Though my Rule of Three theme this year has been films based on novelty songs, I haven’t actually talked about how these films use their own source material.

I don’t mean that I haven’t talked about how they adapted their source material — I won’t fuckin’ shut up about that — but rather how these films use the actual songs upon which they were based.

In Harper Valley PTA, for instance, the Jeannie C. Riley version of the song plays in its entirety during both the opening and closing credits, bookending the movie…which itself contains scenes and characters so true to the song that lyrics are lifted entirely.

It’s the “tell ’em what you’re going to tell ’em; then tell ’em; then tell ’em what you told ’em” approach, and I actually kind of like it. The original song brings us into the world of the movie and then out of it again, with the closing credits giving us a chance to reflect on how the film expanded on the germs of characterization the song gave us.

That’s not all, though; throughout the movie, various instrumental arrangements of “Harper Valley PTA” play as diegetic background music. We hear different versions everywhere from Alice’s beauty parlor to the merry-go-round Stella rides with Willis. It’s a really nice and creative touch that winks at the audience without being unbearably cutesy.

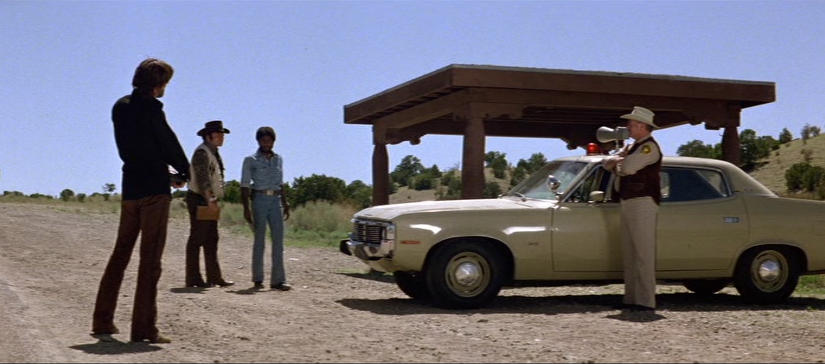

In Convoy, the original song is both a recurring presence and completely absent.

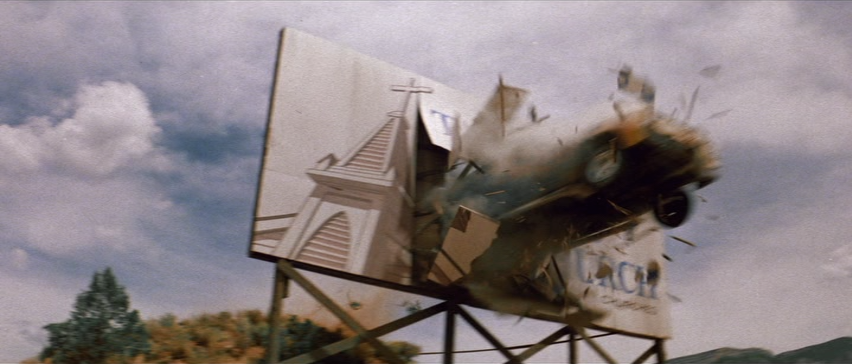

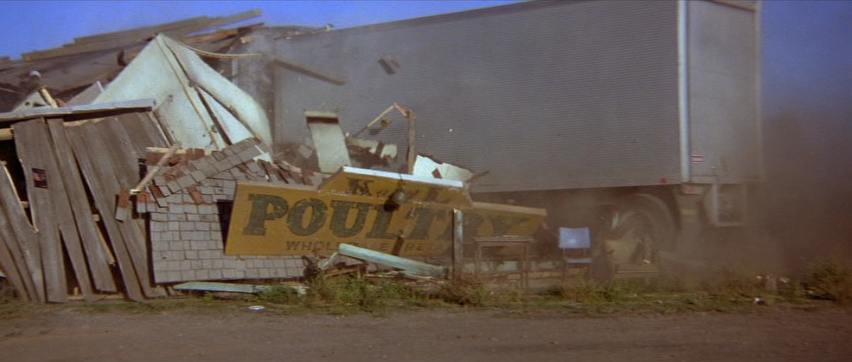

During certain establishing shots and scene transitions, “Convoy” kicks in like an omniscient narrator, only we don’t hear the original lyrics. I’m almost certain it is C.W. McCall who performs the rewritten verses, which lends the rewrite an air of legitimacy, but I can’t be sure. (McCall is obviously credited for the song in the film, but whether or not that extends to the new verses, I don’t know.)

