Almost a year ago I did one of these posts, identifying the references in Conan O’Brien’s brief (but beautiful) Star Wars by Wes Anderson sketch. And now, since I’ll only ever write things about Breaking Bad again, I thought I’d do the same thing for this long, not-quite-as-good (but-still-pretty-darned-good) parody of Jimmy Fallon’s.

As before, watch the above first, because I’m going to make it my business to take all the surprise out of this, write about the jokes until they’re not funny anymore, and basically turn an act of comedy into a text that must be studied until you hate it. Also, as before, I’m sure I missed things…so point them out in the comments below and I’ll add them to the list, give you a credit, and send you a Noiseless Chatter gift basket for playing.

Are you ready? Here we go…

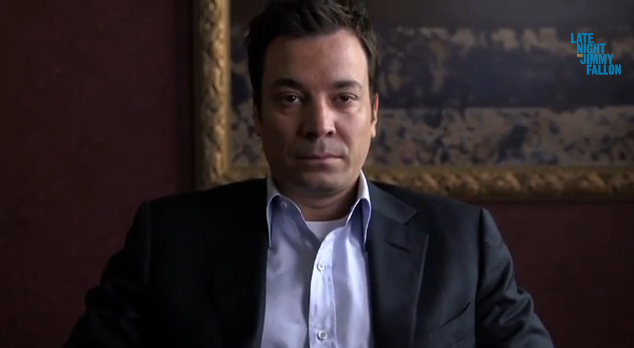

The sketch opens with a nice parody of a scene in the pilot episode of Breaking Bad. (It’s called “Pilot” officially, but the DVDs list it as “Breaking Bad.”) Jimmy, just as Walter White before him, sits numb to the bad news he’s being given. For Walter it was the diagnosis of advanced lung cancer…for Jimmy it’s that he’ll no longer be hosting Late Night. The swell of the sound in Jimmy’s head here is perfect.

I actually do want to point out that I kind of don’t like Jimmy Fallon…except when he’s doing things like this. He was terrible on Saturday Night Live and he’s horribly awkward when interacting with guests…but for whatever reason, Late Night With Jimmy Fallon has managed way more great pre-filmed material than I ever would have thought it capable of producing.

ADDITIONAL: Ace commenter Jory Griffis has better eyes than me, and noticed a mustard stain on the man delivering the bad news. Great detail, and great spot Jory!

I’m only going to be talking about specific references here, not general nods, which is why I won’t say things like “Jimmy Fallon with a bald cap and glasses and a little beard looks like Walter White.” But, if you must know, Jimmy Fallon with a bald cap and glasses and a little beard looks like Walter White.

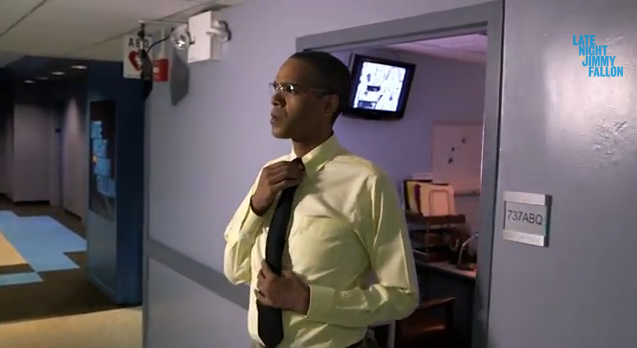

The above shot, though, is obviously based on a very iconic shot from the pilot episode, in which Walter, in underpants and a dress shirt, stands waiting for the police to arrive with a gun in his hand. It’s pulling double duty here, though, as that shot is almost as immediately familiar as the show’s logo thanks to its regular usage on DVD packaging and promotional materials.

