When I decided to do these character spotlights, I didn’t give the concept much thought; I just figured they were ways to delay my misery and increase yours for another week. But now, as we near the end, I’m glad I wrote them. They’ve given me a lot of insight into the process of bringing a character to life — how to achieve that and, of course, how not to achieve that — and looking more critically at sitcom characters than the writers ever intended allows you to see the scaffolding.

It’s like that shot of Brian in the opening credits of the first two seasons. We can clearly see a stage light now, but back when the show aired, most televisions would have had a frame obscuring it. As much as I like to joke about the slapdash nature of ALF (ironic since every episode took approximately 12 weeks to shoot), viewers at home wouldn’t have seen that. Now, though, we can focus on more of the frame…and catch a little glimpse of how the show was made.

The character spotlights allow me to do that, too. To drill into details that the writers — in most cases, to their credit, correctly — assume people at home will have forgotten. Alicia Schudt, who is credited with writing three episodes of ALF, commented on my review of “Movin’ Out” to prove the point (with admirable good humor) that I’m recording and remembering details in such a way that allows me to pick up on inconsistencies that someone watching in the late 80s wouldn’t have. It’s the visible stage light all over again; I’m watching it a different way than anyone did at the time. Of course I’ll notice these things.

I see value in that, though. I write, too. (Maybe someday somebody will make fun of all the awful crap I’ve written on their own blog. I’d like to think I’ve written some good stuff, but, I assure you, I’ve definitely written more than my fair share of awful crap.) And knowing what makes a character work or not work — what makes a character a character — is important. It’s also not an exact science, which is why even the failures are constructive. Following the same steps as another writer doesn’t imply in any way that you’ll end up with anything as creatively successful.

The way these spotlights have fallen serves to illustrate that pretty well, and they do so totally unintentionally. We started with Kate, who was — by this show’s standards, at least — a strong and well-enough-defined character from the start. We moved on to Brian who at that point had twice as long to demonstrate his worth, and had shown us nothing. Then we did Lynn (like the mimes we are), who started as nothing, and then became something. Sure, she later settled into a kind of wasted neutrality, but there was a process of gradual characterization there that meant it was good that we waited to analyze her.

And now it’s time to strip Willie down and see what we find.

Willie, who has the benefit of being spotlighted after the final episode. In theory I could have written at length about a character before, only to have them prove me wrong in every subsequent week, or experience some sort of profound evolution that would render my entire spotlight inaccurate. But Willie…well, we’ve seen all of Willie. We know Willie best of all of them. Or…we should. He’s certainly had more screentime than any other human character on the show.

By now, we shouldn’t even need a spotlight. Right? You’ve all been reading about him for 99 episodes straight. Don’t you know who Willie is?

Clearly I’m being rhetorical. Willie is nobody. He’s nothing. He’s there, but he’s undefined. At least…for the most part.

See, all of these characters were undefined. That’s what happens when the writing is inconsistent. It falls to the actors to figure out who these people are, which is why Anne Schedeen, as Kate, shined so quickly and completely; she had a handle on Kate. The frustration that that character would feel with someone like ALF in the house — wrecking shit up, demanding her time and attention, endangering her family — was something Schedeen recognized and understood how to channel. As a result, Kate wasn’t just a name written next to some lines on a script. She was a character.

Andrea Elson — our easy runner up — initially portrayed Lynn as a name written next to some lines on a script…but eventually got the chance to tap into her natural warmth (most notably in season two) and immediately improved as an actor as a result. I doubt it was intentional or even necessarily the result of any hard work on her part, but once she “understood” something about Lynn, it made a big difference. Again, she was rarely great, but she absolutely grew, and the change was notable.

Benji Gregory was a kid. Yeah, I give him guff, but that’s because I sometimes like to tell jokes for you. In reality, he was just some child actor in the only job he’d ever have. He was shitty, but so are all child actors, except for that girl in Kick-Ass. Gregory — and, as a result, Brian — never grew because he was trapped on ALF and there was nobody there to help him grow, to teach him to grow, to coach him and guide him in any aspect of his performance. He’d read a line, and they’d shove him aside to reset the puppet trenches. Maybe he scratched his armpit during the reading. Maybe he was looking at the wrong character. Maybe he mispronounced or failed to emphasize the only important thing he had to say. It didn’t matter. They took whatever they got and moved on. How could the kid grow?

