I want to love Mega Man 3. I really do. It’s often spoken of in the same breath as genuine classics. It’s rarely criticized for anything other than superficial reasons. It’s adored, with many fans holding it up in comparison with Mega Man 2, as though it’s impossible to declare which of these great games is better.

I will declare. Mega Man 2 is better. And I don’t see how Mega Man 3 can even compete.

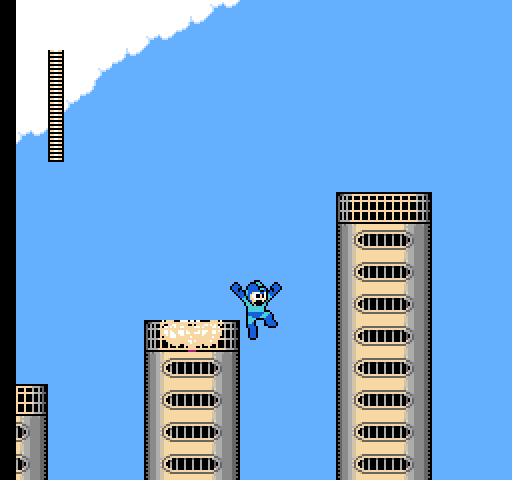

But I want to love it. I really do. Mega Man 3 does so much right. It introduced the slide, which is now a distinguishing feature of Mega Man’s moveset, and which so elegantly adds an entirely new wrinkle to navigating stages and avoiding enemies. It introduces not one but two great new characters: Rush the utility dog and Proto Man, our hero’s moody and conflicted older brother. On top of that, its soundtrack contains some of the best tracks in video game history.

And yet…it’s not a great game.

It might be a good one. It probably is.

But it’s not great. It’s flawed and unbalanced. It’s glitchy and in some cases more rickety than the first game was. It’s a step backward when it had all the potential of being another great leap forward.

And so as much as I want to love Mega Man 3, I don’t. I can’t. And this is probably going to be the saddest review of it you’ll ever read.

By the time Mega Man 3 was released, I was already a firm acolyte of Mega Man 2. My friends and I played it endlessly. We designed Robot Masters and stages of our own. (One of mine was VCR Man. He probably wielded the weapon Planned Obsolescence. My friend Jimmy asked why they all had to be Man. Why not Woman? It would be decades before he got his wish.) I even bought and read that terrible Worlds of Power novelization.

So, no, I wasn’t looking at Mega Man 3 with an objective viewpoint. (Worth repeating: as an individual forming an opinion on somebody else’s work of art, that would have been impossible.) But neither was I closed off to it. In fact, I liked Mega Man 3 a lot more then than I do now. It’s only time and reflection and a greater capacity for articulation that I’ve come to realize how…disappointing it really is.

It’s not, however, a game devoid of new or interesting ideas. In other words, it’s not disappointing in the standard way that sequels are disappointing, in which the same beats are repeated to diminished returns. Mega Man 3 pushes itself, and does some truly fantastic stuff along the way.

Where it falls down is in its execution, and that represents its step backward. Whereas Mega Man 2 proved that the developers had the potential to refine their ideas to incredible, unforgettable degrees, Mega Man 3 slid right back into Mega Man territory…throwing so many new ideas around that none of them feel complete.

I know, I know. Who am I to say any of this? Don’t people love Mega Man 3? Isn’t it highly regarded? Isn’t it a classic video game?

It is. And I’d never attempt to take those accolades away. But I do think that Mega Man 3 is a better game in our minds and memories than it is in reality.

I want to love Mega Man 3. I want to adore it. I want to be able to say that it took every ounce of merit from its predecessor and enhanced it.

But I can’t.

I try, and I try, and I can’t.

I can say a lot of things in its favor. I can make a list of all of the things it gets just right. I can gush about stage tunes like Gemini Man, Top Man, Magnet Man, Shadow Man, and Spark Man all night long. But then I play the game, as I have to, and it find it impossible not to trip over its mistakes. Impossible not to question its design philosophy. Impossible not to…wish I was playing almost any other game in the series.

I know. I know.

I’m a terrible person.

But let’s focus on the good up front, because Mega Man 3 has loads of it.

My favorite thing about the game — aside from its stellar soundtrack — is a brilliant, tiny tweak that a lot of people probably don’t even notice started here. In first game, Mega Man would defeat a Robot Master, pick up a mysterious object, and get bumped back out to the stage select. It was up to the player to pause the game in the next level to see that they had a new weapon…which I’m sure many early gamers overlooked entirely. Mega Man 2 made the acquisition of weapons more explicit, with some text (and a pulsing beat) explaining what you got.

That’s fine. That’s more than fine. In fact, that small improvement was all we needed.

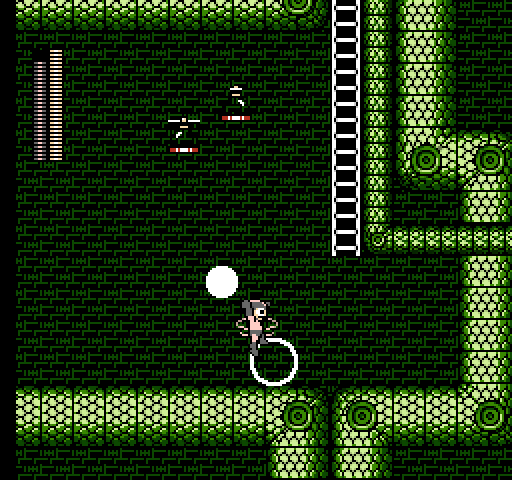

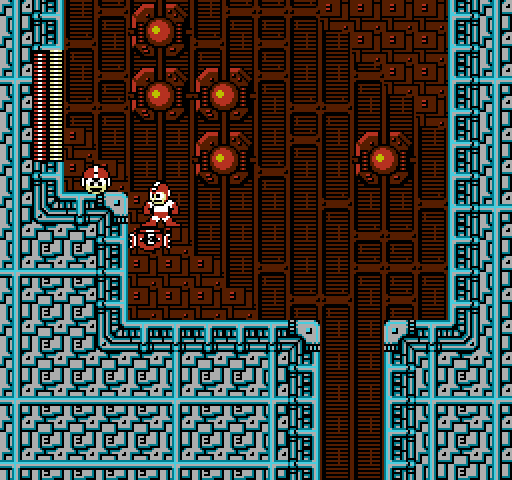

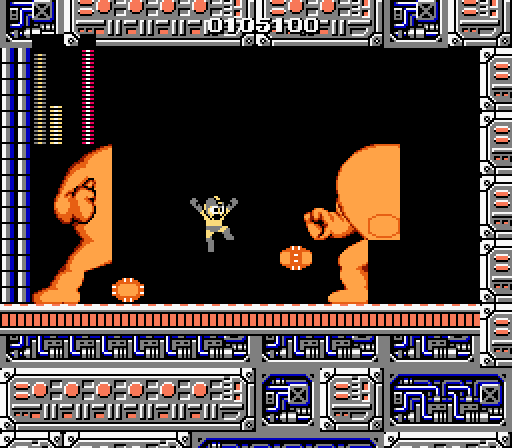

But Mega Man 3 does it so much better. Now Mega Man stands alone in the empty boss room for a moment, then leaps into the air and is showered with swirling particles. In fact, it’s the same effect used by the Robot Master (and Mega Man himself) when he explodes…only now it’s reversed and directed inward. It’s a perfect visual indication that somebody has lost the duel, and somebody has won. To the victor literally go the spoils.

