Paul Fusco never wanted a TV show. He wanted a franchise.

I can’t say for certain, but I think I’d be more than satisfied if somebody took note of a character I created and asked me to produce a show based on it. Fusco, however, seems to have had his sights set quite a bit higher. Or, at least, broader.

ALF was a merchandising juggernaut. He was sold as a stuffed animal, a Halloween costume, a set of toys, various terrifying robots that tried to talk to you, and a lot more. He had his own cereal, ice cream pops, video games, and trading cards. He had storybooks and flimsy plastic records and was a hand puppet included with Burger King kids meals.

But that’s not all; characters that appeal to kids are understandably going to be milked for all they’re worth, and ALF was no exception. ALF was an exception in terms of how he attempted to take over not only store shelves, but the airwaves.

Most people know ALF from ALF. But that’s only part of the story. In addition to this live action sitcom, he also appeared in a cartoon spinoff called ALF: The Animated Series, and a spinoff of that called ALF Tales. (Woo-oo.) We’d also eventually get a movie. It was made for TV, but Fusco, to this day, expresses interest in a proper theatrical feature.

Evidence that ALF is meant to be less of a character than he is a brand goes all the way back to the first episode of this show. It was then that we met the other characters who populate this “universe.” Now, cruising through season three, we know almost nothing more about them than we did then.

Paul Fusco wasn’t interested in building that universe, let alone fleshing it out, because it was disposable. It wasn’t where ALF belonged; it was one place where ALF happened to be. One place, if Fusco got his way, among so many. Why don’t we know anything about Willie? Well, why would we? He’s just some guy ALF met, and ALF is going to be meeting so many people in so many other contexts that this one isn’t worth thinking much about.

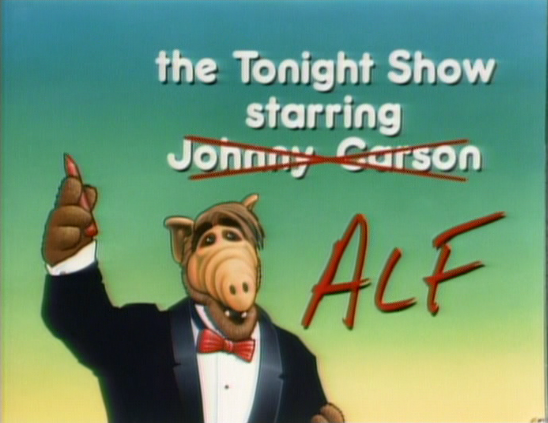

More specific evidence of Fusco’s multi-format aspirations can be found here, in this very episode. In it, ALF — some fucking how — is hosting The Tonight Show. Why? Who cares? Going from hiding from the Alien Task Force one week to hosting the most popular show on national television the next? Surely that’s nothing worth addressing.

You may remember that this isn’t the first time we see ALF acting as talk show host. “We Are Family” included a pointless (but, in retrospect, mercifully short) fantasy sequence of My Favorite Melmackian hosting Late Night. And, in real life, ALF would eventually host a talk show on TV Land called (optimistically) ALF’s Hit Talk Show. It ran for seven episodes and was then executed by firing squad.

ALF, as a brand, reeks of cold calculation. He isn’t being offered spinoffs; he’s being thrust into them. The more Fusco focuses on grooming the character for broader success, the less marketable he actually becomes. ALF ends up with a shelf life much shorter than he would have had, simply because there’s less in the way of development for anyone to remember him by.

I’m pretty confident in this. I’d wager that even though ALF had impressive viewing figures, relatively few people who watched it would remember today where the show was set. They wouldn’t remember the neighbors. They couldn’t name the Tanners. ALF is from Melmac and he eats cats. That’s all, and that’s all because his creator didn’t want to chain him down to one show.

We’ll talk more about this shortly, but, for now, just understand what you’re watching. It isn’t just a clip show (though it is, for fuck’s fucking fuck, a clip show)…it’s a pitch reel. Even as ALF is at the peak of its success, Fusco is looking to leave the rest of these losers behind.

Supporting characters? Not worth it. They’ll only slow you down.

