I probably pushed most of the Mega Man fans away when I said I actually wasn’t all that keen on Mega Man 3, and I’ll push the rest of them away by saying that I absolutely love Mega Man 4. It’s a truly wonderful game, and one of the best in the series. That’s not a popular view, I know, and it’s one that I was surprised to arrive at myself.

A few years ago I was speaking to a friend of mine about the series, and he said that Mega Man 4 was his favorite. I was…shocked, to say the least. For starters, the answer to that question is Mega Man 2. This is not up for debate. But for him to pick a game that wasn’t part of the initial celebrated trilogy? That was just…madness.

Only it kind of wasn’t, and my surprise was a result of the game’s reputation, not its quality.

The annual release of Mega Man games had — at exactly this point — started to grate on people. It made the series feel cheaper and more disposable than it actually was. Each game still represented an experience worth having, but the games felt formulaic. While it might have been fun to fight a bunch of colorful robots and steal their weapons, was every new batch of colorful robots as fun to fight? Would all of the weapons be worth stealing?

Mega Man fans experienced a kind of series fatigue around the time of Mega Man 4, possibly only because it proved that it wasn’t just the first few games that would be released in a cluster; Mega Man was going to keep getting duped by Dr. Wily every year for the foreseeable future. That made our hero look like an idiot, and made us less likely to invest our efforts in helping him succeed. If Dr. Wily is just going to be back again in a few months, why bother? If this batch of Robot Masters doesn’t look especially interesting, why not just wait for the next one? God knows it won’t be long…

When my friend said he loved Mega Man 4, I couldn’t believe it. Wasn’t the series legendarily tired by that point? Wasn’t it just dragging its carcass around until Capcom finally put it out of its misery? When I announced this series of writeups on the Noiseless Chatter Facebook page, fan Dylan commented, “Isn’t 4-8 ‘Then they just phoned this one in’?”

That’s the air of muddy disinterest that surrounds Mega Man’s middle period. And that’s unfortunate. Not only because there’s still a lot of life in Mega Man 4, but because this game actually deserves the reputation that Mega Man 3 has.

Oh yes.

I mean that.

This is the near-masterpiece everyone thought they were playing last time.

My friend may have surprised me, but he inspired me to revisit the game with fresh eyes. With an open mind. With a willingness to engage that I guess I just didn’t have before.

It was my loss.

Mega Man 4 is incredible.

I don’t mean that it’s flawless, of course. I don’t even mean that everyone who reads this and gives the game another shot will agree with me.

I just mean that it’s a game that’s stuck in the cultural consciousness as one thing, when it should, by all rights, be remembered as another. It was the last game that successfully advanced the Mega Man formula, and arguably the last one that successfully honed — as opposed to merely tampered with — what came before.

It’s a smooth, fun, surprisingly enjoyable adventure that does not deserve to be remembered as the point at which the series went downhill. I assure you, it was not.

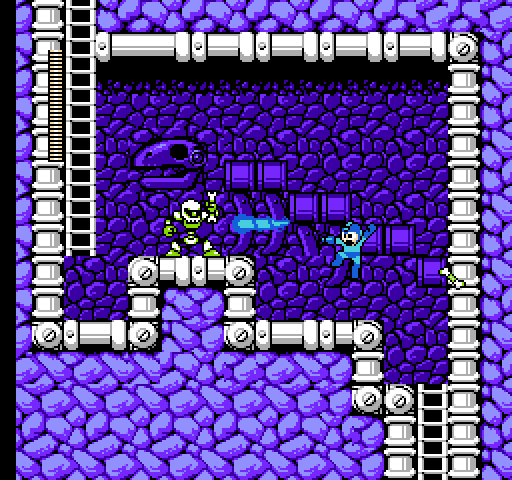

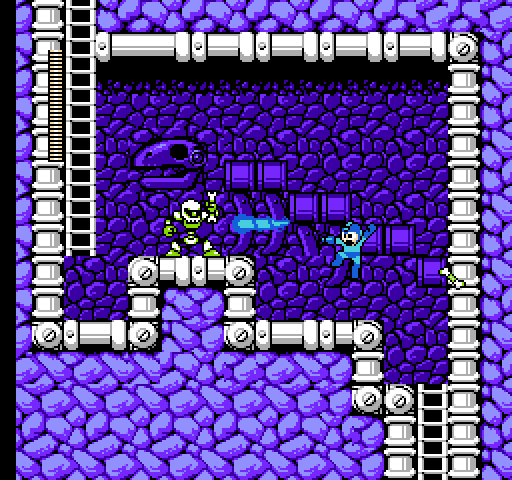

Mega Man 4 does a lot of things exactly right. As much as it gets dismissed, it was last game to make any lasting tweak to Mega Man’s standard moveset: the ability to charge Buster shots. This remained a staple of the Blue Bomber’s loadout until Mega Man 9 very deliberately pressed the reset button, and it even carried forward to spinoff series like Mega Man X and Mega Man Zero. (The slide, by contrast, did not, replaced by a similar but distinct dash mechanic.)

The chargeable Buster isn’t universally embraced, and I think that’s fair. I personally like it, but I also find myself not using it much.

Holding B will power up your shot by several degrees. Letting go of B unleashes whatever power you’ve built up. It can devastate minor enemies and can do a decent chunk of damage to bosses as well, but maneuvering in a game series as tricky as Mega Man is difficult enough; having to hold down a button while navigating disappearing blocks, hopping through projectiles, or carefully managing jump height to avoid spikes adds an additional layer of challenge that may not be worth the enhanced firepower.

I remember using the charge shot a lot as a kid. As in, almost always. As in, every stage’s soundtrack had its distinctive, bright hum overtop of it. Now I use it very rarely, and mainly for the few enemies that require it. But I do appreciate it, and it introduces additional layers of on-the-fly problem solving that benefit the game.

First, there’s the hit that you take to maneuverability in exchange for firepower, which makes more urgent the fundamental question of any Mega Man game: can I stay alive long enough to beat these foes? If you can’t move as gracefully, you’ll take more damage…but you’ll also, potentially, do more damage. Every new situation requires this issue to be reviewed afresh, and Mega Man stages are rife with varied situations.

There’s also the simple matter of time it takes to build up a shot. Is it worth pausing in a firefight to charge up your weapon? Maybe…but then again, maybe it’s better to shoot a number of smaller, weaker shots instead.

And what about the difference in precision? If you only have one charged Buster shot, can you be sure you’ll hit your target? The uncharged Buster is weaker, but you can fire many more shots in the time it takes to charge just one. Are you good at hitting your targets, or are you more successful when you pepper the screen and hope for the best?

The chargeable Buster is an innovation that works, because it forces players to think of the standard Mega Man formula in a new way without actively working against it. If you don’t like the chargeable Buster, it’s possible to play Mega Man 4 without it. Sure, you’ll have to leave certain enemies alive and navigate around them instead, but that’s been the case in every previous game as well; if you don’t have (or don’t wish to use) the necessary weapon, you need to rely on agility instead.

