Like its predecessor Shaun of the Dead, Hot Fuzz is a buddy comedy masquerading as a genre pastiche. But unlike Shaun of the Dead, it’s at times difficult to distinguish from the films that inspired it.

Whereas that earlier film built an entirely independent narrative about its characters that just happened to unfold alongside a zombie apocalypse — and whereas The World’s End built an entirely independent narrative about its characters that just happened to unfold alongside a body-snatcher invasion — Hot Fuzz is actually what it seems to be. Overall, it’s not a pastiche; it’s a film that has jokes in it, but otherwise fits snugly into one well-defined genre.

Which makes it feel like an outlier in the Blood and Ice Cream Trilogy. It’s not a cop film that keeps encroaching on a smaller, more personal film; it’s a cop film. In fact, it’s a cop film that keeps getting encroached upon by a slasher film, a whodunit, and a film about a murderous cult.

Shaun of the Dead and The World’s End are both small, quiet films about characters coming to painful terms with who they are, told through the lenses of bombastic, apocalyptic tales that import familiar tropes and set pieces for our characters to trip over and butt up against.

But Hot Fuzz is a cop movie, through and through, and our characters don’t so much trip over and butt up against imported tropes so much as they incorporate them into their understanding of what’s going on. (They’re cops, after all. It’s what they do.)

All of which probably sounds like I’m coming down hard on Hot Fuzz, but I’m not. I’m a big fan of the trilogy, and, for my money, Hot Fuzz is the best of the batch.

Not my favorite, mind you. I won’t beat around the bush; that honor belongs to Shaun of the Dead, which I just find to be funnier and more charming overall. Hot Fuzz is the more accomplished work, and it hangs together more naturally than Shaun did, but I think those things come at the (relative) expense of the things I enjoyed most about Shaun.

With Hot Fuzz, Edgar Wright made a great cop film. That’s an accomplishment, but with Shaun of the Dead he made a great film called Shaun of the Dead.

In that case, it was a movie in a league of its own, standing as a monument to its own accomplishments. In this case, Wright proved he could do what others have already done, and do it just as well.

Impressive, but that holds the film back from hitting the way that Shaun did. Its sights are set necessarily lower.

The World’s End, as long as we’re ranking, is easily my least favorite, so tune in for what’s sure to be a fair and balanced review next week.

So, there, we’ve definitively and without room for argument ranked the films. Now we can actually start talking about this one.

Hot Fuzz again sees Simon Pegg and Nick Frost in the lead roles, and — wisely — they both play very different kinds of characters than they played in Shaun of the Dead. This allows the film to feel less like a follow-up and more like something that should be judged on its own merits (for better or for worse). That’s as it should be, because wherever you’d personally rank it in the trilogy, it’s an exceptional and rewarding film in itself.

