When it comes to sincere and affecting meditations on the human condition, Monty Python will probably not be the first thing that comes to mind. And yet the globally-popular sketch comedy troupe made a name for themselves with material about God, about philosophy, about death, about inner conflict, about melancholy, about fear, about desperation, about alienation, and about pretty much anything else you could imagine.

Those skits, produced mainly for their television program Monty Python’s Flying Circus (though also performed in other media, such as comedy albums and live performances), are more popularly remembered for their clever wordplay and unrivaled physical comedy than they are as any profound explorations of their subjects, but there’s something intrinsically human about the Monty Python canon. After all, that wordplay wouldn’t be as funny if society wasn’t already so confusing, and that physical comedy wouldn’t resonate if we weren’t already conditioned to accept the absurdity of our own daily interactions.

When Terry Jones fails to get medical assistance from Dr. Graham Chapman because he’s bleeding out too quickly to fill out the patient admission forms, there’s a recognizable undercurrent. It’s exaggerated, certainly, but it’s recognizable. When John Cleese performs all manner of silly walks it’s funny…but also forces us to wonder why they are funny, when — we’re led to believe — our own walks, and gestures, and handshakes, and ladder climbing, and dancing, and anything else we do with our bodies are not. Are we just conditioned to accept certain kinds of absurdities as given? Why are Cleese’s silly walks any different? Again, they’re exaggerated, but how much do they need to be exaggerated before we find them funny? Where’s the line between what we do and what we laugh at other people for doing?

The Pythons were always capable of injecting genuine insight into their work, even if they rarely or never chose to openly explore it. Life of Brian would certainly qualify as one of their baldest statements, and it’s also one of their most powerful and best. But what of The Meaning of Life? Comparatively less loved — but no less brilliant — The Meaning of Life seems to arrive with a huge announcement of cosmic philosophizing, putters around in circles for a bit, and then completely runs out of steam.

At least, that’s what it does in one sense. Its aimlessness and lack of drive are part of the joke in a film called The Meaning of Life, but is that all there is to it? Or is there some real, deeper message disguised by its carefully calculated sense of chaos?

The Meaning of Life is Monty Python’s third and final film of original material, and it stands apart from the other two in very obvious ways. First of all, there is no driving plot to the film, and no central character that we can follow from beginning to end. To further the sense of narrative disorientation, it does not even unfold chronologically.

In fact, it’s all too tempting to dismiss the film as being nothing more than a collection of sketches, linked together by some sort of vague insinuation of a common theme. And, to be fair, that’s an understandable perspective for somebody to have. It’s not, however, the final word, because The Meaning of Life does manage to blossom into something more than a string of barely-related comedy skits. It may not bother with a singular, chief narrative and there may not be an Arthur or a Brian with whom we can align ourselves for the ride, but it does open with a question (“I mean, what’s it all about?”), offers a promise that the question will be answered (“For a change, it will all be made clear”), and closes with appropriate fulfillment of that promise (“Thank you, Brigitte”).

In fact, it’s all too tempting to dismiss the film as being nothing more than a collection of sketches, linked together by some sort of vague insinuation of a common theme. And, to be fair, that’s an understandable perspective for somebody to have. It’s not, however, the final word, because The Meaning of Life does manage to blossom into something more than a string of barely-related comedy skits. It may not bother with a singular, chief narrative and there may not be an Arthur or a Brian with whom we can align ourselves for the ride, but it does open with a question (“I mean, what’s it all about?”), offers a promise that the question will be answered (“For a change, it will all be made clear”), and closes with appropriate fulfillment of that promise (“Thank you, Brigitte”).

The question of The Meaning of Life, posed in the film’s first scene, is resolved just before the film ends. And yet the meaning given at The End of the Film carries no more weight than the other brief ponderances peppered throughout the script, and it only appears to be more important because of its structural placement as concluding sentiment. Here it is in its entirety:

Well, it’s nothing special: try to be nice to people, avoid eating fat, read a good book every now and then, get some walking in and try to live together in peace and harmony with people of all creeds and nations.

Feeling a little dissatisfied with life’s ultimate meaning? You should be. It’s one of the major jokes of the film, after all, and if you are somehow satisfied with what is more an impersonal, itemized list of basic social advice than any kind of real, underlying meaning of existence, well, then the Pythons probably can’t help you.

But let’s not get bogged down in that, because not only is this “Meaning of Life” disappointing…it’s not even the Meaning of Life that the film itself suggests! Nothing in The Meaning of Life suggests that being nice to people will get you anywhere, nor is reading a good book ever suggested to do you much good (though it does get one character out of marching up and down the square). Getting some walking in and avoiding fat might make you less likely to become Mr. Creosote, and living in harmony would have avoided some otherwise pointless death in the war sequences, but, again, even if these items qualify as good advice they don’t actually clarify the mystery of existence. The Meaning of Life explicitly stated by The Meaning of Life therefore isn’t likely to be The Meaning of Life that The Meaning of Life actually believes to be true.

