Fiction into Film is a series devoted to page-to-screen adaptations. The process of translating prose to the visual medium is a tricky and only intermittently successful one, but even the fumbles provide a great platform for understanding stories, and why they affect us the way they do. This month’s piece was graciously provided by reader Viktor Tsankov.

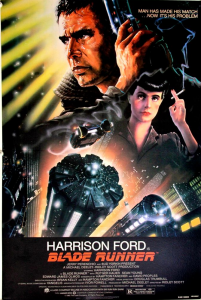

It is difficult to deny Blade Runner. A cult classic from the director of Alien that stars Han Solo/Indiana Jones in his prime, selected for preservation by the Library of Congress, one of the first cyberpunk works that arguably defined the aesthetic of the genre, consistently voted one of the best sci-fi films by critics and sci-fi fans alike, and influencer of works from the Battlestar Galactica re-imagining to the Ghost in the Shell films, Blade Runner is an aesthetic cultural touchstone that pales in comparison to the work it is based on and the works that came after it.

It is difficult to deny Blade Runner. A cult classic from the director of Alien that stars Han Solo/Indiana Jones in his prime, selected for preservation by the Library of Congress, one of the first cyberpunk works that arguably defined the aesthetic of the genre, consistently voted one of the best sci-fi films by critics and sci-fi fans alike, and influencer of works from the Battlestar Galactica re-imagining to the Ghost in the Shell films, Blade Runner is an aesthetic cultural touchstone that pales in comparison to the work it is based on and the works that came after it.

Before going any further, I don’t want to give the impression I think it is a bad film. On the contrary, Blade Runner is a beautiful, empty mess. A more faithful adaptation of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? might have had a difficult time inspiring the way Blade Runner has. What the film did is create a stylistic foundation, it teased a larger, more intricate, world that it never capitalized on, and it let its fans’ imaginations run wild.

Its narrative emptiness, its multiple versions, and its messy architecture all came together to create a uniquely subjective experience of a narrative. A viewer is largely free to choose the truth of the film in ways that would not be possible with other films, and that would be even more difficult with the singular novel.

For this piece I have watched five versions of Blade Runner: 1) the original US Theatrical Cut (1982), 2) the prototype Workprint (1982), 3) the International Theatrical Cut (1982), 4) the Director’s Cut (1992), and 5) the Final Cut (2007). The differences between these versions are smaller than one might expect considering how many releases there were, but when there are significant differences I will point them out.