Then the pause window pops up so that you can see a new weapon in your inventory, at which point its energy bar noisily fills…tempting you to rip right into your new gift and start experimenting with it. It’s great. It’s a lovely tweak to the stage-ending sequence, and it’s the best celebratory moment the series has offered us yet.

And then we get a great splash screen with Mega Man caught mid-leap (always the best way to catch a Mega Man sprite, as our history of jumping through boss doors has empirically proven) and yet another fantastic, searing song blazing in the background. It’s a longer song than you probably realize, too; let the screen sit for a while and enjoy it.

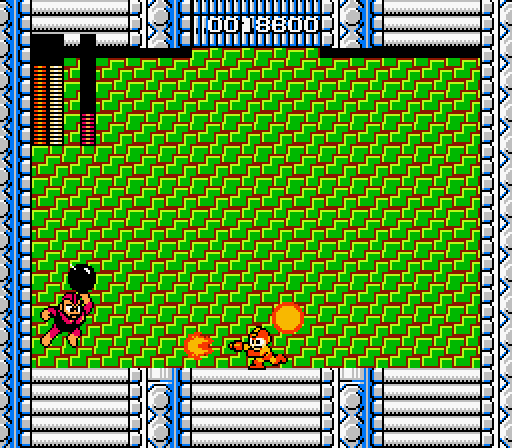

But there’s a dark corollary to all of this incredible, impressive, weapon-get bombast…and that’s the fact that the weapons absolutely stink.

None of them feel very fun to use, and in a game that’s built around experimentation, that’s a real problem. What’s more, they’re often buggy, lending them an air of carelessness that makes you wonder why you’d want to play with them if the developers didn’t bother properly coding them.

Of the weapons, the Shadow Blade is probably the best. It’s essentially a Metal Blade crossed with a Rolling Cutter, and that’s a good thing, because those weapons were great. Its range isn’t wonderful, but it’s still the one weapon worth using. And there’s the Needle Cannon, which is more or less innocuous. It’s a differently shaped Buster pellet, and hardly fills the mind with possibilities. Present, but inoffensive.

Then there’s…the rest.

The Magnet Missile is great when it works, which it often doesn’t. Its intention is to home in on enemies, but it will many times miss them entirely or phase right through them without causing damage. The Hard Knuckle crawls so slowly across the screen that it’s literally always faster to kill enemies with your basic weapon, even when they’re technically weak to the Hard Knuckle. The Search Snake makes some snakes. Nobody cares.

The worst are the Spark Shot and the Top Spin. The former just freezes enemies in place, much like the Ice Slasher, but this time Mega Man can’t switch weapons to kill the stunned enemy; all you do is freeze enemies in your own way. It’s awful. The Top Spin is just odd; it’s a pirouette Mega Man can only perform in the air, and it’s a crapshoot whether you or the enemy you strike takes the damage. And how much damage. And how much weapon energy it uses. If you wanted evidence that Mega Man 3 has sloppy coding, look no further. (Having said that, though, once you get the Top Spin you really should spin through the boss doors at least once.)

The most puzzling is the Gemini Laser, which introduces so much lag to the game that it’s almost unusable, and there’s no excuse for that. While Mega Man and Mega Man 2 both lagged at various points, it was always understandable; so much was happening on the screen that of course the little NES would struggle to keep track of it all. With the Gemini Laser, all you’ve done is fire a weapon. You know. Your primary way of interacting with objects in the game. The lag is inexcusable.

We spoke for a bit in Mega Man 2 about how the weapons were given a layer of nuance by allowing them to do things other than fly straight forward when the B button is pressed. Mega Man 3 takes this a step backward, with much less — and much less interesting — complexity.

In this game, only three weapons allow for any degree of adjustment. The Shadow Blade can be thrown in many directions, like the Metal Blade. So far, so good. The Hard Knuckle can be steered slightly up or down by pressing the appropriate direction on the D-pad after firing, and the Needle Cannon can be rapid-fired by holding B.

And that’s it.

The Top Spin does at least ask the player to think differently about how to use it, as you need to press A to jump and then press B while in the air, but no player should ever be using the Top Spin so that doesn’t really count.

Storywise Mega Man 3 doesn’t offer much that the previous games did not. There are some bad robots, and Mega Man is a good robot who kills them off one by one, then smacks their boss around for a bit.

It’s with this game, though, that I’d argue that Dr. Light goes from trusting to learning disabled. In Mega Man Dr. Wily betrayed Dr. Light, turned all of the robots they designed together evil, and set about destroying civilization. In Mega Man 2 Dr. Wily, unprovoked, built eight evil robots for the sole purpose of destroying civilization. In Mega Man 3, Dr. Light helps Dr. Wily build an enormous robot to protect civilization, but doesn’t bat an eye when Wily asks for the keys and offers to go get it washed.

There’s seeing the best in people, and then there’s seeing nothing at all. Dr. Light is a boob.

The truly unimpeachable things that Mega Man 3 brought to the table are the two new characters, and we can learn a lot about the value of strong characterization from both of them.

Prior to Mega Man 3, there was a simple triumvirate. Dr. Light (appropriately mistranslated in this game as Dr. Right) is the good scientist, Dr. Wily (irrelevantly mistranslated in this game as Dr. Wiley) is the bad scientist, and Mega Man is the player’s avatar, advancing the cause of one and beating back the cause of the other.

It’s easy, and a pretty common video-game setup: there are forces of good and forces of evil, and you’re the middleman. (Middle Man 3)

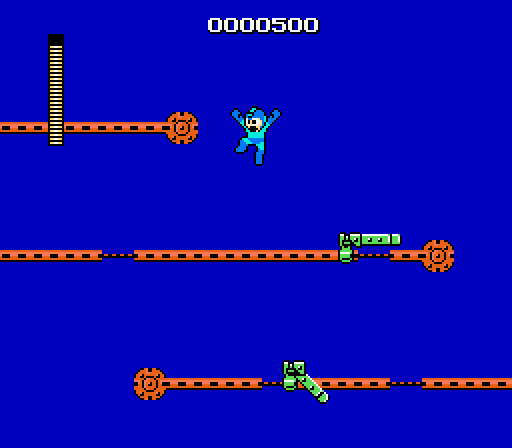

This game adds the first wrinkles to that formula with two new, important characters: Rush and Proto Man.