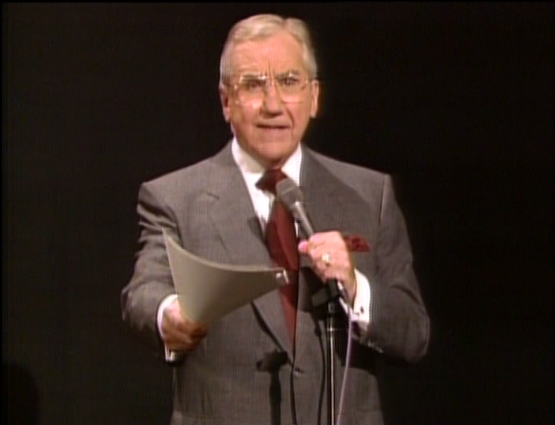

We get a Tonight Show intro that consists of a pretty straight narration from Ed McMahon, even introducing the band and Johnny Carson (who does not — SPOILER — appear in this heap of cat shit) before identifying ALF as the guest host. McMahon says all of this while some of ALF’s greatest moments glide by in the background, such as that time he wore a funny hat, and that other time he wore a funny hat. Then poor Ed McMahon has to reduce himself to saying “Heeeeeee-eeere’s ALF-ie!” and it can’t just be me who sees a little hope for death in his eyes.

McMahon would actually work again with ALF…on ALF’s Hit Talk Show. The more you dig into it, the more “Tonight, Tonight” feels like a back-door pilot.

Ask yourself this: Does “Tonight, Tonight” exist because it would make for a great episode of television? No. I mean…here it is and it fucking sucks. But even in terms of its intentions, what kid at the time was familiar with Johnny Carson? I certainly couldn’t stay up that late. Sure, I knew who he was, but that was about it. The specific routines and structure of his show were unknown to me, and I’d wager that that was the case for a large portion of ALF‘s viewing audience.

No, I think it’s far more likely that this episode exists because Fusco wanted to rub elbows with as many people as he could to make his dream of a cross-format ALF come true. It’s not a TV show; it’s a networking luncheon.

ALF comes out to a brassy, swing version of his own theme song which, I admit, is a pretty nice blend of both shows’ themes. It sounds fairly true to each of them, which is a nice surprise. He nods a bit to the audience…and then we get a full body shot! Yes!!

That means…

Wait. What the fuck is this? That’s not the midget. Where the shit is my midget?

Instead it’s just this…creepy ALF puppet on really thick legs. And Jesus Christ are those some beefy feet.

He looks terrible. Not that the midget’s costume ever looked good — it certainly didn’t, and that’s why I loved it — but whereas that looked silly, this looks horrifying. It looks like ALF ate some expired cheese and hasn’t gotten over the bloating.

It also moves in this really unnerving way, where only the upper half of his body does anything, so you see his mouth and head and arms working as normal, while his legs stay stock still. It’s like somebody nailed his feet to the stage.

ALF warms up the crowd with a killer opener: a joke about Michael Landon’s hair. That’s two Michael Landon jokes in three episodes. What can I say? These were…simpler times.

Then we see the studio audience pissing itself over the way this character hilariously said the name of a celebrity that they recognize.

And, well, if you ever wondered what the kinds of people who adored ALF looked like…here you go.

ALF quells the laughter of this riotous crowd of widows and pedophiles so that he can joke about what a shithole Burbank is. Ed McMahon laughs politely, secure in the knowledge that this does indeed qualify as overtime.

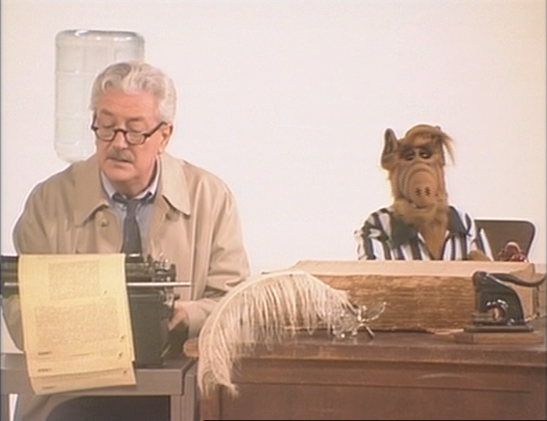

I wonder if much of this episode was actually filmed in front of the audience. It’s possible. As the boring as shit screengrabs this week betray, nothing happens in this episode. ALF sits behind a desk, which hides Fusco perfectly, and that’s about it. ALF’s Hit Talk Show was indeed filmed with a studio audience, and featured an almost identical setup to what we see here. It’s almost as though Paul Fusco was proving it could be done. Hmmmmm…