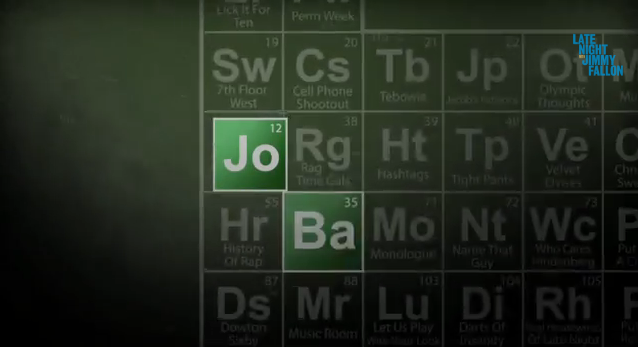

…and speaking of the show’s logo, here’s the requisite reconstruction. The rest of the periodic table seems to be filled with other features of Fallon’s show. I haven’t seen enough of his stuff to know for sure, but I know “Hashtags” fits that context, and obviously “Monologue” does as well. If any huge Fallon fans want to explain them in the comments, be my guest. But then you also have to leave.

Walt walking down the street with his jacket open like this looks very familiar to me. I get the feeling it’s happened a lot of times, often with a cell phone pressed to his ear, but just in case it’s something anyone else can pinpoint…have at it.

Fallon meets his “Jesse.” I can’t quite make out what he calls him. “Haymarks” maybe? I have no idea who that is, but I’ve read that it’s Steve Higgins, Fallon’s announcer. The scene doesn’t play out much at all like it does in “Pilot,” but the plot point is absolutely the same: Jimmy has the knowledge behind making jokes, Steve has the connections to sell them. They team up, and Jesse never dies on Breaking Bad PLEASE DON’T LET JESSE DIE ON BREAKING BAD

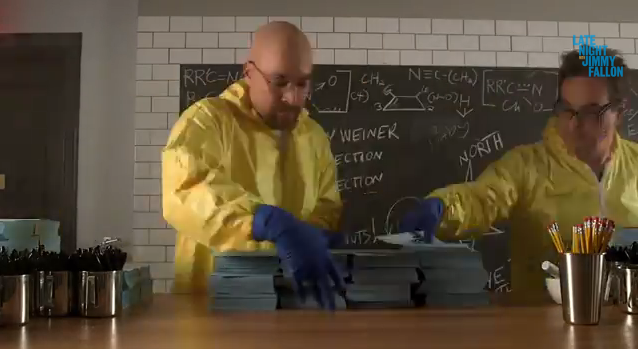

This montage (unlike a later one) contains a soundalike I can’t quite identify. For that reason I’m not sure if it’s a reference to any specific “cooking” sequence in the show, though Steve spinning around in his chair is absolutely Jesse from “Pilot.” There’s also a scene of Jesse fooling around with a chair in “I See You,” but that’s a lot less likely to be referenced here.

The jokes are, of course, written on blue cards with the name of Fallon’s show written on them, which would make them conveniently easy to trace should anyone wish to investigate the illicit activities on display here…

ADDITIONAL: Commenter Ryan identifies the song in the montage as a soundalike for “Dead Fingers Talking,” from Walt and Jesse’s first cook in “Pilot.” Nice ears and ass, Ryan!

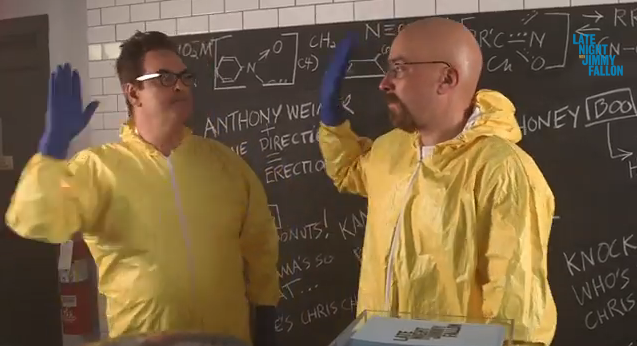

A janitor enters the room to let them know they need to fumigate, but the writing continues…mirroring Walter’s new scheme as of “Hazard Pay.” It’s also an excuse to get them into the yellow hazmat suits, which I’m fine with.