The chargeable Buster doesn’t change that. Like the versatile weapons of Mega Man 2, you are invited to experiment with it, to vary your playstyle with it, to decide situationally whether or not it makes the game easier or more fun to play, without it ever becoming mandatory. You don’t have to master Mega Man 2‘s alternate methods of using the weapons any more than you have to master the chargeable Buster. They’re wrinkles rather than barricades.

The chargeable Buster is this game’s evolutionary equivalent to the slide in Mega Man 3, and for my money it’s exactly as organic. They each allow the effects of a single button to be manipulated beyond their original, singular uses.

In Mega Man 3, the slide made a kind of intuitive sense from a control perspective. The player already understands that pressing A will spring Mega Man vertically skyward for some set distance. Pressing down and A together, then, produces a result that isn’t much of a leap for players to understand: it takes the same spring and moves Mega Man horizontally forward, as there’s solid ground beneath his feet and it’s impossible to jump “down” through it. In other words, the jump’s momentum is deflected 90 degrees. Mega Man’s lying posture reinforces the “down” action visually, and helps players to remember what triggered it.

That’s not to say that it makes immediate sense. No gamer at the time would have learned that A jumped and immediately intuited that down and A would slide, but after the player performs the action once, there’s enough logical connective tissue that they won’t forget. That’s key in a Mega Man game, where small mistakes add up fast and can result in immensely difficult or unwinnable situations. The player needs to learn to slide and remember in a split second exactly how to do it.

And they do. They associate the A button with a sudden rush of movement already, whether they realize it or not. Adding a quick press of down on the D-pad makes a rational sense based on what they already know about how the game plays. (Just in case it needs stating, the reason they couldn’t map the slide to left or right on the D-pad is that Mega Man still needs to be able to move horizontally in the air.)

The charge is a similarly effortless and natural tweak. The player is already used to pressing B to fire. That’s easy. The logical leap to holding B to fire a stronger shot isn’t much to ask of any given player, especially since children — the primary audience for video games at the time — had a habit of holding buttons down, rather than being dexterous enough to tap quickly or modulate their pressure. It’s why you remember jumping a hell of a lot of times into Bubble Man’s spikes as a kid, but probably haven’t done it much as an adult.

A child presses B and, for no reason except that his thumb is already there, holds it. Mega Man begins to flash and a strange sound is produced. Even if this only happens for a moment, the child notices. Now he presses and holds B, this time on purpose. And for a longer period, to see what happens. As such, Mega Man 4 exploits a natural and unavoidable curiosity to teach every child playing it a brand new rule without saying a word. It’s very well done, and a nuanced and impressive iteration on an established formula. Arguably the last worthwhile one the series would ever see.

I imagine I’ll get some quiet disagreement over this, but I also think this game’s approach to utilities was an improvement. Yes, yes, okay, the weapons are hot garbage, but, please, allow me to wallow in my love for a bit before I get to that.

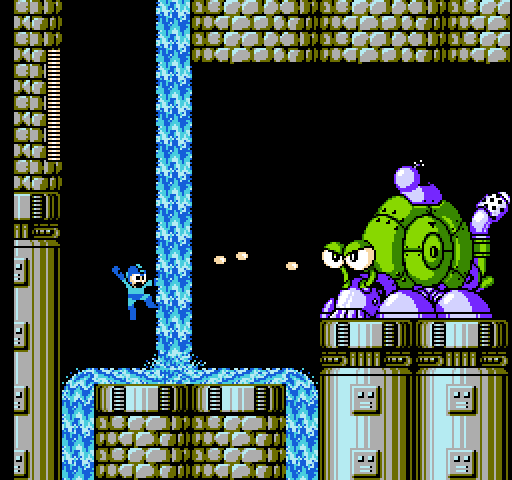

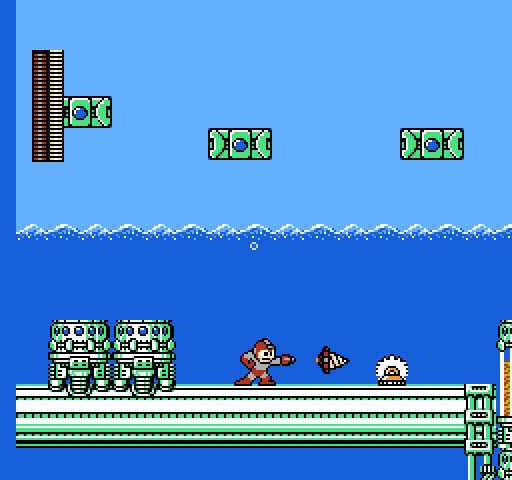

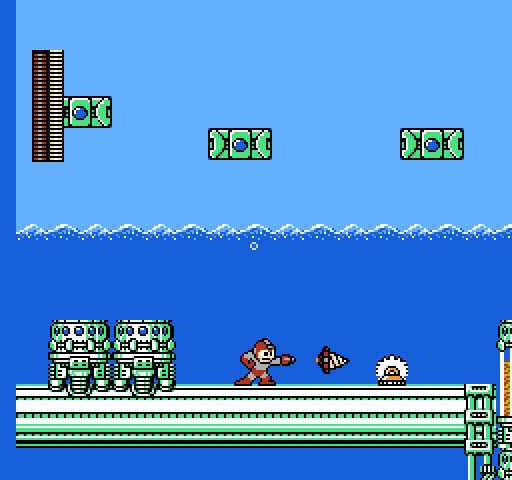

As in Mega Man 3, you collect adaptors for Rush after two boss stages, enhancing his usefulness. In fact, Rush’s forms here are identical to the ones from the previous game — Coil, Jet, and Marine — without any attempt made to introduce a new one. They do fix the Rush Jet so that it behaves more like a steerable Item-2 and less like…well…the broken, untested mess it was in Mega Man 3, but otherwise it’s the same batch of abilities, with Rush Marine being as useless as ever.

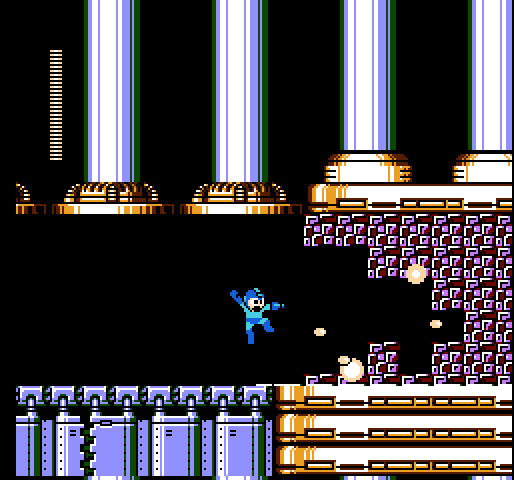

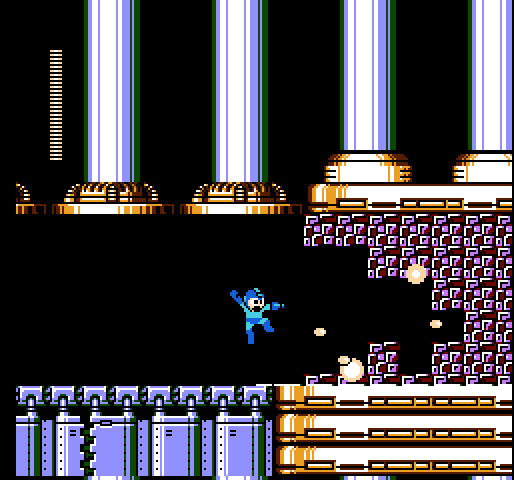

But that’s not all you get. In addition to the Rush adaptors, which you collect automatically by progressing through the game, two true utilities are hidden in the main levels. And I love everything about them.

