Boy, I hate Mega Man 8.

I’ve played worse games, of course. Plenty of them. In fact, if I made a list of the 50 worst games I’ve played, Mega Man 8 probably wouldn’t be on it. But I do truly hate it.

I don’t hate bad games, usually. As I’ve discussed before, I like junk. I like trash. I like watching the wheels fall off. There’s a giddy thrill to that which holds genuine appeal for me.

Mega Man 8, though, I hate. It’s not “fun” bad. It’s “tedious, irritating, pointless” bad. In fact, if it didn’t have the Mega Man name attached, I don’t believe there’s any chance at all that it would be remembered today. It doesn’t stand on its own merits, it isn’t entertaining, and it absolutely is not worth playing.

I honestly expected that the game would grow in my estimation this time around. I’d played it a handful of times before, at least once to completion, but here, now, for this series, I’m opening myself up. I’m digging deeper. I’m finding things I’ve never found before and, as I’m forced to articulate my opinions, I’m learning that I sometimes feel differently than I thought I did.

But Mega Man 8 is the same old game I’ve hated for years. If it’s grown in my estimation it’s only done so by some negligible amount. The one thing I can say for sure is that I’m reminded of all the reasons I pushed it away in the first place.

This is probably the right time to mention that I never had a PlayStation. That console hit its peak when I was firmly in the Nintendo camp, and its superior successor arrived when I had more or less stopped playing video games altogether.

Is that the reason I missed out on Mega Man 8? I’m going to say no, since I also missed the two previous Mega Man games the first time around. The series had lost its grip on me. Perhaps if I had owned a PlayStation I would have gotten Mega Man 8 as a gift at some point. But I doubt I would have sought it out. And if I had…man, I would have wished I hadn’t.

I grew up with Nintendo. For me, it wasn’t a company…it was a promise. The video games they made — and the games released for their systems — were escapes for me. Many years later, literature would scratch that same itch, and far more deeply. But when I was young, when I had little to look forward to and a lot to run away from, video games were an important coping mechanism. I could pick up a controller and have a say in what happened. I could try again and again to beat the same level, and eventually triumph. I could start out weak, and end up strong. The Mega Man games were probably the perfect distillation of that mindset, and I believe that’s why they resonated with me so strongly.

And, of course, I didn’t think of “video games” as being my escape; I thought of “Nintendo.” It’s a name that still, to me, sounds like the name of a friend. I had an Atari, but it didn’t grab me the way the NES did. Or the Game Boy did. Or the Super Nintendo did. I got a Nintendo 64 as well, and I loved it, but at some point during its lifespan I found myself with less time to play and less interest in what I was missing. I didn’t turn my back on Nintendo…I just lost touch with my friend.

I was aware of the PlayStation, but, to be frank, it never impressed me. Not back then. That’s an opinion I’ve been fortunate enough to revisit much more recently, and I like the console now. Back then, though…I didn’t really see the appeal.

I remember the controller feeling awkward to use, which is something I’m sure I was not alone in; it was redesigned relatively quickly. I remember the offputting fact that the games came on CDs. I was used to playing CD-based games on my computer, and was already well familiar with how easily they got scratched and how temperamental the reader could be. I remember those early PS1 graphics looking…well, terrible. The colorful worlds I expected in video games were replaced with darker, murkier textures that looked neither realistic nor inviting. And so I played some PlayStation games with friends, and I had fun, but I never felt as though I was missing out by not having one.

Until I played one game: Resident Evil.

Playing Resident Evil the first time was one of my formative gaming moments. I remember my friend Mike bringing it over. I remember passing the controller back and forth with him and my other friend Dave. I remember the thick, visceral tension we felt as soon as we booted it up.

While this doesn’t sum up all of the feelings about Resident Evil I had that night, it’s worth emphasizing one thing: it scared the living crap out of me.

It’s silly to look back at it now that its cutscenes and writing and voice acting have been eviscerated mercilessly, but back then…I guess we just didn’t care. I still remember thinking those things were terrible — we were already in the habit of watching bad horror movies, and Barry’s delivery of the word “blood” alone had us rolling as hard as any of those films did — but somehow that wasn’t important. Maybe the acting was terrible, but was that really what mattered? We’re trapped in a mansion full of zombies and intricate death traps. Any laughing relief we get from that is bound to be fleeting; around the next corner we might have to use our last two bullets against a monster that will kill us anyway.

Resident Evil is the game that convinced me the PlayStation had merit, simply because it did something no other game had been able to do. No, being frightened wasn’t high on my list of priorities while gaming, but the fact that Resident Evil could elicit that response from me…could trouble and upset me psychologically…could tap into a part of my brain I had never truly had tapped by a game before…that meant something.

Of course, Resident Evil was developed be Capcom. And I’m currently playing through The Disney Afternoon Collection on my PS4, which is reminding me of just how important Capcom was to my experience of the NES. More than any other developer, I think, Capcom defined video games for me. It defined my expectations. It defined my sense of level design and progression. It defined my taste in game soundtracks. It defined what it meant to play. And then, years later, with Resident Evil, it defined so much all over again.

I love Capcom. Whatever silliness and shenanigans they may get up to today, they’ve earned a permanent place in my heart by creating a huge percentage of the games I remember fondly.

All of which is to say, if anyone could have given the world a great Mega Man away from Nintendo’s consoles, it was them. They understood the formula. They proved with Mega Man 7 that the aging series had life in it yet, and they proved with Resident Evil — in the same year as Mega Man 8! — that they could provide compelling, defining, important games for that generation’s unexpectedly successful new console.

What they produced instead was a game I hate.

And nobody’s more disappointed by that than I am.

Funnily enough, the one thing I really enjoy about this game is the one thing for which it’s most often reviled: the animated cutscenes.

