The following is a great article on artistic discussions of the deep web, online privacy, social responsibility, and more, courtesy of UK-based reader Patrick Massey. I found this fascinating, worrying, and enlightening in equal parts, and I hope you experience some mix of those three things as well. Take it away, Patrick.

A “Marco Polo” of the contemporary public sphere: “Internet” and “privacy.” The two phenomena are often yoked together in the news: the various problems of data access (who should be denied it? Whose data should be sacrosanct? What justifies access sub rosa?) swap pre-eminence in public consciousness as the Big Three of ‘net privacy–Snowden, Assange, Manning–swap the limelight. (In this essay, “‘net” refers to both the readily accessible surface Web, typically but carelessly referred to as “the Internet,” hence my coining an alternative term— and the Deep Web, the Internet’s large, largely criminal underbelly.)

In this essay, I want to consider how, not the news, but contemporary visual culture (i.e. screen and theatre of 2013/4) visualizes and/or fails to visualize ‘net privacy. I hope to address familiar issues of ‘net privacy via less familiar co-ordinates. Of course, William Gibson and other genre authors have been addressing cyber-issues, crafting cyber-aesthetics for years; but here I’m thinking of a) the real world ‘net in b) mainstream works of c) the last two years.

SCREEN MEDIA, and The ‘Net/Screen Problem

Documentaries aside (though cf. Terms and Conditions May Apply, Citizen Four), Internet privacy is surprisingly scantly treated in ‘13/4 screen culture. The two so bracketed, ‘net-oriented films I remember most readily–Her and Transcendence–privilege online addiction and a deus ex machina Johnny Depp over issues of ‘net privacy. Even Assange bio The Fifth Estate is more reportage, a primer on its subject and Wikileaks, than a meditation on abstractions or themes (and even then, Assange’s relationship to the media is privileged over ‘net privacy).

In mainstream C21 cinema in sum, ‘net privacy is principally a means to emotive ends. In Hard Candy, Chatroom, and Trust, the abuse of ‘net privacy does not itself merit attention–rather, it enables plot-wise the kidnaps et al that define and rather pre-occupy those thrillers. Even in the Catfish franchise [’10 film + current MTV series], any interrogation of ‘net privacy abuse is suborned to affect: to first terror (“who are these people?”), then horror (“look at those people!”). Although Catfish et al can be, indeed have been starting-points for discussing ‘net privacy, that discussion doesn’t happen in the films themselves.

Such scanty treatment of ‘net privacy on screen owes not only, I think, to auteurs’ simply “not having got round to it”, but also to a fundamental, broader disjunction between the ‘net and screen media. The ‘net does not readily lend itself to concrete visualization. One must get figurative, experimental; but screen media tend towards “meatspatial” settings— realities, however fantastical or futuristic. Consider Star Trek’s holodeck: always a real-world milieu, often Earth-historical, never a Tron-scape. Consider too the recent backdoor pilot for CSI Cyber: introducing a series oriented around the Deep Web, yet resorting latterly to “Female (Early 20s)” showing hard copy evidence of her online chat-room ignominy to meatspatial paparazzi in a meatspatial VEGAS: EXT.

I might suggest three reasons for this disjunction. First, the chokehold of corporate network funding and the likelier non-profitability of experimentalism [versus the realism that characterizes the “New Golden Age” of television]; the desire to fully exploit and justify investment in physical sets; and third (and still more tentatively proffered), the Internet’s being TV and film’s unheimlich, uncanny counterpart, perhaps frustrating the interrogation of the former by the latter… Heady stuff. But the bottom line for us is: if the Internet in sum cannot find a screen aesthetic, what hope for its clandestine, its even less readily visualized cyberspaces? And what hope consequently for addressing ‘net privacy?

Happily, ‘net privacy has been better visualized in theatre of ‘13/4— a medium naturally more amenable to the figurative and the experimental.

THEATRE, and Romancing the ‘Net

In The Net Effect, Thomas Streeter posits romanticism as a key co-ordinate in ‘net studies. He primarily argues that neoliberal forces propagate a romantic individualist idea of computing, and that “capital R” Romanticism can help us understand the social meaning of computers.

With this precedent in mind, I turn to ‘net privacy in theatre of ‘13/4. All the plays I’m going to consider deal with perversions, criminal iterations of ‘net privacy. But none less than Keats was ‘half in love with death’; and however perverse their content gets, these plays evince, if not a Romantic aesthetic per se, then something sufficiently akin that I’m going to draw formal Romantic parallels and beg your indulgence.