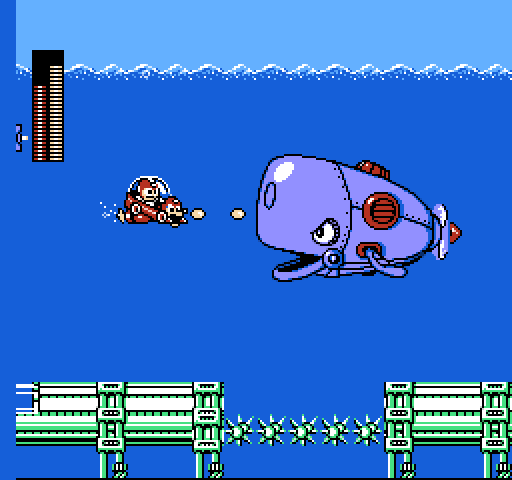

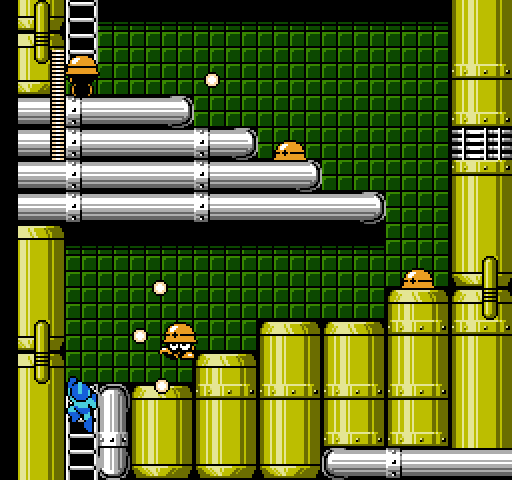

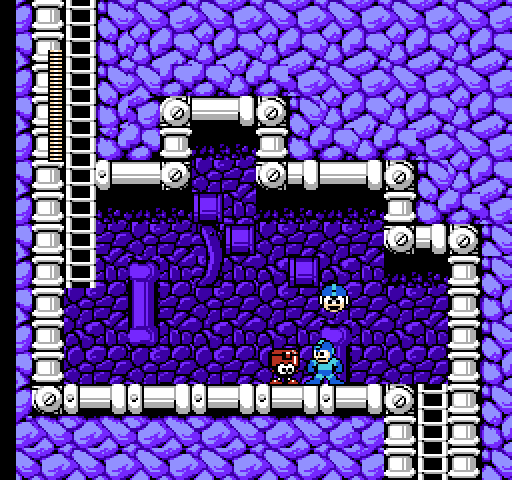

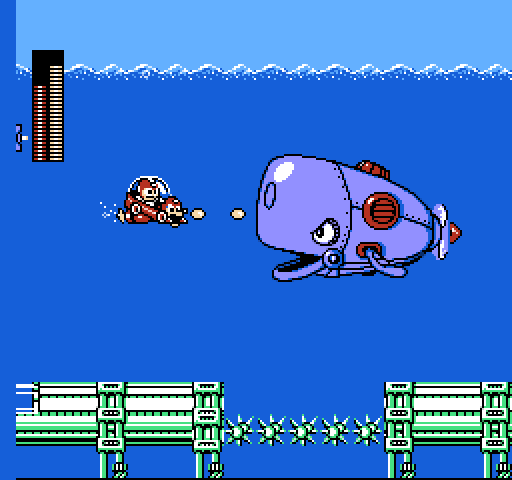

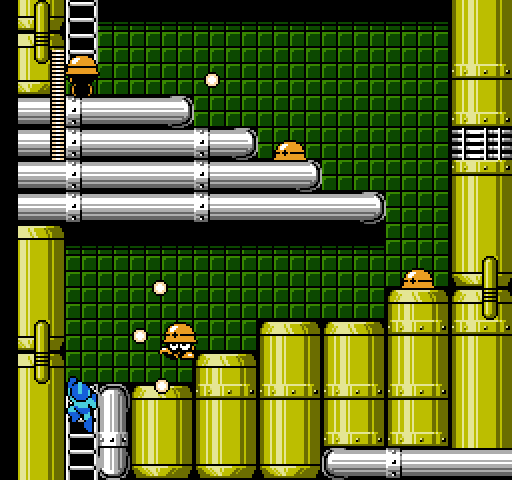

The first thing I love is the simple fact that they’re hidden in the main levels. Not that they’re all that difficult to find; Pharaoh Man’s stage requires you to investigate a curiously open area to the right of a drop, and Dive Man’s stage requires you to…ahem…dive in the only place you can actually do it. Neither are they difficult to reach once you know where they are. But the mere fact that these stages offer alternate, less-obvious routes with genuine rewards for your trouble is an impressive way to vary the traditional Mega Man gameplay. Of course, one could overdo alternate paths, so that instead of adding an unexpected wrinkle to a traditional formula you end up with a tangled mess that works against what players like about the series, but Mega Man 4 does it well. A few alternate screens here, an optional room there, and that’s about it.

Hiding utilities means that you may actually make it to the final stages of the game without a full inventory screen…a first for the series, and the vacancies on that screen are pretty tantalizing if you do finish the game without filling them. What did you miss? There’s only one way to find out.

This also allows players to have different experiences in that final stretch of levels, which isn’t normally a strict possibility. Main Mega Man stages can be completed in any order (with a few exceptions), which means that two players are likely to take entirely different paths through the game…until they get to the final stages, which are sequential. Here, the deviations will be smaller, and will mainly come down to which special weapons and utilities are used when.

But the thing is that both of those players would have all of the special weapons and utilities at their disposal by this point. Their loadouts will be identical, and it’s just up to them to decide what to use or ignore.

Mega Man 4 upends that. Player A gets to the final stages with both utilities, Player B gets there with just the Balloon Adaptor, Player C gets there with just the Wire Adaptor, and Player D gets there with neither.* Four distinct ways of navigating the stages unfold from there, with further variations depending on playstyle. That’s an exciting first.

Then there’s the utilities themselves, which I think are the best in the series.

No, really.

