I’m not entirely sure what I hoped to see when I dug into Christian horror films, but holy Hell did Remake deliver on all of it and so much more.

Following the bland idiocy of The Lock In and the problematic competence of The Familiar, Remake‘s over-the-top gore, gloriously terrible acting, and consistently muddled moralizing is absolutely perfect. It immediately launched itself onto my list of favorite bad movies, and I don’t see anything knocking it off soon. In fact, at some point, I’ll likely do a trilogy of the bad movies I love most.

This year, though, I thought doing a trio of didactic films would provide a lot of opportunity to speak about religion in general, Christianity in general, spirituality in general, and even basic human decency in general. In short, I thought it would be a great way to open the floor to discussions that wouldn’t normally happen here.

But I was hoping, deep at heart, that I’d get at least one film that wasn’t just disappointing or bad…but was memorably, infectiously, beautifully terrible. And I’ve gotten that with Remake.

In a very welcome bit of happenstance, I ended up with three films this year that represent different kinds of horror. The Lock In was found footage, The Familiar was demon possession, and Remake is a slasher film. What’s more, the sequence in which I watched them formed a kind of natural progression. We started with sinning children, moved up to sinning adults, and now follow parents, whose child is damned by sins those parents committed in the past.

Remake is about the abduction of Megan Slayton, a teenager of the spry age of thirty-six. She gets nabbed by notorious snuff pornographer Twitch, and it’s up to her parents to get her back.

This year we find an unexpected theme running through all three movies: the evils of pornography. In fact, if you showed these movies to somebody who had never heard of Christianity and asked him to guess the central tenets of the religion, I don’t think he’d mention God. I don’t think he’d mention Jesus. I definitely don’t think he’d mention performing good deeds and caring for his fellow man. He may or may not mention the Bible. He certainly wouldn’t mention reading it, aside from consulting it briefly for relevant plot points.

He’d mention monsters and pornography. “Don’t summon demons” and “don’t jerk off” would be the Two Commandments. Not necessarily in that order.

Megan is kidnapped because Twitch worked with her step-mother Rita on a snuff film called Ladyfinger in the past, and he intends to remake it properly this time. (Y’know. Because Rita didn’t die.) He kidnaps Megan as leverage; either Rita comes back to star in the fatal remake, or he’ll kill her daughter on camera instead. Don’t ask why he didn’t just kidnap Rita directly. In fact, don’t ask anything.

Rita has no choice but to come clean to her husband of 15 years, Pastor Carl. She’s been living under a false identity as a way of escaping her past. In addition to saving Megan’s life, therefore, both she and Pastor Carl have to come to terms with Rita’s history, and learn to accept it.

Typing it out like that, it’s…really not a bad setup. It could do with some tweaking, and it’s not the sort of thing I’d write of my own accord, but for a scary movie, it’s solid enough. A killer doesn’t finish the job with one victim, so he tracks her down many years later and threatens to kill that victim’s daughter unless she gives herself up.

That can end a few different ways, and it can play out in thousands. There’s a wealth of storytelling opportunity there, and I’ll give Remake credit for going places I absolutely did not expect it to go. Of course, that’s born of ineptitude rather than creativity, but I’ll take what I can get.

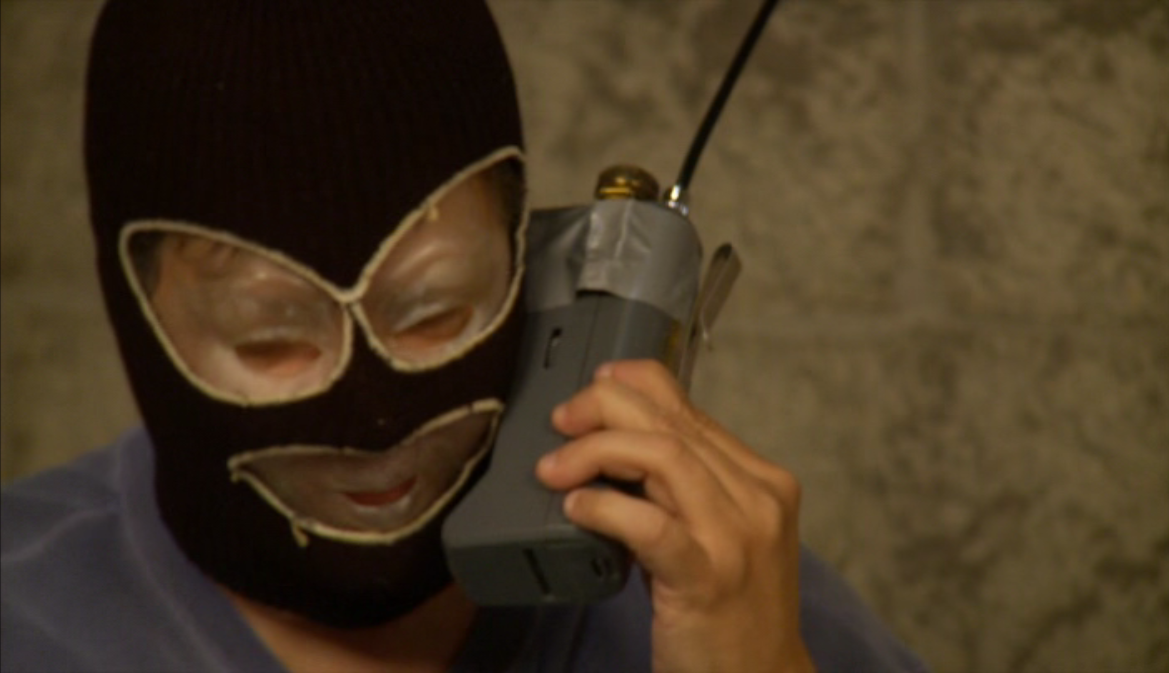

Twitch is introduced to us as a mysterious figure. He wears a mask over another mask, for crying out loud.

