For the sake of vengeance I did struggle to regain it.”

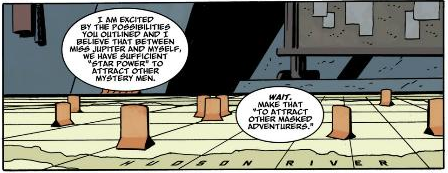

–The Crimson Corsair: Minutemen #1

Join Jacob Crites as he reads too deeply into every issue of Before Watchmen: Minutemen. The following is part one of a six part series.

There are people who will never like Before Watchmen simply because it exists. If you’ve ever read Watchmen, you know that this viewpoint is not entirely unreasonable. There was no more story to be told by the end of Alan Moore’s masterwork; he, along with artist David Gibbons, had challenged and redefined an entire art form with their unparalleled mastery of the comic medium. And it also, even stripped of its technical brilliance, is still a really incredible story with characters that leave a lasting imprint somewhere in the deep pit of your being.

But you know all this already. You know why it shouldn’t be done. And you know why DC did it anyway. What none of us knew is just how incredibly well such a seemingly horrific idea could turn out.

Things immediately feel different than the original Watchmen, both in tone and in style, and this is important. For one, consider the contrast in entry points: we were introduced to Watchmen‘s world through Rorschach, an enigmatic, mentally unstable masked vigilante who was unmistakably and tragically the result of the dark, corrupted world around him. In Minutemen, the story is told through the eyes of Hollis Mason, by all accounts the most good-hearted man we know of in the Watchmen universe, and one of the world’s original masked vigilantes: Night Owl. We know Hollis a little from reading excerpts from his tell-all book, Under the Hood, in the original Watchmen series, but here we see his unabashedly old-school idealism and optimism first hand.

But, of course, it’s not that simple. With Watchmen it never is. Through flashbacks, he looks back on his crime-fighting years with nostalgia, and he regrets that he can’t take the rose-tinted glasses off. For despite the good he sees in what the Minutemen did, who the Minutemen were, he understands with overwhelming clarity that the actions that he and his fellow masked “heroes” had made had helped shape a corrupt and twisted present with a future almost certainly doomed to implosion.

“Over the months it took me to complete [Under the Hood], I found the act of writing seemed to purge me of the darker aspects of my secret life,” he says, “as if I trapped all of it in a bottle I could now toss into the surf. Lately, when I think of those times, the dark parts fall farther and farther away from my limited line of sight. From down here on earth, I can only see what I want to see. From here in my empty apartment I can only see the good.

“Over the months it took me to complete [Under the Hood], I found the act of writing seemed to purge me of the darker aspects of my secret life,” he says, “as if I trapped all of it in a bottle I could now toss into the surf. Lately, when I think of those times, the dark parts fall farther and farther away from my limited line of sight. From down here on earth, I can only see what I want to see. From here in my empty apartment I can only see the good.

But he doesn’t mean it. Not entirely. Least of all when referring to himself. He speaks of his former comrades Byron (Moth Man) and Ursula (The Silhouette) with love and admiration, even after the tabloids had trampled their reputations and left them to die; but he speaks of himself with a level of skepticism and unease he reserves for no one else but The Comedian. For Mason is unconvinced that his own heroics should be labeled as such. In a way, despite his nostalgia, he speaks of his years as Nite Owl with a tinge of regret:

“I knew I wanted to do good, and I’m pretty sure that, on a community level, that’s just what I did. But that didn’t explain what I was doing. There are all kinds of sane ways to help your community that don’t involve a mask and short pants. When it came right down to it, I did it for the thrills. For the excitement of putting myself on the line.”

And so through this conflicted character Minutemen becomes a fascinating book: one in which we watch a good man become a part of a thing we know he has no chance of stopping from inevitably spiraling out of control; and in which we see that same man, now, wondering whether or not it would have been worth stopping anyway.

If you didn’t already consider Darwyn Cooke to be one of the most talented artists in modern comics, start paying attention. The man, in addition to his expressive and beautiful artwork, effortlessly deepens and humanizes these characters within mere pages of a single issue. Throughout the piece he has the unenviable task of introducing no less than eight masked vigilantes, and still manages to imbue them each with a level of depth unseen in most series.

Yet although containing the unmistakable undercurrent of tragedy that Watchmen is known for, as mentioned earlier, there is a palpable sense that something is different. Part of what that something is, in addition to our entry into the comic’s world, is enthusiasm. Color. Joy, however fleeting.

Watchmen has been called, amongst many things, a comic about comics, so it’s appropriate that its prequel should highlight the colorful exuberance and optimism of the Golden Age of Comics. In the costumes, framing of action and dialogue, Cooke captures the bright-eyed innocence of early super hero tales, best of all during a depiction of a pre-picture advertisement about the “superhero” Dollar Bill, a corporate mascot of the National Bank Company.

But Cooke wisely never veers into the territory of pure comic-book silliness. Even at its most colorful, thanks to Hollis, the Minutemen are always viewed with the not-so-slight air of cynicism. Dollar Bill, despite his colorful costume, is a corporate sham. The Silk Spectre, with the help of her acting agent, fakes elaborate crimes for her to “fight” for the sake of publicity.

But for a minute in time, it didn’t matter. They had fun, were adored, had toy lines, starred in movies. They had a sort of vigor and cheeriness about their crime-fighting that their eventual replacements, the Watchmen, never had a shot at attaining. Maybe that’s what feels different: in the world of Watchmen, it was already too late; the world was a dark place through and through and there was no turning back. Minutemen takes place during a blip in time where masked vigilantes could fight crime, be celebrities and inspire their country without fearing the consequences.

It wouldn’t last long.