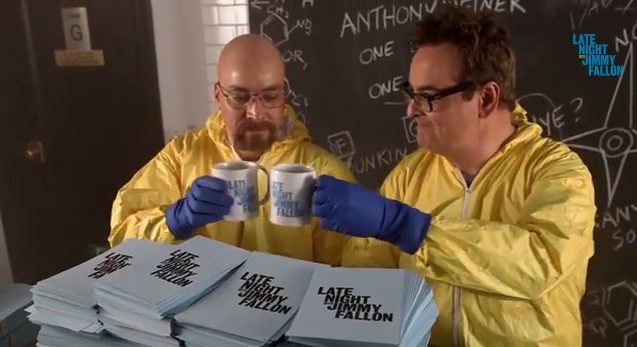

A soundalike of “Crystal Blue Persuasion” plays now, referencing the cooking / distribution montage from “Gliding Over All.”

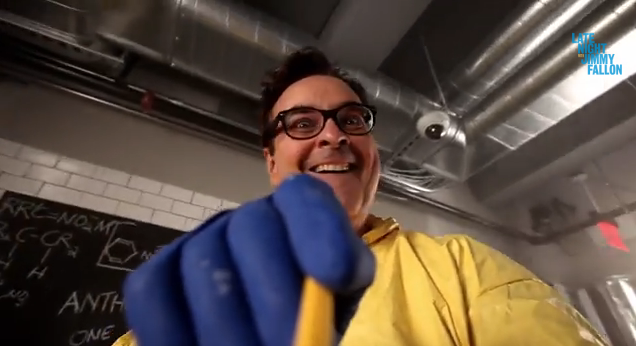

The pencil’s-eye-view is a great little touch…but now I’m hard pressed to remember when such angles were utilized in Breaking Bad. I know there are lots of examples but nothing’s coming to me so HELP.

ADDITIONAL: Jory Griffis to the rescue again, identifying the angle as a reference to one in “Fly,” when Jesse is scrubbing the machinery in the lab.

We’ve seen stacks of blue product on the show many times (especially during the Gus regime) but I think the first time we saw it in the show was “4 Days Out,” where it was also part of a montage.

The two clink their beverages and kick back after a job well done, as in “Hazard Pay.” Now that I’m thinking about it, that was one of the last times Walt and Jesse were truly happy in each other’s company. Knowing this show, I’m shocked that it didn’t last forever!!!

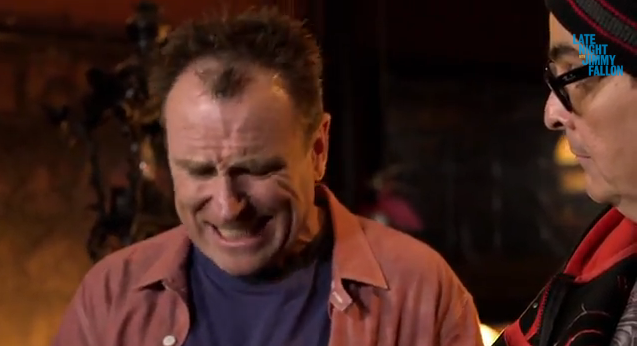

Colin Quinn sampling the blue stuff mirrors Tuco doing the same in “A No-Rough-Stuff-Type Deal,” and they both, if I’m interpreting their comments correctly, believe the product to be “tight.”

Like Hank in “Gliding Over All,” A.D. Miles has an epiphany on the toilet while watching Colin Quinn’s set. Yes, I know the way I wrote that sentence makes it also sound like Hank’s epiphany occurred during a Colin Quinn set, but that’s hilarious to me so I’m leaving it.

I’m not sure what Miles does on Fallon’s show; I’ve seen him in other things, but this sketch makes it seem like he’s a writer for the show or something. Is he? Or did they just bring him in because he can channel Dean Norris pretty incredibly for a guy who looks nothing like him? (And if that’s the case…I’m happy.)

