My intention with this year’s Rule of Three, as you might have guessed last week, was to spend some time up front discussing context, discussing the creators, discussing what the YouTube channel behind the film is known for. My reason for this is that the films we’re covering are labors of love first and commercial products second. (Or third. Or fourth…)

I went into this series not knowing if I’d enjoy any of the films. If I did, great. If I didn’t, however, the last thing I wanted to do was launch directly into a tirade against something that someone I respect put a lot of work into. I’d be honest, of course, but the least I could do was celebrate their achievements up front. Their appeal. Their ability to amass an audience in the first place.

But I’m not sure if I can do that with Space Cop, so allow me to put my opinion up front. Ready?

Thanks to Space Cop, I think I finally, truly understand the term “guilty pleasure.”

I’ve long known that term, of course. I’ve probably even used it, though until this point I never meant it.

The thing is, I like crap. I know that and I’m comfortable with that. The Room isn’t a guilty pleasure for me, because I feel no guilt about the pleasure it brings me. I love the pleasure it brings me. Ditto Miami Connection, Santa and the Ice Cream Bunny, and what I truly hope is the ever-growing filmography of Neil Breen.

As little genuine merit as those things contain, I feel no guilt about my love for them. I share them with friends. I excitedly seek out films with even less merit. I set time aside to watch them because I enjoy watching them.

Guilt never enters into it. It can’t. My love is genuine, even if it takes a different shape from the love I have for the truly great films that have moved me, inspired me, defined who I am.

Then I watched Space Cop, and I think I get it. It still might be a bit much to say that I feel guilt for loving it, but I am at least compelled to couch my love for the movie in apology. With admissions that it isn’t great. With the understanding that I am and will continue to be an outlier.

That may not be fair to Space Cop. It may also be the fairest possible way in which a human being can love Space Cop. To explain that, though, we’ll finally need to arrive where I thought this review would begin: with a discussion of Red Letter Media.

Red Letter Media as a channel is primarily focused on film criticism, with few excursions into other media. The three founders — Mike Stoklasa, Jay Bauman, and Rich Evans — started posting videos in 2007, which were mainly short films and low-budget experiments to keep themselves and their friends entertained. That’s okay.

Then, in 2008, the channel found a direction. Stoklasa — annoyed at a film that released 13 years earlier — created a longform video essay about Star Trek Generations. Rather than review it, y’know, normally, he assigned it to a character: Mr. Plinkett. Stoklasa affected a low, droning voice and didn’t appear on camera. Giving the review to a character meant that he got to write for a character, which itself led to jokes and ideas that probably wouldn’t have worked if he’d presented himself as nothing more than A Guy With An Opinion on the Internet.

From there, he — as Plinkett — covered the rest of the Star Trek: The Next Generation films. Then, in 2009, he decided to have Plinkett review Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace.

This is when everything changed for the channel.

With four film reviews under his belt, a better understanding of his Plinkett character, and two friends still itching to produce more short films, he turned his Phantom Menace review into an event. For around 70 minutes, Stoklasa narrated a work of criticism that doubled as a comedy film in its own right, with elements of documentary and horror parody woven throughout.

The fact that it’s still so difficult to explain is a testament to just how unique that review is. Like Rolfe with his Angry Video Game Nerd character, countless people have attempted to duplicate it superficially, but nobody has really come close to recreating the magic underneath.

The Phantom Menace review was intelligent and insightful enough to earn Stoklasa fans in the film industry who were equally disappointed by how the movie had turned out.

He focused on larger issues in the film’s structure, production, and writing than on the more obvious missteps, such as Jar Jar Binks being a thing that existed in a major motion picture. That alone gave his review an air of legitimacy, elevating it well above the typical level of internet discourse. Combined with genuinely funny jokes, sharp observations, and the bonkers framing device of murderous monster Plinkett ranting about a long-ago-dismissed Star Wars film, Red Letter Media found itself with a worldwide audience overnight.

With an audience came expectations. Stoklasa, Bauman, and Evans rose to meet them.

The channel’s legions of new subscribers weren’t tuning in to see three friends screwing around with a video camera. A unique work of film criticism drew them to Red Letter Media, and Red Letter Media in turn started providing unique works of film criticism more regularly.