Then there’s Max Wright. Each of these characters were vague shells at best. Maybe they’d have the same desires or interests from one week to the next, but normally they wouldn’t. It was up to the actors to provide them with some kind of consistent voice and presence. Some kind of characterization. So Max Wright provided Willie with the only thing I’ll ever remember about Willie: the fact that he was a complete fucking asshole.

He wasn’t supposed to be, of course. Hell, he was a social worker. He was a provider. He sheltered ALF. He provided exposition, transportation, financial consideration, or whatever else that week’s plot needed to get moving. But Max Wright proved how drastically a performance could affect the way a character is perceived and remembered. And he proved it by being a complete fucking asshole.

Wright’s personal concerns — to put it with supreme diplomacy — about ALF are well documented. While everybody involved hated the show, and each walked separately into the sea never to be seen again once they finished shooting it, Max Wright took his hatred to impressive levels. He verbally abused the crew, physically assaulted the puppet, stormed off after his final scene in “Consider Me Gone” without saying goodbye or even allowing a second take, and vented his frustrations by picking up homeless people for a crack ‘n’ blowjob jubilee.

I mean, yeah, I hate ALF, too, but even I think he took that a little too far.

And his (at least partially justified) dickishness bled through to the character. We already saw his interests and hobbies shifting on a weekly basis, and it took the better part of a season for the show to decide what the hell he did for a living, so it had to be up to the actor to give the character a distinctive personality. (Theory: the reason people who watched this show as kids don’t remember any of the human characters is that none of them had distinctive personalities. Second theory: that isn’t a theory.)

By default, then, that character became a complete fucking asshole.

Max Wright’s performance took the writers’ worst tendencies and threw them into sharper relief. It emphasized the bad things they wrote into the character and made any good ones ring false. Their carelessness looked almost calculated. Willie’s flaws seemed less like sloppy writing and more like deliberate characterization. Wright’s dickishness, in short, filled in the blanks, and made the character seem worse than he otherwise would have.

Whenever I mention Willie’s shitty personality here and people push back, I know that what they’re really saying is that he’s not supposed to be an asshole. That no matter what the character says or does, we’re not supposed to think of him that way. They’re claiming that that’s not the intention of the character.

And they’re right.

Which is why Willie Tanner isn’t a character at all; he’s a fascinating intersection of poor writing and awful acting. Willie is a character that’s been so carelessly assembled that there’s no way for the show to keep him in check. No matter what he was supposed to be…he’s something else entirely now, and there’s no getting him back.

We’ve seen that before. It’s sometimes charming, and you end up with The Room, in all of its hypnotic, ramshackle glory. But with ALF, you just end up with a sentient ballsack.

Willie is supposed to be a normal guy. An average joe. Maybe slightly nerdy or socially awkward, but he’s meant to be a standard straight man. A sitcom dad who doesn’t always do the right thing, but has his heart in the right place. Wright’s performance, though, causes those aspects of the character to feel hollow and forced, and makes his flashes of assholishness — which are surprisingly frequent — feel genuine, simply because that’s what comes from a genuine place.

And, unfortunately for ALF, that’s how the character ends up being defined…not by what we’re told, but by what we observe.

That’s…a lot like real life, actually. It’s why when a presidential candidate gets stumped by an interviewer, we take away from the experience that he or she is unprepared for the job; the candidate claims to be prepared, but we’ve now seen otherwise. It’s why we all have friends or colleagues who talk about some selfless thing they did and we have to roll our eyes, because we know they aren’t selfless people, and just performed whatever minor gesture was necessary so that they’d have something to pat themselves on the backs for. Hell, it’s why we buy property from Ricky Roma and not from Shelly “The Machine” Levine.

Anyone can tell us anything…but it’s what we see, what we perceive, what we already know that shapes our perception.

We can, and do, separate what people tell us from what they show us, and we can do this with Willie. In fact, it’s probably a good exercise.

The show wants us to see Willie as a normal, relateable, well-meaning guy. That’s what it tells us he is, over and over again. But what do we actually see through his relationships with others? Does he say he’s compassionate, or does he demonstrate compassion? Does he say he understands, or does he demonstrate understanding? Does he say he cares, or does he show us his caring nature?

By their fruits, ye shall know them. So let’s get our lips around Willie’s withered old fruits.

His Family:

No, not the Tanners we know. We’ll get to them. For now, let’s talk about the Tanners we oddly don’t know: the ones Willie grew up around.