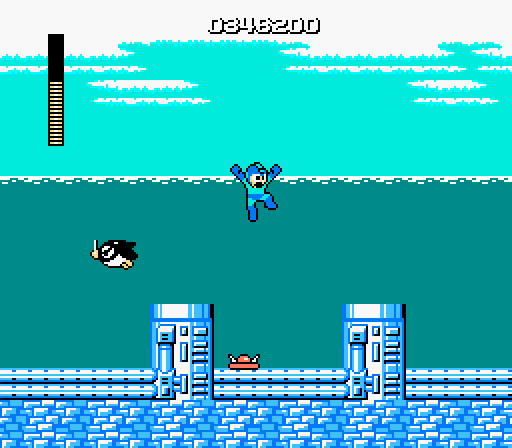

Rush is essentially just a charming face slapped on Mega Man’s utilities…but it’s a change that matters. The simple fact that these gadgets now resemble a dog makes them feel more important, and more significant to our hero. They’re not stepstools this time; they’re a friend.

While the Magnet Beam was something like a panicked afterthought in the first game, Mega Man 2 made its Items feel natural and better designed for the gameplay. Mega Man 3 goes a remarkable step forward by giving them personality. And the best part is that it’s entirely implicit.

Does Rush Coil function any differently than a springboard would have? Of course not. But by giving it a proper name (as far removed from Item-4 as it’s possible to get), we give Rush a sense of individuality. By further making Rush a dog, we tap effortlessly into the implied relationship between a little boy and his beloved pet. (Mega Man’s youthful appearance in the sprite art becomes an immediate benefit at this point.) And by adding the slightest flourishes — such as having Rush’s tail wag briefly when you select him from the menu — we believe in Rush.

The Magnet Beam was a thing. Item-2 was a thing. Rush is a dog. Mega Man 3 figured out how to make players genuinely care about a utility decades before Portal faced the same question.

The fact that we actually see Rush transform in three ways in this game (Rush Coil, Rush Jet, and Rush Marine) future-proofs him as well; if the then-hypothetical Mega Man 4 didn’t require any of those things, Rush could simply transform into something else. Like a real dog, Rush wouldn’t be a disposable fancy; he was now part of Mega Man’s family.

And speaking of family…

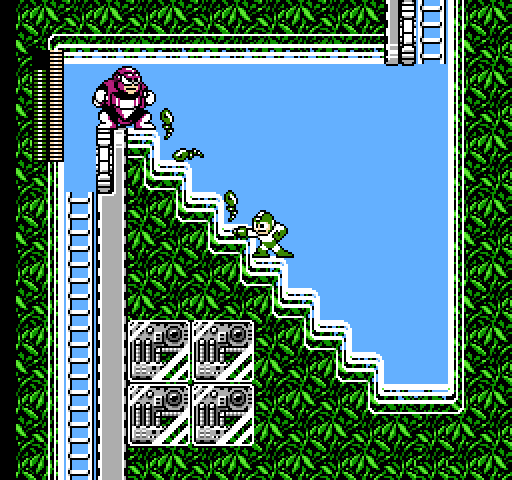

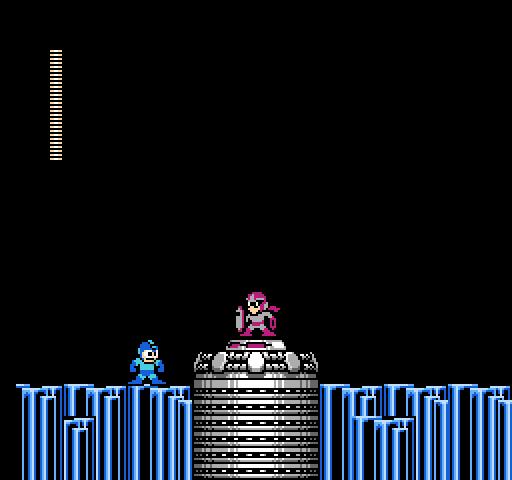

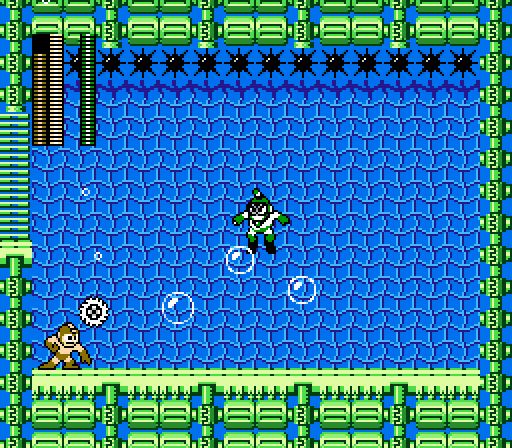

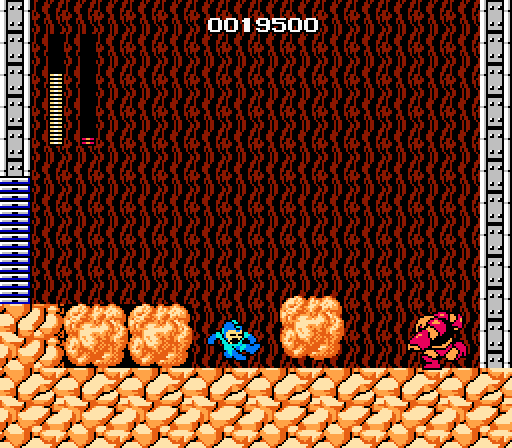

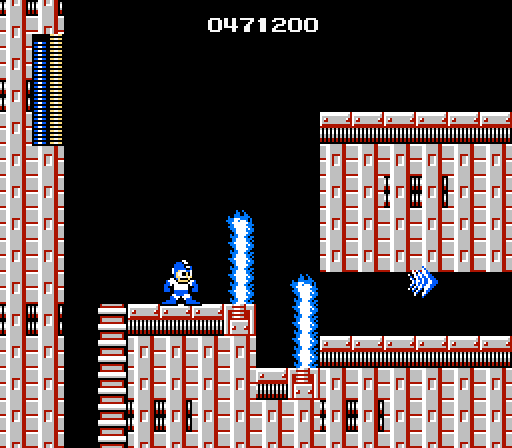

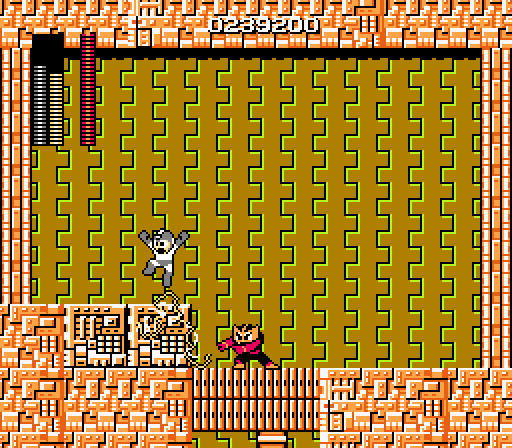

Proto Man. Boy. Is there a cooler character from the 8-bit era? Proto Man with his cape and permanent shades probably holds the title pretty securely.