Also, consider the source. Is the female presenter a reliable vessel through which the answers to the grandest of grand questions might be delivered? Certainly not, as, immediately following her delivery of life’s meaning, she lapses into a self-righteous tirade against cinema, censors and the movie-going public in general. (That’s you.) Generally speaking it is never a good idea to take as gospel the proclamations of a character with an obvious agenda, and agendas don’t get any more obvious than hers. As if that were not enough, she then promises “completely gratuitous pictures of penises,” which never do come. (Ahem.) So not only is she biased, but she is also unreliable. If she is not even an authority on the contents of her own film, how could we expect her to understand the workings of the infinite cosmos?

We can’t. So, fine, that much is clear, and the film’s stated Meaning is bunk.

But that, then, should raise a further question: does Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life actually have an answer better than what we are given at the end?

Personally, I believe it does…it’s simply a question — like the fish in the middle of the film — of where.

Skipping The Crimson Permanent Assurance (for the time being), we find ourselves gazing into an empty fish tank…or so we think. First one fish, and then another, and then another four, swim into view, greeting each other and exchanging bland pleasantries.

We should be reminded here of a far more human interaction, such as arriving at the office for another day of work, or perhaps stilted, unenthusiastic talk over breakfast. We are only a few seconds into the film, and already we are presented with a tankful of fish in a scaled-down approximation of human interaction. A glass-tank microcosm, if you will. And, just in case someone out there might not have understood the parallel, each fish has a real, human face.

We are meant to see the fish tank segments as one of the most important segments in the film, based on the important fact that it recurs several times, whereas nearly every other segment is closed off and abandoned one by one, having served its singular purpose.

We are meant to see the fish tank segments as one of the most important segments in the film, based on the important fact that it recurs several times, whereas nearly every other segment is closed off and abandoned one by one, having served its singular purpose.

But why fish? If, to backtrack for a moment, we opened with several adult males in an office, standing around the water cooler, greeting each other and eventually pondering the meaning of existence, wouldn’t that be enough to get the film rolling?

The answer is yes, absolutely, but there are two reasons this would not work. Firstly it wouldn’t be as funny, and it wouldn’t be nearly as striking a visual upon which to open the film. And, secondly, it would actually start our journey on an uncomfortably sombre note. These fish, after all, only begin to question the nature of existence when death is introduced among their number: they stare helplessly through the glass as Howard — who was among them as recently as the night before — is presented by a waiter, dead and grilled on a platter. It is here, at this precise moment, that the meaing of life itself is raised…that they take the world outside of their small tank into consideration…and that they begin to question the nature of a universe that could allow such a thing to cruelly — and, to them, mysteriously — happen in what they had once believed to be a safe environment.

Even if the entire film to follow were played out just as we know it, there’s no question that the human equivalent of the same opening would start the film sourly, and could actually make much of what follows appear to be in poor taste. By opening with the bathetic fish, the Pythons manage to construct a morbid comic conceit that managed not to feel particularly dark, and that’s what sets the tone for what is to follow: enormous ideas explored in small — and resonatingly irrelevant — ways.

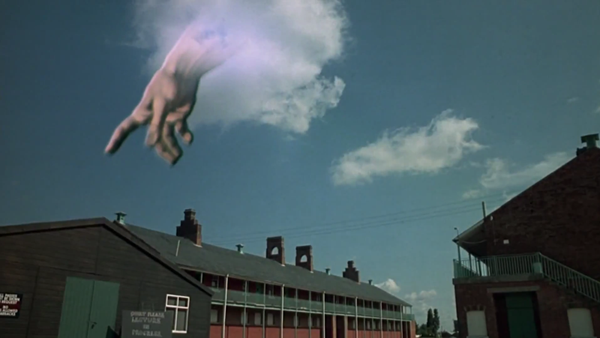

Consider the film’s opening theme song that follows. In addition to being supported by possibly the best piece of animation Terry Gilliam ever created for the group, the title song serves as an important overture to the film, and also a catchy sort of mission statement on behalf of the troupe.

While it is impossible for a first-time viewer to know this so early in the film, music plays a much greater and more important role in The Meaning of Life than anywhere else in the Python universe, and here, already, we are being promised through song that the questions posed by the fish will not go unanswered.

“Come along,” it seems to say, and it’s not entirely coincidental that Eric Idle performs the song with the same French accent he will later use in his portrayal of Gaston the waiter. Both the singer and the waiter (who may be the same person) invite us to follow them on a journey that will eventually reveal to us the meaning of existence.