What’s his father’s name? His mother’s name? What did they do for a living? Are they alive or dead? The fact that we don’t know any of this, or anything else, is alarming, especially since we spent a number of episodes exploring Kate’s upbringing and relationships with her parents. Less so her father, for sure, but at least we knew the guy’s name and that he died. Willie never shared his parents’ equivalent information.

The fact that Willie never talks about them implies a kind of distance, and the fact that we never got an explanation for that distance implies that he doesn’t really care, or that he’s perfectly fine without them. (Compare to Jake, who also never talked about his mother…until we got an entire episode explaining exactly why that was, and which characterized and humanized them both in the process.)

Willie comes off as detached in general, manifesting itself as a complete disinterest in everybody he grew up with.

It gets even odder when we meet Neal, because we were told in “Night Train” that Willie had one sibling, and in “La Cuckaracha” that that sibling’s name was Rodney. When we meet Neal, it either implies that Willie forgot he existed, or that he had at least one sibling he deliberately cut out of his life and chose to never speak of. Either is believable. And let’s not forget that in Neal’s introduction (“He Ain’t Heavy, He’s Willie’s Brother”) Willie — whose occupation centers around helping people — opens the episode already bitchy and frustrated that his brother needs his help.

In “We’re So Sorry, Uncle Albert” we meet one of Willie’s uncles, who evidently was kind of a shit at some point but is super nice now. He drops dead on Willie’s property and Willie doesn’t seem to care. In “Mr. Sandman” we learn about Aunt Pat and Great Grandpa Silas, just in time to reveal that they’ve both been dead for some indeterminate number of years, which is good, because that means Willie never has to think or talk about them, either.

Family goes a long way toward shaping who we are. Great works in all media (The Sound and the Fury, The Royal Tenenbaums, Arrested Development) have been obsessed with that notion in both deeply dramatic and powerfully comic ways. It defines us. If it doesn’t define us, the gulf between us and our families defines us. It’s woven into our DNA in more ways than simple genetics.

But Willie isn’t there for his family, unless they force him to be there by pulling into his driveway in a Winnebago. He never speaks of them, which means we can’t conclude that the separation is a necessary thing on Willie’s part, as we were able to with Jake. And he doesn’t even seem to remember they exist until he hears that they’ve died, at which point he doesn’t reminisce about them but rather starts pawing through their possessions.

He tells us nothing, which wouldn’t on its own reflect poorly on him…but there’s a lot more of this spotlight to go.

His Colleagues:

For whatever reason, Willie’s family isn’t all that important to him. But maybe it just seems that way because he doesn’t see them often. What about the people his interacts with on a daily basis?

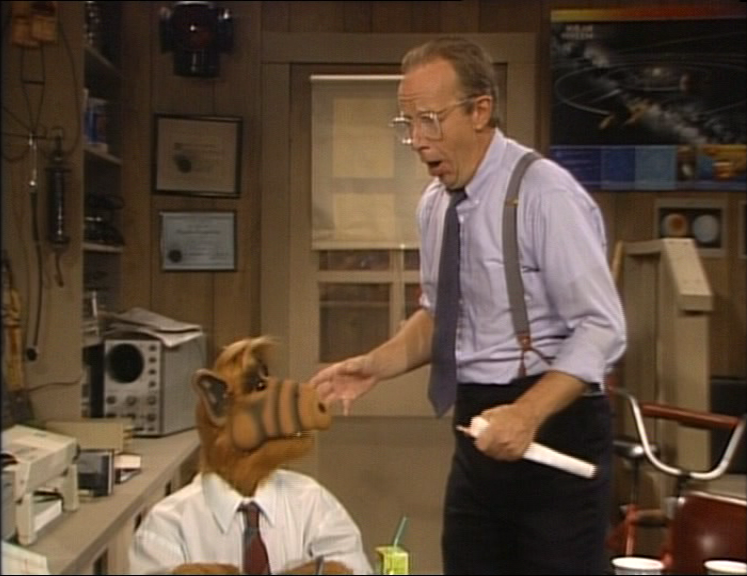

Well, we can answer that. Every so often, we do see Willie at work, but we’ve never seen him interacting with the same person twice. Shit, both times we saw his boss (“Border Song” and “Some Enchanted Evening”) it was a different guy. So, once again, it’s impossible to see Willie as having formed any lasting bonds with any-fucking-body he’s ever met.

