Well, this is supposed to post in a couple of hours, so let’s not dawdle. We’re just over a quarter of the way through the film and things are really happening now, so sit back and enjoy my analysis of the next seventeen seconds of The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou.

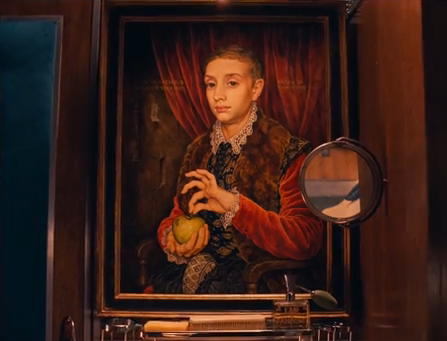

The next day begins with Steve using a Polaroid to take a picture of Ned, explaining that they’re used for continuity. Part of me would like to see the Polaroid camera as some more humorously outdated Team Zissou tech, but that’s only true in a photographic sense. Until very recently Polaroids were used for continuity purposes in film and television production. The reason was that picture quality didn’t matter as much as convenience; the photos would not be distributed to the press or used for promotional materials…they were instead retained so that hair and makeup artists could reconstruct a certain look days or weeks later.

It sounds a little silly, but if you have a film in which your character gets into a fight and comes out of it with a black eye and a bandage — not to mention mussed hair — you’d want a Polaroid of him in that condition, and you’d want to keep it handy. After all, films are not shot in sequence, and it might be another month before you shoot the scene that comes next in the film, in which you’ll want the hair, black eye and bandage all in the same places. You might even have to come back later on to remount a scene because it was discovered too late that the footage, for whatever reason, was unusable. That’s where continuity comes in; you need to make sure your scenes flow, and if bandages and hair styles keep jumping around, it’ll shake your audience out of the experience. In fact, it’s fully possible that in 2004, Anderson himself was using Polaroids for continuity reasons while filming The Life Aquatic.

So as long as we see the Polaroid camera as part of Steve’s production equipment rather than oceanographic equipment, it’s at least relatively current.

But, then, shouldn’t we be asking ourselves the question of why Steve is concerned with continuity? Remember, he’s a documentary filmmaker. Or, at least, he’s supposed to be. He’s not staging scenes, he’s not shooting out of sequence (how could he?), and he’s not constructing an ongoing drama. Shortly we will hear Steve explain that “Nobody knows what’s going to happen. And then we film it. That’s the whole concept.”

Yet we’ve already seen (and heard) that this is not true. Steve does demand a certain editorial control over what gets into the film. Whether it’s a looped line, a staged reconstruction, or even just a demand for the largest amount of footage possible, so that he can better shape it to his ends.

There’s something at least slightly dishonest about this, but we’d be fooling ourselves if we believed that documentaries aren’t usually given shape by their directors. Of course they are; that’s what film-making is. What’s strange here, though, is the notion of continuity.

What’s the suggestion there? The suggestion is that Ned is something right now…and he may not be that thing later. This is a photograph…a frozen moment in time. A man in one very specific state. We need the photograph now for continuity, because he may never be that person again.

It would be pretty Andersonian for the whole continuity thing to be an excuse on Steve’s part to get a picture of his son, but knowing what we know about both Steve (who isn’t sentimental about it) and Ned (who would willingly pose for one), that’s not what’s happening here. It’s just Steve Zissou, once again, controlling and giving shape to the world around him through the medium of film.

Steve offers Ned a handgun, which is hilarious to me in at least three ways. First, because Steve Zissou is the kind of guy who won’t even preface the fact that he’s about to hand you a firearm; he simply holds it out and says, “Here.” Second, Steve Zissou is the kid of guy who lets the gun point up while handing it off, instead of safely down and away from anybody. And third, in a moment that’s almost heartbreakingly adorable, Ned reaches for it out of sheer politeness before he even realizes what it is. Bless his heart.

Of course, Steve’s cavalier attitude toward deadly weapons is emblematic of the general Team Zissou approach to firearms: they don’t know what they’re doing. Nobody seems to have been trained in proper handling or safety procedures. They simply wear their guns against their legs, and while we see them use their weapons later, at no point do we get any suggestion that they’re doing anything other than firing and hoping for the best.

These things are played for laughs, but, as we know, it’s this shrugging attitude toward safety that will end up taking the life of the man politely refusing a gun.

Reinforcing this idea of lax gun safety (and safety for himself, and safety for his crew, and safety in general) while further playing it for laughs, Steve calls down to Anne-Marie, his script girl, asking if the interns get glocks. Not only does he not know if his unpaid interns are carrying firearms, but she replies that they all actually share one. Wowsers.