Rather than shape the film in any way that implies direct movement toward one grand solution (or, to put it another way, a film that gradually narrows from confusion toward enlightenment), though, the Pythons give us a selection of metaphorical and indirect musings on the general nature of existence. Sometimes we seem to drift very close to an answer (“You know, Maria, I sometimes wonder whether we’ll ever discover the meaning of it all working in a place like this…”) and sometimes we seem to be helplessly off course (Tiger Brand Coffee is a real treat / even tigers prefer a cup of it to real meat!), but it is precisely this seemingly-carefree patterning that allows the film to work. After all, if the zanier, irrelevant situations were all bunched up together toward the beginning of the film and the comparatively serious, verbose musings on the strangeness of existence were strung together at the end, The Meaning of LifE would be a plodding (and didactic) fizzle. Instead, the cycles of life are emphasized, which serves both the pacing and relatability of the film.

Triumph and tragedy alternate throughout the film, yet there is always a steady magnetic return to the middle ground of life’s tedium and banality, such as when trench warfare takes a back seat to a birthday celebration, or an exploding restaurant patron gives way to an after-hours cigarette break. Whenever big ideas are touched upon, all of the characters — except for the fish, who seem to genuinely crave an answer more than anyone else in the film does — tend to blithely shrug them off in favor of getting on with their lives. The elderly Hendys illustrate this most vividly (“Waiter? This conversation isn’t very good…”), but examples of this very human tendency to shy away from dangerous questions can be found everywhere. As silly as The Meaning of Life gets, and it certainly does get silly, there is always a deliberate element of human befuddlement that keeps it grounded.

The film, however, is called The Meaning of Life, not The Meaning of Human Life, and the Pythons have fun with this. We take several forays into the Kingdoms Animal (the fish) and Vegetable (the dying autumn leaves). In each instance, though, and interestingly enough a human veneer is applied: the fish are quietly content with their lives until tragedy spurs them to question larger things, and the leaves are affected — in ever-increasing number — by the grief of having lost somebody close to them.

The film, however, is called The Meaning of Life, not The Meaning of Human Life, and the Pythons have fun with this. We take several forays into the Kingdoms Animal (the fish) and Vegetable (the dying autumn leaves). In each instance, though, and interestingly enough a human veneer is applied: the fish are quietly content with their lives until tragedy spurs them to question larger things, and the leaves are affected — in ever-increasing number — by the grief of having lost somebody close to them.

In fact, taken together, these two situations demonstrate opposite reactions to an identical stimulus: one constructive, the other destructive. Faced with the reality — and inevitability — of death, the fish choose to ponder life, and they are rewarded for this philosophizing by a film that promises an answer to their questions. The leaves, on the other hand, when faced with the same tragedy, turn instead to the conclusion that life is inescapably cruel, and the cynicism leads quite directly to suicide. The fish see death as an excuse to explore life’s mystery, and the leaves treat death as a reason to stop trying. The fish bring the entire film to life, and the only thing the leaves bring to life is the Grim Reaper — channeled by their negative reaction to existence’s only real assurance — who then brings the lives of several more characters (and the “life” of the film itself) to a close.

Duality of this type exists all throughout the film. We are given two different versions of the process of birth, two different live-action scenes of death, two different wars, two appearances of The Crimson Permanent Assurance, two helpings of “The Galaxy Song” (more on that later), and so on. We are invited, routinely, to compare and contrast the various choices made throughout the film.

In fact, the second of the birth segments (Birth in the Third World) also has another, internal dichotomy for us to explore: the Protestant family unit versus the Catholic family unit. The differences between the families are strikingly obvious, but they each exist in both a positive and negative sense, so that there is no clear “right” answer suggested by the film. For instance, the Catholic family lives in squalor and must sell its children for medical experimentation in order to make ends meet…by contrast, the Protestants appear to be well-to-do and cozy in their home life, yet their interactions are impersonal and entirely without emotion.

Additionally, the patriarch of each family demonstrates severe sexual selfishness, though in opposite directions. The Catholic man may indeed be guided by his religious faith when he refuses to use contraceptive devices, but the enormous (and increasing) number of his children proves that he hasn’t taken any steps to keep his libido in check. Conversely (but in definite complement) the Protestant man withholds sexual intercourse from his wife, who would clearly benefit from receiving attention in that very way. The Catholic keeps on his selfishly sexual path without regard to the consequences his family will face, and the Protestant keeps on his selfishly non-sexual path despite the consequenced hiw wife will face. Python has managed to caution us against two very unenviable extremes, and it is suggested that the “right” answer is actually somewhere in the unspoken middle ground.

In fact, this seems to be a good rule for interpreting the film itself: we are shown extremes, but the Meaning of Life, if we are to find it at all, is going to be somewhere inside, unemphasized, perhaps even silent. But, it is there. Just as darkness cannot exist without light, these moments of clear wrongness cannot exist without at least a suggestion of the “right” way to do things.