The few times we do see him interact with them, or hear about his interactions with them, Willie doesn’t come off well. We had our longest sustained look at this in “Movin’ Out,” in which he bitched about having to do the work that he was specifically hired to do, as a result of a promotion that he specifically angled to get, and was rude to colleagues who were struggling hard to do their jobs, with limited resources and a complaining bozo for a boss. In “Mind Games” he even complained about a coworker to Dr. Dykstra…because that coworker was, y’know, helping lots of people and doing great work that earned recognition. That sure ruffled Willie’s feathers.

And then there’s Jimbo from “Hide Away.” A colleague who just needed a friend, was clearly suffering, and certainly never did anything wrong, but Willie just sat around giving the guy the stinkeye, making fun of his poverty and loneliness, and acting put out about having to deal with him at all.

Maybe we just catch him on bad days, though, right? Maybe his colleagues have a better view of his behavior than we do.

And, hey, they do! So we can turn to “It’s My Party,” in which his coworkers have to actively guilt him into inviting them to his luau. Why? Because he never invites them anywhere or does anything for them. Bad enough, but here’s why that’s a problem: they evidently do favors and nice things for him, from driving him around when his car is being repaired to throwing him parties on his birthday.

In return, he leaves every day at 4 o’clock with both middle fingers in the air and “Go fuck yourselves” on his lips.

This is Willie.

Those in Need:

Oh, and, hey, speaking of his job…what is it he does for a living, again? Some kind of barber?

Wait, no…it’s social worker, right? You know. One of those people who are there to help the less fortunate navigate their emotions, their crippling poverty, their ineffably sad and difficult existences? Well, Willie — as often as we hear about him receiving raises and promotions — tries to accomplish this in “Movin’ Out” by insulting a woman on the phone who can’t afford to feed her starving children…a problem caused directly by Willie’s incompetence.

I’ve said many times that Willie isn’t a social worker, as much as the show would love us to believe he is. Whether at work or in his personal time, the guy doesn’t act like a social worker. He cares about nobody other than himself, and seems to be the first person to throw up his hands and say “Not it!” whenever somebody needs help.

Seriously. In addition to his conversation with the woman I just mentioned — someone that it is his job to help, and someone who now has no money for food because Willie didn’t do his job — look at how he deals with others in need.

In “We Gotta Get Out of This Place,” Jodie — a blind friend of the family — is evicted from her apartment and has nowhere to go. Willie has no reason to turn her away, except that he’s an asshole, so that’s what he tries to do. In “Hungry Like the Wolf,” Willie hears a woman, a girl, or a dog (or some combination; it’s not clear) get hit by a car outside of his house, and he not only refuses to help them, but stops his wife from helping them.

And the homeless? Oh, the homeless…

In “Night Train” he watches a hobo jump to his death and doesn’t so much as shrug. In “Hungry Like the Wolf,” again, he ridicules and ignores a homeless man he meets in the park. And in “Turkey in the Straw” Willie demands his clothes back from Flakey Pete and kicks him out into a rainstorm…after arming himself to bash the guy’s head in if he didn’t cooperate.

The latter is especially unnerving, since Flakey Pete was polite, engaged Willie in conversation about a mutual hobby, and was no threat whatsoever. It’s Willie’s job to show compassion, but he never seems to show even basic humanity, taking back clothes he didn’t need and kicking the hobo out of a garage he wasn’t using.

The best part? In “ALF’s Special Christmas” we learned that when Willie was little, his family was homeless. Kindly Mr. Foley took them in, and that was one of little Willie’s most cherished memories. A man who owed the family nothing saw their plight, and welcomed them into his home. Willie looks back on that with fondness, but no self-awareness whatsoever as he continually kicks others while they’re down.

This is to say nothing of situations like ALF’s cotton ball addiction in “Hooked on a Feeling,” which is something Willie should not only be prepared for as a social worker, but should deal with every week of his career. For him to act like there’s nothing he can do to help ALF — and to insult his family when they suggest they should help ALF — just raises, again, the question of why the show made him a social worker in the first place.

It’s a sitcom. You’ll have situations like this every week. Why give Willie that job if he’s not the one who is going to deal with any of the problems that arise? This would be like creating a sitcom in which the father is a firefighter, and every week the kitchen is set ablaze while he acts like he doesn’t know what to do, and leaves his family to deal with it.

You could conclude a lot of things about that character, but you certainly wouldn’t see him as a good guy.