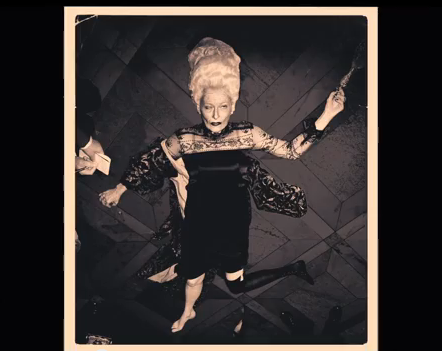

The image we get of Anne-Marie — in addition to being, let’s face it, pretty lovely — is once again evocative of a mermaid. We discussed this during the scene set at Loquasto’s after party, and we see it again now. I understand that this is more of a vague visual suggestion than anything hard and fast, so of course feel free to disagree. I, personally, find it hard to gaze down at Anne-Marie lying down, her hair splayed out behind her, topless, with a green dress, and not see a mermaid sunbathing.

Ned does as he’s told (was there any doubt?) and takes the gun, which causes Steve to smile. Yes, Steve Zissou smiles! I even captured the evidence above.

Ned smiles, too. He’s dressed in the clothes and he’s in possession of correspondence stock that bears the name, but now Ned really is becoming a Zissou, what with him taking the gun and therefore willingly putting himself in danger just because Steve told him to. It’s such a tiny moment, but it’s an impressively dark twist on the paternal bonding experience.

Wolodarsky appears and tells Steve to get on the echo box. He has to slap it to get it working, and the unit swings loosely from its mount. More outdated tech, and another reminder that even the most basic repairs — such as loose mounting screws — go unaddressed.

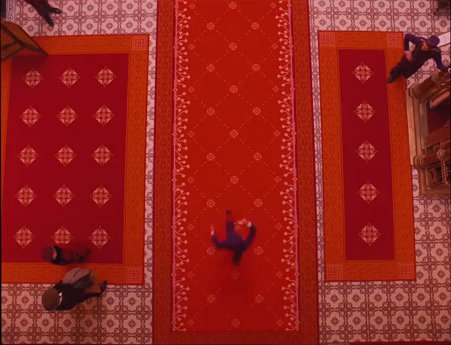

He learns that he has a call from Oseary Drakoulias, which causes him to break into an immediate sprint. It’s interesting to me just how overtly Anderson reminds us of the importance of film in Steve’s life, yet it only stands out to me when I break down scenes detail for detail. When you just watch the film, so much of this passes by unnoticed. That’s always been the thing about Anderson’s approach to detail and characterization, though: he hides everything in plain sight. It’s why you can watch just about any of his films and laugh the entire time, then rewatch them and be a sobbing mess. The film doesn’t change…we just know what to look for the second time through.

It’s not good news. Oseary is Steve’s producer, and the deal with Larry Amin for financing has fallen through. Steve’s understandably upset, but his response to Oseary throws wide open another suggestion of a past that we won’t get to explore deeply: “In other words, you fucked us.”

Oseary’s implied homosexuality is what informs the earlier scene in which we met Larry. Oseary may have been angling for funds, but he was also flirting. The suggestion now is that Oseary and Larry have not come to a financial arrangement, whether or not they came to any other kind of arrangement. Oseary could have frightened him off with his advances. Or he could have enjoyed his company and decided not to press the issue. It’s unclear. Steve’s choice of verb, however, is not. He throws it at Oseary because he knows, at least vaguely, what happened. It’s probably happened before. And he know it will hurt the man, which it does, and the conversation immediately becomes a shouting match.

What’s also worth noting is that it was Steve himself who was rude to Larry earlier on, refusing to see him as worth his time unless he had the kind of money needed to mount the next film. Oseary may have erred on the other side, looking past the money to see too much of Larry Amin.

Either way, regardless of who fucked whom, the money isn’t coming.

I also like the placement of the Belafonte model here…sitting in the window, overlooking the water, so that it could just about be mistaken for the actual ship out at sea. There’s also another set of The Life Aquatic Companion Series on the shelves, and words cannot express how much I wish those were real. If I could own any prop from the film, it would probably be one of those books.*

Ned interrupts — of course politely — and says that he just inherited $275,000. He’s not sure that that amount would make any difference, but when you’re flat broke (as Steve seems to be, though we later find out this is not true) it makes a massive difference. Oseary seems unable to decide whether or not Ned is being sarcastic, and that’s another instance of something tragic being played for a laugh. After all, we know how this story ends: Ned is bankrolling his untimely death.

He believes he’s helping his father. All he’s really doing is investing $275,000 in his own funeral service.

Steve and Ned take off for Oseary Drakoulias Productions. There’s more looming tragedy here being played as comedy; the foreshadowing is really being layered on thick…and yet, once again, if you don’t know what to look for it just glides on by. In this case it’s Steve asking Ned if he can fly a helicopter. Ned replies that he has, in a way that makes it clear he really shouldn’t, and he’s “certainly not licensed in any way, shape or form.”