Jen Haley’s The Nether deals with online pederasty in a private “Hideaway” [Haley’s device]. In fashioning the Hideaway, Haley eschews a complementarily grimy, abject aesthetic for irony: it is an archetypal country estate, with trees, gazebo, and fishing-pond. Notwithstanding its nominally Victorian context, a Romantic aesthetic— Blakeian innocence, a “Lakeland Poetic” idealizing of Nature— surely underpins a milieu that presents like this:

Blakeian also is Iris, the Hideaway’s resident, white-clad sprite–and “willing” victim of virtual child abuse. Innocent prima facie, but horribly au fait with abhorrent experience (“Perhaps you’d like to use the axe first”): Iris embodies the disjunction that hinges Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience. Note finally how, according to its creator, “it’d upset a balance” in the Hideaway to suggest that Iris could grow older: anyone whose mind went to the Romantic organic conception of nature, give yourself a mark.

Price’s Teh [sic] Internet is Serious Business is a reportage piece about the respective rise and fall of the “hacktivist” groups Anonymous and LulzSec. Its dominant aesthetic is anarchic: a ball pit abuts the stage, from and around which emerge Socially Awkward Penguin and other costumed memes. Bright lights, Harlem Shake: you get the drift. At first sight, privacy is not the word here. But Price also depicts hackers’ private forums— and here, the staging tends towards lyricism. Computer code is recited as poetry (cf. Chandra’s recent equivalence of the two, if intrigued); databyte flow, enacted as dance. Here, literarily and physically, is a lyricism where elsewhere is jouissance: thus is privacy “Romanticized” (cf. Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads, Whitman’s “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” Dvorak’s New World Symphony…).

James Graham’s Privacy tacks otherwise to Haley and Price. Graham’s is a synoptic approach to ‘net privacy, a condemnation of illiberal governmental/corporate/ security state malpractice as regards ostensibly password-protected public data. Such factuality is not the Romantic way, likewise Privacy’s format: a hybrid of verbatim enactments of his [The Writer’s] interviews with real British Establishment figures (Shami Chakrabarti, anyone? Well, Google her sometime); lectures; and fourth-wall—breaking audience participation. For good measure, Privacy rides roughshod over the Romantic exaltation of the subject: an array of thumbprints is the default [screen] backdrop, and the “subject” of the audience participation (having given prior permission) has her real-world online footprint, herself by proxy dissected onstage.

Despite all this, Privacy retains a double pertinence. First, it acts as a counter-proof: as its core is non-Romantic, so Privacy does not depict privacy itself [cf. Haley’s Hideaway, Price’s hackers’ forums] but exposes, is an exposé of its absence. Second, its aesthetic rather taps into the “other end” of Romanticism, where rapturous apostrophes fade into disquiet, into sublimity: the awesome dimensions of Big Data, the staging [that screen, those magnified thumbprints] vis-à-vis the actors and the script’s analytical impulse.

So: 2 1/2 proofs and a counter-proof, we might say, of a relationship between ‘net privacy and a quasi-Romantic aesthetic. My humble explanation: that the ‘net (especially the Deep Web) remains so broadly un-comprehended, its depth so untapped, as to inspire from us what “the naked countenance of Earth” [Shelley] inspired from the Romantics.

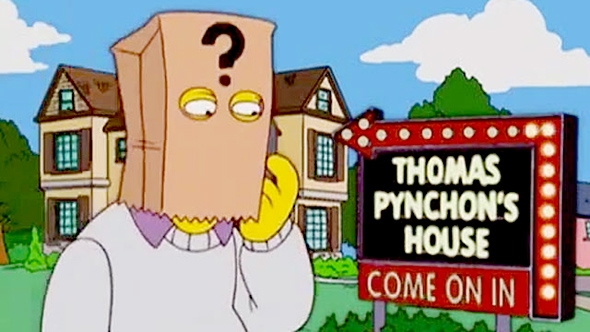

PYNCHON: A Quick Nota Bene

In another world, where space and time were as playthings, I’d fully discuss Thomas Pynchon’s Bleeding Edge: the only “literary” fictional novel that readily comes to mind that not only foreground ‘net privacy as a theme, but actually figures it as a distinct, visualized cyberspace–DeepArcher; conceived of as a ‘grand-scale motel for the afflicted’, for Pynchon’s kindred preterite [cf. Gravity’s Rainbow, or Google judiciously]; variously iterated as train concourse, desert, and galactic Void; and ultimately a Purgatory for leads, lovers, and 9/11 victims all encountered (and killed off) in the narrative. (On a complementary note for that latter point: Kabbalistic imagery and lexis is deployed in descriptions of the Void). Would I could share my MA dissertation with you all; but I’ll highlight simply this: doing what even screen media cannot (at least easily), and in keeping with his typical trickster mode, Pynchon visualizes ‘net privacy chimerically; that one cannot identify a definitive DA-scape is the whole point. A nicely postmodern note, I hope, on which to finish considering contemporary cultural visualizations of the ‘net.