Fiction into Film is a series devoted to page-to-screen adaptations. The process of translating prose to the visual medium is a tricky and only intermittently successful one, but even the fumbles provide a great platform for understanding stories, and why they affect us the way they do.

I grew up reading Stephen King. Many of you surely did as well. I’d blitz through an entire novel in a weekend, or a night. Hundreds of pages flying by like a few dozen. I liked them without loving them. Many of you surely did as well.

I grew up reading Stephen King. Many of you surely did as well. I’d blitz through an entire novel in a weekend, or a night. Hundreds of pages flying by like a few dozen. I liked them without loving them. Many of you surely did as well.

King is a fascinating writer, if not an especially good one. He’s arguably the ultimate publishing success story. He’s prolific, he’s rich, he has studios scrambling for the rights to his work before he’s even started writing it. Other writers either admire him or are jealous of him. I’m not sure there’s anything in between.

He fascinates me for two related reasons. Firstly, he’s an unstoppable fount of incredible, fertile, resonant ideas. A rabid dog attacks people trapped in their car. An alcoholic in the throes of cabin fever becomes a danger to his family. A mentally unsound fan holds her favorite author captive. These are writing prompts that could spawn thousands of works of fiction, and any one of them could be great. King turned each of these and so many more into enduring favorites. That’s amazing.

Secondly, though, he doesn’t seem to know what’s good about his own work.

This is remarkable to me. I find it difficult to accept the fact that somebody could be so successful an artist for so long and not understand his own strengths and weaknesses, but here we are. And so great moments are buried within meandering, tedious, clumsy passages. Fantastic characters jostle for space with unnecessary, functionless ones. Surprising flashes of human insight are diluted by clunky dialogue (often written in poorly considered dialect) that even when he was young seemed to have been written by an old man with an understanding of young people that was at least 20 years out of date.

The most visible example of this is his reaction to 1980’s The Shining. King was unquestionably blessed to have his not-all-that-great novel turned into what is arguably the finest horror film ever made. By Stanley Kubrick, one of the finest director’s we’ve ever had. Starring Jack Nicholson, one of the finest actors who’s ever lived.

Writers would sell their soul for an adaptation like that…one which improves upon the source material and enhances its legacy. But King felt ill-served by it and believed that it did his novel an injustice. In 1997, 20 years after the publication of The Shining, King got the chance to prove to his fans that Kubrick had gypped them.

He made his own adaptation of the book, a three-part miniseries, a six-hour epic directed by Mick Garris, whose Critters 2 and Psycho IV credentials evidently impressed him in a way that Kubrick’s filmography did not. And King absolutely made sure to set his version of the film apart from Kubrick’s in one key way: it was fucking terrible.

The arresting, immortal, chilling imagery Kubrick brought to The Shining left King cold, apparently, because it didn’t have poorly rendered topiary monsters and a cameo from King himself conducting an orchestra of ghouls. All King ended up proving was that he was the last person who should be given the final word on his own adaptations. He produces good material, but a smart director will trim an awful lot to find it, and rework even more to elevate it.

All of this is to recognize that King’s been largely served by solid adaptations. Not uniformly, no, but they tend to find the germ of King’s idea and present it in a way superior to the original, clumsy text.

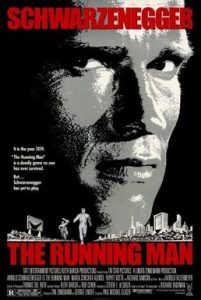

I first read The Running Man in my late teens, and I learned there was already a film version soon after that. I tracked down a copy and rented it, looking forward to what I knew had the potential to be a great film.

It wasn’t.

Oh my Lord was it not.

King’s The Running Man was published under the name Richard Bachman, his pseudonym for a brief period. During that time King wrote one of his best novels (The Long Walk) and several of his worst.

The Running Man was…okay. It might be the only Bachman book that I’d position between those two extremes. Even as a teenager who shouldn’t have known better, I could tell it wasn’t living up to its own potential. I found it difficult to put down, don’t get me wrong, but it was a potboiler. An effective one, for sure, but also one that relied on moving the reader along quickly so that he or she wouldn’t have enough time to realize the novel wasn’t very good.

Its central concept, though, was great, and a half-decent adaptation could do a lot with it.

A half-decent adaptation was miles away from what we actually got.

Arnold Schwarzenegger stars as King’s hero, Ben Richards, but the connection between the two incarnations of the character doesn’t run much deeper than the name. The novel version is a desperate, unemployed everyman with a dying infant daughter who volunteers to participate in a game that will see him hunted and almost certainly killed, because every hour he survives means more money for his family.

The film version, by contrast, is Arnold Schwarzenegger.

We’ll get into the massive differences in the two versions of the story shortly, but, right now, I will say I understand the temptation — on the part of the director, the studio, the marketing team — to eschew the original plot entirely once they realized they had Schwarzenegger, reshaping it as a mindless, self-contained action spectacle.

At this stage in his career, Schwarzenegger had starred in two Conan movies, Commando, and The Terminator. Predator was released the same year as The Running Man. Schwarzenegger was fast becoming a star, and he was becoming a star for very specific things. To plug him into a movie in which he didn’t get to do those very specific things was to invite commercial failure.

The changes to the source material are severe to the point of almost complete detachment. Instead of a gripping story of a man surviving — barely — by his wiles as a team of skilled hunters pursues him relentlessly, we get Schwarzenegger working his way through an uninspired video game boss rush. The question King posits is something along the lines of, “How far can a man push himself when his family’s future is on the line?” Director Paul Michael Glaser’s question is more like, “Can the guy famous for beating people up beat some people up?”

It’s tempting to say that Schwarzenegger is miscast, and had anything beyond the title survived the process of adaptation that would certainly be the case. But the film version of The Running Man fails to do anything noteworthy with its star anyway. It was reimagined as something else that didn’t work.

Both versions of the story take place in a dystopian vision of the future. The novel puts the year at 2025, and the film rolls it back for no real reason to 2019. At the center of each is a television program called The Running Man, which is the most popular show on the planet.

That’s about where the overlap ends, and even though the Running Man TV show exists in both realities, they’re completely different.

King’s version is just one of many shows produced by the Games Network, a government-sanctioned entertainment outlet that puts voluntary contestants in dangerous situations for potential profit. King alludes to similar TV shows such as Run for Your Guns, Dig Your Grave, Swim the Crocodiles and How Hot Can You Take It, but the biggest payout is earned through The Running Man.

The Running Man is a game show, but isn’t quite presented like one. It takes the form of a nationwide manhunt, with the contestants trying to stay ahead of a group of mercenaries known as the Hunters, led by a man named Evan McCone.

The contestant’s family is given an advance, and the contestant himself gets a 12-hour head start. He can go wherever he likes and do whatever he likes, and every hour he survives nets his family 100 New Bucks (because this is The Future), but the Hunters are always in pursuit and will kill him if they find him. Viewers can play along at home by sending tips to the Network if they see the contestant, earning them some money as well. The contestant earns bonuses for every agent of law enforcement he takes out, and surviving a full 30 days means he wins and goes home with the grand prize of one billion New Bucks.