Steve responds by handing him the keys and saying, “Great. Let’s go.”

Think about that. Not even within the context of what happens later in the film (though that by no means can be far from your mind). Just think about what’s happening here. Handing the keys to an aircraft to somebody who isn’t licensed to operate it. Telling him to take you up into the sky and fly somewhere he’s never been.

Can you imagine anything more dangerous than that? It’s a joke here, as was Steve’s handling of the gun. In each case, the joke is on Ned. There’s only one possible punchline, and it’s a tough one to swallow.

Later in the film, Anne-Marie (in what, if I remember correctly, is her final line) sums up her views on Steve thusly: “We’re being led on an illegal suicide mission by a selfish maniac.” And you know what? You could look up any word in that sentence, and you’d find that she’s not exaggerating. The script girl chose her words carefully, and she’s absolutely correct. Here, on a smaller scale, Steve is doing the same thing by forcing a gun and a helicopter on a man who isn’t trained to use them, and then demanding that he does.

Steve’s pretty clearly a terrible father, and a lousy captain. He’s (at least currently) an inept and destitute filmmaker. He’s a cheating husband, a demanding employer, and a bad friend. And you know what? We haven’t seen anything yet.

Some perfect, gentle foreshadowing in this screen grab, as Klaus watches Ned and Steve depart. He’s shielding his eyes from the sun, but the gesture mirrors his final salute to Ned, when the helicopter takes off for a second and final time in the film.

Yet another thing I’ve never noticed before writing this series. I cannot express how much I love this movie.

Enough foreshadowing yet? I hope not, because Steve and Ned hear some nasty grinding as the helicopter soars, and Steve reveals that he has no idea when it was last serviced. Klaus is supposed to check it every six months…then again, Klaus was supposed to pick Jane up at the airport. He’s not the most reliable crewman, and this specific lack of attention to his duties will ultimately result in Ned’s death.

As much as Steve might believe his “pack of strays” mentality to staffing his ship is a good thing — as might we; it’s a Wes Anderson film, after all — we’re surrounded by evidence that it’s not. Machines are failing, equipment stays broken, and job duties remain unfulfilled. Steve’s legacy is falling apart around him both because of his own lack carelessness, and the inherent carelessness that he finds and fosters in others.

Ned is Steve’s legacy personified. We’re reminded now of how that turns out.

In Oseary’s office, we get another nice look at the difference between Steve and Ned. While Ned stands with his hands behind his back, refusing to even approach the desk until he’s invited to sit down, Steve is behind the desk leafing through one of Oseary’s files. (Possibly one on himself.) So much in this movie just happens, and Anderson trusts us to find it eventually. He draws undue attention to literally nothing, which is almost ironic since The Life Aquatic is easily the film of his with the most visual spectacle.

The wire transfer came through successfully from Kentucky, and Ned is finally invited to sit down. There are a few “hooks on it,” however (another nice aquatic choice of words), and Oseary outlines them. While he does, we get a good view of Noah Baumbach as Philip. Baumbach co-wrote The Life Aquatic with Anderson, as well as Fantastic Mr. Fox, which means he bookends the quality spectrum for Anderson’s films as far as I’m concerned. He’s also a great director in his own right**, though I probably wouldn’t put him on quite the same plane.

The bank apparently wants a drug test for everyone on the crew. Steve looks a bit shifty, but isn’t particularly concerned about this. His ire is quietly raised, however, when Oseary also mentions that “a stooge from the bond company” will be coming along to keep them on budget. Oseary wisely cuts off any protest from Steve by telling him outright that “there’s not a damn thing you can do about that.”

The major revelation here, however, is that Steve must legally swear not to kill the Jaguar Shark. As he already announced to an assembly at Loquasto, this mission is purely one of revenge, so forbidding Steve to kill it goes clearly against his intentions. Ever the gentleman, however, Steve meets Oseary halfway: “I’m going to fight it, but I’ll let it live.” He then immediately inquires about the dynamite he requested, just in case you were willing to believe that Ahab just wants to smack Moby-Dick around a little bit.

Another interesting point comes up here: Oseary tells him he can’t kill the Jaguar Shark, “or whatever it is, if it actually exists.” Granted, Steve is already dreaming up a response that will get him off the hook, but this isn’t the first time that somebody’s questioned the existence of the Jaguar Shark. And, as before, Steve doesn’t pursue the issue.

I find this incredibly fascinating. Put yourself in Steve’s shoes. You go out diving with a friend, a very close friend, and you see that friend get devoured by some monstrous sea creature. When you come to shore and tell everyone what happened, they make comments to the passive effect that you made it up. That there was no creature.

