There’s a reason that most sitcoms either rarely attempt emotional episodes, or make sure to undercut them when they do. To put it flatly, emotion is a tricky beast. Shows that traffic in it (see just about any daytime drama) become easy punchlines, and shows that don’t run the risk of annoying or alienating their fans when they make an attempt at seriousness.

Comedies are problematic when it comes to emotional content. People tune in to them not only because they like to laugh, but because they like to laugh with that particular show’s characters, tone, and comic sensibilities. When you hijack an audience’s regularly scheduled sitcom to present A Very Special message about drug addiction, date rape, or divorce…and when you put that Very Special Message in the mouths of the very actors we expected to make us laugh…it feels like a kind of betrayal. The messages and emotion are almost necessarily ham-fisted, because they so clearly don’t belong in a multi-camera sitcom with a live studio audience, a peppy theme song, and a wacky neighbor.

That’s not to say “serious” episodes can’t work, but it is to say that there’s no definite recipe for success, and thousands of examples of quite varied failure.

Some comedies decided to weave emotion into their stories from the start. In the case of M*A*S*H, for instance, dramatic moments actually suited the context of the show rather than distracted from it; it took place in a hospital camp during wartime, after all. We didn’t need, necessarily, to see the darker side of war, but when it reared its head it was impossible to dismiss as being out of place.

Another emotionally successful comedy is Futurama, and it’s no coincidence that that show’s most memorably devastating moments came at the end of an episode, rather than at the beginning or during. Seymour waiting, the destruction of Fry’s cosmic confession to Leela, the flashback of Hermes saving a defective Bender from the scrapheap…all of these things happen at the end of an episode. Until the curtain falls, you are watching a standard half-hour of the show. As a result, the emotion punctuates the story, rather than overpowers it.

But those are successful exceptions. Most of the time sitcoms swap out their standard approaches for something entirely different. And, most of the time, it’s a fucking disaster.

ALF takes an enormous gamble with “Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow.” (As with the Gilligan’s Island episode, I’ve had to truncate the title for the WordPress headline.) It unapologetically goes the ham-fisted route. You may have tuned in expecting off-the-wall alien hijinx, but instead you’re getting a straight-faced examination of a minor character’s strained relationship with his mother.

The fact that it works is a miracle. Of all the sitcoms that have attempted drama over the years, ALF would be the last one I’d expect to be successful. And yet here we are.

I’m every bit as shocked as you.

We’ll get to why it works later on. For now, we’ll focus on the opening sequence, which is quite good. It’s punchy, it’s funny, and it reveals the central conflict of the episode in a clever way. It’s a good start to an episode that, by and large, lives up to its promise.

“Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow” begins with the Tanners finishing dinner. Kate brings out some pie as Willie compliments her on the meatloaf. She corrects him; it was Salisbury steak. ALF says to Willie, “Great. Meatloaf with an attitude.”

I can’t decide if I actually like the line or not, but the delivery is funny enough that it saves it from just being more Kate bashing. (The deliveries of many other lines in this episode save them, thankfully, from the same fate.)

Then there’s a knock at the door and Jake’s voice, and Willie calls out “Door’s open, Jake!” in a happier tone than I think I’ve ever heard this character speak before.

You know how I’ve floated the idea that early drafts of these scripts established a kind of bond between Willie and Jake? Well, moments like this really reinforce that thought for me, especially since Willie tells Jake he’s glad to see him, because “We haven’t seen you around here for quite a while.” It turns out to have just been a few days…which wouldn’t be long enough to register with someone if they were just neighbors. Friends may visit regularly, yes. But neighbors? Nah.

Somewhere in the hatchet-happy revision process, I’m convinced that we lost scenes of Willie and Jake finding unlikely friends in each other. Two isolates in a world they don’t particularly like, two nerds in their own ways, two people in search of a family and friends that understand them. Echoes of it survive in scenes like this. I sure wish we could have seen the whole thing.

Usually in these reviews I list every line that made me laugh, but already I’m having to leave a lot out in the interest of time. (The brief discussion of Mr. Ochmonek’s dislike of dried fennel — he prefers it fresh — is such a lovely, specific, genuinely funny flourish, for example.) That’s because in most episodes, so little works that it’s easy to be comprehensive. In this episode, nearly all of it works, and I actually have to be selective. It’s…a good feeling, I admit.

Jake explains his absence by saying, dismissively, that somebody’s been staying with them lately. He doesn’t make eye contact. He doesn’t want to tell the whole story. Kate, oblivious, sees that he’s not going to continue, so she asks, “A relative?”

Jake’s reply is instinctive. He says, “Sort of.”

It’s the classic response of somebody who doesn’t want to talk, but is forced into saying something.

When he explains, “It’s my mother,” it both works as a joke and as a punch to the gut.

On its own, this moment might not have meant much. In light of what’s to come, it’s the perfect introduction to a tonally distinct episode. It’s both funny and effective emotionally…two things that never come easily to this show.