He’s most certainly a bad guy. There’s no way to read him otherwise, which becomes surprisingly problematic by the end of the film, and shines light on one major way in which viewing horror through a spiritual lens makes complex that which should be simple. But…we’ll get to that.

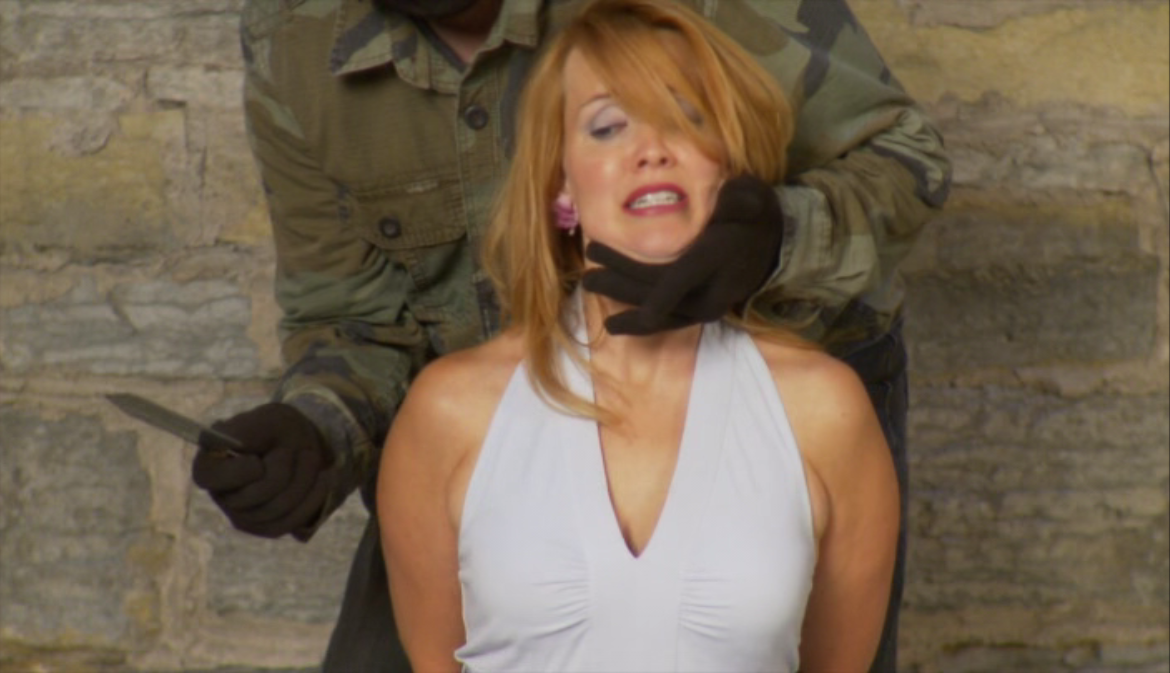

As the film progresses we learn more about what Twitch is doing and why. He is contracted by wealthy clients to produce custom snuff videos. Not all of them feature pornographic content, but when we’re dealing with murdered women, that’s a relatively small potato.

A client requests a woman of a certain description. Twitch hunts down a match, kidnaps her, and keeps her chained up in a basement. He then films himself killing her, and dumps the body somewhere, selling the video back to the client.

What a good Christian film!

I know, I know, I criticized both previous films this month to varying extents for taking place in hyper-Christian, unrecognizable versions of the world. You know, ones in which brushing up against some pornography unleashes actual demons, kids who talk like Ned Flanders are irredeemable sinners, and a cute girl who doesn’t like guns is a living portal to Hell.

So kudos to Remake for being…you know. Actually horrific. I had difficulty relating to the kind of revulsion I was meant to feel toward certain characters in the other films, but Twitch is truly a despicable human being — and therefore a more effective villain — than anything we’ve seen yet.

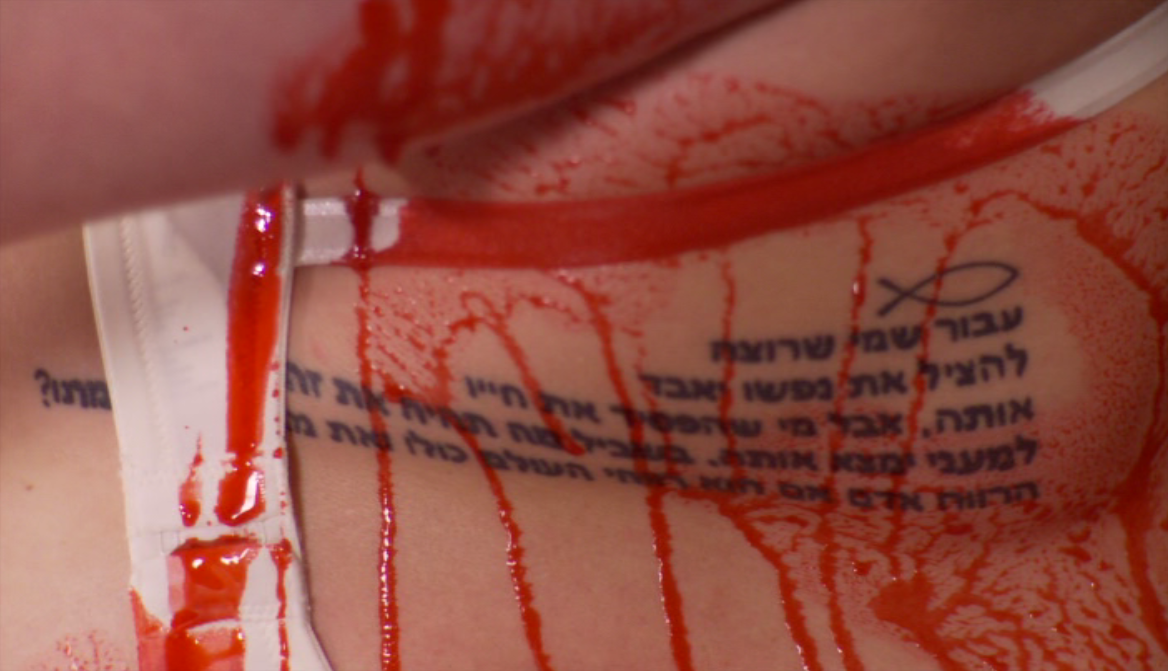

It’s just…jarring, I guess, to see a vocally Christian film chock full of half naked woman writhing around, bleeding, screaming, crying, being carved apart by a deranged pornographer. I think I would have been surprised if the film even suggested those things, so the fact that nearly all of it happens on camera — and happens so frequently — was legitimately shocking.

