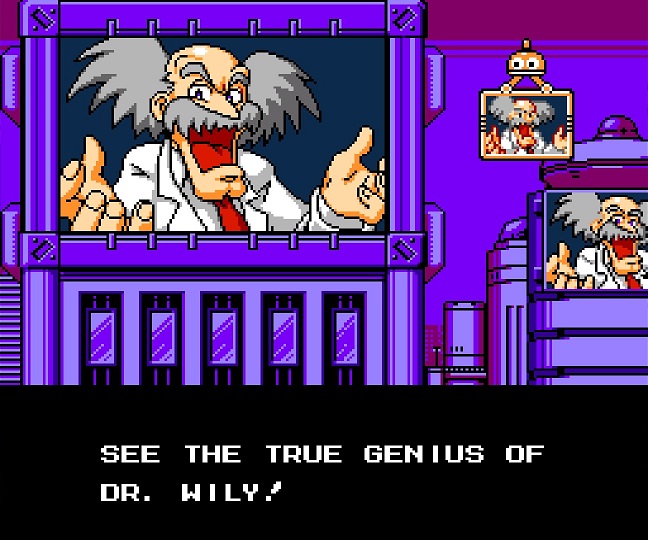

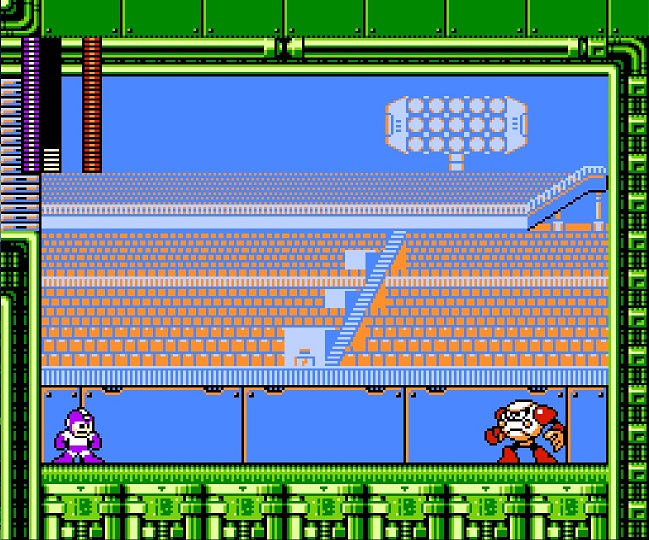

X looks and plays like Mega Man. Zero looks like and seems to serve a similar purpose to Proto Man. X’s handler Dr. Cain doesn’t make a physical appearance, but we assume that he’s the new Dr. Light. Big bad Sigma fills the same structural purpose as Dr. Wily. Instead of fighting Robot Masters, we are fighting Mavericks. As Jon Bon Jovi put it in his famous review of Mega Man X, “It’s all the same; only the names have changed.”

Like I said, though, it feels that way if you play it for a short period of time. If you play it extensively, thoroughly, repeatedly, you understand what makes Mega Man X stand out: For the first time in the entire series, the protagonist has a character arc that unfolds not just narratively but mechanically. Let’s take a look at how that works.