The film-specific verses aren’t great, but until I listened to the song again in comparison I wasn’t sure they were film-specific. They feel very true to the sound, mood, and quality of the original song, and each reader is welcome to take that observation in whatever spirit they please.

We never hear the original “Convoy” at all, and we don’t get any kind of chorus. Perhaps they cut it because the “rockin’ through the night” part would have reminded people that they forgot to include a scene in which any such thing happens. Instead, this version of the song describes which characters are where at any point in time, which seems unnecessary considering the film also uses subtitles to establish that information, but what do I know.

So Harper Valley PTA included the original song and some instrumental variants and Convoy rewrote the lyrics to better fit the action on screen. Two interestingly different approaches.

Now we have Purple People Eater, which treats its original song like suppressed scripture. It is an incantation so powerful that it at first summons and later banishes a horrifying demon.

I somehow doubt that was the movie’s actual intention but, well, here we are, kids.

Purple People Eater was written and directed by Linda Shayne, who I think it’s safe to say wouldn’t recognize narrative if it fell from space and moved into her garage.

Shayne has been in a number of films as an actress, but as a director she might be most famous for the notorious Flyin’ Ryan, perhaps the only magic-shoes movie that has no interest in letting its character use the magic shoes. She’s also done two other films (Little Ghost and The Undercover Kid), so I think it’s likely we’ll get a Linda Shayne retrospective for some future Rule of Three.

Purple People Eater represents Shayne at the absolute peek of her abilities. It’s more coherent, more creative, and more charming than any of her other works. Also, it is not coherent, creative, or charming at all.

Still, though, it’s worth remembering as you experience Purple People Eater that it was somehow all down hill from here.

The movie stars a young Neil Patrick Harris, in the role for which he will certainly be remembered. He plays Billy, a boy we’re constantly told has no friends despite the fact that…you know…we meet some of them. He also brings home lots of animals — which seems like the kind of thing you’d only establish if it were going to come into play at any point, but I’m no Linda Shayne — and has talent in art and music.

Our story begins with Billy’s mother, father, and older sister all leaving immediately and forever, because they have nothing to do with the movie we’re watching. I guess it’s nice that we’re not keeping a bunch of characters around for no reason, but why introduce them in the first place? The film would play out exactly the same if these three characters had been dead for years by the time the story began.

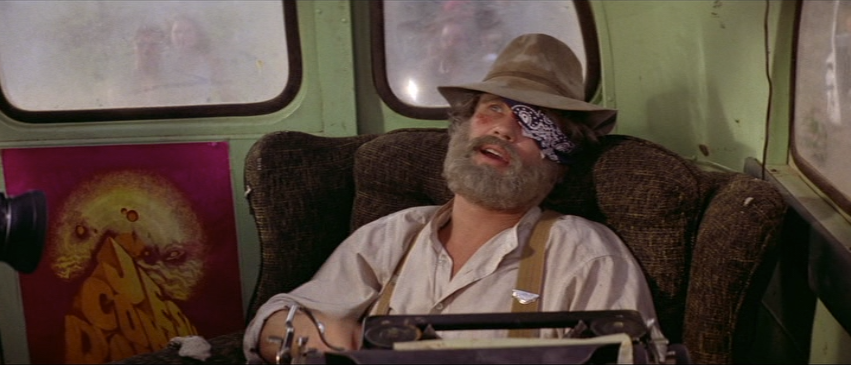

Billy and his little sister Molly are left in the care of Grandpa Ned Beatty, in the role for which he will certainly be remembered. Beatty, in a decision that makes us pity grandpa by proxy, takes the film seriously. It’s probably an overstatement to say he gives the performance his all, but he certainly does try to find and occupy a space in grandpa’s mind that makes any kind of sense. Purple People Eater genuinely did not deserve the effort.

When I refer to a space in the character’s mind that makes any kind of sense, I’m referring to the fact that we’re supposed to simultaneously accept that grandpa believes the undisguised space alien living with him is just some kid from Billy’s school and that grandpa is not intellectually disabled.

And Beatty…actually kind of strikes that balance. Not always, and not especially well, but that’s more the fault of the film than his performance. Beatty manages to be just doddering enough that you buy his confusion and lovable enough that you excuse the (many) moments during which you can’t buy it. He also plays grandpa as a goofy enough figure — I mean this in a good way — that he might not care that the kid is actually an alien; grandpa is having fun and that’s what matters.