They introduced a number of shows over time. Half in the Bag featured Stoklasa and Bauman as VCR repairmen (and Evans as Mr. Plinkett, their recurring customer) who discuss — usually — recent releases. Best of the Worst sees a rotating panel including those three and a few other friends who watch movies they — usually — have not seen and then discuss them. Re:View stars two people discussing a movie they either already enjoy or have enough to say about that it warrants a dedicated conversation. Plinkett reviews continued, of course, and various other projects came and went.

The best of these was and remains Best of the Worst, which is probably my favorite show that’s ever come out of YouTube. It captures the giddy thrill of discovering terrible films with like-minded friends, and the resulting panel discussions range from fascinating and insightful to digressive and absurd. It’s a bit of an acquired taste, probably, but if you’ve ever spent a night watching bad movies with close friends and a case of a beer, it will feel familiar.

It also, I think, shows off the best aspects of the channel; the panelists bring a wealth of film knowledge, some degree of film-making experience, and great comic interplay that makes their discussions enriching and entertaining by turns, even if you don’t care about a single thing being discussed.

All of this is to say that — by every possible metric — Space Cop had the most to prove.

If James Rolfe or Stuart Ashen failed to make entertaining films, those movies would register exclusively as failed experiments.

Stoklasa, Bauman, Evans, and their collaborators, though, built their brand on some degree of expertise in this arena. None of them, I’m sure, would claim to be a master of their craft, but they at least present themselves as being in a position of relative competence. They regularly and consistently dissect films that have gone wrong and propose corrections.

With Space Cop, it was their chance to put theory into practice. It was also their chance to embrace once again their love of film production, this time with years of experience of movie criticism behind them. Surely whatever they made would have to be good.

Surely.

These film lovers, these movie buffs, these students of the medium, these preeminent voices who redefined the way amateur critics present themselves and their opinions, made a movie about an outer-space policeman who travels through time.

It feels (pardon the pun) like a cop out. There is no doubt in my mind that this particular creative team could put together a film worth taking seriously. It could still be a comedy, of course. It could be anything they wanted it to be. It could be a love letter to the great films that inspired their passion.

Instead, it’s a riff on some of the worst movies ever made. And that feels — correctly or not — like a barrier to criticism. Did you think Space Cop was bad? Well, it was supposed to be bad so, hey, big deal. If Stoklasa and co. could hide behind the pretense that they weren’t taking it seriously, they could also shrug off the criticism of anyone who did take it seriously.

I — a fucking idiot on the internet — believe that that was the wrong decision, because I think they could have achieved something of decent merit with their combined talent, knowledge, and experience.

But I didn’t get whatever else they could have produced together. I got Space Cop.

And I loved it.

This is where the guilt comes in. They could have delivered more, and I wanted more, but we ended up with this gleefully stupid pastiche of buddy-cop films, and I adored almost every second of it.

When I reviewed Deathrow Gameshow, I said that it was frequently dumb but never stupid. Space Cop is endlessly, bottomlessly, unapologetically stupid. It relishes its own stupidity, to the point that stupidity becomes a kind of language that it is speaking, a language in which it reveals itself to be fluent.

I could pull it apart. I could point out all of the things that don’t work, even on the film’s own terms. I could painstakingly detail the ways in which Space Cop holds itself back. Actually, that sounds like a great idea; I will do all of these things. But — and this is important — none of that matters. At all. Because even at its roughest, its shaggiest, and its weakest, Space Cop is brilliant in its stupidity.