The scene continues with the family discussing that Jake’s never mentioned his mother before…and there’s a great unspoken moment when the kid has no idea how to respond and nearly walks out of the house. Willie stops him (again, suggesting a kind of bond between them) and I love the fact that we don’t end with the shock of “It’s my mother.” The show allows that moment to play in its quietly sad way, and also to function as a laugh-line in a larger, ongoing sequence.

In other words, the introduction of this episode’s emotional component doesn’t bring it to a dead halt, which, I believe, is why it succeeds. The emotion doesn’t overshadow the comedy; they coexist. “Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow” might not try as frequently to make us laugh, but it still does try. And the emotional content gives the jokes more room to breathe, making them seem funnier than they typically are.

I’m surprised at how effectively this episode played on my feelings. I’m even more surprised at how often it made me laugh.

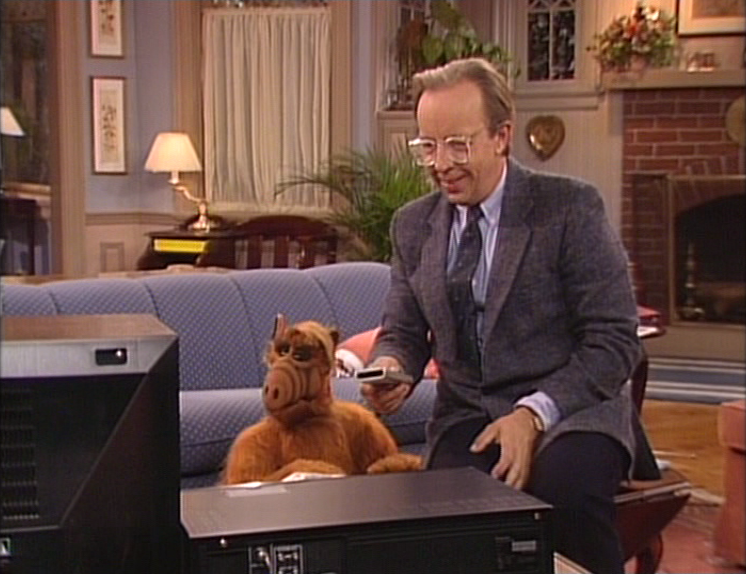

After the opening credits, Willie verbally spars with ALF and licks his lips while eyeballing the alien’s naked, rippling chest.

Once again Willie and Kate are sitting on the couch, facing different directions, reading different things, in total silence, not touching each other. For crying out loud, there was more overt affection between Al and Peg Bundy. If at any point ALF had something to say about the stagnation of this marriage, I’d look at things like this as interesting, subtle ways of reinforcing the theme. Instead it’s just two actors who can’t be bothered to pretend they know each other, let alone act like they’re in a healthy and happy marriage.

Want to know why I believe the Ochmoneks are in love while I’ll never believe the Tanners are? The Ochmoneks touch. One laughs when the other makes a joke. They do things together. They do things for each other. They have date nights. They look each other in the eye. And, as we learn here in an offhand comment from ALF, they have a sex life. How much of that applies to the Tanners? None of it that I’m aware of.

Are Willie and Kate in love? We’re told they are. But if we go only by what we see, I’d never draw that conclusion. Roommates, maybe. Spouses? Impossible.

After the opening titles we see the most surprising thing about the episode: writing credits for Paul Fusco and Lisa A. Bannick.

Fusco, as you know, is the egomaniacal supervillain that began ALF as a legal way to torment and slowly murder Max Wright. He’s also, to be fair, an impressive and genuinely talented puppeteer, but his strengths have never had anything to do with writing or characterization.

Bannick’s previous writing credits on this show include “Wedding Bell Blues,” “Prime Time,” “Hail to the Chief,” “Tonight, Tonight,” and “Baby Love,” which reads like an incomplete list of the worst ALF episodes recited from memory.

Together, somehow, they both have their names on this uncommonly strong episode, which plays to the unexpected strengths of a problematic supporting character and fleshes out his backstory. This is incredible. It’s the ALF equivalent of walking on water.

Mrs. Ochmonek comes over to introduce Jake’s mother. I’ll get to her in a bit, but, first, let’s talk about the other thing we get introduced to: this episode’s approach to the Ochmoneks.

Normally, I’m baffled. Jack LaMotta and Liz Sheridan do the best they can with their characters. LaMotta is especially funny with his limited screentime (and ALF-quality gags), but what makes them stand out is the fact that they’re actually acting. They don’t just turn up, recite their lines, and walk off the set. That describes almost everybody else’s approach to this show, but LaMotta and Sheridan at least try. And I love them for it. I love them far (far, far…) more than I love any of the Tanners, which is what’s so baffling. Aren’t I supposed to hate these guys?

The show never quite got a handle on how to make us like the family we’re supposed to like and dislike the family we’re supposed to dislike. Even if we ignore the fact that LaMotta and Sheridan are clearly better actors, the show doesn’t accurately characterize either family, at all. The Ochmoneks are regularly doing nice things for the Tanners, nearly always spur-of-the-moment, and never receiving any kind of appreciation in return. On the flipside, the Tanners are consistently rude, condescending assbags. We’re about to enter the final season, and nobody involved with the show has realized any of this yet.