I’m not saying they’re good. In fact, let’s clear that up right now: they’re absolutely terrible and they deserve the mockery they’re destined to receive through the end of time.

Having said that, though, I enjoy them. They’re silly, cheesy, cheap, and poorly acted. Which is…pretty much exactly what I hope for whenever I crack open a movie that looks terrible. There’s an appeal to genuine garbage, and Mega Man 8‘s animated sequences occupy an incredible sweet spot that only the truly best of bad entertainment can achieve.

Despite the fact that I didn’t play this game upon release, those cutscenes still hold nostalgic value for me. In late high school, Mystery Science Theater 3000 was cancelled by Comedy Central. The Sci-Fi Channel bought up the rights, and aired it early on Sunday mornings.

I’d wake up, turn the television on, and enjoy one of my favorite shows. Then, after that, they’d show an anime film. And, here’s the thing: it wasn’t good anime.

I don’t remember any specific films they showed, so I’m afraid I can’t offer much in the way of context. Suffice it to say this was years before Adult Swim used Cowboy Bebop to teach Americans that anime might be worth watching. The Sci-Fi Channel was, I’m sure, just plopping something cheap into a timeslot before the bulk of its audience woke up. And so we got poorly dubbed, poorly animated, slapdash wastes of time instead.

And I loved them. My friend Nate and I both enjoyed Mystery Science Theater 3000 and found ourselves transfixed by whatever silly, forgettable anime garbage followed. We’d talk about it the next day in school. And watching the cutscenes in Mega Man 8 reminds me of that. It reminds me of watching those films and mentally preparing notes to share with Nate. It reminds me of laughing with him in the hallway. Had either of us played this game back then, I’m sure we would have tracked the other down as quickly as possible and forced them to play it. It was just the right kind of bad when it came to those sequences.

Replaying it for this review, I think I laughed harder than ever. It’s truly incredible stuff. The legendary speech impediment of Dr. Light is topped only by the same actor’s inability to get any of his lines right, resulting in stumbles that are, for some reason, left in the final edit. There’s Mega Man’s idiotic mispronunciation of Bass’s name. (As well as Bass’s masterful rejoinder: “Shut up.”) There’s Duo, whose voice actor seems to have recorded his lines in the middle of the night while trying not to wake his sleeping grandmother.

It’s gloriously bad.

The story this time around is fairly involved, by Mega Man standards. There’s some kind of unexplained intergalactic clash between opposing forces of good and evil. Good wins — which is nice — but the conflict sends a batch of “evil energy” to Earth, where Dr. Wily finds it before Mega Man does. From there it’s eight bad robots and a fortress…the same melody as ever…but at least it’s not Wily in cataract glasses being handed the keys to the Death-mo-tron 2000 by an increasingly moronic Dr. Light.

Introducing the conflict as an external force that Mega Man must then fend off from his home turf is a smart move, and it makes the stakes feel somewhat higher. We know Mega Man can topple Wily. He’s done it how many times now? But the dark energy from beyond the stars is an unknown quantity. The fact that the game does nothing with that (you can remove it entirely from the plot and nothing would change) is a bit disappointing, but it still makes your task in the game feel larger and more important than it actually is.

Thinking about the story reminds me that there is one other thing I like: THE END CREDITS.

…I’m actually not saying that as a punchline. I really do like the end credits. They include scans of the artwork submitted for the Robot Master design contest that was held for almost all of the original Mega Man games. Fans would send in their creations, and the developers would choose the winners, redesign them, and include them in the game. I’m a bit hazy on the details, but I’m pretty sure the competitions were Japan-only, with the exception of the one for Mega Man 6, which — in nice keeping with the theme of the game — allowed Robot Master submissions from all around the world.

The competition for this game, from what little I’ve read, included some guidelines. They wanted one Robot Master to have long arms, another to have two heads, and so on. Fans came up with their ideas, sent them in, and we see a bunch of those actual submissions as the credits roll. It’s pretty adorable and the one true touch of personality to be found anywhere in the game. It’s also a nice use of the CD format; including actual scanned picture files isn’t something you could do on a cartridge.

And that’s…it. Amusingly bad cutscenes and charming fanart. Mega Man 8 offers little of value beyond that, and it’s one I rarely feel compelled to return to. When I do, I am reminded quickly of why that is.

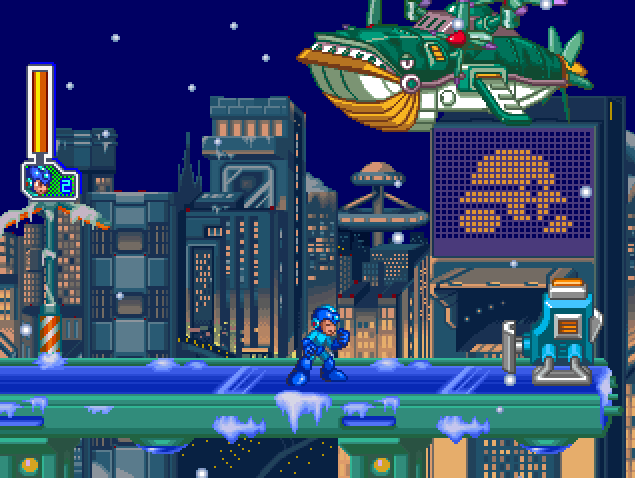

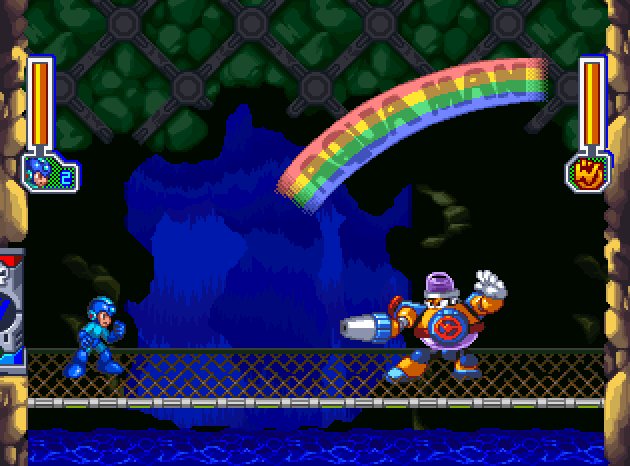

Part of the problem, to me, is that only around half of the stages feel like Mega Man stages. (This is the same problem that plagues some of the Mega Man X entries as well.)