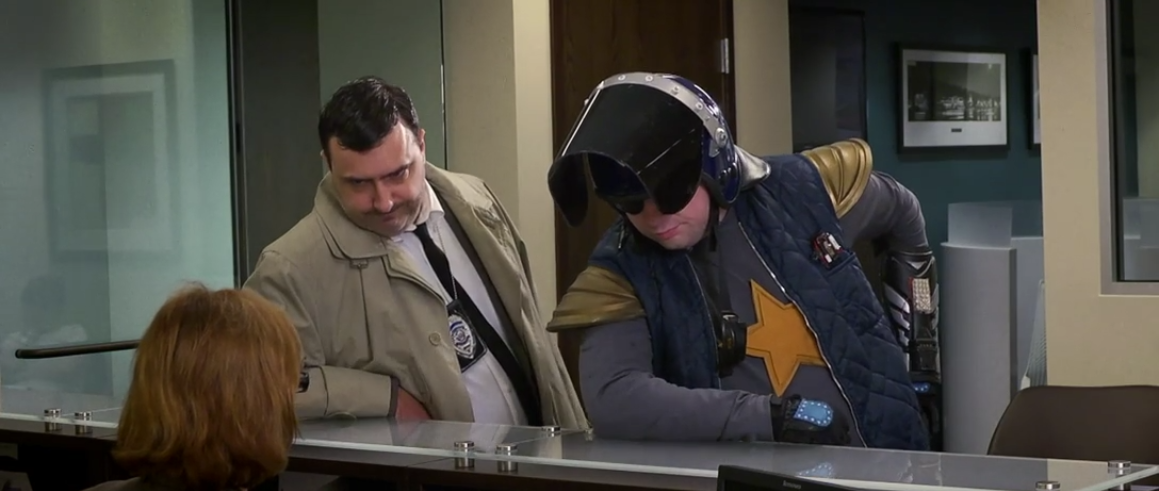

The film stars Evans as Space Cop, a futuristic policeman who is accidentally hurled backward in time to present-day Milwaukee. Where he again becomes a cop. He eventually teams up with Stoklasa, who plays Ted Cooper, a cop who was frozen in the past and is unthawed in present-day Milwaukee. Where he again becomes a cop.

It’s impossible to summarize any aspect of the film without it sounding ridiculous, and you can probably guess why that is.

Evans plays Space Cop as a gruff, grumbling tough guy with absolutely no sense of self-awareness. He’s an imbecile, a slob, and a boob who believes himself to be — against all evidence — an unstoppable force of sheer badassery. And yet even when he does succeed and receive recognition for his achievements, he’s surly and dissatisfied. He’s a completely unlikable person and, debatably, no attempt is made to redeem him in the audience’s eyes.

That sort of character sounds tedious, and usually is tedious. Space Cop may be the only truly unlikable character that I’ve ever actually liked, however. He doesn’t soften as the movie progresses, he is not redeemed, and he ends the film bitching about nobody appreciating him immediately after the city of Milwaukee holds a celebration in his honor. But I love him.

I’m sure some amount of this is down to the writing, but most of the credit belongs to Evans. Within just about every Red Letter Media production, Evans is the funny fat guy. The chubby funster. He’s in on the joke; whenever we’re asked to laugh at him, he’s ahead of us, already laughing at himself.

He’s a figure of fun who manages to have most of the fun himself. He is innately likeable, and that’s the key to a character like Space Cop. A film has every right to give us a shitheel protagonist, but that film has to either be okay with us hating him or give us, at some point, a reason to reconsider how we feel about him.

Or it could cast Rich Evans.

It’s impossible to hate Evans, because even as he gives Space Cop (and Space Cop) his all, he’s such a fun presence. You don’t catch him smirking and winking his way through the film; he plays Space Cop exactly like the piece of shit that the character is. But there’s a kind of cuddly magnetism to the guy wearing the ridiculous costume that keeps things just detached enough to stay funny, no matter how awful a human being Space Cop is.