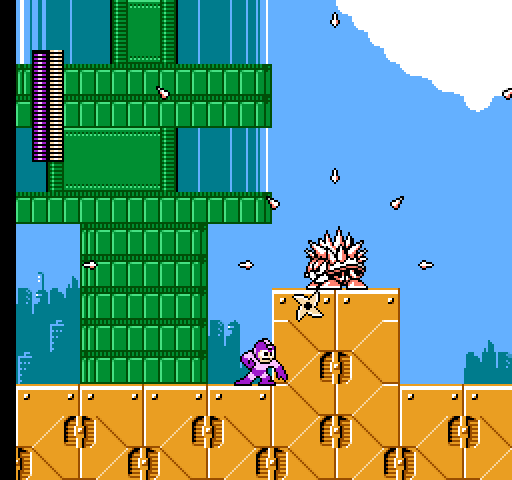

There’s an air of mystery about Proto Man that runs through the game and makes his story — whatever his story may be — far more compelling than any kind of idiocy Dr. Light is engaging in with Dr. Wily. He turns up in four of the main stages, each time accompanied by his distinctive whistle. (Which you can hear right now, I’m certain.)

I remember each of these appearances being thrillingly tantalizing to my young self. I remember arguing with friends about them. Who was this guy? Was he a bad guy? Was he helping us? Was he testing us?

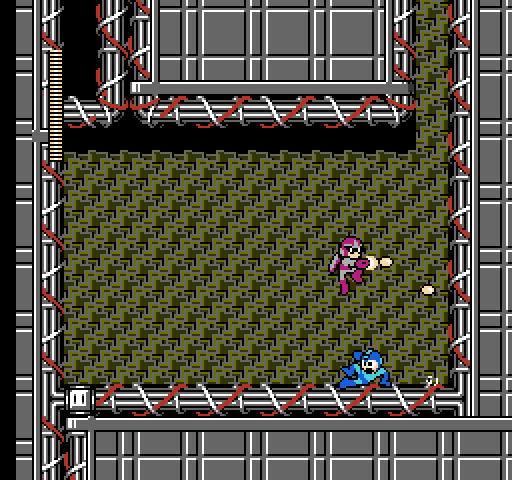

It was strange. In three of his appearances, Proto Man does actually attack Mega Man…but he always seems to be holding back. He doesn’t do much. He hops around and fires, but most of the common enemies are better at getting in hits than Proto Man is.

But Proto Man keeps appearing. He feels meaningful in a way that other recurring enemies don’t. Those, after all, are destroyed when you defeat them. Proto Man, instead, teleports away and clears a path forward for you. There’s something deliberate behind his behavior. Other enemies are programmed to defeat Mega Man, and so they fight to the mechanical equivalent of death. Proto Man, clearly, has something else in mind.

Most intriguing is his appearance in Gemini Man’s stage. There he doesn’t fight you. He could — and he might be considering it — but he doesn’t. He just…stares. He watches you. He stands motionless. Sizing you up? Questioning you? Respecting you as an equal?

We’ll never know, because he opens the path forward and leaves without a word. Without firing a shot. Without anything but his somber whistle.

…and that’s it. There’s a fight with him after the Doc Robot stages (in which he’s referred to as Break Man…perhaps another mistranslation), and then he saves your life when Wily’s castle crumbles at the very end. That’s all we really know.

Until we finish the game and watch a scene marked EPILOGUE.

We see identification cards for each of the robots Dr. Light built in Mega Man. They run backward. Elec Man. Fire Man. Bomb Man. Ice Man. Guts Man. Cut Man. Then the good guys we already know. There’s Roll, Mega Man’s sister. And Mega Man himself.

And, finally, the mysterious Proto Man, revealed in a note as being “brother of Megaman.”

It’s the closest thing to a true twist ending any Mega Man game has had, and it’s a good one. It forces us to reconsider the events of the game, yet doesn’t definitively answer any questions.

Was Proto Man fighting Mega Man to make sure he was prepared for what’s to come? Possibly, as he removes barricades in four stages that Mega Man would not be able to remove on his own. Or was he seeking some kind of revenge? This is also possible, as Proto Man will gladly enough kill Mega Man should the fights go that way. Which may be telling; Proto Man won’t fight to his own death, but he’ll sure as hell kill his brother.

He eventually saves Mega Man from Wily’s crumbling castle, yes, but does that mean all is forgiven? Does that even mean he likes his brother? Does he feel obligated to save him? Hell, does he regret saving him?

The answers are never quite revealed, no matter how long Proto Man has remained a series staple. And I like that. I like that we never truly know the depth of his allegiance. And I like that his story is almost entirely implicit, hinging on a single, loaded line of text at the end of the game. A sibling rivalry. Father issues. Conflicted loyalties. All suggested, but never divulged.

His Japanese name — Blues — speaks even further to his sad demeanor, and is much more evocative than his Western name, which is just a clue that he came first.

Proto Man is by far the richest of Mega Man’s characters, if only because he’s the only one who can’t be fit into a box. Dr. Cossack in the next game similarly straddles the line between good and evil, but once his motivation is revealed it’s impossible to see him as anything except firmly on the side of good.

Proto Man…well, we still don’t know about Proto Man. He was never used again as effectively as he was in this game, but that’s okay. Because…well…how do you top that?

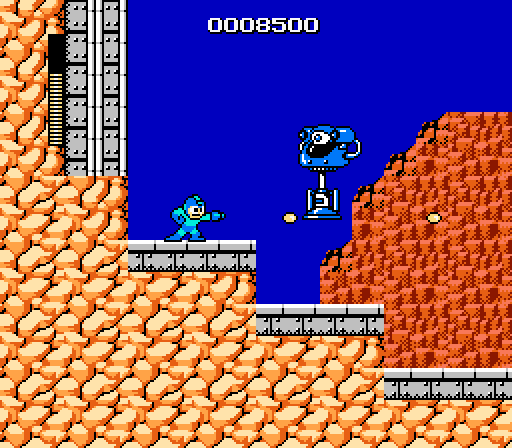

But Mega Man 3 isn’t about Proto Man. As much as we can debate the merits of individual games, or weapons, or items, or characters, or plots, the entire Mega Man series is really about one thing: boss battles.

That’s something I never quite realized as a kid. Sure, I liked certain Robot Masters more than others, but I was never quite sure why. I tended to be drawn to the explosion-based Robot Masters, as you can probably tell, even though I hated using their weapons. I kept coming back to Bubble Man often enough that he was the first one I learned to outwit. I couldn’t stand fighting Gemini Man, but he was clearly so cool that I couldn’t dislike him.

The Robot Masters — by and large Mega Man’s bosses — were distinct. They had personality, even if it was entirely implied by their music, their stages, their arsenal, their speed, their agility, their aggressiveness.

