Eight years ago, friend of the website Dave invited me to name my favorite thing from each year of the 1990s. I did that and it was fun! With the 2010s coming to an end in a matter of days, I thought it might be just as fun to look back on some of the few things from the past 10 years that did not make me weep for the future of humanity.

No real rules aside from the fact that I’m picking only one piece of entertainment for each year of the decade. My selections are below, and I’d be genuinely curious to hear about some of your favorites in the comments. (Oh, and I guess rule #2 is that you should check out Dave’s selections as well.)

Eventually I’ll do the 2000s and the 1980s, but, honestly, you know me. Don’t hold your breath.

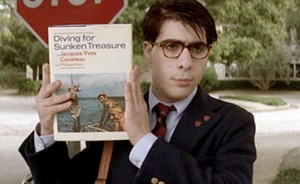

2010 – Submarine

I’ve wanted to do a Fiction Into Film on this one for ages, and I’m sure I’ll get around to it at some point. Suffice it to say a poorly written novel that worked so hard (and so tediously) to be off-putting became, just a couple of years later, one of the most intelligent, charming, beautiful films of the decade. Director Richard Ayoade – who as an actor was involved in a few of my other favorite things ever – found something poignant and resonant in Oliver Tate, reframing him here as a teenager caught somewhere between two futures that are actively diverging before his eyes, despite — and sometimes because of — his attempts to keep everything on track. It’s silly and sad in equal measure, often at the same time, with Oliver’s every decision both feeling small (as they definitely are) while still echoing loudly into the future (as they definitely do). The film also captures what might be the most accurate depiction of depression in popular media — especially in comedy — with Noah Taylor’s performance as Oliver’s father. It’s heartbreaking and upsetting and angering to watch the man settle into comfortable disappointment, acquiescing to a life in which he no longer plays an active role. And then there’s the film’s grandest achievement, Jordana Bevan. She’s precisely the wrong girl for Oliver to chase and, of course, precisely the girl he must chase as a teenager who only just knows better. Yasmin Paige is revelatory, with her wrathful, selfish posturing hiding a core of pain that Ayoade never dwells on; he only gives us enough that we come to realize that Oliver may be the bad influence on her, rather than the other way around. Also, Alex Turner’s soundtrack could almost as easily stand as my highlight of 2010. I can’t say enough good about Submarine, so look forward to my continued raving when I finally get around to that Fiction Into Film.

I’ve wanted to do a Fiction Into Film on this one for ages, and I’m sure I’ll get around to it at some point. Suffice it to say a poorly written novel that worked so hard (and so tediously) to be off-putting became, just a couple of years later, one of the most intelligent, charming, beautiful films of the decade. Director Richard Ayoade – who as an actor was involved in a few of my other favorite things ever – found something poignant and resonant in Oliver Tate, reframing him here as a teenager caught somewhere between two futures that are actively diverging before his eyes, despite — and sometimes because of — his attempts to keep everything on track. It’s silly and sad in equal measure, often at the same time, with Oliver’s every decision both feeling small (as they definitely are) while still echoing loudly into the future (as they definitely do). The film also captures what might be the most accurate depiction of depression in popular media — especially in comedy — with Noah Taylor’s performance as Oliver’s father. It’s heartbreaking and upsetting and angering to watch the man settle into comfortable disappointment, acquiescing to a life in which he no longer plays an active role. And then there’s the film’s grandest achievement, Jordana Bevan. She’s precisely the wrong girl for Oliver to chase and, of course, precisely the girl he must chase as a teenager who only just knows better. Yasmin Paige is revelatory, with her wrathful, selfish posturing hiding a core of pain that Ayoade never dwells on; he only gives us enough that we come to realize that Oliver may be the bad influence on her, rather than the other way around. Also, Alex Turner’s soundtrack could almost as easily stand as my highlight of 2010. I can’t say enough good about Submarine, so look forward to my continued raving when I finally get around to that Fiction Into Film.