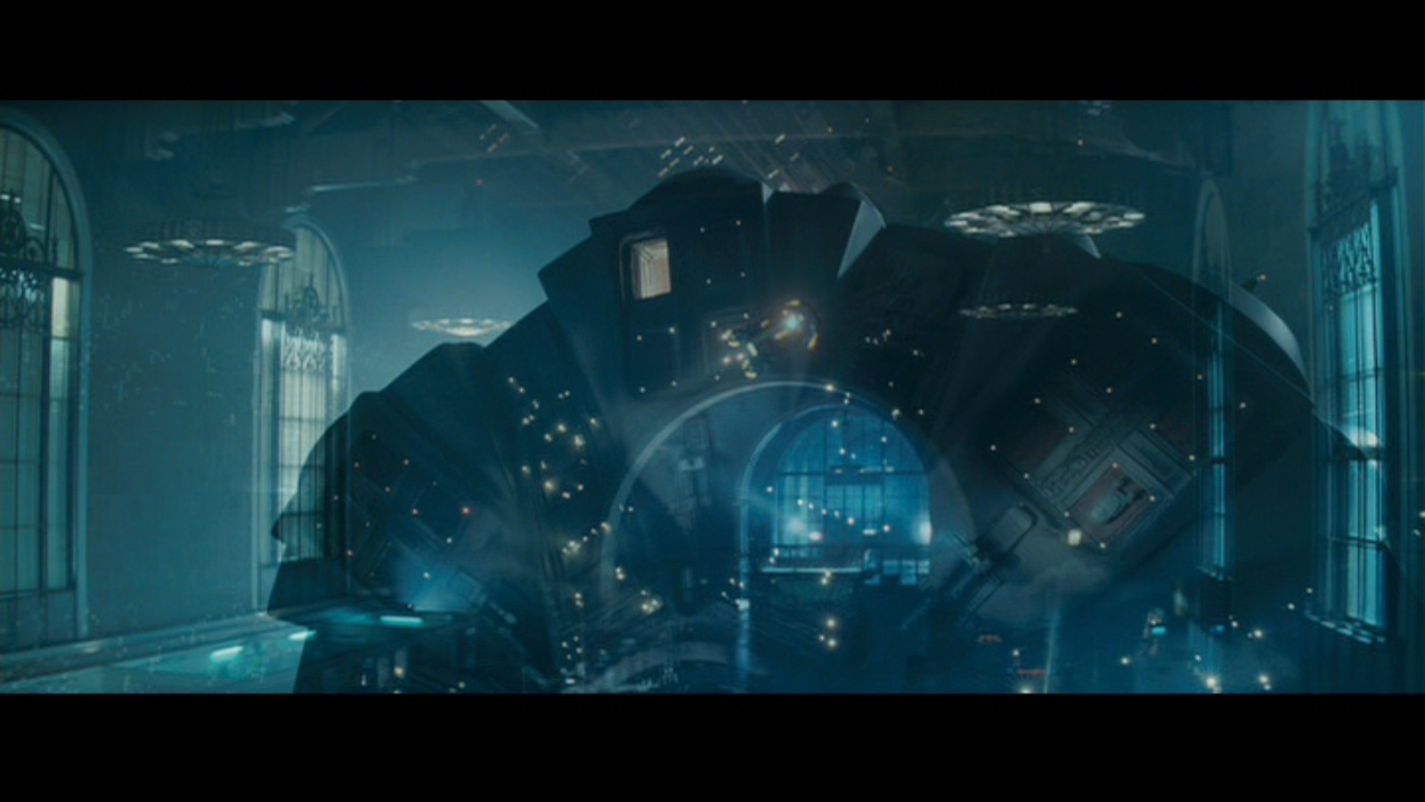

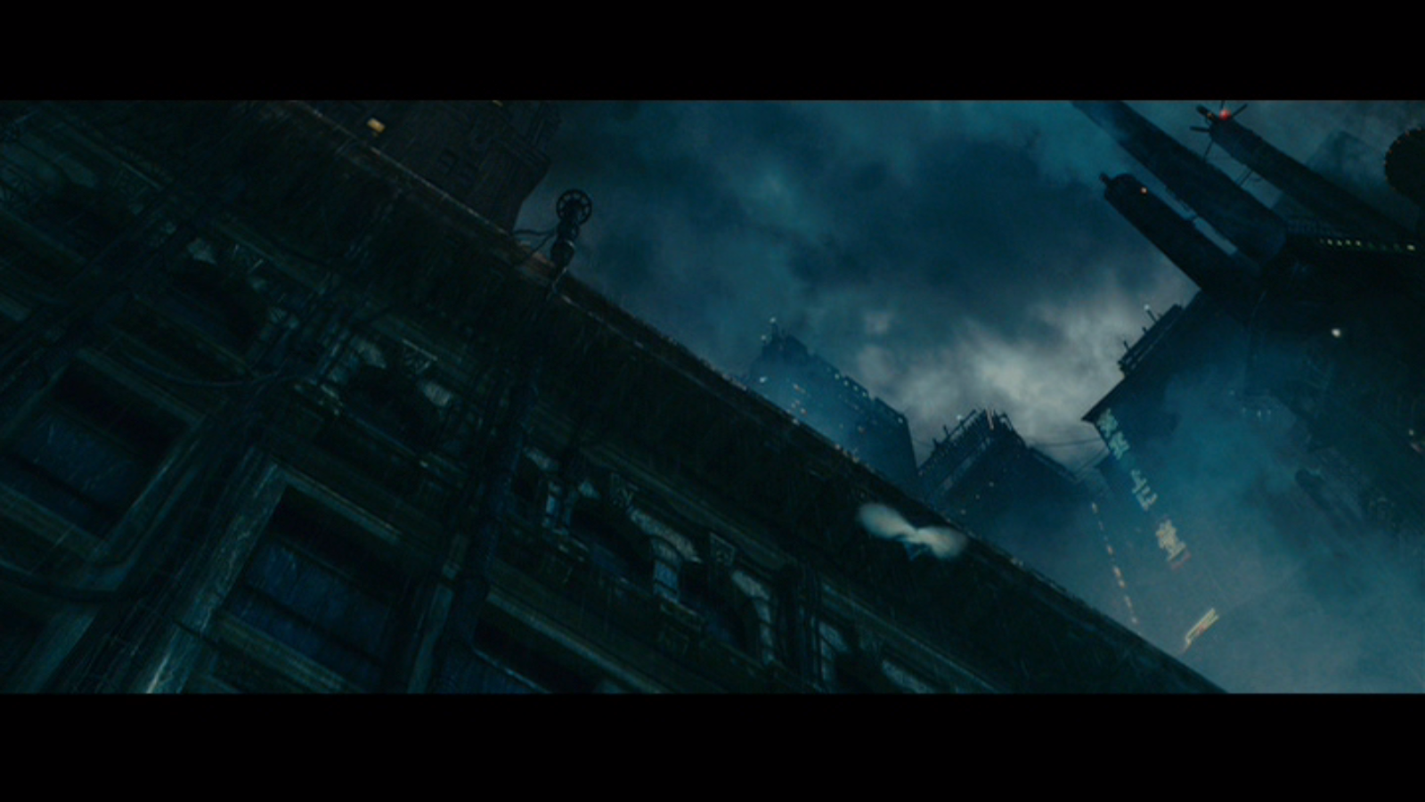

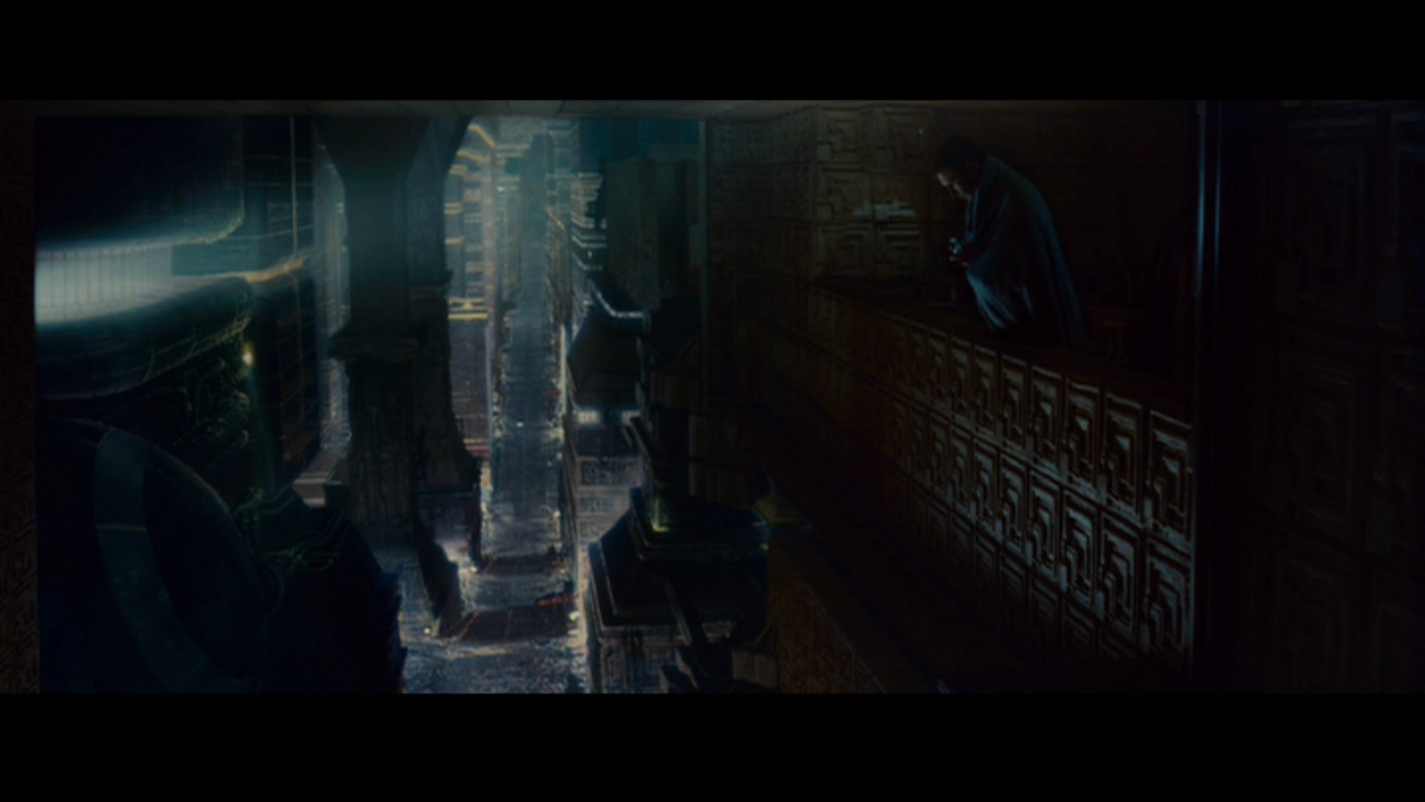

One of the first ways in which there is an important difference is the messy architecture that I referred to earlier. Blade Runner seems to be purposefully made to mess with an audience’s sense of place. The story is told over at least three nights and three days, although time is really indeterminate. It rains every night except for the first night and is sunny every day. The first image we are greeted with is fire shooting up from skyscrapers into the night sky. There is fire in front of Taffey’s place as Deckard runs out to chase Zhora.