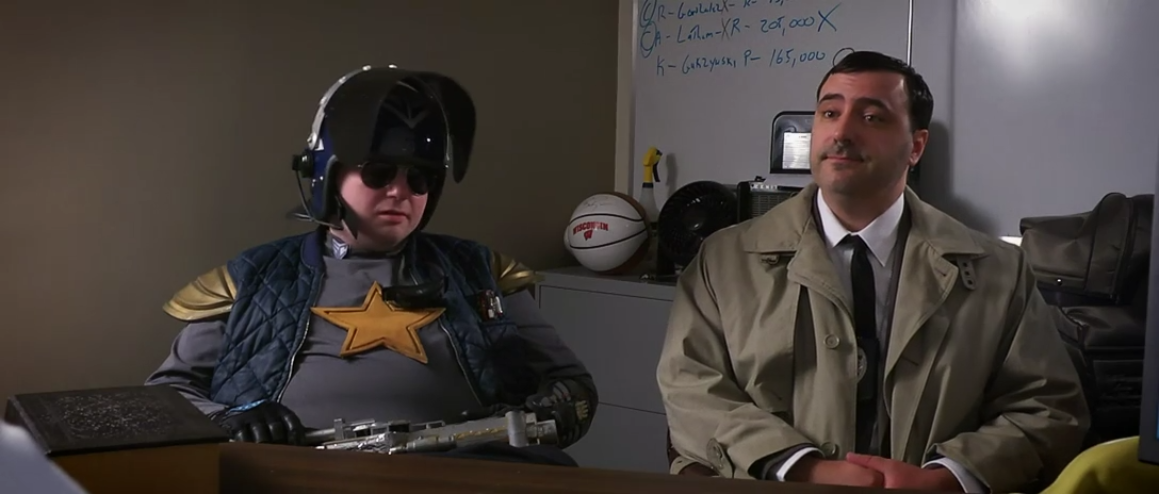

At first I was puzzled as to why Stoklasa wasn’t playing Space Cop, with Evans as the cheerier sidekick. Ultimately, though, as much as I like Stoklasa, I suspect he would have been a bit too believable as a grumpy misanthrope.

Evans is cast against type, basically, which ends up being a joke in itself. And that leaves Stoklasa — Red Letter Media’s resident souse and the endlessly griping voice of Mr. Plinkett — to play the chipper, can-do character of Ted Cooper. He’s no better a fit for his character than Evans is for his, which is exactly why he works just as well.

Stoklasa is a natural sourpuss, so seeing him in the role of the optimist is funny. Evans is naturally jolly, so seeing him as an emotionless hardass is funny. But that’s not quite enough for a film; I think we can all agree on that. And Space Cop sometimes fails to take the joke beyond the inherent comedy of these characters existing.

Throughout the movie, I kept wanting things to drift into more familiar territory, if only because there was so much potential there. The movie even butts up against that potential a few times.

Both of our main cops are out of their elements. Space Cop has experience of the job that no longer applies and Ted Cooper has experience of the job that no longer applies, and their experience doesn’t overlap. They should be struggling to fit in at the same time that they’re struggling to fit together. That’s what a movie with this premise should do.

Instead, we get little more than token nods to the characters having to adjust their methods. Space Cop’s ultraviolent solutions don’t fly in present-day Milwaukee any more than Ted Cooper’s casual sexism and racism do, but those things rarely surface for anything more than a couple of lines or a scene. It’s the barest of lip service paid to what would be the defining characteristics of these people if they existed in anybody else’s version of the film.

But I think that’s okay. What’s more, I think that’s deliberate.

I think I’m supposed to want a story like this to unfold according to a predictable formula. I think I’m supposed to anticipate story beats that either don’t arrive or that look quite different when they do arrive. I think, basically, I’m supposed to let the film tell its shaggy dog story, because it’s the loose, meandering style of the comedy that matters.

And when you do let the film take you in its own direction, it’s funny.

What seemed to be one of the movie’s strangest choices ends up being a key to understanding it. After Space Cop is hurled backward in time, we see him awaken. He stands up. He surveys his surroundings. He sees that he is trapped in the past, in a city he both knows and does not know, in a world that does not know him at all.

We then jump forward eight years and see that Space Cop is exactly as we knew him from the future. He’s a boorish putz, sick of the world around him and the people who occupy it, dissatisfied with his job, and uninterested in improving himself or his situation.

That narrative time jump — occurring immediately after Space Cop makes a literal time jump — baffled me. Couldn’t writers Stoklasa and Bauman have come up with anything for Space Cop to do in those eight years? Couldn’t they have come up with jokes about how he tries to fit in, how he grapples with outdated technology, how he adjusts to life in another time?

Again, that’s what a movie with this premise should do.