Crack:

WILLIE SMOKES CRACK

His Wife:

We’re told that Willie loves his wife. Which is great, because I never would have guessed that from his behavior.

When they share a couch or a bed, they don’t touch. They read separate books or face different walls. He doesn’t act like he’s fond of her, or even like he cares much about her. Compared to the Ochmoneks — who are always touching, laughing together, taking daytrips — it’s clear that Willie and Kate are not in love. They don’t even act like friends.

More specifically, he insults her education and her interests in “Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark,” is rudely dismissive of her supportive comments to Neal at the end of “Love on the Rocks” (“I just expressed that, honey”), and refuses to help her with groceries or housework while she’s pregnant with Eric, culminating in ignoring her outright when she tearfully pleads with him to get ALF out of the room in “Having My Baby.”

Of course, maybe he treats her like shit but at least appreciates that he landed a woman way out of his league. Right?

Nah. In “Don’t It Make Your Brown Eyes Blue?” he laughed himself hoarse over the idea that anyone would find his hideous shrewhag of a wife attractive in any way, and made sure she knew what a ridiculous concept that was.

Furthermore, he blamed her for his own emotional hangups about Lynn having sex (“I Gotta Be Me”), ridiculed her suggestion to help a family member struggling with addiction (“Hooked on a Feeling”), and literally left her to be torn apart by a wild animal (“Hungry Like the Wolf”).

Come to think of it, this season provided Kate with plenty of opportunity to reconsider her marriage, as Willie ruined her birthday party in “We’re in the Money,” didn’t do anything for their anniversary in “Gimme That Old Time Religion,” and then forgot Valentine’s Day a couple of weeks later in “When I’m Sixty-Four.” In the case of their anniversary he gave up on trying to find a gift for her, because that would mean he’d have to pay his wife some kind of attention or something. In the case of Valentine’s Day he was at least gracious enough to take her out for a Whopper Jr.

His Kids:

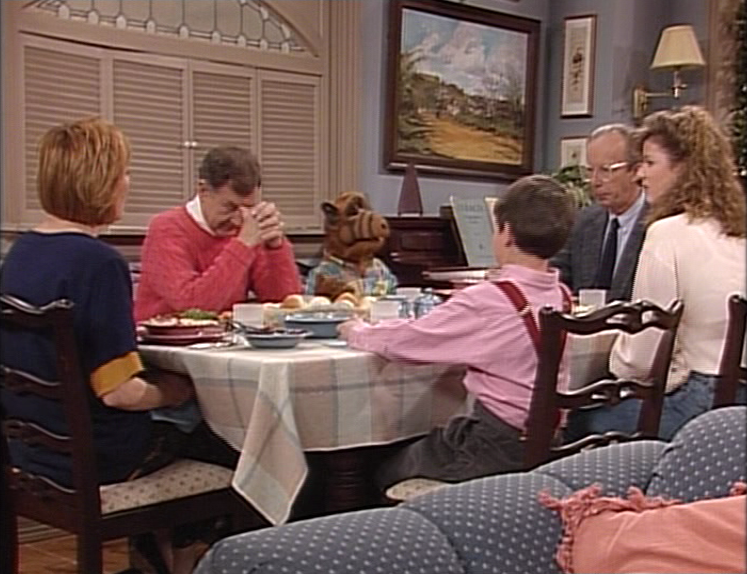

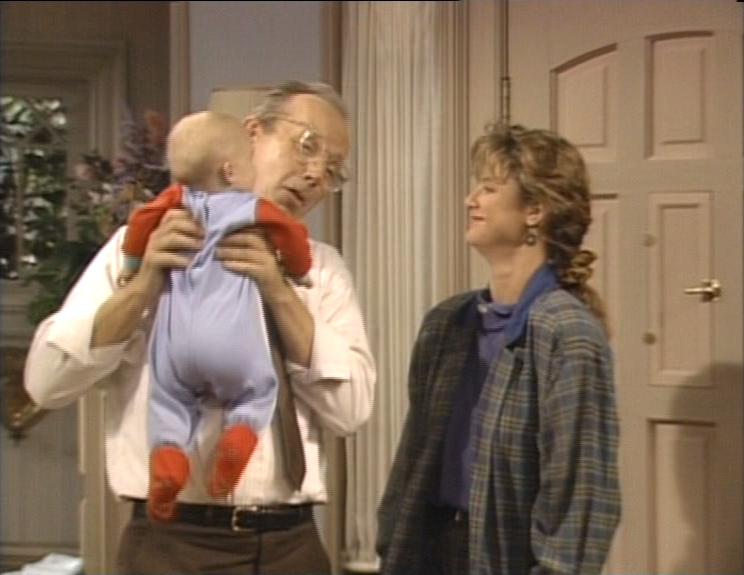

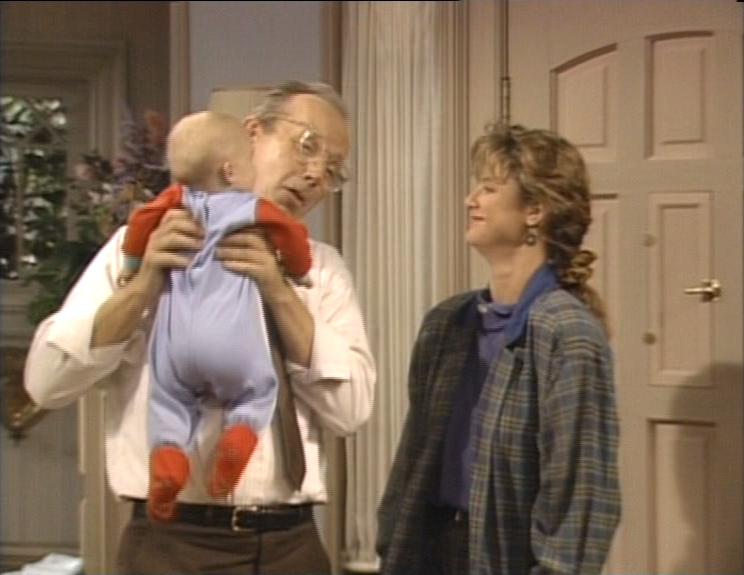

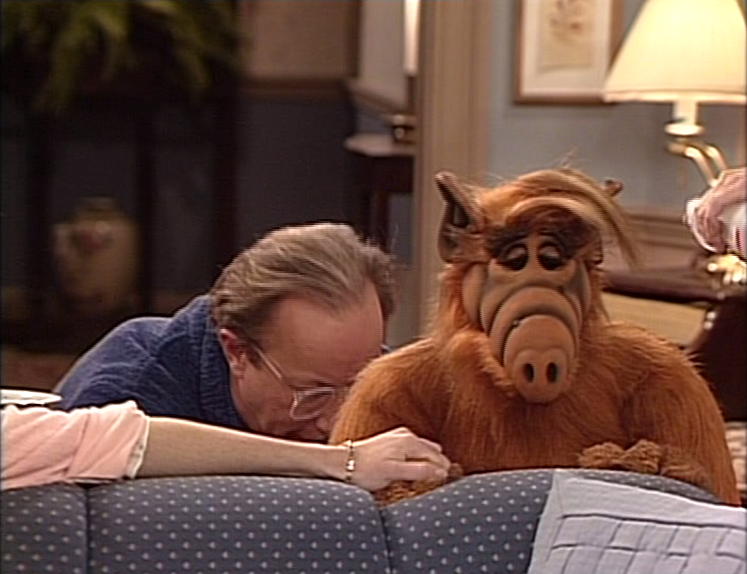

Man, can I just point out how hard it is to find pictures of Willie with the people I’m talking about? Like, he has plenty of scenes with them, but there are slim pickings when it comes to screengrabs he shares with them. Which is probably another reason Willie seems to be so detached from everyone else. Kind of an unintentional mirror of the way McMurphy and Nurse Ratched were deliberately not framed together in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, to emphasize their opposing viewpoints.

Anyway, Willie hates his fucking kids.

At least, I assume he does, based on how little time he spends with them, and how disinterested he seems to be in anything that’s happening in their lives.

Like, seriously. I am hard-pressed to think of any examples of times Willie demonstrated that he gave half a shit about either of them. (Eric doesn’t count. Nobody gave half a shit about him.) I guess he took Brian to Little League in “Lies.” In “Oh, Pretty Woman” he tried for about four seconds to convince Lynn that she wasn’t hideous beyond redemption like her mother.

And…

…what else?

This is a family sitcom. About a family. In which the family rarely interacts or has anything to do with each other. He’s their father for shit’s sake…and how often does he actually act like one? The rest of the time — including when he finds out that his daughter is being preyed upon by someone in a position of authority in “True Colors” — he couldn’t possibly care less.

The odd exception here? Jake.