ALF then engages in some awkward banter with Tommy Newsom, Carson’s actual band leader. It’s brilliant material. Really top notch stuff. See, ALF jokes about Tommy wearing beige, exactly the kind of razor sharp material he’d be able to provide on a regular basis if he had his own talk show, hint hint.

Tommy has a rejoinder that hangs oddly in the air for much too long. It’s…weird. The audience laughs and so does ALF, who also compliments him on his return jab, so there isn’t supposed to be an awkward silence. And yet the editing is so loose and poor in this episode that it strands Newsom staring stage left, blinking, until they finally decide to cut away. It’s really strange, like some film student used this for their Intro to Editing project and NBC just slapped it on the air.

Anyway, ALF mimics Carson’s famous golf-swing gesture and we cut to commercial.

…wait. No we don’t. We cut to…

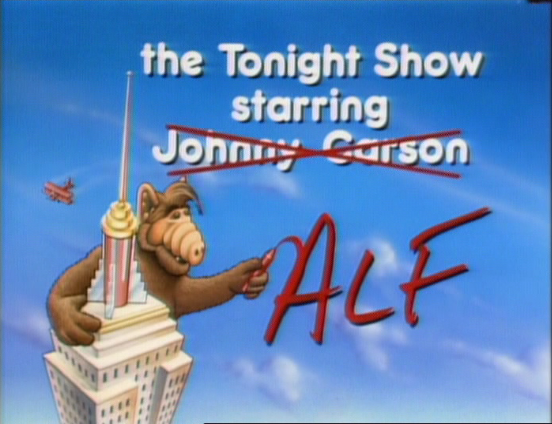

The hell? Another title sequence?

Come. The fuck. On.

I take back my earlier compliment about the Tonight Show / ALF theme song mashup. It’s only a good idea if you’re using it in place of the show’s usual intro. Using both that intro and the regular one is just a waste of the audience’s time.

What ridiculous padding…especially since both intros are just different ways of framing short clips of ALF reaction shots. Did we really need two vats of ALF clips dumped over our heads before THE EPISODE FULL OF ALF CLIPS even starts? I swear, “ALF’s Special Christmas” was fuck-awful, but “Tonight, Tonight” seems like it’s actually been bred in a lab to maximize audience disrespect.

Then we cut to commercial, and…

Oh sweet fuck my christ what is this.

That looks…god damn. I’m sorry. Just…god. Damn.

It would be okay — I guess — if this really was an ALF version of The Tonight Show. You know, an actual parody or something, or an April Fool’s episode of the late night talk show. Then these little touches would seem more appropriate and less embarrassingly self-indulgent. Instead, it’s the creator of ALF having ALF celebrate ALF on ALF while we watch ALF in clips from ALF.

It’s downright masturbatory, but at least this clip show is more forgivable than the one we had in the middle of season one (for fuck’s sake…). After all, again, at the time of “Tonight, Tonight” ALF was at the peak of its popularity. More people were tuning in, he was becoming more recognizable, and, in the pre-DVD age, these newcomers wouldn’t have had another way to experience any of the adventures that they’d missed.

But it’s not like ALF is so heavily serialized that new viewers would need to catch up on the story. Do we really need this? Granted, I’m railing more against clip shows in general here, but they’ve always bothered me. Wouldn’t new viewers rather see a half hour of new comedy than a shitty framing device and some out-of-context fragments from scenes that mean nothing to them?

Even when I was younger — well before DVDs — if I stumbled upon a show I wanted to watch and then saw that it was a clip show, I changed the channel. I just didn’t care. Far from serving as a comfortable point of entry — which I think was at least somewhat their intention — the clip show blocked me out. If I didn’t know who these people were, or why they were doing what they were doing, it was meaningless to me. Maybe some of the jokes would be funny…but then again, shouldn’t that be said of every episode?