Another perhaps important duality can be found by comparing the Catholic and Protestant couples discussing birth at the beginning of the film to the couples confronted by Death at the end. Whereas the religious couples each have an unflinching faith in something larger, the three couples at the end of the film refuse to believe in anything larger than themselves, even when they are confronted by a physical manifestation of the Spiritual World. In fact, they cling to every last material vestige that they can, even as they’re dragged into the afterlife, taking their drinks and automobiles along with them.

Again, neither of these viewpoints is explicitly endorsed by the film itself; the audience is always meant to be laughing at these characters, whatever opposing things they believe, rather than aligning themselves with them. The “right” answer, again, must be somewhere in the middle. All of which, of course, is at odds with the fact that the female presenter claims to have a concise and inarguable moral for all of us to accept without question.

Part of the reason we, as viewers, might be tempted to accept her moral is that, thanks to The Middle of the Film and The End of the Film, this female presenter appears to be our framing device, and therefore exists on some narrative level “above” the rest of the characters. That is to say that she is speaking to us watching the film directly and could — should such a need arise — summarize the action of any other segment of them, while conversely no other character in the film would be in a position to summarize her segments.

This is reinforced by the fact that “Christmas in Heaven” is cut short when the television we are watching is switched off, and the camera turns to reintroduce the presenter, along with the suggestion that she has been watching along with us.

But why? What good did it do Python to set such an unreliable character up to serve as our personified framing device? Well, the Middle / End of the Film segments form a flimsy frame at best. It is only suggested that these segments exist on some level above the rest of the film…it is not confirmed. In fact, I would argue that the opposite is confirmed, and that these segments should not be viewed as having any more importance than the others.

After all, The Meaning of Life seems to have been generated spontaneously — the cinematic equivalent of a Big Bang, if you will — simply because the fish raised an interesting question. The film itself is serving as a sort of elaborate and indirect answer to that question, with the female presenter appearing to have a broader vantage point than any other character in the film. In reality, however, she appears only twice, and serves as a red herring (natch) each time.

In the Middle of the Film we play a game of Find the Fish. Where is the fish? Well…it’s probably nowhere, but the most fair thing we can say about it is that we don’t know where it is. We are given cryptic clues as to its whereabouts, bizarre characters strut around either in order to distract us from the search or to help us along, and various possibilities are shouted out from the film’s “audience.” An interestingly complicated — and ultimately unwinnable — arrangement for such a trifling question…yet at the End of the Film the supposed ultimate solution to life’s true meaning is found…in an envelope that is conveniently handed to the presenter from off camera.

In the Middle of the Film we play a game of Find the Fish. Where is the fish? Well…it’s probably nowhere, but the most fair thing we can say about it is that we don’t know where it is. We are given cryptic clues as to its whereabouts, bizarre characters strut around either in order to distract us from the search or to help us along, and various possibilities are shouted out from the film’s “audience.” An interestingly complicated — and ultimately unwinnable — arrangement for such a trifling question…yet at the End of the Film the supposed ultimate solution to life’s true meaning is found…in an envelope that is conveniently handed to the presenter from off camera.

The unbalance seems almost criminal; the search for the fish is more elaborate and difficult than the search for the Meaning of Life. One requires, it seems, an impossible amount of effort and meditation, and the other is simple produced on command. Something isn’t right here. Something is — forgive this — fishy.

It’s important that we keep the Middle of the Film in mind when we watch the End of the Film, as it reminds us that nothing important in this film could be located and explained so easily. In fact, the game of Find the Fish should serve as a thematic explanation of the film on a much smaller scale: humorous wordplay, bizarre characters, an impossible search — isn’t this practically the Monty Python mantra? Find the Fish is a cautionary tale to the viewer, you should keep it in mind as you watch the film. If there is a fish to be found, its location (and identity) will not be explicitly revealed. You are provided with your clues and a little entertainment in the process, and then you are shoved politely along to the next segment, never knowing if it was right under your nose…and you missed it.

So what is the film’s framing device? If the Middle / End of the Film segments are just unhelpful distractions rather than any kind of useful guidance, is there any segment of the film that stands above the others in terms of authority?

The answer is yes. The fish. The fish in the tank not only start off the film, but they appear to be “above” the Middle of the Film as well, as they are able to watch and comment on it when it’s over. Which is somewhat problematic, because it shuffles our levels of authority around a bit, but it’s not wholly unresolvable.