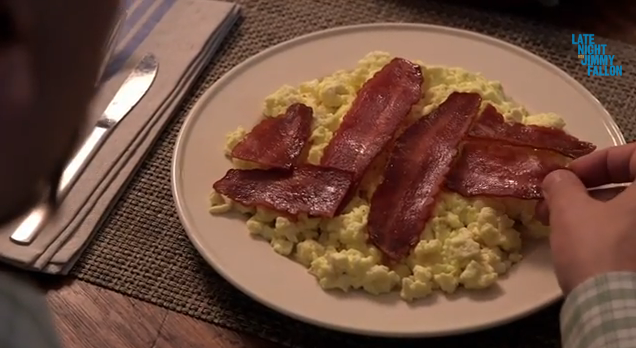

On Breaking Bad we’ve seen Skyler write out Walter’s age in bacon twice, on his birthday. But here Fallon is writing something out himself…as Walter did in “Live Free or Die.” Which has led to some speculation that Skyler is dead by that point. I guess we’ll never know. :(

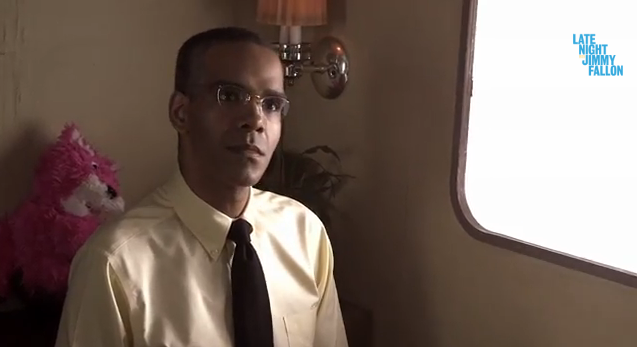

Miles asks Jimmy about the initials…just as Hank does Walt in “Bullet Points.” The wardrobe department deserves some recognition for matching the shirts that the investigator wears as well…that’s a great, unnecessary detail.

The “ya got me” moment from that episode is recreated, with a pretty great punchline tacked on. And I really can’t say enough about how great Miles’ “impression” of Norris is. The speech pattern is spot on.

The first of a few great cameos. Saul reprises his advice to sell in bulk from “Mandala,” as well as his “I know a guy who knows a guy…” bit, and I can’t tell if it’s genuinely good writing or just an expectedly stellar Odenkirk reading, but this ends up being the biggest laugh of the sketch for me.

Also interesting is that this was shot on the actual set for Saul’s office. (Prove me wrong, internet!) Since the show’s finished shooting the set is probably destroyed, meaning they must have shot Odenkirk’s scene a while back. Or maybe it still exists for the Better Call Saul spinoff. Who knows.

Either way, this shows obvious buy-in from the Breaking Bad folks themselves, which is lovely.

Jimmy heads into the Roots’ vehicle (yes…the R.V.) which is billowing with smoke…just as Walt and Jesse’s R.V. was during cooks. Jimmy then meets Gus, who is exactly what you might expect so I won’t talk about that…

…but I will mention the pink teddy bear behind him. It’s the same teddy bear we saw in the black and white intro sequences to “Seven Thirty-Seven,” “Down,” “Over” and “ABQ.” And I’ve only just recently realized that those episode titles can be read together to explain what happened. Gilligan, you sly shit.

Oddly the teddy bear appears later behind Gus as well, in a different place, so either the Fallon crew just stuck it in the background again to make sure we saw it, or they’ve drawn some kind of connection between it and Gus Fring…which seems incorrect unless I’ve misread something.

The bucket of chicken reads Los Pollos Humanos…the chicken humans? I might be missing something. And the chickens in the picture are people in costumes, holding musical instruments. But they’re white guys so they’re not The Roots. Why am I thinking about this chicken bucket.

ADDITIONAL: Commenter Shawambam not only stole the name I was going to give my first-born son, he pointed me toward a youtube clip of the “chicken band” we see here. Evidently Fallon has these guys in chicken outfits come out and perform songs in the style of guys in chicken outfits. So NOW WE ALL KNOW.

Bryan Cranston and Aaron Paul are both in Jimmy’s very disappointed audience. I know this isn’t a direct reference and is just a cameo, but I’m interested by the fact that they aren’t sitting together…presumably because their lines were shot at different times.