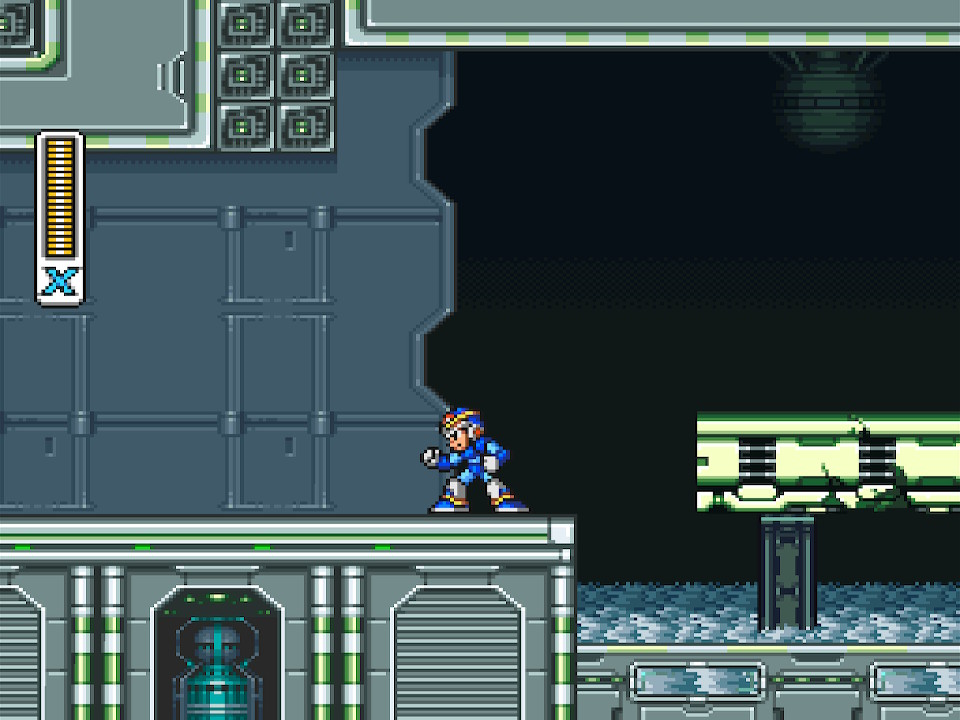

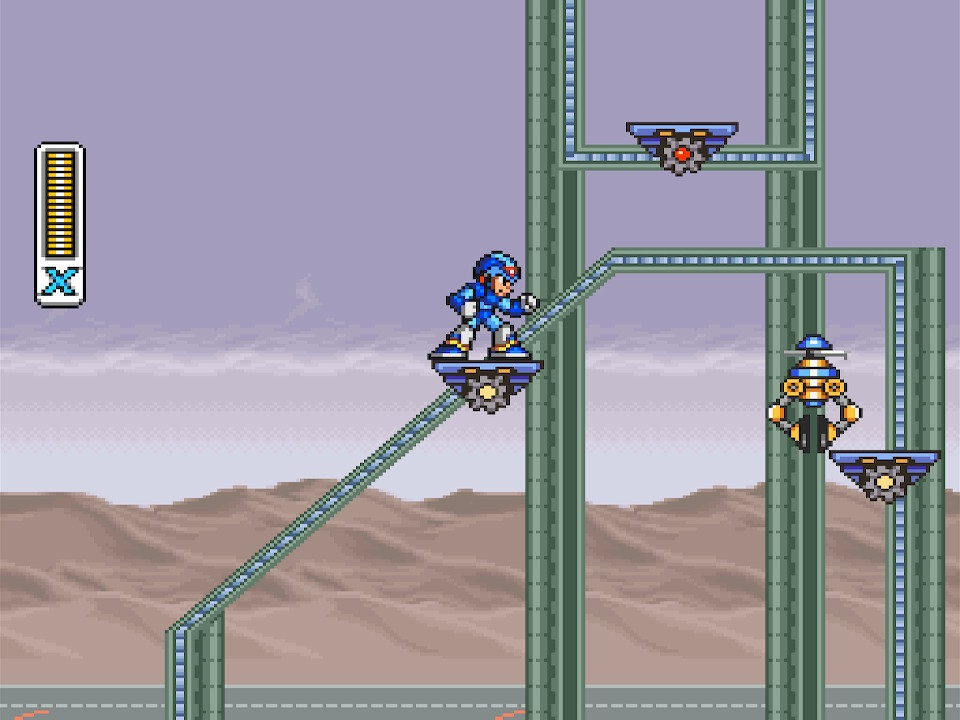

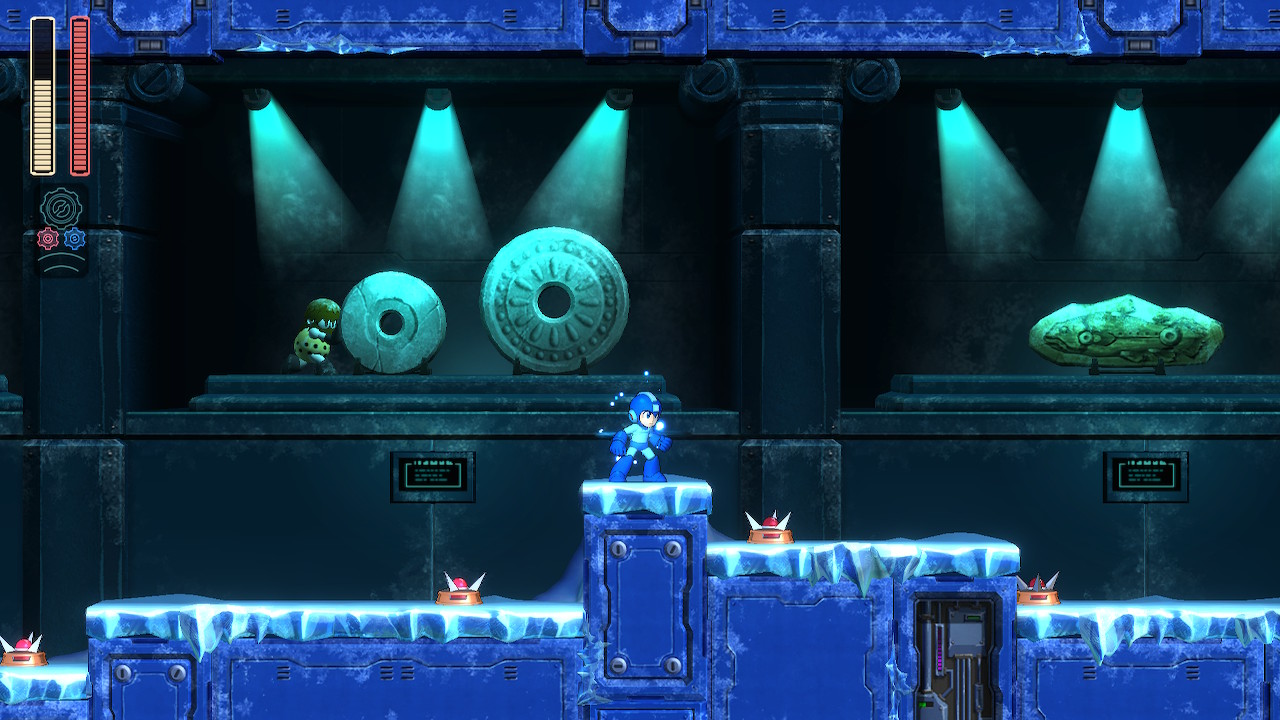

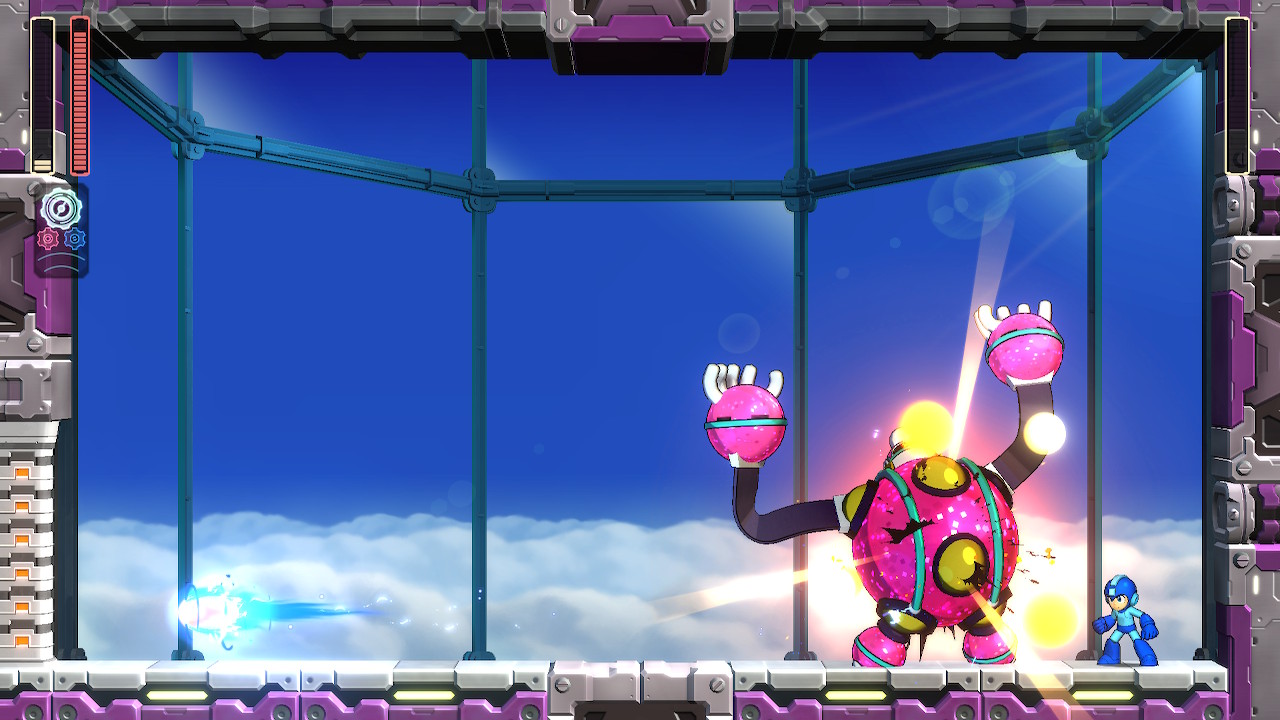

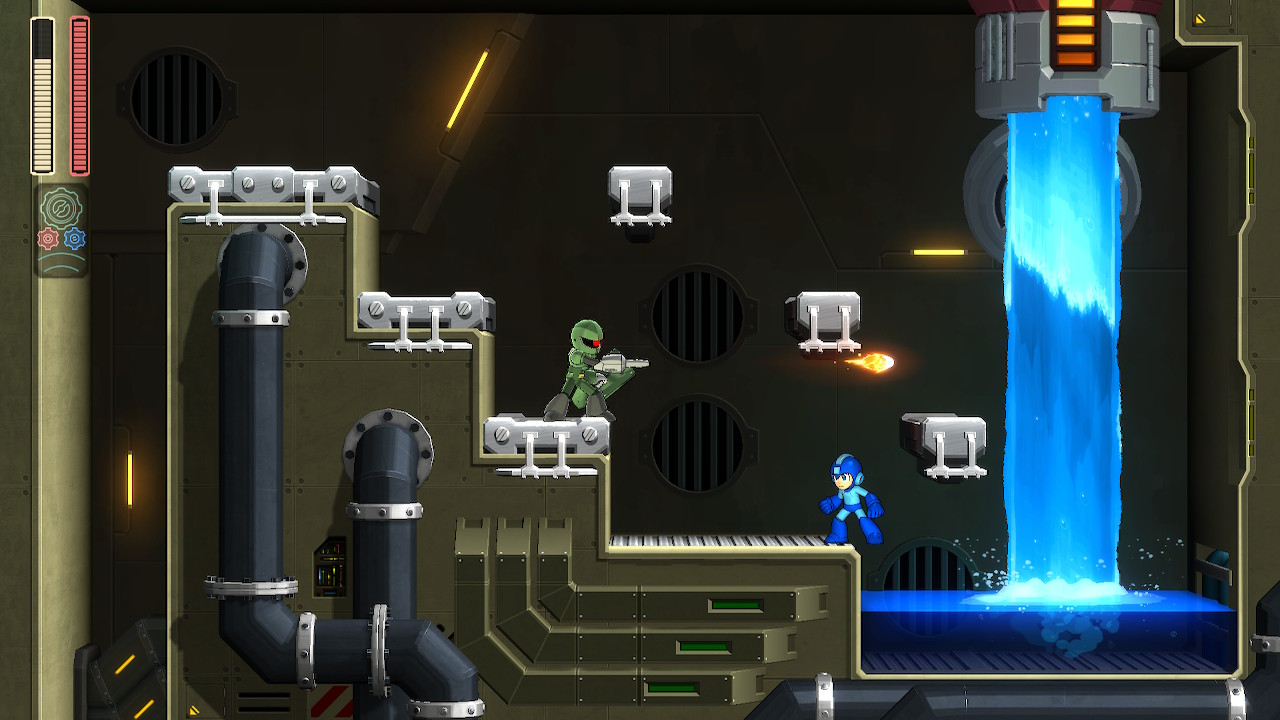

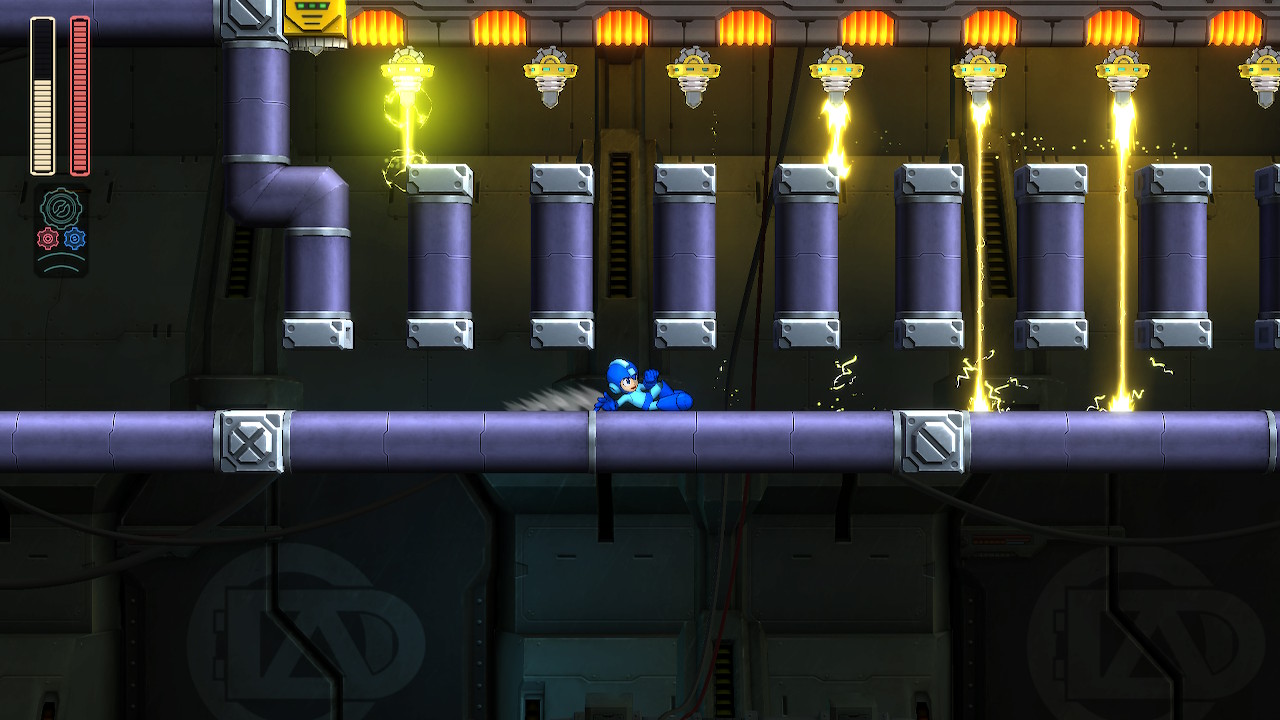

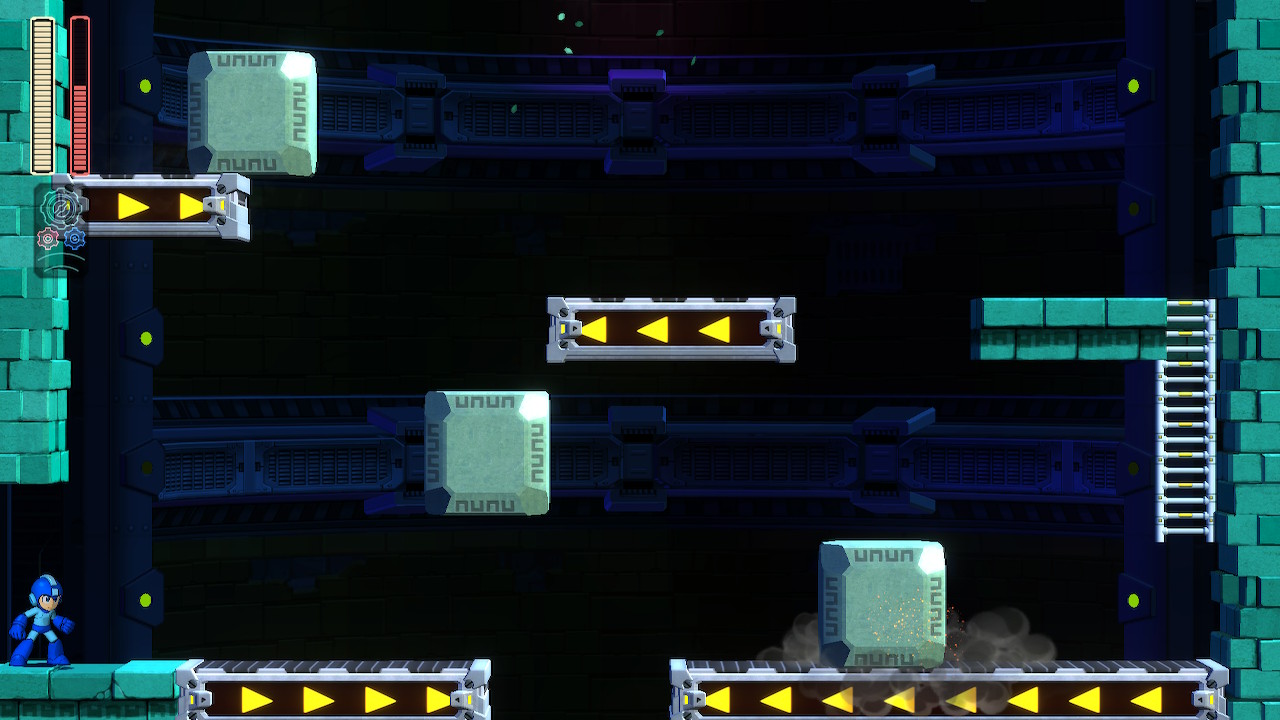

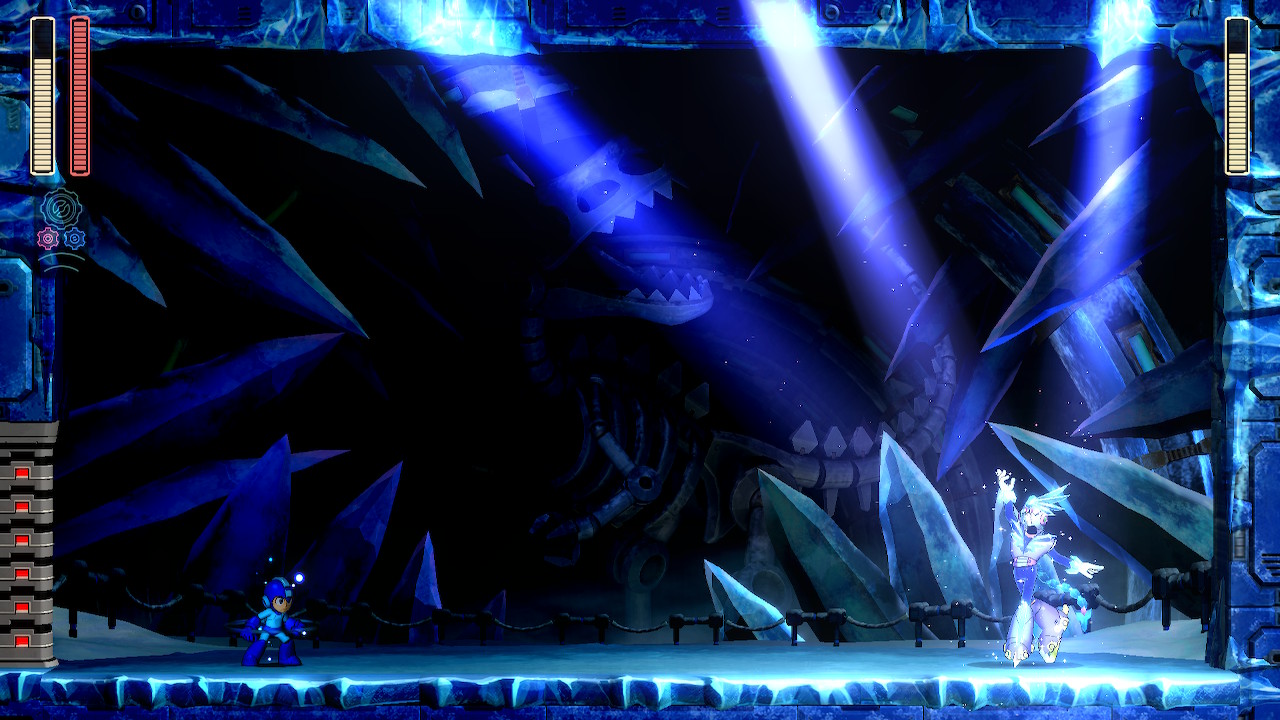

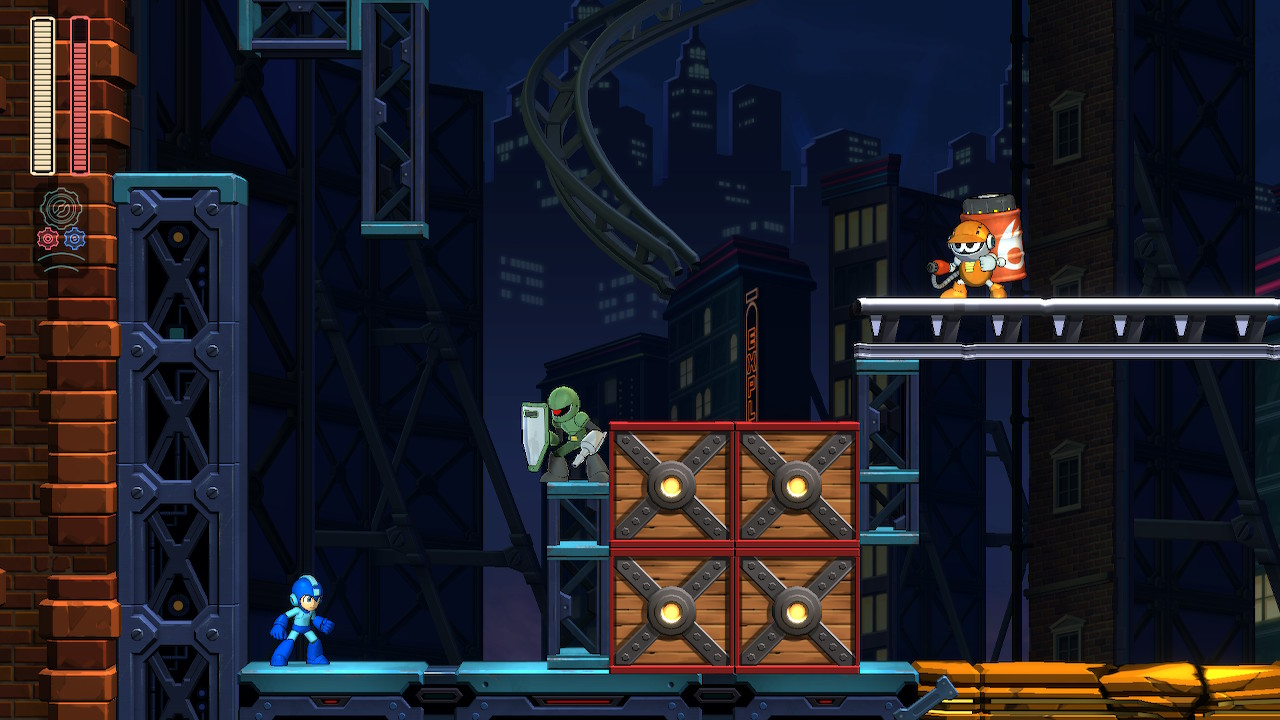

Just to be clear up front, I am playing these games in the Mega Man X Legacy Collection for the simple reason of convenience when gathering screenshots. If something looks different from how you remember it on actual hardware, that’s why. (I have played all of these games on actual hardware, though.) Oh, and don’t judge me too harshly for the state of my health bar. It’s very difficult to play and take screenshots at the same time!

Also, as I dip my first tentative toe into the swirling mass of bullshit that is the Mega Man X series storyline, I’ll say that things are clear and effective enough up front. However, as the series progresses and the games descend into nonsense masquerading as lore and backstory, I’m going to lose my grip on whatever the living fuck is meant to be happening. Go easy on me when I get things wrong, because there’s very little that can be gotten right.

Anyway!

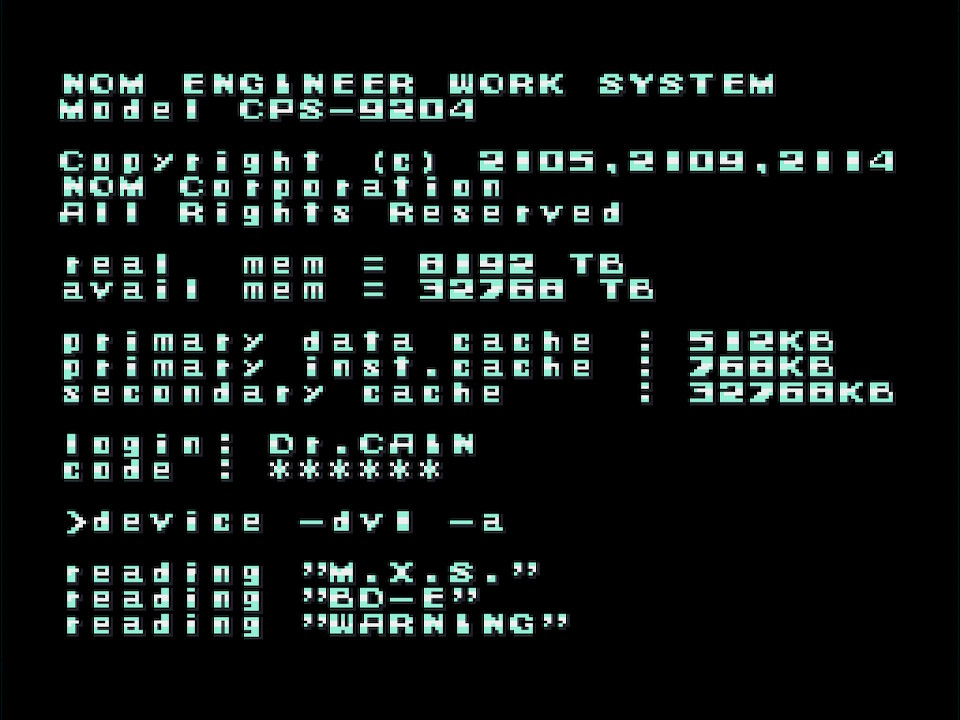

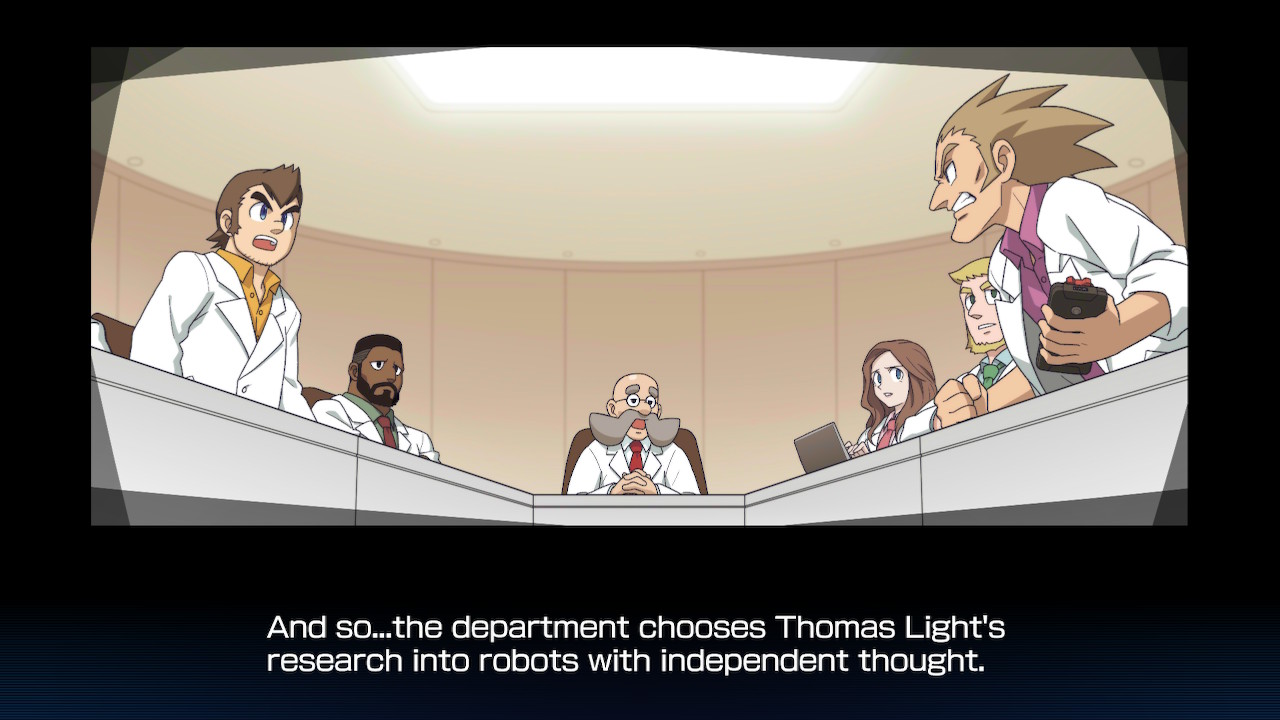

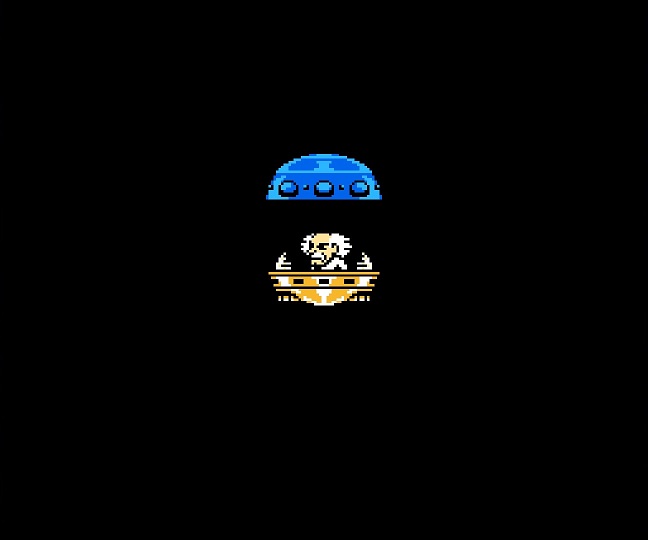

The first thing we see when we load up the game — before actually entering the game — is an intro sequence from Dr. Cain’s point of view. We won’t meet him officially until the next game, but Dr. Cain operates some kind of computer interface to learn about a robot he discovered called X, sealed away in some kind of capsule by the robot’s creator, Dr. Light.

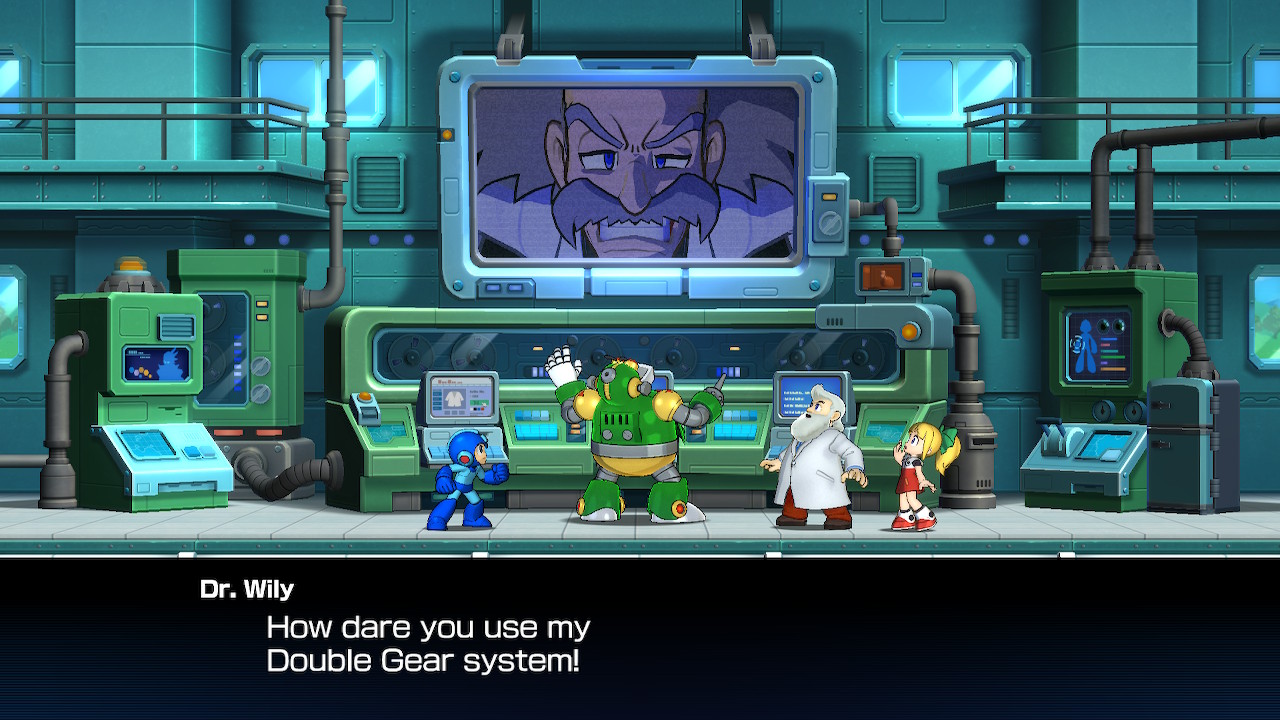

Dr. Cain also reads a warning (messagefromdrlight.docx) that explains that X was an experimental new kind of robot with “an innovative new feature — the ability to think, feel and make their own decisions.” Dr. Light wanted to confirm X’s reliability — dude had created a metric shit-ton of rampaging deathbots by that point so, yeah, good move — and sealed him into the capsule for 30 years of testing. According to Dr. Light’s signature on the document, this happened September 18, 20XX.

Dr. Light points out in the warning that he himself is unlikely to live that long, and so he implores whoever finds X to confirm his reliability before activating him, lest Dr. Light’s creation lead to another generation of rampaging deathbots.

In 21XX, Dr. Cain discovers X and activates him, allowing Dr. Light’s creation to lead to another generation of rampaging deathbots.

This game’s English localization refers to the robot as Mega Man X, but he’s really just X, and that’s how I’ll refer to him in these reviews for the sake of distinguishing him from Mega Man. Anyway, from here, we need to step into inference and material gleaned from later games to understand what’s going on.

Dr. Cain — and presumably other scientists who benefit from the discovery of Dr. Light’s work — learn from X and create Reploids, which are basically new robots that replicate the technology and programming of X. By the time Mega Man X begins, Reploids are all over the place, and a number of them have turned from being helpful to hurtful, much as Mega Man’s initial set of villains were good robots who went bad.

Things are slightly different, though. Nobody took control of the robots here, as Dr. Wily did 100 years or so ago. Instead, they contracted a computer virus that turned them into Mavericks. These aren’t evil robots, in other words; these are sick robots.

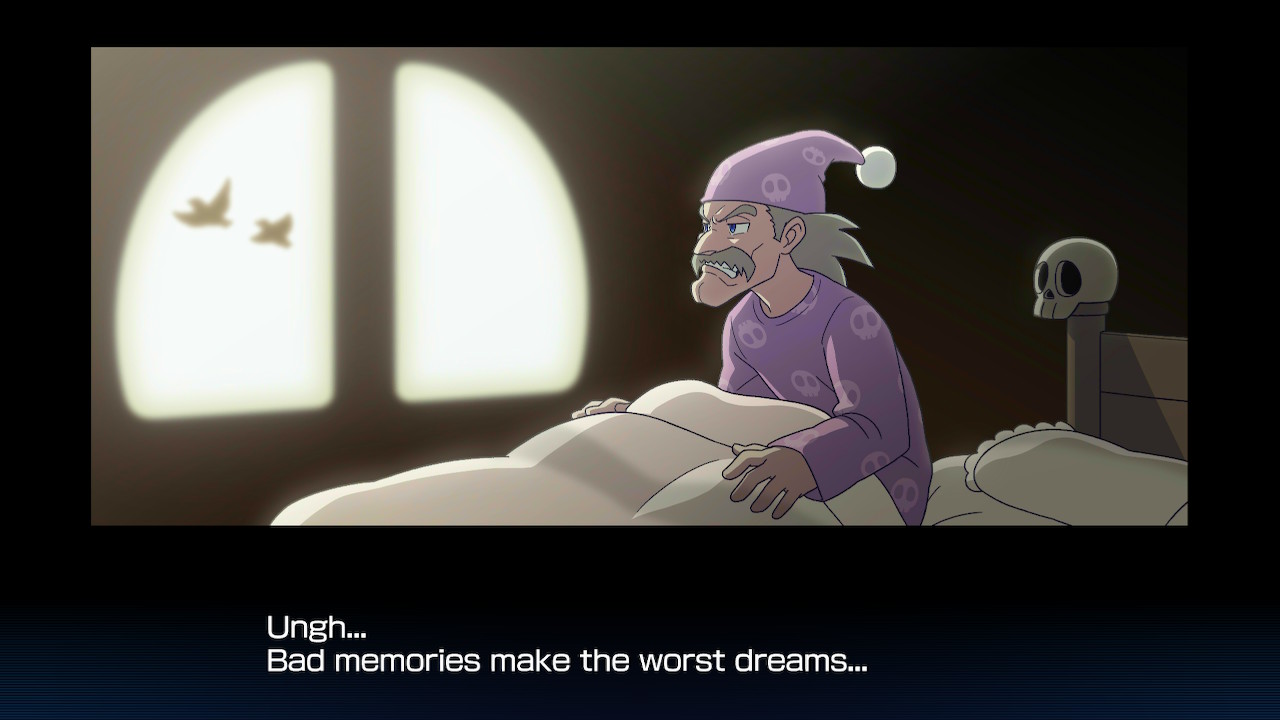

A Reploid named Sigma led a team of Maverick Hunters, who essentially tracked down and neutralized any Mavericks. He was good at his job, but ended up contracting the Maverick Virus himself. Now the most powerful Maverick Hunter is the most powerful Maverick, and X sets out to stop him.

Again, none of that is spelled out in Mega Man X, but we’re given enough information to largely understand who we are and why we’re fighting. Also, having to infer bits of the backstory is perfectly reasonable. Less reasonable is having to infer bits of what’s happening right now in this story, but so be it.

I like the idea that Sigma is a real threat due not only to his power, but due to the fact that he has formal leadership experience. Sigma going nuts and killing everyone is a problem, sure, but the fact that he learned how to lead squads of robots on the side of peace means that his new position leading squads of robots on the side of war poses a genuine crisis. Mankind no longer just has to deal with Mavericks as individual threats; they must deal with Mavericks as an organized force of destruction.

X is still choosing a boss from a list of eight and then heading out to kill it, but this backstory recontextualizes what’s happening; Mega Man took out a boss and then took out another boss several times over. X, by contrast, is gradually weakening a conquering army.

All of that is good, but the intro raises a fascinating question: If the innovation X represents in the field of robotics is the ability to feel and make decisions, then could Mega Man have ever actually been a hero? Or was he just a machine, doing what he was told to do? If Mega Man had been built or purchased by Dr. Wily instead, would he have been just as quick to fight for that side of the conflict?

This isn’t hugely important — again, Mega Man X has incompatible continuity with itself, let alone with Mega Man proper — but I do find it interesting to think about. “Mega Man didn’t have the ability to make decisions” is also a truly mind-blowing retcon when the big gimmick of that entire series was the ability to choose which stages to tackle in which order, ensuring that two players of the games could have — and almost certainly would have — taken entirely different paths through them. (Also, Proto Man’s reluctance to return to and serve Dr. Light does sort of suggest that he would have been the first robot capable of making decisions but, hey, we’ll live.)

The “new” ability of robots to make decisions for themselves does have an extremely wonderful (though very small) effect in Mega Man X: Some of the enemies will pause for a moment to chuckle if they hit you with an attack. That’s completely unnecessary, but what a flourish on the part of this game’s designers. After all, it makes perfect sense that if robots can think for themselves, some large portion of them are going to become absolute dicks.

The intro stage is a Mega Man first. It would become a staple of the Mega Man X series and appear in a few Mega Man games to follow, but in 1993 it was pretty unexpected to be dropped straight into the action, without getting a chance to scope out the bosses ahead of time and decide where you wanted to start. (It’s extra funny that X is the one who can make decisions yet is also the one who isn’t allowed to choose where to begin.)