Two complications arise. First, for the contestant: nobody has ever survived anywhere near 30 days. Ben Richards knows this, though, and hopes only to survive long enough to leave his wife and daughter secure financially.

Second, for the reader: how the hell do you do a show where everyone involved is hidden somewhere? King…doesn’t quite know how to answer that. He outlines a rule requiring the contestant to send the Network two videotaped messages every day, which are then used as part of the episode that night. If the contestant fails to do so, they forfeit their winnings and are still hunted.

It’s difficult to imagine millions of people tuning in each night to see some prerecorded video of a man in a hotel room saying, “Yes, hello, I am still running for my life,” let alone the bloodthirsty, howling studio audience King describes. The episode in which that man is caught and gunned down, yes. But the umpteenth episode in which nothing happens and nobody’s around aside from the host? No.

There is one tantalizingly unanswered question this raises, though. Richards is promised that the Hunters will not be given access to any information obtained from the postmarks on the recordings he mails in, but the ease with which they find him (and everybody) makes it easy to believe this is a lie, and the game is indeed fixed. To King’s credit, he either chose not to resolve this definitively or forgot to. Either way, it’s nice that we don’t know. The Hunters are either just that good at their jobs, or they hang around waiting for the Network to tell them exactly where the contestant is hiding. (Or, at least, the zip code.)

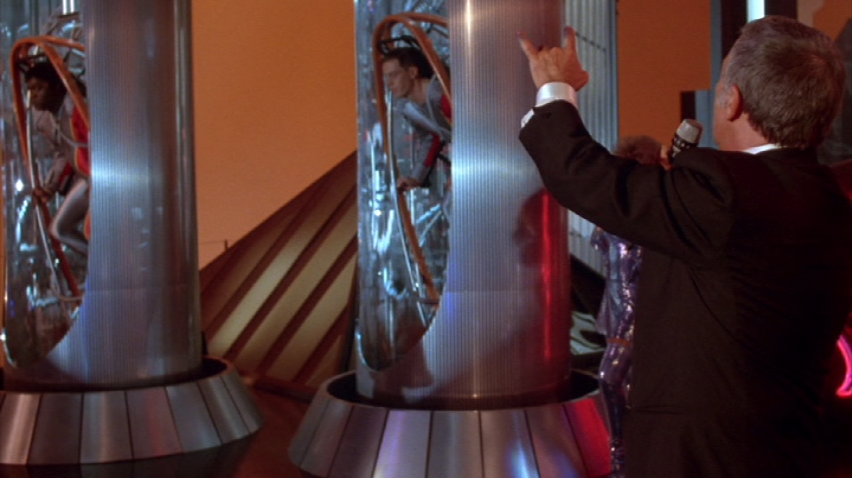

Glaser’s version of The Running Man does at least operate the way we’d expect a game show to operate; that is to say, the audience can actually see what the hell is happening.

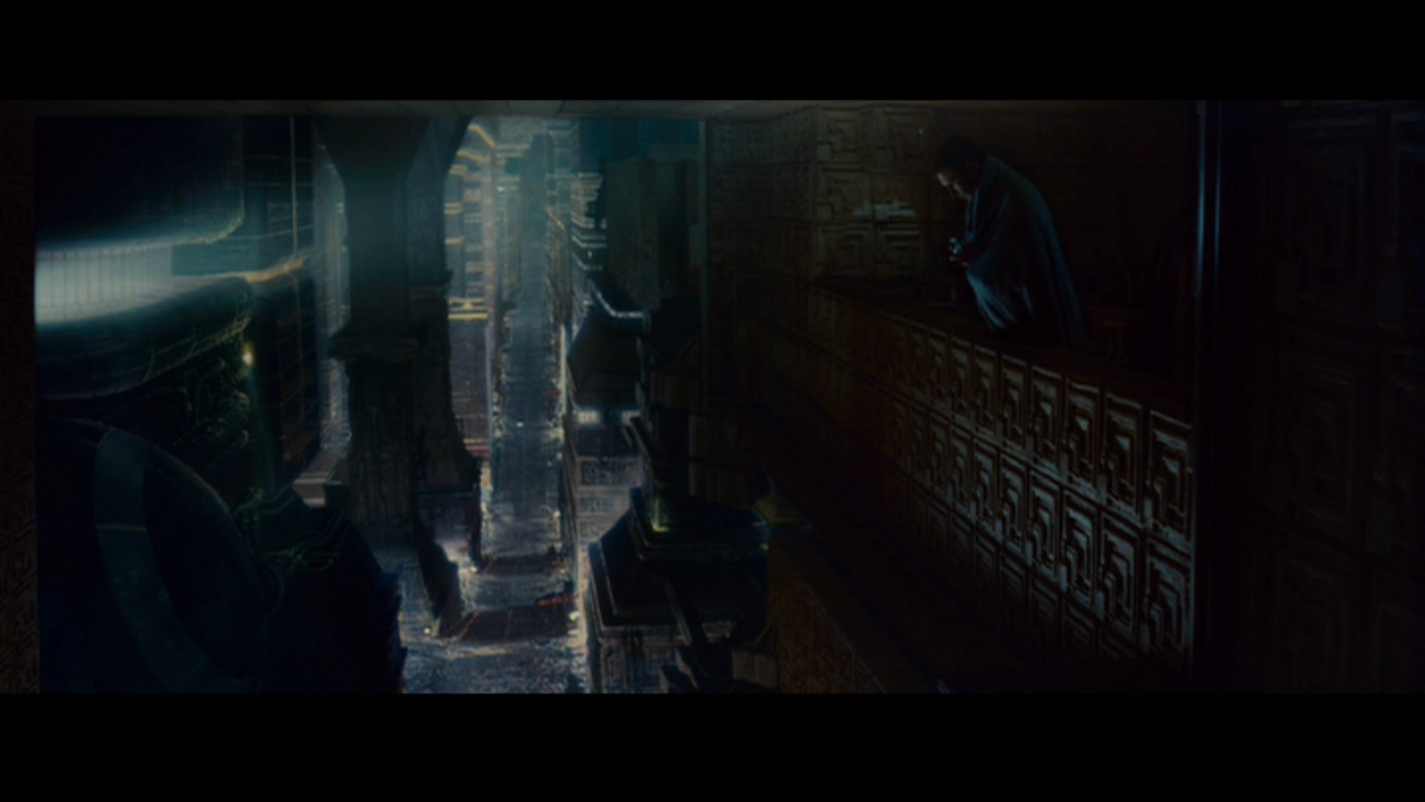

Here, The Running Man is a live broadcast in which convicted criminals (not volunteers) are loaded into shuttles and launched into a Game Zone — a walled-off, disused area of the city — below the studio. It’s still very large (400 square blocks, which seems like an odd unit of measurement when blocks are longer than they are wide but there you go), but it’s still, essentially, an enclosed combat arena.

The audience watches a video feed of the contestants squaring off against the Stalkers, who are gimmicky, themed athletes, something like a cross between WWF wrestlers and American Gladiators. The contestants don’t earn money, but if they survive for three hours they win their freedom.