The reason grandpa is having fun is that he’s connecting with Billy. We’re explicitly told that grandpa doesn’t live far from Billy’s family — it seems to be a quick couple of minutes by car — so I’m not sure why they never connected before. Neither of them seem reluctant to start a relationship; it’s more like they just waited for a film crew to show up before they bothered.

Overcome by his proximity to youth, grandpa decides to live life to the fullest by…painting his walls.

Billy helps him do this — you might think the movie temporarily forgot Molly exists, but there’s a major scene later centered around the fact that nobody supervises her at any point — and grandpa invites the boy to check out his old records.

Billy becomes the only child in 1988 to rapturously read the names Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, and Chubby Checker off a bunch of records. Seriously, this movie seems like it should take place decades earlier, when a child might actually know these musicians, or have heard their songs anywhere outside of commercials for The Sizzler.

He puts on “Good Golly, Miss Molly” and dances around. Kid fucking loves “Good Golly, Miss Molly.”

You would be forgiven for wondering what any of this has to do with the fucking Purple People Eater. Seriously, we’re about a quarter of the way through this movie about a puppet monster from space before the puppet monster from space shows up.

It finally happens when Billy plays Sheb Wooley’s “Purple People Eater” on the record player. Grandpa probably would have seem him come to Earth, too, if he hadn’t passed out from the unventilated paint fumes hours ago.

Within the universe of this film, Wooley was less some guy who sang a monumentally shitty novelty song and more a divine prophet issuing clear and detailed warnings of things to come.

At least, that’s how Shayne seems to treat the song. It is a holy text from which she shall not deviate. Everything Wooley sang 30 years ago must come to pass this night.

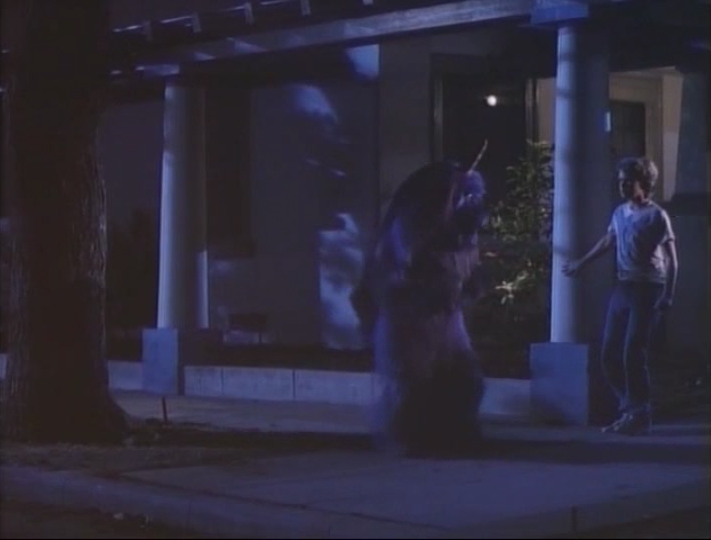

Verily, the Purple People Eater comes out of the sky, as Wooley foretold. He lands in a tree, because that’s what the lyrics say he did. He hops down to the ground and plays “a crazy ditty with a swingin’ tune” through the horn on his head, just as we were promised in the song. He comes to Earth to “get a job in a rock and roll band,” again, as Wooley so immaculately predicted.

And, yeah, Billy does start a band later but you’d think maybe the Purple People Eater would have visited The Rolling Stones or something instead, since they’ve already got their operation up and running, but whatever.

Shayne has every right to adhere to or deviate from the lyrics as she sees fit, but if “Purple People Eater” the song exists within the universe of the film, it has to be a prophecy, right? It can’t just be coincidence. This thing isn’t sort of like what we hear in the song; it’s line for line doing and saying the things the song said he would.

And, of course, there’s the description of the beast. He has one eye and one horn. He has wings to fly. He’s purple. Musical notes float out of his horn when he plays music so you know he isn’t hiding a kazoo in his asshole.

But there’s one detail that’s notably excluded. Have you spotted it? I’ll give you a hint: it takes up two thirds of the film’s own title.

The Purple People Eater — for that’s what this is, what the song is about, what the film is called, and what the creature is constantly referred to as being — doesn’t fuckin’ eat people.

So, okay. It’s a kids’ movie. I don’t expect the Purple People Eater to spend the film picking bits of Neil Patrick Harris from between his teeth. But Purple People Eater never even addresses this.