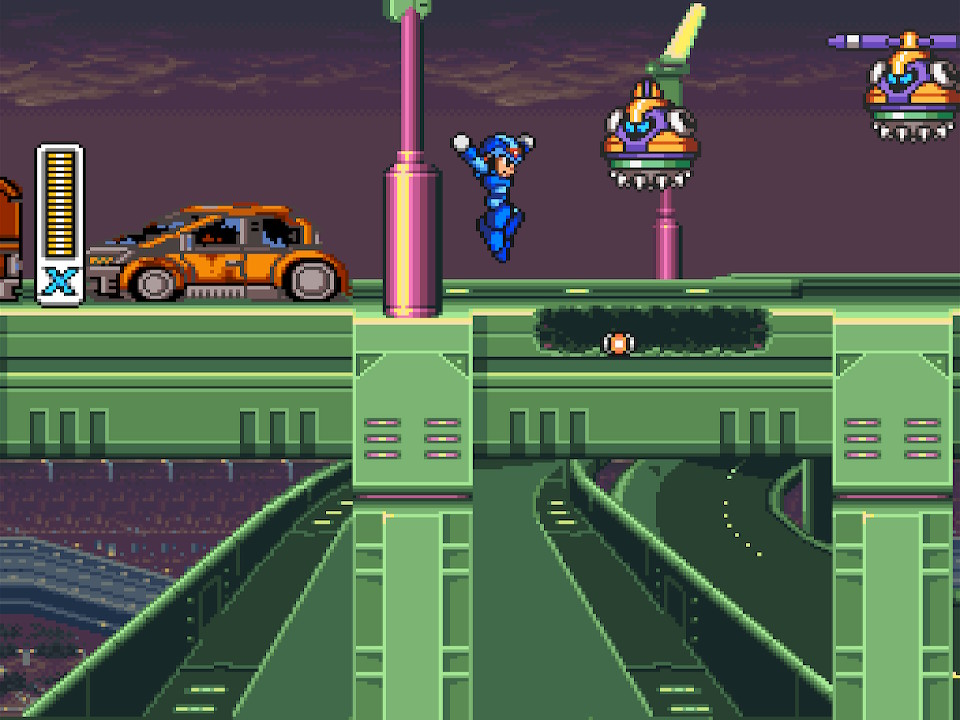

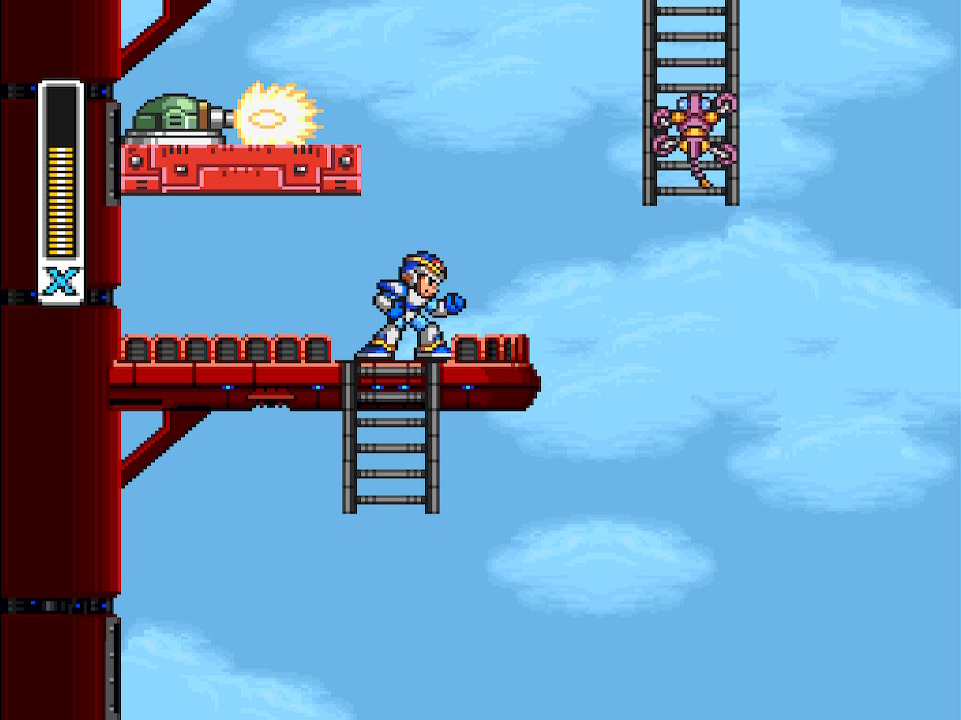

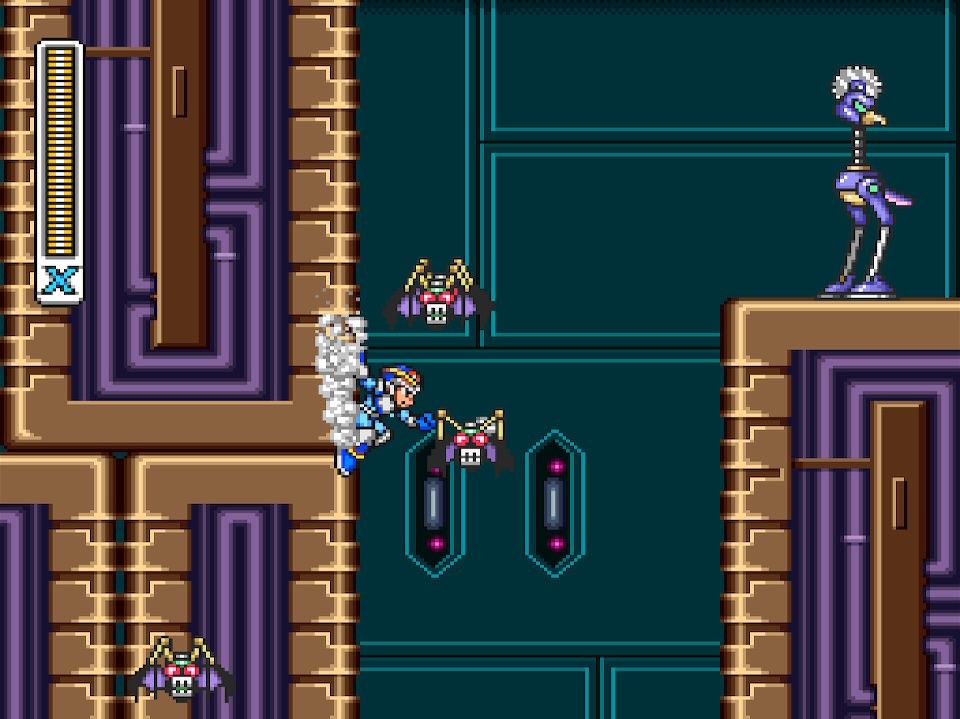

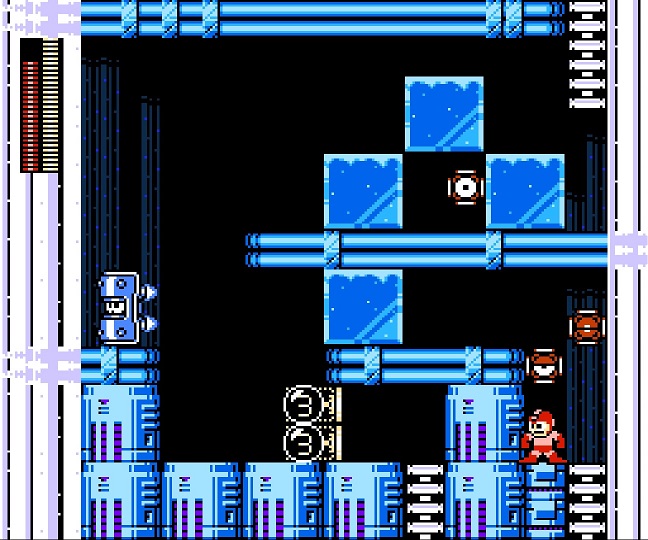

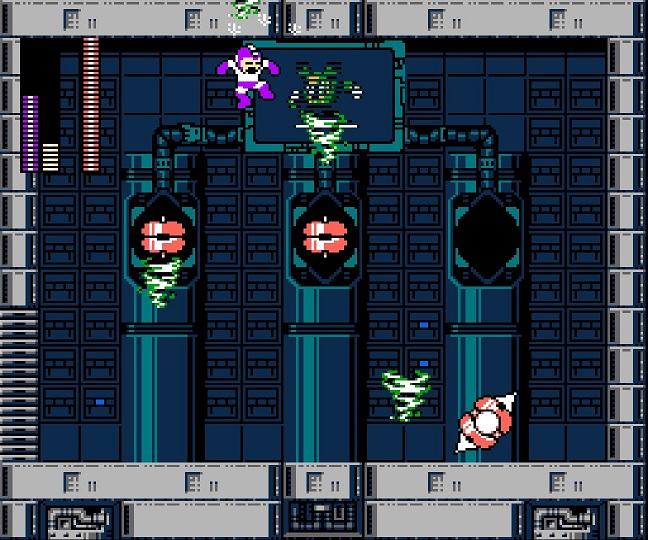

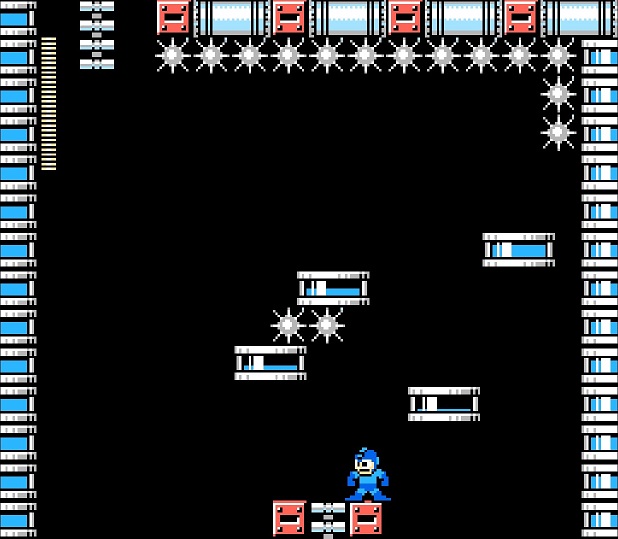

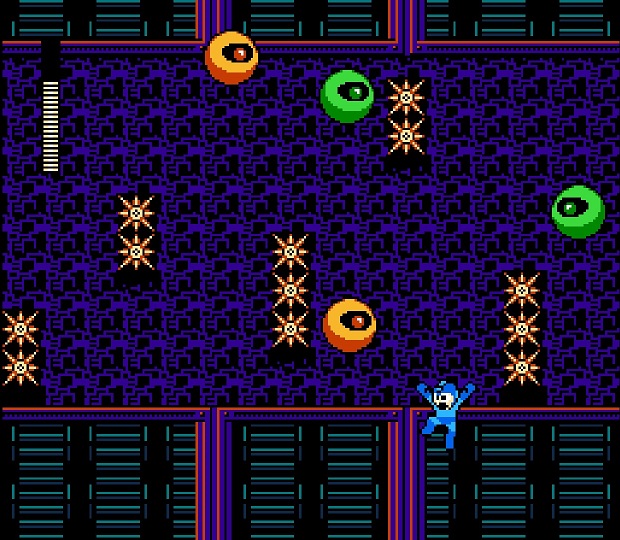

It’s a good level in a few ways. The enemies are weak enough that you’re rarely in real danger, and they’re varied enough that you’ll have to quickly master firing at different heights, firing quickly, firing more powerful shots, and so on. There are also two minibosses who collapse the highway beneath them as they die, forcing you to learn how to use the wall jump.

The wall jump is a massive innovation for Mega Man X, and it’s something that never found its way back into the main series. (It would very much inform the Mega Man Zero series, but that’s a story for another day.) This is a simple mechanic — which I mean as a compliment — but it has huge implications in terms of how the game can be played.

I don’t think Capcom realized just yet exactly how much it shakes up the gameplay. Most of the time, it seems like the developers expect you to simply wall jump for the sake of overcoming obstacles, as you’re taught to do here.

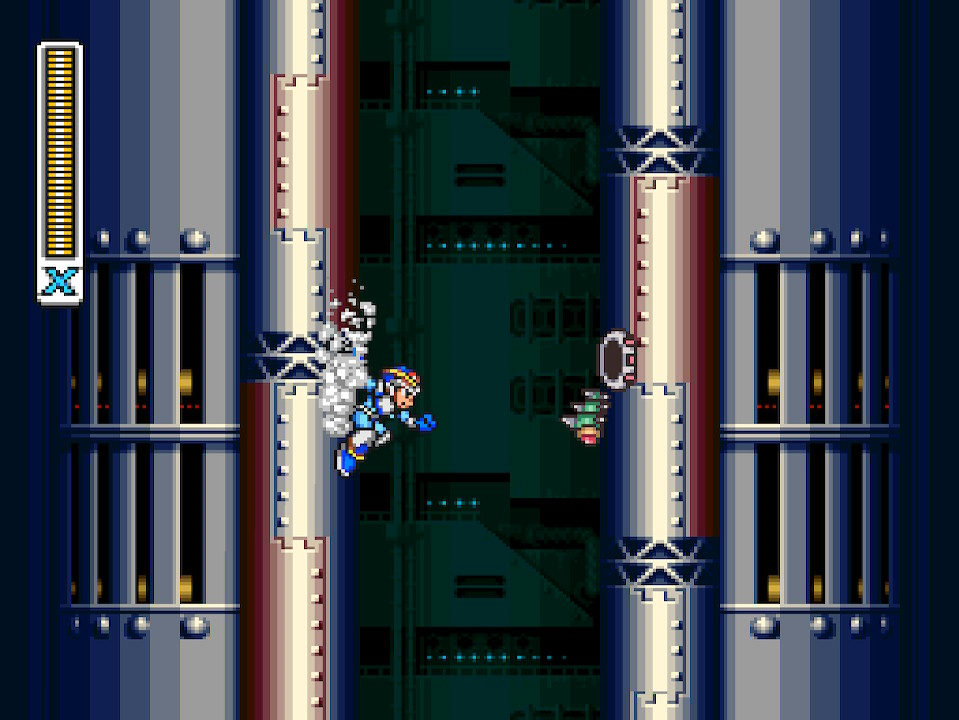

Jump toward a wall and X automatically clings to it, sliding down slowly. Jump while you’re sliding down and you’ll gain height. Repeat the process to scale a vertical wall. That opens up some level design possibilities — and Capcom takes advantage of that several times over — but it also opens up combat possibilities, which I don’t think pay true dividends from a design perspective until later games.

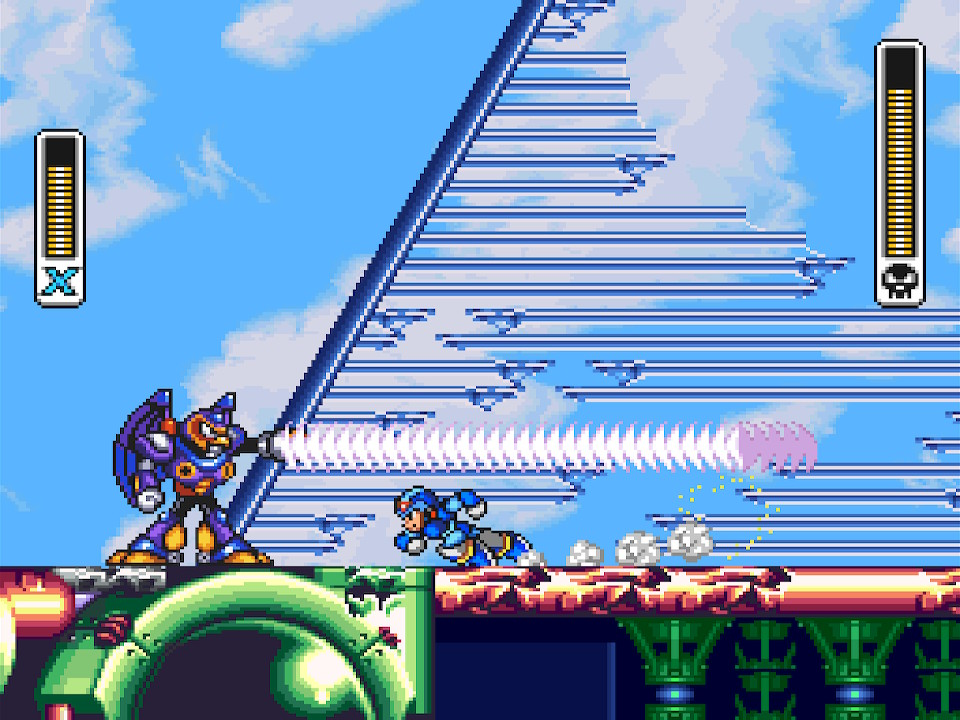

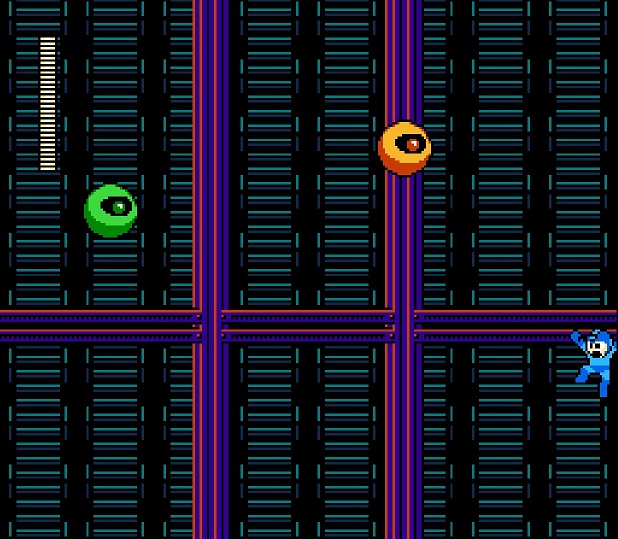

Basically, any time there’s a vertical wall, you’re no longer limited to how high you can jump; you can climb all the way to the ceiling whenever you like. Where does this matter most? Well, during boss fights, where you always (with the exception of Storm Eagle) have tall vertical walls to scale. Whereas Mega Man could hop over and slide under projectiles, he was still always at the mercy of any given Robot Master and its attacks. Mega Man would far more often have to react than act.

X, however, thanks to the wall jump, has infinitely more mobility than any of the bosses in this game, meaning that they are at his mercy. The only thing you have to do as a player is master X’s moveset and get comfortable with climbing. Once you do that, it’s the Mavericks who will be forced into reacting. Instead of needing to master the moves and patterns of eight main bosses, you only really need to master the movement of one protagonist. After all, unless they can fire a projectile that reaches the ceiling, you don’t have to worry at all about what they’re doing down there.

That’s neither good nor bad; it’s just a fact. Climb into the upper corner of a room and wall jump quickly enough to stay there and few Mavericks will even be able to hit you. They’re simply not equipped to handle that level of agility, and they’ll almost always have to rely on you fumbling the timing and falling back down to where they can reach you. If you don’t fumble that timing, however, you will always have the advantage. You can choose to drop down only when it’s safe, fire a few small shots or one charge shot, and then hop right back up where they can’t reach you.

Perhaps Capcom figured that few players would bother learning the movement mechanics well enough to turn them into such a significant advantage. Perhaps Capcom didn’t realize it was even possible. It’s hard to say, but the set of Mavericks in this game are absolutely hamstrung by your newfound ability to keep out of reach. I don’t see this as a problem — new players won’t master the mechanic that quickly or easily — but I’m certainly pleased to report that Mavericks in later games won’t be quite so exploitable by default.