I wonder how many current shows do them anymore. I do remember being very surprised when The Office (the American one, of course…) did one late in its life. What was the point? The show was successful because people could so easily view it. Netflix, iTunes, DVDs…all of these things spurred interest in a show that, at first, nobody seemed to be watching. Viewing figures increased in measurable waves because people were hearing good things, starting from the beginning, and catching up quickly. What, really, was the point of an Office clip show? To punish people looking for new content when they finally got around to watching it on the night it aired?

There is a fairly good joke that ALF gets here, greeting Ed by saying he hasn’t seen him since he opened his mail this morning. Again, not hilarious, but it’s the kind of thing that deserves a smile.

This of course being ALF and not something good like…um…Carson-era Tonight Show, the joke is belabored and over-explained until we drift out of the conversation and start daydreaming about murder.

Then there’s this exchange, which I’d comment upon, but I honestly think it’s far more illustrative to simply transcribe it. Ready? I’m not embellishing, editing, or altering in any way. This is exactly what gets said:

ED: Well, your show is certainly a hit, ALF.

ALF: What show is that, Ed?

ED: Well, ALF. Right here on NBC. 8 o’clock on Monday nights.

ALF: Oh, that show! Thanks!

ED: I understand you brought some clips. Would you like to set them up?

There’s no laughter during the exchange. There’s a little bit at the beginning, for reasons I can’t fathom at all, but the bulk of it is literally just these two promoting the very show we’re already watching. It’s really odd. Did this air on a special day and time or something? Why tell the audience that the show is on Mondays at 8 if they already tuned in on Monday at 8 to hear that announcement? And even if it did air on a special day and time, did they have to be so artless about reminding the audience when they could watch? Especially since this episode just began and is nothing like the main show anyway?

I can imagine this kind of thing working well enough as a sort of wink to the audience at home, some gentle fun poked at the idea of self-promotion, but in order for this to be considered meta comedy, or a joke at the expense of shitty talk show interviews, they’d either have to acknowledge it openly, or already have earned a reputation for doing these kinds of jokes.

ALF doesn’t and hasn’t. He literally just sits there letting his guest star tell him how popular his show is. Oh, and then we get to watch some pieces of it. Such as a string of out-of-context bullshit like ALF making dog noises, and performing his classic “filling Willie’s tub with liquidy feces” routine. Classic television all around.

Then he tells Ed to get him some fucking water, giving us all a nice display of what it must have been like to work with Paul Fusco.

Before Ed returns, let me ask this: do you expect ALF to perform Carson’s “Carnac the Magnificent” character?

OF FUCKING COURSE WE ALL DID.

He’s Melmac the Magnificent, which doesn’t even qualify as a pun. That certainly bodes well for this famously pun-heavy routine.

Keeping up with the sharp satire that has defined the episode so far, we get a joke about Gorbachev’s head, and then an observation of that some James Bond movies aren’t very good. Whose toes will he step on next?! There’s also some incomprehensible joke whose punchline is palomino. (“What did Trigger sue Roy Rogers for?”) If anyone can explain that one to me I’ll either be forever grateful or sorry I asked.

My favorite part of this sequence is the fact that ALF has so much trouble opening the envelopes. No, that’s not part of the joke…just a logistical bind Fusco & Co. fenced themselves into by deciding to steal this bit.

See, as Carnac, Carson would hold an envelope up to his head and “divine” its contents. Basically this meant he’d think for a second before saying a word or phrase that was meaningless on its own. Then he’d open the envelope and read what was printed inside…revealing whatever he “divined” a moment ago to be a punchline to that joke.

Because it’s such an immediately recognizable piece of Carson’s late-night persona, and because it consists of just a handful of silly jokes spread out over a long period of time, it makes sense that ALF would want to tap into it.

However ALF is operated by two people, with Paul Fusco controlling the mouth and the left hand, and somebody else controlling the right. That’s nothing too strange; almost any of Jim Henson’s creations with two functioning arms were controlled the same way. It doesn’t require much in the way of coordination between the two puppeteers because only one arm tends to have anything important to do; the other is just given “life” by the secondary puppeteer so that it doesn’t hang dead and ruin the illusion.