That obviously works better as a television show than King’s version does, so it clears that rather significant hurdle, but this also leads to its own problems.

For instance, it’s never clear how often the contestants are in view of a camera. If they’re constantly being filmed, the Stalkers wouldn’t have to hunt them out and there would be no game. But for the audience to reliably see the fights unfold, there would have to be nowhere for them to hide from the cameras.

Of course, the answer should be that there is nowhere for them to hide from the cameras, and the “hunting” of the contestants is only dramatic flair. Should be. But there’s an unnecessary subplot about the contestants (four in total) tracking down and jamming “the uplink to the satellite,” essentially preventing the Network from broadcasting. If anyone saw them do that, all pretense about the contestants being able to hide would be dropped immediately and the Stalkers sent to kill them at once. Instead, the contestants are allowed to fiddle with it at their leisure, so I guess they really are able to hide.

Also, forgive me for asking because I know this is totally out of line, but…why, exactly, is the satellite uplink located within the Game Zone? Even if they never expected contestants to be able to hack it or sabotage it, isn’t the mere fact that massive gladiators with chainsaw motorcycles would be engaging in active combat around it a bit worrying? Shouldn’t the uplink be located…I don’t know…literally anywhere else on Earth?

At one point it’s revealed that the resistance group that we meet early in the film have a hideout that’s also within the Game Zone. How do they get in? How have they not been spotted? I guess they could have tunneled in from the outside, but the fact that they’re still alive and Richards and his buddies can meet up with them proves that the Network needs to do a much better job of paying attention to what, exactly, is in their own damned Game Zone.

These things feel like holdovers from a version of the script truer to King’s tale. If Schwarzenegger were indeed fleeing the Stalkers openly across America, he could certainly stumble upon uplinks and resistance camps and anything else Glaser would like him to find. But for him to stumble upon these things in what is essentially the show’s own studio is a profoundly idiotic contrivance.

There’s also the odd fact that the Stalkers seem to have their own dedicated entrances in the Game Zone, reflecting their gimmick and, I suppose, providing a bit of visual drama to their introduction. Which is fine. But since they don’t seem to show up until the contestants are exactly there, it should be pretty easy to survive just by keeping away from the elaborately lit entrances, no?

Also notable is the fact that Schwarzenegger is actually on the run early in the film, but is captured and brought to The Running Man‘s set. In King’s version, Richards starts on a sound stage and runs. In Glaser’s, Richards runs and then comes to a sound stage. One is clearly a less thrilling progression than the other, and it leads to the bizarre realization that in a film called The Running Man, the man was stopped from running so he could hide instead.

While the film was in production, Glaser was brought in to replace the original director, Andrew Davis, who had fallen behind schedule. I know nothing about what creative differences we’d find between the two versions of the film, but I almost get the sense that some of these things were holdovers from an earlier version of the script that actually did more clearly reflect King’s original.

This is seemingly supported by the fact that the version of The Running Man we did get feels like two different films badly stitched together. One of them is a mindless action movie in which Schwarzenegger beats up a guy and then beats up a guy and then beats up a guy and then the credits roll, and the other is a social satire. “Game show in which you fight for your life” is a concept that can certainly go in either direction, but this film wants it to go in both. One isn’t interesting, and the other isn’t given enough space to be interesting.

The social satire just barely surfaces at various points throughout the movie. Early on we catch a glimpse of a television show in which a man climbs a rope while vicious dogs leap up at him, bite at his legs, and eventually pull him down to his presumed grisly death. Words appear on the screen: “Climbing for Dollars will be right back!”

It’s funny. It’s also funny when a man meets with the captured Richards before the show and introduces himself by saying, “I’m your court-appointed theatrical agent.” As is the show’s announcer saying that members of the studio audience receive “procreation pills, both adult and kiddie sizes, and the latest edition of The Running Man home game.”

These are lines and details from a much better version of the movie, one that leans into the ridiculousness of the premise while still making its point. But they’re also rarities, moments of fleeting invention bowled over and smothered by brainless, uninteresting action set pieces designed to say precisely nothing.

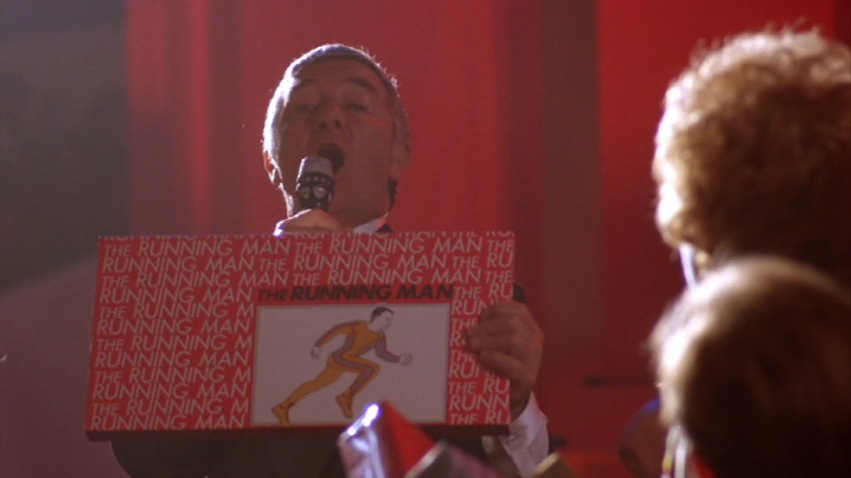

The connective tissue between these two competing versions of The Running Man also, perhaps miraculously, is the film’s lone highlight: Richard Dawson.

Dawson plays Damon Killian, the host of The Running Man, with the oily charm and swagger only a man with decades of experience in the industry could bring to the role. He is eager to have fun with his own image and ends up being the most entertaining thing in the film by a country mile. In short, he knows how to work his audience…both his fictional one and his real one.

Again, I have no way of knowing this for sure, but I have to imagine Dawson brought his own ideas to the character. If that’s not the case, then he was written far, far better than any other character was, and I doubt that very much. More likely there were words on a page, and Dawson, the old pro, embellished them, enhanced them, gave them a life that wasn’t there.

Even as a teenager watching this film for the first time, I could tell Dawson was operating on a level well above the rest of the material. He was believable…an actual character among the caricatures.

I recognized him from Family Feud, of which he was the original host. (He came back to host it again in the 1990s.) Prior to that he served as a regular panelist on The Match Game, which I used to watch in reruns. My friends and I even singled him out as the reliably intelligent one; contestants who did not agree with Dawson’s answers sure seemed to pay the price.

In The Running Man, Dawson embodies his own legend, and the film is infinitely richer for it. He gladhands and compliments and makes people feel important before firing them behind their backs. He’s a cold, evil man who becomes warm and lovable the moment the cameras turn on. He hawks Cadre Cola at the same time he gives the impression he wouldn’t be caught dead drinking that shit. He even brings his habit of kissing old ladies on Family Feud into these darker environs. “The love of my life, my number one fan, Mrs. McArdle!” he says. “I want a kiss now, a big kiss, but remember, no tongues.”

Lives are at stake. Blood will be shed. People will die. And Dawson is all smiles and cheese.