A Mega Man stage is built around a few things: platforming, fighting/avoiding enemies, and experimenting with special weapons. A truly great stage makes all of those things feel natural and fun, as well as challenging. In fact, when you think about Mega Man — any game, any stage that comes to mind — you’re probably picturing something that’s right in line with that basic framework.

You’re probably not picturing stages like we get here, with shoot-em-up sequences, endlessly scrolling cyber mazes, and memory-based rocket sled segments.

Those things aren’t Mega Man, and I think it’s important to note that the one time we did have a stage-based genre bend prior to this (Wave Man’s wave bike in Mega Man 5) it functioned almost identically to what we know of the Mega Man formula. The vehicle was a kind of ingenious illusion. You were still jumping and shooting. You were still playing a Mega Man stage. The presentation tricked your mind into believing it was something else. Granted, you couldn’t use special weapons in that section, but it was basically a single autoscrolling room that in no way worked against your understanding of what Mega Man is or what it expects from you.

I know it sounds like I’m complaining about variety, but I’m really not. What I’m complaining about is the implementation of that variety.

When a game in one genre crosses temporarily into another, it should by and large remain true to what the core experience of the game is. We can — and should — expect variety in our games, but it needs to be a natural and organic variety, rather than a cumbersome, forced Frankensteining.

A few examples may help. In the final stretch of Kid Icarus, protagonist Pit sprouts wings and the game goes from being a (fairly) standard platformer to something more like a shoot-’em-up. But the principles of the core experience remain. You’ve been trained by the previous levels to understand the patterns with which enemies swoop across the screen, the action of your projectile remains comfortable and familiar, and in practice the only true difference is that you no longer have to worry about slipping into a bottomless (and lowercase) pit. It feels like a genre shift, and it is a genre shift, but it’s one that’s so natural all it does is remove one of your previous mortal concerns so that you can focus more directly on the final battle. It’s a genre shift that is also an empowering and effective narrowing of focus.

There are also the turret sequences in any number of action games. Half-Life 2, The Last of Us, and pretty much any 3D action shooter at some point. These moments find your character behind a powerful, heavily armored, stationary firearm, and they turn the game, temporarily, into a classic-style arcade shooter. Again, though, it’s a natural shift and it narrows the focus. You no longer have to worry about taking cover, about health, about navigating the environment, about looking for secrets, about managing inventory, or anything else. After however many hours of doing those things, you get to hunker down behind some heavy artillery and mindlessly mow down the very same enemies that have been making your life miserable. Joel or Gordon Freemen or whomever else you happen to be playing as gets a bit of a rest, you as a player get some important catharsis, and then you’re back on the road.

On the less organic side of the coin, you have things like the street race in Chrono Trigger, or the various shooting galleries in the Legend of Zelda’s 3D era. Those are shifts that, quite simply, aren’t integrated. One kind of game stops, and another, completely different, kind of game begins. The steady grind and increasingly bleak atmosphere of a profound, complex RPG gives way to an underwhelming echo of Excitebike. The careful combat of Link’s adventure — in which every swipe of the sword and raise of the shield matters — gives way to a sudden requirement for speed and accuracy. In each of these examples, the shift is something for which the game has not prepared you and which will prepare you in no way for the rest of the game to come.

It goes without saying that Mega Man 8 falls into the latter category. And, as with the examples listed above, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the genre shifts themselves are bad or unenjoyable. Rather, all it suggests is that they’re poorly and gracelessly implemented.

Then again, they are bad and unejoyable, so nevermind.

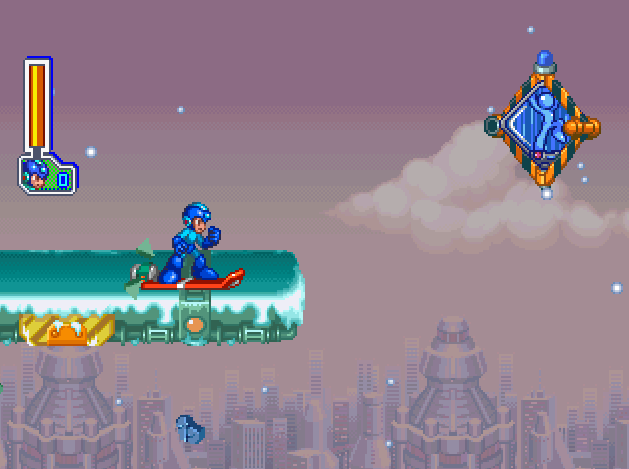

The best of them is easily the Rush Jet section in Tengu Man’s stage, probably because it’s the most straightforward and intuitive. It’s not miles removed from the wave bike, so while it may take a few seconds to adjust to having vertical movement, your instincts as a Mega Man player will serve you decently well as you gun down waves of flying enemies. It still doesn’t feel right or much like a Mega Man game, but it’s simple and inoffensive enough. Additionally, the integration of assist characters leads to some fun cameos, giving Auto and Eddie a chance to fight for the first time ever, and letting Beat get aggressive one last time after his demotion to pit-rescue utility in Mega Man 7.