Metal Man wouldn’t make a move until you did, for instance…unless you took too long, in which case he’d lash out in boredom. Guts Man would stun you by stomping the ground and use that opportunity to close in, fencing you into a corner. Heat Man pelted you with a volley of fire the moment the fight started, not letting you so much as blink before he’s on the offense.

Other Robot Masters, though, such as Magnet Man and Snake Man in this game, just barrel from one side of the screen to the other, working through their routines as though you’re not even there, secure in the knowledge that they’ll successfully bulldoze you before you learn to fight back.

As a kid, I never realized the distinction in fighting style. It’s hard to realize it when you’re struggling just to survive. I’d run at an enemy, guns blazing. Hopefully the enemy died before I did. When possible I’d dodge return fire, but I was both panicked and unskilled enough that this wasn’t reliable. I’d fire wildly and hope for the best. Once I got a special weapon, I’d find whatever Robot Master I could and pelt them blindly with that instead.

As an adult, it’s different. I don’t use special weapons often — aside from the capsule room refights and some of the more particularly irritating bosses — because I realize now that these are a series of duels. It’s not about showering the room with projectiles; it’s about watching, reacting, learning, responding. It’s about identifying and anticipating patterns. It’s about the graceful exchange of attacks and retreats.

And there really is something beautiful about Mega Man’s better boss fights. When you learn how to fight a Robot Master — not beat, but truly match wits with — it becomes a thing of elegance. Of beauty. When you learn how to manipulate a Robot Master in such a way that they sacrifice their upper hand…when you trick them into leaping into what would have been a stray shot…when you stun them in place…when you behave in such a way that they no longer how to respond…

It’s wonderful.

It’s truly, deeply wonderful. Because it requires you to respect them as adversaries. It requires you to learn to think as they do. It requires you to figure them out, and to identify hidden chinks in their durable armor. They stop being a boss, and become instead a satisfying rival.

What’s more, their ultimate predictability and exploitability make sense within the games’ universe: these are robots. They are programmed. They behave in certain ways. Some of them have better AI than others, but they’re all defined by a sequence of code. That’s because they’re video game enemies, yes, but it’s also because they’re robots built and programmed by scientists within the game. When you outwit a Robot Master, you’re also outwitting his designer. You’re playing a game of violent chess.

Bomb Man, for instance, is programmed to flee you, which is only something you’d discover if you keep trying to run right into him. Keep the distance between the two of you narrow enough and he’ll keep hopping around, helplessly open to your shots. The fact that this hinges upon counterintuitive behavior (contact damage hurts you, and you have a long-range weapon) helps it to function as a quiet puzzle in the background of the fight…one you may not even realize is there to be solved.

And he’s not the only one. Crash Man is programmed to jump and fire whenever you shoot, which means if you’re already in the air when you do so he can leap into your projectile and miss you with his. Heat Man will go into a strictly defensive mode whenever he is hit, which means you can prevent him from attacking at all (barring his initial volley) if you’re quick enough on the trigger. If you hit Elec Man with a Buster shot every time he raises his arms, he’ll never attack you. All of these are puzzles that encourage players to experiment and reward careful attention.

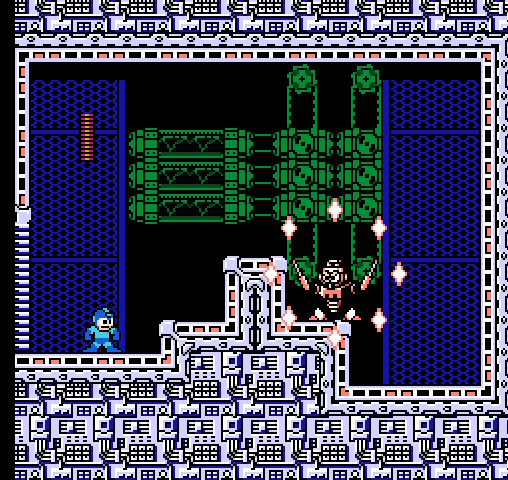

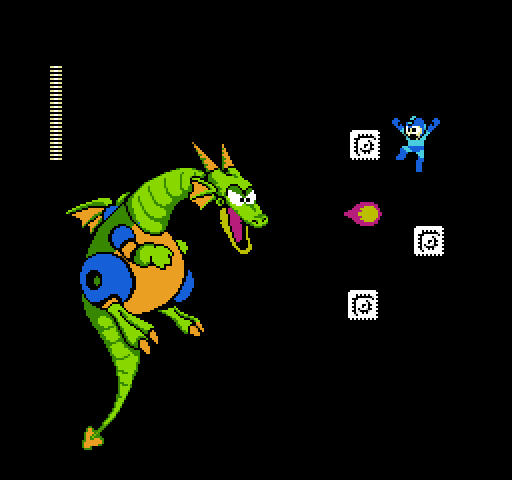

(Short digression: this illustrates another reason I don’t particularly enjoy the Dr. Wily stages. While those bosses tend to be bigger and more technically impressive, there’s little grace to them. They’re nearly all just big, powerful bullies. Their battles aren’t balletic; they’re a gradual chipping away at walls.)

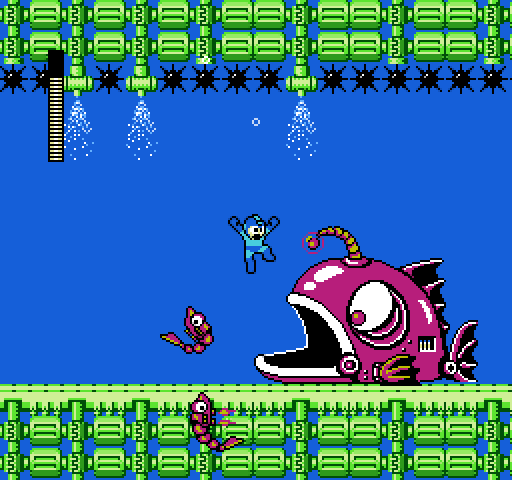

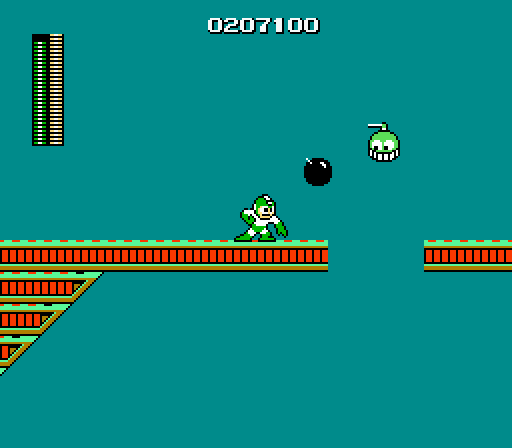

Mega Man 3‘s bosses overall don’t feel as satisfying to me as many of the earlier (and later) Robot Masters. They’re not terrible, exactly…they just feel less…designed. I don’t get the same satisfying sense of unraveling behavioral code here that I get from the other games.