It’s wonderful, and it feels like Dawson knowingly undercutting his own legacy. Since he plays the on-camera version of Killian so much like the game show host he actually once was, he’s inviting the public to question how different he might be when the cameras are off. Was he secretly villainous? I truly doubt it, but the man sure enjoys playing with the possibility.

Dawson fits into the both the social satire version of the film and the action movie that needs an entertaining villain. He’s the one and only aspect of The Running Man that succeeds, and that’s entirely down to Dawson himself.

There’s even a great moment that was nearly a terrible one, redeemed, of course, by Dawson. When Schwarzenegger is about to be sent to the Game Zone, the Austrian superstar says, “I’ll be back,” a nod to his already immortal catchphrase from The Terminator, only three years old at this point.

It’s jarring. We’re watching a crappy movie that has gone out of its way to remind us of a far better one. And though Dawson’s reply was certainly in the script, it’s fitting that he, the movie’s bright spot, was the one to deliver it.

He leans in to Schwarzenegger and says, “Only in a rerun.”

Everything about Dawson here is great, and I’d wager Killian’s signature mannerism — pointing with his fingers in a “devil horns” arrangement — was brought to this film by the actor himself. If I’m wrong and that was actually in the script, it’s the cleverest piece of business the script gave any actor by a landslide.

If The Running Man were a better film, I think Dawson’s performance would be remembered among the all-time great corny villains. Instead, it’s wasted on this, an oddly complicated framework for Schwarzenegger to dispatch some meatheads and spout one-liners.

Damon Killian is a composite character of several in the book. He’s assistant director of games Arthur M. Burns, director Fred Victor, host Bobby Thompson, and obviously Games Network head honcho Dan Killian. Rolling all of these characters into one unified face of the network is a wise decision on the film’s part, especially since, in the book, Dan Killian is the one Richards singles out for abuse and eventual revenge, which seems a bit odd when the others were far more responsible for his ordeal.

It’s less odd — but far more problematic — when you realize that Richards fixates on Killian because of the color of his skin. The other Games Network representatives are white, and Killian is black. Like, black black. So black you just know he’s a bad guy. Here’s how King introduces him:

The man behind the desk was of middle height and very black. So black, in fact, that for a moment Richards was struck with unreality. He might have stepped out of a minstrel show.

Jesus Christ, Stephen.

In the book, Richards endures a number of personality, intelligence, and psychological tests before taking part in The Running Man, and he demonstrates — and we are conclusively told — that he harbors racist sentiments. Dan Killian is certainly not a sympathetic character, but it’s more than a little uncomfortable that his skin color is what turns him into a punching bag.

Richard Dawson is about as black as a daffodil, so, thankfully, his casting sidesteps that entire, unnecessary minefield.

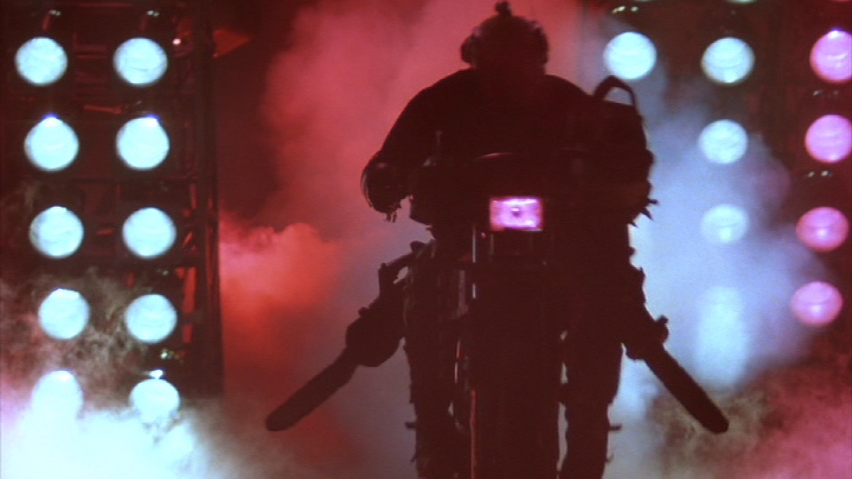

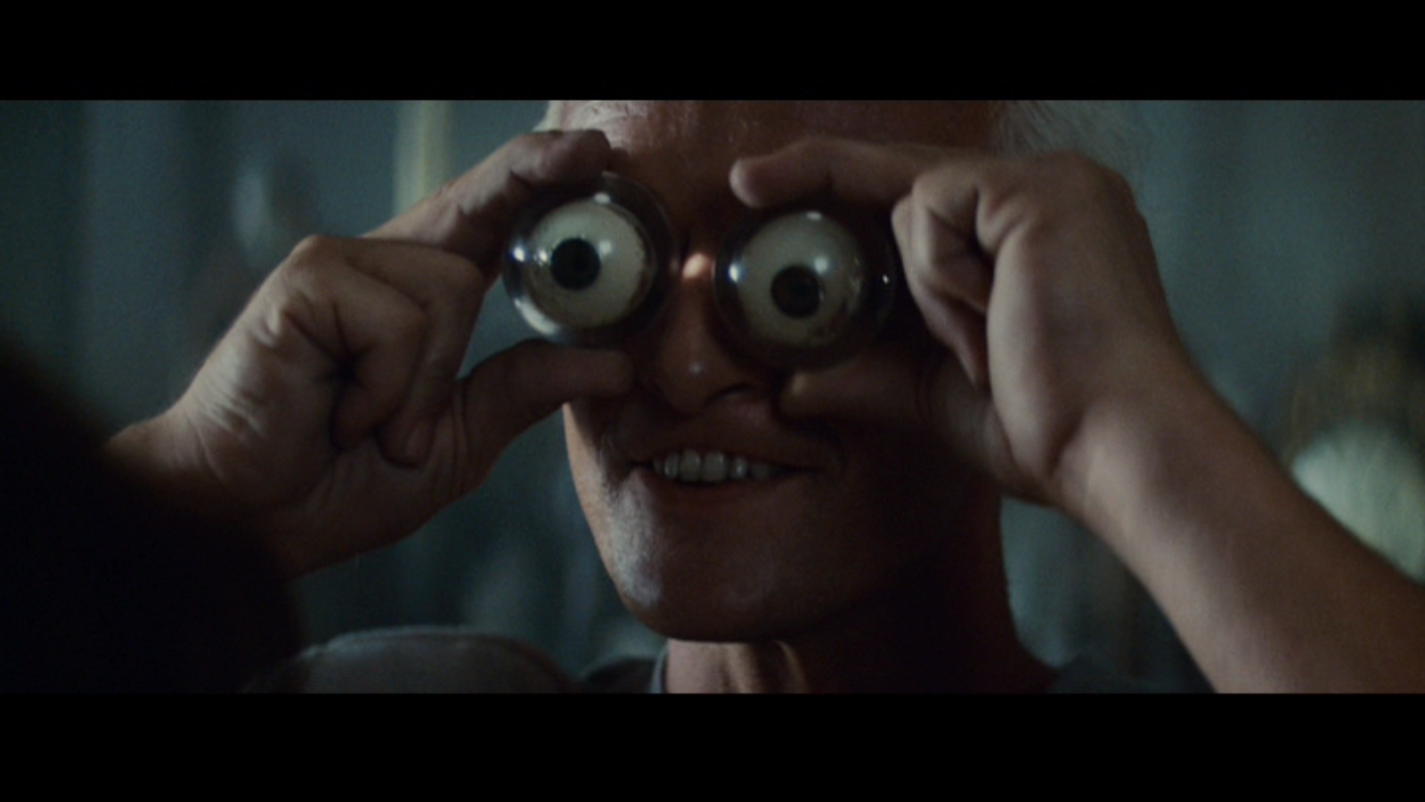

While many characters are condensed into Damon Killian, though, the Hunters are expanded. The only one named — and the only one we really get to meet — in the book is Evan McCone, who organizes and manages the team. In the film, the Stalkers have distinct identities of their own.