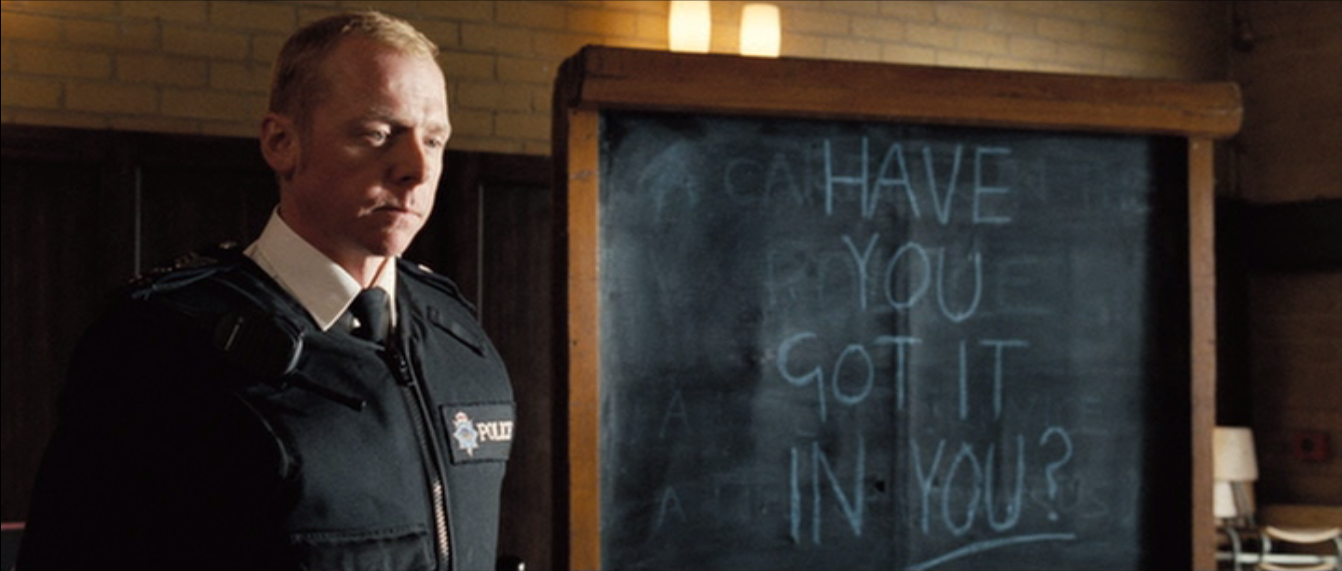

Pegg is again our protagonist. Here he plays Nicholas Angel, a restlessly devoted police officer whose adherence to the letter of the law costs him his relationships, his friendships, and — as the film begins — his job in London.

The London scenes are the most outright parodic, which definitely gets the audience laughing and receptive, but there’s still some nice world building that occurs here, particularly as Angel’s superiors (played in succession by Martin Freeman, Steve Coogan, and Bill Nighy) are called in and dance around the issue a little less each time, resulting in Nighy coming right out and saying that Angel’s being transferred because he makes the rest of them look bad.

His new post is Sandford, Gloucestershire, a small village whose humble police force — to put it politely — Angel makes look even worse. Here he’s partnered with Danny Butterman (Nick Frost), a simple oaf who takes a fast shine to Angel’s professionalism and experience, and who becomes very quickly the only one Angel can rely on.

It’s a great setup, and Pegg and Frost inhabit their characters thoroughly. In spite of our memories of shlubby old Shaun, who needs the literal collapse of society to shock him out of his malaise, Pegg is completely believable as supercop Angel.

His youthful appearance might seem a bit out of place on box art and in stills, but in the film it serves only to heighten his talent and devotion to the job. He’s not a man who’s spent a full career becoming a great police officer; he was a born police officer, as we learn when he tells Danny about his police pedal car. This is his calling.

Which is also Angel’s problem.

In addition to the interference it causes with his personal life, Angel isn’t happy. He knows nothing of the world outside of policework, and can’t even say goodbye to his ex-girlfriend without slipping into investigation mode. (To be fair, they were at a crime scene at the time.) His life becomes painfully lonesome and empty the moment his shift ends, and when he’s on duty his talents go unappreciated, resulting in London shipping him off and Sandford tormenting and bullying him.

There’s only one thing he’s good at, and it’s something everybody resents him for.

Well, everybody apart from Danny, whose relationship with Angel isn’t just the centerpiece of the film, but its sincere, impressive emotional core. As great as Pegg is — and he is great — in this movie, it’s Frost’s Danny Butterman that stands out as the most impressive creation.

Shaun had more than a passing similarity with Pegg’s role in Spaced. They were both aimless slackers who had more ambition than they had motivation, and they were content, ultimately, to get older without necessarily growing up. Angel, obviously, is the exact opposite; he was born a grizzled professional, and couldn’t begin to imagine idle time. (Prior to meeting Danny, he ain’t even seen Bad Boys II!)

Frost’s character here, however, hearkens back to his character in Spaced: Mike Watt.

Both Mike and Danny are in some “lower” branch of service to their country (Mike in the Territorial Army, and Danny in a rural police district), but long to join the ranks of the big leagues (the real Army for Mike — who can’t enlist due to an injury — and the “proper action and shit” of big city police work for Danny).

And in each case, they’re disarmingly fragile, desperate for acceptance and respect.

Danny is far more than a re-painted Mike Watt, though, especially since Mike had friends. He’d still fall apart, but he had a group that needed him. He had a place. Danny does not. At least, not at first. And his growth over the course of the film — from ambling boob to hero who is willing to sacrifice himself — is easily the most significant growth experienced by any character in the trilogy. Danny’s arc is human, painful, hilarious, and adorable.