Of course, it wasn’t actually that bothersome to watch, because it was so clearly fake.

The blood is as thin as tap water. You can see the joins where the fake wounds are affixed to the actors’ flesh. The murders themselves are almost uniformly nonsensical, as three(!) of them hinge upon a small knife suspended from the ceiling by a string. Twitch cuts the string and the knife falls down, striking the victim and instantly killing her. This is impossible, and doesn’t even work by the film’s internal logic.

Twitch hacks away (and removes body parts from!) various women who lie there crying for help, dying slowly and painfully. But when a single, unimpressive blade — think the knife you always deliberately overlook when you need to cut a bagel — falls a few inches, with no force stronger than gravity behind it, and lands nowhere near a major or vital organ, the victim immediately dies.

I kept expecting Remake to explain that that particular blade had been poisoned or something. I even would have settled for it being cursed.

But, no, we learn nothing, and I shouldn’t have expected to from a movie that shows us Twitch disposing of his first victim like this:

Yep, they’ll never find her!

Weirdly, though, it works. It would be one thing if stranding this corpse on a riverbank is what leads to his capture, but it doesn’t. In fact, the police just wander around scratching their heads, wondering how they’ll ever catch a criminal who’s so damned smart.

Remake, as you can probably tell, is dopey enough that it gets away with itself. A smarter film would have to account for far more of this inconsistency. By being dumb, though, Remake earns a pass, and I’m glad it does, because it’s genuinely fun. It’s the kind of film that does something inconceivably stupid and has you howling with laughter…then, as soon as you get a hold of yourself, it does something even stupider.

It’s absolutely perfect, even (especially) at its most misguided. It’s the Christian horror trainwreck I was praying for.

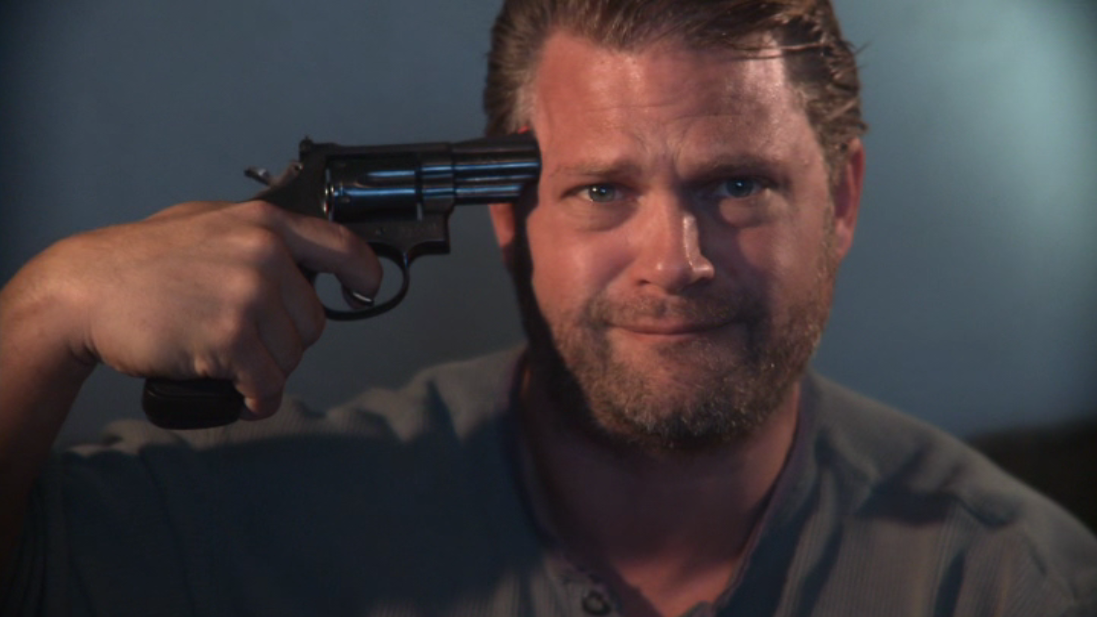

Twitch’s identity is concealed for reasons I can’t fathom. Sure, I know he’d want to wear a mask (or two…) while murdering innocent people on camera, but why keep his identity a secret from viewers? For a while I assumed it was because we’d find out he was one of the characters we’d already met…but, ultimately, no. It’s just some guy who looks like Bill Ponderosa from It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia.

To be fair, we had met him before, but only briefly, at the very start of the film. He was sitting around with his family, and then he left the room. That was it. We didn’t have a sense of who he was, so learning that he’s Twitch doesn’t cause us to re-evaluate our earlier assumptions. Remake treats the reveal as though this is The Usual Suspects or Heavy Rain, not realizing that learning the identity of the killer won’t retroactively inform the way we view everything else. It’s really strange.

In fact, the whole movie is really strange. It’s bizarrely edited, with the soundtrack regularly coming to a hard stop rather than fading out, and quick cuts to irrelevant background imagery — such as this liquor holder — to incompetently mask transitions between takes.

It’s also bizarrely written, with tonally incompatible moments of high drama paired with what seem to be comic interludes, such as when good Pastor Carl insults his wife’s appearance while they’re waiting for instructions on how to get their daughter back. Or a long, meaningless exchange between Pastor Carl and a hooker in which she pridefully explains how she gets easy money from a “retard.”

And a major plot point hinges on the fact that Twitch bugged the Slaytons’ land line, preventing them from calling the cops…but they also have cellphones, so why don’t they just call the cops on those? Why not set the film twenty years in the past if you want the land line to matter?