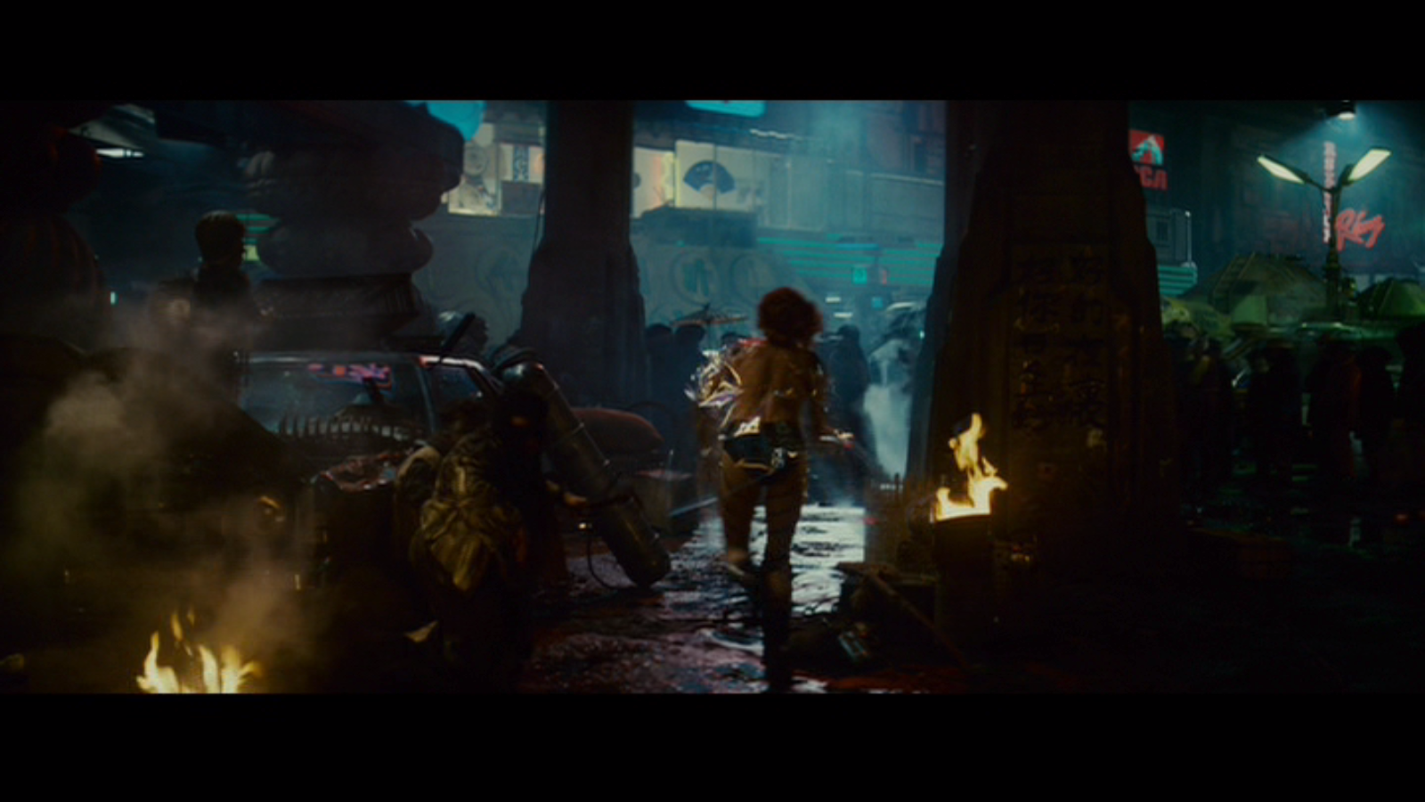

And there is fire outside of Sebastian’s place as Pris is walking there.

When Pris walks to Sebastian’s, we see her pass by a fire truck and a police vehicle, and yet they do not see, or do not care about, the fire in the street.

In general, people seem to care very little about what is going on around them. Deckard chases after Zhora brandishing a gun in his hand, and people hardly notice. No one screams, no one gets down, people just seem annoyed that he is pushing them out of his way. At a later point in the film when Deckard has parked on the street, a group of people climb onto his car while he is still in it and start trying to take it apart. The people are as blasé as about life as they are about death.

Some of the more interesting elements seem to be due to error. The scene that introduces Roy Batty has a stray finger on his coat that belongs to no one.

This finger exists in every version but the Final Cut.

Not only that, but it is mirrored in the scene where Roy is talking to Tyrell, only this time the finger actually belongs to someone.

Similarly, at Roy’s death in the rain at the end of the film, he lets go of a dove that then flies into a clear, blue sky.

This is then corrected in the Final Cut to show the rain that should have been there.

Although these two scenes were corrected in the Final Cut to remove the stray finger and to add in the rainy sky, it should be noted that the Final Cut wasn’t released until 25 years after the original. For 25 years, no matter which version of Blade Runner one saw, they would have experienced these weird moments of things not lining up.

And those are just the obvious visual inconsistencies. Blade Runner is also chock full of film techniques meant to give the feeling of otherness.

The film begins with flashes to a mysterious man with his back turned, who we later learn is Dave Holden, the other Blade Runner. In his interview with Leon, the replicant, we get a brief moment of audio echo or overlap. When Deckard does his interview with Rachael, we get two quick dissolves and more audio overlap.

Roy gets a dissolve after he has killed Tyrell and Sebastian as a transition to Deckard.

When Roy dies he gets a final dissolve with Deckard so that both are in the same shot.

Rachael is completely washed away by light when she is at Deckard’s place after killing Leon.

