When I covered the only three seasons of Star Trek, what we now call The Original Series, it was mainly out of historical interest. It was an important show that I’d — for the most part — never seen. I wanted to experience it, enjoy it, poke a li’l fun at it, and move along.

I ended up liking it quite a lot, though. I knew I’d be able to appreciate it, but I didn’t expect to come away from it as a genuine fan. The fact that I did was a nice surprise. Then I watched the films, and they were — for the most part — pretty good. Some I loved, but mostly they felt like slightly longer episodes of more-or-less average quality. I’m sure that was enough for fans who didn’t have BluRays and DVDs to turn to at the time, but for me it was just another six adventures that weren’t as good as the show usually was. I wish I had something more insightful to say about them, but I’ll cover them another day, probably.

Point is, I’d finished with The Original Cast. I really wanted to see Deep Space 9. But something stood between them: The Next Generation.

I could have skipped it, at least for the time being, but I figured, hey, why not check it out? I’d heard good things, and I know a few folks were curious to hear my thoughts about it. Unlike The Original Series, I had never seen a full episode of The Next Generation. I remember it airing regularly in syndication, so I’m sure I caught a few minutes here and there after Batman: The Animated Series, but it never grabbed me and, in fairness, I never let it. I didn’t have any interest. I had friends who adored it, but I didn’t really care to check it out.

That means that I went into this show even fresher than I went into The Original Series, and I had no idea whether or not I’d like it, nor did I know whether or not I’d want to cover it. Committing to a full seven series-in-review posts would have been a bit much, and I’m glad I didn’t make that commitment, because I sure as hell would have run out of things to say. I will say this, though: I think it’s a better show than The Original Series…even though I didn’t like it as much.

That’s just a matter of personal preference, of course. The cast was fantastic. It had great characters and ideas, even in most of its worst episodes. It also had a much higher number of great episodes, but since it had a much higher number of episodes overall, maybe that’s not a fair point.

I ended up in a sort of strange position: I liked it, but didn’t have enough to say to justify a whole series of posts. And I didn’t want to ignore it, because I thought it was worth documenting — in some way — the things that resonated with me.

I’ve settled on doing a top 10. This is by no means definitive. When I rewatch the series, this will change, without question. Maybe not the top spot, but everything else will jiggle around, at least a little bit. This is me as a first-time viewer, bringing all of my own baggage to the show and engaging with it on my terms rather than its own. It’s not fair, but it’s honest.

For other newcomers to the show, this might serve as a nice sampler of episodes; I was a newcomer, and these are the ones that I loved most. If you want to start somewhere, maybe one of these will interest you. For longtime fans of The Next Generation, these 10 little windows into my experience with the show should give you a pretty good idea of what I enjoyed, what I didn’t enjoy, and the reasons for each. In that way, I hope that folks can get something out of my unexpectedly enjoyable journey through a piece of TV history that I missed completely.

If you want some idea of the episodes that didn’t quite make my top 10 but were in firm consideration, here are another 10. Consider them either honorable mentions or the rest of a top 20 that I was too tired to finish. Either works! “A Matter of Honor” (season 2, episode 8), “Who Watches the Watchers” (season 3, episode 4), “The Defector” (season 3, episode 10), “Captain’s Holiday” (season 3, episode 19), “Devil’s Due” (season 4, episode 13), “Half a Life” (season 4, episode 22), “Conundrum” (season 5, episode 14), “I, Borg” (season 5, episode 23), “The Inner Light” (season 5, episode 25), “Lower Decks” (season 7, episode 15)

As you can see, season one was a big pile of crap.

Anyway, on to the top 10, and let me know what your favorites were. It’s interesting for me to see (already, as a newcomer) which much-loved episodes did nothing for me, and which much-hated episodes I liked, so keep it coming!

#10: “Attached” (season 7, episode 8)

I absolutely loved “Attached,” which is something I can say about any of the episodes on this list, but I want to emphasize it here, because it’s love alone that elevates it for me. (How appropriate!) There are better episodes. Smarter episodes. Funnier episodes. More memorable episodes. You get the idea. “Attached” isn’t quite a guilty pleasure — I think it’s genuinely good — but it would be dishonest for me to say that it’s really one of the 10 best things The Next Generation ever did. Instead, it’s just one of my 10 favorites.

The central premise is interesting: A planet wishes to join the Federation, but not the entire planet. The population is split into two factions, basically, and only one has any interest in joining. Captain Picard and Dr. Crusher beam down to chat with the leaders of the interested faction…but the two never arrive. They end up, instead, in what I’ll simply call enemy territory. In The Original Series’ “The Mark of Gideon,” Captain Kirk beamed down to a planet but never arrived, and there are a million interesting things that that episode could have done with that premise. “The Mark of Gideon” didn’t do any of them, but this episode makes up for it.

That’s just context, though. “Attached” is really about Picard and Crusher. They are prisoners, tethered together mentally by implants, sort of like psychic handcuffs. If they get too far away from each other, they are overwhelmed by nausea and unable to keep moving. But the longer they stay together, the more easily they are able to read each other’s thoughts.

Does any of that make sense? Who cares? It’s an excuse to get the two characters into each other’s minds, which ends up being not just fun and interesting, but important and moving. Coming near the end of the show’s run, “Attached” automatically taps into our own long history with these characters. We know that they care about each other. We know that they are attracted to each other. We know that they have a complicated relationship.

We also know what they can’t say to each other. Previous episodes are littered with loaded pauses, unfinished sentences, and tactical half-truths. I don’t think it’s fair to say that The Next Generation tried to position Picard and Crusher as a “will they or won’t they?” couple, but it did remind us — repeatedly — that they had feelings for each other.

