We ended last week on a riveting cliffhanger: would ALF really devote an entire second episode to showing clips of itself?

Well, breathe easy, dear reader. The answer is yes!

Of course, we can’t hold this against “Tonight, Tonight.” As I mentioned in the last review, this originally aired as a one-hour special. While one hour of continuous ALF clips sounds very much like my own personal hell, it’s not quite as self-indulgent as airing two half-hours of clips on back to back weeks. We also can’t hold it against “Tonight, Tonight” that this particular clip show opens with a recap of last week’s clip show. As fucking bizarre as that is, it’s a quirk of breaking it into time-slot friendly chunks for syndication. I’ll save my venom for the stuff the show actually does wrong, rather than the wrong that gets done to it down the line.

After a reprise of last week’s telephone chat with Johnny Carson, ALF attempts to console the legendary talk show host by offering to spend a night in a hot tub with him. So…that happens. (And I have a revised vision of my own personal hell.)

Again, we don’t hear Carson’s voice, which is fully expected in one way (God knows he was well above this shit), and yet really strange in another…but that observation won’t make sense until later, so I’ll get to it then.

Anyway, Ed McMahon’s first line in the episode is “You’re in big trouble, mister,” because he mistakenly believed he agreed to guest star in that show starring the more famous Tanners. ALF tells him to go fuck himself and then shows five full minutes of clips. Wow, we really blasted right through the episode, didn’t we?

This string of clips includes one I’ve never seen before. It’s obviously an outtake, because Brian is smiling, but other than that I have no idea what I’m looking at.

ALF pulls on a rope or something while Kate screams at him to stop. He doesn’t, which is hilarious to the recorded sounds of laughing dead people. Then some plaster falls on the table while she holds her son close, resigning herself to the fact that every one of them will die in this house.

I have no idea what episode that clip is from. When I reviewed season one I was stuck using syndication edits, but since then the episodes have been uncut. Maybe it’s something that was trimmed from a season one episode, or maybe it’s yet another case of an ALF clip show “reminding” us of something that hasn’t even aired yet. Guess where I’m laying my bet.

Then we’re back on the set of The Tonight Show, and ALF says he needs to go somewhere. He asks Ed to take over hosting duties, but thinks better of it when he realizes that he can just show clips of himself instead. That way nobody has to stand around asking, “Where’s Poochie?”

There’s a theme to this set of clips, too. “ALF leaving the room.”

No, I’m not joking. We really do get a string of clips that show ALF traveling from one room to the other.

Close your eyes, take a deep breath, and then answer honestly: did this shit really need to be one hour?

We come back, but ALF isn’t there. Fred De Cordova takes a seat so that he can respect sitcom blocking limitations and asks where ALF went.

“Who cares?” Ed McMahon replies. “At least he’s gone.”

Man, who would have guessed Ed McMahon would turn out to be my soul mate?

Fred’s raising a valid question, but it’s not the question I’m raising. See, I’d prefer to know why the fuck this is still airing. In their universe, The Tonight Show seems to be treated like a live program. I’m willing to accept that as an explanation of why ALF manages to get away with a bit more than he should.

I’m not, however, willing to accept that as an explanation of why they let him go apeshit on their stage for a solid hour in front of a national audience.

I know it’s not good form to interrupt live programming and replace it with something else. You really shouldn’t do it unless there’s some kind of exceptional reason to, but I guess I’m old fashioned because I’d consider a space alien wrecking up the place to fit that definition just fine.

Fred De Cordova shouldn’t be asking where ALF went. He should already have shut down production, and viewers at home should be halfway into a classic Carson rerun.

The number one rule of live television isn’t “don’t stop.” That might be rule number two. Rule number one, however, is don’t, under any circumstances, broadcast a live waste of everybody’s time.

You either need to admit defeat and abandon The Tonight Show with Gordon Shumway, or you need to stab ALF in the brain with a screwdriver and let Ed McMahon take over for the duration.

Anyway, we find out where ALF is and…

I don’t know what this is.

I don’t.

I have no motherfucking clue what the motherfuck I’m looking at.

I’m broken. ALF broke me. I’ve lost all faith in humanity and want to cry.

I assume this is some kind of stolen Carson bit. I’m also assuming, like “Melmac the Magnificent,” there’s no twist given to the original material at all. Paul Fusco must have a motivational poster on his wall that reads IMITATION IS THE HIGHEST FORM OF PUPPETRY.

I’m assuming there’s no twist because nothing in this sequence has anything to do with ALF, ALF, Melmac, or anything else specific to the character. And I’m assuming it’s a pre-existing Carson bit because ALF does a very obvious vocal impression of him while he sells vitamins or who the fuck fucking fuck fuck.