You can barely see the outline of her face when comparing the two, but it happens a couple of times in the scene. Light from outside flashes towards her and washes out Rachael and the background. When Deckard plays the piano in every version but the Workprint, it starts out seeming like non-diegetic music until we see him pressing the keys and we get diegetic and non-diegetic music in the same scene.

These techniques create a sense of distance. Some of them have a simple purpose, like the dissolves in the Rachael interview being a shorthand for time passing. But most of them are there just to keep the audience active. There is a lot of information being given and a viewer has to pay attention to be able to take it in. Put another way, it makes the setting not only seem alien, but untrustworthy. The camera lets us see the seams of the world. This has the benefit of making everything seem all the more fantastical, but the drawback of putting off people who need a more concrete setting to suspend their disbelief.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? has a less fantastic setting. The world of Androids is mostly colorless and nondescript. The radioactive dust in the air is causing the world to crumble, and most of humanity has either died out or left the planet for the colonies. Where Blade Runner had busy streets filled with people who didn’t care about the fantastical things happening around them, Androids has a few people living desolate existences trying desperately to connect and feel something.

The crushing loneliness that Deckard and other characters feel is reflected in the decaying world, the empty silences. Silence “flashed from the woodwork and the walls; it smote [Isidore] with an awful, total power…it oozed out, meshing with the empty and wordless descent of itself from the fly-specked ceiling.” Isidore “experienced the silence as visible and, in its own way, alive.”

People feel the death of their infrastructure and the world so acutely, that they try to live as close to other people as possible. The very notion of emptiness and silence is utterly terrifying to them and messes with their minds. The world of Androids is abstract, psychological, and terrifying.

This is where the religion of Mercerism becomes important. Using an empathy box a person is able to become one with Mercer and connect to every other person using the emapthy box. The name half-explains itself; it engenders empathy for other people by having everyone that connects to it feel the feelings of every other person connected.

When someone is happy or sad, they share that feeling with the rest of the empathy box users. This feeling, when all physical evidence is to the contrary, is what keeps people connected, what keeps people wanting to stay alive despite their depressing surroundings. And it manifests itself in other ways.

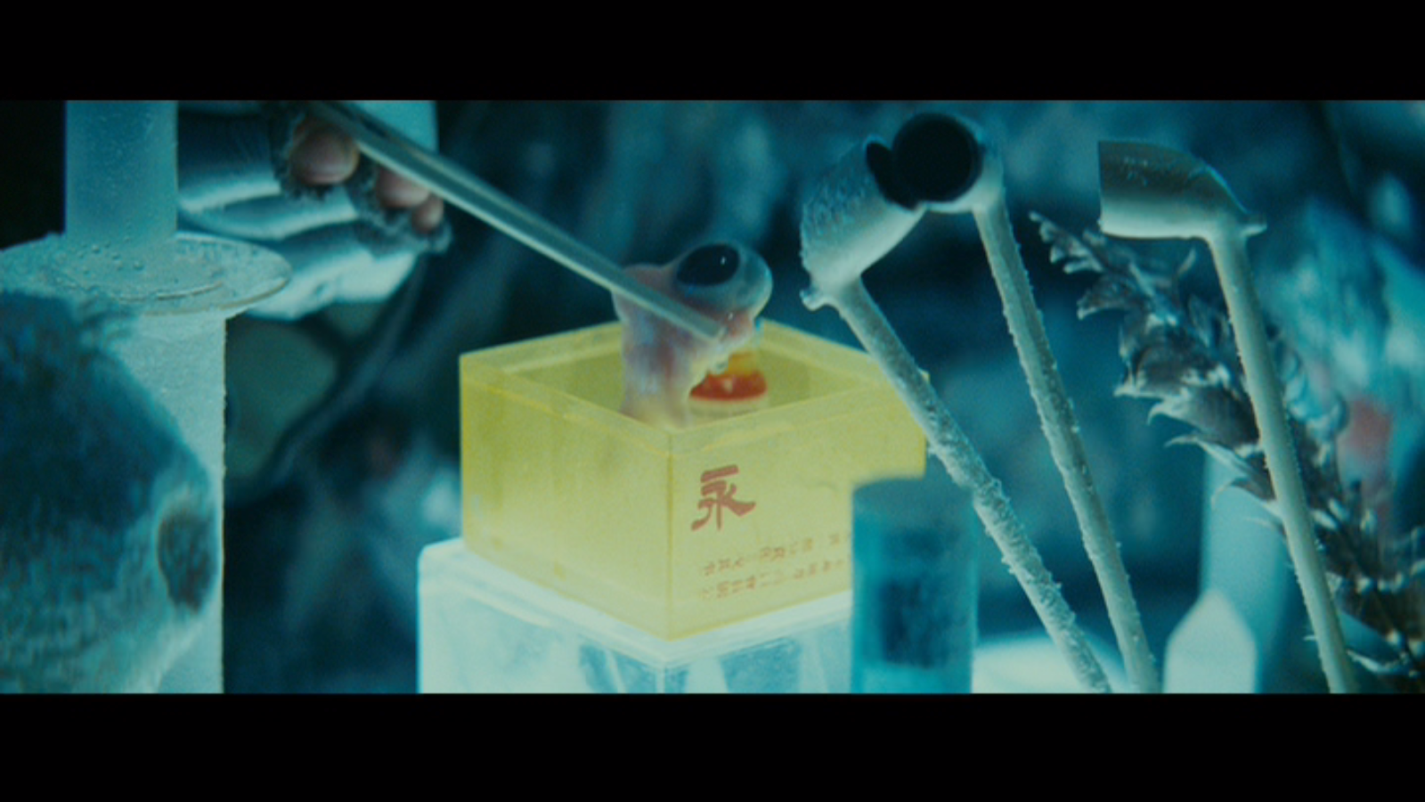

This is where the emphasis on animals comes from as well. Blade Runner has a few allusions to this, as with the artificial owl at the Rosen Association and the artificial snake that Zhora says is much cheaper than a real snake. There are ostriches and ponies and birds on the street that people walk around, but it has no particular meaning to Deckard or anyone else. It is just another part of the fantastical, futuristic setting. In Blade Runner‘s future artificial animals are as or more common than real ones.

In Androids, one has to have an animal, not just from an empathic standpoint of having living things around you, but from a social standpoint, too. And since animals are rare and expensive, it is often the case that people have electric animals. But owning an electric animal, like Deckard’s sheep, is demoralizing. His neighbor feels sorry for him and everyone assumes that others will look down on him. It’s difficult for owners to even pretend it’s alive.