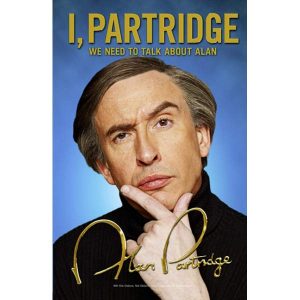

2011 – I, Partridge

I, Partridge is far better than any tie-in book has any right to be, to the point that it’s actually a fantastic read on its own. It’s funny, insightful, and as a writer it’s profoundly instructive. It’s a rich character study that has so much to say on writing, on celebrity, on narcissism, on success (however you’d like to define that). Alan spends several hundred pages painting one image of himself while unintentionally revealing who he really is. As a character, he’s always represented a bit of a balancing act, believing himself to be something other than what we know him to be. But here, in print, it unfolds beautifully, in the grand tradition of unreliable narration, rewarding those who remember Alan’s exploits on television but not leaving behind those who don’t. The structure of the story is recognizable enough, with a central character working so hard to remain oblivious that there’s always this background layer of tragedy. Alan has seen genuine success, but he chooses time and again to dwell on the failures for the sake of redefining them as triumphs. He bullies his own memories, twisting and distorting them until they fit the story he wishes were his. If he actually focused on the things he did right and the lessons he learned along the way, I, Partridge could have been a charming, understated tale of minor celebrity. Instead, it’s a masterpiece of mistruths, and my bookshelf is richer for it.

I, Partridge is far better than any tie-in book has any right to be, to the point that it’s actually a fantastic read on its own. It’s funny, insightful, and as a writer it’s profoundly instructive. It’s a rich character study that has so much to say on writing, on celebrity, on narcissism, on success (however you’d like to define that). Alan spends several hundred pages painting one image of himself while unintentionally revealing who he really is. As a character, he’s always represented a bit of a balancing act, believing himself to be something other than what we know him to be. But here, in print, it unfolds beautifully, in the grand tradition of unreliable narration, rewarding those who remember Alan’s exploits on television but not leaving behind those who don’t. The structure of the story is recognizable enough, with a central character working so hard to remain oblivious that there’s always this background layer of tragedy. Alan has seen genuine success, but he chooses time and again to dwell on the failures for the sake of redefining them as triumphs. He bullies his own memories, twisting and distorting them until they fit the story he wishes were his. If he actually focused on the things he did right and the lessons he learned along the way, I, Partridge could have been a charming, understated tale of minor celebrity. Instead, it’s a masterpiece of mistruths, and my bookshelf is richer for it.

2012 – “Dead Freight”

This is the one that opens with the young boy finding a spider. Both Breaking Bad and its characters struggled to keep the wheels turning after the departure of Gus Fring. That character was a powerful ally, looming adversary, and logistical necessity in one, and the show was even braver than Walter White was in bumping him off. What Heisenberg’s meth empire would look like — and how it would even continue to exist, in any capacity — after that climactic showdown was anyone’s guess. “Dead Freight” was the closest Walt’s post-Fring team got to proving they could succeed on their own. The episode combined two of the show’s defining characteristics — the science and the modern western — for an episode-long, expertly tense train robbery. It’s a classic setup that served as an excellent illustration of the specific knowledge and skills each member of Walt’s crew would bring to the enterprise moving forward. The heist is more than the next step for him and his team; it’s an audition to see who would and who would not be able to pull their weight in the new regime. And so Breaking Bad did what it always did best, teasing what could have been a small sequence into an urgently watchable spiral of action and consequences. It’s a filler episode; some self-contained but exciting way to burn off an hour in the middle of the season. A few minor setbacks that are overcome as soon as they arise, a big happy finale in which the characters get what they want. This is the one that closes with the young boy being shot and killed for witnessing the heist. And with that single gunshot the entire episode becomes one big, traumatic memory, a filler episode retroactively seared into our minds. The entire dynamic of the team changes, because one of them has killed a child. What seemed like evidence that things would be okay immediately becomes proof that we are now in far darker territory. It’s a harbinger of things to come, and looking back from any subsequent episode, the one in which a single child gets murdered actually qualifies as happier times.