There is an attractive blonde (the screen grab doesn’t do her justice, I promise) who gets to stand there while ALF insults her repeatedly until the skit ends, at which point she’s required to rub him while he quivers with sexual excitement. It’s quality television.

I don’t have any idea who this woman is, but for fuck’s sake almighty she earned her paycheck.

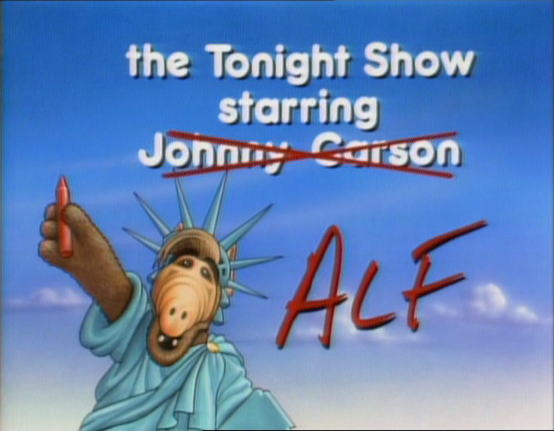

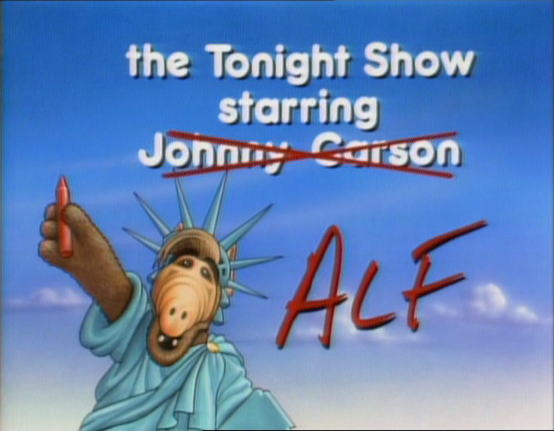

Then we get a commercial break, with one of those illustrated title cards. It’s ALF as the Statue of Liberty, reminding you that there is no God. It’s also a near-exact copy of a title card from the previous episode, and a near-exact reprise of the Mt. Rushmore gag we see in a clip from “Hail to the Chief.” Even by clip show standards, this is some lazy-ass bullshit.

Back in host-mode, ALF calls Ed McMahon “Edipus.” That’s sure to lead to some interesting explanations from the parents of the kids watching at home.

Then he introduces another set of clips and…well, I’ve got to be honest: I like them.

No, I do. I mean it.

They’re clips of ALF reciting a bunch of my Melmac Facts, and that actually works.

See, Melmac lore* is far from important to the show, but it adds a lot of flavor. New viewers may enjoy having this unfamiliar culture fleshed out for them, and current fans may enjoy the reminders of all the little details they’ve forgotten. It’s a condensed history of a civilization that makes up a huge, largely-unspoken part of ALF’s background…and which we’ve never seen, outside of a single scene in “Help Me, Rhonda.”

This is one of the very, very few things that actually deserves to be recapped. What’s more…they’re actually funny. Unlike most clips — which are obviously carved from a larger storyline and therefore feel out of place — these work perfectly well in isolation. They’re setup and punchline in one, not weighed down by their original contexts in the show and perfectly suited to being parceled out.

In one of the clips, ALF says, “On Melmac, some guy called me a snitch just because I turned him in to the Secret Police.” That’s a damned solid line, and it doesn’t matter what episode it comes from.**

By no means am I arguing that ALF needed a clip show, but I will say that as long as ALF is doing a clip show, this is exactly the sort of thing it should contain. Especially when the alternative is clips of ALF falling off of things and burping.

Shockingly, this perfectly-good series of clips is followed by the framing story’s first legitimately funny moment.