The Balloon Adaptor is, to be fair, pretty dull. It’s essentially Item-1 from Mega Man 2, but it feels more…real. More lifelike. And, sure, that’s down to its recognizable appearance, which looks like a cloth bag inflated with helium, but it’s also in the way it drops down slightly when Mega Man steps on, reacting believably to his weight before continuing to rise. A small touch like that goes a long way toward making the game feel like it takes place in a real universe. This small injection of personality makes the Balloon Adaptor more fun to use than Item-1, similar to the way shaping utilities like a dog made them more fun to use in Mega Man 3.

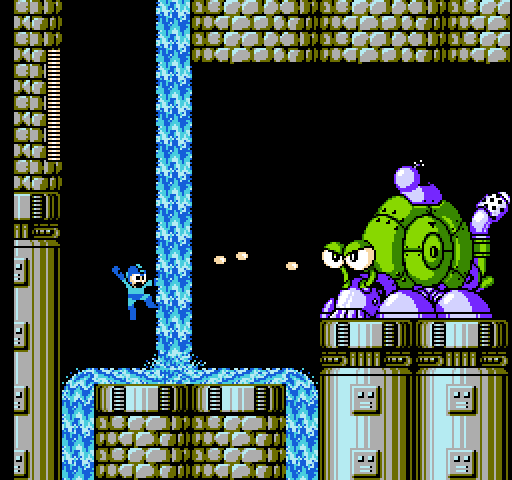

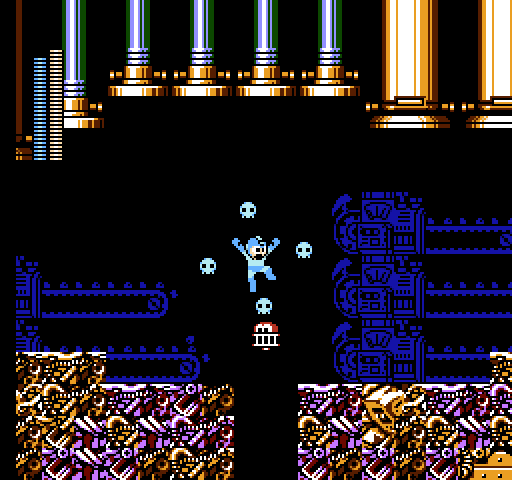

But, really, it’s the Wire Adaptor that stands out. I love the Wire Adaptor, and it’s one of the most fun things to play with in any Mega Man game.

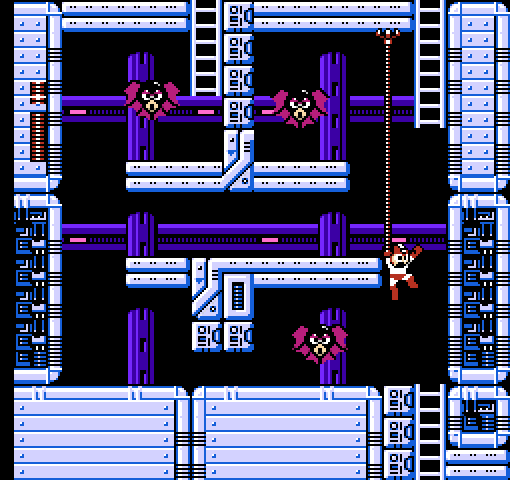

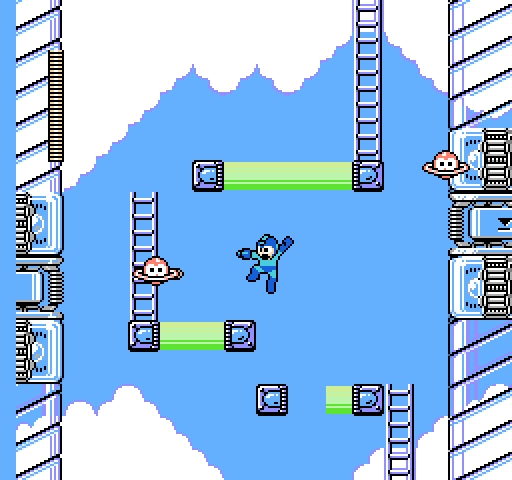

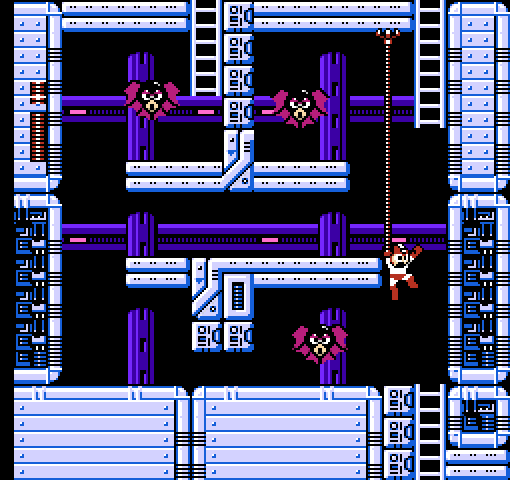

Taking possible inspiration from Bionic Commando, another Capcom franchise, the Wire Adaptor lets Mega Man fire a sturdy cable directly upward. If it collides with an enemy, it will damage or kill it. If it collides with the ceiling or the bottom of a platform, the claw will grip tightly and the cord will retract, bringing Mega Man with it. Alright, so it’s not much like Bionic Commando. But it’s almost as much fun to play with.

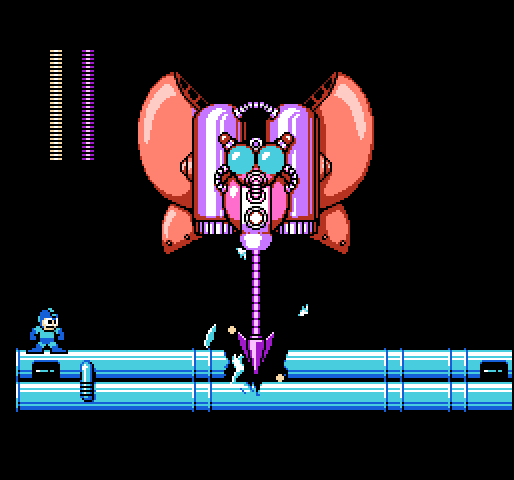

I don’t know why later games didn’t attempt to resurrect the Wire Adaptor. Unlike platforms that rise slowly or jet quickly forward, the Wire Adaptor does more than let you get to new places; it lets you think differently about how to play the game. Since it functions as a weapon (albeit a slow and awkward one) you could actually, conceivably, use it to take out any number of pesky enemies that swarm you from above. I’ve even seen somebody use it to defeat Dr. Cossack late in the game, which was both funny and a tribute to the item’s unexpected versatility.