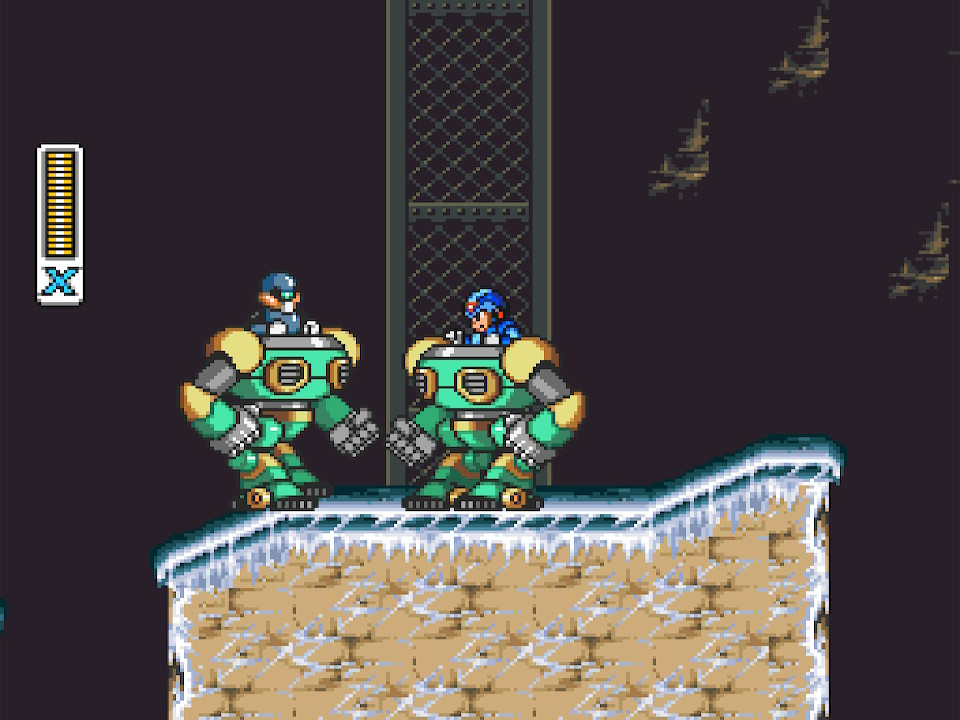

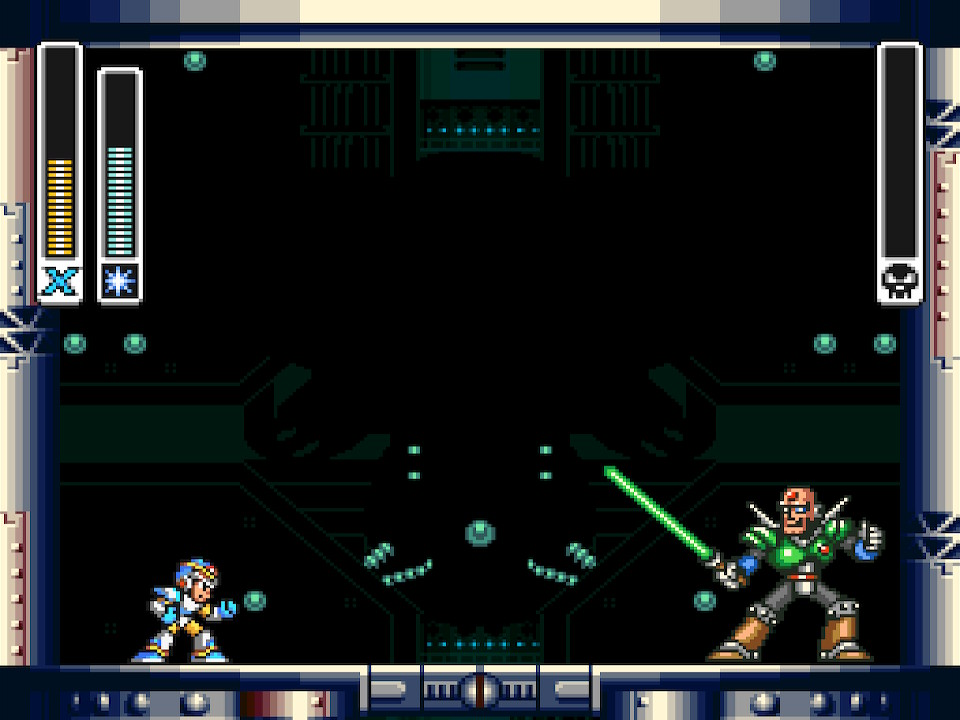

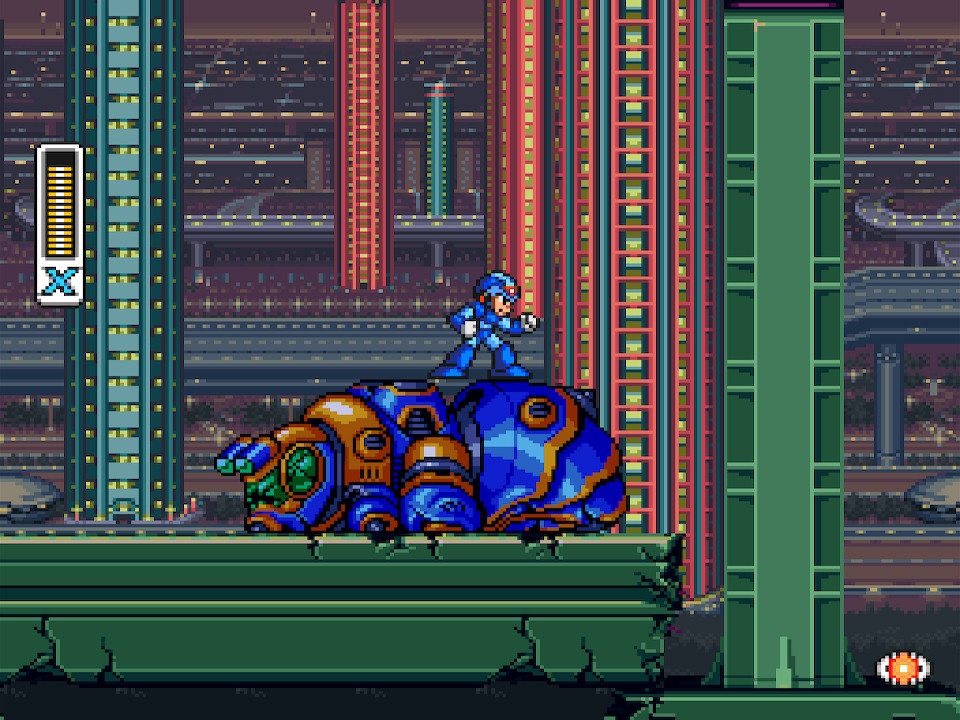

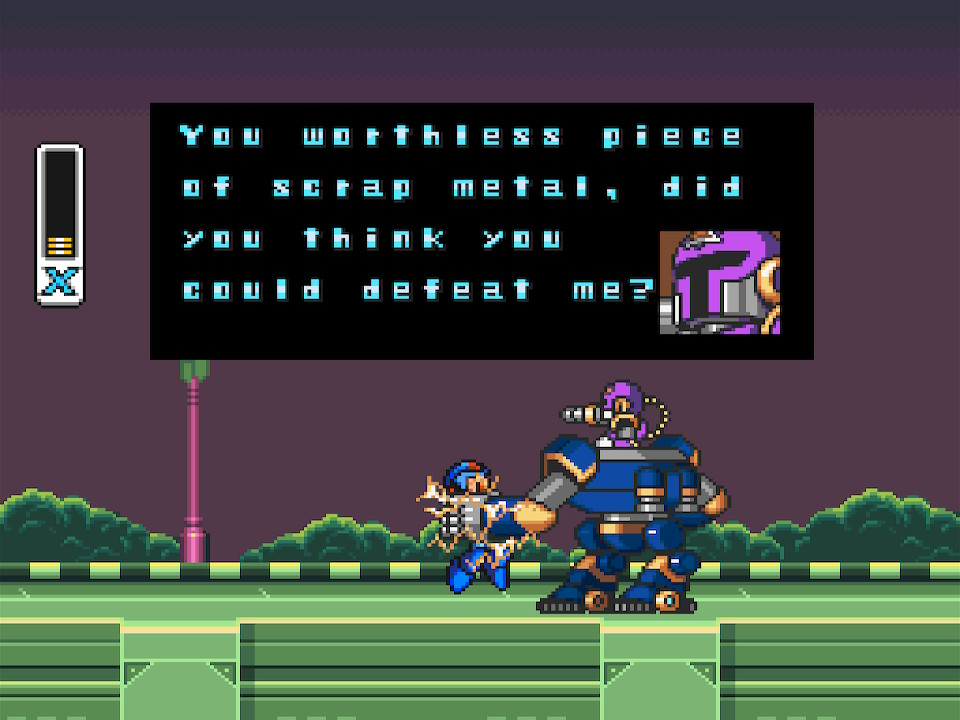

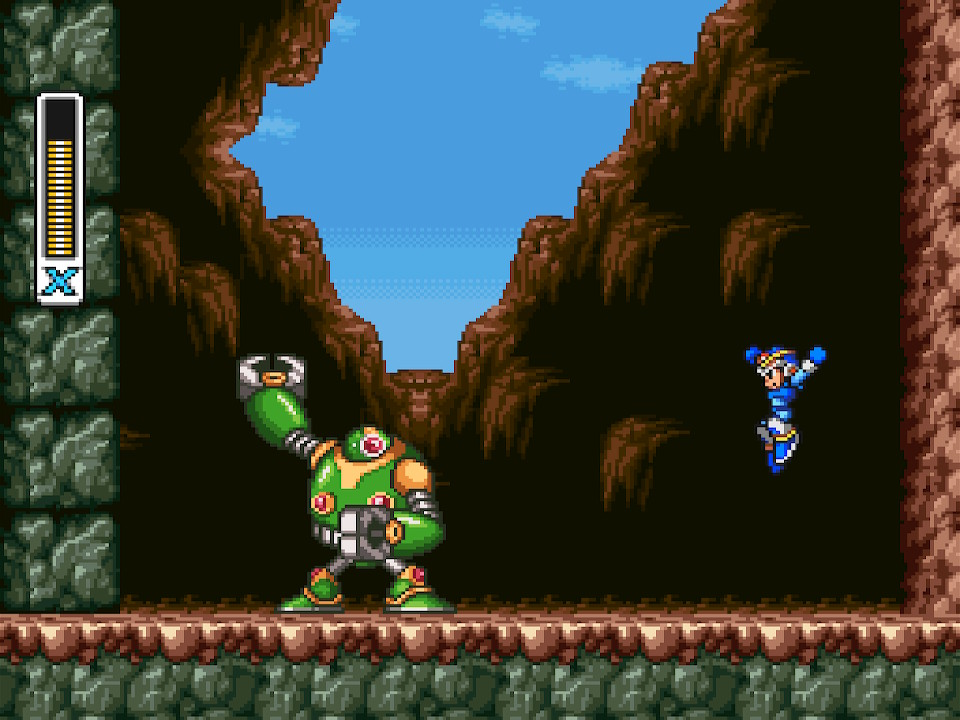

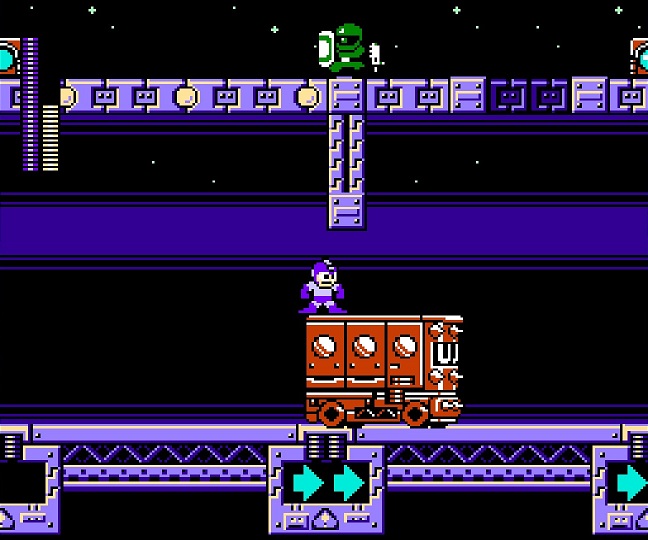

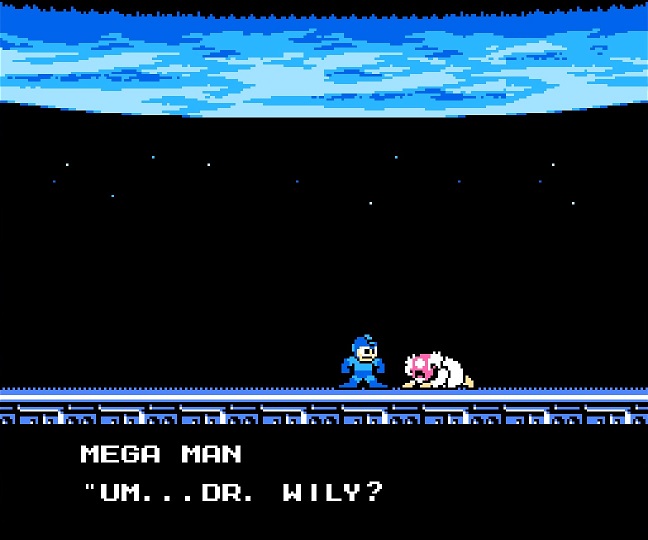

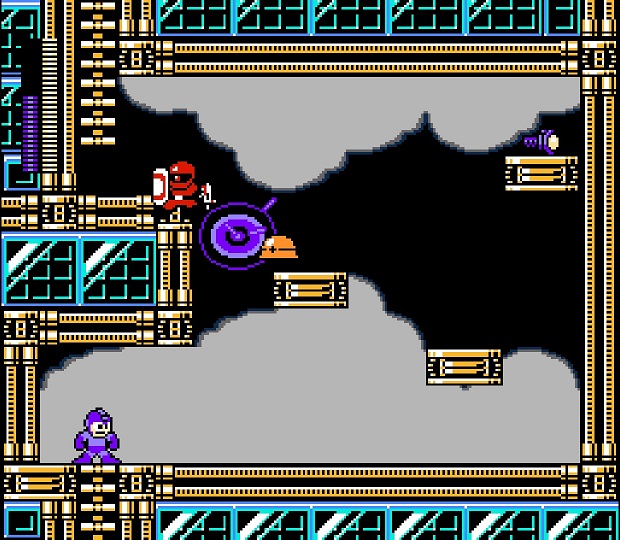

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. At the end of the intro stage, you fight Vile, one of Sigma’s powerful lackeys. He uses Ride Armor — basically a bigger robot body into which you can climb, and which itself will become another series staple — and you are destined to lose the fight.

Vile is bigger, stronger, and more durable than you are, and it’s impossible to defeat him. Maybe you did well in the intro stage. Maybe you didn’t. Either way, Vile leaves you broken and defeated and Zero, an ally X is meeting for the first time, shows up to save your sorry ass.

You are guaranteed to realize the same thing from this scene that X does: You’ve got a long way to go, kid.

Let’s step back.

Mega Man 7 eventually took a few cues from Mega Man X. One of them was the intro stage, which in both games is a broken highway in a city under siege. Both Mega Man and X fight their way down the ruined road, looking very similar to each other, using a very similar weapon to each other, and at the end they each encounter the Big Bad’s highest-ranking crony, who attempts to put them in their place.

In Mega Man 7, though, you can win the fight. It’s Bass there, and if you fight carefully enough, you can overpower him. You certainly can lose to him, and easily, but you don’t have to lose to him. You can humiliate him just as much as he intended to humiliate you, sending him home to lick his wounds.

That makes sense. It’s a video game. Play well and win, play poorly and lose.

In Mega Man X, though, you can’t play well at this point. X is physically incapable of subduing Vile. This means something, and it further defines the contrast between that game’s protagonist and this game’s.

Mega Man, basically, was not weak and therefore never felt weak. He was limited only by your own abilities as a player. If you didn’t know what you were doing, he’d die a lot. But if you were good at the game, he was able from the very start to handle anything that the stages, enemies, or bosses could throw at him. He was ready for the adventure. You may not have been, but he was.

X is different. X is not ready, and Mega Man X is the story of X becoming ready, fight by fight, stage by stage, upgrade by upgrade. X is sent into battle, but cannot win. He is doomed to failure, unless he grows, changes, and becomes more powerful.

When Dr. Wily underestimated Mega Man, it was at his own peril. It was because he had an inflated sense of self and refused to accept that he could be bested by a super fighting robot. When Sigma and his loyal troops underestimate X, though, you can’t blame them. X is basically an insect at this point. He might win a few skirmishes through sheer luck or resilience, but he is literally incapable of winning the war.

Dr. Wily felt secure, in other words, because he failed to view Mega Man for what he really was. Sigma feels secure because he views X exactly for what he is.

There’s no real “better” way to design games, of course. I certainly have no problem with the fact that Mega Man never felt weak. However, because he never felt weak he also never felt strong. He operated from the start of each game to the end at the same baseline level of competence. There was no real growth. X feeling weak at the start, by contrast, means that he can feel like a powerhouse by the end, because Mega Man X built itself room for that transition to take place.

This gives each series a different identity. When playing a Mega Man game, you as a player would experience the growth and learn how to overcome challenges. When playing a Mega Man X game, that increase in competence belonged at least in part to the character instead. Both approaches are valid, and Capcom’s attempt at the new approach works brilliantly here.