Danny growing from comic-relief-fat-guy to effective law officer would be enough, but what really gives it heft is the fact that it also tests his loyalty. He is, after all, the son of department head Frank Butterman…who clashes politely with Angel over his interpretation of a recent spate of deaths.

Angel feels they’re related homicides, but Frank reminds him that Sandford is a quiet town. Accidents happen. There’s no reason to jump to conclusions.

The rest of Sandford’s finest agree with Frank; they’ve worked here far longer than Angel, and haven’t seen any evidence that this is something to get worked up over.

Danny, however, listens to Angel. He helps him identify collections. He even spends his birthday combing through evidence with him (a more significant suggestion of Danny’s growth than it probably seems). And, ultimately, he sides with Angel over his father, culminating in what’s sure to be the most affecting homage to Point Break in film history.

Frank, it turns out, is the murderer. Kind of.

The film takes its time getting around to the deaths, which works to its great favor. The overt parody of the early scenes give way to a fish-out-of-water (or big-cop-in-a-small-town) film in which Nicholas Angel must re-learn his role as a police officer in a context that doesn’t need — and is not receptive to — his heavy hand.

It leads to some great comedy, as you might imagine. His first night in Sandford sees him clearing a local pub of its underage patrons, leaving the owners to seethe at him while he enjoys a cranberry juice in their now empty establishment. It’s both funny and important to the way the plot develops.

While Angel adheres to the letter of the law, the pub owners appeal to the spirit. They argue that it’s better to have the kids in there, where they can be supervised, than out drinking on their own somewhere, causing trouble or getting hurt. In other words, they’re breaking the law, yes, but they’re doing it for the greater good. (The Greater Good.)

This is the conflict the film sets up; Angel’s unwavering respect for the law as written, and Sandford’s understanding of the law as a roadmap to a more pleasant society. Structurally speaking, Angel should end the film by learning to loosen up, and respecting the human element above legal mandates.

Instead, we learn that it’s not Angel who needs to loosen up at all; it’s the villagers, who dispose of or murder unsavory characters in order to preserve the respectable image of Sandford. The letter of the law is set up, initially, as the too-harsh avenue of interpretation, but the film shows us that it’s actually the other way around; respecting only the spirit of the law is what leads to atrocity.

It’s an exaggerated outcome, to be sure, but the fact that Hot Fuzz is a comedy means there’s no need to dismiss it as slippery-slope panicky nonsense, even if it does feature a bloodthirsty cadre that kills people for having annoying laughs or for thinking about moving away. Whatever larger points it’s making about the letter/spirit debate apply only to its own universe.

The killers in question are the Neighborhood Watch Alliance, operating under Frank Butterman. That’s the kind of reveal that requires a lot of misdirection, which Hot Fuzz manages to be both really good at, and frustratingly sloppy about.