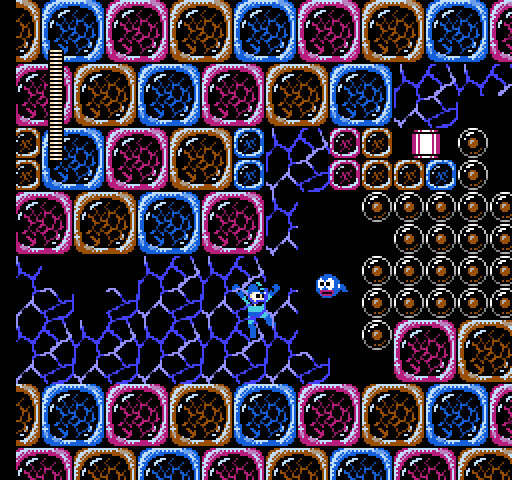

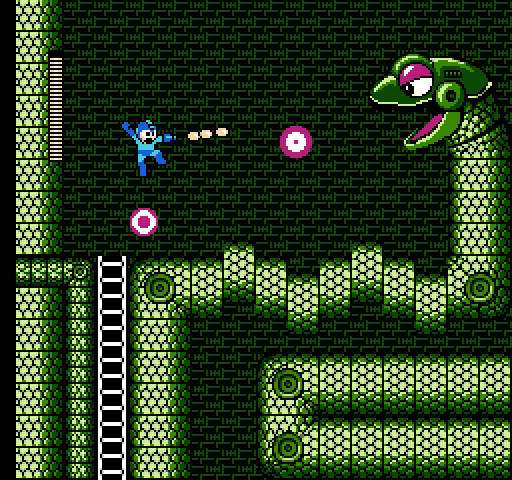

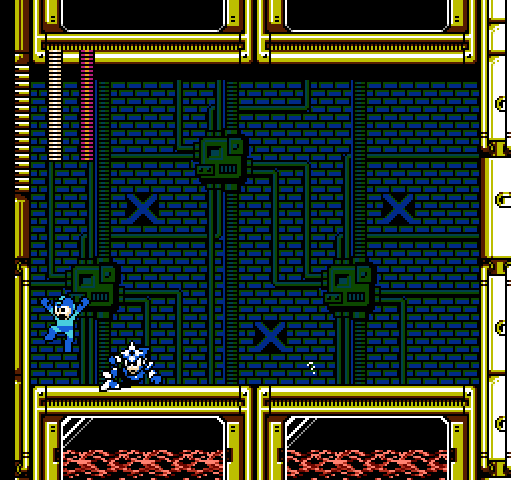

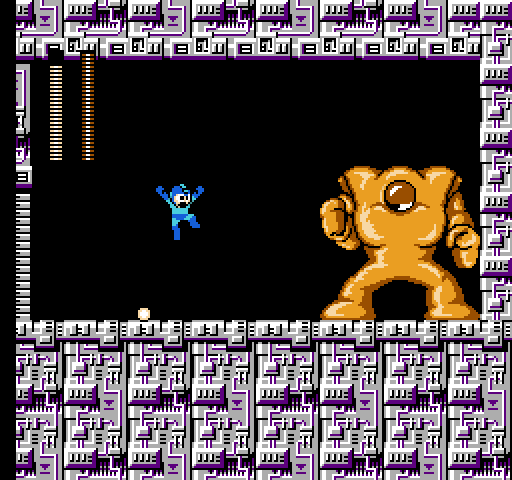

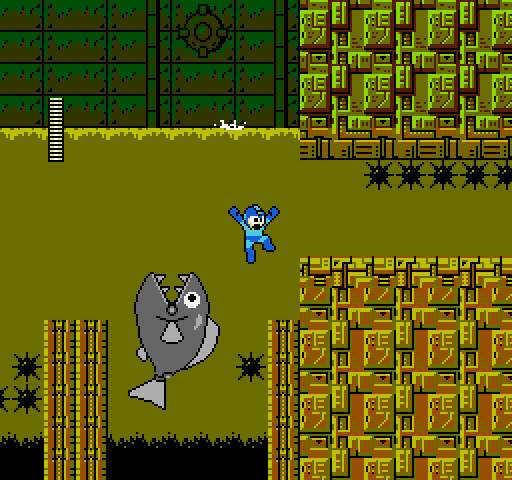

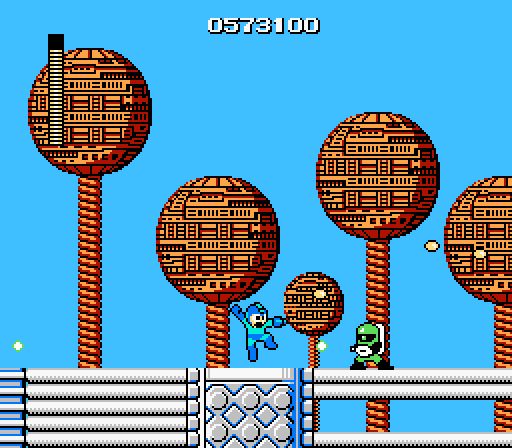

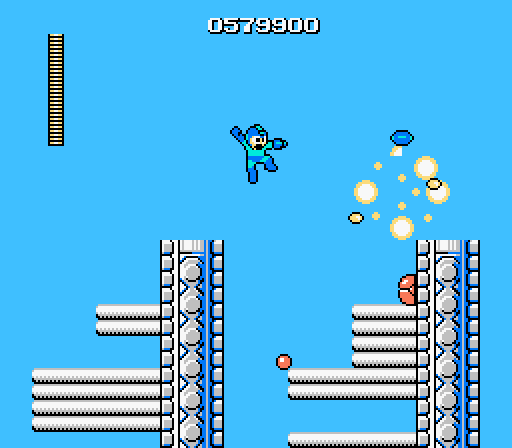

Gemini Man is a welcome and glorious exception to the rule, as his fight is actually an interesting one. Not only does it consist of two bosses, but it has two phases, really pushing the Gemini angle in exactly the right way. (The stage has nothing to do with the theme, so the boss fight might as well go nuts with it.)

In the first phase, Gemini Men are programmed to circle the room and collide with you, but they also stop and return fire whenever you shoot at them. This either means that you need to fire when they’re both in the air and can’t attack or that you need to be already leaping their projectile before they shoot it. Then, in the second phase, there’s only one Gemini Man, and this one jumps when you shoot at him. That’s both important to know in order to actually hit him, and your best method of avoiding him as he paces around: shoot and then quickly slide underneath.