But, most of all, it’s bizarrely acted. This is both the film’s biggest liability, and the main reason to keep watching it.

The characters speak in a thick, inappropriately comical Midwestern drawl, pudgy action zero Pastor Carl the drawliest among them. It lends the entire film an amateurish air that makes it feel like a production of the Lower Milwaukee Afternoon Players.

There’s also a profound, unnerving detachment between the emotion certain scenes demand and the total lack of it in the actors. I’d blame the director for this, but Pastor Carl is played by the director — Doug Phillips — so we can direct the blame wherever we like.

In total fairness, Kelly Barry-Miller often does good work as Rita. She’s convincingly busted up by Megan’s kidnapping, and if she feels out of place (which she most certainly does) it’s because nothing else in the film rises to meet her. She’s investing effort in the role, which is admirable even if it’s not always successful. I think it’s safe to say that she comes out of Remake with the smallest amount of blame.

The most blame unquestionably goes to Phillips, who is uniformly awful. I genuinely think he could benefit from taking acting lessons from Tommy Wiseau. At least Wiseau knew that he should emote, while Phillips treats scenes in which he’s brewing coffee with the same emotional gravity of scenes in which he’s fretting over the safety of his daughter: none.

The lack of emotional response from Pastor Carl is genuinely strange. Megan is his daughter, after all; she’s only Rita’s step-daughter.

And yet I believe Rita is truly worried about her, and how this will all pan out. Pastor Carl, in contrast, seems to have read the script and knows that his severed head will end up wrapped in a towel on the coffee table, and so resigns himself well in advance of doing anything at all to save her.

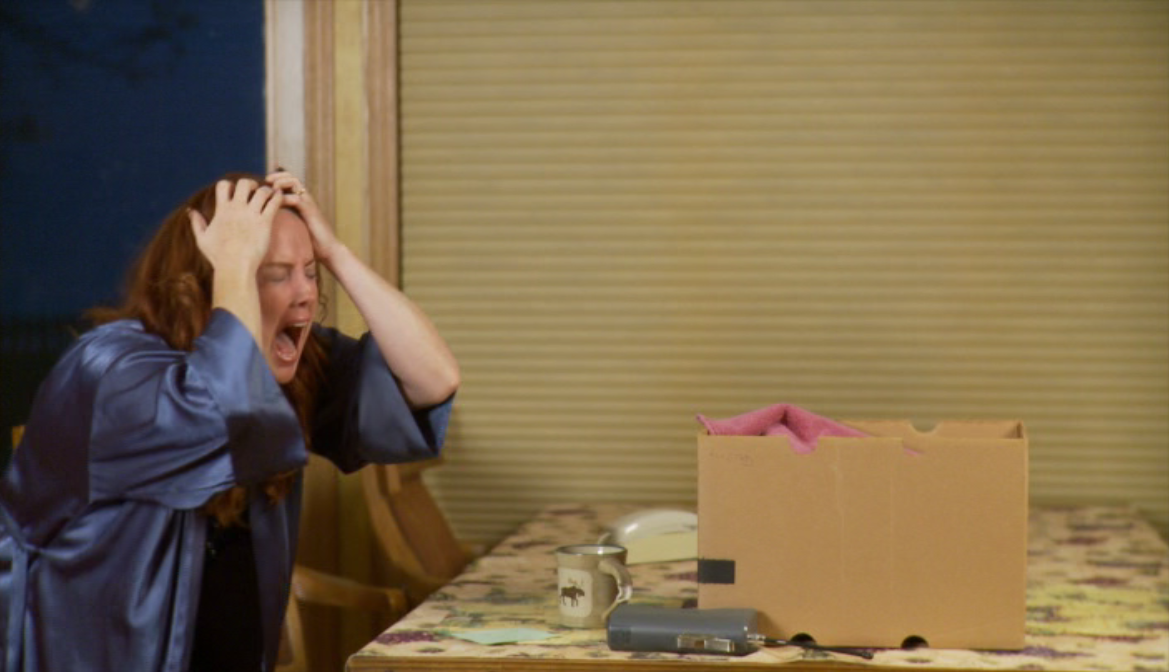

It’s really strange. Very early in the film, Twitch delivers a package to the Slaytons. Pastor Carl — who has to be oddly prompted by his wife before he thinks to open it — finds a few things inside, most notably Megan’s severed finger.

Rita howls believably. What a horrific thing to see! How barbaric! What a frightening indication of how much very real danger their daughter is in!

…but Pastor Carl doesn’t react at all. He just slowly unwraps his own daughter’s finger from a mound of bloody gauze with no more emotional response than he’d have shelling a peanut. He even goes over to the sink to rinse it off.

Think about that!

Think about opening a package to find your wife’s, husband’s, child’s, or friend’s severed finger. You’d drop it. You’d weep. You’d doubt your eyes. You’d call the police. You’d vomit. You’d react.

Pastor Carl does none of that. Indeed, he does nothing at all except confirm that it’s hers. (He recognizes the ring…after rinsing it.) His reaction is so strange that I expected him to reveal that it was a fake finger, meant to freak them out. After all, Rita is across the table, so maybe it looked more realistic to her from a distance. Since Pastor Carl was holding it, he must have been able to see “Archie McPhee” stamped on the side of it.

But no. It’s real. It’s Megan’s. His daughter has been confirmed mangled. And, of course, if this is what Twitch does to her first, as a warning shot, whatever happens next is bound to be far worse.

Oh well. Guess I’ll just sit dog-faced in the kitchen some more.

It’s inhuman. It’s strange. And the fact that he’s the writer and the director makes it even stranger. It’s his movie! Doesn’t he realize how this should be impacting his character? What is the disconnect here?

The disconnect, I guess, is between Remake and everything we know about human behavior.

