FTC Disclosure: I received a copy of this book in exchange for review. No money changed hands and all opinions presented here are my own.

FTC Disclosure: I received a copy of this book in exchange for review. No money changed hands and all opinions presented here are my own.

When I was a boy, I used to go camping with my father. During one of these trips, my brother and I decided to take a little walk together. We didn’t think we walked very far, but trying to find our way back to the campsite was difficult. Everything looked the same and the return trip took at least five times as long as the journey out. Ultimately, though, we found our way back.

That which you have just read is true. But it is not, I absolutely hasten to add, a story. It might be an anecdote, but I doubt it’d be a very entertaining one. More likely it’s the sort of thing I might bring up with a group of friends, all of whom are exchanging brief, inconsequential narratives on the same theme (being lost, childhood memories, camping with kids…). But even in the right context, it doesn’t become a story. It’s just something that in some (but certainly not all) cases might be worth repeating.

I could drag it out, certainly. I could add reams of accurate detail that may well make the recitation more vivid for my listeners, but the compounding of unnecessary detail doesn’t turn it into a story either, and without a great deal of fictionalization, it never could be one.

There’s nothing wrong with fictionalization. At least, not within the context of fiction. (That’s kind of where the word comes from.) Fictionalization is a good thing for stories. In fact, I’d go so far as to say it’s the single most important thing. Storytelling is an art, and art lives and dies by the talent of the artist. We might be fine listening to a close friend tell us about a personal experience, and in that case we might feel cheated if we later found out he was embellishing it excessively.

However when we pick up a novel, we don’t want to read a dry recitation of something that the author did. First of all, that’s not what a novel is. And secondly, the novelist needs to demonstrate, in some way, a mastery of his art. This can take many forms, of course; it can be the active and deliberate bafflement of Joyce or the intense simplicity of Hemingway. It can — even better — be one of numberless possibilities in between those two extremes.

But an artist has to do something, otherwise he isn’t creating art. He’s just saying things.

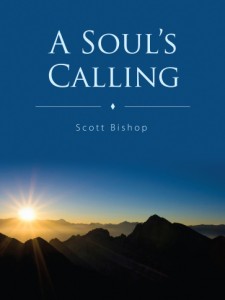

A Soul’s Calling, a novel based on author Scott Bishop’s experience of hiking to the base camp at Everest, just says things.

It’s admittedly difficult to issue this as a universal criticism, especially since the writing in A Soul’s Calling isn’t uniformly bad, but this is essentially a long, long first-draft that is in dire need of a more compelling rewrite. As it stands it reads no better than my camping anecdote, but takes around 1,700 times as long to finish saying nothing. And that’s the problem. Some of my favorite pieces of writing “say nothing,” but they say it in so moving, amusing, or thrilling a way that the act of saying nothing becomes a kind of art unto itself. It takes — or, rather, is sculpted into — a shape, a series of shapes, patterns within patterns that compose themselves into larger movements and statements. That’s what fiction is for.

A Soul’s Calling doesn’t do that. It presents copious details in the hopes that obsessive accuracy will eventually conjure up its own kind of interest in the reader. But it does not.

To be honest, I’m not even sure I should be judging this book as a novel. Its back cover refers to it as a novel, yes, but it also refers it as a memoir…and those two things are mutually exclusive. You can’t actually be both. You can be a Nabokov-esque memoir of a fictional character, or you can be a Vonnegut-like fictionalized memoir, but in each case you’re still writing a novel, and the format (or intention) of memoir becomes a utility…a filter through which that novel is read.

That is not what we have here, and though I’m making a bit of an executive decision by calling it a novel, I think the presence of spirits and talking mountains and a main character who receives visions of an apocalyptic future that he alone can avoid somehow by making this journey all seat the book firmly in the category of “fiction.”

If any of that seems to be out of place for a story about a journey to Everest, then you might be disappointed to learn that it’s also completely unnecessary, and — to be honest — nonsensically handled. When Kurt Vonnegut takes us away from the real-life horrors of World War II to make comical digressions to an extra-terrestrial zoo, or Thomas Pynchon sees it fit to insert a sentient mechanical duck into the surveying party of Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, they do so in order to make colorful points about the things we think we’re familiar with…in order to slant our perspectives enough that we can view the familiar in a new and unexpected way.

However when Bishop employs these strange intrusions, they serve only to confuse his intentions. What’s more, they ring loudly as artificial and empty gestures. After all, when George Mallory was asked why he intended to climb Mount Everest, he famously (and maybe apocryphally) replied with three words that have been connected with the mountain ever since: “Because it’s there.”

Everest is, within our cultural landscape, a mountain whose conquering legendarily requires no justification. It is in itself a justification. If reaching its peak is understood universally as being entirely free from — and separate from — mere human reasoning, then I’m not sure why we need urgent entreaties from the Spirit Realm to justify the comparatively minor trek to its base camp.

The real problem, though, is that this unnecessary justification fails to even justify itself. There’s nothing inherently wrong with making the protagonist the “Chosen One” who alone can prevent massive calamity on a universal scale; this has been the backbone of everything from The Bible to The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. There are countless places you can go with the idea, which is what keeps it from feeling stale in the right hands. It may come across as somewhat trite, but it’s an acceptable triteness that we expect will pay off in some interesting flourishes along the way.