It doesn’t matter how good the animal looks or if it acts exactly like a real one; the knowledge that it is fake taints the affection they might have for it. After Deckard has produced three of the six android corpses he has enough money to put a down payment on a real goat, and Rachael says outright that he loves the goat more than he loves her or his wife. The one thing keeping him going through the ordeal of hunting the androids is the thought that he will get to be with his goat later. For Mercer all life is sacred and he loves all animals, and this translates down to all of the people connecting with him through the empathy boxes.

This is also a defining difference between humans and androids for the novel. Androids in both the novel and film have killed people before they come down to Earth. In the film this is suggested of the six particular replicants that Deckard is chasing, and the rest are ambiguous. In the novel, this is explicitly stated to be the case for any android found on Earth. Androids are given as servants to humans going off to the colonies as an incentive for them to leave the planet, and so any android found on Earth could only have gotten there by killing their human master. Murder committed by androids is similar to murder committed by actual people, but a defining difference is that the androids in the novel are solitary. They care about themselves individually. They do not care about animals or humans or other androids. Humans, on the other hand, have empathy for other creatures, emphasized by Deckard as a group animal trait.

Humans in the novel are closely associated with animals and they empathize with them to a high degree. Pris’ snipping of a spider’s legs upsets Isidore so much that he abandons the androids even after he had decided to protect them. Androids cannot take care of animals. Even if they wanted to, which they do not, they lack the warmth and empathy necessary to keep animals alive, which humans have instinctively. It’s what suggests the humor in the title. The answer to “Do androids dream of electric sheep?” is an obvious no. It seems like a deep question before you’ve read the novel, but since androids care only about themselves, and no further than an individual level, they couldn’t possibly care about artificial animals of a lower intelligence the way humans do.

The title is a joke on human empathy towards anything and everything, including those for whom it would be impossible to reciprocate that empathy.

The replicants in Blade Runner are indistinguishable from humans. Bryant tells Deckard that though they do not begin with emotions, over time they can develop them fully the way a person could, and Eldon Tyrell tells the bounty hunter that they also implant false memories into some replicants so that they more fully believe that they are human. And this is borne out in the film. Roy and Pris kiss.

Leon seems devastated watching Zhora die.

Roy in general goes through all manner of different emotions like anger, contempt, joy, etc.

The opening crawl of the film suggests what a person is meant to feel about androids. They are used for slave labor, they are virtually identical to humans, and killing them is not referred to as execution but retirement.

The words are meant to engender the audience’s sympathy to their plight. Although they have killed 23 people to get to Earth and a bunch more throughout the film, their main goal is to live longer. They have been artificially given four years to live, and they are dying. In his death scene Roy suggests that he has witnessed beautiful and wondrous things that no human will ever witness, and that this has some value. There is poetry in his words and thoughts that can’t be denied.

Even if you consider them ruthless killers, the film also gives you Rachael. Rachael is an innocent. She kills Leon to save Deckard, and is mortified by her actions. She cries when Deckard confirms she is a replicant.

As if our sympathies weren’t with her enough when she finds out her whole life has been a sham, she is also completely alone.

Being a replicant and running away from the Tyrell Corporation means that she is now wanted by bounty hunters; this makes Deckard an enemy, and yet she saves him. It isn’t until after she kills Leon that Deckard says he wouldn’t hunt her; she had no guarantees going into it.

Although it gives mixed messages about the other replicants, Blade Runner wants you to care about Rachael at least. Instead of having her seduce Deckard the way a femme fatale might in any other noir, he forces himself on her. Rachael remains an innocent in the relationship that springs up between them too.

Our feelings on Rachael, at least, are clear. Similarly, Sebastian is an innocent human in the film. He does not kill anyone, and in fact helps the replicants. He takes Roy to meet his maker, and is then mortified when Roy kills Tyrell. Sebastian also has no problems empathizing with the replicants, because he creates his own friends that are not human.

It’s difficult to know what to think about the rest of the replicants. Zhora isn’t in the film long enough to have a defined personality, Leon is violent and cruel, Pris seems to take some joy in making Sebastian feel uncomfortable, and Roy kills Sebastian, our innocent human.

The other humans don’t come off any better either since Bryant doesn’t care about Rachael and bullies Deckard into working for him, Tyrell treats all of his replicants like fun experiments, and Holden in his interview had a mocking, sneering attitude toward Leon. Gaff is a bit more ambiguous since he lets Rachael live with the knowledge that she has only a four-year lifespan, but is otherwise not much of a presence. He speaks only one understandable thing and is otherwise absent for most of the film.

Deckard is the real mystery, and your conception of him changes depending on which version you see.

In all versions he kills the androids, forces himself on Rachael, and vows to protect her later. The two theatrical versions have some short narration. There, Deckard looks down on Gaff and thinks Bryant is a racist. He is surprised at his own feelings since Blade Runners are not supposed to have feelings, similar to how replicants are not supposed to have them. He more and more feels like a killer, and even feels bad for shooting a woman, Zhora, in the back, but these internal moments don’t stop him from killing the replicants. In the versions without narration, it doesn’t even seem like he minds killing them.

In general, the Deckard in the film doesn’t make sense.

