Neither Bob Dylan nor John Lennon survived 1980. And yet, they’re both still with us. Transformed…echoes of the past. One solid, one ethereal…but both of them spokesmen for a time long gone. The major difference, of course, is that only Dylan’s career was buried. It was Lennon’s body.

Tragedy is relative. In somebody’s mind, John Lennon deserved to die. His death, for reasons neither you nor I nor anybody will ever understand, was necessary. We may not have the right as individuals to decide who should live and who should die, but we all have the ability. One finger, one firearm, one bullet. It’s all anybody needs. It happens all the time. It’s usually somebody we don’t know. It’s sometimes a man who changed the world.

That early December gunshot can still be heard, if you listen hard enough. If you concentrate. If you take a moment to think about how the entire world shifted from one state of being to another, from one bright future to an uncertain, poorer, infinitely more frightening one. It’s easy to hear it, when you think like that. It’s easy to hear it still pounding against your eardrums…a violent swing into another time and place…an audible reduction of hope and optimism. A tragedy in New York City that left the world lost and confused. It’s not that hard to imagine now.

That early December gunshot can still be heard, if you listen hard enough. If you concentrate. If you take a moment to think about how the entire world shifted from one state of being to another, from one bright future to an uncertain, poorer, infinitely more frightening one. It’s easy to hear it, when you think like that. It’s easy to hear it still pounding against your eardrums…a violent swing into another time and place…an audible reduction of hope and optimism. A tragedy in New York City that left the world lost and confused. It’s not that hard to imagine now.

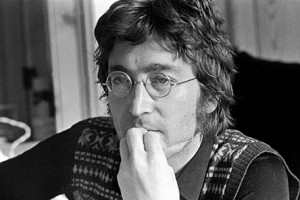

John Lennon was a cultural icon…one of very few people — and even fewer musicians — who shaped the planet on which he lived. He was also — and this is a bit harder to imagine — a human being. He’s dead now, though there’s no reason he has to be. He’s dead now because that’s what somebody decided he’d be.

That was almost thirty-two years ago, as of this writing. I’m thirty-one. I never shared the world that John Lennon helped shape. By the time I was born he was already gone. I inherited a world that was already missing him. I can still hear the echo.

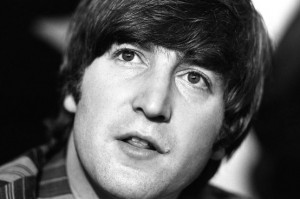

Bob Dylan shared a world with John Lennon. And a friendship. And a history. John Lennon and The Beatles changed history, but Bob Dylan changed The Beatles. He broadened their horizons…an intellectual and experimental emissary from America. They became close. They even wrote a song together, though it was never recorded. Dylan spent most of his time with George Harrison, with whom he wrote songs that actually were recorded. For years John and Bob traded barbs in their separate recordings. They were friendly adversaries. They were troubadours pulling us toward a brighter future. They redefined music, and it was up to everybody else to follow along, and behind.

We all, to some extent, lost John Lennon, but a few people lost him in a more substantial way than they can ever articulate.

We all, to some extent, lost John Lennon, but a few people lost him in a more substantial way than they can ever articulate.

Now, thirty-two years and fifteen albums later, Dylan closes Tempest with a paean to his lost friend, the circling, haunting “Roll On John.”

I had never wondered before what Bob Dylan must have thought on the night of December 20, 1980. Why would I have? Yet also…why wouldn’t I have?

It’s all too easy to see celebrities as superhuman. The larger they loom, the further detached they are from the world we inhabit. Particularly in the case of figures so massive as John Lennon and Bob Dylan. They don’t appear to us as people, but as presences. As messengers from magical kingdoms we would not be fit to enter. They aren’t real…they are forces beyond our understanding.

And yet…

And yet.

They can be killed. They can be revealed as mortals after all. At which point…it’s too late.

Bob Dylan lost his friend. We may have lost an idol, a hero, a figurehead, but somewhere out there…somewhere, on a cold winter’s night, a confused artist lost a man he loved.

Bob Dylan lost his friend. We may have lost an idol, a hero, a figurehead, but somewhere out there…somewhere, on a cold winter’s night, a confused artist lost a man he loved.

“Roll On John” swims in survivor’s guilt. Bob Dylan is an old man…something John Lennon was fated never to be.

On the last night of his life, though, if anyone would have expected one of them to be around in 2012, it would have been Lennon. Earlier that year, Lennon released Double Fantasy. It met with a fairly universal critical shrug, but went on to win the Grammy for album of the year, and has received retroactive reappraisal elevating some of its tracks to Lennon’s canon of all-time best, such as “(Just Like) Starting Over,” “Woman,” and the disarmingly poignant “Watching the Wheels.” Whether he was recording the best music of his career is, was, and must always be up for debate, but there’s no question that he had a great deal left to say, and a still-powerful voice with which to say it.