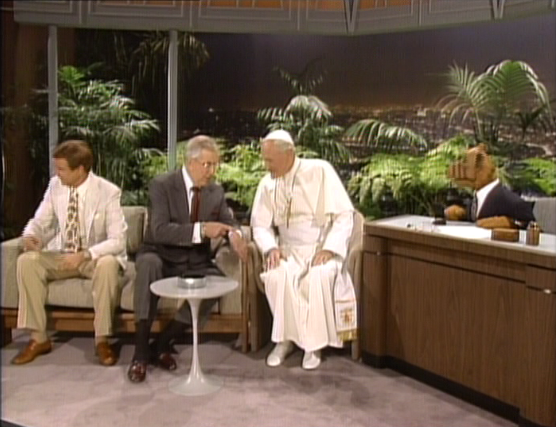

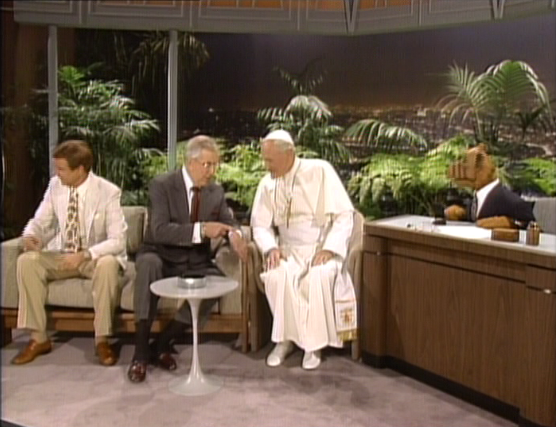

Ed McMahon informs ALF that their next guest, Pope John Paul II, is waiting backstage. ALF says, “Great! Let’s bring him out!”

To the strains of Ave Maria, the curtains part to reveal His Holiness.

At which point ALF says, “…right after I play these clips,” and the curtain falls right back in the pope’s face.

It’s an easy visual gag, but it’s perfectly timed. It works because it has exactly the right rhythm. It’s also a great, absurd way to parody the conventions of the talk show format…which is what a better sitcom would have been doing all along, rather than having its lead character buy right into it with no interesting spin whatsoever.

A moment like this belongs…well, it belongs in a comedy. What does it say about “Tonight, Tonight” that this qualifies as an exception? Well, it says what it’s been saying all along: this isn’t a comedy. It’s Paul Fusco’s late night pitch package.

Very strangely, this selection of clips includes one of ALF murdering Willie’s uncle. Is that really something that needs to be spotlighted? Is causing the death of a nice old man truly one of ALF’s most beloved moments?

How strange.

Rich Little*** then shows up on the set of The Tonight Show because Carson called him and asked him to go take over from ALF. I’m sure glad Johnny gave a shit about the fact that they’re broadcasting this trainwreck live, because nobody else working on it seemed to.

But, of course, Rich doesn’t take over. He just shows off his Johnny Carson impression for a few lines and steps back so ALF can have the spotlight again.

…and this is why I’m confused by the fact that we didn’t hear Johnny on the phone earlier. If you’ve already paid Rich Little — and he’s already doing that impression in your episode — why not have him actually play Johnny in that conversation?

It’s weird that we have ALF doing a Carson impression, and then Little doing a Carson impression, but when Carson himself calls nobody is doing a Carson impression.

Maybe having Little-as-Little on the show instead of Little-as-Carson could have worked, but not just to trot him out and forget about him.

Perhaps Little could have done his Carson impression, just as he does here, followed immediately by ALF telling him that his impression sucks dick. Then the two of them could start competitively impersonating Johnny…kind of like Steve Coogan and Rob Bryden with their Michael Caine impressions in The Trip.****

But that would require Paul Fusco having to share the spotlight, and God fuckin’ forbid. Instead Little gets a few seconds to do his thing, and then we’re back to clips.

Jesus.

We get our final title card (mercy of small mercies), and then ALF says, “Let’s put it to a vote. Was this the best Tonight Show ever?”

The audience, of course, applauds wildly. See that, network executives? ALL THIS COULD BE YOURS

And that’s pretty much the end of the show. This half was far more clip-heavy than the first, which makes it feel lazier but also makes it a hell of a lot more watchable.

A friend pointed out to me last week that Fusco’s egotism is in overdrive here and, necessarily, in the “We Are Family” Late Night scene. After all, he doesn’t just make ALF the guest on a talk show — which certainly would have made a lot more sense in either context — he makes him the host. ALF isn’t just popular enough to be featured on great shows…in Fusco’s mind, ALF should be the great show. Not because he earned it, but because he’s ALF.

To Fusco, ALF is already “bigger” than his own show. He appears here not in a fantasy sequence or a dream or anything like that…he’s just ALF, the real-world celebrity. Notice who hasn’t been invited to this networking luncheon? That’s right…literally anybody else from the show ALF. By no means is ALF in this together with the Tanners. The moment he, and Fusco, can shed them, they will be shed.

ALF is a prefabricated icon, designed to be plugged into everything imaginable. That lousy sitcom that bears his name? That’s just one thing of many that he does…or will do. He’s destined for bigger things…not like those limited supporting players Max Wright, Anne Schedeen, Benji Gregory, or Andrea Elson. They should be glad to spend 80 hours a week in danger of breaking their spines for the honor of filming a show with him. They should be thanking him.