This is the one that opens with the young boy finding a spider. Both Breaking Bad and its characters struggled to keep the wheels turning after the departure of Gus Fring. That character was a powerful ally, looming adversary, and logistical necessity in one, and the show was even braver than Walter White was in bumping him off. What Heisenberg’s meth empire would look like — and how it would even continue to exist, in any capacity — after that climactic showdown was anyone’s guess. “Dead Freight” was the closest Walt’s post-Fring team got to proving they could succeed on their own. The episode combined two of the show’s defining characteristics — the science and the modern western — for an episode-long, expertly tense train robbery. It’s a classic setup that served as an excellent illustration of the specific knowledge and skills each member of Walt’s crew would bring to the enterprise moving forward. The heist is more than the next step for him and his team; it’s an audition to see who would and who would not be able to pull their weight in the new regime. And so Breaking Bad did what it always did best, teasing what could have been a small sequence into an urgently watchable spiral of action and consequences. It’s a filler episode; some self-contained but exciting way to burn off an hour in the middle of the season. A few minor setbacks that are overcome as soon as they arise, a big happy finale in which the characters get what they want. This is the one that closes with the young boy being shot and killed for witnessing the heist. And with that single gunshot the entire episode becomes one big, traumatic memory, a filler episode retroactively seared into our minds. The entire dynamic of the team changes, because one of them has killed a child. What seemed like evidence that things would be okay immediately becomes proof that we are now in far darker territory. It’s a harbinger of things to come, and looking back from any subsequent episode, the one in which a single child gets murdered actually qualifies as happier times.

2013 – The Last of Us

It was a good decade for games, but only one of them rose to be my favorite thing of its release year. The Last of Us joined Fallout 3 and The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker as one of very few games that I bought an entire console to play, and I don’t regret it one bit. The Last of Us is a zombie game that doesn’t actually have all that much to do with zombies. They’re an ongoing threat and they pop up when it’s time for a good scare, but the game is really about one central relationship. You play as Joel, a weary middle-aged man who has managed to carve out a space for himself after the collapse of the world around him. He is tasked with escorting Ellie — a young girl who is immune to the zombie plague — to a group of researchers who may be able to use her to synthesize a cure. The fact that a reluctant relationship develops between them, forged in mutual hardship, is not a surprise. The quality with which the development of that relationship is presented, though, is. The writing is excellent, and it’s surpassed by what have to be two of the strongest performances in the medium. Joel and Ellie are characters, but they are characters who feel like people. Their interactions grow and change as their relationship evolves, working through times of distrust, frustration, and anger to earn times of respect, friendship, and love. I’m not sure any other game manages to hit so hard so successfully so many times over. The Last of Us immediately became one of the medium’s most important titles and a cultural touchpoint in general. It’s a complex, horrifying, unforgettable experience. It’s the best thing we got in 2013, and would have been the best thing we got any other year as well.

It was a good decade for games, but only one of them rose to be my favorite thing of its release year. The Last of Us joined Fallout 3 and The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker as one of very few games that I bought an entire console to play, and I don’t regret it one bit. The Last of Us is a zombie game that doesn’t actually have all that much to do with zombies. They’re an ongoing threat and they pop up when it’s time for a good scare, but the game is really about one central relationship. You play as Joel, a weary middle-aged man who has managed to carve out a space for himself after the collapse of the world around him. He is tasked with escorting Ellie — a young girl who is immune to the zombie plague — to a group of researchers who may be able to use her to synthesize a cure. The fact that a reluctant relationship develops between them, forged in mutual hardship, is not a surprise. The quality with which the development of that relationship is presented, though, is. The writing is excellent, and it’s surpassed by what have to be two of the strongest performances in the medium. Joel and Ellie are characters, but they are characters who feel like people. Their interactions grow and change as their relationship evolves, working through times of distrust, frustration, and anger to earn times of respect, friendship, and love. I’m not sure any other game manages to hit so hard so successfully so many times over. The Last of Us immediately became one of the medium’s most important titles and a cultural touchpoint in general. It’s a complex, horrifying, unforgettable experience. It’s the best thing we got in 2013, and would have been the best thing we got any other year as well.

