O my countrymen!–be nice;–be cautious of your language;–and never, O! never let it be forgotten upon what small particles your eloquence and your fame depend.

— The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman

Before we begin, this is your fair warning that this post contains plot spoilers for Far Cry: New Dawn. I can’t quite decide if I’d call them minor spoilers, so if you plan on playing it and believe any story-related spoilers would interfere with your enjoyment, bail now.

Okay.

I finished Far Cry: New Dawn recently, and I enjoyed it very much. It retained just about all of the best things about Far Cry 5 and cut huge amounts of fat. The result is a tight, focused experience that allows for plenty of freedom but also never loses sight of itself for the sake of providing more content.

I wasn’t quite sure going in whether or not I would encounter a sincere ethical dilemma at any point in the story. I hoped I would — as those are almost always my favorite parts of apocalyptic/post-apocalyptic games — but I was also fully aware that Far Cry, as a series, is about moment-to-moment action and bombastic thrill.

I did finally get my ethical dilemma toward the end of the game. It was a good one, but it was complicated in a way I didn’t expect and which I still don’t know how to process.

If you regret ignoring my first spoiler warning, consider this to be your last one.

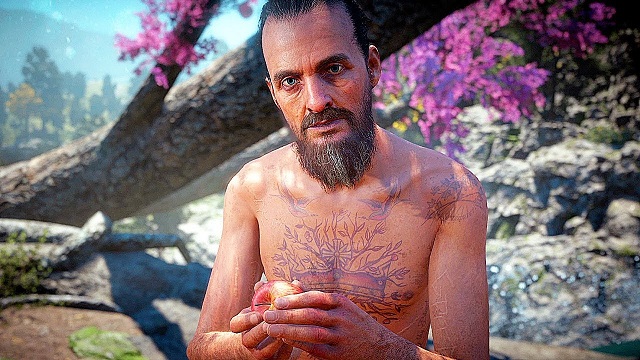

In Far Cry: New Dawn, you play as a different character from the one you played in Far Cry 5, but it’s a direct sequel — set around 20 years later — and you encounter a few of the same characters, including that game’s central villain, Joseph Seed.

In Far Cry 5, Eden’s Gate — his doomsday cult in rural Montana — is a genuinely dangerous force that commits atrocities against the residents of Hope County, which Joseph and his followers have seized.

Throughout the game you liberate the county inch by inch as you fight your way toward Joseph. When you finally do confront him, the distant explosion of a nuclear bomb vindicates his prophecy — though certainly not his methods. Doomsday was coming, and now it’s here.

In Far Cry 5, Joseph is very clearly a villain. You can argue that he’s charismatic. You can, ultimately, argue that he’s correct. But as a human being, the most slack you could possibly cut him is a willingness to believe that he’s a slave to severe mental illness.

He is not sympathetic, and any sympathy you could possibly feel for him is stripped away every time you see his followers gassing innocents, peeling their skin off, or executing them on the roadside.

That’s okay. There’s enough going on that Joseph Seed doesn’t seem one-dimensional, even if the game doesn’t complicate his role as villain.

In Far Cry: New Dawn, the game complicates his role as villain.

Here, the villain title — within both the game and its marketing materials — is usurped by Mickey and Lou, the twin leaders of a massive group of raiders called The Highwaymen.

Being as Joseph survived the events of Far Cry 5, the twins taking over as villains suggested two possibilities to me. Either Joseph is now reformed, or the twins are so terrible, his behavior seems tame in comparison.

Both of these things are true.

While Joseph and his followers behaved horrendously and absolutely did need to be stopped — in the face of a looming apocalypse or not — they operated by a kind of logic. Cruel, reprehensible logic, but as you take down his three “Heralds” who each control their regions, their individual motives and methods are clear. There is a kind of law — a clear system of transgressions and punishments — at work. The whip comes down for reasons you were explicitly told the whip would come down.

The twins, in sharp contrast, are wildcards. They behave every bit as terribly as Joseph and Eden’s Gate did, but they do so for the hell of it. There’s a bit of loose logic behind their actions (so loose it would only muddy the discussion to get into it here), but they are ultimately creatures of selfish impulse.

Talk back to them and they might smack you. Or kill you. Or kill your friend. Or kidnap your family. Or burn your settlement to the ground. They’re capricious. They’re unpredictable. And so while someone could — in theory at least — carve out a life for themselves within the strict and unforgiving doctrine of Eden’s Gate, nobody, at any point, could possibly be safe from the twins, because there are no rules. There is no system by which one can avoid punishment. When The Highwaymen drive by, you can do nothing other than hope that they keep driving.

So, yes, the twins are worse on a day-to-day basis than Joseph was.

And Joseph has also reformed.

He is no longer violent. He has abdicated his seat at the head of Eden’s Gate, and lives a life of simple, isolated humility. (Well…comparative humility.) The settlement he founded is the most successful one in post-blast Hope County. It’s self-sustaining, quiet, and peaceful. His followers have traded guns and fatigues for bows and cloaks. Unlike the Eden’s Gate of the previous game, which worked to actively conquer the land, the group now coexists with it. It lives in easy harmony with nature, far from the gunfire and explosions and chaos that dominate the map.