And I’m sure Space Cop went through all of that. I’m sure Space Cop was confused by doors that didn’t open on their own and cars that didn’t fly and a moon that wasn’t colonized…but we didn’t see any of it, because that’s not the story Stoklasa and Bauman wanted to tell. All we need to know is that whatever else Space Cop got up to in the intervening years, he ended up being exactly what he was before: a miserable piece of shit police officer.

Space Cop had a life he hated, then got a chance to start over fresh. Eight years later, his choices put him precisely where he was when we first met him…only displaced in time a bit.

It’s an excellent unspoken joke, and that eight-year time skip that drove me nuts at first now feels to me like a stroke of genius. It might be the only time I’ve seen someone attempt characterization by use of negative space.

There is a story to Space Cop, and it actually does unfold with some kind of recognizable logic, but the comedy — correctly — comes almost entirely from Stoklasa and Evans interacting. That makes it a bit unfortunate that Stoklasa’s character takes a while to show up, but that may be a symptom of poor pacing early on.

Essentially, the film introduces Space Cop twice. First, we see him in his element, dealing with a hostage crisis that ends in unnecessary violence and collateral damage. Later, we see him in our element, dealing with a hostage crisis that ends in unnecessary violence and collateral damage. The comic doubling is clearly deliberate, but I’m not sure how necessary it is to have both scenes, especially when all they really do is scoot the proper start of the film further and further back.

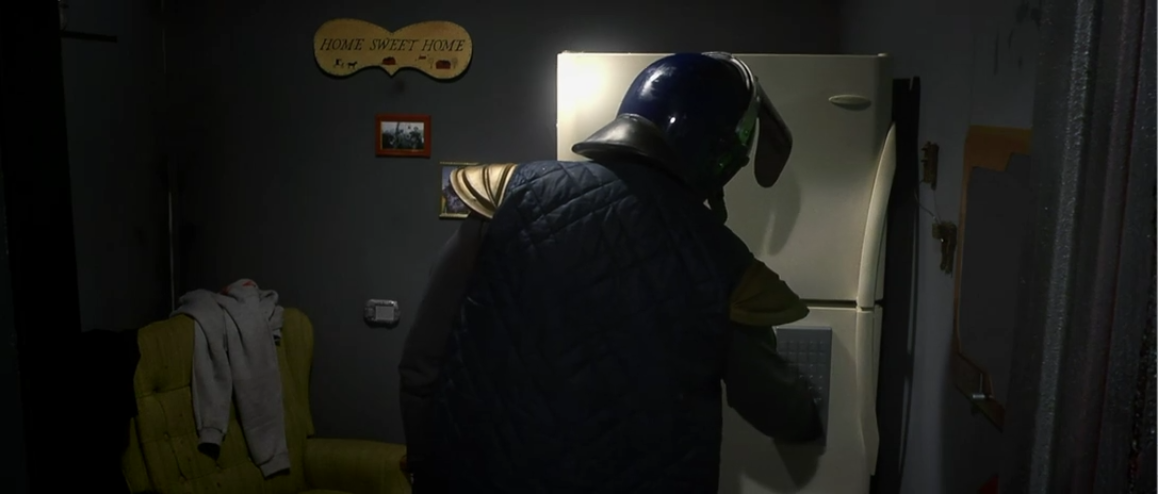

In between those two introductions, we get a long scene in Space Cop’s apartment that features two distinct stretches of endurance humor.

I like endurance humor, but I have to admit that sitting through two occurrences of it — sandwiched between two introductions to the same character — when you’re still waiting for the movie to get going is a bit much.

For those who aren’t familiar with the term, endurance humor refers to the comedy of things deliberately dragging on for too long. See Peter Griffin grasping his knee in pain, or Eric Idle monologuing endlessly at Michael Palin’s travel agent. The joke, essentially, is less about what’s happening than the fact that you in the audience are sitting through it.

The better stretch of endurance humor here is Space Cop opening his refrigerator, a process that requires Evans to punch button after button on a keypad long enough that we understand the joke and then just long enough more that it threatens to overstay its welcome. He then opens the refrigerator into his table, which falls over, in a perfectly timed visual punchline that we didn’t even realize was being built toward.

It’s executed well, and it’s a nice bit of ridiculous future technology that is funny for the mere fact that it exists.