Bolting a troubled marriage plot onto a child rescue plot isn’t necessarily a bad idea. Those are compatible topics, and once we introduce one kind of family tragedy it’s fair that it would expose another. And that’s exactly what happens here; Megan being kidnapped is one thing, but it forces Rita to explain a decade and a half of dishonesty that threatens her relationship with Pastor Carl.

Good. Both of those things should be explored. But Pastor Carl is one of the major links between the two stories, and he’s just a fucking boob.

He starts out well enough. He’s a believable — if in no way charismatic — preacher. The film opens with his long sermon about forgiveness…about how forgiveness is meaningless if you don’t believe you’re forgiven. And that’s fine.

It’s far longer than it needs to be, though, and we keep cutting to weird static shots of just about every person in the parish, though we’ll never see most of them again. I wonder if Phillips had to promise everyone in this real-world church a closeup in his movie in exchange for them letting him film there.

Almost immediately after that, though, he gets weird. First there’s the fact that he’s at least 75 years older than his wife. Then later in the bedroom he gets upset that Rita won’t let him touch a nasty scar on her stomach. She says it’s because it’s the result of a traumatic attack at the hands of a junkie.

Fair enough, I’d think, but he gets pissy about it and chews her out for living in the past. He leaps almost immediately to, “I might as well just sleep on the couch, then!” Which is certainly a respectful way to respond to the woman you love when she politely asks you not to jam your thumb around inside a wound that hurts both physically and emotionally.

He’s actually pretty awful to Rita overall. Once Megan is kidnapped it would be fair to assume that the stress of having a missing daughter is getting to him. But we see from the start that he’s a dick well before that, and I suspect that’s because Phillips at no point considers modulating his performance. Pastor Carl is always a snarky, venomous asshole, which might be why he has nowhere to move when it’s time for him to show a more extreme (or even different) emotion.

Megan’s kidnapper sends one of those bulky radiophones so her parents can communicate with him. He offers to exchange Megan for Rita, and this is where Rita has to come clean about her past.

She confesses to her husband that she used to star in pornographic films. And was hooked on drugs. And was also a prostitute. And starred in a fake snuff movie. And lied about her parents being dead. And is currently living a fake identity to get away from her past. And follows pornography newsgroups on the internet, which allows her to keep abreast of the ins and outs of hardcore porn production, presumably because that’s a hobby of hers in the same way that memorizing baseball scores might be to someone else.

Pastor Carl is understandably shocked.

He’s less understandably a fucking asshole to her. She’s opening up to him. She’s clearly fragile. She needs her husband right now. And all he can do is carp at her and judge her for her past.

I’m not saying this is good writing. In fact, I assure you it’s not. I offer as evidence the following, which is an excerpt from Rita’s explanation of her past / some stuff Phillips pasted into the script from Wikipedia:

RITA: Softcore is where you’re naked, but the sex is fake. Usually fake. Lots of legit films have a scene or two. That’s how men get addicted. And some women, too.

PASTOR CARL: Women getting addicted? But women aren’t visually stimulated.

RITA: That’s not quite true! Women are stimulated emotionally. So if a scene is between the stars and the guy has been nice to the girl all through the film, if the scene looks tender, like they really care about each other, then yeah. Women can get hooked on that. It’s like a red-cover romance novel, but done visually. Once people get used to getting off, they start watching late-night cable flicks that are mostly softcore scenes with a paper-thin story line.

PASTOR CARL: Why do directors stick that crap into legitimate films in the first place?

RITA: It’s banked. With some genres, you can’t get distribution in certain countries unless you have a sex scene or a nude shot.

So, to Pastor Carl’s credit, there’s nothing natural, realistic, or believable about that exchange, and there certainly isn’t anything insightful. So maybe his constant sniping at her, cutting her off, and making jokes and jabs at her expense is just slightly less monstrous than I initially thought. The conversation isn’t one that actual humans would have, so why should he respond with any humanity?

Regardless, he comes off as rude, condescending, and in no way supportive. Which, to some extent, is fine. He has every right to hear about his wife’s past — one which she deliberately lied about and hid from him — and decide that this isn’t what he signed up for.

But, frankly, there’s a much more pressing issue than arguing with your wife and repeating back and forth the Webster definition of bukake: your daughter has been kidnapped. Her finger is sitting, I guess, in the soap dish. She’s already been disfigured, and every minute that passes brings her closer to further violation and death.

Pastor Carl thinks the most important thing at this point is to be a fuckwit to his wife. His wife who is actually crying. His wife who is actually terrified. His wife who is actually grieving over what’s happening to Megan.

And it’s not her real daughter. Why on Earth isn’t Pastor Carl distraught on the floor? Why is he more intent on playing Who’s on My Wife First?

Pastor Carl is just a grumpy lump of crap who shoots down his wife’s ideas — and feelings, and needs — one after the other without providing any of his own. When Rita brings up the sermon he gave on forgiveness, he says it applies to her as well, though he wishes it didn’t.

He’s a loathsome, insufferable jerk. Remake does see him as flawed, but not to the degree he actually is. And when he’s eventually redeemed, he doesn’t seem like any less of a dickweed. The only admirable thing about him is that, at some point, he finally decides to get off the couch and do something.

Yes, our favorite complaining, geriatric dumbass eventually does take action. I guess he had no real reason to be motivated; Twitch said on the radiophone — again, this is a world with cellphones — that they could have some time to decide whether or not Rita would take Megan’s place in the snuff film, but he wouldn’t give them too much time to decide…

Then he sets a deadline a week out.

A week is a really long time in a case like this, Twitch. You may have bugged their phone, but that doesn’t stop them from waltzing into the police station and telling the cops everything they know. That’s plenty of time for professionals to track you down. And the Slaytons could easily record your voice…they’d have all the evidence they need to get law enforcement mobilized immediately.

And yet the police never caught this guy, because he’s way too smart.

Action Grandpa figures, hey, what the hell, it’s been a few days, let’s try to get my kid back. He sets out without telling Rita, and for an even more glorious stretch, Remake becomes sort of like a version of Taken starring the guy you most recently sat near at a KFC.