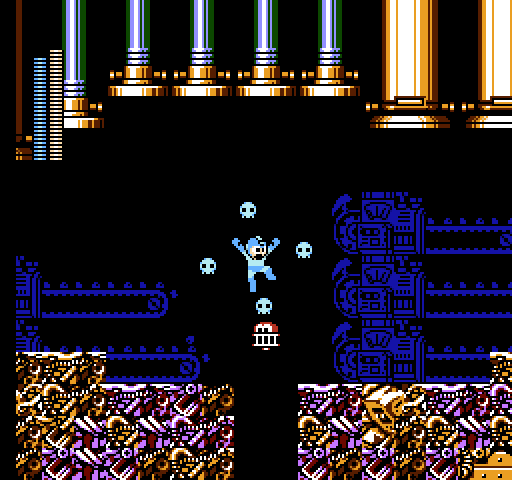

Mega Man is not the most nimble video game hero. He moves at a decent pace, but you couldn’t call it quick, exactly. He can’t duck. He can only fire straight forward with his default weapon, despite the fact that, logically, he should be able to fire in any direction he likes. His jump height isn’t that impressive, and he goes gliding helplessly backward whenever he takes damage.

In short, he’s kind of a klutz. And I think that’s what makes the Wire Adaptor such a thrilling surprise. Now Mega Man moves. He soars upward like a superhero, calling to mind Batman, Spider-Man, and Inspector Gadget all at once. He looks like he’s come so far from the first game. He looks like he’s gotten cooler and…well…better.

Once you have it, it’s difficult to not want to use it. Sure, you could reach that out-of-place E-tank in a few ways, but, man, the Rush Coil is so last year. And everybody starts with it! There’s no fun in that. With the Wire Adaptor you can reach it in style.

But, okay, I’ve babbled about the utilities enough and can’t in good conscience delay talking about the game’s problems much longer. I think Mega Man 4 is great, but I’m not blindly in love with it.

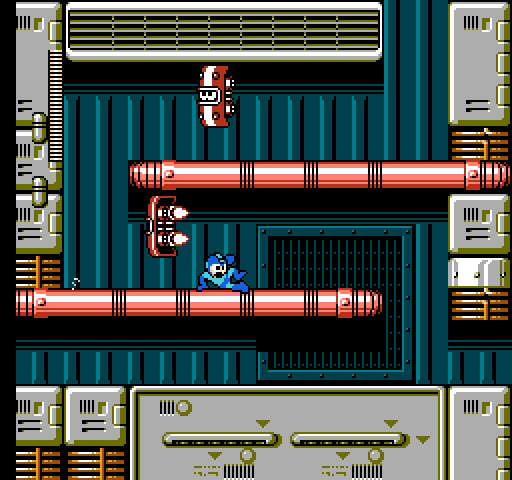

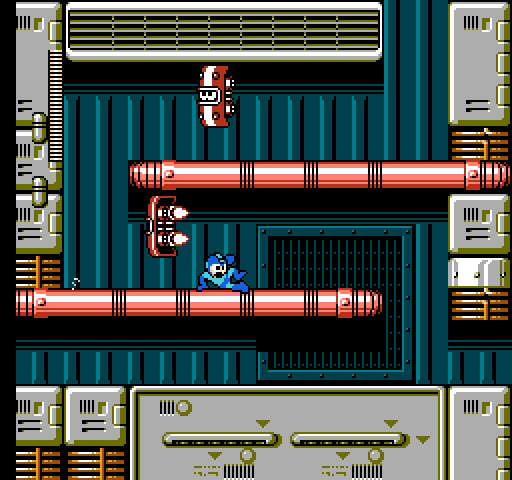

The problems, sadly, start with the main attractions themselves: the Robot Masters.

On the whole, I’d argue that the Robot Masters are still quite interesting, but there’s no avoiding the fact that this is where fan interest began to flag.

Even as a kid I thought the very concept of Toad Man was hilarious. (“We saved the world how many times? Now we have to fight a frog?”) Also, for reasons lost to me now, I absolutely hated the concept of Pharaoh Man. I’m pretty sure I knew what a pharaoh was, and there’s nothing about the level or the boss himself that should have turned me off, but I remember feeling like he was the first truly disappointing Robot Master. Maybe I just didn’t like that he was named after a job as opposed to a weapon or some other more evocative thing.

I know Dust Man gets a lot of flak, but, frankly, he never bothered me too much. He’s an industrial vacuum cleaner with googly eyes. Maybe not the most inspired thing in the world, but a better design, in my opinion, than a guy in a thrift-store skeleton costume and someone with a lightbulb on his head.

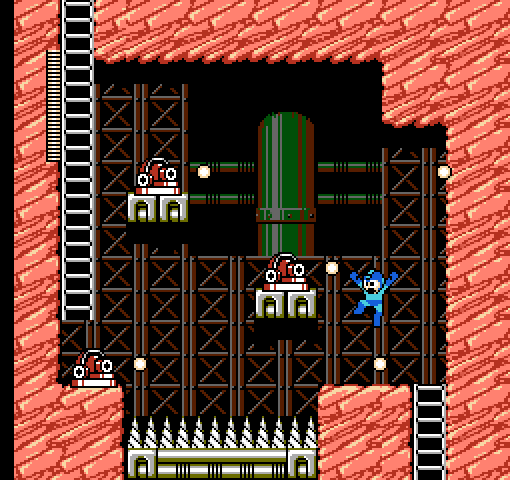

The least inspired design is probably Drill Man, as he’s just…a drill. With drill arms. He kind of sucks, and dueling him is nothing great, either, unless you for some reason enjoy battles in which your opponent spends huge portions of the fight inaccessible. It combines all the fun of waiting with the thrill of doing nothing.

In fact, the Robot Master duels here are pretty tame. The toughest fight undoubtedly comes from Pharaoh Man, who is quick, powerful, and tricky. Of course, he’s absolutely crippled by the Flash Stopper, which freezes him in place long enough to kill him effortlessly. (Quick Man was similarly helpless to the Time Stopper, but it wasn’t enough to kill him unless you played on the easier difficulty setting.) That’s not exactly a complaint, though; it’s up to you whether or not you’d like to essentially skip the fight, and attempting to take him down with the Buster reveals a pretty satisfying battle.