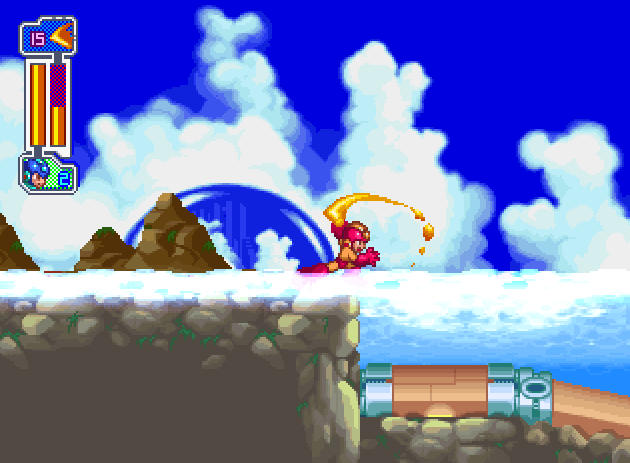

The worst of them, just as easily, are the rocket sled sections. We’re introduced to them in Frost Man’s stage, and beaten mercilessly by one in the first Wily stage. These turn Mega Man — a careful, experimentation-based platformer — into a frantic, twitchy, perfection-demanding chore. It’s essentially a version of the Turbo Tunnel from Battletoads that barks instructions for each upcoming obstacle instead of showing them to you ahead of time. (Battletoads. Now there was a game that could hop genres.)

Often, Mega Man fans will impose upon themselves additional limitations to find new ways of enjoying the game and increasing the challenge. This can take the form of speed runs, no-damage runs, Buster-only runs, Kirby runs (which see players using only the most recent special weapon they obtained) and more. I’ve done a few of these myself, and, in fact, I’ve been thinking for years about attempting a run through Mega Man 10 without using the Buster at all. (Which is only possible there due to the inclusion of the bonus weapons* you get from DLC stages.)

In a way, the rocket sled sections feel a bit like one of those challenges. It’s a speed run married to a Buster-only run…and while you can take damage, you sure as hell don’t have much room for error. The sections scroll quickly and if you miss a jump or end up pinned against a wall, you’re starting over. But the difference, of course, is that those kinds of challenges are optional. They don’t appeal to everybody, and that’s for good reason; they’re artificially difficult. The artificial difficulty of the rocket sled sections — with the infamous, interminable, and completely unhelpful JUMP JUMP SLIDE SLIDE narration — is mandatory, and it makes Mega Man 8 feel a lot less fun.

Mastering a game to the point that you can play it perfectly is a satisfying journey that unfolds over a long period of time. Mega Man 8 demands it out of the gate. That’s not satisfying; it’s obstinate.

And while the argument could be made that the rocket sled in Frost Man’s stage prepares you for the one in the first Wily stage, the fact is that it doesn’t. Wily stages have always abided by the philosophy of testing what the player has learned. Nearly always, that has to do with platform and enemy behavior; it’s up to you to remember how these things work from your earlier encounters, and failing to prove that you do remember will have a stiff penalty. In other words, you see a platform or an enemy, and you don’t get to “learn” how to handle it; you already should have learned, and now it’s do or die.

The rocket sled, though, doesn’t work the same way. A player can’t see it the second time and understand how to handle it, because “handling” it boils down to obeying a rapid series of barked commands. That’s it. There’s no amount of preparation that can help, and the window between each command and the moment you should execute it varies just enough that you can’t develop a reliable rhythm. You just need to listen, attempt, and fail every single second of the segment. Eventually you’ll make it through, if you even want to, but that won’t be because you mastered anything. It will be because you memorized or lucked into the right pattern. Then there’s the fact that jumping seems to have an odd delay in these sections, which means you actually have to hit the button just before you need to jump…

It’s awful. I can’t say enough about that.

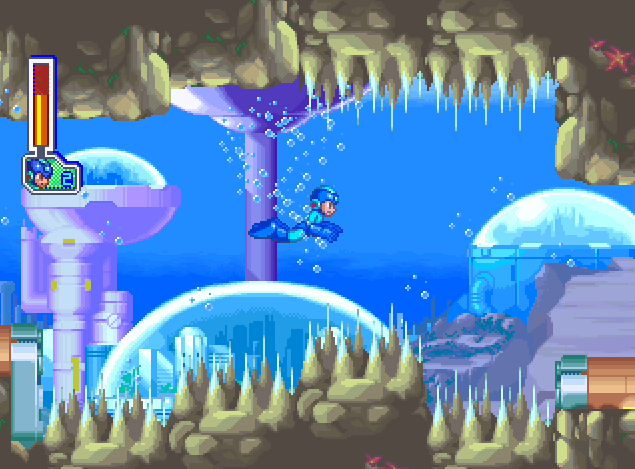

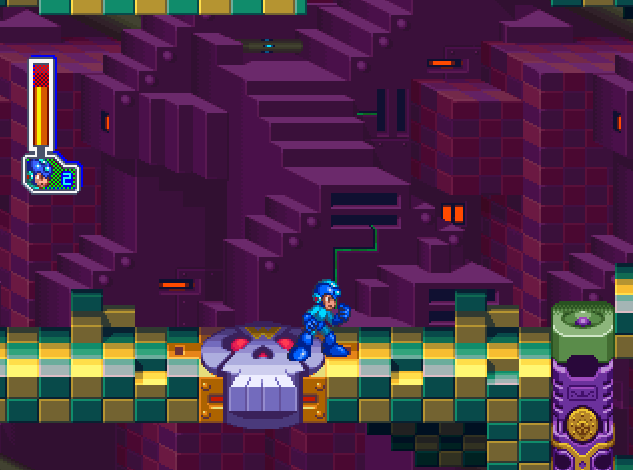

Two other stages have less obtrusive gimmicks. One of which I basically hate, but the other I like a lot. In the former category, we have Astro Man’s stage. And, to be honest, it’s kind of a cool idea.