There are a thousand ways you could resolve this discrepancy and still remain family friendly. You could have the Purple People Eater try to eat a person and get told that that’s not appropriate on Earth. You could have him say that he usually eats people but he’s currently on a diet. You could reveal that the word “people” refers to something different on his planet. Fruit, say.

But you have to explain it. You can’t call a movie The Flying Bus if the bus doesn’t fly. You can’t call a movie Digging a Hole if no actual or metaphorical hole is dug. And you can’t call a movie Purple People Eater if the purple thing isn’t eating people.

The movie even seems to give itself a reason to acknowledge this, one way or the other, as Billy and his grandpa are both covered in purple paint when the thing arrives. And later in the movie the Purple People Eater quotes the “eatin’ purple people and it sure is fine” bit from the song. So whether you think the Purple People Eater is a purple thing that eats people or a thing that eats purple people, you’re going to come away disappointed.

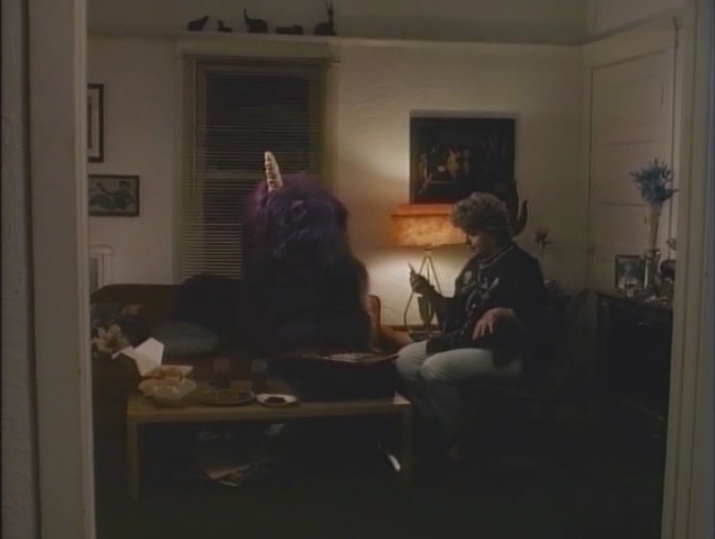

Anyway, the kid has an alien friend now, and grandpa is immediately convinced it’s a child in a costume. Which is fair enough at first.

But then the child moves in with Billy. And never goes home. And never takes the costume off. And plays music without an instrument. And sleeps hanging upside down. And can’t seem to say much aside from “Billeeeeee” and Sheb Wooley lyrics.

Everybody just seems to go along with it. They meet the Purple People Eater — neither he nor Billy come up with a better Earth name for it than “Purple” — assume it’s a kid in a costume, and never question any part of it.

Well, actually, the nosey neighbors the Orfuses do question it, but only so they can be ignored. The rest of the town is perfectly fine assuming this is just some kid whose parents never ask about him or want him back. Also he walks like a full diaper is an integral part of the costume they think he’s wearing, so they should at least offer to change the kid.

Ultimately, though, it doesn’t matter what Shayne has to do to get the Purple People Eater into Billy’s life. What matters is that he’s there and together they can have all kinds of exciting, silly adventures.

Or the alien can play gin rummy with old ladies. Whatever. I give up.

Yes, the plot is that a very old woman named Rita, played by Shelley Winters in the role for which she will certainly be remembered, is going to lose her home to the evil landlord Mr. Noodle.

In fact, Mr. Noodle is so evil and such a landlord that a lot of old people are going to lose their homes. I think you will agree this is a job only Doogie Howser and a store-brand Cookie Monster can handle.

To the relative credit of Purple People Eater, Mr. Noodle is indeed a bad hombre. Harper Valley PTA and Convoy both had villains who lagged far behind the heroes in acts of villainy, but here Mr. Noodle is clearly the dick of the piece, putting profit ahead of the happiness and safety of the elders who rent apartments from him. He even shows up to Rita’s birthday party just to let her know she’s old and poor and will shortly be homeless.

Rita, anxious / scared / depressed, collapses upon hearing the same news she’s heard several times before in this film, and the paramedics show up.

Grandpa asks one of them if she’ll be okay, and the paramedic’s tone is clearly negative. “The most important thing right now is that she want to live,” says the paramedic, which is one hell of an out for him. If a patient dies he can just say, “He didn’t want to live, I guess. I thought maybe he did but now we see he didn’t.”