Additionally, ALF (like, again, most Muppets) is controlled by people who can’t “see” what ALF sees. This means that complex interaction with objects needs to be limited, because, if it’s not, you can very easily end up with the puppet “looking” in the wrong direction because the object isn’t exactly where it needed to be, or seeming to focus on one thing while his hands do another.

So with all of that being said, you can imagine how complicated it might be for ALF to find an envelope, pick it up, hold it, rip it open, pull out a card, and hold that card up to his face before reading it.

The editing makes this difficulty obvious, as each time ALF reaches into the envelope, we cut to a slightly different angle to hide however much time it took Fusco and his unfortunate assistant to perform this unforgiving task. Sometimes before the cuts, though, we see ALF’s hand gripping helplessly at the card it can’t find. What a tremendously shitty show this is.

There’s also the lovely fact that Ed McMahon can’t muster up even polite laughter at this shitty routine, whereas Carson’s performance of it had him bellowing. That must just be coincidental, though, I’m sure, and can’t be worth reading into…

Then we get another one of those title cards. In this one ALF is climbing a factory that makes novelty heroin needles.

ALF brings out some guests that are probably familiar to the Tonight Show audience, and then shows clips of his own show because fuck you. Each guest leaves early, which is very rude because they didn’t take me with them.

One of them is Dr. Joyce Brothers, very well known for her talk show appearances and one of the first “celebrity psychologists,” if not the first. She paved the way for folks like Dr. Phil, but we can’t really hold that against her. She knew not what she did.

The second guest is Joan Embery from the San Diego Zoo. And man, she’s fucking terrible. I feel bad saying that, but it’s true.

I actually had to look her up to make sure this was actually her and not some shitty actress playing her, because I remember her pretty well from old clips, and she was always a delight.

Embery made a habit of bringing animals onto The Tonight Show, sometimes for novelty purposes (a talking bird, for instance, for Carson so spar with), but usually to just talk about it, introduce it to Carson (and the audience), and to let Johnny humorously engage with it.

She was great.

Really, she was. In looking her up I found myself watching video after video of her appearances. She was an incredibly charming and fun personality.

It’s no wonder that she caught on with The Tonight Show; she was a woman who had a true passion for and deep knowledge of animals, and who also happened to be very well-spoken, very warm, and quite attractive. She was made for exactly this kind of borderline-celebrity status. She was an easy pick for a recurring guest, and indeed some of Carson’s most memorable moments involve animals…thanks to Embery.

Here, though, she’s awful. She’s such a terrible actress in her scene that I honestly thought they paid somebody’s niece to come in rather than hire the woman herself.

But I can’t really blame her. Embery wasn’t an actress…ever. She was herself.

She didn’t play a part for Carson; she was a pleasant human being with knowledge to share and unfamiliar animals to introduce to the crowd. We liked her because she was who she was.

It’s not surprising at all that having her recite stilted dialogue to a puppet while an ordinary housecat sits sedate in her lap would be a disappointment. They bothered to bring Embrey on, but only so she could do the kinds of things she wasn’t comfortable with or good at doing. Great job, ALF.

This is actually the problem that “Tonight, Tonight” and its sister sequence in “We Are Family” inadvertently spotlight; ALF doesn’t improvise.

There’s a reason Johnny Carson is legendary. It’s the same reason Stephen Colbert is now, too. And David Letterman. And Conan O’Brien. As much as all of these men benefited from a stock of great writers, scripted quips can only get you so far. Once you get a guest — or an animal — on stage with you, something unexpected is going to happen. That’s when the talent of the host — specifically, the talent for quick thinking that doesn’t sacrifice wit — is really tested.

Embery doesn’t get to be herself or bring an actual animal because that can’t happen with ALF. As much as Paul Fusco is inviting us to view this proof of concept for Up All Night! With Gordon Shumway, he’s showing us exactly why it won’t, and can’t, be very good.

Because ALF isn’t real, ALF can’t react. Because Fusco doesn’t improvise, ALF has to stick to a script. Because ALF is chained to a desk, nothing can happen that isn’t rigorously planned in advance.