Pastor Carl’s equivalent of Liam Neeson’s particular set of skills is an overwhelming tendency toward bitchiness. He couldn’t possibly seem more put out. He’s like an old man at a deli who keeps getting angrier because each time he asks for potato salad he gets macaroni salad. It’s hilarious.

His ultimate goal is to track down Twitch, but he can’t do that because a) he doesn’t know how to do that, and b) he wasted all of the time Twitch gave them not even attempting to do that.

He works his way through a variety of characters as he follows the trail. First he talks to a taxi driver because, in his words, “I figured a hackie hears everything.” Our 108-year-old hero, ladies and gentlemen.

The hackie tells him to talk to a prostitute he knows, because she has some kind of sophisticated number-blocking feature on her phone, which is totally not just some standard function all cellphone users have access to and holy crap this movie really should be set twenty years in the past.

The prostitute sends him to the woman who taught her how to use her iPhone, I guess, and that woman installs a compass on the radiophone, so he can track down Twitch.

An actual, physical compass.

How in God’s name does a compass lead Pastor Carl to the bad guy? Yes, the film tosses out some “signal tracking” palaver, but a compass is magnetic; a phone couldn’t control where it points unless it were physically moving a magnet around inside, and that’s if you could even get the phone to relay the information it receives about the signal to a fucking compass in the first place.

And, again, this is a world with cellphones. Use the GPS, fuckers! Yes, I know that’s now how GPS works, but that’s ALSO NOT HOW A PHYSICAL COMPASS GLUED TO A RADIOPHONE WORKS.

The entire time Pastor Carl spends tracking his daughter down, he grumbles, gripes, complains about how people are dressed, gets huffy with them for having sex lives, and expends more energy making helpful strangers feel bad about themselves than he does pursuing Megan.

At one point a woman gets blown up by some lens flare. As always, don’t ask.

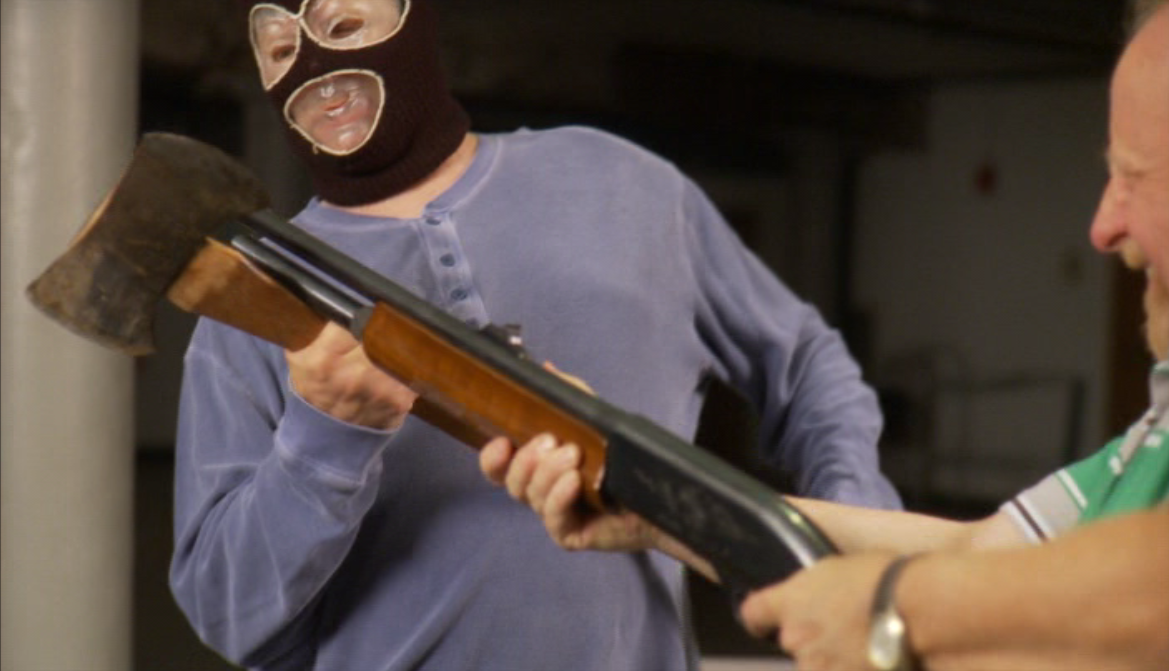

Finally, Pastor Carl makes it to Twitch. He has a shotgun and he’s not afraid to use it, except, I guess, that he is, because he doesn’t use it. Twitch — instead of outright murdering Pastor Carl, Megan, or both — challenges him to a fight with bladed weapons only. Pastor Carl refuses to drop his shotgun, offering to use that as a fighting stick instead.

He’s sure taking his time to hash out rules about this duel rather than shoot the head off the guy who kidnapped his little girl. You should be overcome with rage, here, Pastor Carl!

Twitch, idiotically, allows this. He doesn’t even tell Pastor Carl to take the ammunition out. He essentially just says, “Okay, but you promise not to shoot me, right?” Pastor Carl promises, clearly not telling the truth, except, I guess, that he is, because he doesn’t shoot the guy who kidnapped Megan.

Remake seems intent on establishing a polar opposite of Chekhov’s famous dramatic principle: “Pastor Carl’s Gun” states that a gun introduced in the first act must be held harmlessly during a slapfight in the third.

The confrontation between Twitch and Pastor Carl is less a clash of the titans than a clash of the tits. They are literally fighting over Megan’s future; the winner will decide what she does next, and what is done with her. This is life or death. This is her fate. And we get the least dynamic, most underwhelming fight scene in horror movie history.

These two just smack weapons together for a while, slowly, getting easily winded and trying hard not to hurt each other, because this movie can’t afford insurance. The most action we see is the jiggling of their beer bellies. An axe-wielding pornographer brawling with a shotgun-toting preacher has absolutely no right to be anywhere near this dull.

Anyway, Pastor Carl loses and we at least get the biggest laugh in the movie out of it: Twitch wraps his severed head in a towel and mails it to Rita.

