So! Trilogy of Terror, a new series that I’ll do each October, in which I take an in-depth look at three related horror films in the run-up to Halloween. They could be films in the same series, films by the same director, films with a common theme, or any relationship, really.

I’m kicking it off this year with Edgar Wright’s Blood and Ice Cream Trilogy. (The Three Flavours Cornetto Trilogy, for non-Americans.)

While only Shaun of the Dead is rooted in outright horror, both Hot Fuzz and The World’s End have horror-specific elements among their defining traits, so I’d argue that they qualify as well. Especially since all three films can be easily linked together to form one grander (if not necessarily cohesive) statement…but that’s probably a discussion for later.

I was surprised the first time I watched Shaun of the Dead. I remember seeing advertisements for it and…not being interested, really. I was a big fan of British comedy, but I hadn’t yet seen Spaced (which laid the groundwork for this film) so I missed out on the excitement that I would have otherwise felt.

To me, it just looked silly. There’s nothing wrong with silly, but there’s nothing rare about it either. Dumb comedies were — and continue to be — in ready supply, especially here in America. Importing another felt unnecessary. Seeking it out specifically felt absurd.

But then friends started to recommend it, particularly once it arrived on DVD. I figured that meant it was decently funny. Later on another friend — an independent film-maker that I respect greatly — recommended it, and I realized that it might also be good.

That’s what I wasn’t prepared for…a genuinely good film underneath the gore and the silliness. Indeed, I’m sure that that’s what most viewers weren’t prepared for.

Great jokes are always welcome, but you expect to find those in a film that bills itself as a comedy. That’s where they belong. They’re why people turn to comedies in the first place.

But great acting, great directing, great film-making…those are less common. Shaun of the Dead gave us all of that instead of what could have been — and what I expected to be — some disposable bit of gory pap.

Watching it for the first time, I was impressed. 11 years later, I’m even more impressed. Shaun of the Dead is a nearly perfect movie in my estimation. It’s funny, it’s insightful, it’s well-made, and it’s confident. There are new layers and details that reveal themselves every time I watch it, and I’ve seen it at least a couple dozen times by now. Every element works, and they work so well that I’m still finding new intricacies a decade down the line.

But what is it? Is it a horror film? A romantic comedy? A parody? Yes, it is. And it’s a lot of other things, too.

Shaun of the Dead shouldn’t succeed the way it does. It really shouldn’t. It has too many things happening at once. It’s tonally all over the map. It mixes high social commentary with low slapstick and expects them both to land. It should be a mess.

But it knows that.

And that’s kind of the point.

The film, ostensibly, centers on an ill-equipped man attempting to lead a group of survivors through the zombie apocalypse. The film also happens to be about that man getting his relationships in order, sorting his life out, and finding his place in the world. They’re two plotlines that aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive, but for a comedy that’s a pretty daring blend, especially since neither plot seems especially tailored to humor.

Which is probably why Shaun of the Dead works so well. It’s a comedy, but not mindlessly so. It thinks its way through — and deeper into — its complications, because it has to. It sets itself an unenviable goal of spanning genres and delivering its impact on multiple fronts, so it had no choice but to be brainy about it. These things don’t just work together on their own; if they work, it’s because some group of artists worked together to make it work.

The film focuses on character and thematic resonance as though it were a drama. And while it has a slew of unforgettably funny moments, it’s also always — unfailingly — sincere. It’s a work of love, filled with respect and admiration for its source material, and an impressive ability to outdo itself, to keep layering, to dream up a great scene and then present it in some way that makes it better.

Which is what struck me the first time: the construction of the film. The way Shaun’s morning routine is urgently edited into a series of quick cuts, like an action montage. The way the sun rises on our passed-out hero like a floodlight snapping on. The way the aftermath of a fatal car wreck plays out in the background, behind an otherwise quiet scene of two friends reconnecting.

Wright doesn’t shoot the movie like a comedy. He shoots it like a horror film, a drama, an action movie, and like almost anything but a comedy. Which, obviously, makes it funnier.