2014 – The Grand Budapest Hotel

Watching the trailers, it was clear that The Grand Budapest Hotel was going to be Wes Anderson’s funniest film to date. What was not clear — what was so wonderfully, expertly unclear — was the fact that it was also going to be his most accomplished. It’s about an experience that becomes a story that becomes a lesson that becomes history, a tale about a young man and his mentor that effortlessly grows into a meditation on humanity and how quickly things fall apart the moment we lose our sense of decency. And all of this happens — with brilliant absurdity, or absurd brilliance — by way of the theft of a single painting. I love Anderson. I love the little universes he creates — these little worlds so familiar and yet so far away — and invites us to explore. The Grand Budapest Hotel might be the one that occupies a reality closest to our own. So close, we’ll realize by the end, that we should be distressed by it. There are strong moments of warmth throughout, and perhaps Anderson’s most effective love story, but as the film unfolds and time marches on, those things are trampled beneath unfeeling boots, ground into nothing. The entire experience is a strange exercise in contrasting tones that is far, far more effective than it should be. It’s just Anderson, not only understanding both sides of the human experience but also understanding how exactly they fit together, what they amount to, and why we’ll never be completely free of either.

Watching the trailers, it was clear that The Grand Budapest Hotel was going to be Wes Anderson’s funniest film to date. What was not clear — what was so wonderfully, expertly unclear — was the fact that it was also going to be his most accomplished. It’s about an experience that becomes a story that becomes a lesson that becomes history, a tale about a young man and his mentor that effortlessly grows into a meditation on humanity and how quickly things fall apart the moment we lose our sense of decency. And all of this happens — with brilliant absurdity, or absurd brilliance — by way of the theft of a single painting. I love Anderson. I love the little universes he creates — these little worlds so familiar and yet so far away — and invites us to explore. The Grand Budapest Hotel might be the one that occupies a reality closest to our own. So close, we’ll realize by the end, that we should be distressed by it. There are strong moments of warmth throughout, and perhaps Anderson’s most effective love story, but as the film unfolds and time marches on, those things are trampled beneath unfeeling boots, ground into nothing. The entire experience is a strange exercise in contrasting tones that is far, far more effective than it should be. It’s just Anderson, not only understanding both sides of the human experience but also understanding how exactly they fit together, what they amount to, and why we’ll never be completely free of either.

2015 – “Milk Money”

Schitt’s Creek is my show of the decade, period. It started out feeling like a lesser (but still funny) retread of Arrested Development, but within a season found a different and surprisingly adorable voice of its own. Both shows are about formerly wealthy families who have to struggle through less-opulent times in the present. But whereas the Bluths were almost uniformly bad people (varying degrees of bad, admittedly), the Roses are decent human beings who have just been sheltered by wealth too long to have to exercise that decency. So, fine, two equally valid families to explore, but what really makes Schitt’s Creek stand out to me is the fact that it manages to find real comedy in human decency. Arrested Development, in that sense, had it easy; it’s funny when people are assholes. Schitt’s Creek has to work harder to get the same number of laughs out of good people, and for a season or so I wasn’t sure it would really be able to keep up the steady stream of laughs a sitcom should. (Pathos and emotion and warmth yes yes, fine, but laughs?) Season two’s “Milk Money” isn’t my favorite episode, but it’s the one that made me realize the show could absolutely do it, regularly, without needing to resort to meanness or negativity. “Milk Money” is a simple farce based on a simple misunderstanding that is resolved just as simply, and it’s a riot. Johnny Rose — the always amazing Eugene Levy — gets the flicker of an idea to traffic in raw milk, and that flicker expands by degrees until he’s caught attempting to offload 120 gallons of contraband with his daughter and Mayor Schitt — a hilariously panicky Chris Elliott — in reluctant cahoots. I’m a sucker for sap, so had Schitt’s Creek delivered emotional stories with only periodic laughs I probably still would have loved it, but “Milk Money” demonstrated that this wouldn’t be an either/or situation. The sweetest show on television is also the funniest.