In A Soul’s Calling, however, the protagonist / narrator (who shares a name with the author) some emissaries from the spirit world turn up, tell “Scott” that he needs to journey to the base camp at Everest, and then essentially disappear from the novel entirely. We do hear from them again, but they never actually explain what the issue is, what exact function “Scott’s” journey will serve, or why “Scott” was chosen at all. In fact, every time the narrator describes these conversations or visions, he lapses into an evasive textual shrug, admitting that he can’t really explain what he saw or heard…so, I guess, we just have to trust him when he says that his ethereal Princess Leia assured him he was our only hope. Whether or not he was qualified to shoulder the burden of universal salvation I can’t say, but as a reader I’m absolutely positive he’s not qualified to narrate if he can’t tell us about the most interesting things in the book.

Part of me wants to see this as a deliberate evasion. It wants me to read these moments — and there are many of them — as evidence of unreliable narration. That would indeed go a long way toward turning A Soul’s Calling into a work of art, as opposed to a collection of pages. But that part of me easily loses the war against another part of me: the one that read the book. Bishop’s inexplicable and unexplained forays into a spiritual justification for the trip are simply a baffling obstacle lost in the midst of so many other baffling obstacles, and it becomes an unintentional running joke that the narrator preemptively defends himself against the logical faculties of his audience, assuring us openly that these spiritual visitations — which occur when he’s in bed with his eyes closed — are not dreams. Why are they not dreams? Because they’re not dreams. That’s why. Well, that’s me told I guess.

Even if I could accept that “Scott” were the only hope for both this world and the spiritual world, and that his trip to and back from the base camp at Everest would somehow avoid The Biggest Apocalypse Ever, I absolutely cannot accept that, as a writer, Bishop so eagerly buries the lede.

If you were personally visited by spirits who told you that you needed to perform some earthly task in order to prevent the Alleged Cosmic Implosion of All That Ever Was and Will Be, and you did that thing, you’d then be pretty eager to tell everyone about it. Right? I know I would. But I also know that I’d spend a lot of my time talking about the spirits and the apocalypse, and probably wouldn’t spend nearly all of 340 pages methodically documenting that earthly task instead. And I suspect your narration would have a similar bent. “Scott,” on the other hand, waives away interest in the spirits, and thinks we’re more interested in how many times he stops for Pringles along the way to base camp.

The story here is that “Scott” was visited by ambassadors from another realm — a realm most human beings don’t even know exist — and assigned an urgent task that alone can avoid total intergalactic destruction…but Bishop thinks the story is that he took a difficult walk through the Himalayas. And I simply cannot abide that oversight. After all, that’s what prevents this from being a story, and restricts it to being instead a sloppily-framed and long-winded anecdote.

There are lots of other issues at play here, as well, including a massively problematic relationship at the book’s core. “Scott” and his guide Tej feud constantly on their way to Everest. To his credit, the narrator understands that this relationship is strained. To his much larger debit, he never realizes that the reason it’s strained is that he keeps arguing with Tej, childishly overriding his experienced council, and insisting that they do things “Scott’s” way. After all, Tej has only spent a lifetime physically guiding people along this exact route…and “Scott” has done several nights’ worth of reading on the Internet, so clearly he should be stubbornly disregarding everything his guide is so emphatically trying to tell him.

I was absolutely astounded by the way this played out between the narrator and Tej. All along I was expecting “Scott” to learn his lesson, but no, A Soul’s Calling wants us to believe that the moody American was right all along, and Tej was out of line for questioning him.

I’ve never seen anything like this. I kept expecting “Scott” to receive his comeuppance in some way and realize that the rich and beautiful world he’s so desperately trying to make conform to his expectations is actually the world he should be opening himself to. I find it hard to imagine a version of The Darjeeling Limited in which the Whitman brothers learn that it was smart of them to cling to their possessions and petty grievances, and I find it impossible to imagine that that would work at all as a film. When you fight against accepting another’s culture, the audiences laugh at you because they know better. When you stop resisting, the audience is on your side because you learned your lesson. In A Soul’s Calling however the opposite happens, and the audience is meant to be glad that “Scott” had the willpower to resist the foolish guidance of his (ahem…) guide. And I’ve never seen anything like that before. It genuinely hurt to read.

There’s more I could talk about at this point — such as the narrator’s explanation that every person who’s ever disliked him in life was actually being manipulated by evil spirits (which must be pretty nice, as everyone who’s ever disliked me in my life has done so because I was a dick to them in some way…you know, something that I’m actually responsible for as a human being and therefore must learn a lesson from) — but I think I’ve said enough.

A Soul’s Calling could have had some value, at least potentially, as a dry yet meticulous travelogue, but it ultimately fails there as well because the travel comes across as dead and routine. The narrator arrives somewhere, Tej tells him to go one way, the narrator throws a tantrum and goes another, the narrator gets exhausted, the narrator leans on a rock, the narrator tells us about something he read on the internet, and the narrator goes to sleep in a lodge. It’s just a simple, cyclical repetition of the same few ideas, with no substance or character at all, making this magical and important journey feel more like a boring car ride during which nobody feels like looking out the windows.

I’d like to read a version of A Soul’s Calling that makes something of its own components. I want to know what the spirits are talking about, exactly, rather than getting a spill of vague gibberish about them every one hundred pages or so. I want to see the narrator grapple with the possibility that the spirits aren’t real, and that he might actually be losing his grip on reality, just as any human being would. And most importantly, I want to see the narrator face some consequences for his behavior toward other people, without simply being able to handwave their disgust as being due to the interference of some invisible boogey man.

Because what we have isn’t a story. It’s a recitation of things that happen, yes, but it’s not a story. And it’s not a novel, and it’s not a memoir, and it’s not a travelogue. It’s a numbered collection of pages, and it’s waiting for somebody to give it shape. I hope somebody does; it’ll undoubtedly be for the better.

FTC Disclosure: I received a copy of this book in exchange for review. No money changed hands and all opinions presented here are my own.