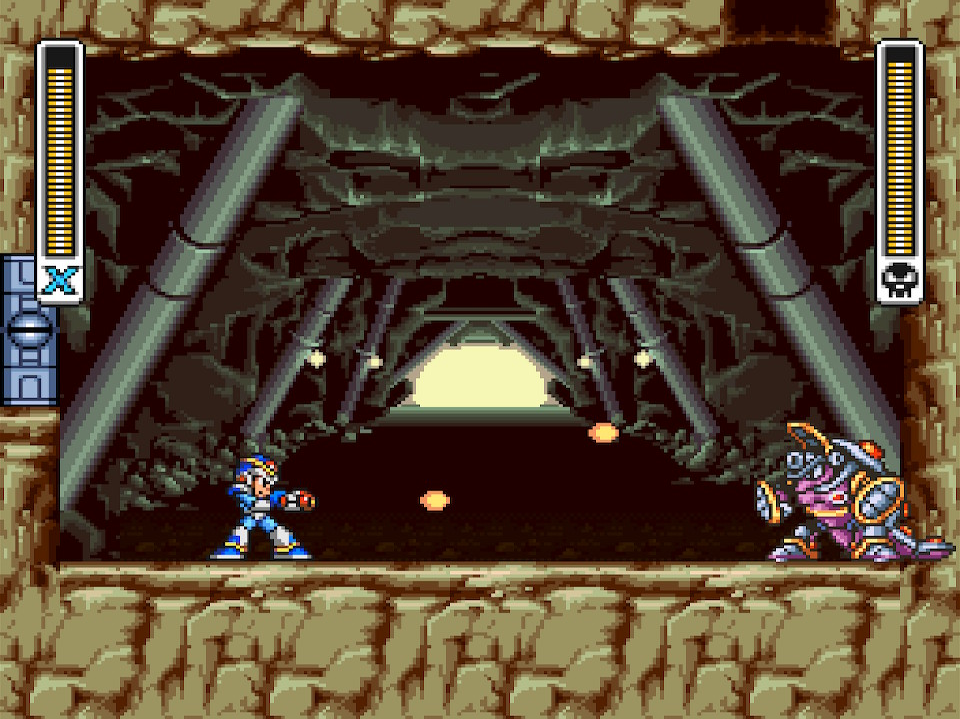

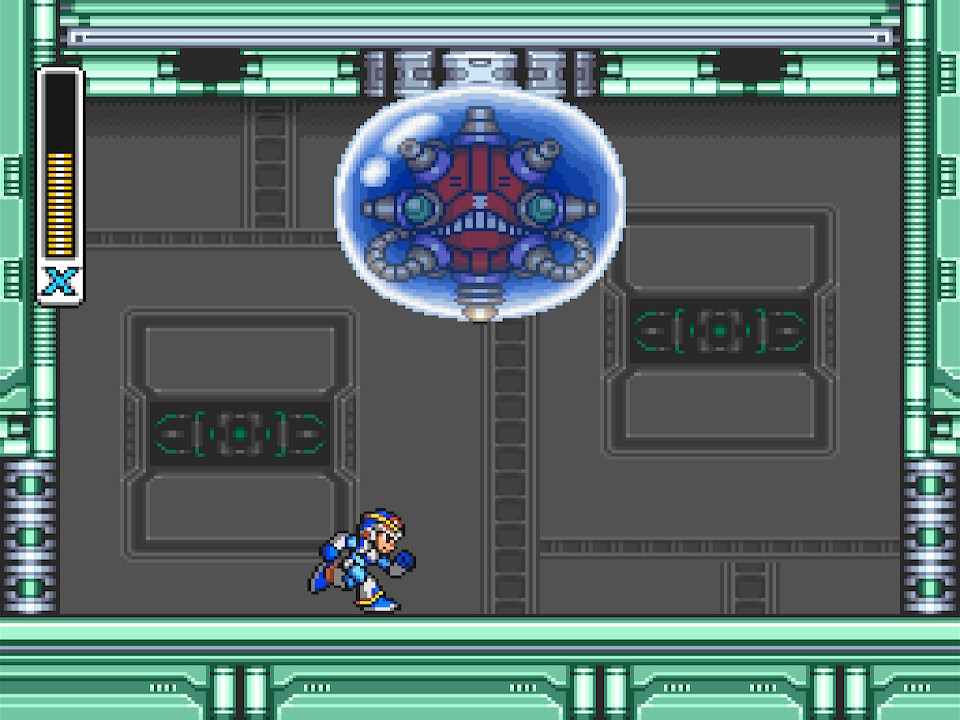

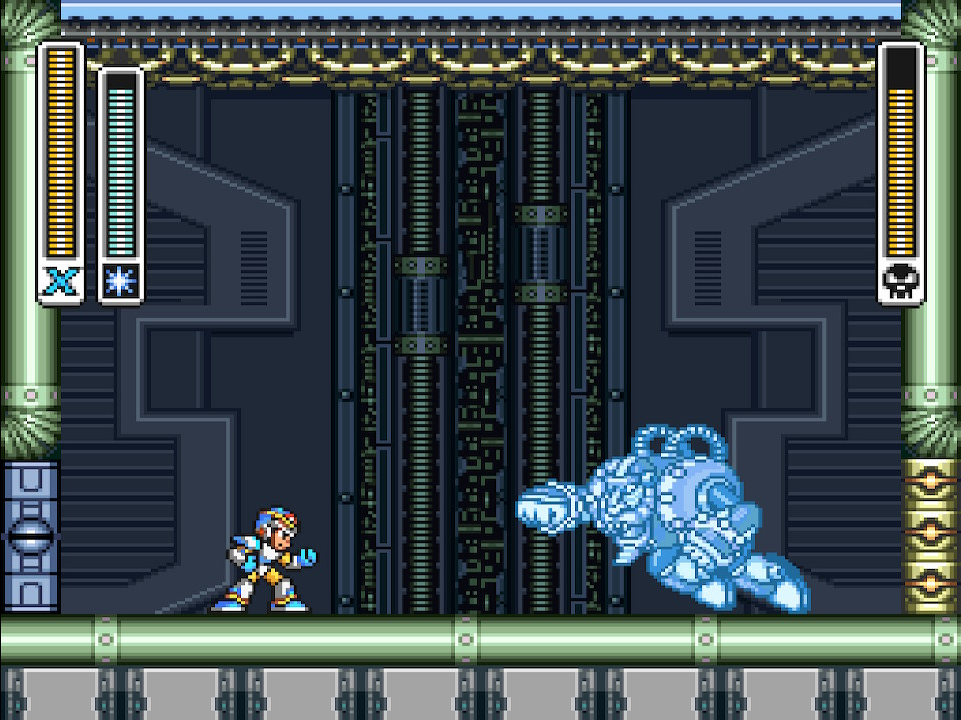

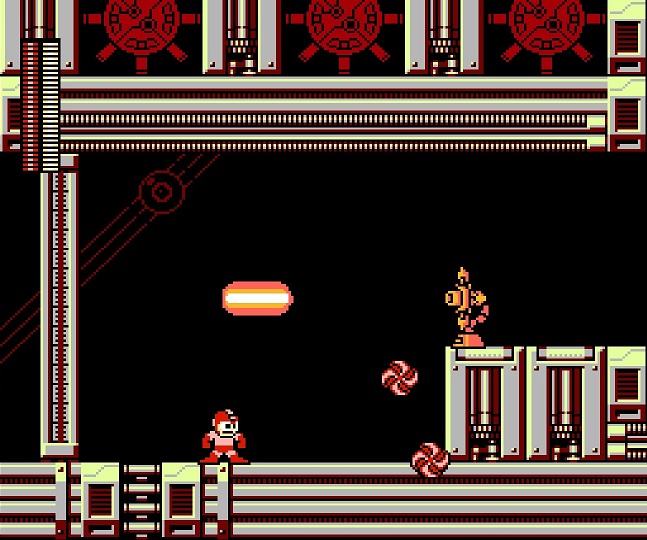

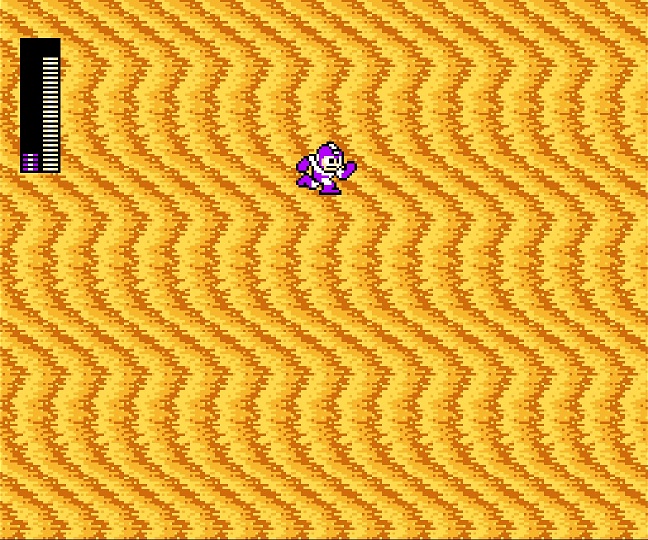

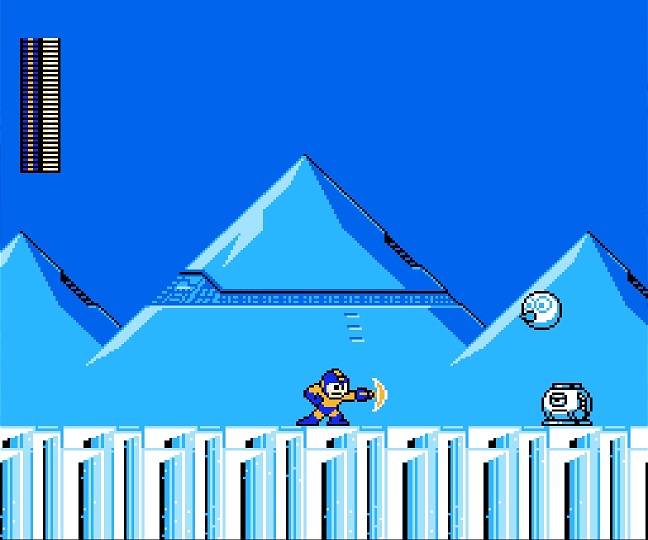

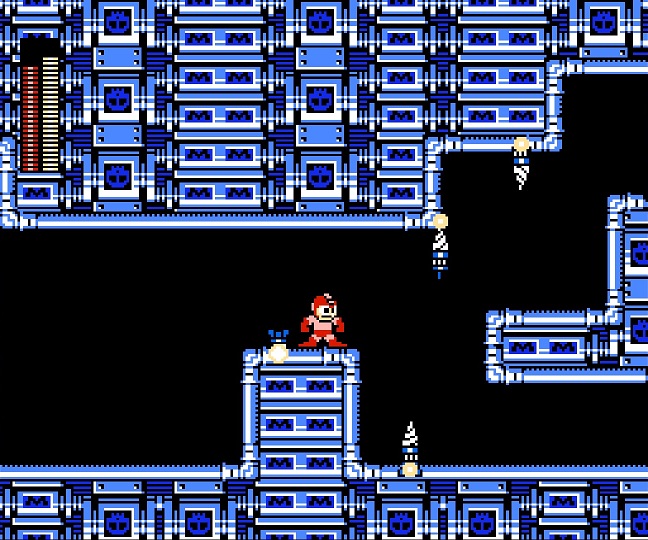

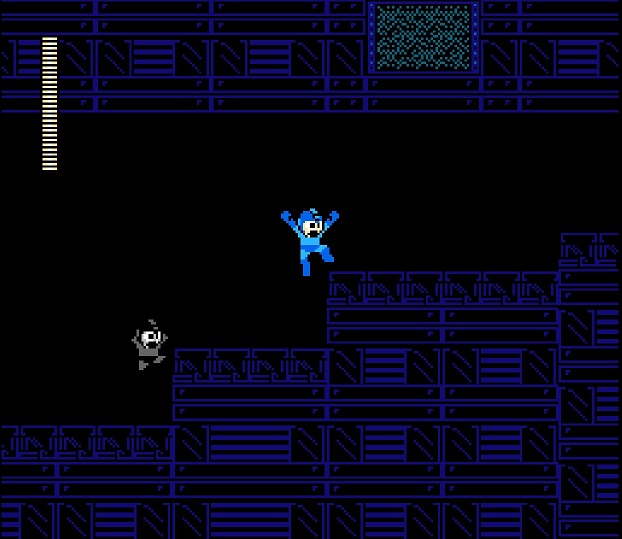

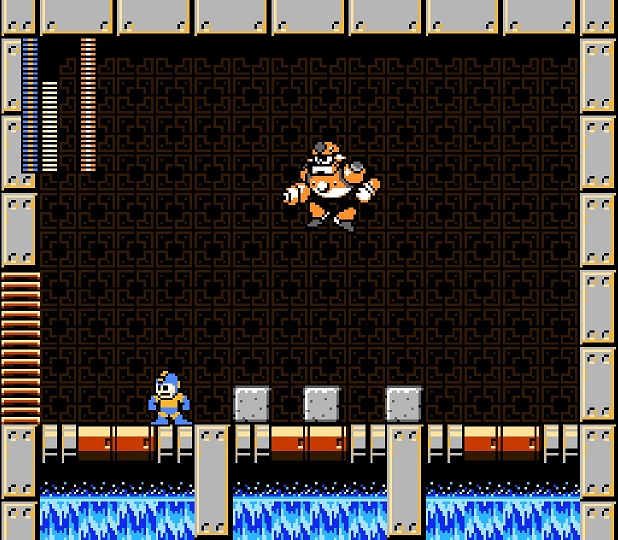

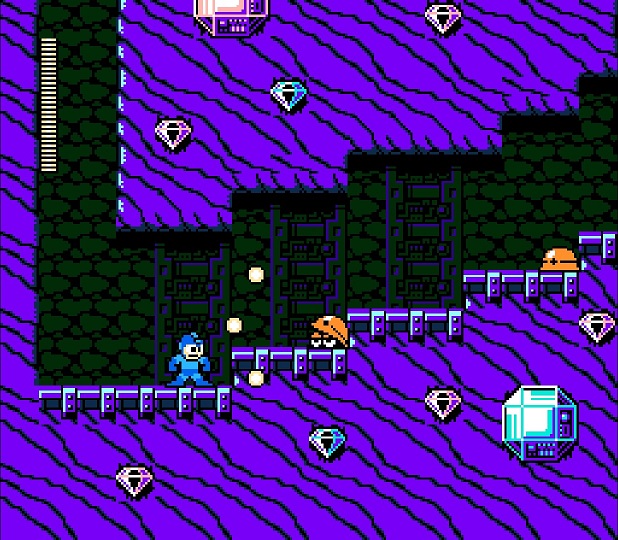

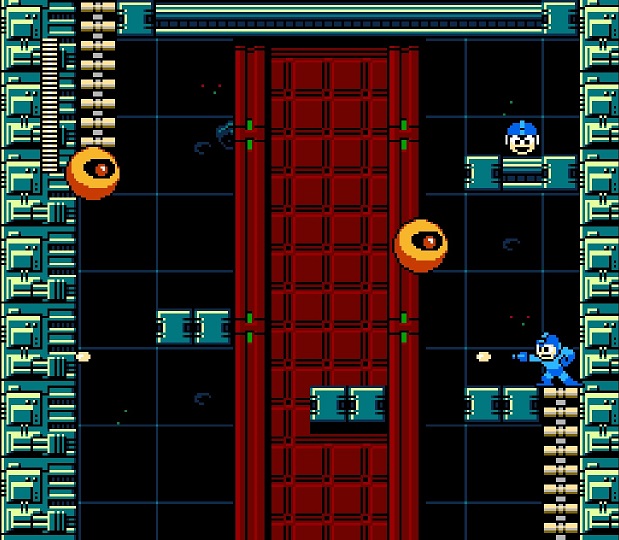

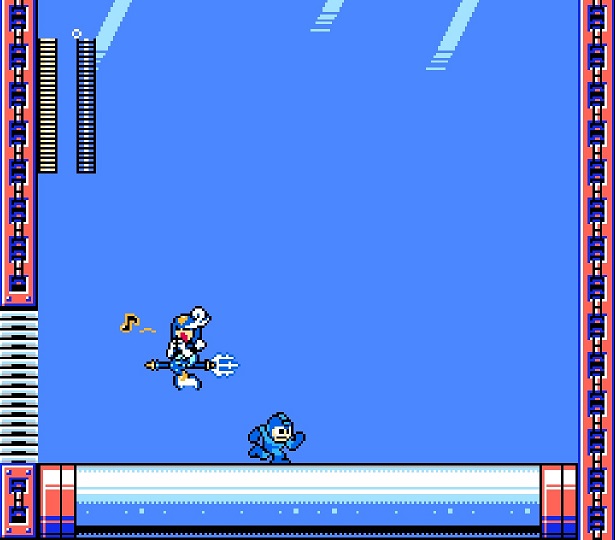

How did they accomplish it? Well, if you look at X’s life bar in the screen shots from the intro stage, you’ll get some idea. It’s absolutely minuscule compared to Mega Man’s…but, hey maybe folks playing the game for the first time might not realize that. Whenever you square off against a boss, though, you’ll see just how much longer their life bar is by comparison. It will be made immediately clear to you just how outmatched you are, and how much harder you will have to work than they will. They can afford to make more mistakes than you can; you’re the weakling.

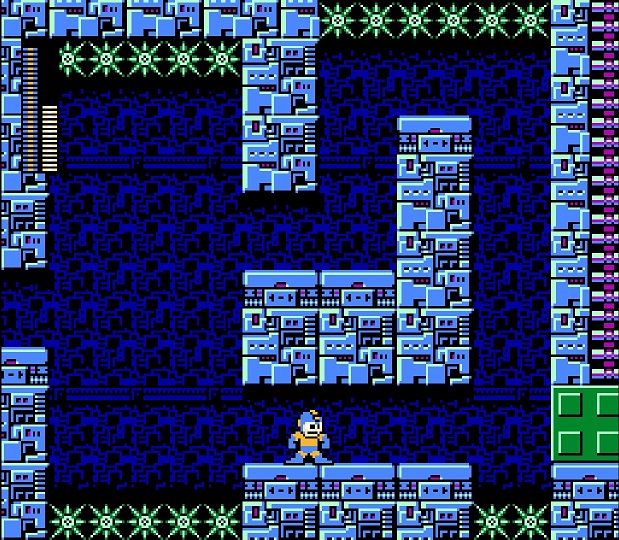

That does a pretty good job of establishing you as being a relatively fragile character, but that’s just the start of the journey. The game is designed to take you gradually from that state to being a fully powered-up war machine.

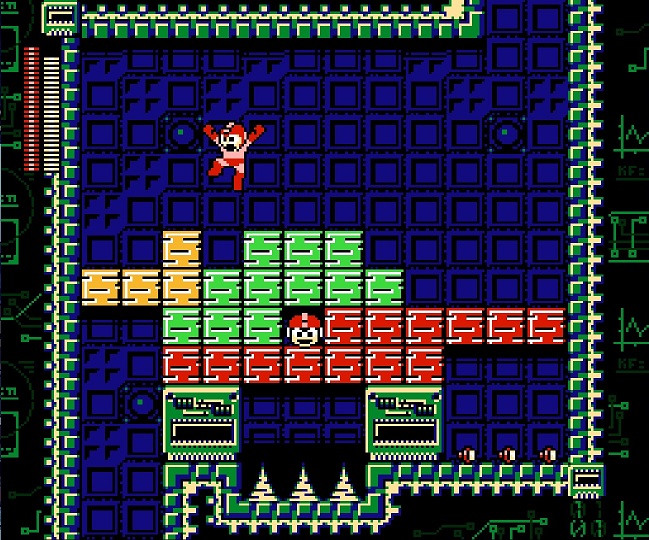

It does this by squirreling away upgrades in each of its main stages. In Mega Man, of course, you would finish a stage and receive a new weapon, which was nice, but it never changed the fundamental way in which you interacted with stages or how durable or powerful you were. Sometimes you’d snag a utility or two along the way, but usually you didn’t, and even those just helped you avoid a platforming challenge or two.

Here you still get a weapon for defeating a Maverick, but the empowerment comes from exploring those Mavericks’ stages. You can find a heart tank in each of the levels, which extends your life bar just a little bit so that you can take more damage. You can find four subtanks, which allow you to replenish your health. (You fill these by picking up health when you don’t need it, and you can reuse the subtanks as many times as you like, both of which are very welcome changes to the one-use-only E-tanks of Mega Man.) You can find more of Dr. Light’s old capsules, each of which upgrades some aspect of X’s technology.

Because you find those things by exploring rather than fighting, you are not only encouraged to engage with the main levels in a new way — and probably repeatedly — but you are able to increase your abilities at a steady pace, even if you aren’t able to defeat any of the bosses yet. If you’re really struggling, you can visit a stage, find whatever upgrades you can, die, and then try another, where you might find even more upgrades. You retain your items upon death, which means that you’re no longer stuck if you’re struggling to defeat a boss; you can still seek out other ways to give yourself an edge.

The feeling of gradual empowerment is sincere. It’s the main theme of the game, in fact, and it’s presented, explored, and felt through gameplay. Mega Man relied on raw skill alone, but Mega Man X offers a bunch of small ways to tip the odds in your favor as the protagonist grows into a more capable hero. X’s journey is one of significant and lasting growth.

There’s a bit of a strange imbalance here, though, when it comes to how these upgrades are distributed, and I can’t tell if it was deliberate or accidental.

I’ll explain. There are eight main stages and eight heart tanks, so each stage gets one heart tank. That’s expected and makes sense. Then there are four subtanks and four Dr. Light capsules, so you’d think that each stage would get one of those two things as well. That would also make it easier for folks to remember which stages they’ve “cleared” and which still have an upgrade or two left to discover.

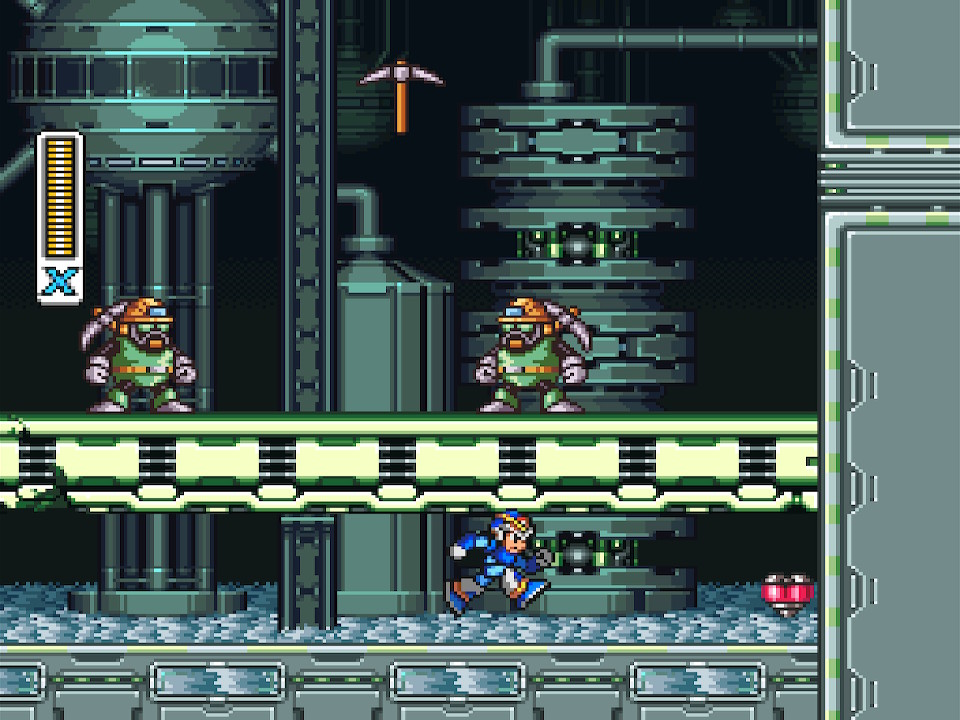

In practice, though, Flame Mammoth and Storm Eagle get one each of all three upgrades. Boomer Kuwanger and Launch Octopus — or Octopardo, as he liked to be called — only get a heart tank. There’s certainly no rule of game design that says that the distribution of upgrades must be even, but I’m not sure why a decision was made to keep it uneven, when that would only make it difficult for players to intuitively understand when they’ve found everything.

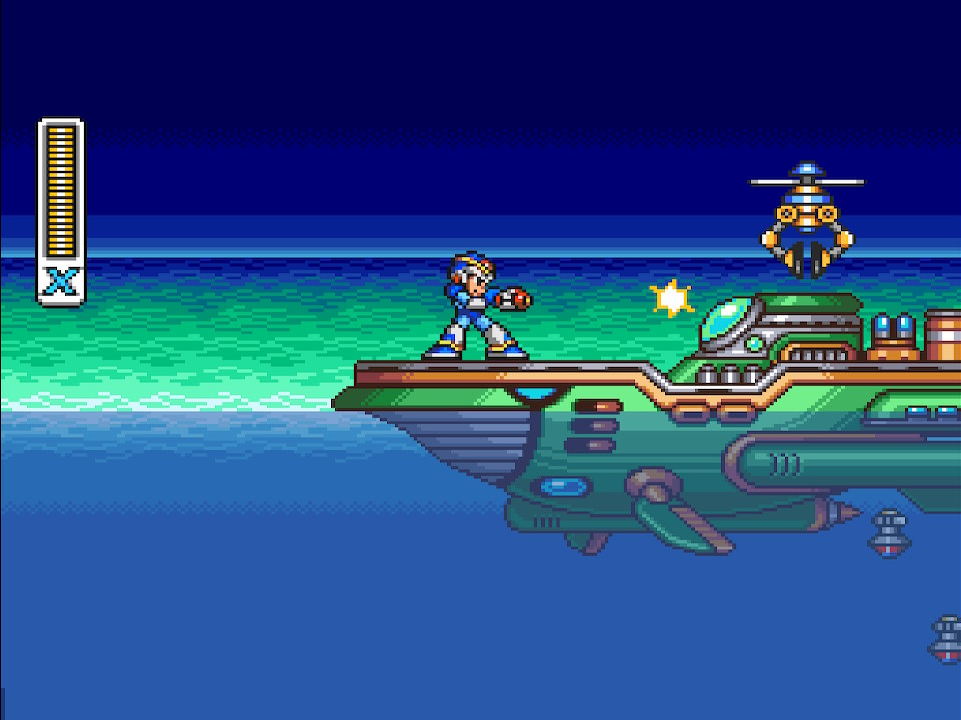

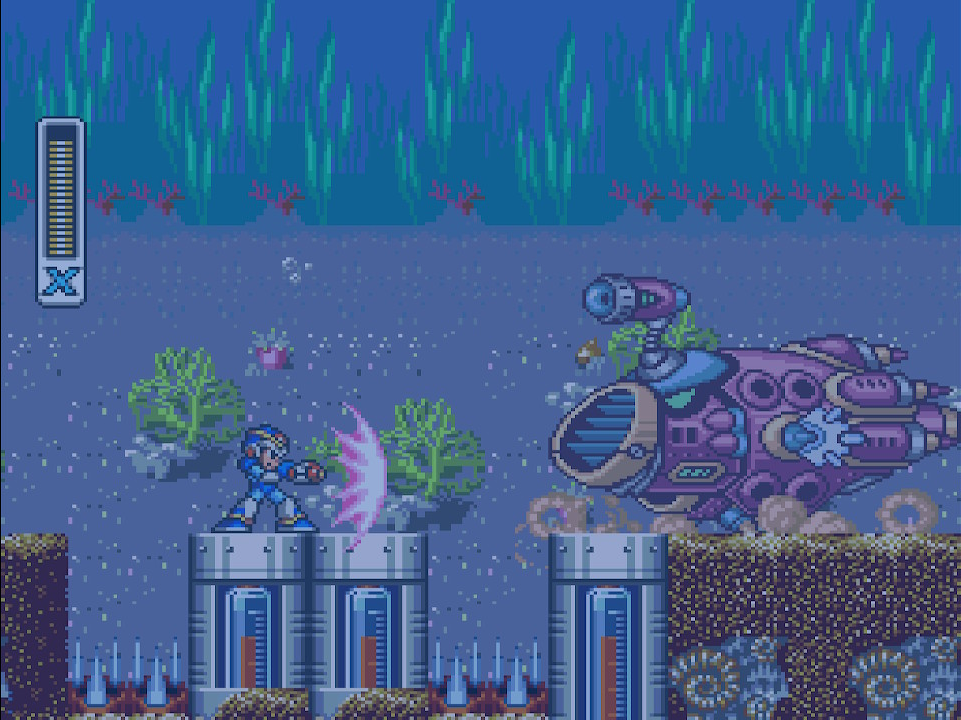

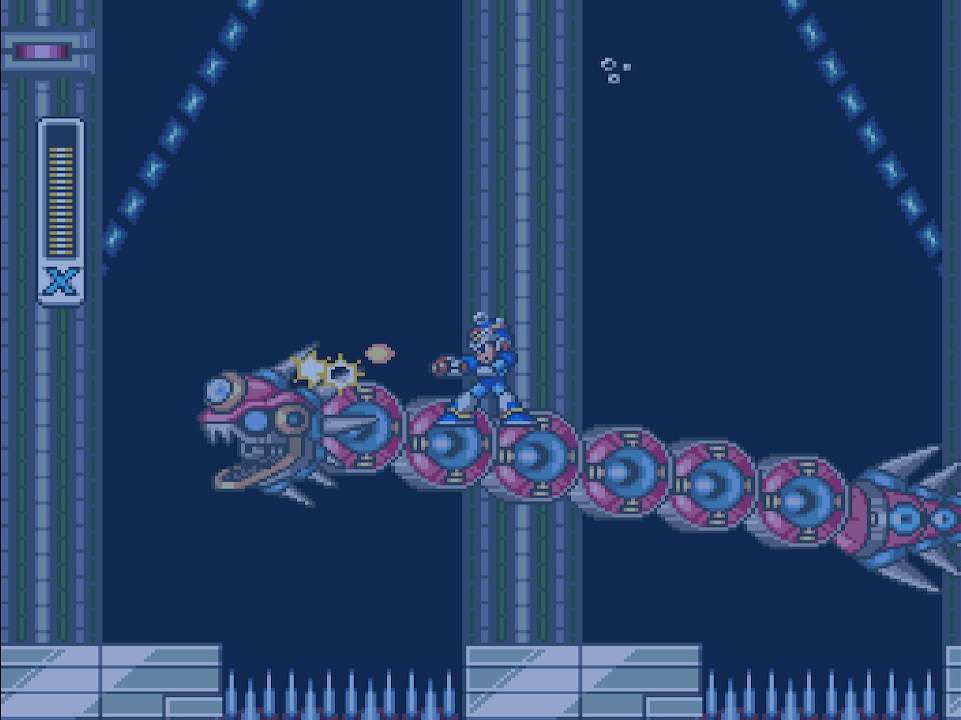

Also, Launch Octopus’ stage feels weirdly long and sprawling to contain only one upgrade; there are a whopping five minibosses here — some of them being optional — so for one upgrade alone to be hiding here, it feels oddly lopsided.

As long as we’re on the subject of upgrades, let’s talk about the Dr. Light capsules, because these introduce their own problems.

The most obvious one has to do with the narrative and, to be fair, is something that will only be a problem as the series progresses.

Right, so, Dr. Light wasn’t certain that X would be “reliable,” hence the three decades of testing. Dr. Light also wasn’t certain that he himself would live long enough to verify X’s reliability. We can therefore infer that these four capsules scattered around contain upgrades that Dr. Light would have given to X anyway, assuming X came through testing okay and didn’t have to be destroyed or something. These capsules, basically, were a way for Dr. Light to prepare upgrades for the robot, but not install them, in case something went terribly wrong and X turned out to be insane or murderous.

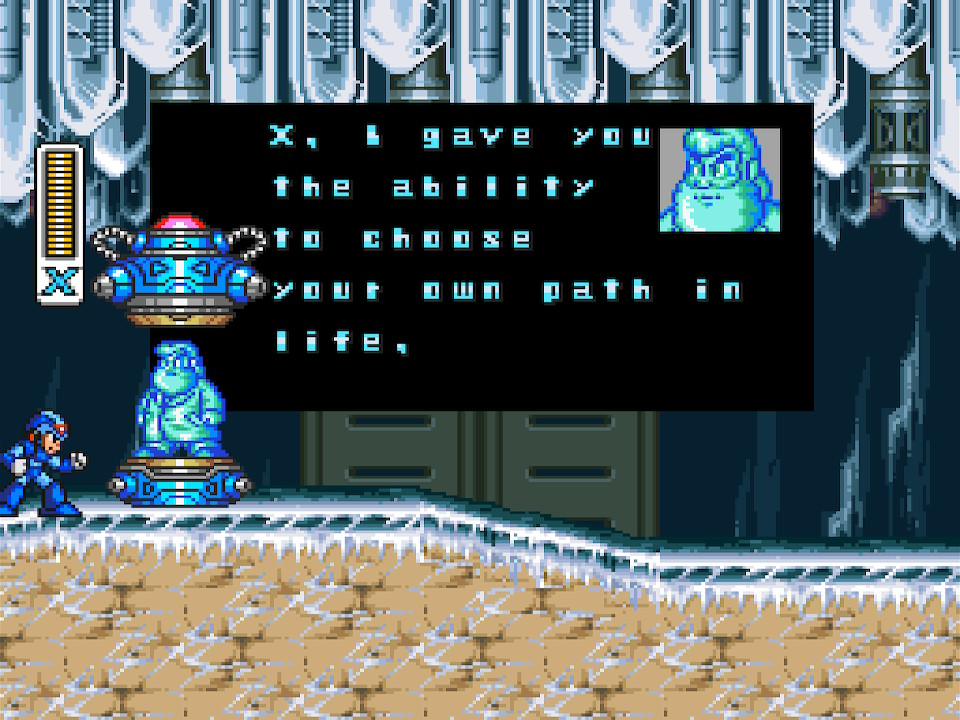

Sure enough, when you find these capsules, a holographic recording of Dr. Light shows up to welcome you and install your upgrade. Dr. Light’s recording also indicates that he’d hoped X wouldn’t need to have his offensive capabilities upgraded at all; he wanted X to awaken in a world of peace rather than one of conflict. That’s all fair and fine.