Willie seems to like Jake. In fact, the few times they interact he appears to be genuinely fond of him. He’s welcoming to him, he kids around with him, and he demonstrates interest in what’s happening in his life. You know. Like you might expect him to do with his own son.

This is especially evident in “Fight Back,” when they bond over automotive repair, but it manifests itself in much smaller ways throughout the show, such as when Willie seems to have actually missed him in “Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow.”

I honestly do wonder if Willie and Jake developed more of a relationship in the fabled Monday scripts — the drafts that were evidently pretty good until Paul Fusco got his hands on them and crossed out every word that wasn’t “ALF” — but we’ll never know for sure.

Either way, we do know that whenever Jake does come over, Willie uses it as an excuse to remind his kids that he likes the neighbor boy much, much better.

His Friends:

jk

Willie has no friends, which is crazy to me. Take some time to list any principal sitcom characters you can think of that don’t have any friends. While in some cases that might be framed as a joke — or a way to characterize that person as a curmudgeon — I can’t think of one example of a character who has associated in literally no friendly way with literally anybody throughout the entire literal course of a series.

And yet: Willie.

Kate keeps in touch with some old college friends, as we saw in “Tequila.” She also seemed to be on friendly terms with a colleague at the real estate office in “Changes.” Lynn had Julie, who we never met, and then Joanie, who we met in “Live and Let Die,” likely because the writers forgot her name used to be Julie. She was also friends with Randy, who first appeared in “Promises, Promises” and was so dumb he didn’t realize that you didn’t need to be nice to Lynn if you wanted to sleep with her.

And Brian? Yeah…even Brian. He became friendly with Spencer, the world’s weediest excuse for a bully, in “It Isn’t Easy…Bein’ Green,” and had honest to goodness friends in “Stairway to Heaven.” Okay, the latter was a fantasy sequence, but if it weren’t for fantasy sequences this kid would have no reason to get out of bed in the morning, so let him have that.

Shit, even ALF had friends. Loads of them. Like, more friends than I’d ever even want, despite the premise of the show being that ALF is a secret and can never, under any circumstances, meet anyone.

But Willie?

Willie associates with nobody. When Jimbo or Flakey Pete or Mr. Ochmonek or anybody else tries to engage him in conversation, Willie takes it as a personal insult that they’d think he’d deign to spend time with them. He’s not interested in getting to know anybody. In “Someone to Watch Over Me” he’s surrounded by neighbors he doesn’t know or care to know. He’s put out, in fact, by their request that he help the Neighborhood Watch…in spite of the fact that the Neighborhood Watch is there to keep him safe as well. (Those selfish damn social workers!)

The closest thing to a friend he had was Dr. Dykstra, who we met in “Going Out of My Head Over You.” There Dr. Dykstra seemed pleased and surprised to see Willie, implying that it’s been a long time since he’s heard from him. Sure enough, Willie’s only there because he needs something. And if you think I’m being too harsh, skip ahead to the good doctor’s final appearance in “Mind Games,” when Willie’s done with his services so he thanks the guy for his unpaid work and forced secrecy by calling him an irritating nuisance. Some friend.

The next closest thing he has to a friend? The Ochmoneks, oddly enough, who he repays for their kindness by making fun of them constantly, being rude to them, refusing to help them, refusing to thank them for the help they provide him, and just genuinely being an all-around fuckbag at every opportunity.

It’s implied in “Turkey in the Straw” that the families have known each other since Lynn was a child…at least a decade, then. Yet by the time of “Come Fly With Me,” Willie hadn’t even known Mr. Ochmonek was in the Korean War, which shows just how much interest he’s ever shown in the guy.

And that’s it. Even Willie’s friends aren’t his friends.

Well, with one exception, maybe…

ALF:

ALF and Willie aren’t friends. They’re also not enemies, however often they may seem to be. (That’s down to the actors hating each other in real life, a friction that makes watching ALF pretty fascinating when you keep it in mind.) They’re…some combination of “friend” and “enemy.” If only we had a word that ties both extremes into one. I’d like to propose “enemiends.”

I’ve gone back and forth on whether ALF and Willie or ALF and Brian should have been the core relationship of the show. Frankly, either could have worked in deft hands with stronger writing. But ALF and Willie seems like it would be the more fruitful choice…especially since this show, as bereft of creativity as it was, still managed to do some interesting things with their dynamic. Brian, by contrast, was never more than an afterthought, no matter how much he might have been conceived of as a sitcom version of Elliott from E.T. (The crucial difference here: Elliott gave some shits.)