The unwashed alien crawling with space diseases visits Rita in the hospital with a card that says I LOVE YOU. Rita says she loves him, too.

Purple People Eater is the only space-puppet movie in which the extraterrestrial travels millions of light years to fall in love with Shelley Winters.

For a movie about a boy and his blob, there’s precious little alien content. Billy bonds with his grandfather, which does not require an alien. Billy starts a band with his friends, which does not require an alien. Billy helps some old people die where they are instead of somewhere else, which does not require an alien.

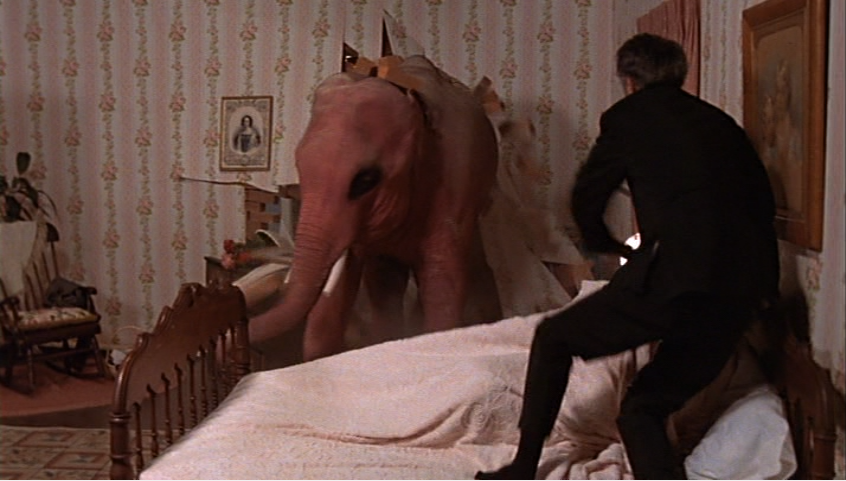

The only real “alien” thing the Purple People Eater does is go fucking berserk in Chuck E. Cheese.

It would be impossible to figure out what’s going on here if the film didn’t outright tell us. It’s just the Purple People Eater making noise while a whole bunch of shit flies around. Thankfully, Shayne has the kids explain that the Purple People Eater ate some chili peppers and now is hiccuping.

So add “leveling a restaurant full of children because he ate something hot” to the list of things he does without anyone doubting that he’s a kid in a costume.

And that’s…pretty much it for alien hijinx. He does use his alien powers to rescue Molly, which is good because everyone else forgot she was in this movie.

Honestly, for reasons that have nothing to do with the Hiccuping Pepper Eater, this ends up being far and away the best scene.

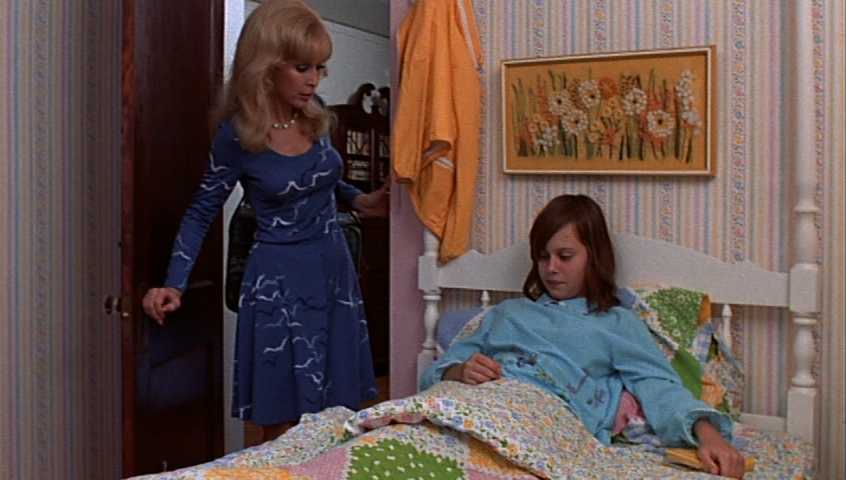

Molly is played by a tiny little Thora Birch, in the role for which she will certainly be remembered. I have a very low tolerance for child actors, not because they’re terrible (though they are uniformly terrible) but because I never think they’re as cute as the directors want me to think they are.

If a kid stumbles over his line reading, I don’t care. He’s a kid. He’s dumb. Move along. But if the camera lingers on him or a scene drags on too long because I’m supposed to be charmed by some little idiot who probably doesn’t even realize he’s in a movie, I get sick of him fast.