I also want to say that Aaron Paul is the only man alive who can pull off a “Boo, bitch.”

An irate Cranston throws a pizza at Fallon so perfectly that it’s the second biggest laugh of the entire sketch to me. This is of course a reference to Walter angrily hurling a pizza in “Caballo Sin Nombre.”

And do pizza places actually sell unsliced pizza?

I kind of want one. I’d sit on the couch holding a massive unsliced pizza, just eating it and weeping.

You can’t tell from a screen shot (so I bet you’re glad I took a screen shot) but the time-lapse sequence here mirrors similar scene transitions on the show.

This was a shitty part of the article. Ignore it.

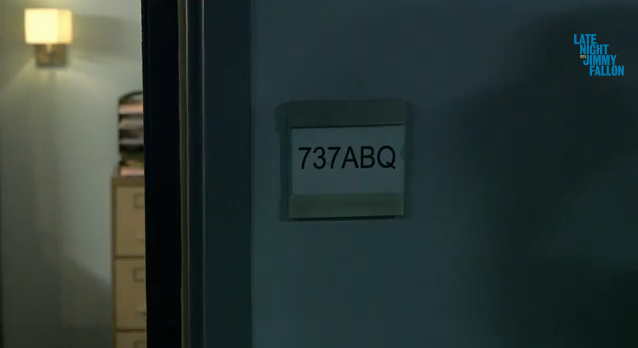

Gus’ office is 737ABQ, referencing the episodes “Seven Thirty-Seven” and “ABQ,” as well as Albuquerque in general, which is where Breaking Bad is both shot and set.

Jimmy and Gus engage in a vaudeville version of Walt’s “I am the one who knocks” speech from “Cornered,” and there is a note on the board that reads “Better Call Saul,” which is the title of another Breaking Bad episode, as well as Saul Goodman’s slogan.

What else is on the whiteboard? I’m glad you asked…there’s a drawing of a fly. This is a reference to another episode title, “A Drawing of a Fly.”

I have a feeling that the shot of Jimmy walking toward the office with his back to the camera is a reference to a specific scene in the show, but I can’t place it. So do that for me.

ADDITIONAL: The walk is framed identically to one toward the start of “Full Measure,” with the camera following Walt from the same angle as he approaches Gus, Mike and Victor after running over the drug dealers. I figured that out. I did that. I did that without any of you!

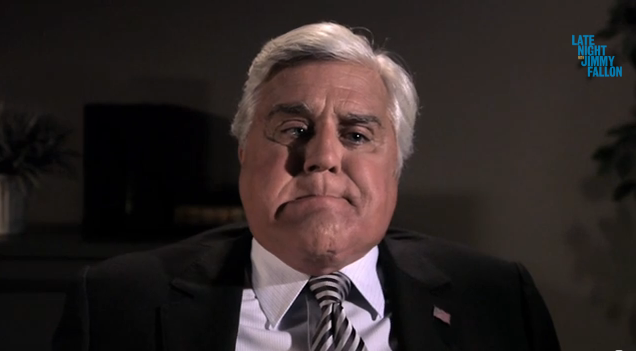

Gus reads a joke so funny he’ll laugh his ass off, and we cut to the hallway and hear an explosion. As in “Face Off,” Gus steps through the door, adjusts his tie, and the camera circles around to reveal…

…that he’s fine. His face is okay. His ass, however, as he walks away, is indeed missing. And while I wouldn’t say it’s brilliant or anything, I do really like the way they dropped hints to this happening throughout the sketch. It feels like they at least tried to capture the layered narrative approach of Breaking Bad, even for this dumb little comedy whatsit about an exploding butt.

Miles interrogates a Hector Salamanca-like figure, in what is a reference to a similar interrogation of the invalid in either “Bit By a Dead Bee” or “Face Off.” Behind Miles is a Lilly of the Valley, and since somebody stole some pot from me this morning I am now positive that Walter White used that type of plant to poison a kid.

The sketch ends with a reveal of our Hector surrogate, which doubles as the only funny thing Jay Leno’s done in approximately 45 years.

So! What did I miss?