As the series progresses, however, X keeps finding capsules. He has to, because each game needs a set of upgrades to keep the feeling of gradual empowerment alive. But the Dr. Light holograms stop delivering vague “I’m sorry I died so long before you were born but I hope this helps,” messages and start commenting on the present-day state of the world, referring to things that happened and characters who were created after he died. He is also aware in later games that the world is actively at war, and is no longer optimistic that X might be living in an era of peace.

So is the Dr. Light hologram some kind of A.I. that learns and develops new upgrades based on what X needs at any given time? Or is he, as Mega Man X suggests, just some old man who did his best to plan for the future? He can’t be both.

Again, that’s not the fault of this game, but it gets pretty silly later on, when Dr. Light goes from saying “I sure wish I could have lived long enough to meet you,” to “I know what you’re going through and I’ve got a gift for you.” Personally, I think Capcom at some point just forgot the guy was meant to be dead as opposed to hiding away in a bunker somewhere but, again, we’ll get to that later.

Also, Dr. Light picked some weird places to hide his capsules. You find them here in a forest, a factory, an ice cave, and a military airfield. Nothing totally impossible to accept, but in the very next game he somehow installed one in a moving tank shaped like that stage’s boss…around 100 years before that boss was ever created. In Mega Man X4 he’ll have miraculously managed to install one in cyberspace as well. In Mega Man X5 he’ll have somehow managed to install one in a sunken Spanish galleon. BUT AGAIN THAT IS NOT THE FAULT OF MEGA MAN X SO I NEED TO CHILL OUT OKAY

Then there’s the question of whether these capsules are meant to serve as hidden rewards for thorough explorers, or natural and fundamental elements of X’s growth as a character and a fighter. Either is fine, but they’d require different executions, and I don’t think Capcom ever really made a decision.

More specifically, I think that they indeed intended for them to serve as important milestones of growth for X, but I’d argue that two of them are hidden too well for most people to find, one of them particularly so. Because of that, they can be too easily overlooked, and people will complete the game without realizing that they’d missed out on part of X’s personal journey of growth…which is the core theme of the game.

You can reward players who seek hidden items, certainly, but eight heart tanks and four subtanks already do that. The Dr. Light capsule upgrades should be uniformly easier to find, even if they’re difficult to access. That’s in fact the approach that the later games often took; the capsule would be in plain sight, but you’d need to figure out how to reach it, and I think that that’s the right way to go about things.

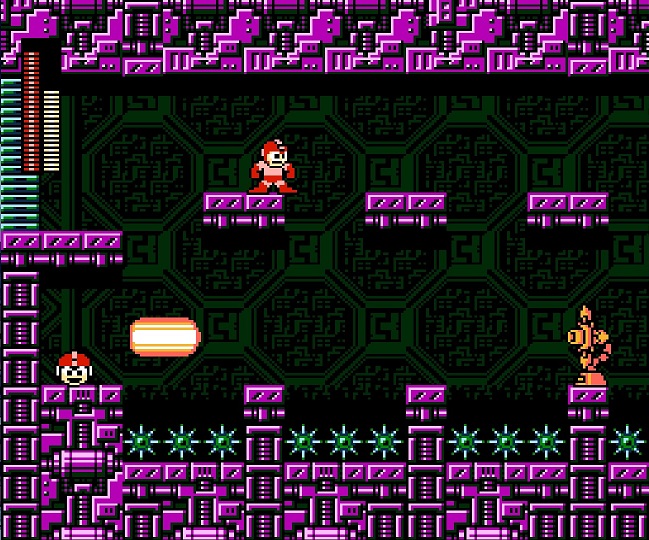

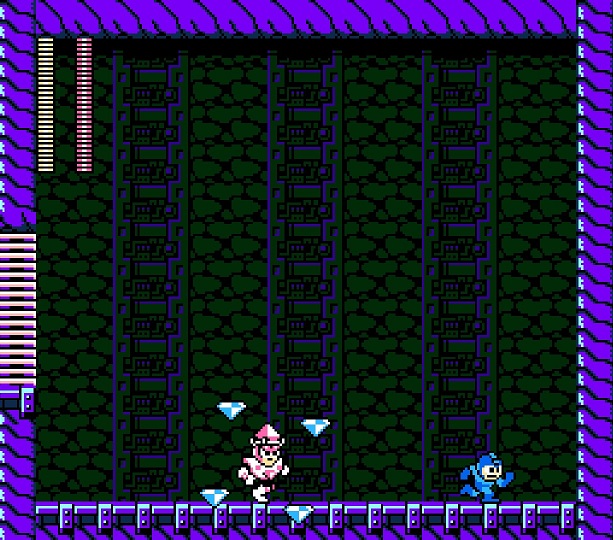

In Chill Penguin’s stage, the capsule is impossible to miss; it is in a corridor through which you must pass on your way to the boss. You can’t go around it, either; you have to activate it and receive the upgrade, essentially ensuring that you will learn how this system works. It’s a freebie, and that’s fine.

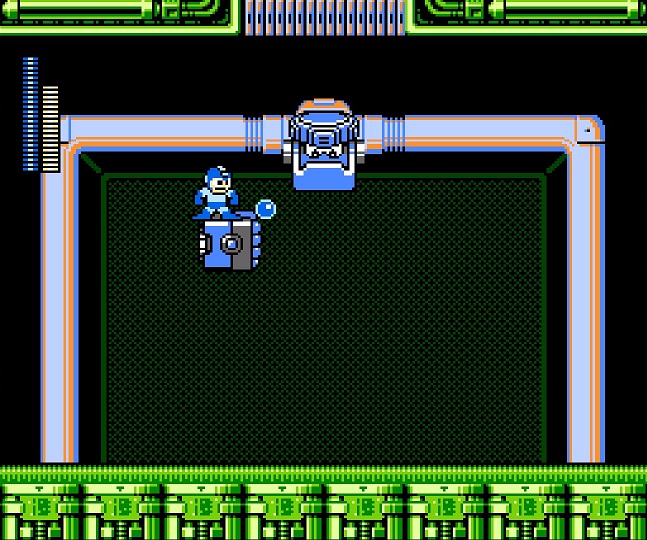

In Sting Chameleon’s stage, you need to climb a wall that leads to a new area. That’s a fair thing to expect of players in a game in which they will have already learned that they can climb walls. Once you’ve done that, you’ll face a miniboss. The capsule isn’t visible until you win the fight, but players will intuitively understand that a hidden miniboss is guarding something, so there’s enough of a chain of logic here to lead players to the upgrade. Also fine.

Storm Eagle’s capsule is debatable, but I’ll come down on the side of saying that it’s just slightly unfair. If you pay attention to your surroundings, you can notice that an ominous downward passage doesn’t lead to death, but to other platforms. That itself means that you can safely hop down there and snoop around. That much is fine, but accessing the capsule requires you to get past a series of upright canisters.

They look destructible, and they are, but they take a lot of hits before they explode. First-time players will probably see them, try to blow them up, and give up, assuming that they don’t have the right weapon to destroy them. If the canisters didn’t take so much damage before they explode, that would be fine. If the canisters displayed gradual damage, establishing that your shots were working, that would also be fine. Instead, I think the game is incorrectly teaching players to come back later…which is something they don’t have to do and may forget to do.

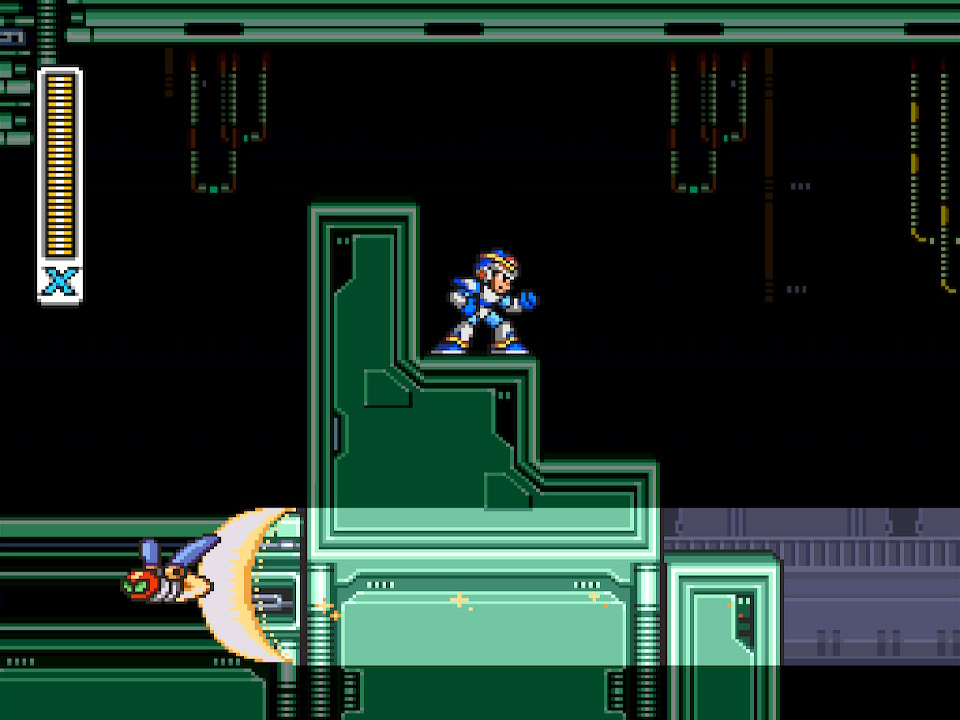

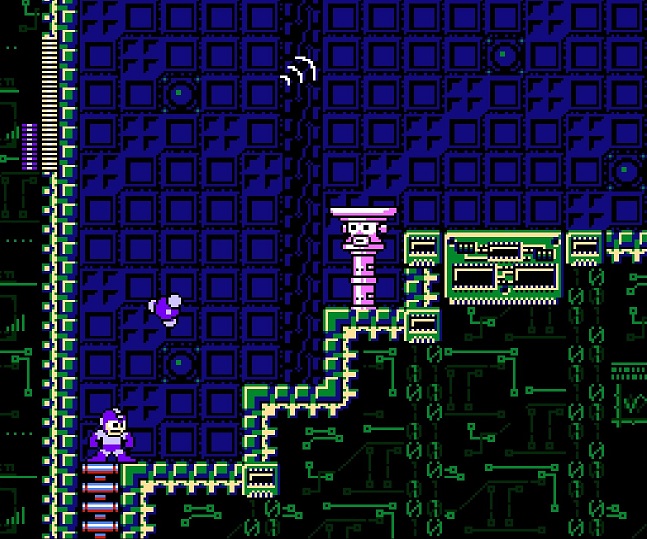

Then there’s Flame Mammoth’s capsule, which is unforgivable.

It relies on players noticing that a few grey blocks look different from the other grey blocks in the stage, and they’re placed overhead, which is not a direction the game ever teaches players to look, outside of vertical passages.

If you do notice that the blocks are different, you may try to destroy them with a weapon, but no weapon has an effect, so you may well give up and move on without realizing that you missed anything.

If you somehow notice them and understand that you need to do something other than destroy them with a weapon, you’d still have to make the wild guess that you need to physically touch them. Try doing that, though, and you’ll find them very difficult to reach. It’s doable, but as first-time players are still getting used to the controls and movement quirks, they may not spend the time necessary to learn exactly how to dash and leap from the platform on the right in order to just barely reach the blocks. Most likely they’ll try a few times, conclude that it can’t be done, and move on…and that’s if they made it this far in their chain of reasoning to begin with.

Then, if they do manage to intuit all of that, they will also need the helmet upgrade from the capsule in Storm Eagle’s stage, otherwise they won’t be able to break the blocks. If they don’t have that, they may conclude again that — even though they’ve noticed and figured out how to reach the blocks — the blocks can’t be broken.

Then, if they figure all of that out and have the helmet upgrade, they’ll have to make sure they jump perfectly enough to break the blocks in such a way that they can keep wall jumping up into the vertical passage to find the capsule. If they only break a block or two, they won’t be able to reach the vertical passage again unless they exit the stage and return, respawning the blocks and giving themselves another chance.

That’s absolutely appalling design. For some kind of very valuable (and very optional) upgrade or goody, it’s perfectly fine to hide something in an area that will be easy to overlook or difficult to access. For something essential to the character’s central journey — as I have to imagine these were intended to be — that doesn’t work at all.

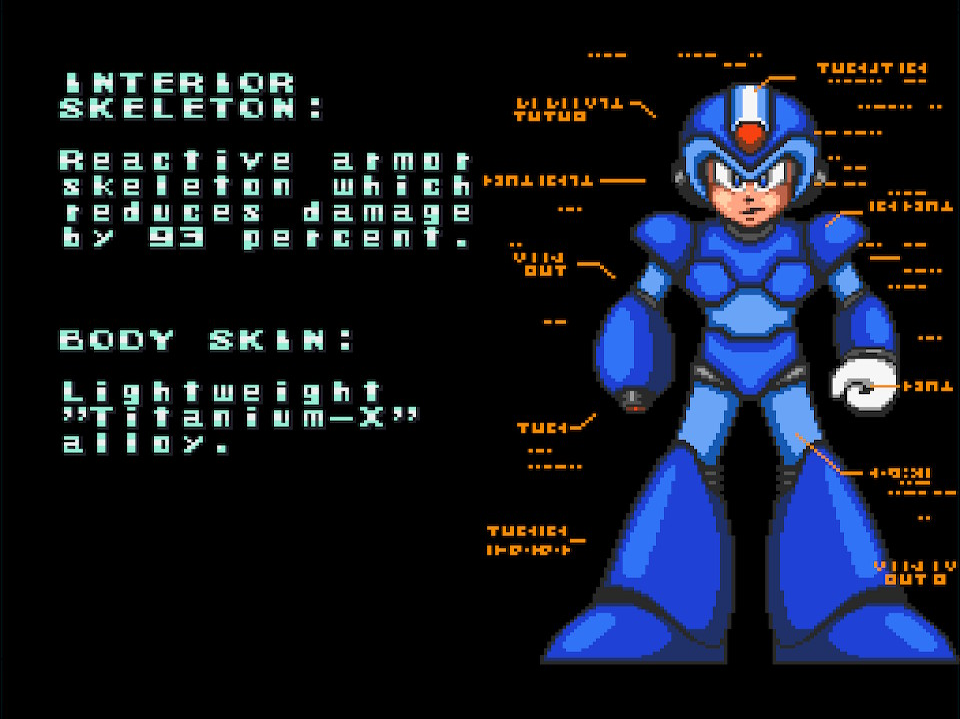

Another problem introduced by the capsules is something that we can’t really discuss until we go over what the upgrades are, so…let’s do that.

Storm Eagle’s capsule upgrades your helmet, allowing you to break blocks. This is almost never used outside of accessing Flame Mammoth’s capsule, and even worse is the fact that the demonstration of this ability is performed on blocks that look nothing like the blocks you’re meant to break in Flame Mammoth’s stage. The series would never quite figure out how to make helmet upgrades worth getting but, hey, you’ve got to start somewhere.

Flame Mammoth’s capsule upgrades your X-Buster, letting you charge your shots to even greater effect and charge your special weapons, giving each of them a secondary function.

Sting Chameleon’s capsule upgrades your body, significantly reducing the amount of damage you take. In conjunction with your ever-lengthening life bar, this upgrade is a huge help when it comes to surviving difficult stages and bosses. It’s definitely one of the least flashy upgrades — it doesn’t actually let you do anything new, so it’s hard to “feel” the difference — but it’s very welcome.

Then there’s Chill Penguin’s capsule, which upgrades your boots and gives you the dash ability. This is the only ability with its own dedicated button, and because the capsule is unmissable, the dash becomes an essential part of the experience of the game. All of that is fine, and the ability to dash is beyond handy; it feels closer to necessary.

X is slow and serves as a large target. Sure, you can learn to outmaneuver any number of enemies and obstacles, but it would be so much easier if you could move quickly out of the way, wouldn’t it? Anyone coming to this series off the back of Mega Man — who had the slide as an option for immediate dodging — would have been used to having something like this. The dash feels so essential to the game that every sequel would include it from the start, seemingly acknowledging that it shouldn’t even be an upgrade; it should just be part of who X is and what he can do.

There’s a secret capsule in Armored Armadillo’s stage, which requires players to follow a completely unintuitive set of steps to access, but it’s also very clearly an optional Easter egg, as it gives X an ability from Capcom’s Street Fighter series. It’s a joke inclusion, basically. A handy one, sure, but not part of the intended experience.

Why does all of this matter? Because, of these upgrades, the most important and significant one is also the easiest one to find. It’s so easy to find that you can’t not find it. And once you do find it, you’ll visit Chill Penguin’s stage first on each subsequent playthrough, just so you’ll have the dash available for more of the game.

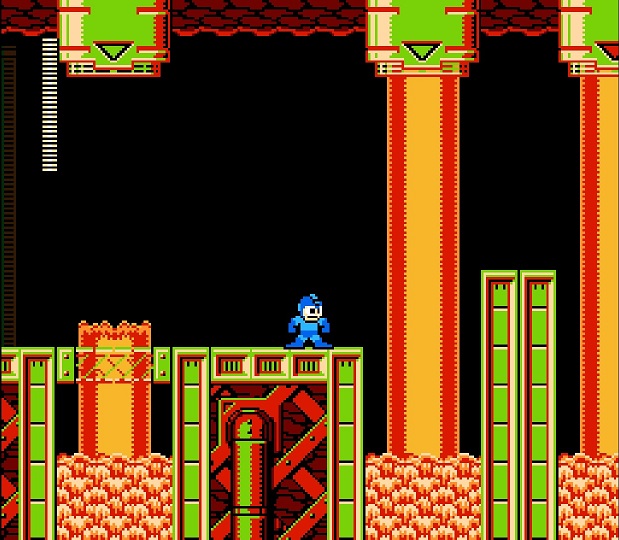

The problem? That comes when you take into account Mega Man X‘s other great innovation: environmental changes to stages, based on which ones you’ve completed.

We’ll finish that thought, I promise; but first, let’s talk about why that’s a good idea on paper.

Mega Man had essentially one way to empower himself: Defeating bosses and copying their weapons. X is able to do that in addition to upgrading his parts, finding subtanks, extending his life bar, and completing stages, which changes the way other stages play out and makes them either more or less difficult depending upon the effect.

I like that a lot. That allows for more options when it comes to progressing in the game, as you have numerous ways of making a stage easier to complete, and those options don’t always rely on which weapon you are able to bring to a fight.

The moment I provide actual examples, however, we’ll learn the problem.

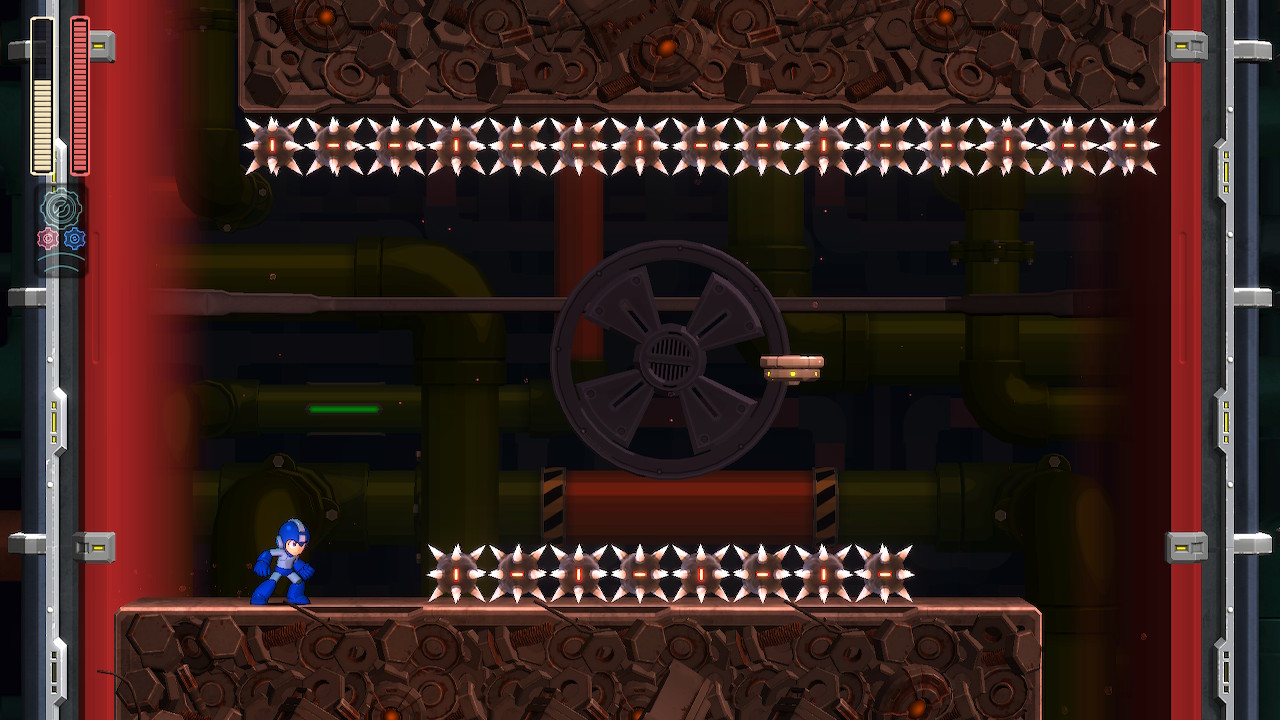

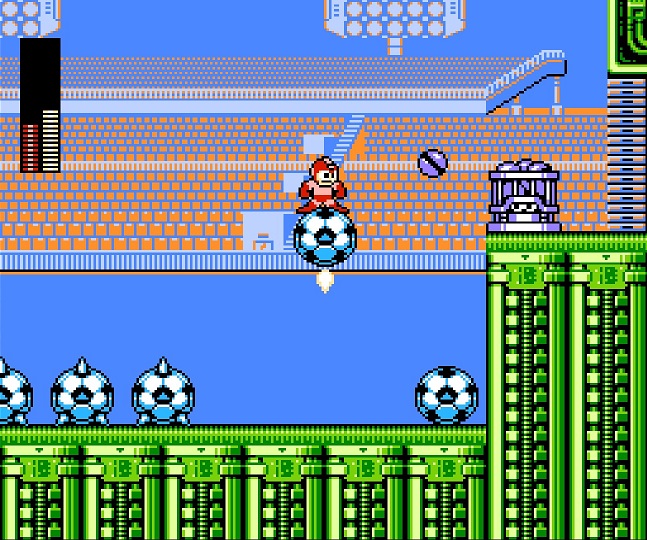

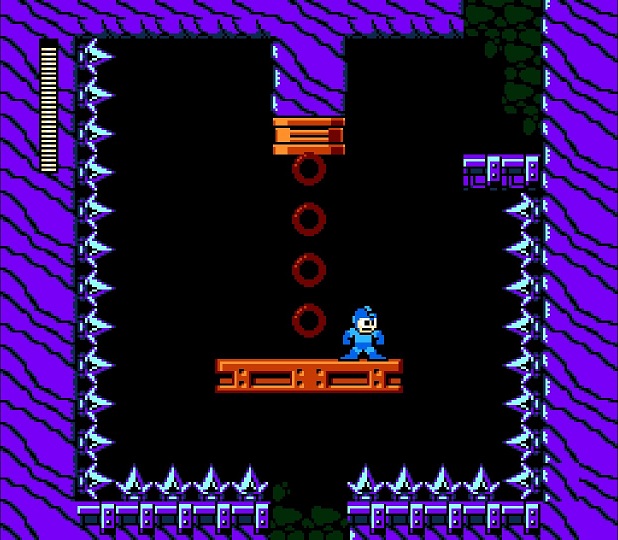

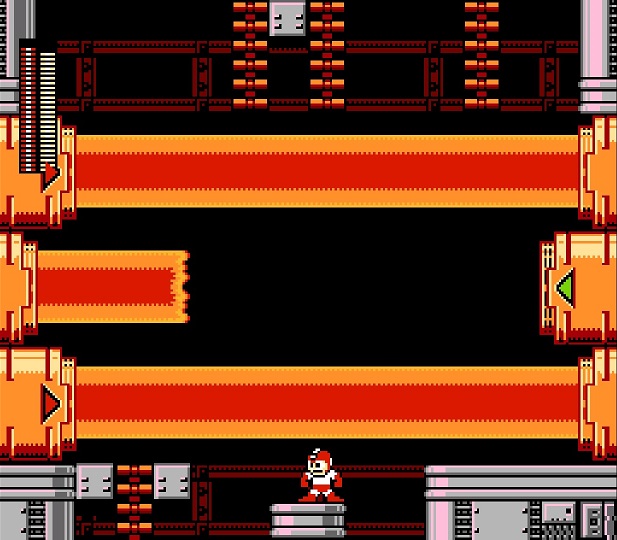

Flame Mammoth’s stage is…well…fiery. It’s full of molten lava, making the stage difficult to traverse, rendering one of the upgrades impossible to reach and making the floor in a few rooms deadly. Sounds pretty dangerous, no? Well, it is, but one of the environmental changes in Mega Man X is that if you complete Chill Penguin’s stage, Flame Mammoth’s stage ices over.