Before I even encountered Joseph in New Dawn, the game did a great job of making me consider my feelings toward him.

For starters, I had information my character didn’t. I saw Joseph in Far Cry 5, and I saw the atrocities committed in his name. My character in New Dawn, however, did not. My character sees the fruits of Joseph’s labor and not the blood with which they were fertilized. Enough people in Hope County survived the apocalypse that word of Joseph’s unforgivable ways still floats around, but damned if my character can see any evidence of them. In fact, at one point we turn to Eden’s Gate for help and…we get it. At great cost to their community, they help us defend ours against those who seek to harm us. Because I’ve seen both sides of that coin now, my feelings are complicated.

And so I eventually face the dilemma I should have expected.

I won’t get into the complete events of Far Cry: New Dawn because I don’t want to spoil things unnecessarily, but it’s enough to say that things don’t go so well. (It’s the post-apocalypse, for crying out loud.)

Joseph, alone in a remote cabin, frets for his soul. As certain of himself as he was in the previous game, he’s uncertain now. He isn’t sure he was ever a prophet. His faith in God doesn’t seem to waver, but his faith in himself sure as hell does. Almost two decades of reflection have him questioning whether the ends justified his means.

Far Cry: New Dawn expects us to have experience of Far Cry 5. Our character does not, and this contrite, damaged, tormented Joseph is all they know. But we know more.

So when we are given the prompt to kill Joseph, we recognize it as a bookend to the prompt that opened Far Cry 5 telling us to arrest him.

We didn’t actually have to arrest him. We had a choice. We could silently refuse. And we have that same choice now.

Do we kill Joseph?

What a great ethical question. Has he atoned for his crimes? He certainly seems sincere. Moreso than he’s ever seemed. He’s lost everything and asks for nothing. Could that be enough? Can we (and should we) leave an old man alone in the wilderness? Or should we remember that he was once a young man who did terrible things? Technically the same man and yet…they genuinely could not be more different now.

Isn’t capital punishment intended to remove from society someone who poses a significant threat to others? If Joseph no longer poses that threat, is it right to punish him that way? Perhaps his crimes should not go unpunished, but what about all the good he’s done in the past 20-ish years? He founded the only successful settlement, and he founded it on peace. Does that count for enough on the karmic scorecard?

All of this and more went through my mind when I realized I had the choice to kill him or to let him live.

But then it was complicated. And it was complicated by one word.

Here’s what the game’s subtitles told me he said:

My soul has become a cancer. I am a monster. And I only spread suffering and death in the name of God.

Here’s what actually came out of his mouth:

My soul has become a cancer. I am a monster. And I have only spread suffering and death in the name of God.

Note the word “have.”

I’ve seen plenty of discrepancies between what a voice actor says and what a subtitle tells me they are saying. It happens. Sometimes they skip a word without realizing it. Sometimes they smooth a sentence out because what looks fine in print doesn’t always sound right when spoken aloud. Sometimes they find a certain quirk or vocal tic in the character that affects how they say things in a way that isn’t actually reflected in the script.

And all of that is fine. Actors across all media — and even singers with their own songs — change the words a bit, deliberately or not, when it comes time to perform.

But that one word — Tristram Shandy’s small particle — completely changes the meaning of Joseph’s confession.

If I were only reading the subtitles, I’d conclude that Joseph is upset because he continues to be a rolling source of disaster. If I were only listening to his voice, I’d conclude that he’s upset because he has caused so much disaster in the past.

One of those things might deserve mercy. One of those things might not. One of those things abandons responsibility to a cosmic absolute. One of those things accepts responsibility.

And, in a case like this, I’m still not sure — several days after I made my decision — quite how to handle that self-negating information.

Was the subtitle an error in transcription? Was the voice actor wrong and nobody caught it? We could, in theory, turn to the original script to find out, but does it even matter what’s in the script if it doesn’t reflect what the character actually said?

We’ve all misspoken, and while our intentions undoubtedly matter, are we not still responsible for the things that actually come out of our mouths? Don’t our actual words — whatever we meant to have said — shape the way others see us and respond to us? And…shouldn’t they?

There’s no chance Far Cry: New Dawn did this deliberately (if this were Nier: Automata, for instance, I wouldn’t be so sure), but in this moment, we get both versions of Joseph Seed, coexisting.

In one voice, it’s the old Joseph, the fount of continuous destruction. In another voice, at the exact same time, it’s the new Joseph, distanced from who he used to be.

I have very different feelings for each of these Josephs. I imagine I can’t be alone in that. And what was either a four-character omission by someone at a keyboard or an actor’s slip of the tongue that went unnoticed holds a character’s life — and his future, and the future of Hope County — in the balance.

The reason I love ethical quandaries in games is that they force me to think about them, to process them, to react to them, to learn more about who I am based on how I respond to unclear moralities. They make me more aware of what I think.

This one I ended up loving because it reminded me, unintentionally, to be more aware of what I say.