Distinct, but not very good.

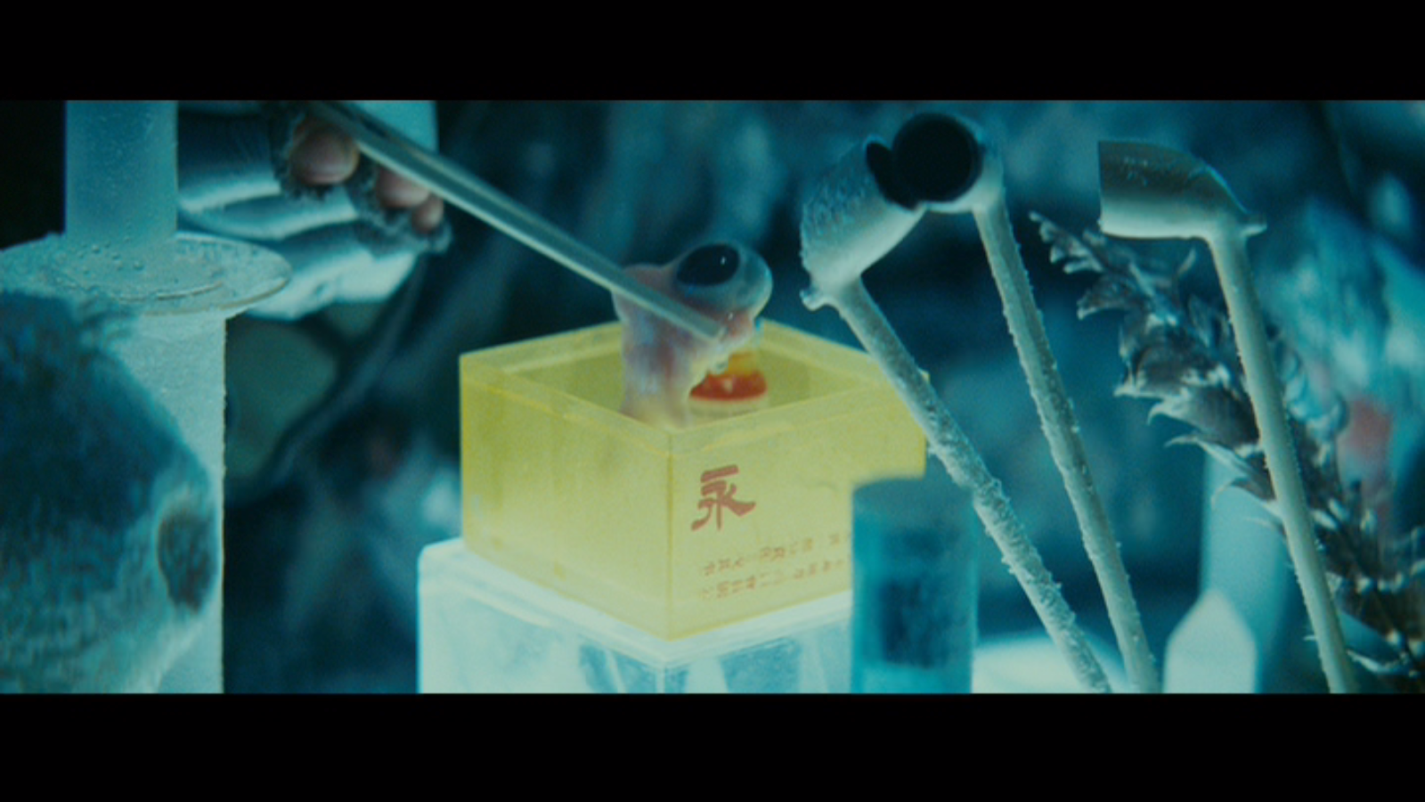

The Stalkers in this movie have gimmicks and nicknames that make them sound like G.I. Joe characters. Fireball. Dynamo. Buzzsaw. Captain Freedom. One of them, Subzero, even had a name that would be used in 1992’s Mortal Kombat, which reveals just how video-game-ready these characters actually are.

In King’s original, the Hunters were unseen presences, shadowy threats without distinct identities, because it was important that Richards couldn’t trust anybody. A hobo. A jogger. A street vendor. A policeman. Anybody could be a Hunter, and anybody could report him to a Hunter.

There’s a great scene of masterful paranoia that unfolds after Richards, under an assumed identity, takes refuge in a YMCA in Boston. With nothing else to do, he stares out the window…and the normal behavior of passersby gradually makes him feel less and less safe.

Richards noted with a numb, distant terror that a good many of the newspaper bums were idling along much more slowly. Their clothes and styles of walking seemed oddly familiar, as if they had been around a great many times before and Richards was just becoming aware of it — in the tentative, uneasy way you recognize the voices of the dead in dreams.

A man waiting for a bus. Two friends going into a restaurant. A beat cop in casual conversation. Knowing he’s in danger, Richards convinces himself that everything is dangerous. It’s well handled and effectively frightening, because once you start to suspect the benign, there’s no escape from the horrors of your own imagination.

It’s undercut by the fact that Richards is correct — the Hunters are indeed surrounding the building and about to ransack it — but that’s just further evidence of King writing well and not realizing it.