For starters, we have a lowest level of the film, in which the characters do not know they’re characters and do not realize they are in a film. Above them is the Middle / End of the Film lady, who is aware that she is in a film and that she is presenting segments of it. Above her are the fish, as they are able to watch and comment upon what she says and does. This means that the fish are at least two levels above the main action of the film itself, yet when Mr. Creosote enters the restaurant the fish all panic and scatter, meaning that, somehow, the film had managed to overtake itself. We no longer have three parallel levels of reality within the film — instead, somehow, unpredictably, the lines have converged, and the fish, previously in some authoritative position, are now potentially in danger from the action on the lowest fictional plane of events.

In fact, it’s more than a little likely that Creosote ate them all. For all they wanted to know about the Meaning of Life, and as many times as they interrupted the film prior to that point to wonder when we’d finally hear something about it, the fish make no interruption whatsoever when we actually encounter a segment entitled The Meaning of Life, simply because they are no longer around to comment.

They were destroyed by events that should have been two levels safely below them. Somewhere along the way the film got tangled and the planes began to cross and intersect. The film — quite literally — consumed its own framing device. Oh, look. Howard’s been eaten.

Some more glaring evidence of this self-consumptive tangle occurs when The Crimson Permanent Assurance escapes the confines of its “supporting feature” status and attacks the main picture, only to have its setting and characters destroyed in a contrary manner to the destruction we’d witnessed earlier in the film. And, finally, instead of the gratuitous pictures of penises we are promised by the presenter, we have, instead, a lonesome television set floating through space, playing — of all the metaphorical possibilities — the opening animation to Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

The film, at this point, has escaped every one of its boundaries. It has destroyed the fish who set it into motion in the first place, it has overturned the authority of the woman in its framing devices, and it has crushed its supporting feature. It has become an entity unto itself, drifting alone through the inhuman coldness of space, with nobody to answer to, and our control over our experience of the film is also symbolically pulled away, as the television drifts further and further from reach.

The film wrests control from us because it has one final thing to say, one concluding thought with which to leave us, and it begins that thought that begins with two sage words: “Just remember…”

“The Galaxy Song” closes the film, but before we discuss why that might be significant, we should wind back the clock a bit and consider its first appearance in the film, during the segment on Live Organ Transplants.

The song is an atypical one for Python, as there aren’t really any jokes in it, nor does it make use of clever phrasing or poke fun at a certain musical genre or social attitude. Furthermore, the song says practically nothing about the character who is singing it, as we’ve never seen him before and will never see him again. The song exists outside of the film’s other music numbers, outside of the character who is performing it, and very possibly outside of the film itself…a larger, vaster statement that halts the progress of the comedy sketch within which it’s embedded for three minutes or so, and then sends it spinning off in another direction.

The song is an atypical one for Python, as there aren’t really any jokes in it, nor does it make use of clever phrasing or poke fun at a certain musical genre or social attitude. Furthermore, the song says practically nothing about the character who is singing it, as we’ve never seen him before and will never see him again. The song exists outside of the film’s other music numbers, outside of the character who is performing it, and very possibly outside of the film itself…a larger, vaster statement that halts the progress of the comedy sketch within which it’s embedded for three minutes or so, and then sends it spinning off in another direction.

Every effort seems to be made to get us to pay attention to this song. The action of the live organ transplant comes to a halt and the set collapses around the characters. Our vocalist in pink escorts us into an empty starfield and…that’s it. There is now nothing at all to distract us from the song and its lyrics. There is a brilliant piece of Gilliam animation in this sequence, but it is confined entirely to the instrumental verse, and makes no effort to divert our attention from the content of the song itself.

If you make allowances for estimation, the facts about the universe as presented in “The Galaxy Song” are actually pretty accurate (as far as facts like that can be said to be accurate), so what happened here? We’re watching a comedy film, after all, but nothing particularly funny is happening…yes, the song is lovely, but it doesn’t contain any jokes. We do get stung by a slight barb in the closing line, but that line is sung after the vocalist and Mrs. Brown return to the set. In other words, we’ve been physically relocated for the duration of the song, and the lone humorous sentiment at the end is a lyrical way of easing us into our return.

But why this detour in the first place? Well, it’s because Mrs. Brown has a decision to make: does she give her liver to the two not-doctors who are asking for it? Bear in mind that such a choice would unquestionably result in here death, and it seems like an easy choice to make. She declines. John Cleese’s kind-of-doctor then introduces her to the vocalist in pink as a sort of final flail in his argument, and, after hearing the song and being confronted with the facts and figures of such an enormous, complicated, expanding universe, Mrs. Brown agrees to have her liver taken out, and to be killed in the process.