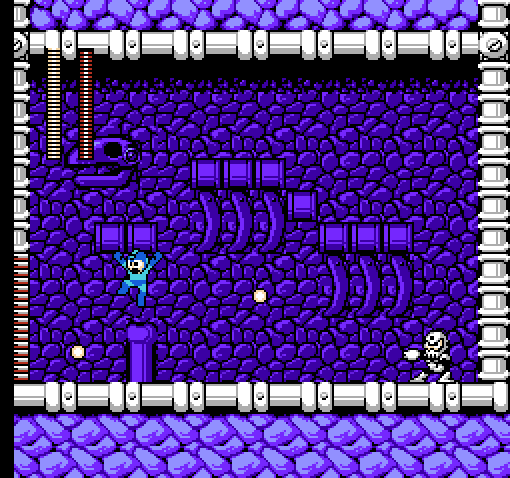

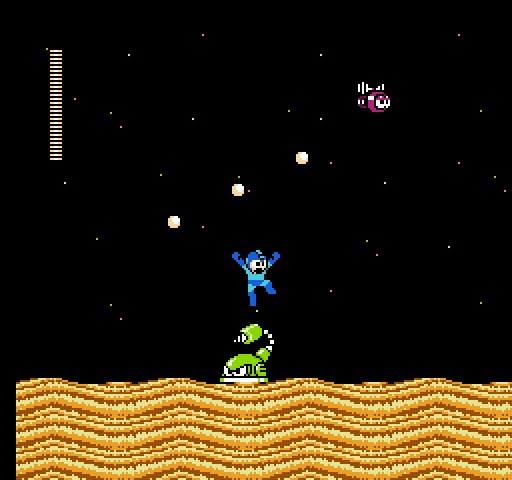

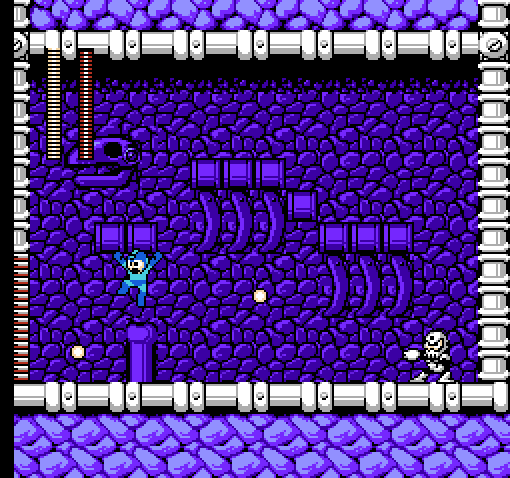

Otherwise, though? There’s really not much on offer. Bright Man is difficult, but mainly annoying, freezing you helplessly in place and colliding with you or gunning you down mindlessly. Dive Man, Skull Man, and Dust Man all follow very simple patterns and don’t seem to have had much effort invested in their programming.

Then there’s Toad Man, who is programmed so legendarily awfully that he’s embarrassing to even fight.

Here’s the thing: yes, it’s possible to lock other Robot Masters into cycles that don’t allow them to attack. Elec Man, Heat Man, and Nitro Man all come immediately to mind, as do nearly all of the Robot Masters from Mega Man 7 if you use their weaknesses. I’m probably forgetting even more.

But in those cases, you need to figure out how to lock them into those cycles, whether those cycles were intended or not. Essentially, you need to crack a code. You need to figure out what the Robot Master does on his own, as well as how he reacts to your movements and to your attacks…and then also figure out a repeatable set of actions on your part that keep him locked into a cycle he can’t break.

It’s not easy, and in most cases it’s not even possible. When it is, it’s thrilling, because you’ve outwitted an artificial intelligence. It’s not Mega Man vs. XXXX Man; it’s mind vs. machine. It’s an organic brain vs. a mechanical one. It’s an important and thematically resonant conflict, so that when you do figure out how to do it, you didn’t just win a battle; you overcame something you were not meant to overcome.

Beat Elec Man? Fine. Beat Elec Man without even letting him move? Now you have something to be proud of.

Then there’s Toad Man. It’s possible to lock Toad Man into a pattern during which he cannot attack. But there’s a problem: you do this by default.

See, doing it to other Robot Masters requires you to behave in unexpected ways, and to have thorough knowledge ahead of time of how your enemy operates. When you pull it off, it comes from hours of practice and possibly even research. It comes from substantial periods of observation. It comes from work, from failure, from repetition to the point that you can close your eyes and picture exactly how a hypothetical fight will go based entirely on what you’ve already learned.

With Toad Man, you just shoot him.

That’s it.

The default thing you do to everything you find in the game.

You press B. That’s how you break Toad Man.

It’s…strange. Every time you shoot him, Toad Man hops harmlessly over you and lands on the other side. So you turn, shoot him again, and he jumps back over.

If you leave him alone, sure, he hits you with the screen-clearing Rain Flush, which is impossible to avoid once it’s been activated. But shoot him — as you undoubtedly will, without any training or practice or foreknowledge — and he slips right into a pattern he cannot escape. The only way to lose to him is to not attack him, something that literally no player would even try. It’s a terribly careless bit of programming in a game that otherwise is decently polished, and it does drag the experience down a bit.

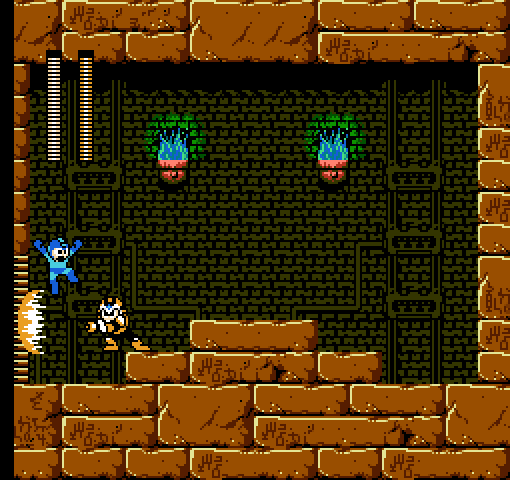

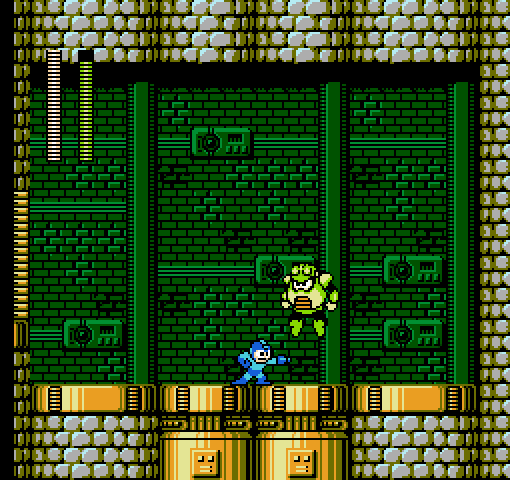

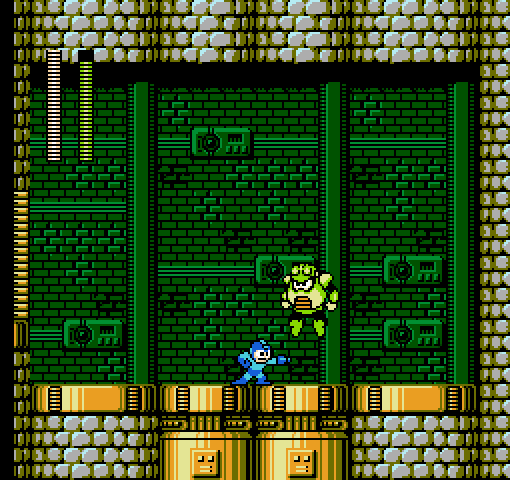

But then there’s Ring Man…my personal favorite Robot Master. Not just in Mega Man 4, but overall.

I love this guy, mainly because he feels like a perfectly tailored, brilliantly responsive fight. There’s also the theme of circularity he has going for him which resonates with me on personal level but…I won’t bore you.