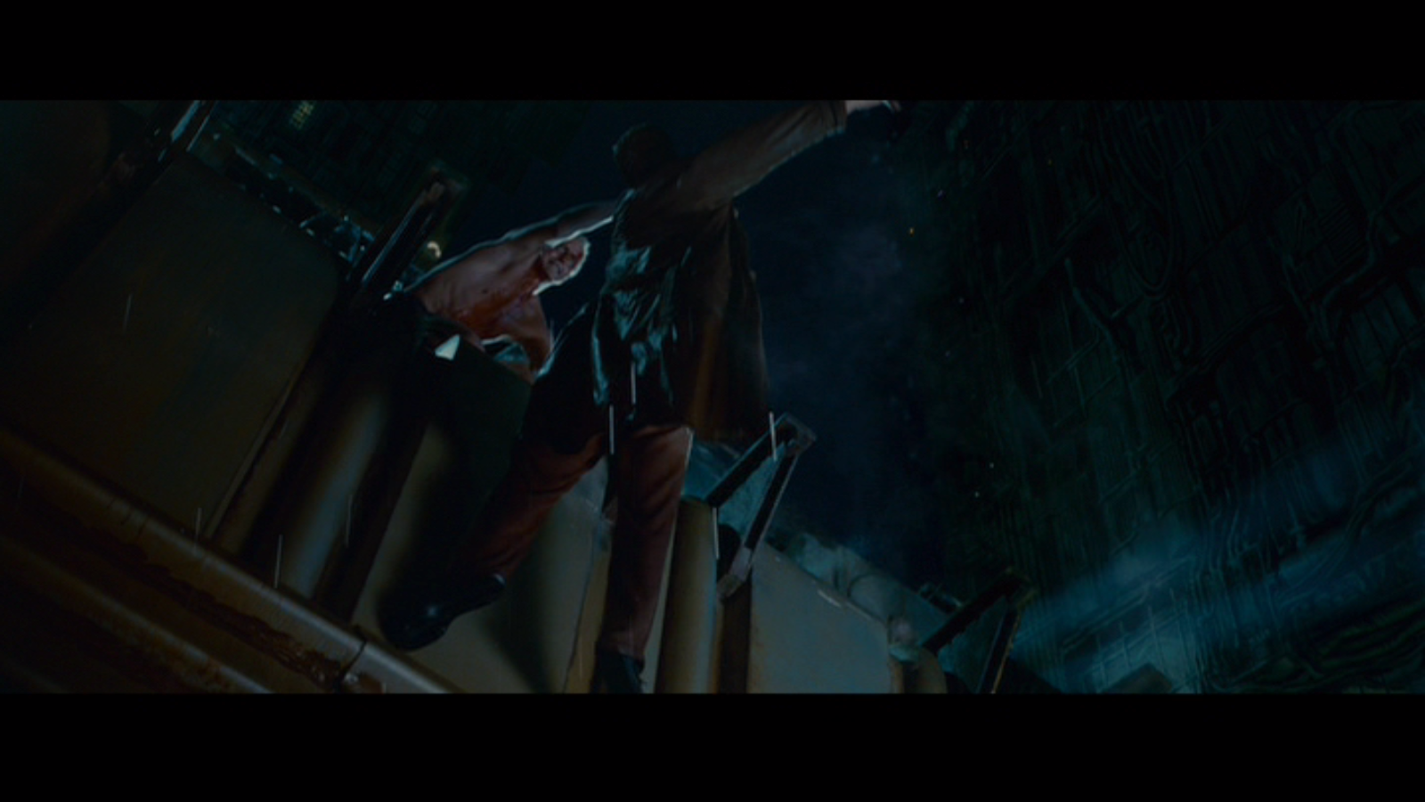

In the film, there’s no such paranoia. Schwarzenegger doesn’t have to worry about who might possibly be a Stalker…it’s probably that guy with the flame thrower screaming and throwing flames everywhere. Or it’s the guy covered in Lite-Brite pegs shooting electricity out of his hands. The novel version of Richards has to rely on his wits alone, and the film version just needs his brawn. It will always be remarkable to me that in the transition from page to screen, one type of character will become, in the blink of an eye, that same type’s polar opposite.

King’s version of Richards relies on a combination of desperate resourcefulness and dumb luck to escape his various predicaments. Glaser’s version beats things up and delivers ostensibly witty one-liners.

After killing the first Stalker, Schwarzenegger turns to the camera and says, “Here is Subzero. Now plain zero.” After chainsawing Buzzsaw, Schwarzenegger quips, “He had to split.” Fireball gets the luxury of two puns about his horrifying death; Schwarzenegger says, “How about a light?” before setting him on fire, and “What a hothead” immediately after.

All of this would be fine in any other interchangeable action movie, but probably not one in which Schwarzenegger is supposed to be playing a man framed for a violent crime he didn’t commit. I understand that the circumstances are very different, but if this version of Richards wants to convince the world he didn’t open fire on unarmed civilians, he probably shouldn’t take such obvious delight in murdering people by chainsawing through their genitals.

Yes, unlike the downtrodden Richards of the novel who has no other way of providing for his family, this version of Richards was some kind of cop. He’s given the order to kill a group of defenseless civilians and refuses, but his fellow officers overpower him and obey the order. (Exhibit G that Schwarzenegger was miscast: The film opens with a bunch of wimps beating him up.)

Some doctored footage is all it takes to make the world think that Richards chose to defy orders by killing the civilians, and his fellow officers tried to stop him.

It’s a bit strange, though, that a policeman in this police state doesn’t actually realize that he lives in a dystopia until this moment. We’re shown that the world (or at least America) has long fallen into this shitty situation where the poor are repressed and criminals are executed for our entertainment on live television, but Richards is shocked to receive orders to do something untoward.

“I said the crowd is unarmed!” he barks over the radio after being told to kill them. “There are lots of women and children down there!” Did Richards somehow decide to become a police officer, complete all his training, and begin his career in law enforcement without ever realizing that he was working for Big Brother? Richards is painted as an uncommonly moral human being in this cruel, inhumane future, but if that’s the case, why did he knowingly sign up for the Schutzstaffel?

A great piece of media that understands this and serves as a nice counterpoint is The Last of Us. At the very beginning of that game, a soldier gets the order to execute a little girl and her father who are attempting to flee the city. He has a short, nervous exchange over his radio to confirm that this is actually the order…that this is actually what they want to do. The game then pushes us 20 years into the future, and soldiers aren’t asking questions anymore. If they’re told to kill someone, they kill them, because it’s no longer an unfamiliar order. Confused reluctance only has a home at the very beginning of this process…not years deep into it.

Perhaps Richards joined up knowing that the police were corrupt, but intended to be one of the good guys and maybe effect change from within…but he can’t have been surprised to receive an order he disagreed with in that case. How did this conflict never come up before? How did Richards never even anticipate the conflict? He comes across looking far less like the One Pure Soul than he does like David Mitchell asking, “…are we the baddies?”

The movie is oddly filled with moments like this, in which people who live in this society seem to be surprised and confused by it, as though, you know, they weren’t adults who watched it get to this point and have lived in it for at least two years, based on the opening text.

In the novel, flawed as it is, King’s characters react more appropriately. Memories of a freer, better past have been more or less completely lost, with loose fragments of history passed around like parables among people who can no longer understand it. Otherwise, this is what the world is, this is what the characters have known, and they don’t question it any more than we in reality question our own societies. We don’t ask why someone on TV spins a wheel and solves word puzzles for money, and they don’t ask why someone signs up to flee a squad of hitmen across the country. They’ve become equivalent. At that point, King knows, people stop questioning it. That’s the real horror.

Glaser, by contrast, doesn’t seem to realize that none of this is new to these characters, and so they shouldn’t comment upon it and question it as though it is. It’s as though all of his main characters recently suffered severe head injuries.

Late in King’s novel, Richards forces himself into a vehicle with a woman named Amelia Williams. She’s something of a hostage who Richards does indeed use as leverage, but King wants us to remember that Richards doesn’t steal her away because he’s a bad person; he does it because he’s a desperate person.