The stage is broken into three smaller types of stages, which themselves are each repeated in the same sequence. We start with a straight platforming section, then there’s an endlessly looping maze, then there’s a race up through a collapsing tower. After that, we get more difficult reprises of the platforming, maze, and tower sections.

In theory, I like that quite a bit. Teach us a few things, then test us on what we’ve learned. That’s good. Break down a long stage into a series of memorable setpieces. That’s good. Use three gimmicks in compact ways instead of padding each of them out into their own stages. That’s good.

Which means it must be the execution where it falls down.

None of these sections are especially fun, and the maze is irritating and out of place. Once again, it’s not the same genre as Mega Man. Players aren’t used to large, complex rooms without a clear path forward.

No aspect of it is fun, and nothing is communicated well. Colored switches control similarly colored gates, which is fine, but a green switch may control one green gate and not another green gate, making what should be a clear cause-and-effect relationship feel needlessly hazy. Gates can open up passages that can only be accessed by looping through the maze again, but players may stumble mindlessly around for an extremely long time before they realize the maze loops at all. And throughout the entire segment, there’s no clear indication of what you’re even looking for. Eventually you’ll find a skull-shaped indentation in the floor, and the maze is over. But if you don’t know that that’s what you’re seeking, it’s impossible to feel like you’re making any progress; you’re just wandering until the game lets you stop. That isn’t any fun.

I will give credit to Astro Man for introducing a new stage type, though. Once you get complacent with air, water, fire, and ice stages, it’s refreshing to toss cyberspace into the mix. It’s not a stage I enjoy, but it does lay the groundwork for more successful implementations of the theme, such as Sheep Man’s in Mega Man 10 and Cyber Peacock’s in Mega Man X4.

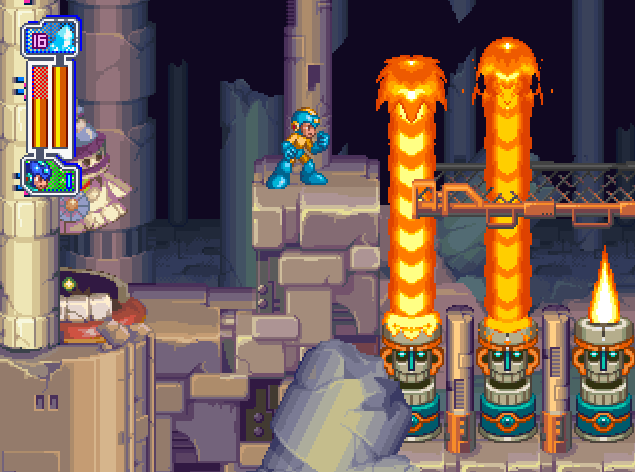

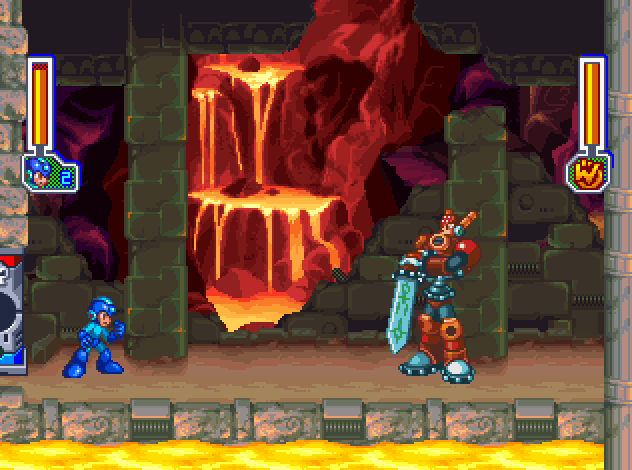

The other gimmick that works much better comes in Sword Man’s stage, which quizzes you on (and helps you develop) your knowledge of the first four weapons you’ve collected: the Ice Wave, the Flash Bomb, the Tornado Hold, and the Thunder Claw.

This is a concept that wouldn’t have been possible prior to Mega Man 7. While I don’t personally like the idea of separating the eight Robot Masters into two groups of four (which would never happen again after this, though Mega Man & Bass somehow came up with a worse idea), it does allow stage designers to rely on the player having certain items in their inventory. Here, they turn the first half of Sword Man’s stage into a test of your worthiness, as though Sword Man won’t deign to face a nobody.

The stage begins with four rooms that are each themed around a special weapon, which is nice for two reasons. The first is that this encourages players to actually use special weapons. I gave up on using them somewhere around Mega Man 4, as they simply didn’t feel very fun anymore. As a result, I’m sure I’ve missed out on some good times and fun moments playing around with them. Thanks to Sword Man, I actually do tool around with half of Mega Man 8‘s arsenal. As a bonus, Sword Man’s weapon — the Flame Sword, with a hilariously pronounced W — is worth using on its own, which means I actually get at least some mileage out of five weapons. That’s a pretty good ratio.

The second is that it helps players to feel empowered in ways beyond strength. Typically special weapons are worth using because they’re powerful, and can therefore take enemies out more quickly. Here, their power is irrelevant; you’re using them to light rooms, remove obstacles, steer objects, and throw switches. It’s rare that a Mega Man weapon feels like something more than a weapon, but in this stage that happens four times over. It provides ways to solve problems that aren’t reliant upon wholesale robot slaughter, and that’s admirable.

Sword Man is overall a highlight of the game. I love the concept of his stage, I love the weapon he gives you, and I love his battle, which feels as much like a duel as any of the best fights in the series ever have. (His fight is right up there with Ring Man and Freeze Man, as far as I’m concerned.) He also seems to have personality, which is something oddly lacking from a game with voice acting and more complex animations.