Schitt’s Creek is my show of the decade, period. It started out feeling like a lesser (but still funny) retread of Arrested Development, but within a season found a different and surprisingly adorable voice of its own. Both shows are about formerly wealthy families who have to struggle through less-opulent times in the present. But whereas the Bluths were almost uniformly bad people (varying degrees of bad, admittedly), the Roses are decent human beings who have just been sheltered by wealth too long to have to exercise that decency. So, fine, two equally valid families to explore, but what really makes Schitt’s Creek stand out to me is the fact that it manages to find real comedy in human decency. Arrested Development, in that sense, had it easy; it’s funny when people are assholes. Schitt’s Creek has to work harder to get the same number of laughs out of good people, and for a season or so I wasn’t sure it would really be able to keep up the steady stream of laughs a sitcom should. (Pathos and emotion and warmth yes yes, fine, but laughs?) Season two’s “Milk Money” isn’t my favorite episode, but it’s the one that made me realize the show could absolutely do it, regularly, without needing to resort to meanness or negativity. “Milk Money” is a simple farce based on a simple misunderstanding that is resolved just as simply, and it’s a riot. Johnny Rose — the always amazing Eugene Levy — gets the flicker of an idea to traffic in raw milk, and that flicker expands by degrees until he’s caught attempting to offload 120 gallons of contraband with his daughter and Mayor Schitt — a hilariously panicky Chris Elliott — in reluctant cahoots. I’m a sucker for sap, so had Schitt’s Creek delivered emotional stories with only periodic laughs I probably still would have loved it, but “Milk Money” demonstrated that this wouldn’t be an either/or situation. The sweetest show on television is also the funniest.

2016 – “Parker Gail’s Location is Everything”

The Bojack Horseman episode “Free Churro” almost took the 2018 slot. In tandem with I, Partridge and “Parker Gail’s Location is Everything,” that would have made for a trilogy of selections in which some delusional individual opens his mouth and forgets how to close it. Documentary Now is great, even at its weakest, and this is far and away my favorite episode. It’s a one-man showcase (…nearly) for Bill Hader, which would be recommendation enough on its own, but it’s also expertly written and structured. Taking as its inspiration “Spalding Gray’s Swimming to Cambodia,” this episode doesn’t skewer Gray as much as it skewers artistic posturing. Hader plays Parker Gail as a meticulous creation of self, building an identity that he then works relentlessly to maintain. Which — necessarily to some degree — every artist does. Hell, every person does, but artists put themselves on display. Even keeping one’s self out of the public eye is a kind of display. That’s ripe enough for comedy, but what this episode puts Gail through is also sad. His calculated wit and creative wallowing is punctured many times over by interjections from others, including his ex-girlfriend (who objects to being misrepresented in Gail’s monologue) and his parents (whose divorce Gail relies on for sympathy despite the fact that they remain happily married). Gail’s monologue — a story about having to move out of his loft — is told compellingly enough that it actually hurts a bit whenever somebody reveals the truth behind it, deflating the artistry. But that’s also the fun of it. Gail doesn’t exist in our reality, but “Parker Gail’s Location is Everything” is essential, humbling viewing for artists of any kind. It’s a good way for us to keep ourselves honest. We all have an image to maintain. But if that image were yanked out from beneath us…how far would we fall?

The Bojack Horseman episode “Free Churro” almost took the 2018 slot. In tandem with I, Partridge and “Parker Gail’s Location is Everything,” that would have made for a trilogy of selections in which some delusional individual opens his mouth and forgets how to close it. Documentary Now is great, even at its weakest, and this is far and away my favorite episode. It’s a one-man showcase (…nearly) for Bill Hader, which would be recommendation enough on its own, but it’s also expertly written and structured. Taking as its inspiration “Spalding Gray’s Swimming to Cambodia,” this episode doesn’t skewer Gray as much as it skewers artistic posturing. Hader plays Parker Gail as a meticulous creation of self, building an identity that he then works relentlessly to maintain. Which — necessarily to some degree — every artist does. Hell, every person does, but artists put themselves on display. Even keeping one’s self out of the public eye is a kind of display. That’s ripe enough for comedy, but what this episode puts Gail through is also sad. His calculated wit and creative wallowing is punctured many times over by interjections from others, including his ex-girlfriend (who objects to being misrepresented in Gail’s monologue) and his parents (whose divorce Gail relies on for sympathy despite the fact that they remain happily married). Gail’s monologue — a story about having to move out of his loft — is told compellingly enough that it actually hurts a bit whenever somebody reveals the truth behind it, deflating the artistry. But that’s also the fun of it. Gail doesn’t exist in our reality, but “Parker Gail’s Location is Everything” is essential, humbling viewing for artists of any kind. It’s a good way for us to keep ourselves honest. We all have an image to maintain. But if that image were yanked out from beneath us…how far would we fall?