But this episode does what’s only been done maybe twice before: it positions the Ochmoneks as the right kind of irritating neighbor, and it does so from the start. Here, Mrs. Ochmonek introduces Jake’s mother to the Tanners and, after letting her gaze linger too long on Kate’s belly, explains, “She’s pregnant.”

The Ochmoneks aren’t cartoon characters, and they’re not assholes. They are (or should be) people who don’t really think before they speak. They’re not bad, they’re just uncouth. A little dim. Unaware of the fact that the way they live their lives isn’t the way that everybody else lives theirs.

And that can be annoying. In fact, in reality, that is annoying, and it probably describes pretty well the kind of people you yourself avoid whenever possible.

The Tanners don’t need to sit around making fun of Mr. Ochmonek’s war injury or Mrs. Ochmonek’s saggy tits. They just need to try to be civil and find themselves up against unintentional rudeness. That’s how you convince me that I’d be annoyed by the Ochmoneks; you emphasize their lack of self-awareness. You don’t tell me they’re fat and old and assume I’ll agree with you that yeah, the world would be a better place without them, and it’s right to treat them like scum.

Anyway, it’s a promising indication of the way the rest of the episode will pan out, and that just won’t do, so Willie reminds us that we’re watching ALF by making a funny face.

Kate suggests that they should all get together while Jake’s mother is in town, and Mrs. Ochmonek immediately volunteers her to make dinner for them tomorrow night. Jake’s mother says she doesn’t have to go through any trouble on her account, but Mrs. Ochmonek says, “Oh, pish. Kate doesn’t mind. Do you, Kate?”

All of which is rude without intending to be rude, and which fences Kate into hosting a gathering that she doesn’t especially care to host. It develops the story, builds character, and sets up the next plot point without feeling forced.

See how much better this shit is when somebody thinks before writing it?

Jake’s mother thanks the Tanners for all they’ve done for Jake. I’d love to make a snarky comment here, but, yeah…they actually have been pretty nice to him. They first met the kid, remember, the day he decided to burgle their house, and he’s been relentlessly trying to fingerfuck their daughter ever since. But he’s a welcome presence in their house; Willie seems to like him, ALF hardly rapes him at all, and he knows Brian’s name. The kid’s a miracle worker.

When he was introduced in “The Boy Next Door,” he stole Willie’s telescope. Later on ALF confronted him about it and taught him that “Repairing is cool, but stealing’s for fools.” Then he rapped a little bit about the importance of finishing your veggies, and always recycling to the extreme. I bring up Jake’s thievery here because it does, as we’ll see, qualify as a continuity error. I also bring it up, though, as evidence that continuity errors are worth having if they lead to a far better episode than the one it’s contradicting.

I’ll explain that later on. For now, Jake’s mother leaves and Willie sees that ALF has been watching and gleefully masturbating throughout the entire scene.

You may still be wondering why I don’t hate this one, but don’t worry; we’re coming to that now.

The Ochmoneks, Jake’s mother, and Jake are all dining with the Tanners, and as soon as Jake finishes (and his uncle asks for seconds) he says he’s full and they should probably get going.

Josh Blake isn’t a stellar actor or anything, but he does a good job in this episode, and specifically in this scene. His discomfort registers, probably because the kid has never been ill-at-ease in the Tanners’ house before. Whenever we’ve see him here he’s been one of the family. In fact he’s more than that, because people actually seem like him and enjoy his company. If Jake is uneasy it’s because something’s wrong, and that’s clear even if we’re kept in the dark as to what.

Jake’s mother also registers as a significant difference. She’s an unfamiliar presence, introduced at the same time we start seeing Jake behave strangely. And not only have we not seen her before; we’ve not heard about her before, either.

At least, I can’t remember hearing about her. Maybe a bigger fan of the show (Kim? Furienna?) will be aware of some reference I’ve forgotten, but, for me, she appears out of literally nowhere, and this episode answers a question I never thought to ask: why doesn’t Jake live with her?

In “The Boy Next Door” we found out that he was moving in with the Ochmoneks (his aunt and uncle) because his father went to jail. His mother’s status, to my knowledge, was never mentioned. I didn’t bring it up then, and probably didn’t even notice it. This is a TV show, after all, and while watching you fill in many gaps for yourself. Stories have to be brief, and not all details can be covered. You allow that. It’s part of the price of enjoying your favorite programs on a weekly basis.

Jake’s mother was one of those missing details, and “Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow” has fun with that fact: the Tanners and ALF all concluded, independently, that Jake’s mother was dead.

It’s a joke that shouldn’t play as well as it actually does, because that is a pretty shitty thing to say to a kid, but it’s just meta enough that it works. Whether we knew it or not, we all did the same thing.

Jake’s here because his father is in jail? His mother must be dead. Like the Tanners, we didn’t come to this conclusion consciously or rationally…but in the absence of any other explanation, we conclude silently, passively, that she does not exist.

This episode (whose title I’m already sick of typing) takes the previous lack of an explanation and spins it into a pretty good story of its own…and its resolution is one that especially stings when you realize that Jake is more comfortable with people assuming she’s dead than knowing the truth.