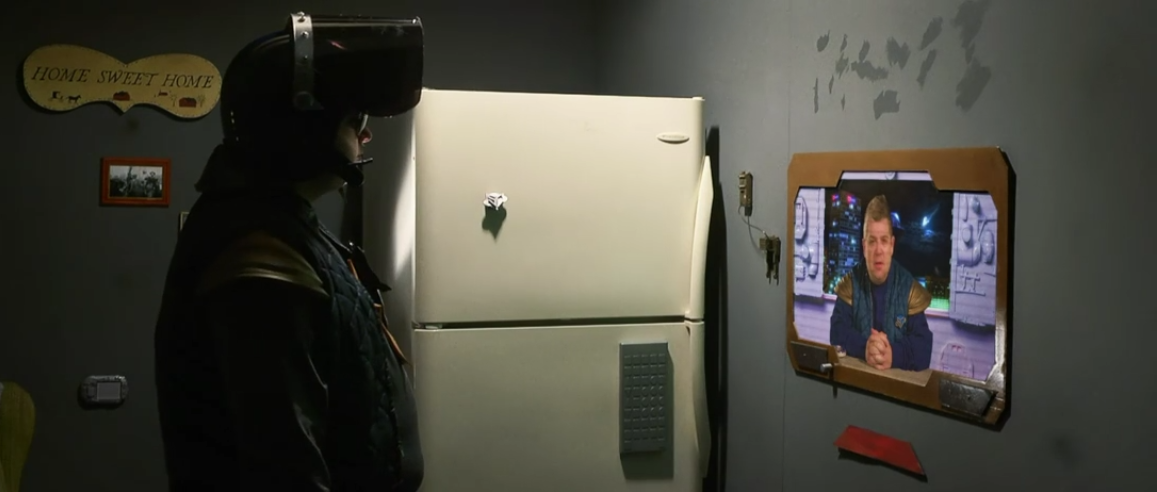

This is followed by another stretch of endurance humor, though, in which Patton Oswalt — as the chief of the Space Police — places a video call to Space Cop, speaks with Space Cop, and then can’t figure out how to end the call to Space Cop. Space Cop stares blankly at him the entire time, and there’s no real punchline.

I understand what happened. Oswalt is a celebrity. Red Letter Media got him to appear in their film, and they were understandably proud of that fact. Oswalt riffed and Red Letter Media was reluctant to cut any of it. Because, hey, it’s Patton Oswalt in their movie, and he’s giving them material. Why not use it?

Well, for a number of reasons, but I’m sure I’d struggle when faced with the same temptation. I’m a nobody making a movie, and a celebrity just handed me an extended joke that’s mine all mine. Whether or not it fits the scene as I’d imagined it, it would be difficult to talk me out of using it.

Stoklasa and Bauman could have cut most of Oswalt’s shtick and the scene would have been better for it. (Their film would have been tighter as well.) Or they could have cut Space Cop’s refrigerator antics, but I think they realized — correctly — that that was the funnier bit. So they ended up keeping both, causing the already bloated introduction of their film to drag even more.

I’m also not entirely sure of the decision to make Space Cop a dunce and a lout in his native time period. I think the character would work a bit better if the more obvious flaws in his police work — a reliance on technology, a propensity for violence — were commonplace in the future. We should see them as flaws, certainly, but I think his colleagues in the future should have reflected the fact that this is what police work in itself has become.

Instead, Space Cop is demoted to Space Traffic Cop for his carelessness, suggesting that other Space Cops are more competent and reliable than he is. Which, in turn, makes him a poor representative of the future.

But even that, I’m sure, is part of the joke. I’m just not sure if it’s a joke that helps or hinders the film overall.

Like Angry Video Game Nerd: The Movie, Space Cop hurls out idea after idea without always giving them the appropriate time (and, ahem, space) to land. Unlike that movie, though, Space Cop establishes its reality as elastic.

Angry Video Game Nerd: The Movie took place in our reality with our history. Rolfe and his cronies introduced some fictional elements to what he know to be true, and then used those fictional elements to bring to life a conspiracy. In short, it’s like most works of fiction: It takes place in a world we recognize, but with fictional characters having a fictional adventure.