What would your response be? Your friend is dead. You didn’t kill him. Some unknown beast did. You’d make that very clear. You might not be able to tell them what it was, but you saw it happen. You’d plead with them to believe you.

Steve, however, doesn’t do this. People question the existence of the shark, and he shrugs. That’s incredible to me, and I’m not quite sure how to interpret it. Is it because Steve sees the world through a lens, and because he dropped the camera and there’s no footage he can’t be sure that it ever did happen? He saw it happening, but he didn’t capture it happening; that’s a significant difference for Steve Zissou. That’s the difference between fantasy and reality.

Or is it more like what Jane suggested in our last segment? Does this also seem fake? This would square very nicely with the answer Steve gave Captain Hennessey when the topic was breached at Loquasto: “I don’t want to give away the ending.”

Either way, however, Esteban is dead. There was blood in the water. Steve surfaced with hydrogen psychosis.

Did the shark kill Esteban? We learn later that it at least exists, but for now the possibility that that’s not what happened is an intriguing one. Especially since it’s not the shark that kills Ned…it’s Steve, in pursuit of the shark. Another important distinction.

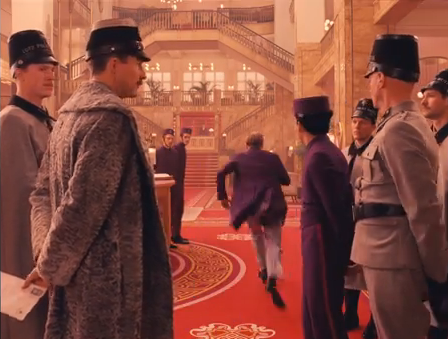

Oseary is off to Zurich, but before he leaves he introduces Steve to the bond company stooge, Bill Ubell. There’s one of those tiny cuts for time that Anderson employs with such tantalizing infrequency: Oseary steps out of his office and into the hallway, then we cut to him stepping out of the hallway and into the lobby area. We lose maybe five steps, and the camera comes along with us so that it feels like a continuous shot, without actually being one. I love this.

Bill Ubell stands, and there’s another lovely, understated moment when Bill glances down at Steve’s hand as though he expects he’ll be able to shake it. Steve’s hand just hangs there. We’re far enough back that we might not notice it. Anderson’s trusting us a lot with this film.

Steve’s distrust of Bill (played by Bud Cort, of Harold and Maude fame) is palpable, and Anderson does a great job of making us complicit in it. He dresses Bill in muted earth-tones, at clear odds with the bright blues and reds of the Team Zissou uniforms. He’s made to look like an interloper not only aboard the ship, but within the film. We even see the three of them squeezed into a tiny elevator, illustrating physically Steve’s inner discomfort at having to share space with the man.

Zissou outright says to Bill that he hopes he’s not going to bust their chops. Bill asks him why he would do that, and Steve responds that he’s a bond company stooge.

Bill replies, “Well, I’m also a human being.” Steve’s uniformly judgmental outlook softens, as should ours. We saw him through Zissou’s eyes, and as funny as the line is, we should also feel at least a little bit ashamed for drawing certain conclusions from Bill’s appearance. His glasses, his bald spot, his cleanly pressed wardrobe. We thought we knew what was stepping into the elevator with Steve, and we were wrong. Anderson took movie wardrobe shorthand and used it against us. We’ve been trained to see one thing, and he reveals to us another. It’s one of the more obvious slights of hand that he pulls in this film, but by no means is it the only one.

That Steve apologizes for feeling exactly what we felt is probably due to his riding high. He’s in a good mood. He has money again. He’s going to do his movie. Philip is getting him dynamite. He’s feeling good, and Devo’s rollicking “Gut Feeling” wells up on the soundtrack…but we’ll talk about that next time.

We end this recap on Steve inviting Ned and Bill to share a cheer with him, in the name of teamsmanship. What a fantastic invented word, by the way. It’s Steve expressing something that he doesn’t otherwise have a word for. It’s not friendship, it’s not companionship, and it’s not even a relationship. It’s teamsmanship. The state of being a teamsman.

That speaks volumes to me about Team Zissou. It’s not about bringing any expertise to the mission, it’s not about being a capable leader, and it’s not even about doing your job. It’s about being part of a team. That, in itself, is its own reward…at least in Steve’s mind. It’s why his interns are unpaid. (That, and the fact that he doesn’t have any money.) Being aboard the Belafonte is a privilege, and one that should be celebrated.

And so we celebrate, because the Belafonte has just found the final major addition to its crew, and everything is going to be just fine for everyone.

Next: Ned drinks a little too much water.

—–

* Christmas is coming, guys…

** His films The Squid and the Whale and Greenberg are the ones I’d recommend. But be warned: both of them will probably make you ashamed to be alive.