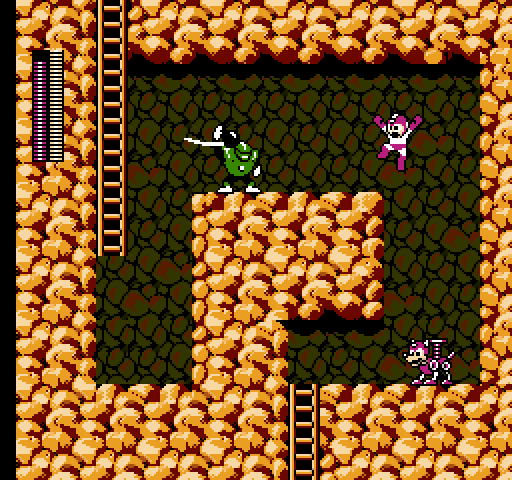

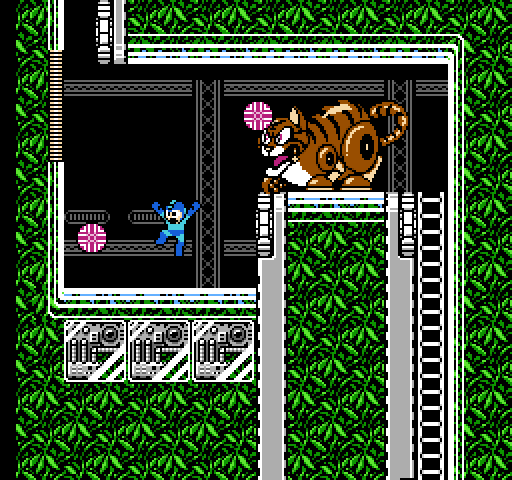

It’s a great boss fight, but it’s almost the only one. Snake Man and Magnet Man both go back and forth across the screen, firing at standard intervals. Spark Man does the same, firing at non-standard intervals. Hard Man fires, jumps, fires, jumps. Needle Man and Shadow Man just go haywire, jumping and firing at rates too quick for any reasonable player to comprehend. Top Man is an idiot.

So many great Robot Master concepts, but so little thought went into their execution. They don’t feel reactive in the way that Gemini Man and other great Robot Masters do. Rather, it feels like you have no impact at all, and they’d be going through the same routines, unchanged, even if you never showed up at their doors. That’s simply not satisfying.

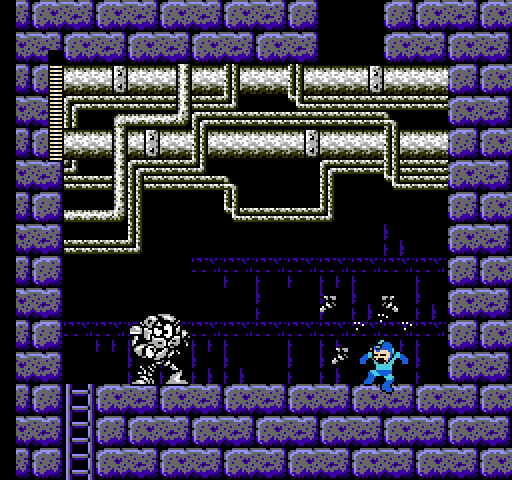

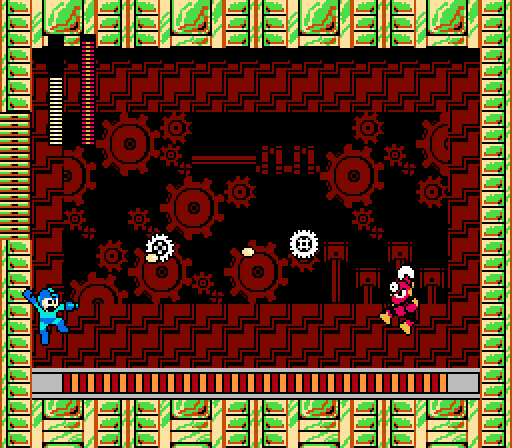

That’s not the only problem with the boss fights, though: there’s also lag.

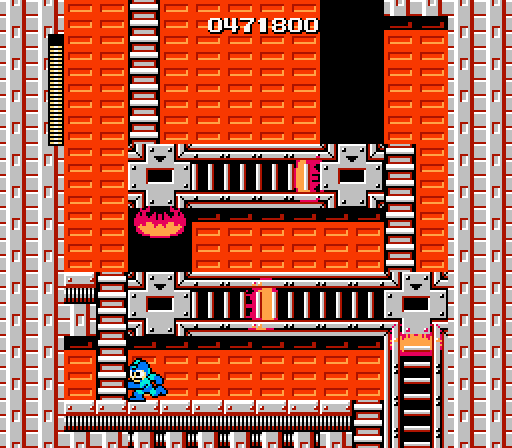

Mega Man 3 lags constantly, for no clear reason. Fights with Spark Man, Gemini Man, and Snake Man all slow the game to a crawl…and there’s nothing else happening. The least Mega Man 3 should be able to do is process its showcase duels without falling apart, but it can’t. It even struggles with minibosses, such as the cats in Top Man’s stage. It’s one thing if the player allows too many enemies to follow him into a taxing area, but in these cases it doesn’t take more than a boss showing up for the game to sputter and choke.

And we’ve already spoken about the Gemini Laser; just using it seems to cripple the game, which indicates that the lag is a coding issue. Mega Man 3 is full of things that just don’t work properly.

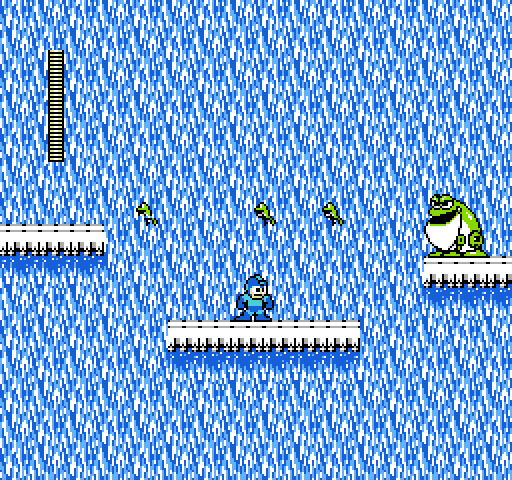

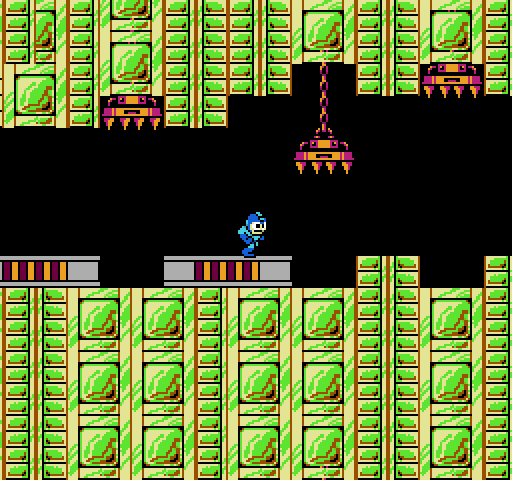

Not to mention the fact that the aesthetics of the Robot Master levels aren’t as naturally themed as they previously were. Sure, Snake Man makes up a lot of the deficit, as he’s a snake who shoots smaller snakes that crawl around a room made of snakes in a level made of other snakes, but Hard Man is just…in a gorge. Top Man is in some kind of plant nursery, I guess. And Needle Man is an angry plum on a pirate ship? I have no idea, and the lack of care doesn’t end there.