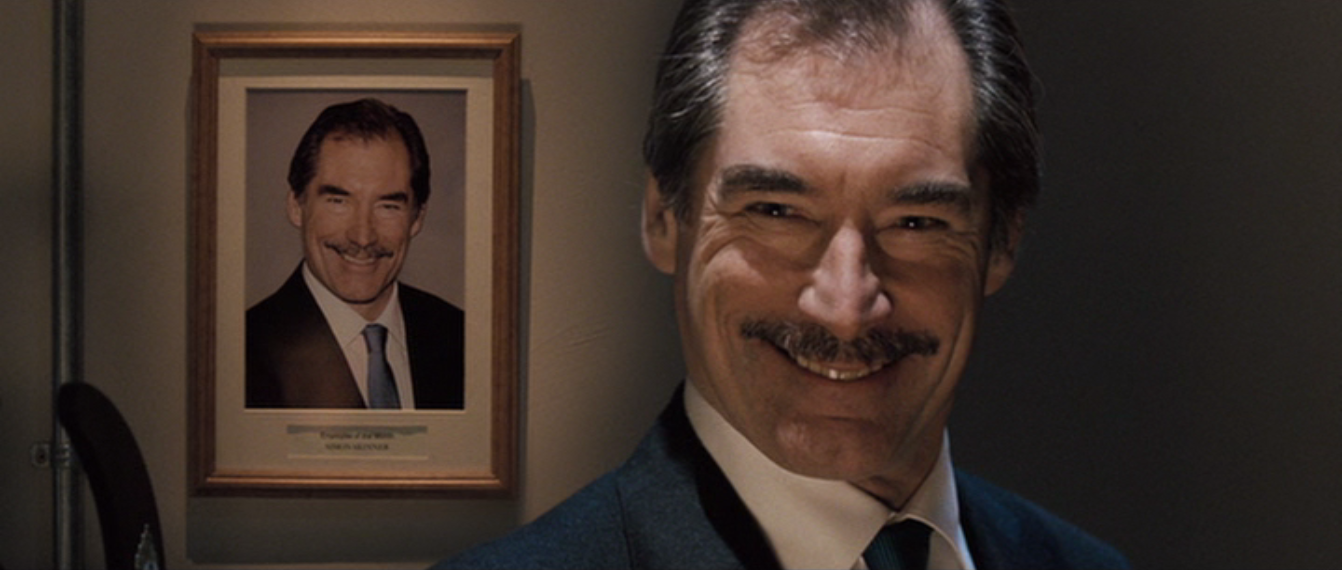

I can sum up where it works in two words: Timothy Dalton. Admittedly there’s a lot of misdirection that the film handles well, but Dalton’s character is misdirection on legs, and he’s absolutely perfect at it.

He plays Simon Skinner, the owner of the local supermarket, and he introduces himself to Angel by saying he’s a slasher…of prices! From Angel’s very first day on duty, Skinner knowingly toys with him. He delights in it. He knows full well the oily, sneaky bastard that he is, and it’s an awareness that fills him with pride.

He loves being a shit.

At first he’s likely just attempting to assert himself. He’s an important figure in the town, and he wants people to be so strongly aware of that that they cower from him.

In fact, we see that he has this exact effect on other characters in the film, in particular George Merchant and Tim Messenger, two of the NWA’s later victims. (The latter immediately deflates when Skinner enters the scene, and it’s such a perfect moment of acting for Adam Buxton, shifting from mindless, sunny reporter to beaten little brother in the blink of an eye.)

Skinner drives smugly by crime scenes, making sure Angel hears that he’s listening to music related to the crime. He drops knowledge he shouldn’t have. He winks and leaves Angel behind, knowing that he’s both piqued the young cop’s suspicions and also left him nothing to work with.

He plays a game during this section of the film — which drifts smoothly into legitimate slasher territory — and it’s a game he relishes.

Why? Because he knows he can’t lose.

Skinner sets himself up as the prime suspect, establishing himself in that role well before there’s even a death to investigate. And he does this for the purposes of misdirection. As long as Angel suspects him — and Skinner ensures that he does — the rest of the NWA is safe to carry out their business. And should Angel ever feel that he’s pulled enough evidence together to take Skinner in, as he does at one brilliantly handled point in the film, Skinner has his supermarket surveillance tapes to clear him of any wrongdoing.

He’s a decoy, and an incredible one. He’s involved with the killings, and indeed sets himself up to seem like the killer himself, which is ultimately what keeps him and the rest of the cult safe. The more he frustrates Angel, the less Angel has an idea of what’s really happening.

This misdirection comes to a head in the aforementioned arrest scene, which sees Angel laying out all of the evidence and connections he’s found, working carefully and deliberately through a complicated theory that positions Skinner as the one link between all of the victims, the single person who would benefit from their deaths, the only one in the entire village with the means, the motive, and the madness to pull it off.

…only he didn’t do it.

Angel’s defeat is one felt by the audience, which makes it easy to miss the fact that Wright (and co-writer Pegg) spun not one but two satisfying mysteries out of the same set of clues and plot points.

The first is the false one that Angel outlines here. Every detail fits, and a shorter film could have ended with Skinner’s arrest without it seeming cheap. (That movie probably wouldn’t be as funny, though.) The only reason it doesn’t work is that the filmmakers say it doesn’t; information that is yet to be revealed will throw light from another angle over what we already know, and cause it to cast a very different shadow: Frank Butterman and the NWA are working together as a murderous team.

That’s impressive writing. Even the best mystery writers have difficulty making their own pieces fit together. Raymond Chandler was famously asked by the filmmakers adapting The Big Sleep who killed one of the novel’s characters. Chandler replied that he didn’t know.