It says a lot that only ALF invites only himself to this hour-long celebration of ALF. The other actors could all have been killed in a bus accident (on their way, no doubt, to film on-location in the desert for “ALF’s Passable Passover”) and neither ALF nor Fusco would have been any worse for the loss. They were designed to be disposable.

In the comments for last week’s review, Casey reminded us that Kermit the Frog once hosted The Tonight Show. He was kind enough to leave a link, which I encourage you to click, but I confess I didn’t have the time to watch it between then and now.

I will, however, make a very confident assumption: it was a lot better than this.

Jim Henson was a skilled improvisor. He had to be; he worked with children an awful lot on Sesame Street. No matter how much you rehearse or write in advance, something is going to turn out differently than expected. Henson learned over the course of a long (but still far too short) career how to handle situations as they arose, and I can very easily see him making Kermit a fitting enough host for The Tonight Show.

Also worth noting, though, is that Henson was invited to perform Kermit as the host of that show. That, too, was the result of a career built on talent. Talent for comedy, talent for puppetry, talent for characterization. He advanced step by step through the entertainment world not because he forced it, but because there were people at every landing that recognized his talent and helped him forward.

Compare this, again, to the prefabricated nature of ALF. Kermit was invited to host The Tonight Show because The Tonight Show wanted him there; ALF was foisted upon The Tonight Show because Paul Fusco wanted him there.

But perhaps the most important difference is this: Kermit is a Muppet. ALF was just ALF. This meant that Kermit wasn’t some one-off oddity; he came with an entire world and culture behind him. And that world was populated by other Henson characters, as well as the characters of other performers. Kermit may well be the most famous Muppet, but if you ask 100 people about their favorite Muppet memories, you’re going to hear a lot about Miss Piggy, Fozzie Bear, Gonzo, Cookie Monster, Bert and Ernie, Big Bird, Scooter, Oscar, Grover, Bunsen and Beaker, Rowlf, Statler and Waldorf…the list goes on.

Henson never wanted to be a celebrity as much as he wanted an outlet for his creativity. He wanted to experiment. He wanted to test his own boundaries. Sometimes, to be totally honest, he failed. But let me be totally honest once more when I say that that doesn’t matter. Henson is — and surely will be for a long time — loved, revered, and remembered. He was by all accounts a great man who cared about the work he did and inspired more lives and careers than we could ever hope to count. He didn’t want to rocket himself to stardom and spit on the people below; he wanted to take everyone along with him.

You know that scene at the end of The Muppet Movie? The one where they reprise “The Rainbow Connection” and we see a massive throng of Muppets crammed together, performing it? That was Henson’s idea of heaven. Everyone was there. Nobody was more important than anybody else. Everybody had something to be thankful for.

By contrast, you know those scenes that I recapped this week and last? The ones where ALF is the star and he gets off on bossing people around and pissing them off? That was Fusco’s idea of heaven.

I’ll end with one more very illustrative (in my humble opinion) difference between Fusco and Henson.

As I’ve mentioned before, Paul Fusco never wanted anyone to see ALF as a character, or a puppet. ALF was ALF. This caused Tina Fey no end of logistical headaches as a minor ALF appearance on the NBC Anniversary Special meant investing far too much planning in ways to get ALF into shot without anyone seeing that he wasn’t real. It also explains why in all of the ALF outtakes I’ve seen (yes, even the racially charged diatribes), Fusco stays in character as ALF; he doesn’t talk to his costars between takes, he talks to them through the puppet. Because ALF is real.

A few years ago, I read The Wisdom of Big Bird, which is an absolutely lovely little book by Caroll Spinney, who played and still plays that Muppet. He relayed a story that, at the time, struck me the same way it seemed to strike Caroll. I have to paraphrase, so I apologize for any details that I get wrong, but Caroll and Jim Henson were together in an office, talking about some issue or another on Sesame Street. Henson got up to get something, and in doing so he kicked the Ernie puppet out of the way. Caroll was aghast. Reading it, I was too. Caroll said, “You kicked Ernie.” And Jim Henson, flatly, said, “Caroll. It’s a puppet.”

Only now, seeing that as the polar opposite of Fusco’s attitude, does it make sense to me. Henson wasn’t being disrespectful to his creation. To us, yes, Ernie is a character, but to him, it’s a puppet. At least, it’s a puppet until he’s giving it life.

Ernie had no inherent right to popularity or success. He was a creation of felt, staples, and cloth. Whatever audiences saw in him (which was a lot, as evidenced by Caroll’s reaction to seeing him get kicked around) was not innate; it had to be brought about through hard work on Henson’s part.