Then we get even more fun had with the previous lack of an explanation. When Lynn brings ALF his supper, he theorizes that the woman is an impostor. It’s actually Jake’s father, he says, masquerading as a woman in order to avoid his prison sentence.

It’s stupid enough that it circles around to being funny again, but ultimately it serves a narrative purpose as well: ALF is convinced that something isn’t right, and so he’s attentive to things that the others might overlook. This conversation even leads to one of the show’s better puns, as he quotes a famous Melmacian deli owner: “Something is awry.”

Not sure how well that works in print, to be honest, but I liked it. And Andrea Elson responds with what seems like genuine laughter and — let’s be honest here — a fucking adorable smile, so it’s worth it for that alone.

Back at the table, the Ochmoneks are being the right kind of Ochmoneks. Misunderstanding Willie’s vague comments about ALF to Lynn, Mr. O assumes there’s a problem with the Tanners’ attic. He starts to tell the story of how he used to have an infestation of pigeons: “The place looked like it was stucco’d!”

His wife manages to shut him up, but this is great. It’s convincing. It’s the kind of thing someone might say, thinking he’s telling a funny story, without realizing how disgusting it is, and how the context of a dinner party precludes him from saying anything like that. Again, it’s a lack of self-awareness, which should be Mr. Ochmonek’s distinguishing comic feature. Why? Because this is what works.

Earlier he complimented Kate on the meal, and asked his wife why she said Kate was a lousy cook. Lack of self-awareness again. And it’s still funny.

He asks for more chicken in a moment, but Kate isn’t sure there’s any left. “If not,” he says, “I’ll take a burger.”

And later on, when the Ochmoneks are leaving, Mrs. O thanks Kate by saying, “Several items were simply delicious, Kate.”

These are exaggerated moments, but not by sitcom standards. In reality, it’s some folks who mean no harm but just happen to be bad company. That’s the right way to do these two, and I love it. It’s the only sustained example of handling these characters correctly that I can remember.

Things get uncomfortable when Kate asks Jake’s mother how long she’ll be in town. Jake keeps replying for her that it won’t be long, she’d love to stay, she needs to get back to New York.

Mrs. Ochmonek tells Jake gently that he’s being rude, and should let his mother speak for herself. Jake then tries to explain (convincingly flustered) that he didn’t mean to be rude, and Mr. Ochmonek says, “Cork it, huh Jake?”

It’s a well acted moment all around. It really is. People are being people, and Mr. O being harsh after his wife’s more tactful warning wasn’t effective is a surprisingly good example of escalating tension. I’m not watching a bunch of actors who will never work again pretending to eat dinner; I’m watching human beings interact in a humorous setting.

Amazing what a difference that makes.

Anyway, as all good TV episodes do, this one takes a turn when its main character needs to dump massive ass.

ALF sneaks out of the attic in order to hit the shitter, and when he does he sees Jake’s mother stealing some of Kate’s jewelry. The fact that ALF can’t actually confront her over this is a nice, natural reason that the story doesn’t end here.

It’s not contrived or falsely complicated. There aren’t any fake outs or accusations resulting in them going through her purse and not finding it.

ALF sees it happen, and her actions are unmistakably theft, but he can’t do anything about it. She has to get away with Kate’s brooch, for perfectly organic reasons.

Structurally speaking, it’s not bad. This is one of the (very) rare episodes that I don’t find myself having to make exceptions for.

Afterwards, the party winds down and ALF tells the Tanners what he saw.

This morning, one of my old professors shared an article on Facebook about why it’s nobody else’s business what a woman chooses to wear on her feet. I should like to submit this screengrab of Lynn as my counter argument.

This is one of ALF’s two big scenes in the episode. While I do usually complain about the plot screeching to a halt so that the space alien can do a little song and dance, both of his major interruptions this week actually develop the plot. In itself, that’s good…but even if that weren’t the case, the fact of the matter is that people were tuning in to watch the puppet say and do silly things. A (relatively) dramatic episode about the strained relationship between a supporting character and his never-before-and-never-again-seen mother probably wouldn’t have thrilled most of the viewers, so popping the title character up from behind the couch now and again was probably not a bad idea.

If anything, the fact that I like these scenes proves that there’s no specific formula for what works and what doesn’t. The same thing that annoys me in one episode can entertain me in the next, so long as the writing is good enough. Give me something to enjoy, and I’ll focus on that. Give me nothing, and my mind starts to wander.

Anyway, ALF engages in some pretty decent verbal shenanigans as he breaks the news. As soon as Willie starts yelling at him for waltzing into the living room without the all-clear, ALF does his best to redeem the moment: “Ahhh…Willie! You’re probably wondering why I’ve gathered you all here…”

And when Kate tells him he’s in trouble and not to change the subject, he reflexively answers, “I’m not trying to change the subject.” Then, after a beat, “Okay, I am. But this is really, really good.”

…I fucking like this.

Ultimately Kate goes to check on the brooch and finds out that it’s indeed gone. It’s been in her family for generations, just like everything else they own, apparently, which nobody ever mentions until ALF is caught manipulating his prostate with something for a laugh.