Why? No idea, but it does. Now the floor won’t kill you, you can easily grab the heart tank, the stage overall becomes much less treacherous, and so on. The issue is now apparent; since you’ll want the dash, you’ll beat Chill Penguin first. Once you do that, you’ll never even see the “proper” version of Flame Mammoth’s stage; you’ll only ever play through the less-challenging version.

Of course, you could decide to not fight Chill Penguin until later. Or you could visit Chill Penguin’s stage, grab the upgrade, then kill yourself enough times that you can exit the stage and try another one. At that point, though, you as a player are trying to find ways around Capcom’s own flawed design. You’re trying to fix the game for them, and for no real purpose. Their own design works against players experiencing the game in full.

The house of cards doesn’t stop falling there.

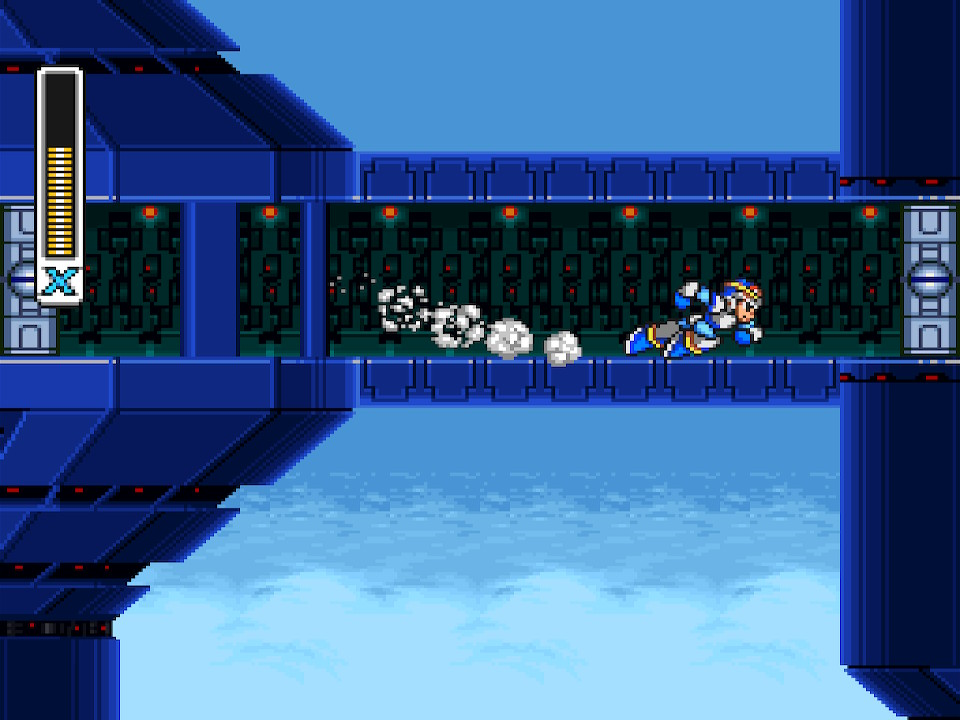

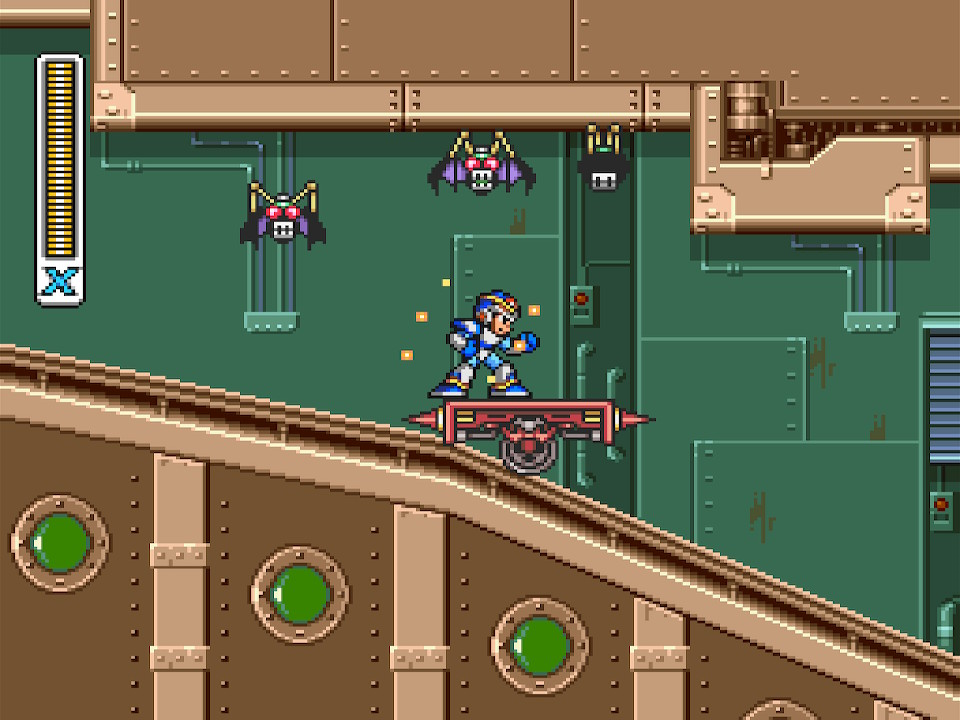

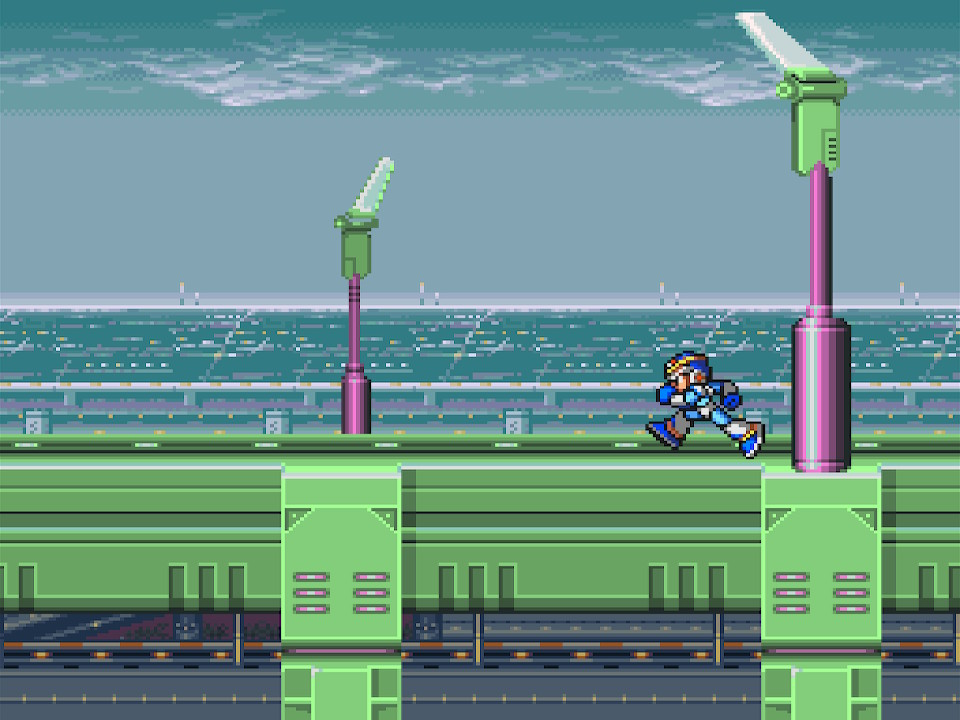

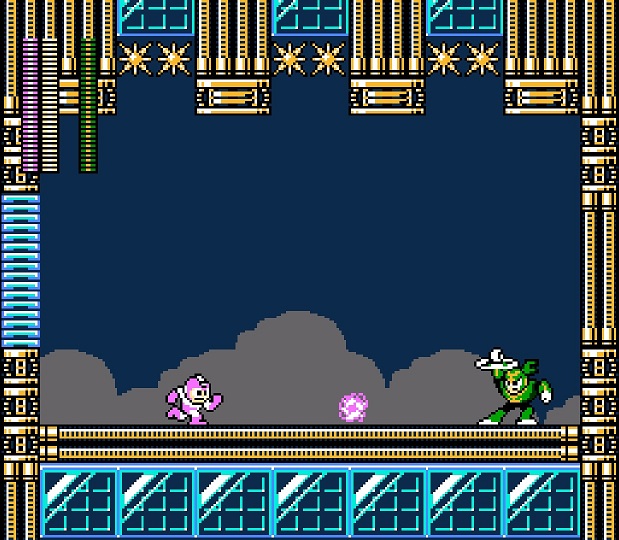

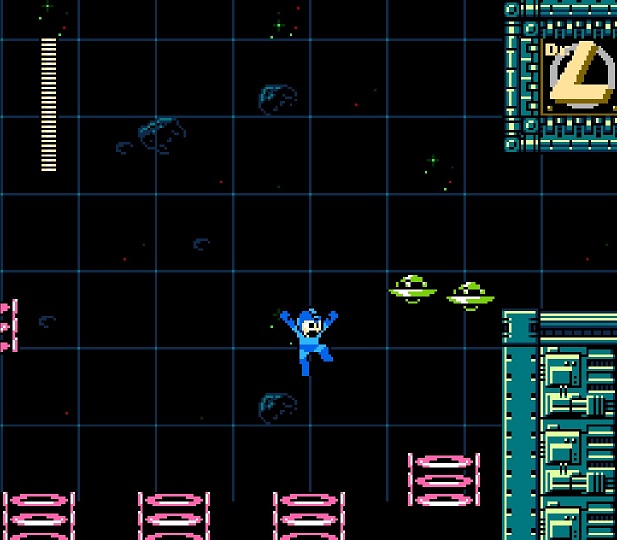

Storm Eagle’s stage will likely be one that players do soon after Chill Penguin, as his wind attacks push you backward. They don’t hurt you, but they can easily blow you into a pit. Once you get the dash, you’ll intuitively understand that you can use it to keep him from blowing you into the abyss, and you’ll be right. Now his attacks aren’t dangerous at all and you’ll defeat him easily.

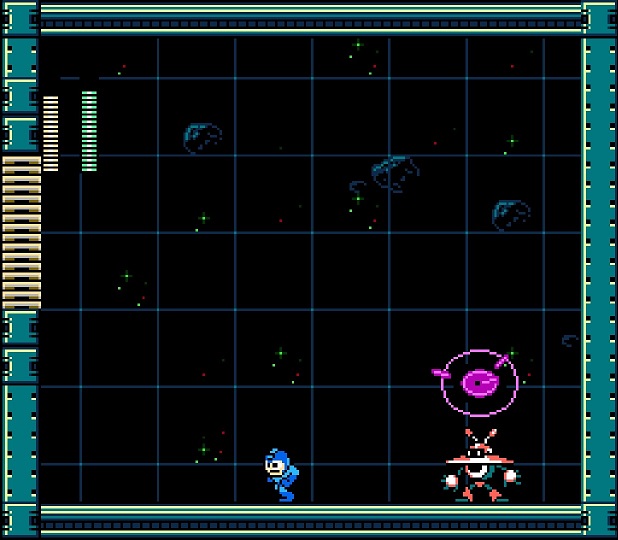

Do that, and his aircraft crashes into Spark Mandrill’s stage (I think; again, the game isn’t clear about why finishing one stage affects another), turning off the power. This removes a number of electrical traps from the stage and robs the miniboss of its most powerful attack. Once again, just by progressing logically through the stages, you’ve robbed this entire level of its danger.

Granted, the lack of power means that a few rooms are darker than they otherwise would be, but it’s never difficult to see where you’re going. I believe that the intention was to change the specific kind of difficulty you’d face in the stage; instead of dodging powerful traps and attacks, you’d have to learn to advance through darkened areas. Nice idea. In practice, however, the latter isn’t even slightly challenging, as you can still see the platforms just fine.

The only other environmental change that I noticed is that defeating Launch Octopus floods one of the lower areas of Sting Chameleon’s stage. I’m sure that that makes perfect sense to somebody, somewhere, but I’m at a loss to explain it.

That’s it, and it’s easy to see how Capcom could have fixed this. They could have made more stages alter each other in this way, so that even though a few stages get easier, others would become more challenging, balancing things out. Or they could have had some of the effects work differently. For instance, what if defeating Chill Penguin meant that Flame Mammoth’s stage got much more difficult instead of easier? Then there might be an actual reason to delay getting the boots upgrade. Or, of course, you could just put the boots in a completely different stage that didn’t affect how others played out.

Really, they could have done anything to improve this, so it’s a huge disappointment that they basically scrapped the concept of environmental interactions after this game. I know there’s at least one in Mega Man X3, but it doesn’t really come back into any kind of actual focus until Mega Man X6, where I’m sure it works wonderfully and will make everybody happy.

It’s disappointing that Capcom hit upon such an interesting idea with these different versions of the same stages, and then abandoned it without refining it. I’m not going to complain too much — I like a lot of things about the way in which the series evolved from here — but that is a very disappointing missed opportunity.

Then again, maybe that’s for the best. With Mega Man, Capcom only had to dream up eight new bosses and weapons for each game, in terms of anything that would really affect the gameplay. In this series, each game would require eight new bosses, eight new weapons, at least four new capsule upgrades for X, and — based on what we saw here — new ways for the levels to interact. That was probably too tall an order for every sequel, and they sacrificed the right thing.

I’m just disappointed that the concept was only really used here, and also happened to be executed so poorly that we never got to experience its full potential.

As far as the stages themselves go, they’re pretty decent. I wouldn’t rank many of them as standouts, but I also wouldn’t say that any of them are bad, or even close to it. By this point, Capcom had spent five games learning how to design a great Mega Man stage on the NES, and though Mega Man X has a different enough approach, it’s not so different that Capcom is left starting from scratch. The lessons learned there serve them well here.

For whatever reason, I end up comparing it in my mind to the way the first stretch of Simpsons episodes can be really rough with glimmers of greatness, but when Futurama started, it was hitting greatness from the start. They were very different shows, but the team learned enough from working on one that they could benefit from those lessons when starting the other. Mega Man X is definitely a Futurama situation in that regard, as it starts off on firmer ground than the previous series did, and that’s a win for us as much as it is for Capcom.

In fact, years ago, after I taught myself to complete each Mega Man stage without taking damage, I tried my hand at Mega Man X. To my surprise, it wasn’t only doable; I found it comparatively easy. Was that because I was great? Well, no; it was because there weren’t as many design quirks that I needed to work around and account for. Capcom had level design nearly down to a science at this point; I’d rarely get caught unaware as long as I paid attention. Mega Man X isn’t easy, but it’s certainly fair, and that made a big difference.

The only stage that took me more than three or four attempts was Launch Octopus’, and that was mainly due to the Maverick himself, whose attacks need to be handled with good reflexes. Even then, it didn’t take me very long to complete the stage without getting hit; it just took slightly longer. I’m sure the later games would have been harder, but I don’t think I attempted those. Perhaps one day.