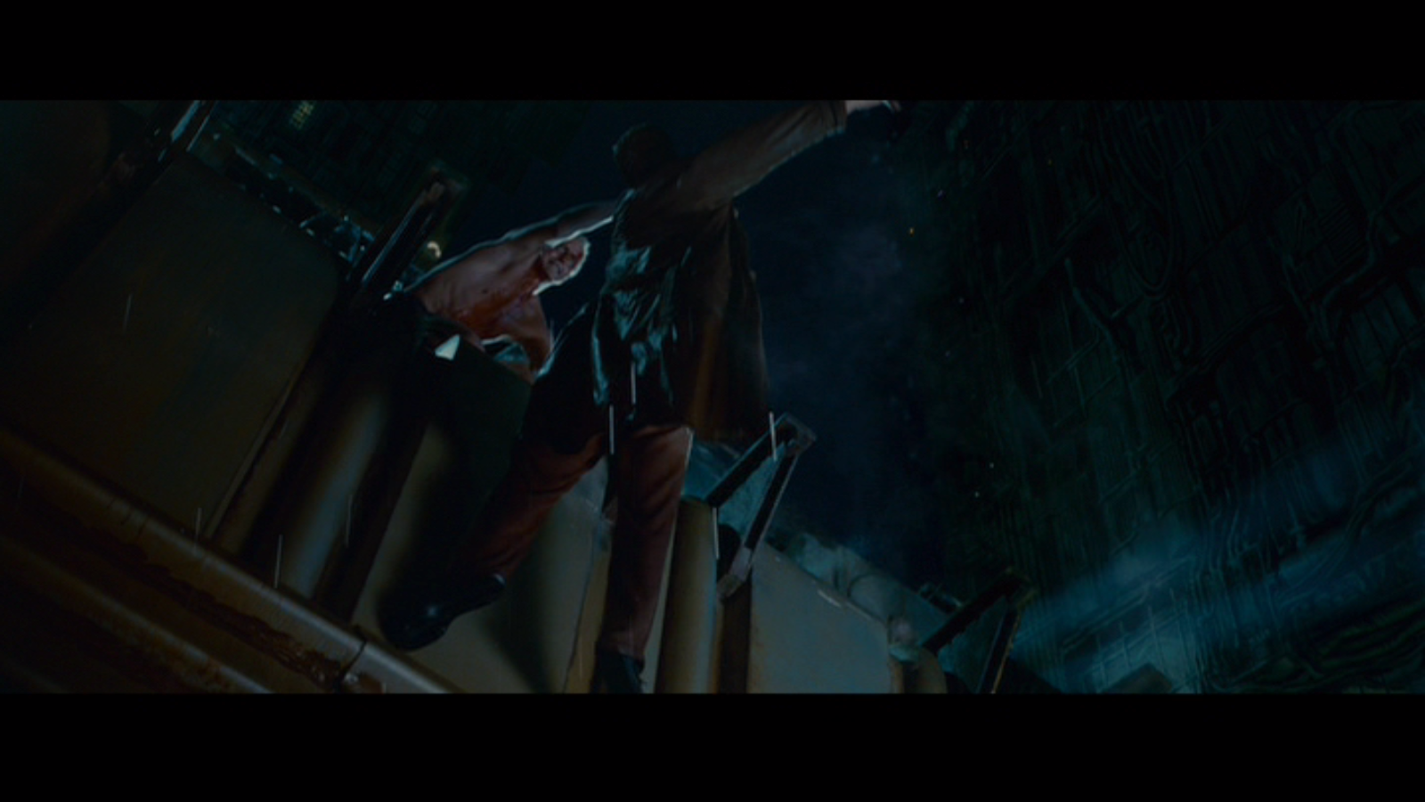

Bryant says he is the best bounty hunter he has ever had, and certainly better than Holden, but every kill is a lucky one. If Zhora had taken his gun or not been interrupted when chocking him, then he wouldn’t have been able to kill her. Leon is killed by Rachael, and Rick had lost the fight before that with him. Pris similarly doesn’t take his gun after beating him up, and then decides the best thing to do is walk to the far side of the room so she can attack him with a somersault, ensuring he has time to get his gun and shoot her. Roy is Deckard’s worst showing, as he gets as many free shots as he likes and still manages to lose. In fact, Roy saves his life, the first life that he hasn’t taken in the entire run of the film.

Deckard is extremely lucky rather than skilled.

So what are we meant to think of him? Except for his acceptance and protection of Rachael, what does he offer? Even that he isn’t particularly successful at, since Gaff still found her and he himself took advantage of her.

Does Rachael’s seeming acceptance of him at the end of the film (and that is somewhat ambiguous seeing as she has no one else) supposed to mirror the audience’s acceptance? There is no clear indication.

These types of unsatisfying ambiguities are part of the enormous difference between Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and Blade Runner.

Just looking at the plot elements of the book and film it might be tempting to say that they are very similar. Character names overlap, and the basic premise of a bounty hunter looking for androids on Earth is the same. Some of the dialogue is taken word for word from the novel, as in Deckard’s interview with Rachael early in the film. But even when it does overlap, the meaning behind the words is different, and the meaning for the respective works is different.

Rachael’s interview in Blade Runner establishes Rachael and Tyrell’s characters, as well as giving us key information about replicants, namely that their memories can be manipulated. Rachael’s interview in Androids sets up the first scenario of mind games being played, and presents to Deckard just how difficult his task his. Although he succeeds in finding out that Rachael is an android, he nearly loses the only method for detecting them because he too easily believed that she could be human.

The Deckard in Androids is also someone we want to root for. He begins the novel an underdog. Bryant establishes that Holden was the top bounty hunter and Deckard had never had to deal with the tough cases that Holden had.

After his interview with Rachael, Deckard realizes how outmatched he is. He feels that he barely made it through an interview with a Nexus-6 type, and he still has to put down six of them, which feels like an overwhelming amount. Another bounty hunter, Phil Resch, puts down 2 of the 6, but Deckard gets the other four due to quick reflexes, intuition, and general skill.

The Deckard in Androids is not only good at his job, but he is contemplative and regretful. After the death of Luba Luft, the android acting as an opera singer, he is the only one to ask what the harm is in letting a beautiful voice like hers remain in the world. He finds Resch’s cold attitude towards the androids disgusting, even as he knows that it is necessary to survive them.

A big deal has been made of whether the Deckard in Blade Runner is a replicant or not, but I have to say the question isn’t particularly interesting because of the forced perspective. If Deckard is a replicant then there is no moral quandary in his actions, and Gaff becomes our de facto hero for letting them go. If Deckard isn’t a replicant, it still doesn’t matter because Blade Runner has been clear on what the right and wrong things to do are. The film has a clear moral scheme, and his decision to save Rachael is correct regardless of what he does.

The question of his humanity obfuscates the real philosophical point, which is this: how do we define that which is human, and how do we treat things that are not?

This is where the Deckard in the book is really important. He is definitively human, and the androids are definitively amoral. Their goal for the book is to see humanity lowered, to see them fall into despair when they show Mercer to be a lie and empathy to be a pointless emotion. They fail because of a fundamental misunderstanding of what it means to be human, but regardless of their success or failure, their goal is a petty one. Rather than trying to lift themselves up, they try to corrupt humanity.

And still, Isidore and Deckard find themselves empathizing and caring about specific androids, even if in the latter case it is only for brief moments. The end of Androids has Rachael killing Deckard’s goat, and he is left with his electric sheep and an electric toad, tired and somewhat devastated, but happy to be done with his task. His wife orders electric flies for the toad and says that her husband is devoted to it. Despite their problems throughout the novel, and despite how demoralizing it is to own an electric animal, both husband and wife are just glad to have each other, to be together. As the world around them crumbles and they are mentally accosted by the petty androids of Buster Friendly and dead animals, they find some sense of warmth in each other’s arms.

