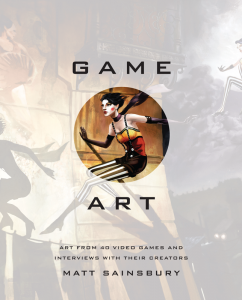

Releasing next week, Game Art is a directly-titled look at one of the most indirect forms of art out there. In fact, if I wanted to take issue with the book, that’s where I’d point; the title’s simplicity almost seems to do a disservice to the depths plumbed within.

Releasing next week, Game Art is a directly-titled look at one of the most indirect forms of art out there. In fact, if I wanted to take issue with the book, that’s where I’d point; the title’s simplicity almost seems to do a disservice to the depths plumbed within.

To put it as succinctly as I can: I very much enjoyed this book. So much so that it took me several weeks to write this review. It’s easy to get drawn into, and when you manage to pull yourself away there’s so little that it feels like one can add to it. It’s a perfect study of a traditionally unstudied medium, and it’s hard to put any of this better than the author — or his interviewees — already did.

I received a review copy from Matt Sainsbury himself. I mention that by way of dual disclaimer. Firstly, I got the thing for free, which is always good to know…but by this point I hope you realize how much I hate all things, generosity included, so that wasn’t about to shape my opinion. Secondly, I know Matt. But I know Matt, primarily, as a writer. As a critic. As someone who has been doing exactly what he does in this book for the past several years. If my opinion of Game Art is enhanced in any way by my knowledge of Matt, it’s because his body of work has earned that respect.

Game Art feels like the culmination of a passionate lifetime of independent study and appreciation. It’s an oddly magical journey that gives respectful, gallery treatment to the kind of art that so frequently flits along in the background while somebody tries to survive a gauntlet or solve a puzzle. And it’s pretty incredible stuff.

Quite why game art (lowercase) gets the short shrift, I’ll never know. It’s in the same boat game music was in a few decades ago; creations by talented people that were not perceived as legitimate works. In the case of game music, the rise of OverClocked ReMix did much to grant retroactive legitimacy to these compositions. It provided a platform for other artists to pay homage to and develop upon the source material, and it opened a path to reappraisal and rediscovery.

Game art, oddly, has not had the same opportunity. As graphics improve massively year over year — and as games are often derided for not looking good enough — there’s a stunning lack of appreciation for those images as art. They’re a box to be checked, and then the world moves on to judging the next one against some cold, arbitrary scale.

Matt opens the conversation for reappraisal with Game Art, quite literally. Because in addition to presenting some stunning imagery, he gets in touch with the artists and game designers that put these visuals together, and does something unthinkable: he asks them to talk about it.

The result is a guided tour through underappreciated works by those who labored to create them, and there’s an overriding and charming sense of humility in the words of just about every interviewee. These aren’t artists who demand to be noticed or even understood. These are creators speaking about their processes of creation, and it’s a beautiful read.

In fact, the book could have functioned perfectly well in either of two ways. It could have been a big, glossy, quiet showcase of in-game and concept art worthy of a second look. It could also have been a collection of interviews with the unsung artists behind the games we love and a few we’ve forgotten.

Instead it’s both, which is why it’s so hard to put down. Read a few interviews, and get lost for minutes on end in the companion visuals. Find an image that draws you in, and dive immediately into the words of the artist who created it. It’s not just a great way to understand and experience game art; it’s a companion to itself.

Most importantly, familiarity with the games themselves isn’t necessary to appreciate the book. While I’ve played a few of the games covered here, I can safely say that I missed out on the majority. The conversations, though, are about larger topics. Like these comments from Michael Samyn, who has five games featured in the collection, regarding the somewhat limiting interplay between his role and the programmers’ in putting a game together:

If you want to get really creative, you’re up against a wall all the time thanks to the rigidity of the programming. Artists have very complex logic of their own; it’s just that their minds work differently than a programmer’s. I do think that’s perhaps another reason there aren’t as many interesting games from an artistic point of view.

He then goes on to discuss a — potentially exciting — aspect of artistic design that’s very specific to an interactive medium like video games:

The player not only has the imagination to complete the work, as they would with a movie or book, but they can actively change the narrative itself. We also like to make our games rich so players can express themselves and do things depending on how they feel. That means we can’t really finish a game like you would finish a book or a movie.

These aren’t conversations that require a specific frame of knowledge to understand; these are unique and valuable insights into the nature, obstacles, and experiences of the creative mind.

Game Art is at once an easy read and deceptively dense. It’s difficult to speak concretely about it, because much of what the book does is get your own mind working. When, as above, a question of leaving room for audience interplay is raised, it’s conducive to independent thought. It gets your mind working as a reader, if only because these are concepts that haven’t been explored in the public consciousness before. These are considerations that are familiar to those creating within the industry, and regularly glossed over by those enjoying the fruits of their labor.

Matt’s bridging of this disconnect feels long overdue, and the fact that it’s handled in such an appealing, gorgeously visual tome is, frankly, more than we deserve. It’s the sort of book that’s impossible to read without being at least mildly envious of the author for identifying such a massive gap and paving over it so perfectly.

I’ll remind you again that Matt’s my friend. He’s a great guy. And I’ve interviewed him here before in the early stages of the project. But none of that shapes my opinion of the final product. It doesn’t make me like it so much as it makes me appreciate all of the time and the effort that I know has gone into this. It’s a book that very much succeeds on its own merits, and absolutely lives up to its ambition.

If you have any interest in games, visual arts, interactive arts, or the creative process in general, Game Art is very much worth your time. It’s also a handsome enough volume that it makes for a great gift.

It’s available on Amazon and from No Starch Press directly. The latter offers it as an ebook for an outright psychotic $32, though, so, seriously, pitch in the extra few dollars for the physical version.

Here’s hoping Game Art is able to elevate the levels of appreciation and discourse when it comes to…well, game art. It’s a welcoming, inspirational, and by no means exhaustive way to open the conversation. It’s our job to keep it going.

Wow, this is great to hear. I see so many “Game Art” books at bookstores, and they all (the ones I’ve seen, anyway) boil down to super surface-level comments about high-res screen shots of games whose art is not terribly great to begin with. It’s hard to find truly good books about art in general, and with so few people writing *anything* about games I kind of gave up looking for something like this. I will definitely check this out!

Also, this is an interesting quote:

“If you want to get really creative, you’re up against a wall all the time thanks to the rigidity of the programming. Artists have very complex logic of their own; it’s just that their minds work differently than a programmer’s. I do think that’s perhaps another reason there aren’t as many interesting games from an artistic point of view.”

This is great. There’s been such an influx of games that are artistically incredible (typically indie games, whatever “indie” means anymore), but fall apart as compelling interactive experiences. And then you have games like Metal Gear Solid V (which I’m currently in love with) with has the best stealth gameplay of all time, but is downright drab in the art-direction department. It’s very rare to have a game like World of Goo, that combines a very distinct artistic style/aesthetic with simple, brilliant gameplay mechanics.

If this book was written for any one human being, Jacob, I’m positive it’s you.