A child being a less-than-stellar actor is an understandable real-world limitation in film. But a child meant to charm the hell out of an audience is a director’s conscious decision.

All of which is to say tiny little Thora Birch is genuinely charming and adorable, probably because Shayne just lets her be an actual kid.

The rescue scene is the perfect example. In it, Longfellow the dachshund wanders out onto Billy’s second-floor balcony. Molly calls after him, but he doesn’t come. She crawls into view wearing a dinosaur hat and Jesus Christ if only every child in movies were actually this cute.

I have no idea why she’s wearing it. It’s never explained or even mentioned. And that’s perfect. Was she terrorizing Longfellow? Was she just wearing a dinosaur head because she’s a kid and has nothing better to do? I almost wonder if tiny little Thora Birch just wanted to wear a dinosaur head and Shayne let her.

Don’t let that sound dismissive, because “Shayne just let her” is a massive compliment, as we’ll see.

Everyone gathers around and panics because Molly is about to fall to her death, so the Purple People Eater flies up next to her and…that solves everything somehow. Fuck that.

The good part is that Ned Beatty and Thora Birch have a little exchange afterward. And I’m referring to them by their real names for a reason.

THORA: The dog wanted to go on the balcony.

NED: That’s a bad doggie, Longfellow.

THORA: Longfellow?

NED: Bad doggie.

THORA: I like him.

And holy hell does my cold heart melt.

See, that wasn’t in the script. I don’t say this with any knowledge, but I do say it with complete confidence.

I say it because it’s too real. We hear Thora Birch slur her way through lines like any other child actor elsewhere in the film. Here, she’s just talking to a kindly old man, a kindly old man who happens to be really good with children himself.

Ned Beatty is being a silly grandpa figure to a little girl who, for that moment at least, really does see him as one.

All of that is to Shayne’s genuine credit, and I wish we got more of this here and in her other films. Because kids are cute, but only if they’re given the chance to be actual kids. The moment you give them a script and direction, they’re no longer being themselves. That should be obvious. They’re suddenly acting…something they don’t actually know how to do.

But get Ned Beatty to riff with a child, and let that child be a child, and you get a perfect little adorable moment like that one. Purple People Eater is one of the worst films I’ve watched for this (or any) series, but it also brought me what might be my favorite moment.

It’s also deeply amusing to me that tiny little Thora Birch has such a lovable, perfect moment with Ned Beatty and not with the giant alien puppet designed specifically to appeal to children, but hey, what can you do.

Of course that’s not what the movie’s about so let’s get back to that.

Billy starts a band with all the friends we were told he doesn’t have, including Dustin Diamond, in the role for which he might actually be remembered. They’re immediately great at playing songs thirty years older than they are, and they become locally famous.

At one point in the movie someone hires them to play at his daughter’s wedding, and he ends up loving their act so much he offers them a contract because he’s a record company executive. Quite why he didn’t hire a band he represents and which he would already know would put on a good show rather than take a chance on a bunch of grade-schoolers, I don’t know. Why the contract never comes up again I know even less.

They band is called The Purple People Eaters, and their front man is the Purple People Eater, who they refer to as the Purple People Eater, but when Billy suggests they play “Purple People Eater” the Purple People Eater wigs out and tells him no; it’s not time yet.

A band named The Purple People Eaters that doesn’t play “Purple People Eater” is just marginally less stupid than a movie called Purple People Eater in which no people are eaten, but I don’t think Shayne realizes either of these things.

What does the Purple People Eater mean about it not being time to play “Purple People Eater”? I have no idea. Billy does suggest they open the set with it, so maybe his concern is that it’s too early in the show, and it would be better as an encore or something? It’s not clear. But the only time the band does play “Purple People Eater” is at the very end of the movie, when the Purple People Eater briefly becomes the Tasmanian Devil and then zips back to his own planet, which he never got around to telling anyone about and which the kids never expressed any interest in.

So maybe the idea is that playing “Purple People Eater” causes him, somehow, to leave, and that’s why he didn’t want the band playing it earlier in the film? I have no idea. Nobody has any idea.

Mr. Noodle announces to all the old people that they have to be out of their homes by Labor Day so he can turn the apartments into a puppy decapitation facility.

The Purple People Eater decides to host a Live Aid-style event called Save Our Seniors, intended to raise enough funds and awareness to keep them where they are. He schedules it for…Labor Day.