At this point in the film it may seem that Pastor Carl accomplished nothing and died in vain, but that wouldn’t be fair to say. What he actually achieved in death was the scarring of his daughter forever with visions of his Earthly form being hacked to pieces by a serial rapist.

There are two things that happen before Pastor Carl goes idiotic into that good night, one of which is great, and the other of which is extremely misjudged.

The movie deftly established sexual troubles between Pastor Carl and Rita by showing us that she didn’t like him plunging parts of himself into a nasty scar. Since then, we see the two of them bicker and fail to achieve intimacy. They both pray, which is a fair thing to do when their daughter is kidnapped. Pastor Carl realizes while praying that he’s not being supportive of his wife, and can’t really ask for God’s help while he’s making other things on Earth worse for himself and others.

This is a good thing.

“I’ve thought it over,” he says, “and here’s the scoop. I’m still not going to forgive you, because there’s nothing to forgive. If I heard how you got out of porn and turned your life around, and it was anybody else, I’d say they were brave and resourceful. Why should it be different because it’s you?”

Pastor Carl was holding her to a different standard than he’d hold anyone else, and I think that’s actually a pretty insightful moment. We’ve all done that.

When a friend or family member or significant other hurts us, it stings far worse than if a distant acquaintance hurt us in the exact same way. When we care about people, we tend to be harsher on them, or at the very least expect more from them. Which can lead to us being unfair and inconsistent in our dealings. We can confuse people with our seemingly outsized reactions to things they didn’t think were a big deal. Pastor Carl recognizing this, and apologizing for it, is a big step. Okay, he doesn’t actually apologize for it, but he’s not calling his wife fat, ugly, or slutty, so for him that qualifies.

That’s the good thing that happens. It requires us to ignore the fact that he’s also treating everyone who’s not his wife like scum, but, still. Good thing.

The misjudged thing that happens follows immediately on from this moment: Pastor Carl and Rita both get horny and have hot sex all night.

You think I’m fucking with you?

I am not fucking with you.

Once again: their daughter has been kidnapped. Days have gone by without any word from her. She may already be dead. At the very least they know she’s chained up in some basement somewhere, and they have no assurance that she’s even being fed or clothed. She is likely sitting in her own filth, being tormented and humiliated by a man Rita knows is making a snuff film. She has already had her finger cut off for fuck’s sake. She’s definitely disfigured, likely raped, possibly dead. And this is the time her parents rediscover their sexuality?

I…

I really can’t even fathom it.

Throughout most of the film I was just surprised they were able to sleep. When I have a big meeting the next day I have trouble getting shuteye. If my daughter were abducted by the villain in a slasher movie I would be up all night, worrying myself to death. Rita and Pastor Chris, on the other hand, evidently see these as perfect conditions to get sexy.

I am completely and utterly gobsmacked. It may be the single most misguided creative choice I’ve ever seen in a film, and I say that with the full knowledge that Remake also features a sequence in which Twitch films a snuff-film homage to Al-Qaeda beheading videos.

You think I’m fucking with you?

I am not fucking with you.

This is also the only one of Twitch’s videos we see for any real length, so I guess it’s the one Phillips was most proud of coming up with.

Anyway, once Rita receives Pastor Carl’s severed head in the mail, she decides she might not be able to rely on him to sort this out. So she calls Twitch on the radiophone and says she’ll do it…she’ll trade her own captivity for her daughter’s freedom. Of course, at this point a week has gone by since he secretly killed Megan, so Twitch scrambles to find a lookalike.

No, for some reason, she’s still alive. I don’t know about anyone else, but I think if I had a plan that involved kidnapping, extortion, and murder, I’d want to move that shit along as quickly as possible.

Rita has a trick up her sleeve, though: Megan’s boyfriend Tony.

Oh, right. I didn’t mention Tony. He calls the Slaytons all throughout the course of the film, worried because he hasn’t heard from Megan. He uses a cellphone, because he remembers what year it is. They keep giving him cagey answers, but I guess at some point, off camera, Rita tells him the truth. It’s a shame we didn’t get to see that scene, because how in the Hell do you explain to your daughter’s boyfriend that she’s been held in captivity by a notorious murderer for a full week and nobody’s even told the cops?

Speaking of which, why does Rita get Tony and not the cops?

Anyway, Rita is forced by Twitch to cut her own finger off before entering the building. Don’t ask why; Rita doesn’t either. She must know the film is wrapping up, because she has a serious disinterest in motive at this point. Want me to cut my finger off? Here ya go; let’s keep this moving, chop chop.

Twitch indeed lets Megan go when Rita shows up, but Megan — being human — attacks him as soon as she’s set free so that both she and her mother can escape.

She’s proud for a moment, but it really is only a moment, because I guess she forgot that he’s a guy who kills people with knives and he kills her with a knife.

Well, she doesn’t die. She just bleeds for a while and Tony rushes in to save the day!

Actually, my mistake. Tony dies.

Alas, poor Tony! You were…kind of in the movie, briefly.

Twitch spends enough time murdering Tony that Rita understands she picked the right guy to use as a meat shield. Then Twitch falls over, or something, and that stupid knife that hangs from a string falls down and stabs him.

The movie’s essentially over, so of course it does anything but end. Twitch gets a dying monologue with more words than most people speak in their entire lives.

It goes on for several minutes. The guy’s ostensibly bleeding out, but he just keeps rattling off instructions to Rita. For long stretches the actor forgets he’s meant to be dying, and fails to convey any degree of pain whatsoever through his voice.

TWITCH: You are a worthy opponent. You beat me fair and square. Now I want to help you. You’re not out of the woods yet. The Ladyfinger producers will kill you if we don’t cover this up. Destroy the evidence. We must make it look like a random abduction, that I was after you and not your daughter, for some reason. In the other room is my computer with all of my files, with no password for the operating system. Bring up the command line. Unmake.exe. Run it. It will erase my files so that not even the cops could recover them. In the cabinet next to my computer is my copy of Ladyfinger. Destroy it. Run with the story, and you will be free.