So for Wright and Pegg to spin a mystery that doesn’t just add up but that adds up in two different ways…that’s a hell of an achievement.

But that’s also why Hot Fuzz is maddening. Two solutions requires two climaxes. Hot Fuzz has what feels like around 30.

It’s the kind of movie that ends again and again, but then keeps going. And while the first 2/3 of so of the film is tightly and intricately constructed, the final stretch feels loose and in need of editing.

It feels like Wright and Pegg wanted many things to happen in Hot Fuzz, and so spend their time building toward those things. That’s not a problem; in fact it’s impressive that — if this is true — the buildup was so masterful, and all the time spent sewing seeds was actually riveting and fun. But it does mean that their big set pieces toward the end don’t seem to have had as much thought put into them. Wright and Pegg worked hard to get us where we needed to go, but once we get there, there’s not much to see.

Of course, that’s an odd thing to say about a climactic shootout that spans the entire village and ends with Timothy Dalton piercing his jaw on a spike, but the problem is that there’s little else at play. It’s a shootout…and that’s almost all it is.

There are small touches (the villagers standing where Angel met them on his first morning; the fact that Angel uses creative non-lethal takedowns in every case), but we’re still just watching a shootout.

In Shaun of the Dead, we were never just watching a zombie movie, but Hot Fuzz definitely becomes an action film for a too-long stretch. And that’s disappointing, because this is a creative team that is fully capable of working on several levels at once. The slasher movie also being a cop movie is an example of how well they can handle tonal discrepancy, but here we slide right into action gear and…just kind of stay there.

It also doesn’t help that the film comes to a dead stop multiple times, with one character or another insisting that the action halt so they can deliver some kind of speech…only for the action to swell up again. In fact, three times Frank is the character who does this.

Hot Fuzz should be savvy enough to realize that this either needs to be undercut in some way, or rewritten entirely. Instead, it just lets it happen. Over, and over, and over again. An inventively shot and written film by an incredible team of talent suddenly, and disappointingly, decides that good enough is good enough.

As a result, Hot Fuzz feels overlong, and it makes me pick at things I wouldn’t otherwise be very concerned with (such as the strangeness of the sea mine blowing up the entire precinct without hurting anyone inside). It also makes Danny’s sacrifice — taking a literal bullet for Angel — feel less potent than it should. As a mark of his growth, it’s great. As a potential tragic end to the film it’s quite moving. But as it stands it’s several endings too late and the audience is already restless. It still works, but it loses a good deal of its power.

Needless to say, Hot Fuzz isn’t much poorer for dragging its feet toward the end, and I admit that a sloppy landing does nothing to work against the mastery demonstrated by the rest of the film. It’s a great watch with a stellar soundtrack and an incredible cast, and, like Shaun of the Dead, it’s full of internal echo that you may not notice without multiple viewings.

It’s also got the strongest central relationship in the trilogy: that between Angel and Danny.

Evidently an earlier draft of the script had Angel falling in love with a woman in Sandford; when she was written out, many of her lines were given — unchanged — to Danny. This is likely why the scene of the two of them in Danny’s house seems to be building toward a kiss, but it’s also what gives their interactions such affecting power.

Had Angel been saying these things and opening up this way to a woman, it would have been just another movie relationship. But as it’s Danny, the only human being who treats Angel like a friend, it’s sad, and pretty touching.

These are two people who have each built lives for themselves, but who desperately want to connect. And when they do, it’s something a lot like love.

You know what? To hell with that. It is love. Not sexual or romantic love, but it’s love all the same.

Hot Fuzz is a love story about two men who each find what they’re looking for in each other. The fact that the film at no point plays this for overt laughs is an achievement of restraint, and one I think we could all learn from.

It’s a joyfully gory mystery wrapped in a buddy cop film, with funny things to say about the genre’s conventions and impressive insight into how even a lifelong putz like Danny Butterman can find a place for himself in the world.

It’s not as tightly constructed or surprising as Shaun of the Dead, but it’s impossible to overlook the many, many things that it does exactly right.

I can’t imagine many Shaun fans were disappointed by this one. If they were, I wonder what it was that they saw in Shaun.

It would be a long six years before we got our conclusion to the trilogy with The World’s End…an understandably divisive film that I look forward to discussing next week.

Well, I say I look forward to it. Let’s see how I actually feel when I write the damned thing.