My friend who loved Mega Man 4 is actually the one who explained to me how to defeat him with the Buster…which is not difficult to learn but, at first, is very difficult to execute. When you know how to handle him, when you can recognize his pattern, when you’ve practiced the fight enough to see it with your eyes closed, Ring Man’s duel is the most natural and rewarding in the game. It’s actually fun, requiring a good deal of clever footwork and an ability to keep calm in a room with a fast opponent and a faster projectile.

Ring Man is easily this game’s standout battle, and his weapon — the Ring Boomerang — is the standout in that category as well. The Pharaoh Shot is probably the runner up (it’s chargeable, aimable, and you can use it to cause collision damage!), but, like the Wire Adapter, there’s just something so stylish about the Ring Boomerang that makes it fun to use. It’s big. It’s shiny. It returns. It makes an incredible shhhing sound. It’s all glimmer without gold, I know that, but video games can live and die on glimmer. It feels more impressive than the other weapons, which instantly means that it is.

That about does it for the interesting weapons, though. The Skull Barrier is the most worthless of all shield weapons, the most worthless of all weapon types. The Dive Missile has the same problem all homing weapons in Mega Man have: it doesn’t home in on anything reliably, making it less likely to hit its target than your default projectile. (And that…is…irony.)

Then there’s the Drill Bomb, which illustrates my point about the organic implementation of the chargeable Buster by doing everything wrong. The Drill Bomb is one of only three weapons in the game that can be used in any way more complicated than pressing B. In this case, you can press B once to fire it, and then a second time to detonate it.

…but there’s no indication at any point that this can happen, and I’m sure most players have no idea of this functionality. Which is a shame, because one of the final bosses is weak against the detonation.

The chargeable Buster works because it taps into something people will do unconsciously anyway: hold a button down. With a visual and aural signal, players are clued into the fact that they should hold the button down, at least to see what happens.

The Drill Bomb, though, doesn’t teach players how to use it. They try it, it flies forward like almost any other projectile, and that’s that. There’s no reason to press B a second time, at least not while the projectile is still on screen or before it collides with an enemy. Of course, the easy rejoinder to that is that players would likely try to fire multiple projectiles at once to defeat enemies more quickly…which is true, except that this mainly applies to the default Buster with its unlimited ammunition. The moment you implement strict weapon capacity, as the special weapons do, you discourage players from firing mindlessly.

Many players harp on certain Mega Man games (often beginning with this one) for having unimpressive weapons. As much as I’d love to dismiss this critique, I can’t. It’s valid. And it’s a real problem.

It’s the weapons that should keep these games interesting. They’re how the games both mark and reward progression. And they are what make all of the games feel distinct; they’re the new set of toys you get to play with each time, and they’re perfectly (and evenly) paced in their distribution. By the time you get bored of playing with one toy, you get another. You can’t ask for a more perfect drip-feed than that.

Not all weapons have to be great, of course, but they do need to feel distinct enough to merit playing with them. When they don’t, there’s no incentive to experiment with the new toys, and fatigue sets in more quickly. Players choose monotony over the game’s concept of variety. That’s not their fault, and we know where that leads.

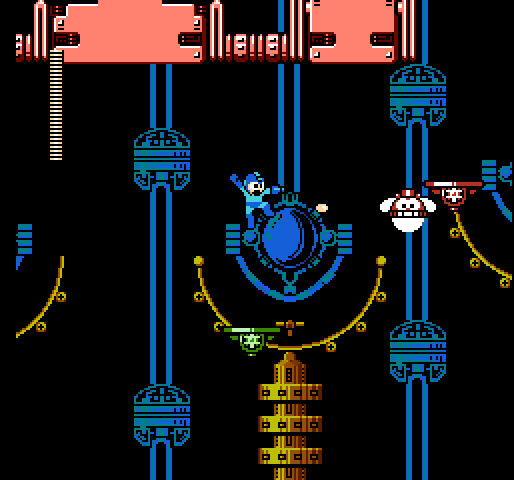

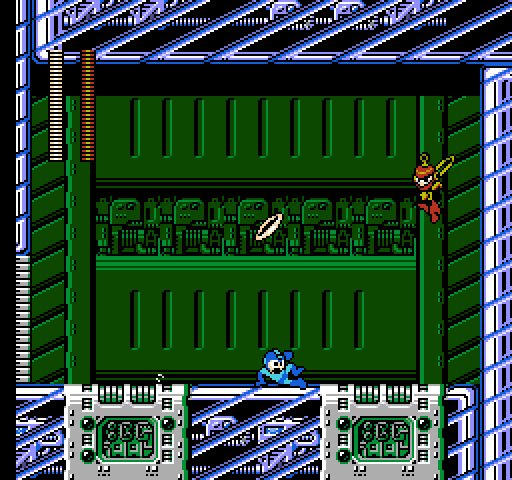

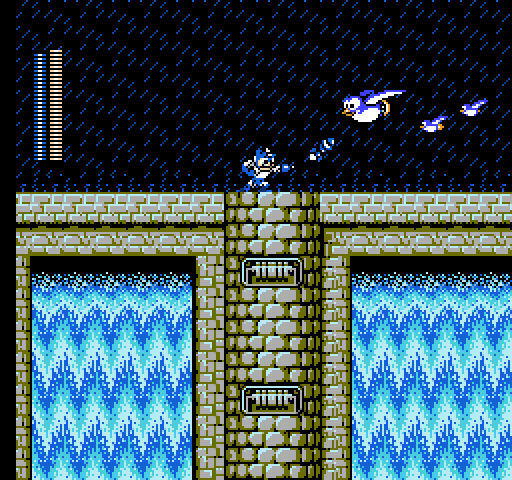

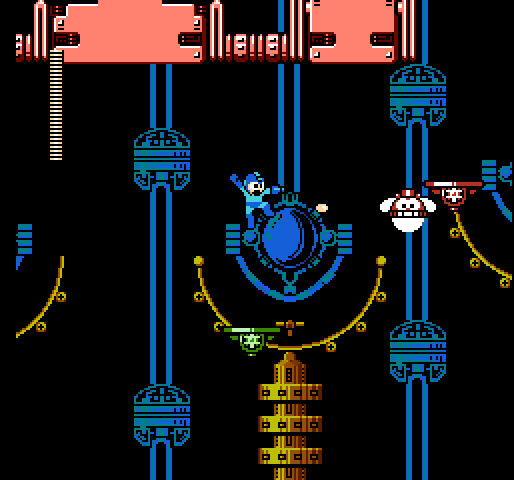

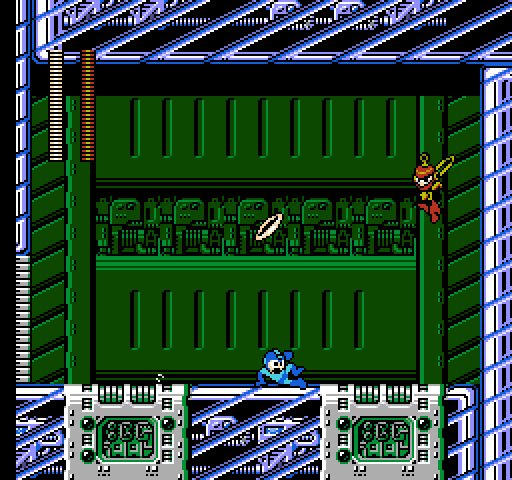

It’s worth revisiting Mega Man 4, though, and it deserves critical reappraisal. No, the weapons won’t scratch anyone’s list of favorites and the Robot Master duels are largely lame, but the chargeable Buster is a thrilling evolution to the formula, and this is arguably the best game to feature it. The music in a few cases is just as good as anything that came before. The addition of another set of fortress stages before Wily Castle is a smoother, more impressive, more fun evolution of the frustrating, flawed Doc Robot stages of Mega Man 3.