Since nobody apart from ALF saw the theft, Jake’s mother can’t be confronted directly. ALF says that he’ll speak to Jake about it instead. A sitcommy development that is raised in a decidedly natural, non-sitcommy way. Again, people: this is not that hard. YOU ARE DOING IT RIGHT NOW I DON’T WANT ANY MORE EXCUSES

The confrontation between the two manages to feel both realistic and (for the most part) funny. ALF isn’t comfortable bringing up what happened — clearly he knows it will be painful to Jake — so he stalls, trying to get Jake to “go first.” Which obviously doesn’t work, as Jake isn’t the one who called this meeting.

ALF tries to drop hints rather than come right out with it. He says he doesn’t know how to broach the subject. He thanks Jake for stealing some time to talk with him. He doesn’t, after all, want to rob Jake of any time with his mother.

It’s nothing fantastic, but it’s a fun bit of labored wordplay, in which the fact that it’s labored is the joke.

This sort of thing would play just as well on the radio, because it’s built around what people are saying and not saying. Which in turn frees both Fusco and Blake up to perform like human beings rather than flailing clowns. ALF barely makes eye contact, and fiddles with the bedspread as he talks. Jake sits awkwardly, wary of volunteering anything, and only really engages after ALF mentions his mother. It’s here that the boy stands up and says, defensively fragile, “What about my mother?” It’s clear that he knew something like this was coming, but he wanted to be wrong.

ALF tells him that he saw her steal from Kate’s jewelry box, and the look of disappointment on Josh Blake’s face is great. He’s acting. I believe in what he’s feeling right now, and it’s heartbreaking. It’s here that the point of the episode crystallizes. Jake knows about his mother’s behavior already. It’s what he was hoping to avoid anyone else finding out by keeping her squirreled away. And he wanted to believe that she wouldn’t do such a thing to the family that’s been so kind to him…but she did it anyway.

She’s his mother. And he loves her, but he can’t stand her behavior. It’s a sentiment that hits extremely close to home for me, and I’ll be honest and say that that’s, in large part, why I appreciate the episode.

“Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow” isn’t great television. That’s not why it resonates with me. By ALF standards, sure, it’s downright revelatory. It’s far better than the show’s baseline, which is pretty well represented by the episode in which ALF sings about wanting to finish in Lynn’s butt.

It resonates with me because I understand this. Of course, ALF has mined my emotional past for plotlines before, and that didn’t do it any favors. “Tequila” is a good example of taking a subject I should have been on board with, and botching it so spectacularly that I instead came away insulted. This one doesn’t do anything more than say, “Hey. I understand.” Sometimes that’s all you need to hear.

“Tequila” took the approach of preachy, sledgehammer nonsense. In it, ALF appeared to Kate’s soused friend as the Sobriety Goblin or whatever and scared her straight forever and ever amen. I grew up with an alcoholic, and even if the episode ended up being hilarious I’d have had trouble enjoying a conclusion in which the world is set to rights by a sassy puppet.

Here, ALF doesn’t pretend to be The Ghost of Shoplifting Past or anything. He doesn’t solve any problems. (Unless you count getting Kate’s brooch back, but that’s more of a symptom than a problem.) In fact, the main conflict of the episode hasn’t even been overtly raised yet. “Tequila” couldn’t possibly win me over, because its moral was something like “We can fix this.” And any readers out there who were also raised by alcoholics know that isn’t true. It’s an insulting suggestion to victims everywhere, the idea that a problem as serious as alcoholism still exists because you didn’t say or do the right thing to fix it. There’s nothing wrong with making light of a serious issue (in fact, that’s often a healthy way to process it), but there’s something astoundingly wrong with presenting it as being so easily resolved.

“Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow” doesn’t see Jake’s mother fixing a thing. We don’t end with a letter from New York thanking the Tanners for solving everything. She leaves, and life goes on. The bad things keep happening, because sometimes, despite your best intentions, despite all of your efforts, despite how much you need things to change, you can’t stop them. No, not even with a magical space puppet.

I remember wondering as a kid — and I still wonder today — what it’s like to watch those Very Special Episodes if you’ve experienced exactly the topic they’re covering. I guess I have, in some way, my own answer…but I’m curious on a wider scale.

How does that uncomfortable episode of A Different World play if you’ve been the victim of sexual assault? Is it helpful? Is it condescending? It opens a dialogue, but does it do so in the right way? Does it guide the conversation, or just make people more embarrassed to bring it up?

If you were molested as a kid, can you sit through the episode of Diff’rent Strokes in which Arnold’s friend gets diddled by the guy who runs the bicycle shop? Are you glad that people talk about the subject, or do you wish it was raised in a forum that wasn’t overrun with catch-phrases and pat resolutions?

These are rhetorical questions. I don’t expect anyone to answer (though, if you’d like to, remember that you can use a false name and email address below; you can remain completely anonymous).