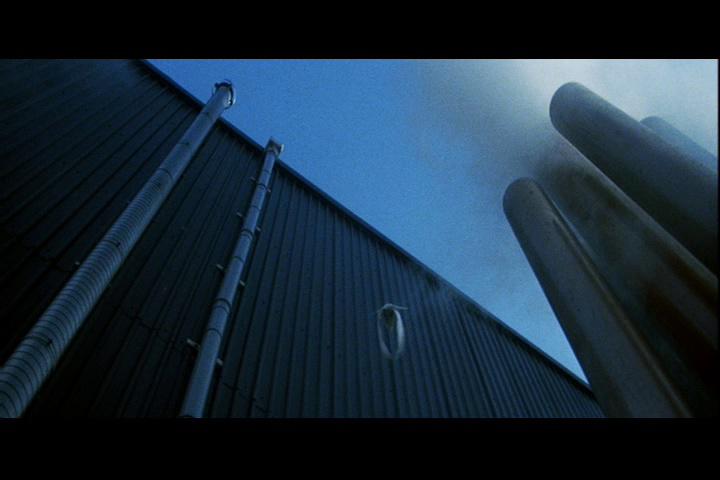

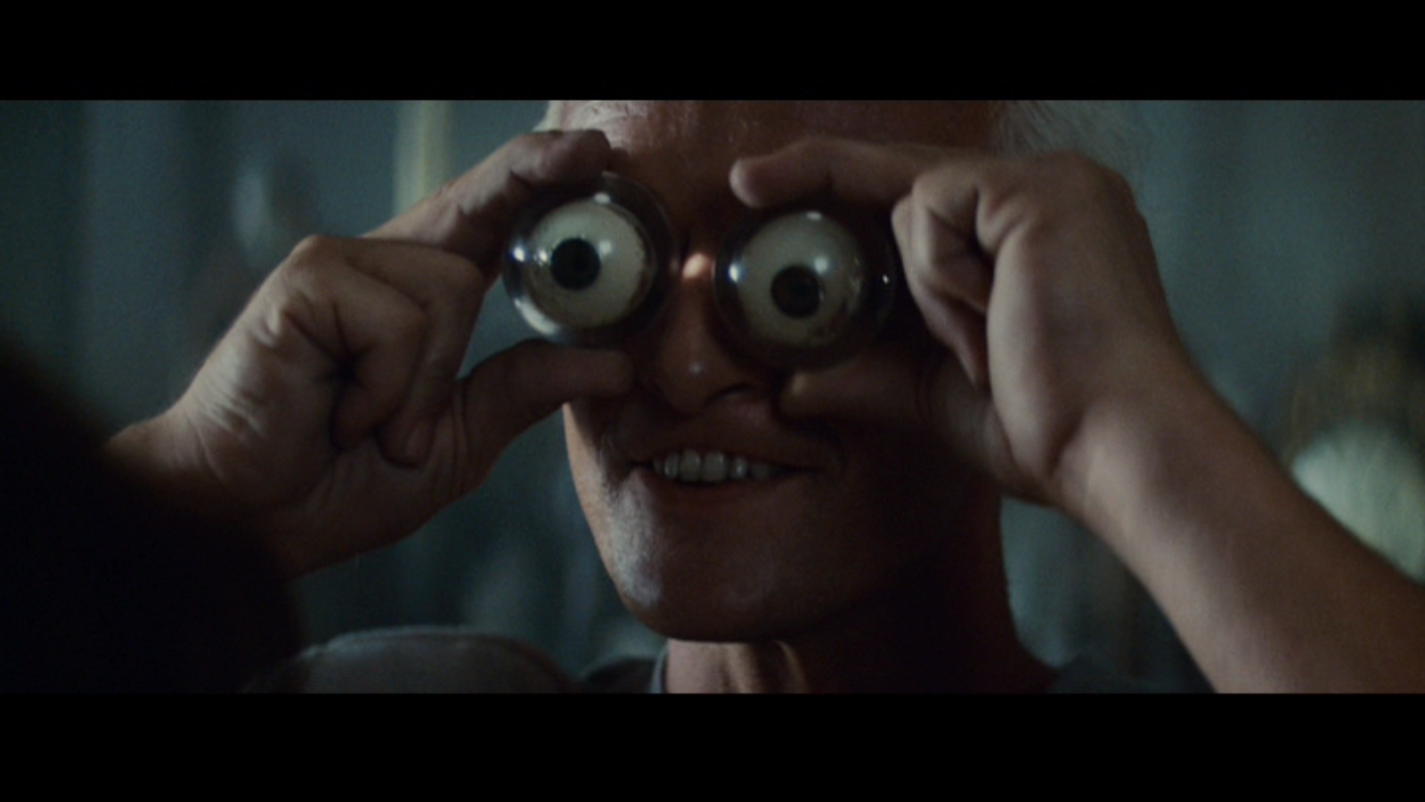

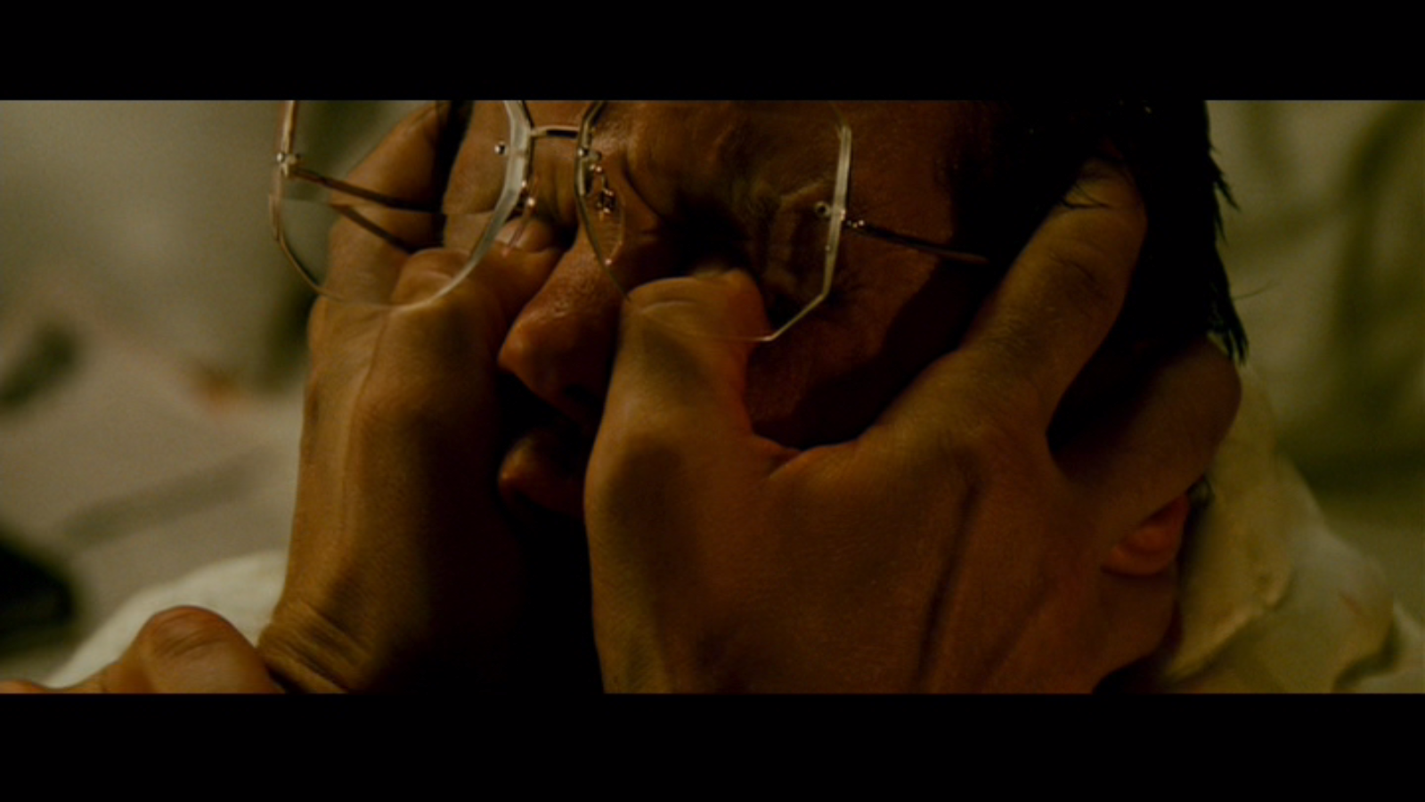

This isn’t to say that Blade Runner doesn’t have corresponding visual motifs, because it does. The most prominent is the focus on eyes. The general darkness of the film makes eye glare much more apparent, but the replicants, and the artificial owl, also have glowing irises in certain scenes.

It’s a visual way to tell that they are artificial. The first scientist that the androids visit, Chew, is the one that works on eyes.

One of the first shots of the film is the fiery cityscape reflected in Dave Holden’s eye as he watches from the Tyrell Corporation.

Roy kills Tyrell in some versions of the film by poking through his eyes, although this was considered too violent for the US Theatrical Cut and the Director’s Cut.

Leon was also going to kill Deckard by poking through his eyes.

Eyes are important for the film, not just in that they represent our weaknesses, but also in that they reflect who we are.

Roy defines himself to Deckard not by his relationships or his actions, but by what he has seen; he is unique and indispensable because no one will see what he has seen. Blade Runner seems to argue for uniqueness by experience. The replicants are important and deserve to be treated as individuals because there is nothing else like them. They have the same potential to do good or bad as the humans do, but they live differently, more fleetingly and desperately.

Like a fingerprint, an iris uniquely identifies a person, and so for Blade Runner the most prevalent theme must be individuality. Whether that be Gaff’s decision to let Rachael go, Roy’s decision to save Deckard despite all of the other replicants trying to kill him, or Deckard falling in love with a replicant, the characters define themselves by their individuality.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is the complete opposite. It values our group mentality above all. Our ability to empathize is the most important trait, and it is what we use to test whether someone is an android or human.

This is best established by Isidore’s decision to connect with Mercer after finding out that Mercer isn’t real. Mercer is supposed to be one of the things that separates the humans from the machines, since they empathize with him whereas the machines cannot. He turns out to be a program, but that just reaffirms the difference between the humans and the machines even more. People just don’t care if Mercer is real because the feeling he provides them is authentic. The book suggests that to be human is to despair, and they all want the feeling of community and unity that they get through his suffering, even if he isn’t a real person.

And yet, authenticity is still very important. No one can tell the difference between a real sheep and a machine sheep, but the owner knows and that is stressful. It’s stressful that their animals aren’t authentic. People desire authenticity even though they can’t get it and they know no one else can either.