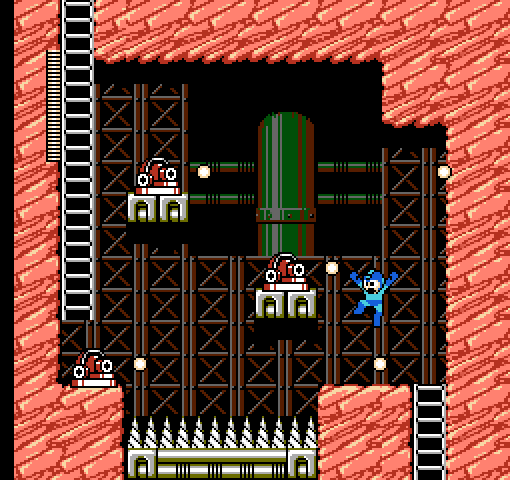

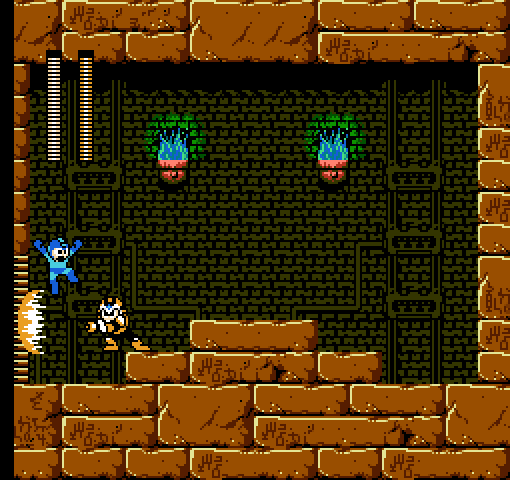

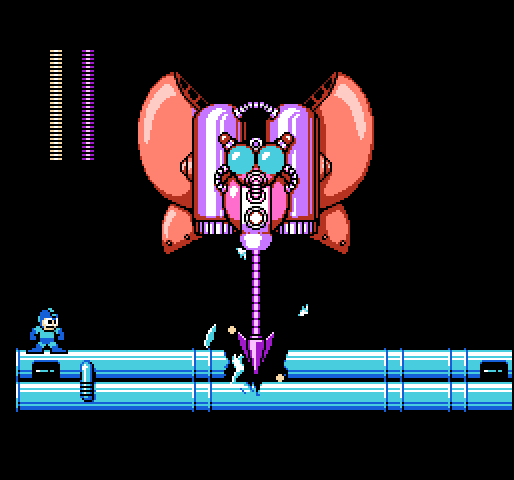

In fact, the fortress stages (both sets) are some of the best in the series. They’re actually fun to play, as opposed to being overcrowded, unfair, punishing gauntlets. The highlight is either Dr. Cossack’s great autoscrolling level with counterintuitive platforms that rise rather than fall, or a Wily stage populated entirely by various versions of the hardhat enemy. Even the final boss is a giant one! …which, yes, is something we saw multiple times in Mega Man 3 but it’s still cool here so leave me alone.

What’s more, Dr. Cossack is an interesting villain, mainly because he’s not one. Sure, the game’s big fakeout (spoiler: IT IS ALWAYS DR. WILY) is predictable, but Dr. Cossack represents a fascinating middleground between the relentless evil of Dr. Wily and the tepid goodness of Dr. Light.

Dr. Cossack is a fundamentally good man driven to do fundamentally bad things for the sake of protecting his daughter. This makes Cossack the most human character we’ve met yet.

The previous two doctors behaved just like their robots: programmed to be good or programmed to be bad. And while the series doesn’t exactly need rich characters with complex motivations to keep players interested, I actually really love that they bother exploring some kind of human emotion with Cossack here. I especially like that he’s so grateful to Mega Man for saving Kalinka that he builds Beat, a helpful robot bird, in the next game as his way of saying thanks. Cossack disappeared from the series after Mega Man 4, but through Beat — through his works — he lives on.

Mega Man 4 isn’t a perfect game. It’s not even close. But it feels so much more polished than its immediate predecessor, even if it doesn’t quite reach the highs of some other games in the series.

Maybe the most important thing to me is just how warm the game feels. How welcoming. How even the final stages don’t seem to want to punish you, or even test you unduly. It just wants you to have fun. Maybe it can’t give you the best time you’ve ever had, and maybe you won’t even remember it a few years down the line. But it wants you to enjoy the time you spend together.

I think that’s reflected in the game’s new supporting robot character: Eddie. He’s just a little red canister with big, friendly eyes that pops in now and then to give you a helpful item. Unlike Rush or Proto Man, he doesn’t have a definitive purpose. He’s just there. He just likes you. Whoever you are…he likes you, and is going to help you push through.

He doesn’t need to be thanked, and he doesn’t overstay his welcome. He just wants to make sure you’re comfortable.

The first time I saw Eddie, I tried to attack him. He didn’t look much different from the enemies I was fighting.

The bullets passed right through him, of course. He waddled up to my feet and tossed me an extra life. For free. I didn’t have to do anything to earn it, and he didn’t even seem to care that I tried to kill him.

Thinking on it now, I expect that most people tried to kill Eddie the first time they saw him. I wonder if the game shouldn’t have let them do it.

Not because I dislike him, or for any kind of dark or cynical reason. I just wonder if Capcom shouldn’t have let your shots connect. Eddie would beam out, of course, but then you’d progress without his helpful item. And each time you saw him, you’d fire again, and he’d keep beaming out. You’d always think you were clever, scaring off an enemy before he ever got the chance to attack.

I wonder if that wouldn’t have been a perfect little echo of the game’s larger theme of the blurred line between friend and foe.

Eventually you’d have the Cossack twist spelled out for you. But you could go the entire rest of your life without learning the truth about poor Eddie.

All because you’ve been programmed to fight.

Best Robot Master: Ring Man

Best Stage: Skull Man

Best Weapon: Ring Boomerang

Best Theme: Dive Man

Overall Ranking: 2 > 4 > 3 > 1

(All screenshots courtesy of the excellent Mega Man Network.)

—–

* Compare this to Mega Man, the only previous game that would have allowed deviation: Player A makes it to the final stages with the Magnet Beam, Player B does not. But there’s no deviation beyond that, because Player B won’t be able to progress, and will need to return with an identical loadout to that of Player A.