That caused it to unravel whenever Rolfe steered the film into territory that is not recognizably of our world, whether it’s a vehicle exploding because it ran into a pane of glass, the AVGN projectile vomiting, or the strange Super Mario Bros.-inspired home-security sequence that I’m sure only exists because someone involved with the production remembered that the movie was supposed to have something to do with video games.

Space Cop, wisely, does not take place in our recognizable reality. The title character is from an imagined future, his sidekick is from an unseen past, and the present is presented (forgive that) as an amalgam of buddy-cop (has anyone made a film called Buddy Cop yet?) cliches and expectations. This film’s “reality,” in other words, is one we already recognize as fictional, because we’ve seen it exclusively in other films that we can’t take seriously.

This allows for some of the best stuff in the movie.

One of these things is Dale Jackson as Chief Washington. Modeled on Cameron Mitchell’s performance in Hollywood Cop, the specific recognition gets an extra chuckle. But everyone else has seen precisely this character giving precisely these speeches in precisely this context. It’s such a clear indication of how little we’re supposed to take what passes as reality in this film seriously. It’s also funny that he keeps Space Cop on the force only because Washington has stock in their insurance company. A lesser film wouldn’t have even thought to make that joke.

Another of these things is the exposition about Space Cop’s wife, who was killed by somebody out for revenge. “In the future, my wife’s dead,” Space Cop tells Cooper. “In the past, she’s not even born yet.”

That in itself is a concept that other films in this vein would treat seriously, but in Space Cop the mere fact that these two characters are having this conversation is hilarious. Simply mentioning backstory like this works as a joke when you’ve structured your absurd movie well enough.

Obviously, Space Cop has an opportunity to rewrite history. And he takes that opportunity during a long sequence that sees him driving drunkenly to the home of his wife’s killer — a nine-year-old boy at this point — and trying to murder him.

There’s narrative logic at play here — Space Cop is neither the brightest bulb nor the best shot — but really it’s an excuse for Evans to wear a ridiculous costume and shoot at a child who is desperately trying to get away. In the process of attempting to right a future wrong, Space Cop kills the kid’s father and causes the kid to get crushed by a train.

It’s absolutely stupid, but the sheer length of the scene and Space Cop’s inability to see that he is creating the reason for revenge that will get his wife killed is marvelous. (I could do without the scene during the end credits that spells this out for us. We get it. Nobody watching could be nearly as dumb as Space Cop.)

Then there’s Cooper, whose character arc should see him reconnecting with the wife and kids he left behind in the past, or at least attempting to find them and learning what’s happened to his family. And that does happen! Off camera. At some point. And it’s dealt with in the space of a sentence or two during the ending with a great handwave.

“We didn’t forget,” the moment seems to say. “We just don’t care.” And that was one of the biggest laughs in the entire film for me.

With few exceptions (such as the movie’s lone fart joke), just about every bit of comedy in Space Cop at least gets close to working. Often, to be clear, it works excellently. Other times, you can easily imagine a version of the joke that works just a hair better. Rarely does a joke land with a complete thud, though it stands out when it does.

At one point, Space Cop and Cooper visit a strip club. (You’ve seen these movies. Of course they visit a strip club.) An alien in human form takes the stage, played by Jocelyn Ridgely, who I only later learned appeared as Nadine in Mr. Plinkett’s Star Wars reviews.

She’s dressed inappropriately for a stripper, which is funny enough, and then does a bizarre sort of tremoring dance in front of our heroes. Clearly she thinks this is what human strippers would do, and just as clearly she is wrong. It’s a sequence that feels like it should be much funnier than it is, and I have a hard time figuring out why it isn’t.

I think, ultimately, it comes down to either the blocking or the editing. The dance is funny, but the presentation of the dance fails to help it feel funny. It does build to a moment in which Space Cop tears her face apart with his fingers so…okay, that checks out.

But it does feel a bit like Stoklasa isn’t able to give his supporting actors the same spotlight he’s able to give himself and Evans.