2017 – Get Out

I remember reading an interview with Jordan Peele in the runup to Get Out. He spoke about horror and comedy having very similar rhythms, which served him well when making this film. That is interesting! But it could also just have been a way of convincing people to pay for a scary movie made by a comedian. It turned out to be more than marketing, however; it was a neat bit of insight from someone who just made one of the best horror films of the decade. (I’m honestly not sure whether it was better than It Follows; that and Get Out are my top two.) It’s also one of the best comedies of the decade, and one of the best social satires of the decade. And it’s all of those things at the same time, each aspect elevating the others rather than holding them back. To say much about the plot would spoil some of its best surprises, but certainly everybody knows by now that it’s a racially charged story, providing inherent tension when protagonist Chris meets his white girlfriend’s family. Finding comedy in that premise is easy; finding horror is, sadly, not much more difficult. The film’s most insightful moments, however, come when Chris is surrounded by a sort of positive bigotry, with white people praising his appearance, gazing upon him in fascination, asserting that they would have voted for Obama for a third term if they could have…granted, all of that hides something very ugly in the world of the film, but it’s the sort of problematic overcompensation that hides something differently ugly in our world. Get Out is harrowing and hilarious by turns, but it’s also instructive. Viewers won’t see themselves in the villains’ worst moments, but they very likely will see themselves at their most seemingly benign. And any overlap is frightening in itself.

I remember reading an interview with Jordan Peele in the runup to Get Out. He spoke about horror and comedy having very similar rhythms, which served him well when making this film. That is interesting! But it could also just have been a way of convincing people to pay for a scary movie made by a comedian. It turned out to be more than marketing, however; it was a neat bit of insight from someone who just made one of the best horror films of the decade. (I’m honestly not sure whether it was better than It Follows; that and Get Out are my top two.) It’s also one of the best comedies of the decade, and one of the best social satires of the decade. And it’s all of those things at the same time, each aspect elevating the others rather than holding them back. To say much about the plot would spoil some of its best surprises, but certainly everybody knows by now that it’s a racially charged story, providing inherent tension when protagonist Chris meets his white girlfriend’s family. Finding comedy in that premise is easy; finding horror is, sadly, not much more difficult. The film’s most insightful moments, however, come when Chris is surrounded by a sort of positive bigotry, with white people praising his appearance, gazing upon him in fascination, asserting that they would have voted for Obama for a third term if they could have…granted, all of that hides something very ugly in the world of the film, but it’s the sort of problematic overcompensation that hides something differently ugly in our world. Get Out is harrowing and hilarious by turns, but it’s also instructive. Viewers won’t see themselves in the villains’ worst moments, but they very likely will see themselves at their most seemingly benign. And any overlap is frightening in itself.

2018 – Superorganism

Every so often I’ll hear a song on the radio that I immediately love, and I’ll look further into the artist before I realize — reluctantly — that I don’t actually like their material overall. In March of 2018 I heard Superorganism’s “Everybody Wants to be Famous” and figured there was no way the band would be as good as I hoped they were. The song was perfect. Sunny, poppy, spacy, weird, infectious…it wasn’t even worth looking further into Superorganism because I knew it couldn’t be sustained longer than a song or two. Then I listened to “Everybody Wants to be Famous” multiple times a day for a couple of weeks, and decided I owed them money. I bought their self-titled debut fully comfortable with the fact that I’d only listen to that one song with any regularity, and instead kept the entire thing on near-constant repeat for the rest of the year. It was good writing music, good driving music, good relaxing music. It was funny and clever and creative, with every song grabbing me in its own way, no track feeling quite the same as the ones on either side of it, but all of them clearly of a cohesive piece. I’ve largely checked out of current music, but that’s because so little of it does what Superorganism seems so effortlessly able to do. The band and this album carve out an identifiable and unique personality, and it’s one worth spending time with. It’s exciting music. It’s music that matters. It’s music you don’t just enjoy, but which transports you to another universe, briefly, where this is what life sounds like. It takes a lot to find a place on my list of favorite albums at this point, but this one managed it easily. I cannot wait for the followup.