So, that would be too late, right? Fortunately for them, the movie forgets its own timeframe, and the old people are still in their homes the day of the concert. They must have some serious fucking faith in the Purple People Eater not to even box up their belongings after being evicted, but whatever.

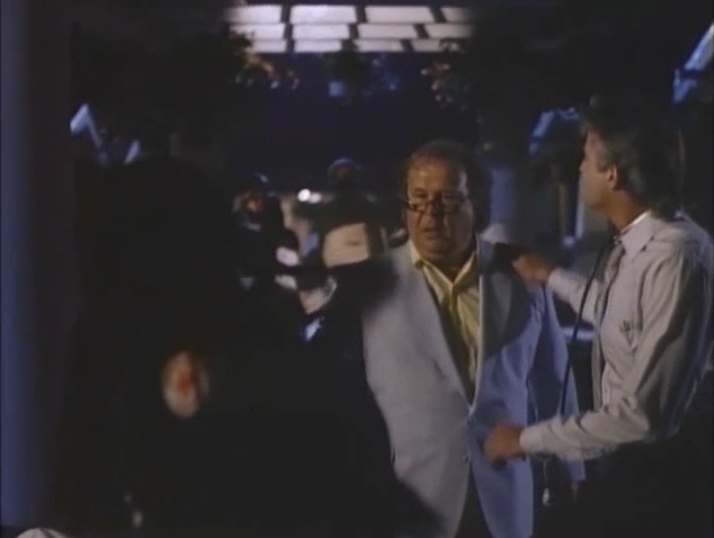

We learn that the Purple People Eater only sleeps hanging upside down in the shed so that Mr. Noodle can kidnap him. In their struggle they bump into a jukebox, which plays “Rockin’ Robin,” a surprisingly upbeat little ditty for a scene in which a real-estate mogul beats the hot shit out of a space alien.

He takes the Purple People Eater to Hide-Out Wallies, a good choice as it’s apparently the only bar in the world that closes at night.

Then Mr. Noodle takes a massive step beyond almost every other movie villain in terms of competence by not leaving his hostage.

I mean, the sight of this guy strapping the Purple People Eater to a pool table is every bit as disturbing as you’d expect it to be, but still, massive kudos to Mr. Noodle for not going home with the assumption that everything will turn out fine.

Of course, Labor Day morning comes and the Purple People Eater gets away by untying himself and leaving, a plan it evidently took him around 12 hours to come up with.

He then punctures Mr. Noodle’s tires with his horn, which looks about as sharp as my fingertip, but it doesn’t stop Mr. Noodle; he just drives the car anyway and the flat tire has no impact whatsoever on his ability to chase the Purple People Eater around.

The Purple People Eater steals someone’s ’55 Thunderbird and turns on “Rockin’ Robin,” which I think is because Shayne ran out of licensing money but which is extra funny to me because it seems like the Purple People Eater heard “Rockin’ Robin” while he was getting curb-stomped by Mr. Noodle and thought, “Man, this song is actually really good,” making a note to check it out later.

The fact that the Purple People Eater can drive a car doesn’t bother me. Actually, it does, but I want to stop writing about the movie, so let’s take that as read. But it does remind me that we never saw his spaceship. Did he even have one? How did he get to Earth without one? And if he did have one, where the hell is it? Is it just orbiting the planet with its hazard lights on?

And actually, the box art for the movie has Ned Beatty and Shelley Winters driving a car through outer space, which I’m suddenly deeply angry doesn’t happen in the film because we needed more scenes of them sitting on couches saying, “It sure sucks dick being old.”

While all this is happening, the kids and grandpa run around town, desperately searching for the Purple People Eater, because there’s no way they can play covers of early rock music without some midget in a Grimace costume twerking.

For no conceivable reason whatsoever, the Purple People Eater drives his stolen car into an automatic car wash.

This is seriously Mr. Noodle’s lucky day; all he has to do is drive to the exit and wait for…

Oh. Mr. Noodle is a fucking moron and drives through the car wash behind him, fully aware that they will both be moving at fixed speeds and that the Purple People Eater will have a head start when they’re back on the road.

Not that that matters, because the car wash malfunctions somehow. Mr. Noodle, you complete tit.

The police arrive not to arrest Mr. Noodle for kidnapping or to arrest the Purple People Eater for stealing a car or to arrest them both for destroying an automatic car wash, but to give the fucking space monster a police escort to Barely Alive Aid.