Yet the song itself is not inherently nihilistic, is it? It does — as we see — present its listeners with a sort of a choice to become nihilistic, but that isn’t explicitly the viewpoint that the song itself endorses. In fact it seems to endorse almost nothing at all, except for its opening and closing sentiments:

Whenever life gets you down, Mrs. Brown

And things seem hard or tough

And people are stupid, obnoxious or daft

And you feel that you’ve had quite enough

Just remember…

It’s that “just remember” that’s key, because this is the advice that the vocalist in pink was sent here to give. He introduces his song by saying that he knows that you sometimes see life as cruel and unforgiving, and, in fact, he doesn’t disagree with you. But just remember that the universe itself is so much bigger, and that whatever we might encounter during the course of this painful, incomprehensible scramble we call life, it amounts to precisely nothing when gauged against the incomprehensible enormities around us.

And, just in case she might have forgotten, he ends by bringing the song right back to a personal perspective:

So remember when you’re feeling very small and insecure

How amazingly unlikely is your birth.

So far from nihilism is this particular sentiment that it actually declares Mrs. Brown’s value as an individual. He stresses her own cosmic impossibility, and yet, by sheer virtue of her existence, she beaten the unfathomable odds: she is alive. In a universe that is not interested in her existence and against infinite conditions that could have (and should have) aligned to keep her from even being born, she has triumphed. She has beaten greater odds than she herself can ever know.

Yet when faced with the hugeness of the universe around her, she becomes nihilistic, loses her faith in her own significance, and sacrifices herself to the cause of live organ transplants.

“The Galaxy Song” can be read in either of two ways: it is either a life-affirming promise that every life is miraculous simply because, mathematically, we shouldn’t have ever existed to begin with, or it is an assurance that nothing we accomplish can amount to anything on a universal scale. Mrs. Brown has chosen to fall into the latter camp. She was faced with both morals, and she made her choice.

And just as she has been escorted by the vocalist away from the film and into a starfield where she can ponder the meaning of his words without distraction, so are we at the end of the film. We are left alone with his song in the vast emptiness of space, and now the decision is ours to make. Do we come away from the film feeling insignificant, or proud to be an individual? Does the weight of the facts drag us down or buoy us up? Do we resign ourselves to death’s inevitability, or do we choose to live life to its fullest? The first time we encounter the song, the decision is Mrs. Brown’s to make. The second time, it’s ours.

Mr. Brown sacrificed himself because he was too full of good intentions to realize that he was signing his own life away. Mrs. Brown sacrifices herself because she no longer has any intentions left, despite the fact that she’d be leaving an orphaned teenage son behind. Somewhere in the middle, we are silently assured, is the “right” answer.

There is one sequence in the film, however, that does hew closely to providing explicit human guidance. Surprisingly enough, that sequence is Mr. Creosote’s.

The Mr. Creosote sequence seems at first to exist only for the purpose of sheer, vile repulsion, and it never really offers any form of relief; instead, it builds to one enormous (and only partially cathartic) explosion, which is bigger than what we’ve already seen but isn’t necessarily any more disgusting. In fact, it’s hard to produce anything shocking after a scene as that, and so the Pythons make a wise decision to segue into a secondary segment called…The Meaning of Life. This segment sees three of the characters from the Mr. Creosote sketch cleaning up the restaurant, and idly pontificating over the nature of life and existence. It’s a quiet segment and is strikingly dry in its execution, considering the infamously over-the-top scene that preceded it.

The Mr. Creosote sequence seems at first to exist only for the purpose of sheer, vile repulsion, and it never really offers any form of relief; instead, it builds to one enormous (and only partially cathartic) explosion, which is bigger than what we’ve already seen but isn’t necessarily any more disgusting. In fact, it’s hard to produce anything shocking after a scene as that, and so the Pythons make a wise decision to segue into a secondary segment called…The Meaning of Life. This segment sees three of the characters from the Mr. Creosote sketch cleaning up the restaurant, and idly pontificating over the nature of life and existence. It’s a quiet segment and is strikingly dry in its execution, considering the infamously over-the-top scene that preceded it.

In terms of pacing the film, however, this is necessary, and also a deft artistic move. Instead of trying to trump the manic energy of Creosote’s visit, they reset the energy level to zero. Characters pass the time on chairs in a quiet room, discussing the meaning of life barely above a conversational whisper. The only thing shocking about the scene is that it manages to follow the insanity of Mr. Creosote without seeming out of place.

We really shouldn’t move on, however, without discussing the significant of the Mr. Creosote scene itself. What purpose does it serve in the greater film? For starters, it somehow manages to feel like one of the bigger and more important events in the movie. The first World War, for example, is actually just the backdrop for a sketch about an inopportune birthday party. The birth sequences are trivialized first by the doctors and then later by the Protestant couple, and even the arrival of Death turns out to say more about gradual acceptance than it does about sudden change.

The big things are made small, and, in the case of Mr. Creosote, the small things are made big. This one solitary evening out for a very overweight man seems to be of paramount importance. Why? Because it contains, at its heart, the most explicit exploration of social themes in the entire film. And, yes, it goes a long way toward helping us figure out the Meaning of Life.