I remember watching episodes like that growing up and wondering why they bothered. They weren’t as funny. They made me feel guilty to watch, because there I was thinking I was unhappy while sitcom characters endured terrible things that I (thankfully) never had to. Who was I to be sad? But did these episodes make real-life victims less sad? Or did they result in unhelpful discomfort all around? If the episodes weren’t for people who hadn’t been through these things, and they weren’t for people who had, who the hell were we making this crap for? And why?

This episode, though, gets me. It works, as far as I’m concerned. It raises a tricky issue, and leaves it. It doesn’t try to diminish or sanitize the fallout.

Granted, a woman stealing a brooch isn’t as “significant” as alcoholism, sexual violence, or your friend Dudley getting raped by Gordon Jump. But attempting to grow up under (and out of) the shadow of a broken home, of damaging parents, of a family you try really fucking hard to love but who will never change…of people you know you’ll have to leave behind if you’re ever going to save yourself, however selfish or cowardly or unnatural that might feel…of leaving behind all of your friends, your school, your entire world because your very family won’t let you become a better person…that’s heavy stuff. And as someone who’s been there, and as someone who struggles almost every day to push forward, I promise you it’s difficult. Difficult to talk about, difficult to write about, and difficult to carry with you.

Jake’s reactions here are both pained and painful. After he opens up about his mother’s problem, he promises ALF he’ll get the brooch back…and the exchange between these two gets uncomfortably realistic. First, he says he’ll steal it back when she’s sleeping. (ALF replies, “Who are you people? The Capones?”) He tells Jake to talk it out with her instead.

Great sitcom advice. Often terrible real-world advice.

And Jake calls him on it. He tells ALF, bluntly, that he’s been through this. Again and again and again. Yes, he’s a little kid on some dumbass puppet show, but that doesn’t mean he can get through to his mother. It doesn’t mean he can pull the world together in 22 minutes plus commercials. It doesn’t mean that this problem is going to go away next week. He can’t fix her. He has to live with this.

He’s tried. He’s tried hard. He’s done his best for her, to help her. When she came out to visit, he hoped she was going to tell him that she’d gotten better, and turned herself around. Because then, maybe, he could go back home.

But she hasn’t done any of that. Nothing has changed. He’s stuck here, living with an aunt and uncle that he doesn’t particularly like, longing for the New York he grew up in, being reminded in the worst possible way that he’s never going to be able to go back. Through the decisions his parents made, and continue to make, he ended up having to leave if he ever wanted to make something of himself. And now he’s stuck somewhere he doesn’t want to be. His frustration comes through in what’s easily some of the best acting this show’s ever had. (And, I’m positive, ever will have.)

At last, after all of this, Jake says, “I’ve had this fight with my mother a million times.” Then he takes a breath and admits, defeated, “I give up on her.”

And most shows — including many shows better than ALF — would see to it that this conflict is resolved by the end of the episode.

Jake, in some way, will give his mother a second chance, and he’ll be glad he did. He has to. That’s the way these shows work.

But that doesn’t happen.

He gives up on her, and he gives up not because sitcoms work that way (they emphatically do not), but because, sometimes, however painful, however unfortunate, however absolutely fucking awful that feels, you need to give up on someone you love.

You try to help, and nothing changes. You find yourself hindered by who they are, by how they wish to live their lives. It’s a toxic relationship, and you don’t have the ability to change that. There are few images sadder than that of a young boy locking his mother out of his life, but this episode, incredibly, understands that that’s exactly what needs to happen sometimes.

The right answer isn’t always the one that makes you, or anyone, happy. Jake tells us her that he’s given up on her, but his very presence here in L.A. proves that he actually gave up on her a long time ago. All this conversation does is reinforce his decision, and it suggests that he’s made the right one.

And ALF, like everybody else Jake will admit this to (I promise), says, “How could you give up on your own mother?”

And Jake tells him to back the fuck off.

He promised to get the brooch back, which is all he can do, and he storms off.

How could you give up on your own mother?

The question that hurts the most, because the person asking will have already decided that you can’t answer it.

Jake confronts her in the next scene, which is also the episode’s last. One thing I really, really like about “Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow” is the length of its scenes. There are only a few in the entire episode, and it gives the cast a chance to breathe. Its moments are long, dialogue-driven, and largely human. It feels like a stage play at times, in much the same way that “Night Train” did…which was to its credit as well.

A commenter a while back suggested that I seem to like episodes better when they have an emotional component. I don’t think s/he is wrong, but it might not be exactly that; I think I like episodes better when they let the characters act like people. Often, that’s in order to explore some kind of emotion, sure. But not always. “Superstition” is a good example of a very enjoyable episode without any emotional content…but with a lot of human content. And this episode, like “Funeral for a Friend” before it, is an example of one that balances both. I think, ultimately, I just like episodes that don’t insult my intelligence. Whether that’s because it makes me laugh or because I can identify, I’m happy.

Here we have the big conclusion of an emotional episode, and it still manages a few good laughs. As Jake confronts his mother, for instance, he notices that the initials on her suitcase aren’t her own. She covers by saying, “I won it!” and pulls it out of his view, in a really impressive bit of comic acting for this show. It’s a gag, but it’s also a punch in the gut for poor Jake. It’s equal parts joke and characterization.