In other words, Henson knew he had to earn everything. Ernie didn’t have to, Kermit didn’t have to, Guy Smiley didn’t have to. But Jim Henson had to. And the more he let himself remain aware of the fact that the puppets were nothing without his gift of life, the more invested he became in working hard to develop them, and to make them the enduring characters they still are today.

ALF didn’t endure. And ALF couldn’t endure. Because, as far as Paul Fusco was concerned, he was fine on his own.

There was no reason to work at it; ALF had a bright future ahead of him. It was just a question of getting him out there and letting it happen.

We all see where that got him.

—–

* No relation to Adam.

** “Hit Me With Your Best Shot,” though…just in case you were in danger of losing sleep.

*** I was curious about whether or not Rich Little was still alive. It turns out he is. In researching that fact, though, I discovered Rich Little’s Christmas Carol. Forty five seconds of that garbage was enough to make me feel seasonal depression all over again. Look it up if you must…but know this: it’s so bad, even I am not cruel enough to include it in next year’s Xmas stream.

**** Or the same pair with their Al Pacino impressions in Tristram Shandy. Both are highlights of their respective films.

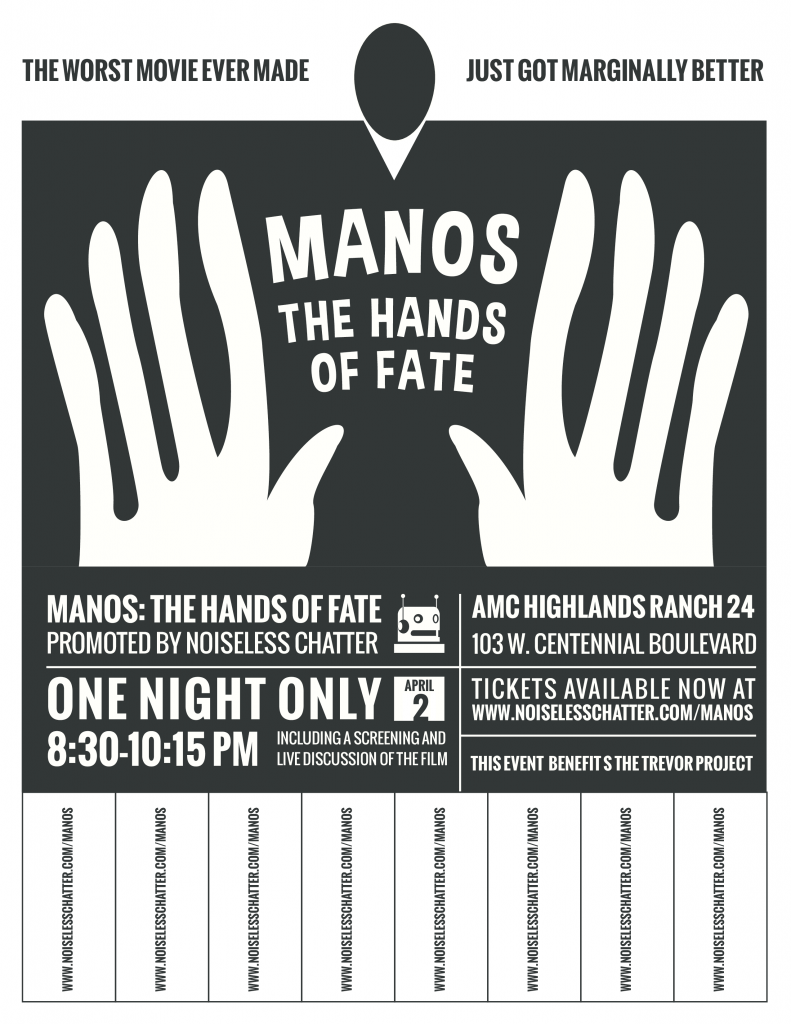

The live screening of the remastered / restored “Manos” The Hands of Fate is happening April 2, and you’re invited. All proceeds benefit The Trevor Project, and you’ll get to enjoy a great night out with a terrible movie and excellent conversation. Tickets are on sale as of today…and a few have already been sold! We need to sell quite a few more, though, in order for AMC to host the event.

The live screening of the remastered / restored “Manos” The Hands of Fate is happening April 2, and you’re invited. All proceeds benefit The Trevor Project, and you’ll get to enjoy a great night out with a terrible movie and excellent conversation. Tickets are on sale as of today…and a few have already been sold! We need to sell quite a few more, though, in order for AMC to host the event.