But ALF and Willie have a relationship, at least. And that’s something the latter has with nobody else. Not his coworkers, not his kids, not his neighbors, not his parents, not his brother, and not even his wife. Willie connects to nobody. E.M. Forster wrote a two-word epigraph for Howards End: “Only connect…” One imagines that the epigraph to Willie’s autobiography would be “Please leave.”

ALF gets in, though. ALF, oddly, matters to him. I don’t need to cite examples of the times Willie is drafted into ALF’s schemes, responsible for rescuing ALF, enabling ALF’s flights of fancy, opening up to ALF, playing games with ALF, arguing with ALF…

It’s not a well-drawn relationship, but it’s certainly a rounded one. Willie and ALF have their ups and downs. They share laughter and they get on each other’s nerves. They understand each other, even if they don’t necessarily agree with or like each other. They know each other.

Which means something.

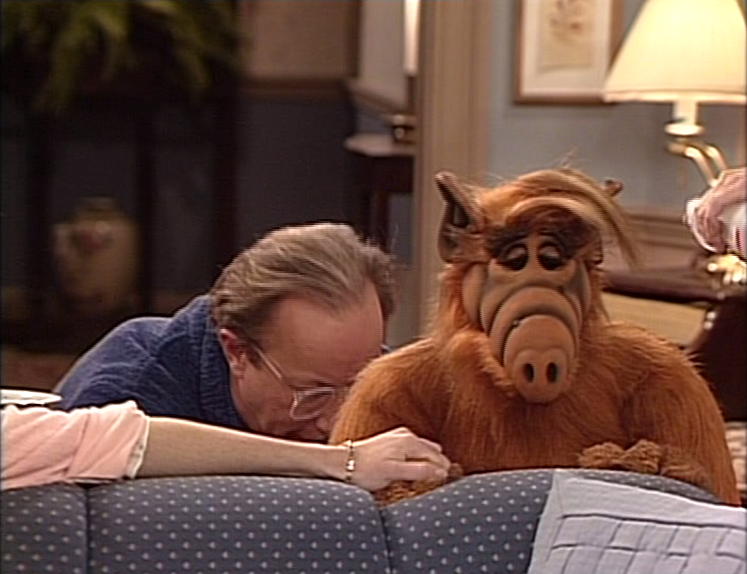

Sure, the show never let it mean anything interesting (at least not for long) but it bubbled to the surface anyway. By sheer virtue of these two sharing screentime as often as they did — notice how I had no trouble finding screengrabs of he and ALF together — a relationship was built, suggested, explored passively. It may have went nowhere, but at least it started somewhere.

And that’s what makes it odd that by the very end, “Consider Me Gone,” Willie couldn’t muster up the interest in a proper goodbye. Oh, sure, he was at ALF’s farewell party, and he gave a speech of the exact same degree of shitness that everyone else gave, but he was still miserable. Not miserable that ALF was leaving, but miserable because that’s who he always had been and always will be, regardless of who surrounds him, regardless of where he is in his life, regardless of how much he has or does not have.

He had no relationships with anybody, until he finally developed one with ALF. Which would be heartwarming in some hypothetical way if it weren’t for the fact that it meant absolutely nothing to him, and he is just as happy to see it go. (For hilarious contrast, watch the opening of Pee-Wee’s Big Holiday, which sees Pee-Wee’s hypothetical farewell to an alien friend we never even got to meet. That’s how you convey a parting that’s important to a character without necessarily having to develop that importance in the longterm.)

For the first and last time, someone had a relationship with Willie. And ALF ends with that someone being bayoneted in a field while Willie watches on, shaking his head when he hears his friend’s cries for help.

Sorry. “Friend.”

And that’s Willie. Not what we’re told about Willie, but what we actually see of Willie.

A complete fucking asshole.

Were there no examples running counter to what we’ve listed above? Of course there were.

Were they anywhere near as believable coming from Max Wright? Of course they were not.

Wright, for better or for worse, is the actor who brought Willie Tanner to life. As a result, we’ve spent four years with one of sitcom history’s most consistently miserable dicks.

But, hey, you’re free now, Max. ALF is over, and the big, bad puppet man will never bother you again.

You’ve got your career back, just like you wanted, and now you can land those choice roles and show the world exactly what you’ve got to offer.

Right, Max?

…Max?