Every so often I’ll hear a song on the radio that I immediately love, and I’ll look further into the artist before I realize — reluctantly — that I don’t actually like their material overall. In March of 2018 I heard Superorganism’s “Everybody Wants to be Famous” and figured there was no way the band would be as good as I hoped they were. The song was perfect. Sunny, poppy, spacy, weird, infectious…it wasn’t even worth looking further into Superorganism because I knew it couldn’t be sustained longer than a song or two. Then I listened to “Everybody Wants to be Famous” multiple times a day for a couple of weeks, and decided I owed them money. I bought their self-titled debut fully comfortable with the fact that I’d only listen to that one song with any regularity, and instead kept the entire thing on near-constant repeat for the rest of the year. It was good writing music, good driving music, good relaxing music. It was funny and clever and creative, with every song grabbing me in its own way, no track feeling quite the same as the ones on either side of it, but all of them clearly of a cohesive piece. I’ve largely checked out of current music, but that’s because so little of it does what Superorganism seems so effortlessly able to do. The band and this album carve out an identifiable and unique personality, and it’s one worth spending time with. It’s exciting music. It’s music that matters. It’s music you don’t just enjoy, but which transports you to another universe, briefly, where this is what life sounds like. It takes a lot to find a place on my list of favorite albums at this point, but this one managed it easily. I cannot wait for the followup.

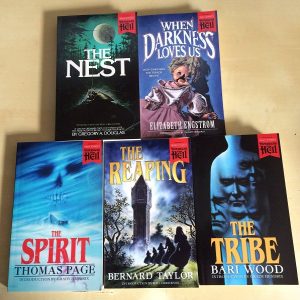

2019 – Paperbacks from Hell

Paperbacks from Hell by Grady Hendrix is a good book. It’s a fascinating look at vintage horror paperbacks and their trends — narratively, artistically, commercially — that is often funny and rarely dismissive. It does its best to treat each of its subjects with respect…though, admittedly, a number of those subjects don’t allow for that. But the Paperbacks from Hell I’m spotlighting here is not that book; it’s a series of horror reprints that followed on from Hendrix’s book, giving a great selection of forgotten horror releases a second life. It gives these always weird and sometimes excellent books the chance to find a new audience, and I love that I no longer have to rely on Hendrix’s summaries and interpretations. This isn’t meant as any kind of slight; Hendrix is a compelling and intelligent curator, but experiencing a work in its original context, on its own terms, will always be preferable to me than somebody’s selected interpretations. Paperbacks from Hell — the reprint series — is in the middle of its second and hopefully-not-final batch of releases, but 2019 saw the release of the first five, and they were great selections. Some of them were exactly the sort of pulp-horror monster-mashing idiotic fun I’d expected (cockroaches in The Nest, Bigfeet in The Spirit), but most of them surprised me with how much genuine merit they had. Jewish horror The Tribe provided a fascinating slice of what monsters look like (and what monsters are) to another culture, and two others were just brilliant works in their own right (The Reaping reached near-greatness, and When Darkness Loves Us ran circles around greatness). I can’t recommend this series enough, if only because it’s a chance to dip back into a part of history most of us were foolishly okay with having forgotten.

Paperbacks from Hell by Grady Hendrix is a good book. It’s a fascinating look at vintage horror paperbacks and their trends — narratively, artistically, commercially — that is often funny and rarely dismissive. It does its best to treat each of its subjects with respect…though, admittedly, a number of those subjects don’t allow for that. But the Paperbacks from Hell I’m spotlighting here is not that book; it’s a series of horror reprints that followed on from Hendrix’s book, giving a great selection of forgotten horror releases a second life. It gives these always weird and sometimes excellent books the chance to find a new audience, and I love that I no longer have to rely on Hendrix’s summaries and interpretations. This isn’t meant as any kind of slight; Hendrix is a compelling and intelligent curator, but experiencing a work in its original context, on its own terms, will always be preferable to me than somebody’s selected interpretations. Paperbacks from Hell — the reprint series — is in the middle of its second and hopefully-not-final batch of releases, but 2019 saw the release of the first five, and they were great selections. Some of them were exactly the sort of pulp-horror monster-mashing idiotic fun I’d expected (cockroaches in The Nest, Bigfeet in The Spirit), but most of them surprised me with how much genuine merit they had. Jewish horror The Tribe provided a fascinating slice of what monsters look like (and what monsters are) to another culture, and two others were just brilliant works in their own right (The Reaping reached near-greatness, and When Darkness Loves Us ran circles around greatness). I can’t recommend this series enough, if only because it’s a chance to dip back into a part of history most of us were foolishly okay with having forgotten.