There’s great humor to be found in someone who takes himself seriously while saying and doing ridiculous things. In Shaun of the Dead, that’s a role knowingly filled by the director himself.

What’s great about that, and why this movie has staying power, is the fact that it allows you, in the audience, to do things other than laugh.

Even great comedies sometimes suffer from the fact that there needs to be space between the jokes, but the ones that take themselves seriously — and allow themselves to be serious not in spite of but in addition to the jokes — have an opportunity to fill that space creatively.

That’s where characters explore their own dynamics. That’s where themes emerge and the echoing of lines and scene composition pays off. That’s where, to put it flatly, we’re allowed to care about what is happening.

And that’s the ace up Shaun of the Dead‘s sleeve: it makes its audience care.

It’s a great trick, and by no means an easy one to pull off. Reel them in with the promise of hilarious knockabout zombie gore, and break their hearts as two men find their friendship threatened by the responsibilities of adulthood.

It shouldn’t work, but it does…and it works because Wright and Pegg are in full command of their material. They know how they want the audience to react, and when, and they know exactly how to trigger it.

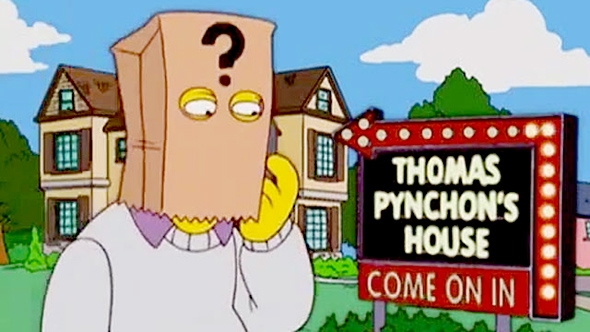

That’s why Spaced is a necessary part of this film’s pedigree. It goes deeper than seeing familiar faces and names plastered all over the film; it shares that show’s artistic DNA.

Wright directed Spaced in his own inimitable, inventive way, elevating a sitcom about two flatmates to levels of genuine visual art. And Pegg — who co-wrote and starred in both that show and this film — took a set of caricatures and allowed them to evolve into a group of rich human beings with a web of complex relationships between them.

Shaun of the Dead may have been born of one episode’s fantasy sequence (in which Pegg’s character fights back a group of zombies), but the show’s real echoes are felt throughout the presentation of the film, and the script behind it. It informs the film’s entire creative process, and its agenda.

It’s no surprise that the cast is padded out (in both major and minor parts) with Spaced alums; these are people who already knew what Wright and Pegg would need from them, and would have some idea of how the film would ultimately work. Which is good, because it would be pretty easy for an unfamiliar actor to read the scene in which the group bludgeons a zombie to death to the beat of Queen’s “Don’t Stop Me Now” and get the wrong idea about how to pitch his performance.

Wright and Pegg’s masterful character work flows throughout the Trilogy, with an emphasis less on change than on the process of discovering who you already are. There’s still a kind of growth — and an important kind of growth — at play in each of the three films, but these are mainly voyages of self-discovery.

When taken as a whole, the Trilogy doesn’t present a definitive “right” kind of person to be. That’s a convenient topic to discuss here, in the first film, as Shaun’s housemates foreshadow Pegg’s later roles, and provide a basic template for understanding them.

When we meet him, Shaun is caught in the middle between Ed and Pete, played by Nick Frost and Peter Serafinowicz respectively…both of whom are Spaced actors as well. Ed is slovenly, crude, and unapologetically aimless. He lacks all ambition and refuses to grow up. On the other hand, he’s there for Shaun when Liz breaks his heart, and does everything he can to hold his friend together. He’s loyal.

Pete, by contrast, is responsible and driven, interested in living a stable and secure life. He takes his career seriously and cares about the way he’s perceived. He’s also, however, humorless, and puts his own needs above other people’s feelings.

Pegg plays Shaun as being directly in the middle, frustrated with both of them, but envious of them as well. He tries to rise to his managerial duties at work and keep the survivors together later like Pete would, but he’s perfectly content to spend his life playing video games and hitting the pub with Ed.