In fact, they seem to me to have less personality than the Robot Masters from any previous game. This might be an illusion, but it’s an instructive one. See, in the 8-bit era especially, gamers were required to do more than take what was presented to them; they had to fill in the gaps. The graphics were fairly crude, and often blocky and undetailed. Creating appealing visuals under these restrictions was a genuine art (and a number of games achieved it), but it was up to the player to look beyond the representation to the concept of what was being represented. The same goes for the aural presentation. There were no real instruments involved in any NES soundtracks, but if you ever “heard” a drum, a guitar, or a piano, you were meeting the game halfway.

This applies to less obvious aspects of the games as well. Beyond what we see and hear, it’s what we expect to see and hear. What does a character sound like? How does his mind work? Is he brave or reluctant? Is he learning his craft or has he mastered it? These things matter, because they change the story and therefore the experience. Playing as a professional and playing as a gradually smarter amateur lead to completely different game experiences. It’s why Maniac Mansion felt different from Sweet Home. It’s why Darkwing Duck felt different from Batman.

Those games left a lot of blanks for players to fill, and they left them largely out of necessity. There’s no room on an NES cart for voice acting, orchestrated soundtracks, and elaborate cutscenes. These were games in which “jump” and “shoot” constituted the lion’s share of interactivity throughout the entire library.

Eventually, though, we made it to the PlayStation era, with its CD-based media that did allow these things. Gamers responded well to them, and developers were, almost overnight, keen to include them. Now we can hear Mega Man’s nemeses as well as see them. Now we can watch them move with greater detail, which should give us a stronger idea of who they are. Now they can do more than launch projectiles and hop around getting shot to death.

But that ends up being a new problem rather than a solution. Because without those blanks left for players to fill in, they’re exposed as being hollow and without personality. They may look and sound better (both of which are debatable, but they may) than their NES counterparts, but they don’t look and sound better than what we saw in our minds as kids. It’s a step down. It removes the ability to use your imagination and fills in the gap with concrete rather than anything of creative merit.

Leaving little or no room for imagination isn’t always a bad thing, but it depends on what the developer wants to do. I don’t get to argue with my friends about what I think Nathan Drake looks like and sounds like…because there’s a definitive answer, and that definitive answer in no way cheapens the game or makes it more disappointing. But Uncharted — and the developers behind it — understand Nathan Drake well enough that we don’t wish we were filling in the blanks ourselves. In fact, we prefer being in the game’s hands, letting it unspool personal history at its own pace, letting it provide us with better jokes and more clever setpieces than we could imagine, letting it take us on a fully scripted, fully prescribed adventure with almost no detail left unprovided. That’s what Uncharted wants to do, and it does it well.

Mega Man 8 just provides a standard Mega Man experience, though. The fun of the series isn’t seeing where things go, because they don’t go anywhere. The fun of the series has always been the adventure we have in our minds. Mega Man 8 removes it from our minds, and places it instead on the screen, where it feels unexpectedly dull and lifeless. The characters talk, but they have nothing to say. Long animations play out, but they show us nothing of interest. The characters move more realistically, but we’re never given a reason to care about them or be interested in them. Even the winking, sweet comedy of Mega Man 7 is gone. Mega Man 8 is a game that carries itself with deathly seriousness, but without any sense of purpose.

Sword Man, again, is an exception, and possibly an accidental one. Capcom never fleshed out their ideas for who these Robot Masters are beyond extremely broad strokes, so they gave them some vague lines and hoped that would be enough. The bosses announce their attacks. They taunt. They express dismay when they’re defeated. None of which adds to the game in any way at all.

Except that Sword Man actually got some lines and animations that made him feel different. He bows to you before the fight, which is an unexpectedly honorable thing for a Robot Master to do. He compliments you on your skills if you avoid his attacks. And his entire stage, again, feels like a test of your mettle. In short, he doesn’t just fight a doomed battle the way most Robot Masters do. He engages with you as a player. He responds to your actions. He makes you feels as though what you’re doing makes a difference. That’s something the new technology of the PlayStation allowed for the first time in the series…and yet it’s only on display in one fight. That’s deeply disappointing.

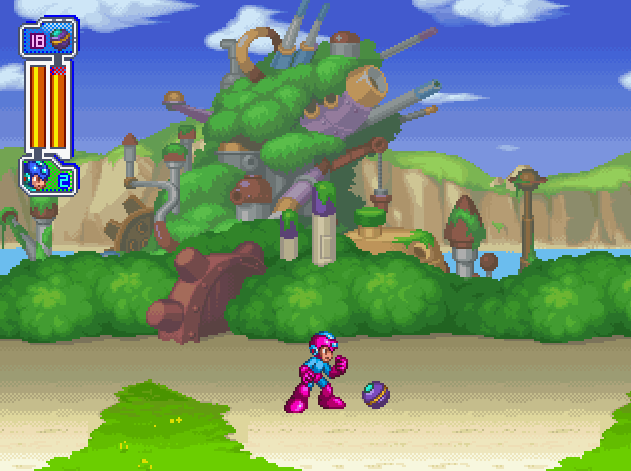

There are some attempts made to spice up the formula, and that’s a good impulse, but I don’t think any of them work. The first and probably most obvious is the introduction of the Mega Ball.

In a very general sense, it’s a great idea. Dr. Light gives Mega Man a new weapon right out of the gate, meaning the player has two things to play around with before defeating any Robot Masters. This does, in theory, keep things fresh; by now we’ve had seven numbered games that familiarized us with the Mega Buster. Surely people playing Mega Man 8 know it inside and out, and can afford to direct their attention to a new gadget instead.

The problem with it is that the Mega Ball just isn’t fun to use. It plops a little sphere in front of Mega Man, which he can then kick upward at an angle. If it hits a wall or ceiling, it will bounce. And that’s…not really exciting. For a series that’s given us massive amounts of spinning blades, exploding bombs, waves of fire, powerful electric arcs and God knows what else, “here’s a soccer ball” doesn’t really spark enthusiasm. It’s an awkward and cumbersome addition to Mega Man’s arsenal that I never bother using…and I’m sure I’m not alone.