A desperate person who bullies her, browbeats her, makes her cry, ogles her tits, and eventually causes her to be sucked out of a moving airplane, but absolutely not a bad person, and I can’t possibly see how you might mistake him for one.

In the film, we meet her equivalent much sooner. Here she’s Amber Mendez, and she’s played by María Conchita Alonso, who you may remember from every other movie from the 1980s that wasn’t worth seeing.

I mean no disrespect to Alonso as a person. From what I understand she, like Schwarzenegger, has a large number of great qualities to offer the world. Also like Schwarzenegger, acting was never one of them.

In the film, Richards is incarcerated for his crime of disobeying orders. He shoots his way out of prison, killing dozens of guards as he does so. (Murder is perfectly fine in Glaser’s version, except for the one very specific time that it isn’t.) Once he’s out he flees to his brother’s apartment and finds it occupied by Amber Mendez instead.

In this scene, Schwarzenegger and Alonso carry on a long exchange that makes it sound like they’re both still learning English from flashcards. It’s atrociously acted, even in comparison to the writing which was already pretty darn poor. But, of course, we know that our two leads were not hired for their ability to inhabit a character.

Schwarzenegger was hired because he was a bankable name at the box office. Alonso was hired because…

Yeah. The first we see of Amber is her return from work. As all of us do, she removes her shoes when she gets home. As only she does, she takes everything else off and puts on sexy lingerie to work out in.

Alonso is an attractive woman, and The Running Man makes clear that that’s all they wanted from her. As soon as we see her, the filmmakers rush her out of her clothes. When we see her later, they rush her into a low-cut, skin-tight onesie. Between those two points we hear other characters complimenting her ass.

Richards — introduced to us as the lone virtuous soul in this ruined world — breaks into her apartment and immediately ties the half-naked woman up and starts going through her things. It’s actually pretty uncomfortable to watch, as I’m pretty sure this is any single woman’s actual nightmare.

The film tries to play them like a sort of mismatched romantic comedy team, with their bickering only barely masking the sexual tension they feel that indeed is resolved when the film ends. Only Richards destroys her belongings, steals from her, kidnaps her, and threatens multiple times to murder her in cold blood. Oh, and we’re supposed to see Amber as the bad guy when she turns him in so she can escape. What a bitch, eh guys?

Of course, problematic handling of female characters is something of a King trademark, along with every black character’s dialogue being rendered so that it sounds like it’s been transcribed from Song of the South, so maybe this was just Glaser’s loving nod to the source material.

My favorite bit of offputting King horniness comes during one of Richards’ pre-show exams:

On the table was a sharpened G-A/IBM pencil and a pile of unlined paper. Cheap grade, Richards noted. Standing beside all this was a dazzling computer-age priestess, a tall, Junoesque blonde wearing iridescent short shorts which cleanly outlined the delta-shaped rise of her pudenda. Rough nipples poked perkily through a silk fishnet blouselet.

Lifehack: If you’re in a kinky relationship and need a safe word, try “pudenda.” Not only will your partner stop what they’re doing immediately, but they won’t even want to think about sex for a week.

This is the description, I remind you, of a test proctor. Not that it would be any less disgusting if he were describing a prostitute that a character were about to have sex with, but at least such a description might serve a purpose there. Here it’s just ogling.

Admittedly, Richards seems to believe she was sent in as some kind of test herself…a sexed up babe to distract him or confuse him or actually he didn’t think this through any better than King did so forget it.

If that is her role, though, it doesn’t make sense that she’d bristle and quickly turn emotional when he called her on it. And if it’s not, then Richards has no right to belittle her the way he does and make her feel like a cheap piece of meat.

“You go out and have a nice six-course meal with whoever you’re sleeping with this week and think about my kid dying of flu in a shitty three-room Development apartment,” he tells her, immediately after groping her in a way that she makes clear is unwelcome.

It would be nice to say that the racism and misogyny (among other issues) are built into Richards as character flaws, problematic traits with an actual artistic or narrative purpose. But they aren’t; this is just the way King writes. To read his work is to grit your teeth in unhappy anticipation of the next time he plunges you into an unnecessary, detailed description of somebody’s penis or vagina. And there is always a next time.

Amber’s role here is a bit different from Amelia’s in the novel. In the novel, Amelia was just pulled along for the ride. (Twice, because King let her go at one point and forgot he needed her for a later scene so he dragged her back into the fray.) In the film, Amber gets Richards arrested again, but notices that the news coverage of the event doesn’t match up to what she actually witnessed.

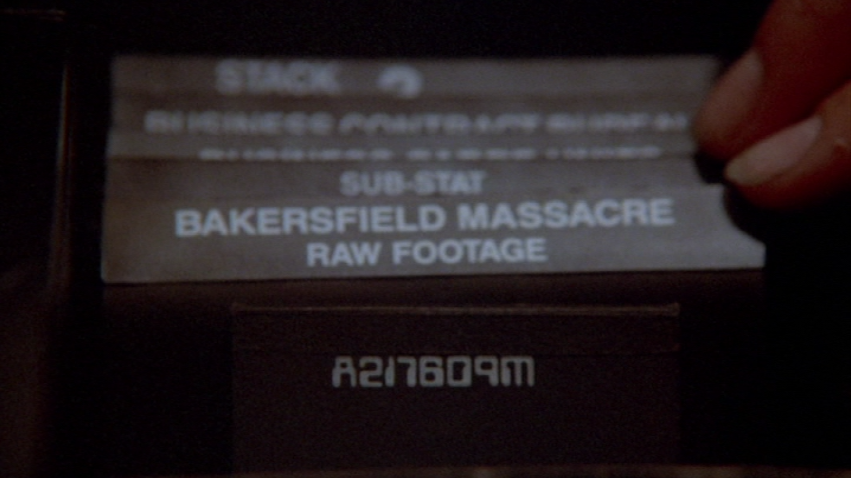

She begins snooping around the network and finds the original, unedited footage of the exchange between Richards and his superiors that opened the film. Boy, it’s a good thing that this evil corporation clearly marks the evidence that will bring it down and keeps it in an unlocked drawer in an unguarded room.

Well, it’s probably better than keeping your satellite uplink in the middle of Thunderdome, but still.

Amber has access to the network building because she’s employed by them; she works as a composer for their shows. The fact that any movie could introduce this detail and then somehow not show us her process for composing the incidental music for a game show in which contestants get torn apart by dogs is outrageous.

Again, though, Amber shouldn’t have to (or even be able to) discover the fact that the network lies. If she didn’t work there, sure. But because she does work there — and is there every day, and has access to rooms such as this — it can’t be a revelation. Just as Richards shouldn’t be able to realize in the middle of a mission that his superiors aren’t making the most ethical decisions, Amber shouldn’t be able to realize in the middle of a workday that her organization lies. Her organization’s business is lies. That’s what they do. That’s all they do. They mislead and misinform.

As an employee, she shouldn’t be unaware of that fact. If the network truly tried to hide from everyone who works there that they spread untruths, it would crumble immediately. One leak, however minor, would bring the entire thing down. Instead, an organization like this has to convince its employees that lying is the best thing for them to do. That it’s a small transgression in exchange for some greater good. That it’s better, for any reason, to lie to the people who turn to them for information.