Come to think of it, even if they’re cool with him stealing the car, aren’t they concerned that he’s driving? They think he’s a 10-year-old in a costume. Who are these cops?

Purple People Eater builds to a climactic scene in which the entire town joins the Purple People Eater and The Purple People Eaters in a rousing singalong of “Purple People Eater.”

Oddly, for a climactic scene, nobody seemed to put any effort into making it. The editing is absolutely terrible, with characters “singing” without moving their mouths, and keeping their mouths closed while lyrics somehow come out of them. There are hard edits at various points in the song that clearly jam different takes together without regard for where in the song we actually were when we made the splice.

And, perhaps most strangely, nobody seems to fucking know how the song goes. Whenever we cut to someone in the audience singing, it’s like they’re reading a sloppily written line off of a cue card.

Even Little Richard seems like he never heard this song before, completely unaware of the cadence or melody.

Oh, did I not mention Little Richard is the mayor of this town? Neither did the movie, but that’s okay, because this surprise cameo is a genuine highlight.

Quite what Little Richard has to do with “Purple People Eater” I have no idea, but he’s here, and he’s not Little Richard playing Mayor Goodheart or something; he’s just Little Richard who is also the mayor.

Little Richard is a treasure and I will hear no words against him. He’s one of those rare entertainers that has endured as a figure of coolness throughout his entire career, and the dude is nearing 90 as I write this. He’s got a perfect mix of talent, quirk, and winking ridiculousness that makes him a perfect fit for a scene like this. Parents like him because they’re in on the joke, and kids like him because he’s a massive, silly presence.

He’s fucking great is what I’m saying, and as soon as he hears Mr. Noodle wants to throw all the old people out of their apartments, Mayor Little Richard takes a vote of all the concert attendees and declares it illegal for old people to be relocated ever, anywhere, for any reason, until the Earth is consumed by the sun.

It’s…not how local government works, but it’s just ridiculous enough that it’s the only scripted moment in the entire film that I enjoyed.

Actually, that’s damning with faint praise, so let me rephrase that: I enjoyed it so much that I genuinely wish every movie would end with Little Richard showing up and declaring that the film’s conflict is over.

The fact that Mayor Little Richard shuts Mr. Noodle’s shit down the moment he hears about it does sort of mean Save Our Seniors was thoroughly unnecessary and Billy or grandpa or Shelley Winters or Longfellow could have placed exactly one call to city hall and been done with this weeks ago, but there’s no time to think about that because the Purple People Eater is leaving forever.

Billy learned to believe in himself, I guess, and grandpa learned to…paint his house? And…

I don’t know. Nothing happened. The fucking puppet hiccuping was the most exciting thing in the movie.

But at the same time, it was kind of great.

There are a lot of bad films out there. You know that. I know that. Years ago we’d just have to walk along any given aisle in a Blockbuster Video, and today we only need to scroll through any given category in Netflix or Hulu to find hundreds of them.

They’re awful. They’re cash-ins. They’re complete wastes of time.

Until you find one that’s magical in its awfulness. One that makes you laugh harder than any comedy you’ve ever seen. One so monumentally incompetent you don’t tell your friends, “It sucked; don’t bother,” but rather plead with them to watch it because they wouldn’t believe how gloriously awful it is unless they saw it with their own eyes.

That’s what Purple People Eater turned out to be.

Harper Valley PTA was misjudged. Convoy was forgettable. Purple People Eater is a golden turd.

Almost nothing in this movie works, but everything fails in perfect harmony, creating a filmwide sort of anti-logic that manages to hold together in the strangest ways.

Characters appear and disappear. Plot threads are raised and abandoned. Non-issues are treated as calamities and serious concerns are brushed aside. The movie stops dead for several minutes so Chubby Checker, in what seems to be a fantasy sequence completely disconnected from anyone fantasizing, can lip sync to “Twist it Up.”

And it’s all just god-damned perfect.

I was interested this year in finding out whether or not a novelty song could be successfully adapted into a full-length feature film. Harper Valley PTA right out of the gate proved it could, at least hypothetically. But Purple People Eater proved it’s often much more fun to ride a moronic concept directly into the ground.

We are impressed when we see complex machines running smoothly, but damned if we aren’t far more fascinated by the one that explodes in brilliant flames.

This is a movie that is thoroughly enjoyable to watch fall to pieces.

I love you, too, Purple People Eater.