Another scene might illustrate this even better. Cooper visits Dr. Snodgrass to try to figure out the aliens’ plans. Both Cooper and Snodgrass are comedy characters, but only Cooper’s lines really feel funny. I don’t think this is down to any weakness in Bo Johnson, who plays Snodgrass. I honestly thought he was one of the better actors in the film, but nothing he says feels as funny as it should.

Cooper, on the other hand, gets almost every line to hit like a punchline. “Doctor, I don’t understand a single thing you’re saying,” Cooper tells him, “and that’s your fault.”

That hits in a way that you want all of this dialogue to hit, but outside of Stoklasa and Evans, it almost never does.

Perhaps they’re just not sure of how to bring other characters — characters they themselves do not play — to life. This might even be supported by the comic success of the Chief Washington character; they’re familiar enough with that type of role, and so they do know to frame the shots and present it in a way that every bit of business lands correctly.

Bauman shows up in the film as well, playing another one of the aliens, and he’s good with what he gets to do. That’s surprisingly little, though; I expected a much larger role for him, but seeing him briefly is certainly better than seeing him crammed into scenes that didn’t need him.

The film builds — as all great films do — to an intergalactic showdown, during which Space Cop, Cooper, and Ridgley’s alien try to stop a brain in a jar. The movie gets dangerously close to taking itself seriously…and maybe it actually does. At least in a sense.

Space Cop branches here, with Cooper and Ridgley taking one path and Space Cop himself taking another.

Cooper and Ridgley work together to figure out a way to disable the spaceship, helping Cooper to realize that his understanding of women as inferior creatures is outdated and unfair. There are jokes here, but not many of them. It’s played exactly the way you’d see this played in any other movie.

On the other branch, however, we have Space Cop being Space Cop. (Which allows Space Cop to keep being Space Cop.) While the other two characters put their heads together and attempt to find an intellectual, non-violent solution to the problem, Space Cop roams the ship’s corridors, beating the living shit out of everything he sees.

In one particularly great moment, he meets Bauman’s alien, who explains to him that all they are trying to do is save their planet. Space Cop, in a rare moment of understanding, tells Bauman that they should have just been clear with that up front, and he wouldn’t have fought them.

“I’m not a monster,” Space Cop says, and he may even believe it right up until he’s finished speaking that sentence, at which point he blasts a hole into space that sucks Bauman to his death.

It’s great because I believe both bits of Space Cop’s personality in that moment. He doesn’t think he’s fucking awful even as he’s demonstrating beyond the shadow of a doubt that he’s fucking awful.

Eventually he even saves the day by punching a brain to death. (Actually, Cooper and Ridgley saved the day, but then Space Cop un-saved it and saved it again in a much dumber Space Cop way.) I honestly cannot think of a more appropriate climax for the film, and though I sincerely mean that as a compliment you are welcome to see as much backhandedness in it as you like.

I love Space Cop for what it is. I don’t think it shows the extent of the Red Letter Media team’s talents, and I wouldn’t dream of recommending it to someone as their first experience of these guys, but it’s a sincerely funny film that knows exactly how to regulate its stupidity. It drifts near enough to the structure of other films that we know what it’s doing, but stays reliably in its own little realm of absurdity.

Space Cop feels like a trip into somebody else’s mind, where much of the fun is in figuring out just how these thoughts are connected and how everything works. It’s not the movie I would have made, and it’s not the movie I would have hoped Stoklasa, Evans, and Bauman would make, but it’s a fascinating window into the love this little team has for awful, awful movies.

It doesn’t deconstruct genre tropes intelligently, it isn’t all that sharp in its parody, and it really doesn’t say much at all. But I think that’s kind of the point, and right or wrong, the team bet on the appeal of that point.

Red Letter Media gave us a satire that doesn’t satirize anything. And while it’s far from perfect, once you get over that hump of expectation, you have a comedy that’s successful more often than it’s not, with some of the most genuinely funny stuff I’ve seen in a film in years.

I think they could have made a great movie. Instead, they made Space Cop.

Maybe that’s the film’s best joke.

I appreciated your honest review of this movie. I have not had the opportunity to see it, and don’t know if I ever will. But I’m fascinated by Red Letter Media and their content, and they bring a lot of joy to my life. Maybe I’ll buy it if they release it on VHS.