Fun fact: in the entire history of mankind, nobody’s dying words will ever contain the phrase “no password for the operating system.”

Again, this is an excerpt. It really does feel sometimes as though Phillips is trying to write the least naturalistic, tone-deaf dialogue imaginable. If so, I’d like to congratulate him on a job well done.

But that isn’t nearly the strangest thing about the ending.

No…the strangest thing actually ties into the theme of the film, which is forgiveness.

And forgiveness is great! It’s both a spiritual and secular value. Preach forgiveness, and we can all benefit from the sermon. Fine.

But Remake illustrates it in a really strange way: the film ends with Rita sitting with a dying Twitch…and forgiving him.

For stabbing her and leaving physical and emotional scars she never got over, she forgives him.

For stalking her and tracking her down in her new life, she forgives him.

For forcing his way into her home and kidnapping her step-daughter, she forgives him.

For cutting off Megan’s finger, she forgives him.

For planning to murder Megan unless she sacrificed her own life, she forgives him.

For cutting off her husband’s head and sending it to her in the mail, she forgives him.

For forcing her to cut off her own finger, she forgives him.

For nearly killing Megan, she forgives him.

For actually killing Megan’s boyfriend, she forgives him.

For all of the abductions, rapes, and murders he’s committed, she forgives him.

I was all set to deride this. To mock it. To call it inconceivable and idiotic.

But the more I think about it…the more I admire it.

Forgiveness is an important Christian virtue. Jesus made this clear when he was asked how many times we should forgive someone who sins against us. Seven times? Seventy times? Jesus replies, “Seventy times seven.” Which isn’t a math problem; it’s an assurance that if you’re looking for a specific number…if you’re seeking a boundary beyond which we can finally stop forgiving someone…you’re asking the wrong question.

Forgive. That’s the answer. Stop counting. Stop measuring. Forgive. You’re all humans. Forgive, dammit.

And yet, that’s the (literal) Christian answer. We worldly dopes do set boundaries beyond which we don’t forgive. Steal my wallet, and maybe I’ll forgive you. Steal my car, and I probably won’t. Hurt me, and maybe I’ll forgive you. Hurt somebody important to me, and I probably won’t.

Jesus’s answer, though, makes it clear that we shouldn’t do that.

A secular film can feature a hero who forgives one set of characters while refusing to forgive another. Any action film fits the bill here, and a lot of horror as well. Characters are flawed, but we (and the hero) still want some to live and others to die. There’s a boundary beyond which we don’t offer and don’t wish to see forgiveness.

A Christian film can’t rightfully behave that way. If we’re going to raise the issue of forgiveness, everyone must be forgiven.

Including the snuff pornographer.

And…I see that as a bit much. It’s a difficult pill to swallow. At the very least, Remake has me wondering about that.

Would I forgive the man who kidnapped my daughter and killed my spouse? No. Fuck no. Clearly no.

And yet…should I?

I still want to say no, but there’s a lot of wisdom in that “seventy times seven.” Forgive. Be a man. Move on with your life. Let go of grudges. Granted, a grudge against a snuff pornographer is bound to be a larger one than most…but does a larger grudge make it more worth clinging to?

It’s a valid question, in theory, but in practice…in illustration…it’s really hard for me to agree with Rita’s forgiveness of him here.

Remake already has ways to illustrate forgiveness. Natural ways that we wouldn’t question. Pastor Carl can forgive his wife for misleading him about who she was, and Rita can forgive her husband for being a griping, complaining dicksack. That would fulfill the theme of the film, and if the movie ended with Rita beating Twitch to a bloody pulp I never would have seen an inconsistency. He’s the slasher in a slasher film! Get him.

And I’m tempted to say that this would have made the movie better.

Maybe, though, what I mean is that this would have made the movie less challenging.

Remake isn’t smart. And yet, it may have accidentally done something intelligent. Jesus commands us to forgive. Easy. Whether we live by that commandment or not, we at least understand it. Forgive. Got it. That’s clear.

By pushing this commandment to the genuine extreme — it’s hard to imagine Twitch doing anything worse to Rita and her family than what we already see here — and reinforcing our obligation to forgive him for what he’s done, Remake challenges us.

Could you have found Megan? Maybe. Could you have defeated Twitch? Maybe.

Could you have forgiven him?

Now we’re struggling.

All three of those things, you need to do. I need to do. We need to do. At least, if we want to be the good guy.

Remake is the only film in this year’s trilogy that is brave enough to end without a restoration of the status quo. The events of The Lock In turned out to be a masturbation nightmare or something. (I’ll have to ask the church elders about their findings.) The Familiar ends with Laura saved, Sam redeemed, and Rallo exorcised.

But Remake has consequences. The film ends with Rita meeting with the police.

For her own safety, she needs yet another identity. She needs to be shipped off somewhere, again, to start all over. The life she built for 15 years is gone now, and she needs to start building another one from scratch. Megan is being uprooted, too. Her boyfriend and father are dead, and she’ll be haunted forever with visions of them being murdered by the psychopath who kidnapped her.

Again, Remake isn’t smart. I don’t think any of this is deliberate. But the events of the film, I think, raise the question for the audience anyway. Rita did the good Christian thing by forgiving him.

But should she have?

Her past, present, and future have all been dashed by his hand.

Does that deserve forgiveness? Can we possibly forgive it? And if we can…are we foolish to do so?

Was Remake made not to reinforce what Christians already believe — as the other two films were — but to get them to challenge it and come out stronger for having arrived at the answers themselves?

The best films make us think, but not exclusively so. Sometimes you can find valid questions — and intriguingly withheld answers — in the least likely of places.

Christian horror, which I didn’t even know existed a few months ago, was certainly the least likely place I expected to find anything. And yet here I am, weeks later, still mulling a question I never thought was complicated to begin with.

That’s a pretty neat trick. And one hell of a welcome treat.

Happy Halloween, friends.