By contrast, Dylan was a universal joke. An aimless and meandering has-been who was currently in the depths of an embarrassingly public conversion to Christianity. The dangerous Jewish folk-singer who once led millions to challenge the status quo was now unironically and uncreatively singing the praises of Jesus on albums that couldn’t be forgotten soon enough. He had just released Saved, his second disposable album of love songs to Christ (of three). It featured songs such as “Solid Rock,” “Covenant Woman” and “Saving Grace,” all of which were used as ammunition against him by critics and fans alike. He was unquestionably recording the worst music of his career, and it was taken as gospel — ahem — that had nothing left to say, and a failing voice that wouldn’t stop saying it.

It was a stumble Dylan wouldn’t recover from for at least nine years (if your personal resurgence point is Oh! Mercy) and maybe as long as seventeen years (if you’d prefer to go with Time Out of Mind). In 1980, there was no coming back. Dylan was written off. He was dead.

It was a stumble Dylan wouldn’t recover from for at least nine years (if your personal resurgence point is Oh! Mercy) and maybe as long as seventeen years (if you’d prefer to go with Time Out of Mind). In 1980, there was no coming back. Dylan was written off. He was dead.

Before the year ended, Lennon joined him. He was dead, too.

Lennon, with a rich and unknowable future before him, was gone. Is gone. Dylan, lost within himself and fumbling to recapture his lost talent, was still alive. Is still alive. I’m not sure that anyone’s pondered the justice of that. Anyone apart from Dylan, that is. Of course.

“I read the news today, oh boy,” Dylan sings in “Roll On John.” Just one of many Lennon lyrics and references that take on a bone-chilling resonance in this new context. This new context of an old man who outlived his usefulness mourning the loss of a young man who never got the chance to fulfill his.

Dylan howls and growls with a voice from beyond the grave…a tormented spirit raging to unburden himself of earthly woe, but to no avail. Bob Dylan started his career by impersonating Woody Guthrie, but seems sometimes to be auditioning now for the part of Jacob Marley.

Lennon’s death was a chance for Dylan — like everybody else — to look inward. If his musical output that followed is any indication, it’s not an opportunity he took seriously. But now, with so many decades separating him from the tragedy, he has the chance to look backward. In fact, “Roll On John” is adapted from a song of the same title Dylan was performing as far back as 1961. As an old man Dylan reflects on a decades-old tragedy, and sees in that reflection himself as a young man, singing a song that wouldn’t yet have meaning for him…wouldn’t yet have meaning until one of his contemporaries, a gentle, love-preaching genius, was shot in the back just before Christmas, and left for dead.

Lennon’s death was a chance for Dylan — like everybody else — to look inward. If his musical output that followed is any indication, it’s not an opportunity he took seriously. But now, with so many decades separating him from the tragedy, he has the chance to look backward. In fact, “Roll On John” is adapted from a song of the same title Dylan was performing as far back as 1961. As an old man Dylan reflects on a decades-old tragedy, and sees in that reflection himself as a young man, singing a song that wouldn’t yet have meaning for him…wouldn’t yet have meaning until one of his contemporaries, a gentle, love-preaching genius, was shot in the back just before Christmas, and left for dead.

Dylan’s been through his share of tragedies since then, and it’s unlikely that the release of Tempest on September 11 was coincidental. His lovingly tormented remembrance of Lennon is one flavor of New York tragedy…and Dylan knows there are others. In fact, “Roll On John” follows the title track, which is about the sinking of the RMS Titanic. There’s a third flavor. The link is deliberate.

Tragedy is always a term decided by scope, and scope is always personal. The world can change on December 20 or September 11 or April 14 or any other combination of month and day that the calendar will allow. It can change for the better, or it can change for the worst. Waking up one morning does not suggest that you will wake up the next, and it only takes one person to make that decision for you.

Dylan survived, and Dylan survives. His career has been buried and exhumed so many times that keeping the critics satisfied has become exhausting. Instead, Dylan just does what Dylan does…and, sure enough, the critics came around, and are glad he survives.

Dylan survived, and Dylan survives. His career has been buried and exhumed so many times that keeping the critics satisfied has become exhausting. Instead, Dylan just does what Dylan does…and, sure enough, the critics came around, and are glad he survives.

But Dylan wonders.

If he could have traded places…

…he wonders. How the world would be different. How much he’d be missed, if he was the one gunned down in the street that night instead, at that phase in his career.

What would it mean to people? What could it mean to people? Is it better to die in your prime, loved and beloved, or to age fast and gracelessly, shedding relevance and ticket sales, as the world deteriorates around you?

Which is tragic? What really matters? A sinking ship, a falling tower, a silenced activist. An old man dying alone. A cynical world that can only be shocked back to reality by a major and devastating change. What is tragic? What really matters?

We’re all human, and yet we’re all different. We all hear the same words, and yet process different meanings. We all see the same man, and yet are flooded with different emotions.

Tragedy is what tragedy is. It’s a lesson Dylan waited a long time to learn, apparently. He might still be learning it. We all should be. After all, we’re in this together.

Roll on, Bob.