The Mr. Creosote scene illustrates very clearly a hierarchical social structure and pecking order, which, during the course of the sketch, is shaken up by the second-highest ranking individual on the ladder.

Let’s break it down: at the top of the ladder we have Mr. Creosote, whose every whim, however selfish, disgusting or bizarre, is catered to by those beneath him. Immediately below is the Maitre D, played by John Cleese. Below him are the other patrons of the restaurant, who presumably command service from the rest of the restaurant staff but are certainly beneath the Maitre D’s wish to cater to Mr. Creosote. Beneath the other patrons would be Gaston, played by Eric Idle, who is essentially at everybody’s beck and call, and beneath him is Maria, the cleaning woman, because even though Gaston is passively abused, he is never humiliated nearly as badly as she. And beneath her, we have the fish, who have absolutely no say in anything, including their own fates, and are very likely consumed at some point during the course of the sketch.

All throughout the Creosote scene we see the results of this particular power structure play out, and eventually become strained. Each character plays his or her part in the hierarchy without complaint, and it isn’t until the sketch draws to a close that we realize that the Maitre D might have something underhanded in mind after all, as he plies his insufferable customer with a wafer-thin mint. When Creosote refuses, the Maitre D resorts to inserting it forcibly into Creosote’s mouth.

Knowingly, the Maitre D dives behind a low wall to protect himself from the resultant explosion. It was an intentional act of gastronomical terrorism, and, as a result, the Maitre D has installed himself as the new head of the social order, which is reflected by his demeanor during the following scene, in which he smokes a self-congratulatory cigarette and converses confidently with members of his staff.

He has managed to seize command of his own destiny, however temporarily, by incapacitating the man above him, and there is a definite change in the character of the Maitre D from one scene to the next. He is more at ease with himself, and allows himself a more relaxed posture. He is, for once, his own man, in control of his life and — for the time being at least — in command of the film.

He uses this newfound authority to steer the film more closely toward its stated central theme, and it’s an opportunity for both Terry Jones, as the cleaning woman, and Eric Idle, as Gaston, to shine. Each of them are invited to share their philosophies, and each character (as well as actor) embraces this opportunity fully.

With Creosote removed from the top of the social structure and the fish removed from the bottom, the Maitre D and the cleaning woman represent the highest and lowest social orders coming together. And, when they do, we learn that there’s more to the cleaning woman than appearances might have suggested:

I’ve worked in worse places, philosophically speaking. […] I used to work in the Academie Francaise, but it didn’t do me any good at all. And I once worked in the library in the Prado in Madrid, but it didn’t teach me nothing, I recall. And the Library of Congress…you’d have thought would hold some key. But it didn’t. And neither did the Bodlein Library. In the British Museum I hoped to find some clue. I worked there from nine ’til six, read every volume through, but it didn’t teach me nothing about life’s mystery. I just kept getting older, and it got more difficult to see, until eventually my eyes went and my arthritis got bad. And so now I’m cleaning up in here.

All of which should lead us to feel sorry for her. After all, she made took every opportunity to better herself, and to come to some sort of grander enlightenment about the nature of the world around her, only to run out of life in the process, to feel her body running down. She took a job cleaning up after people like Mr. Creosote with nothing to show for her intellectual pursuits. And, yes, she may follow up her story with an ignorant comment, but from a Meaning of Life standpoint, the real criticism we should have with her is the fore-runner to that anti-Semitic rhyme:

I feel that life is a game. You sometimes win or lose.

And there is the reason that she is a cleaning woman. She allowed herself to accept failure as possibility in her life, and, therefore, she did not fight against it. She accepted failure, which, in this particular social structure, is tantamount to inviting it. The very fact that she expects to lose as often as she wins is what keeps her on the bottom of the social order while the Maitre D and Mr. Creosote, both self-assured men in their own right, seek opportunities to make it to the top.

Gaston reveals a similar fact about himself as well when he takes us on a pilgrimage to the house in which he was born:

You know, one day, my mother…she took me on her knee and she said to me, “Gaston, my son…the world is a beautiful place. You must go into it, and love everyone. Try to make everyone happy, and bring peace and contentment everywhere you go.” And so…I became a waiter.

Whereas the cleaning woman has resigned herself to the fact that she will sometimes lose, Gaston has resigned himself to the fact that he must always lose, if it means he can make somebody else happier in the process. He may or may not hold resentment toward his mother for providing him with an outlook destined to keep him out of the privileged classes, but he certainly does become defensive after sharing his philosophy with us, suggesting that it’s more a desire to follow his mother’s teachings than any kind of innate belief within himself. In this case, nurture has indeed triumphed over nature, and Gaston storms off toward the home — a symbol of his mother and her teachings — when he begins to feel that we might find fault with his philosophy.