There are the off-center hitboxes, particularly Shadow Man’s and Gemini Man’s. There are the Junk Golem enemies that continue to attack after they’re dead. There are the cloud platforms in Snake Man’s stage that will glitch you into a bottomless pit. And the best thing I can say about the Wily stages is that the Yellow Devil’s new breasts are incredible.

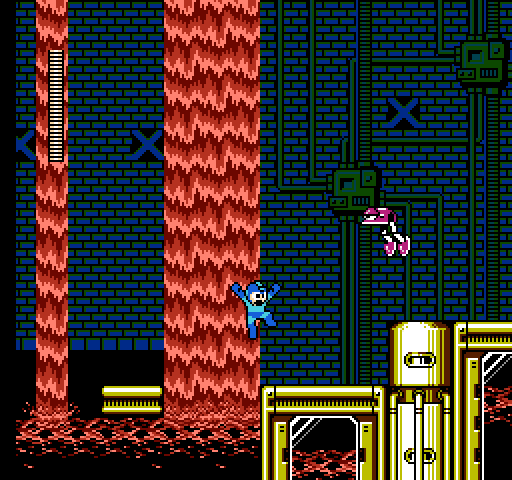

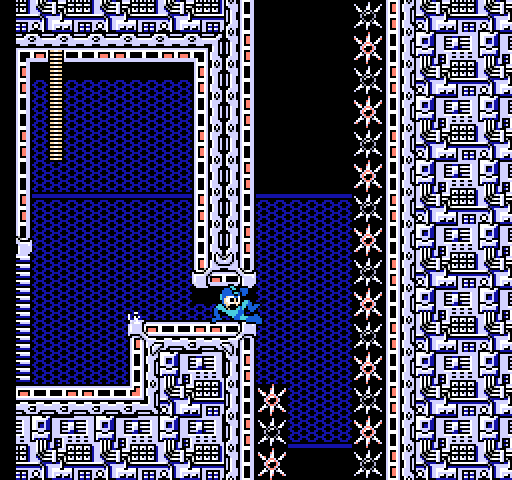

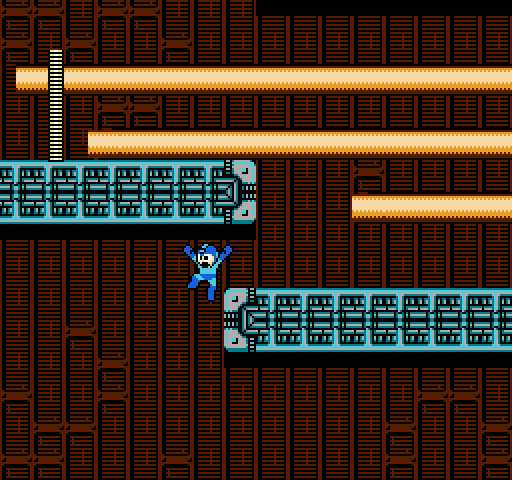

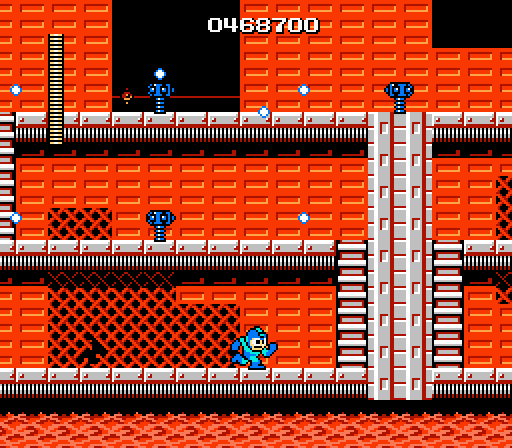

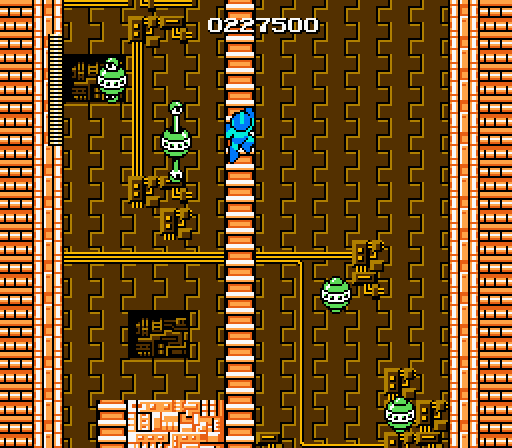

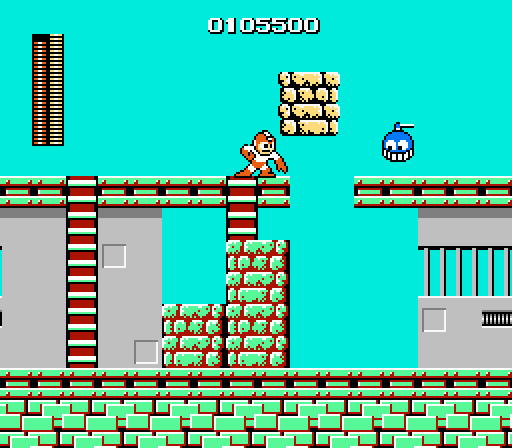

Then there’s the Doc Robot stages…remixed versions of four earlier stages with new hazards and layouts, featuring spiritual rematches with Robot Masters from Mega Man 2. It’s a great concept that, to put it honestly, is absolutely terrible in execution.

The stages don’t feel fair or interesting, functioning more as tedious gauntlets with oddly-chosen checkpoints than actual tests of anything we’ve learned as players. The fact that it’s possible to get stuck with no way to progress or die if you run out of energy for utilities, requiring a full reset of the console, makes me suspicious of just how much these stages were even playtested.

Mega Man 3 just feels a bit…careless.

It has great ideas. It really does.

And I want to love it.

I want to love Mega Man 3.

I want to play it and love it and shout from the rooftops about how great it is.

But I can’t.

Because as much as it introduced, it also regressed to feeling raw and experimental rather than tight and rewarding.

It gave us great characters and more great music.

But its Robot Masters don’t behave in interesting ways. Its weapons aren’t worth using. Its stages range from uninspired to careless. It’s glitchy. It’s unfair. It’s mindlessly punishing and yet too easy, providing few examples of genuinely fair challenges but also throwing so many extra lives and E-tanks at you that it feels impossible to lose. (I ended my game with 20 and 9 respectively when I replayed it for this review, and I was not playing carefully at all.)

I want to love Mega Man 3.

I do.

But maybe it tried to do a bit too much. Just like Mega Man.

And, as with Mega Man, it took the next game to show us how to do it right.

Best Robot Master: Gemini Man

Best Stage: Gemini Man

Best Weapon: Shadow Blade

Best Theme: Gemini Man

Overall Ranking: 2 > 3 > 1

(All screenshots courtesy of the excellent Mega Man Network.)