Each of his housemates represents a possible direction for Shaun to take, but direction means commitment. And, as exemplified by his failing relationship with Liz, commitment is not one of Shaun’s strong points.

Instead of becoming more like either of them, he keeps to the middle path. He veers closer to neither Pete nor Ed; he remains Shaun. And while it seems a bit odd from a character-arc perspective that a man who opened the film in the undefined middle ground remains in the middle ground at the end, there’s still growth that has occurred: the middle ground is now defined. Shaun knows it, and understands it, and — most importantly — is comfortable with it.

He didn’t pull himself together and solve everything, but neither did he fall apart and lose everything. He’s not the kind of person who will — or can — do either. He’s the kind of person that can make it through an ordeal, but he’ll do so in neither triumph nor defeat.

There’s a reason he replies three times to Yvonne (Jessica Stevenson, another familiar Spaced face and that show’s co-writer) that he’s “surviving.” It’s a contextual joke within the film, but also a reminder of where Shaun is, and always will be: the middle. He’ll neither succeed nor fail; he’ll survive.

He exists in the band between the two extremes. When the film opens, it upsets and disappoints him that he can’t commit to either direction. By the end he still can’t commit, but he realizes that that’s okay. That’s who he is. And he’s comfortable with that.

We don’t see a different version of Shaun at the end of the film; we just see one that’s come to terms with who he already is.

Pegg plays the other two extremes in the films to follow. Nicholas Angel of Hot Fuzz is a humorless professional in the vein of Pete, and Gary King of The World’s End is an aimless eternal youth in Ed’s tradition.

Shaun of the Dead might see our hero staying just where he is, but the rest of the Trilogy explores the other possibilities. We get no definitive answer and all definitive answers, which is part of why the films function so well together.

Shaun of the Dead arrived at the front end of a resurgence of interest in zombies. While the image of the shambling corpse has been around for centuries, and was standardized back in 1968 by George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, zombies by and large had lost their cultural cachet.

Shaun of the Dead helped to usher in an undead renaissance that continues to this day. It arrived on the scene in essentially the same wave that brought us 28 Days Later (2002), Max Brooks’ The Zombie Survival Guide (2003), and the first issues of the Walking Dead comic series (2003). These and Shaun all constitute legitimate cultural juggernauts that, in their own ways, each helped bring the monster back to life.

Horror icons and monster types throughout history have reflected the fears of the time that birthed them. Werewolves are easy to see as fears of pubescence, of males growing up too quickly to have control over their basest impulses. Dracula was a wealthy, powerful foreigner who seduced and sullied our women. And Frankenstein’s monster was reflective of a fear of advances in modern science…a “where will it end?” hysteria that later recurred in the mad scientist / giant monster movies of the 1950s, when nuclear paranoia was not coincidentally at the forefront of public consciousness.

So what is it about zombies that made them so appealing to audiences of the early 2000s? What is it that makes them so appealing still? What social fears of uniformity, of unstoppable viruses, of mob mentality are we articulating through these mindless hordes?

It’s a question that I find fascinating.

I find it even more fascinating that the real danger in zombie media — almost always, going right back to Romero’s original film — comes from other survivors.

Are zombies actually what we fear? Or do we fear how the danger will change us? Do we fear how quickly and easily we will become the villains? How simply our best laid plans — dealing with Philip, picking up mom and Liz, holing up and waiting for all of this to blow over — will turn, in an instant, to a blueprint of our own destruction?

If we really are the danger — if we as people are the horror movie icon of our own generation — then that explains why there’s never been much interest in crafting a definitive, canonical origin story for zombies. Unlike the Wolfman, Dracula, or Frankenstein’s monster, there’s no one answer as to where they came from, how they behave, or how to deal with them.

Each of those three examples have seen variants through the years, but that’s just what they are: variants. In zombie media there’s nothing but variants.

They could be the result of voodoo, viruses, or radiation. They could be slow and lumbering or fast and ruthless. They could overwhelm you or outlast you. They could be mindless, or they could be corrupted shades of the people you loved.