I looked up Randee Heller — who plays Jake’s mother — to see what else she’s been in, and it’s a lot. Nothing I recognize her from personally, but evidently she was in a bunch of episodes of Mad Men, which I hear somebody somewhere probably liked a little bit. So, yeah, I’m sure she knows her way around a script.

Before Jake can confront her, she tells him that she knows school is almost out for the summer (nice real-world timing, as this episode falls at almost the very end of the TV season), and invites him to come back to New York with her tomorrow.

He doesn’t answer. He’d rather talk about what happened during dinner at the Tanners’ house.

This serves as a nice — though probably unintentional — echo of his conversation with ALF. In each case, neither party really wants to bring up the problem and talk about it. His mother here says that all that happened is that they ate roast chicken. He says, “After that.” She says that they had coffee. Frustrated, he says, “Before that.” She continues to play dumb and even turns it around on him with a sarcastic remark about enjoying this “trip down Memory Lane.”

All while she sees how frustrated her son is getting. Blake is on point here, demonstrating better acting chops than nearly anyone he’s shared the stage with on this stupid show, and is even better than even Anne Schedeen has been lately. It’s legitimately painful to see him here, forced into an uncomfortable conversation with his mother, who is trying to make him feel crazy for accusing her.

When he talked about this to ALF, he was criticized for giving up on his mother. When he talks about it with his mother, he is criticized for inventing nonsense. Jake is in a no-win situation. He’s in this alone, and that’s the most painful thing about it.

Ten years ago, I left New Jersey. I left my job. I left my friends. I left the only world I’d known, and it was the most difficult and painful thing I’ve ever had to do.

But that’s the important thing: I had to do it. It was the only choice I had. The only right one, at least.

I didn’t want to leave. I especially didn’t want to abandon my family. But in a small town, in a small state, in a small world, you may need, at some point, to take drastic measures to distance yourself from your circumstances.

I come from a family in which substance abuse (alcohol I’ve mentioned before; it’s also the most benign example), violence, theft, manipulation, and emotional abuse and manipulation are common. If I were not related to them by blood, I would be able to dismiss much of my family as being, simply, bad people. The kinds of people you’re warned against getting too close to. The kinds of people you should never, ever let make your decisions for you.

But because I am related by blood, the narrative necessarily shifts…and I become the villain.

How could you give up on your mother?

The answer is simple: because you have to. Because you’ve done everything in your power to help. Because you can have these same arguments a million times and nothing will change. Because no matter how much you do, you aren’t that other person. They make their own decisions. And if they continue to make the ones that tear themselves down, and you with them, you need to make a difficult choice. The choice that has a right answer, but has no happy ones.

I started fresh, and it wasn’t easy. It still isn’t easy. There’s not a Mother’s Day, a Father’s Day, a Christmas, a Thanksgiving, an Easter, or even a Fourth of July that goes by without me feeling acutely aware of just what I do not have. What I cannot have. And it’s a pain that doesn’t soften over time. The holidays last year were as difficult as they ever were. This year they will be difficult still, and the year after that. And the best part? That I can’t actually open up to anyone about it. That’s one thing this episode gets exactly right about Jake’s predicament, deliberately or not. He tries to talk about it — twice — and he’s the villain. Twice. Because he did the only thing he could do to become a better person.

I know how this kid feels. I know he isn’t happy. He makes perfectly clear how much he’d like to go back to New York with a mother that turned her life around, but that’s not what’s happening here. He can’t pretend it is. Getting out of that house was probably the smartest decision of his life, and it’s one he’s doomed to regret forever.

Ha ha.

She reacts angrily to his accusation. She lists all the reasons that she couldn’t possibly have taken the brooch. But he knows the truth. He’s not trying to upset her; he’s only trying to return an object of sentimental value to his friends. Instead he gets excuses, delivered sharply, designed to hurt him for even asking about it.

He shakes his head and says, “Nothing’s changed, has it, ma?”

This is the fight they’ve had a million times. He knows. He wants to help. He doesn’t want this to be his life. And she turns it back on him. She knowingly hurts him more than he’d ever want to hurt her.

“Yeah, something’s changed,” she tells him. “You got a mouth.”

When she finally admits she took the brooch, and gives it back while insulting its quality, you can see how much it hurts him. He knew she took it, was fully confident of that fact, and yet you can tell that he was hoping — against all reason — that he was incorrect. That she’d somehow prove or demonstrate that she didn’t take it. That she’s not the woman he had to leave last year. That he was wrong and things could be okay.

That’s what he wants. He doesn’t want the brooch back. He wants to find out that all the crap he’s been feeling, and going through, and struggling against was his own fault. He wants to be wrong. He wants this to be something he can fix. Nobody else is fixing it, so all he wants, the only thing he wants in his life, is to be at fault so that he can make things better. So that he can make everything bad go away.

As painful as all of this has been, and continues to be, for him, the fact is that he would rather be at fault. He doesn’t want it to be his mother. The last thing he wants is for it to be his mother. He doesn’t want to give up on her. She’s an adult. She raised him. He’s a stupid kid still learning as he goes. Why can’t he be wrong? Is that so much to ask? That the adult can be an adult and the kid can be a kid? Why is this so hard?