Something else is revealed in this scene, however: you are the central character. Throughout this entire sequence the camera operates from a first-person perspective. Characters address you, apologize to you, invite you to follow them, and become frustrated with you. It is for your benefit that they are having these discussions, and they sincerely want you to benefit from them, becoming upset when you walk out of the restaurant, or frustrated when you don’t seem to have learned anything from the philosophies they share.

In fact, if we take this along with the Middle / End of the film lady, and the fish in the tank at the beginning — who make it a point to face us head-on, all six of them, when they pose the question that gets the whole machine running — we realize that this is all for our benefit. From beginning to end, we are the ones meant to learn from this film.

There is no central character that we can following along on this journey, because the journey is ours.

Suddenly the film has transformed into a series of brief parables, and it is up to us to interpret them. Chronology and consistency no longer seem lacking, because the film is a series of ordered vignettes with a common agenda. It doesn’t succeed or fail based on its narrative thrust, it succeeds or fails based on the reaction it manages to get from us.

We are the central character, and we have been all along. The journey through the film is a personal one, and it is up to us what we take from it, how we apply what we’ve learned, and, as we are left to drift ponderously along through space with “The Galaxy Song,” what we decide to do next, even if we can’t be sure where it will take us.

The Meaning of Life has tremendous fun with the choices we might make along the way, but it never wavers from the fact that death remains inevitable. We may go somewhere, and we may not…but we sure as Hell can’t stay here. The film may make many concessions toward fantasy, but absolving us of death and dying is not one of them.

In fact, the Death segment features two illustrations of death’s inevitability. The first is Arthur Jarrett, who illustrates — philosophically speaking — that we are all hurtling toward death, no matter how desirable it might be to turn around and cling to life. There is no escape. Jarrett is dead, and the horde of topless women go unloved. The second promise of death’s inevitability is the fact that all six dinner guests are taken by the Grim Reaper, despite the fact that one of them didn’t even eat the salmon mousse that was meant to have killed them. Regardless of the decisions one might make along the way, we all get taken in the end.

In fact, the Death segment features two illustrations of death’s inevitability. The first is Arthur Jarrett, who illustrates — philosophically speaking — that we are all hurtling toward death, no matter how desirable it might be to turn around and cling to life. There is no escape. Jarrett is dead, and the horde of topless women go unloved. The second promise of death’s inevitability is the fact that all six dinner guests are taken by the Grim Reaper, despite the fact that one of them didn’t even eat the salmon mousse that was meant to have killed them. Regardless of the decisions one might make along the way, we all get taken in the end.

We can’t escape death. We know that. The question is what, then, is to keep us from falling into Mrs. Brown’s nihilism and just…giving up?

That is answered by the destination that the characters all reach at the end of the film: the afterlife. Here it is revealed that, in death, we retain our personalities and appearances, so whatever accomplishments we might have made in life are not for naught. We all meet up together in some spiritual night club and find ourselves on the receiving end of eternal entertainments. It’s a comically metaphorical illustration of one unfunny, very real universal claim: we are building toward one final, complex singularity.

The fact that all of the characters from the film — and, presumably, all throughout human history — converge in one location suggests that they are being kept there for a reason. That reason could be the gradual resetting of the entire universe, which, as proponents of the Big Crunch theory will tell you, is not an entirely fictional concept. The souls may be kept here for however long until the singularity is achieved, and all of time, space and matter is redistributed again from the start.

Even the lyrics to “Christmas in Heaven” seem to suggest that the narrowing toward singularity is already underway. Consider how many opposing forces are brought together for the sake of one song: it is snowing, but it is warm. Everyone dresses in their best suits, but still go swimming. The Sound of Music and the Jaws films converge as opposing — but presumably complementary — examples of great films, with the former running twice an hour, suggesting that time is indeed undergoing some sort of cosmic compression as well.

“Christmas in Heaven” manages to be both about the spiritual and the material, and the song itself spans several genres — it begins as a simple Christmas song, but soon becomes a heavy-handed lounge number, closing out with aspects of hymn, pop, funk, and salsa, all in one brief singalong. And, of course, the angels wear Santa suits and gratuitously expose their breasts, so that’s the spiritual, the material and the sexual becoming one.

Life is an assortment of themes and ideas, many of which are touched upon by the film — though certainly not all of them. The Meaning of Life doesn’t intend to provide one final satisfactory answer, but it does provide the viewer with a lot of material for launching a legitimate philosophical search of his or her own.

Was that the intention of the Pythons?

No. Certainly not.

But it says an awful lot about the kinds of people they must be if they can set out to create an hour and a half of comedy sketches, and just so happen to provide their audience with the fuel for a lifelong quest of spiritual examination.

They just don’t write like that anymore.