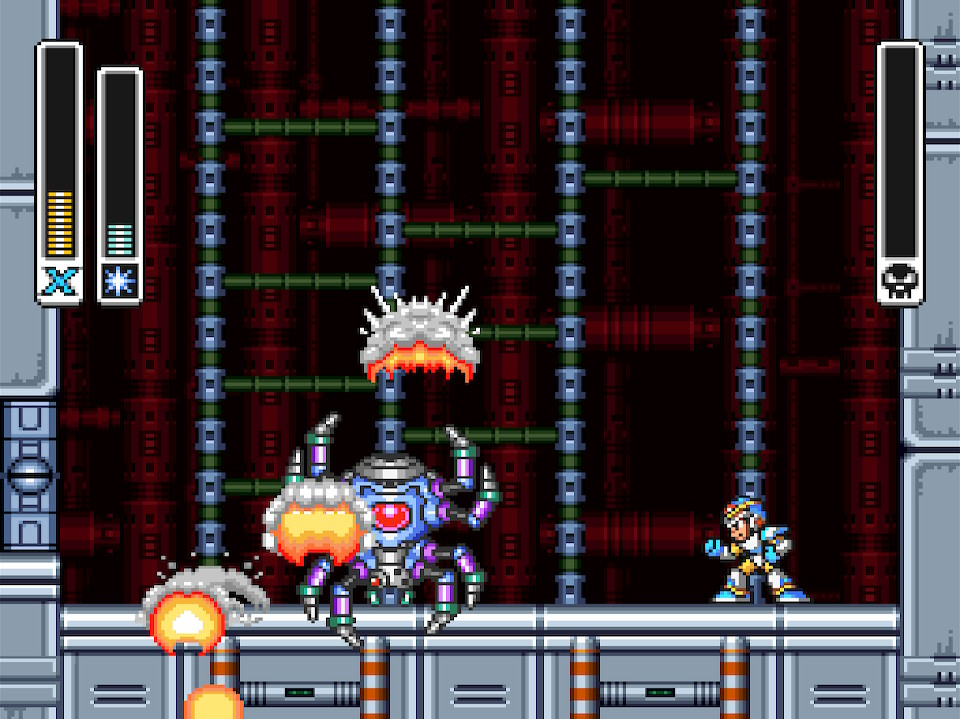

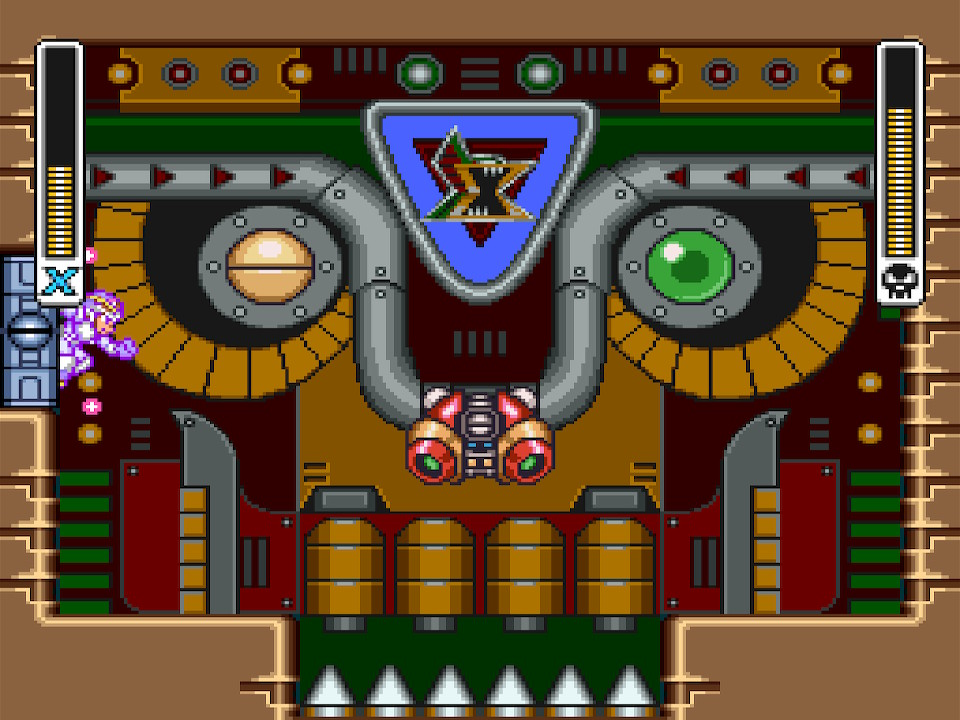

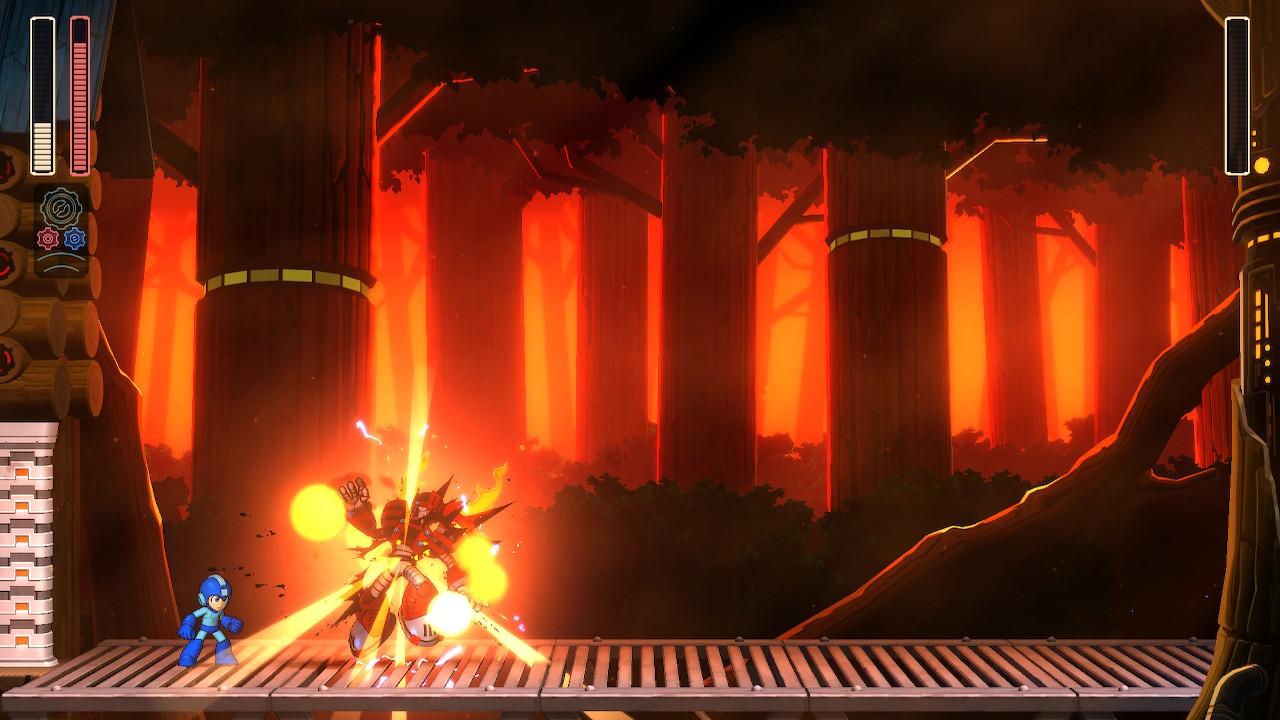

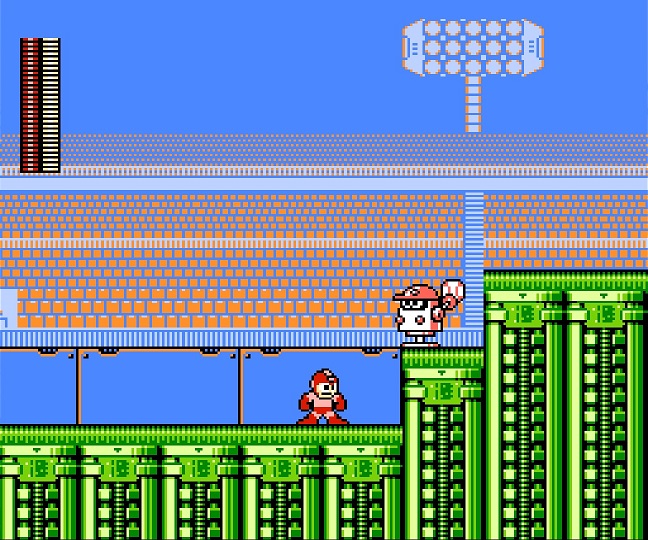

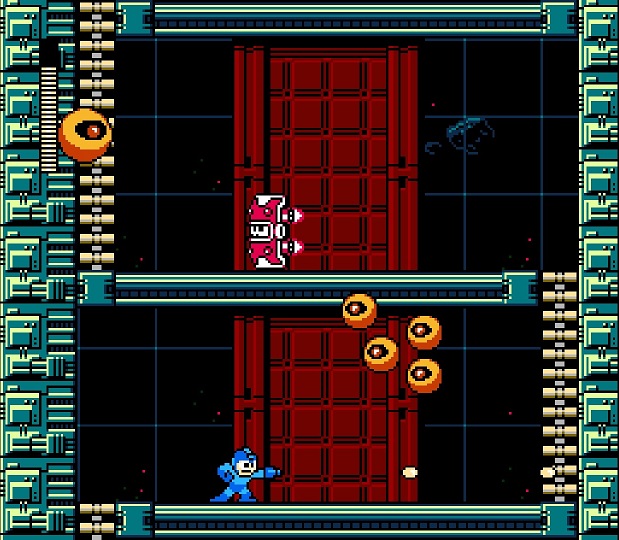

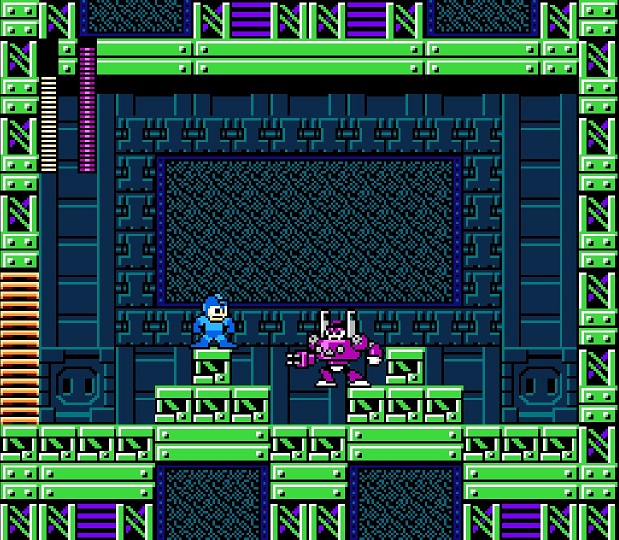

The Maverick fights don’t do much that’s unfamiliar to Mega Man veterans. Flame Mammoth and Spark Mandrill are much larger than any standard bosses on the NES, which doesn’t make them more difficult but it’s nice to see Capcom embracing what they could do with the new hardware.

Flame Mammoth’s fight also takes place in a wider boss room than usual, and Storm Eagle’s fight doesn’t take place in a room at all, but rather on top of an airship. Fights like that stand out in ways that I really enjoy, as it demonstrates a willingness to experiment. Does a longer boss room really matter for Flame Mammoth? Nope, but you never know until you try, and I love that Capcom did more than just give us animal-themed bosses this time and call it a day.

They were trying to tweak everything to some degree. The movement. The weapons. The exploration. The bosses. Everything got some kind of attention that, strictly speaking, wasn’t necessary. Not all of it worked perfectly, of course, but this was a new series. It was the beginning rather than the end. Mega Man X wasn’t flawless, but it was loaded with potential, and that’s what mattered. (And it was also pretty darned great, to be honest.)

All of this does an excellent job of giving Mega Man X a very different personality to the main Mega Man games. Superficially, they have a lot in common. (Too much, I’d argue.) Fundamentally, though, the experience is completely different and feels unique. So much so that anyone who attempts to play this like a Mega Man game — without learning how to take advantage of what makes X different — will find themselves failing, stopped dead multiple times, and frustrated at just about every junction. And that’s exactly how it should be.

Mega Man X takes the Mega Man foundation and builds something completely different on top of it. It’s familiar enough that we will already understand much of what we need to know, but the learning of new details, wrinkles, quirks, and abilities starts quick, and it continues throughout the entire game. It’s impressively designed.

Was there anything I didn’t like? Well, yeah, of course, I’m still me.

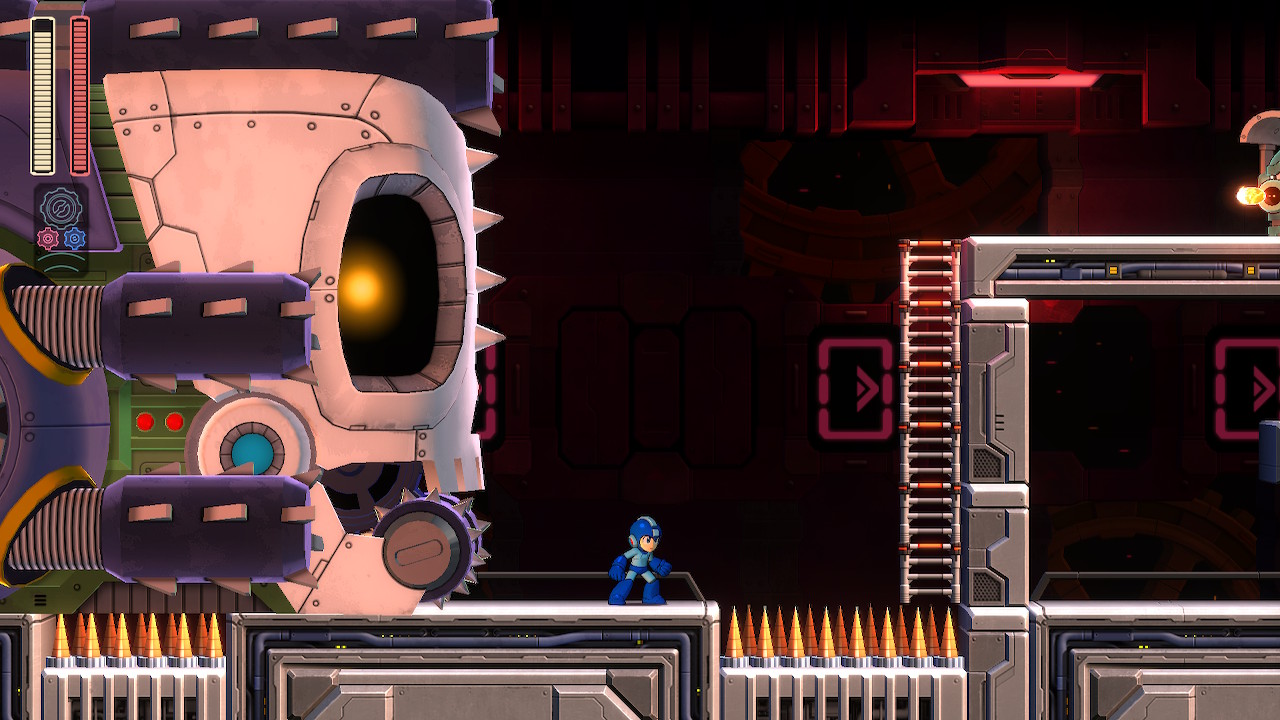

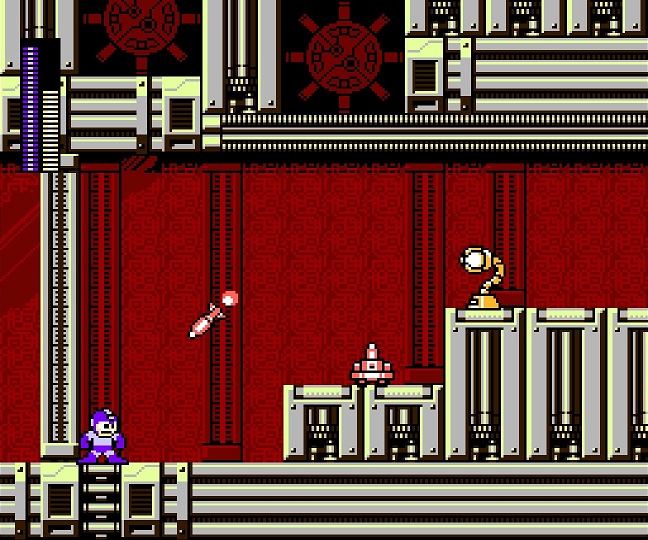

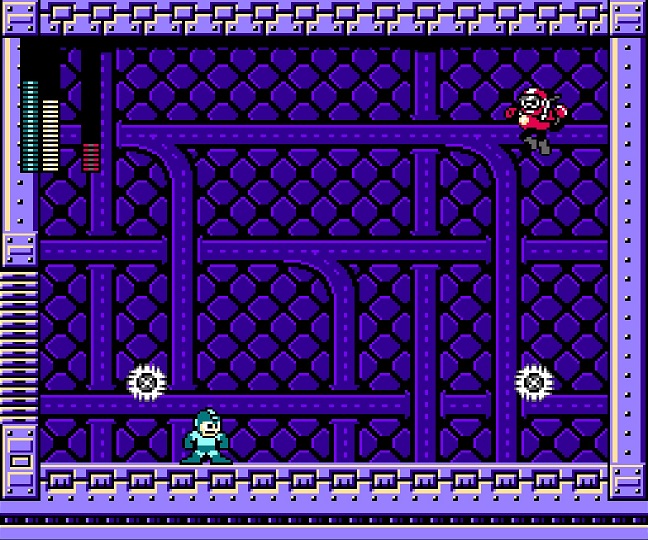

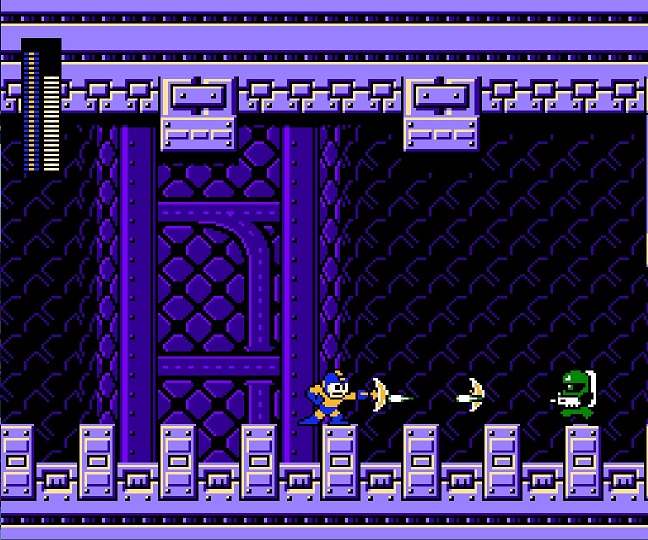

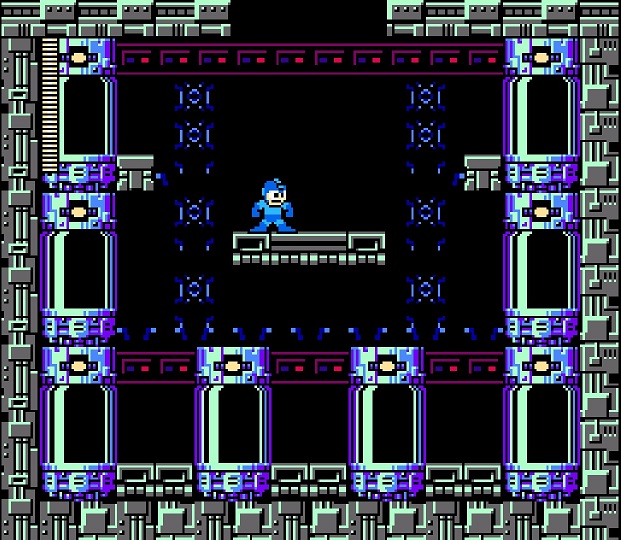

The Sigma stages sadly follow in the tradition of the Wily stages as being…pretty crap. If I remember correctly, some of the later ones are much better, but the ones in this game are just long and difficult without much real personality. Particularly annoying are the vertical climbs — sometimes without a safe place to land — while durable enemies shower you with attacks.

There are easy ways through this — charging up either the Rolling Shield or the Chameleon Sting will render you invulnerable — but I don’t like that there’s not a fairer way to get through these sequences. You can either take a lot of time picking off enemies and making slow progress, or you can use a weapon that makes you invincible and barrel through it without any thought at all. I tend to feel more engaged when I can proceed in some way between those two extremes, but that’s not a huge deal.

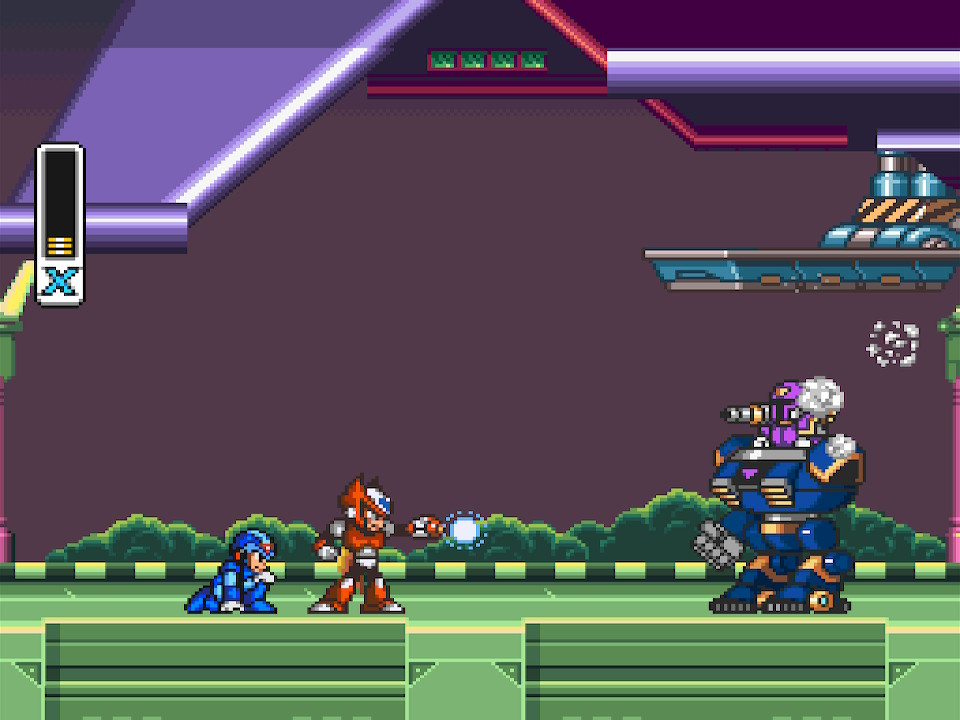

At one early point in the Sigma stages, you square off against Vile again. This should be a great time to feel how much you’ve grown. You’d get to go from getting your butt kicked in the intro stage to holding your own in a fight against him, and that would be great. Instead, for whatever reason, the game still requires Zero to show up and save you. You do get to fight and defeat Vile, but not without Zero sacrificing himself to weaken Vile first, which dulls the feeling of personal growth somewhat.

Also, Zero is a great character, as we’ll see, but he doesn’t do all that much in Mega Man X. He makes the theme of the game explicit in the intro stage, telling you that you need to get stronger if you’re going to defeat Sigma, and then he shows up here to help you on your way. That’s about it.

None of that is a problem, but considering how important the relationship between X and Zero becomes to the series — and to Zero’s own series — it’s a little strange to see him make only brief appearances here. That’s another “problem” that only exists in retrospect, I admit, but it’s worth bringing up.

Interestingly, if you didn’t pick up the X-Buster upgrade from Flame Mammoth’s stage, Zero gives you his own buster at this point. It behaves exactly like the powered-up X-Buster, but this is the first example of the narrative playing out differently depending upon decisions you make throughout the game. That will become a major aspect of this series — not always in a good way — so it’s worth spotlighting here, as one singular, early instance of Capcom testing out the idea.

…which leads to another bit of retroactive strangeness, as Zero’s main weapon would soon be established as the Z-Saber, which isn’t even seen in this game.

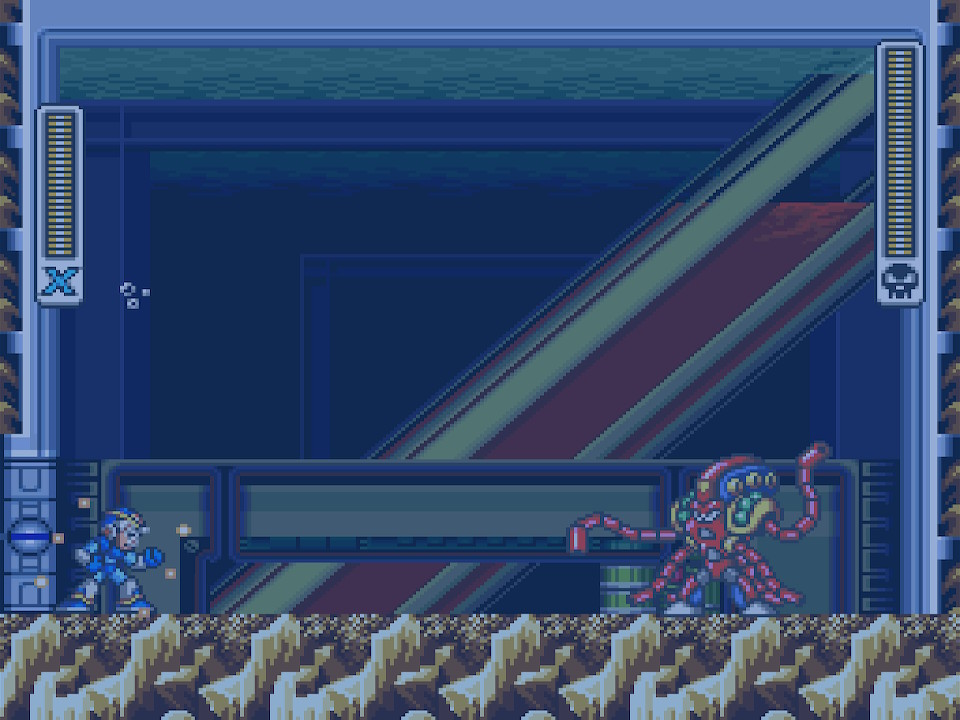

Hmm…what else? Well, the bosses are a bit too easily demolished by their weaknesses. You can choose to not use their weaknesses, of course, but it would be nice if their weaknesses just made them easier rather than turned them into outright pushovers. Launch Octopus at least holds his own against his weakness, so that’s something.

In a similar vein, there’s an interesting aspect of the Boomerang Cutter. If you use it against Flame Mammoth or Launch Octopus — neither of whom are weak to it — you can shear off bits of their bodies, preventing them from using certain attacks. That is an interesting idea, and it’s similar to the way in which the Thunder Bolt in Mega Man 7 has special interactions with Spring Man and Turbo Man.

Like the special interactions in that game, though, this feels like the developers got partway into implementing a larger idea and gave up. It’s strange that only one weapon triggers boss responses along those lines, and it only happens with two bosses. (The Electric Spark causes Armored Armadillo’s armor to fall off, rending him more vulnerable to other attacks, but that weapon is his weakness so I don’t think it’s worth counting. Nice touch, though.)

Also, there are a pair of sound effects associated with the subtanks. When you add health to a subtank, you hear a quick series of sounds that brings to mind a stack or a pile of something getting slightly larger. When you completely fill that subtank, you instead hear a nice, twinkly sound that suggests a feeling of completion. In the later games, if memory serves, those sounds are reversed, running counter to the mental associations each sound conjures so easily. Again, that’s not the fault of this game, but if I don’t mention it here, I’ll forget to mention it later, so you have to live with it.

The music is also not quite what I would have hoped for. Most of it is pretty forgettable, and while I appreciate Capcom’s attempts to take things in a more atmospheric direction, I just don’t think it works. I do think it works better in the later games, but the compositions here tend to just…be there. I realize that I am in the minority on that but, hey, I’ve got to be honest.

I do really like the Storm Eagle track, which is indeed perfect for a 16-bit hero smashing his way through an airforce base and then taking to the sky. Spark Mandrill’s is also nice and energetic, if not especially memorable. My favorite, though, by far, is Armored Armadillo’s frantic, energetic, barrelling tune that perfectly fits the underground chaos of his stage.

That’s also the only ground-based stage I think I’ve truly loved in any of these games. It’s far too quick and easy — you ride on little carts through most of it and just fire your weapon so you don’t collide with enemies — but it’s fun, and it’s a nice breather. Also, again, great music, meaning that I save it for last every time, as my little reward for being good.

That’s about it as far as complaints go, and those are really all varying shades of “minor.” Mega Man X was and remains a profoundly confident step in a new direction, and though I could pick it apart for whatever flaws I think it has, it’s far easier to celebrate just how good it is.

It looks great. It feels great. It’s full of great ideas, many of which are executed well and even more of which will be executed well in its sequels. It’s a remarkable achievement, and though I didn’t truly give the game the attention it was due until I was an adult, that’s entirely down to me and the fact that I didn’t engage with it long enough as a child to realize how much it had to offer.

In a very large way, that was my loss.

In another way, it meant that I could discover as an adult, for the first time, a whole set of brilliant retro games that I’d never gotten to properly experience before. That’s a kind of magic in itself.

…okay. Maybe not a whole set.

Best Maverick: Launch Octopus

Best Japanese Maverick Name: Burnin’ Noumander

Best Stage: Storm Eagle

Best Weapon: Boomerang Cutter

Best Theme: Armored Armadillo

Overall Ranking: X (Once again, this will make sense later.)