It’s unfair. It’s unnatural. It’s not the way things are supposed to be. Jake, through no fault of his own, is forced to be an outlier. The kid at Christmas without a family. The kid whose phone won’t ring on his birthday. The kid who, one day, is going to fall in love with a girl and have to share all of this with her, and is going to have to deal with the way she looks at him when she finds out that he cut his family out of his life.

How could you give up on your mother?

All he wants is to be wrong.

All he wants is to see his mother again and realize he was wrong.

All he wants it to find out that this was all a big mistake and he’s the idiot and everything can go back to the way it’s supposed to be.

…but he finds out the opposite. And it’s devastating.

She tries to guilt him into coming home. She says that that would help her get better. Jake — smarter than most would be in this situation, I am sure — knows better. He doesn’t go home. To his own mother, to everybody, he’s the villain.

He has to be the villain. It’s the right choice to be the villain.

But that doesn’t mean it feels any better.

She leaves, and ALF pops up to say he’s been watching and solemnly masturbating throughout the entire scene.

Now that he’s witnessed the way Jake’s mother behaves and interacts with him, he understands Jake’s perspective a little more. He tells a few jokes about how shitty Kate’s cooking is and how shitty Kate’s brooch looks and how shitty Kate is at everything that shitty lady does in her shitty life, and that seems to cheer Jake up a little bit, but I like to see this small moment of emotional uplift as coming because someone now understands what Jake has to deal with every day of his life. It means a lot to know that someone, anyone, is on your side.

This is why I write. It’s how I handle things. Whether it’s fiction or essays or reviews or venom spat at decades-old sitcoms, writing is how I express myself. The internet has helped tremendously with that. Every once in a while I’ll get a comment or an email thanking me for something I wrote. It’s often something I’d forgotten I wrote. Somebody was having a bad day, found some old article of mine, and felt better after reading it. Someone took the time to say thanks…which is a larger gesture than it actually sounds like.

I write because it helps me, but if it helps anyone else, at any point, to any degree, that means everything to me. For that moment, I’m able to forget that I’m a villain. I’m able to forget how much I can’t express. The places I can’t return to. The faces I’ll never see again.

The friends I’ve lost and the opportunities I’ve left behind.

The people I’ve hurt.

The doors I’ve had to close, one by one.

There are things you can’t talk about. Not only because they’re too painful, but because nobody will understand. And so we connect with each other the only way we really can: indirectly.

It means a lot to me to know that anybody reads these things. It means more than I can even express to know that anyone enjoys them. Because while I had to leave a lot of things behind, this reminds me of the other things I’ve found instead. I write. I invest myself deeply in the work that I do. I try my damnedest to raise money for charity. All things I enjoy, but all things that are, emotionally, necessary for me. If I wasn’t able to make certain people happy, I’ve found some small ways to do it for others.

I end this episode feeling very close to Jake. I want to hug the kid, to be honest. Because he’s not a bad guy. He’s someone who has to deal with bigger issues than he should at his age. If he’s a prick now and then, we now know why. We understand.

And we can hopefully forget the fact that he was introduced to us as a thief as well. That muddies the water here if we remember it. If he moved to L.A. to get away from his mother’s behavior — which I do buy — it’s impossible to rectify that with the fact that he was immediately willing to do the same things upon starting his own life. Sure, we could see this as character growth (he went from stealing from the Tanners to returning their stolen belongings) but I can promise you that the last thing you do in a situation like that is slide willingly into the very behavior you left to avoid.

“Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow” recontextualizes “The Boy Next Door,” and in many ways overwrites it. Which I’m happy with, because while the episode gave us an unexpectedly valuable actor, it was also kind of shit.

This is the Jake I prefer. We don’t need windows into his soul like this every week; we only need one. Every time we see him from now on, we’ll understand a little better where he’s coming from.

And that’s fantastic.

…then again, Jake disappears forever in two more episodes. So THERE’S THAT.

Leave it to mother fucking ALF to cap off one of its best episodes, and probably its most affecting, by kicking the central character out the door and never speaking of him again.

Why — why — is it that even when I like this show I have to be reminded of how much I hate it?

In the short scene before the credits Willie silently flashes back to all the shit he saw in Vietnam.

We find out that Jake’s mother left…and took Mr. Ochmonek’s coin collection with her. A joke, yes, but also one that assures us that we aren’t watching “Tequila.” Things aren’t better for Jake’s mother. Things aren’t better between Jake and his mother. Things aren’t better at all. People have problems, and problems — as much as we’d like them to — don’t always go away.

Things are still as they are.

It’s another day, and though that brings with it no promise of change, it’s also the most reassuring thought we have. The sun, as they say, will come up tomorrow.

Thanks for seeing it in with me. It means more than I can tell you.

Countdown to Jake ceasing to exist: 2 episodes

Countdown to Jim J. Bullock existing: 10 episodes

MELMAC FACTS: We learn that Jake’s mother is an Ochmonek “by marriage,” which means his father is the brother of either Trevor or Raquel.