Consider O’Brien in Nineteen Eighty-Four. He knows The Party is lying to the people. He has to know that, because he’s employed by them. He doesn’t capture and torture and reprogram Winston because Winston was incorrect; he does it because he was correct, and O’Brien believed the lie was necessary.

If The Party attempted to hide from its own members what they were doing, we never would have had Nineteen Eighty-Four; The Party wouldn’t have survived long enough for there to be a story. Instead, it had to convince its members that wrong was right. The network in this film could learn a lot from Orwell.

Amber is caught and tossed into the Game Zone with Richards and two other runners. She does nothing, but much later in the film a Stalker tries to rape her, so I guess that’s nice. If only he would have first broken into her home and tied her to the furniture she might have ultimately warmed up to him.

When Richards strangles and kills Subzero (“He was a real pain in the neck”), much ado is made of the fact that a Stalker has died on the job. Evidently, this has never happened before. At least, that’s what we’re told.

But we know that two other contestants are said to have won The Running Man in the past. (This is in notable contrast to the novel, in which we are assured that nobody has ever won.) Of course, the freedom of those two winners is revealed to have been faked; they were executed behind the scenes instead. That’s fine, but how did those episodes play out for the viewers at home?

If those winners didn’t kill any of the Stalkers and also didn’t get killed themselves, I assume that means they just survived for three hours. So were those episodes just three-hour slapfights in which neither party fell over? It feels like a bizarre holdover from a different version of the script, as does Captain Freedom — Jesse “The Body” Ventura — being described as “undefeated.” Wouldn’t every Stalker be undefeated if none of them ever died in this bloodsport before tonight?

Eventually Schwarzenegger beats up enough people that the movie needs to end, so he makes his way onto the stage to confront Killian directly.

In a way, this is the climax of the novel as well. There, Richards hijacks a passenger plane and flies it into the massively tall headquarters of the Games Network, presumably killing everybody inside and huge numbers of innocent people all around it. “It rained fire twenty blocks away,” King assures us. He also assures us that good Ben Richards got to see a look of horror on Killian’s face through his office window as he gave him the finger and plowed the plane directly into him.

Richards died as he lived: disrespecting black people.

In the film, Schwarzenegger takes a more hands-on approach to dealing with Killian. And Killian gets a decent — though certainly not great — little speech to go out on.

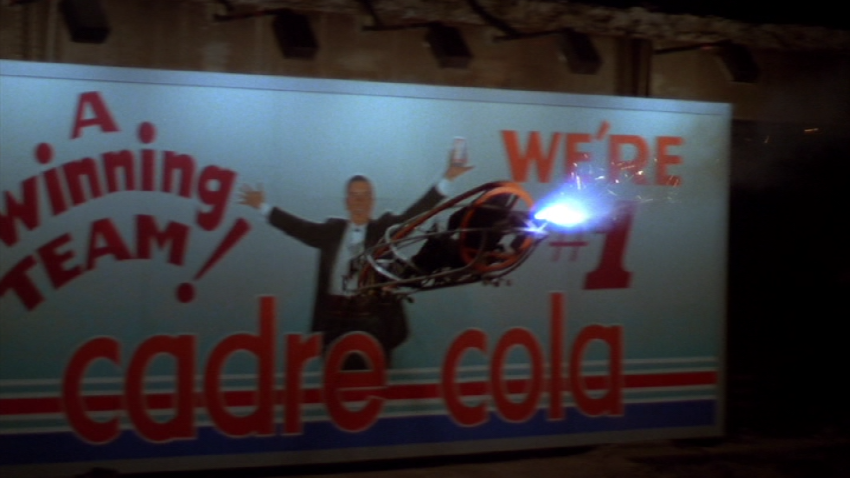

“For Christ’s sake, Ben,” he says. “Don’t you understand? Americans love television. They ween their kids on it. Listen, they love game shows, they love wrestling, they love sports, and violence. So what do we do? We give ’em what they want. We’re number one, Ben, that’s all that counts.”

Any credit I could give the movie for this speech is negated by the sheer stupidity of Killian delivering it to Richards over the chute that leads to the Game Zone, as a shuttle is actively loaded into it, making it impossible to focus on anything other than the remarkable clumsiness with which the film is setting up its conclusion.

Sure enough, Richards stuffs Killian in the shuttle and fires him down the tube.

Which…shouldn’t really be a big deal. The Stalkers are all dead, so can’t Killian just get out of the shuttle and work his way back up through the backstage areas?

Oh, I guess Richards somehow knew that this time — like no other time — the shuttle would hit a wall and explode, raining bits of Killian twenty blocks away.

The shuttle even does Richards the courtesy of crashing directly through a Cadre Cola billboard with Killian’s face on it so that Schwarzenegger can say, “Well, that hit the spot.”

In both versions of the ending, the everyman takes down the network and kills its figurehead. In the film, though, all sense of personal sacrifice is lost. One version of Richards dies along with everyone else responsible for running the Games Network. The other wanders off to fuck María Conchita Alonso.

The Running Man is a terrible film based on a pretty lousy book, and it’s disappointing for just how mindlessly it squanders its potential.

King’s idea was fine. Swap in some better characters and do the concept justice, or at least play into the ridiculousness a little bit more. For a movie with a wisecracking action hero, The Running Man is rarely any fun. When it is, it feels for a fleeting moment like you’re watching a different film entirely.

Had Glaser done more along the lines of the Climbing for Dollars commercial and Captain Freedom’s workout video, putting together a grander, funnier, more cynical pastiche of entertainment culture, employing the exact same superficial glitz and unapologetic appeals to the viewer’s base instincts that it’s satirizing, we could have gotten a pretty good film. It wouldn’t have been The Running Man, no, but what we got wasn’t The Running Man, either.

Honestly, I have to wonder why they bothered paying for the rights to The Running Man at all, if it was to share so little with its source material. The central game is completely different, with its own rules, presentation, and rewards. Change the name of the main character and the name of the game show and it would be impossible for anyone to sue for copyright infringement. Actually, you could probably even keep the main character’s name. With literally nothing else taken from the novel, “Ben Richards” is common enough that you could argue it’s coincidence.

Of course, the answer is that they licensed the rights to the novel because Stephen King’s name is worth something to moviegoers, but King successfully lobbied to have his name withheld from the film and its promotional materials.

Watching The Running Man is a strange experience after having read the novel, if only because it seems unnaturally driven to squander even more potential than King did. It’s not an especially fun movie and it’s by no stretch of the imagination a good one.

And as much as I love (and I do love) Richard Dawson’s performance, I can’t say it’s worth watching even for that.

Maybe he should have directed the movie. He’s certainly the only one who understood what it was about.

The Running Man

(1982, Stephen King [as Richard Bachman]; 1987, Paul Michael Glaser)

Book or film? Book

Worth reading the story? Yes. It’s flawed but engaging.

Worth watching the film? No, with the notable exception of one great performance.

Is it the best possible adaptation? Not a chance.

Is it of merit in its own right? It gives the middle finger to and plows a plane right through merit.