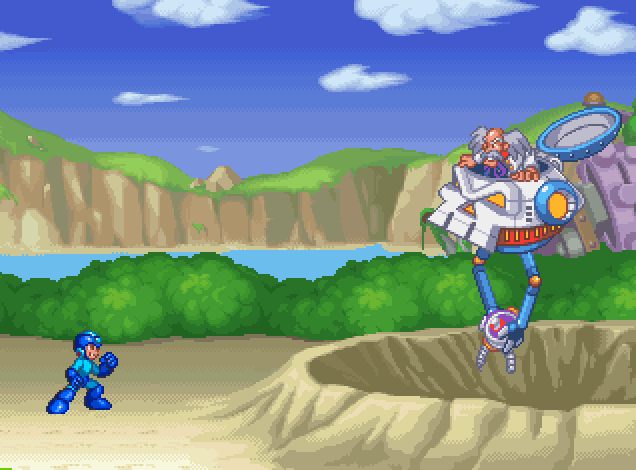

If that were that, it would be easily enough forgotten about, meriting a footnote at best. Instead, though, Mega Man 8 seems to believe that players will love the Mega Ball so much that they’ll spend entire sessions learning how to use it, exactly how it behaves on rebounds, how to predict several angles of trajectory into the future. As a result, the first Wily boss can only** be damaged by it, forcing its usage. What’s more, though, the boss descends temporarily down one of four very narrow chutes, meaning you’ll need expert aim and speed to hit it. It’s a test of mastery with a weapon the game never previously encourages you to play with.

That’s a real problem. The Mega Ball should be implemented throughout Mega Man 8 if it’s a mandatory key to escape the first Dr. Wily level. The game should be teaching you regularly to use it, to understand it, and to rely upon it. Enemies should be placed in positions that immediately suggest it as the best possible tool to take them out. Switches that release goodies should be placed in tight passages so that the player learns the angles at which the ball will travel to reach them. At the very least, a Robot Master or two should have the Mega Ball as a secondary weakness. Instead, it does only one unit of damage to all of them, actively discouraging players from learning how to use it during tense and frantic boss fights.

This is inexcusable, as the game clearly knows that it has opportunities to test players on weapon knowledge. Sword Man’s stage, once again, does exactly that four times over. But the Mega Ball never gets a workout, and then, suddenly, needs to be the most familiar weapon in your arsenal. That’s absurd and idiotic design.

Oh, also, if you lose all of your lives to that boss, there’s no checkpoint anywhere in the level for the first time in the game. Which means you need to do that maddening rocket sled segment again. So, have fun replaying the worst stage in Mega Man history.

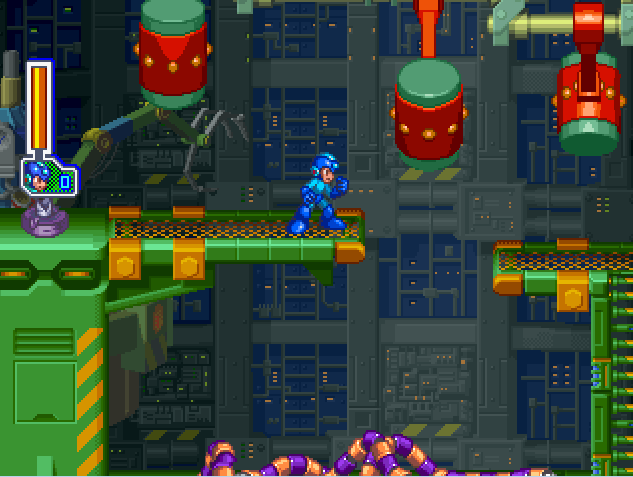

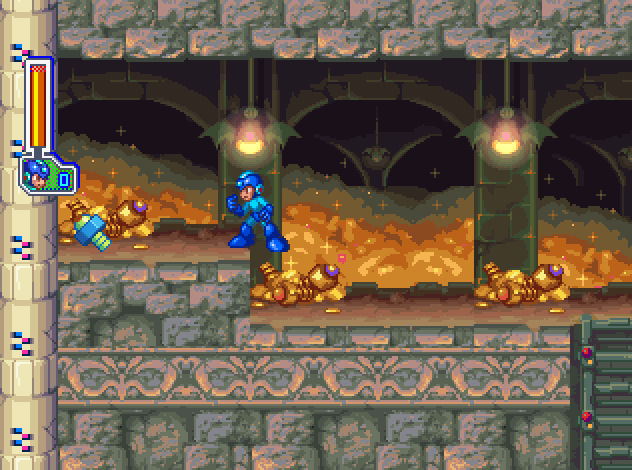

Rush’s role is reimagined for the first time in the series, which, again, should keep things fresh. Rush Coil is gone completely, for the first time since the character’s introduction, and Rush Jet can’t be summoned at will, being usable only in two stages. These aren’t inherently bad things, but the replacement transformations are underwhelming to say the least.

The only Rush transformation that assists with mobility is the Rush Bike. But there’s very little cause to use it and no areas that encourage it, apart from it being necessary to reach a single bolt in Clown Man’s stage. Rush Bike*** is unwieldy and unuseful. It allows Mega Man to traverse long, straight stretches of road quickly, but those barely exist at all throughout the game. You can conceivably use it when navigating platforms, but why would you want to be on a clunky motorcycle in those situations anyway? It’s easier and infinitely more convenient to not use it.