In many ways, empathy is a weakness. It allows our protagonist to come dangerously close to sympathizing with the machines and to almost be killed for it, while they couldn’t give less of a damn about him or each other. The androids define themselves in opposition to people, even as people try to make them as human as possible. The Rosen Association’s goal is to make androids indistinguishable from humans, even as the bounty hunters’ goal is to draw a firm line between the two. Humans crave authenticity even as they destroy it.

So Androids defines humanity in its empathy and in its striving for something real which doesn’t exist. The knowledge that it doesn’t exist while continuing to strive for it would suggest existentialism. It’s still individualistic, like the film, as each person has to come to terms with the absurdity of their existence, but that coming to terms manifests itself in Mercerism, in coming together and sharing their feelings and empathy with each other.

Blade Runner is beautiful, and beauty always has value. But that beauty lies in its aesthetics, not its narrative or its characters.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? has a beauty of soul, a desperate yearning for connection and truth in a miserable universe. Living in Blade Runner‘s universe seems fun and expansive with its myriad of different languages jumbled together, its vibrant night life, and fantastic technology. Living in Androids‘ universe is a slog, with every day beating on you and the slow encroachment of entropy visible all around. Its hopefulness and love of its characters are thus all the more cathartic.

Blade Runner

(1968, Philip K. Dick [as Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?]; 1982, Ridley Scott)

Book or film? Book.

Worth reading the book? The book is a psychological dystopia that slowly eats at the fabric of humanism as it makes a virtue of nihilistic hope. It is one of the few sci-fi works that dares to make robots unsympathetic and it asks the right questions about what that means. It is uniquely anti-climactic. If you like sci-fi for the questions it asks, then it is a must read.

Worth watching the film? Possibly. It undoubtedly has historical value, and its cinematography is beautiful. Don’t watch it for the narrative, though.

Is it the best possible adaptation? No. Except for some dialogue and character names, they have very little in common.

Is it of merit in its own right? The Final Cut is stunning, especially on Blu-Ray, and it is always a different experience watching something as opposed to reading about it. But I would say that some of the works it has inspired manage to meld the aesthetic with the narrative better than it has, so I don’t consider it unique anymore.

Note: If you’d like a more detailed look at the differences between versions, this site will do nicely.