Shaun of the Dead, wisely I think, doesn’t give us a definitive origin for its threat, which is a clue that zombies are not the important thing here; the story — no matter how big or dangerous or relentless the horde — comes from the characters…how they interact, what they decide to do, how their relationships grow and change.

This is a vagueness that both Hot Fuzz and The World’s End abandoned, opting instead for definite answers, and in those cases I think that it distracts from the power of each film…but we’ll talk about that in the coming weeks.

One thing Wright and Pegg introduce here that does carry through the entire trilogy (together and separately, as it occurs in both the direction and the dialogue) is the concept of echo.

There’s an often-mocked film clip of George Lucas describing the prequel trilogy as being “like poetry.” It rhymes, he says. (And we all know what it rhymes with.) But that’s actually a good way of describing the films that constitute The Blood and Ice Cream Trilogy.

These do rhyme, both in ways that have overt payoffs (Ed’s “cock it” exclamation later becoming firearm advice) and in ways that simply connect disparate moments in artful ways (“What do you mean, do something?”).

At its best this repetition enhances the comedy, but even at its “worst” (a usage of the word that definitely requires quotation marks) it instills in the viewer a feeling of artistic purpose.

Sometimes there’s not much more to the echo than cleverness for the sake of cleverness, but that’s an important reassurance when your film relies on cleverness. It’s a way of cluing your audience in to the fact that it’s worth paying attention. That this is a film that will try to give you a little more. That if you treat what you’re watching with respect, you’ll it in return.

The echoes help to define Shaun as the confident piece that it is. It doesn’t seek to dazzle and distract so much as it does try to suck you into its universe, and erect boundaries between itself and any other horror comedy you’ve seen. While it slips into and out of outright parody territory (see Shaun and Ed singing “White Lines” with a howling silhouette), its foundation is laid firmly upon the complex workings and frustrations of adult friendship. Of group dynamics. Of basic humanity, and how it falters when social convention is violated.

In short, it’s always real. That’s why the death of Shaun’s mother hits the way it does. That’s why Shaun and Liz leaving Ed feels genuinely sad. That’s why David being torn apart by zombies feels unfair, no matter how much of a shit he was.

These things hurt because they are the result of one genre encroaching on another…the horror triumphing over the comedy…the zombies forcing their way into our stronghold.

Which is evidence, if we need it at this point, that the zombies aren’t the important part of this film. They’re an obstacle. A problem unfolding in the background. A periodic danger that must be dealt with, unquestionably at inopportune times.

Like the later Her, Shaun of the Dead crafts a world in which something astounding and impossible happens, and then focuses all of our attention on how a small handful of characters deal with ancillary issues.

The zombies are just a method of advancing the plot…a way of forcing Shaun into action.

They’re symbolic of the world closing in on him, forcing him to do something…and that’s necessary, because Shaun is the kind of person who will choose inaction every time that inaction remains an option.

It might take zombies invading his house to get him off his ass. And once he is off his ass he might realize that he enjoys sitting on his ass and slide right back into that.

But that’s okay. Because at least now he knows. He knows who he is. He had to lose a lot along the way to arrive at that conclusion, and it might be a conclusion he expected from the start, but that was still his journey.

A human journey.

A journey that ends in neither tragedy nor triumph, but with a man understanding, for the first time, that he’s okay with who he already is.

It’s horror, it’s comedy, it’s romance, it’s action, it’s drama, it’s social commentary, and it’s none of these.

It’s Shaun of the Dead, and for most of the world it was a promising and exciting glimpse of a strong, witty, intelligent new film maker.

If we classify Shaun of the Dead as a horror film — and I would, without question — I think it’s one of the best. I’d place it alongside The Shining and Psycho in terms of raw quality. The fact that it’s a comedy doesn’t diminish is impact; if anything, it allows it to resonate in unexpected ways in these savvier and less sincere times. It’s a horror film that appeals with good reason to the audiences of today, and one that has clearly learned from yesterday’s best.

We only had to wait three years for Wright and Pegg’s followup, but the moment it arrived people were already arguing about which film was better. The lack of a clear consensus speaks volumes about how great both films were.

Which do I prefer? You’ll find out next week, when we talk about Hot Fuzz.