The other transformations are even worse. There’s Special Rush, which sees Rush sometimes giving you an item at random, and sometimes standing there doing nothing. It’s literally never worth bothering with, as the odds of you getting an item you actually need are very slim, and killing any given enemy can generate an item at random anyway. Then there’s Rush Bomber, which carpet bombs an area for you, but since you can’t control where the bombs land it’s far from a reliable way to clear a screen. Finally there’s Rush Charger, which operates the same way but drops healing items. That, sadly, is this game’s replacement for E-Tanks. If you ever wished you could trade a full and easy heal for the opportunity to watch a dog dump small energy pellets over spike pits and into inaccessible crannies, Mega Man 8 is sure the game for you.

The game also attempts to redefine the shop concept from Mega Man 7. That game allowed you to collect bolts from defeated enemies and in caches throughout the stages to redeem at Auto’s shop for useful items, such as E-Tanks or extra lives. Here, the concept is much different. Enemies no longer drop bolts; rather there are a small, fixed number of them scattered throughout the game, and grabbing them often involves miniature environmental puzzles. This isn’t a bad idea, but there are actually fewer bolts in the game than are necessary to buy all items in the shop. And this time, those items are unique upgrades for Mega Man that affect his Mega Buster, his knockback, and his…erm…ladder climbing speed. That means that Mega Man 8 is the only Mega Man game that is actually impossible to complete 100%. You can collect all the bolts, but there will always be some upgrades left on the shelf when you redeem them.

There’s also the moronic fact that the Exit Module — which allows you to leave completed stages — costs bolts…and the only purpose to revisiting stages in this game at all is to find bolts. Why in the world would you scour the world for bolts just to buy an Exit Module that allows you to go back and find more bolts to replace the ones you just spent on that piece of crap? There’s no other purpose for it!

Mega Man 8 also treats checkpoints in a way that I don’t especially like. In previous games, you’d simply, silently, unknowingly cross some invisible line in the stage. If you died beyond that line (and had another life, natch), you’d restart at the checkpoint. Easy enough. Lose all your lives and you’ll have to start again from scratch.

This game, however, throws up a loading screen letting you know that you’ve hit a checkpoint, which breaks the flow. It also fully refills your energy, which means there’s less incentive to play carefully, as you can count on a full mid-level recharge. This makes the miniboss fights that precede many of these checkpoints feel like mindless button mashing. There’s little point in learning their patterns and reacting gracefully if you can just brainlessly tank damage and end up with full health anyway.

Also, why does the game have to take a break to load the second half of the level? To be brutally honest, there’s no way in hell Mega Man 8 pushes the limits of the PlayStation in any way. The previous games all load lightning fast, and pushed their respective hardware far more than this game does. I understand that CD-based media will take longer to load, but there’s no reason a level can’t load in its entirety from the stage select. Stopping the level partway through so that Mega Man 8 can try to remember what comes next is embarrassing.

The worst part, though, is the fact that if you lose all of your lives, you can restart at that checkpoint. That discourages mastering the stages, making the experience feel much different from what the previous seven games provided. In those games, it was important to learn the placements of every enemy and obstacle, because it was a long way to the boss doors. In Mega Man 8 you just have to limp past a checkpoint, and then you’ll never have to worry about them again. It cuts the player far too much slack in a series built around gradual mastery.

In previous games, you could certainly get lucky enough to navigate a stage without learning it. But then if you lose your last life to the boss, you’ll have to start over, and luck won’t serve you as well the next time. You still have to learn. For Mega Man 8, being lucky is enough. You never actually have to learn a damned thing if you’re patient enough to force your progress.

How empowering.

In the end, though, Mega Man 8 falls down simply because it isn’t any fun. It doesn’t lean into its camp value, and indeed seems utterly unaware**** of it. It’s a game that doesn’t seem to care whether or not you play it, and certainly doesn’t go out of its way to help you like it. It’s a game whose few innovations are halfhearted and misguided, and which didn’t convince anyone — including Capcom — that the series had much reason to continue.

Mega Man 8 was ported the next year to the ill-fated Sega Saturn — with some different music and nostalgic visits from Cut Man and Wood Man — making it the first multiplatform Mega Man game…but that was it for the numbered games. Mega Man & Bass, one more classic-style platformer, was released in 1998 for the Super Famicom in Japan only. It wouldn’t be localized until 2002 — as a port to the Gameboy Advance — so small was the demand for another entry in the series. Reports are that it sold well, but evidently not well enough for Capcom to invest resources in another sequel.

The classic series was essentially dead. Mega Man X was still going strong — 1997 would see the first PlayStation installment with Mega Man X4, a game that did far better at demonstrating the ability of its own series to survive another generation — but the eternal clash between Doctors Light and Wily was brought to an unceremonious, unmourned non-conclusion.

Once Capcom’s cash cow, Mega Man was quietly retired. Yesterday’s hero saw the world move on without him. And the children and gamers that grew up with him, loving him, helping him…probably didn’t even realize he was gone.

Mega Man 8 sure didn’t give anyone much reason to miss him.

Best Robot Master: Sword Man

Best Stage: Sword Man

Best Weapon: Flame Sword

Best Theme: Tengu Man

Overall Ranking: 2 > 7 > 5 > 4 > 3 > 1 > 6 > 8

(All screenshots courtesy of this wonderful man.)

—–

* I do wonder now if it’s theoretically possible here, thanks to the inclusion of the Mega Ball. I’ll never, ever attempt such a horrific undertaking, but I am curious.

** Not strictly true, as I’ve heard that the Ice Wave can also deal minimal damage, but that’s clearly not a feasible way to fight the boss, and I’m not sure there’s enough ammunition to kill it.

*** Online sources don’t seem to agree on what these transformations are called. I’m using the names from the original manual. I assume part of the reason for the confusion is that the items are never named in the game. I also assume that many players don’t even know they’ve collected Rush upgrades, as they aren’t told and would have to accidentally notice that they’ve been added to the inventory screen.

**** Much like Resident Evil, which was similarly unaware of its own silliness, but which made up for it in spades with incredible atmosphere and genuine scares.