People don’t tune into late night television to watch pre-written banter. They tune into sitcoms for that. When they tuned into Carson, or into Letterman, O’Brien, Feguson, or Snyder, it’s because they were tuning in for the host. Sometimes something magical would happen…other times we just wanted to spend an hour or so with them.

ALF, by virtue of the fact that he’s a puppet being operated by an egomaniac, cannot generate magic. And “Tonight, Tonight” proves that nobody in their right mind would want to spend an hour with him.

ALF then goes out of his way to smash “Johnny’s cup,” and Fred De Cordova (Carson’s real-life producer) comes out to beat ALF to death with a red phone.

Actually, it’s Johnny on the other end of the line. We don’t hear him, but it’s a brief phone call anyway. Which is probably good, since he’s apparently chewing ALF out for his misbehavior during the broadcast, which means Johnny’s making a very expensive call from a parallel universe in which The Tonight Show airs live.

Johnny tells him to fuck fucking up, and there’s a freeze frame of ALF in a panic with a TO BE CONTINUED title.

We’re also treated to some narration in which ALF says to tune in next week to see how he gets out of this jam, presumably for the sake of all the illiterate people who are not doubt watching ALF.

So, hey, for some reason this unedited set of DVDs has “Tonight, Tonight” in its two-part version rather than as it originally aired. I don’t think anything’s missing — correct me if I’m wrong — but it means I get a whole week before I need to watch the rest of this shit, so I’ll take it.

That’s right, motherfuckers. There’s…

But before I leave you…what is a clip show without clips? Clips are grand!

Actually, a clips show without clips is an episode consisting of all new content, which is without exception the superior offering.

BUT ANYWAY HERE ARE SOME CLIPS OF MY FAVORITE EPISODES.

ALF secretly breeds Mexicans in the shed so that they will do his chores for him. (From the episode “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard.”)

Willie slowly dies after tumbling into the radiation pool ALF has installed in the back yard. (From the episode “Let’s Make the Water Turn Black.”)

It’s a harrowing half hour when a black man is accidentally admitted to the Tanner house. (From the episode “Mississippi Goddam.”)

ALF drugs Kate in the hopes that he can trick her into sucking him off. (From the episode “I Put a Spell On You.”)

ALF systematically stalks and murders beloved TV icons, and won’t stop until Paul Fusco is given a talk show. (From the episode “Star Star.”)

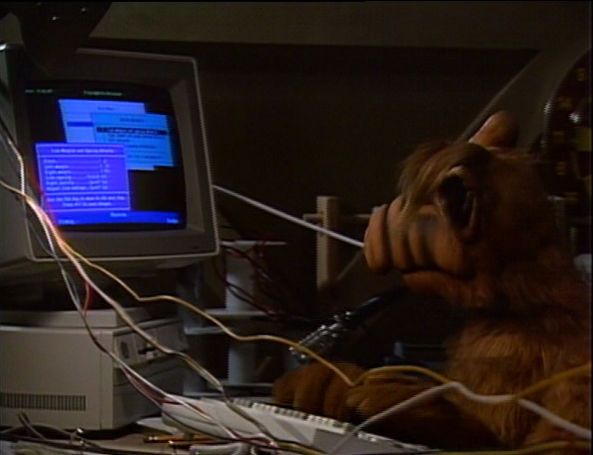

After stumbling upon Willie masturbating in the shed to a copy of Leisure Suit Larry, ALF becomes addicted to computer pornography. (From the episode “Thank the Lord for the Night Time.”)

ALF escapes his court-mandated castration. (From the episode “Fix You.”)

ALF has a long and meaningless conversation with a character we will never see again while the production crew chokes painfully and coughs up blood in this sealed room full of dry ice. (From the episode “Try Not to Breathe.”)

Having been rendered redundant by Jake’s arrival, Brian is wrapped in a pool tarp and buried in Mr. Ochmonek’s yard, never to be referred to again. (From the episode “Bye, Bye, Baby.”)

Uncle Albert accidentally finds Willie and ALF engaged in a game of Mr. Meatloaf. (From the episode “I’d Do Anything for Love (But I Won’t Do That).”)

That’s all for now! See you after the break!