“Attached” has them unintentionally revealing those feelings in the form of pure, shared emotion. Now they can no longer pretend that they don’t know. They can’t dance around it. They can’t clear their throats and wish each other a good night. Now they each know that the other knows how they feel.

Episodes of many shows benefit from unlikely pairings, exploring relationships that usually go unexplored on a weekly basis. Here, though, The Next Generation benefits from shining a brighter light on a very likely pairing. We’ve seen Picard and Crusher together often, sometimes for plot reasons, and sometimes because they simply enjoy each other’s company. They even dine together regularly, and one of this episode’s loveliest moments is a tiny reveal: Crusher makes elaborate meals instead of simple ones because she wants to make Picard happy…but Picard doesn’t like the elaborate meals and prefers simplicity. They were both too polite to say how they really felt.

But, of course, that’s just one revelation, and it foreshadows a much larger, more significant one: They now know exactly how much the other wants to be with them, and the fact that they are learning about and dealing with that as they are escaping an enemy prison is a great way of keeping the episode interesting outside of its (admittedly very good) character moments.

Once they each know how the other feels, there’s no going back. There’s no room for personal diplomacy or feigned ignorance. They’ve been forced into the next stage of their relationship; they just need to decide what that stage will be. Many answers could have worked, but I love the maturity of the answer that “Attached” provides: They know how they feel, yes, but that doesn’t mean that they are obligated to act upon it. They are both adults. Professionals. Friends. They’d enjoy spending the night together, but are they prepared for what the morning would bring?

And so they decide to not be together, and the fact that they actively make that decision means that the relationship has advanced. It’s not a reset button. It’s not a return to awkward social maneuverings and hesitations. It’s a decision reached by two adults who have now shared and discussed the facts at hand. It’s a beautiful and impressively heartfelt conclusion that doesn’t artificially keep the two apart, but rather reinforces the value of the relationship they already have. It’s absolutely lovely.

#9: “The First Duty” (season 5, episode 19)

Unlike his mother, Wesley Crusher is a terrible fucking character. It’s tough enough to have a “whiz kid” on your show without it getting annoying, but the number of times Wesley saved the day when the more-experienced leaders around him failed to do so was frustrating. If The Next Generation were about a crew of morons bumbling their way through space, fine. Instead, it’s supposed to be a crew of hyper-competent spacefarers, which is good, because I like that idea. But the fucking little boy always has to be even more hyper-competent, in spite of his lack of training, experience, or acting talent. Far too often, The Next Generation became The Wesley Show, by sheer volume of the problems that he alone solved.

It was “The First Duty” that redeemed him for me, even though it’s far from a redemption story for Wesley. In fact, it ends up marking the moment at which his entire Starfleet career begins to crumble. But it makes him an actual character, which was a concept puzzlingly absent from most of his appearances on the show. What’s more, it does so in a very recognizable way. What happens when whiz kids go to college? Well…they do some things that aren’t too bright. In Wesley’s case, he participates in a dangerous stunt that gets one of his classmates killed.

That would be enough to kick off a moment of important reflection, but it doesn’t stop there; Wesley also, with the aid of his friends, covers it up, lying to Starfleet and placing the blame on his dead classmate. Why not, right? That kid’s dead; his career is already ruined. What’s the sense in ruining ours, too?

“The First Duty” is excellent because it seems to be aware of a weakness that was built into Wesley’s character from the start. Of course he was an overachieving goody-goody; he was on a ship full of paragons. It’s easy to be a good guy when you are surrounded, exclusively and incessantly, by good guys. But plop him into college, where he will be surrounded by others who are imperfect, still learning, figuring out who they are, and he might latch onto the wrong people. Sure enough, he does. The first time he’s pressured by his peers, he caves in, resulting in the death of a friend. This further snowballs into Wesley lying to his school, his superiors, and his family, which only increases the severity of the repercussions he was trying to avoid.

And, well, good. Wesley should have to pay for this, and he pays dearly. He should have to learn to be a more responsible human being, because he’s clearly never learned it before. And he should cause others to wonder if their faith in him were misplaced. They confused intelligence for virtue, and the fallout is excellently drawn and explored. Picard eviscerating the kid for playing dumb is absolutely brutal, and just as necessary.

There’s no happy ending here. The happy ending was forfeit the moment Wesley and chums put their friend’s life in danger. Now there is only consequence, and consequence is something Wesley never had to face before. Kicked out of the nest, Wesley plummets, and it’s the most realistic thing the kid ever did. The very first time he’s given room to show who he is, he fucks up his entire life. Without a safety net, he pisses away everything he’s ever had.

And I’m not only speaking metaphorically; as punishment, the Academy strips him of the credits he had earned from serving on the Enterprise. He’s wiped his own accomplishments away, because he never learned how to not be a stupid fucking kid. It’s great. It’s meaningful. And it matters. This is Wesley in his truest form. What he does when nobody’s looking is who he really is. He’s not beyond redemption, of course, but he is actively in need of it…which finally makes him feel real.

“The First Duty” is a slap in the face of an established character, which usually doesn’t sit well. But, here, it’s not a character being put through the wringer because the writers ran out of ideas; it’s a character finally being tested…and coming up wanting. It was only easy for Wesley to be chivalrous when he was surrounded by chivalry. That’s an important realization for both him and us.

Allow me also to recommend “Lower Decks,” which serves as a partial sequel to this story. Another of the students involved in the coverup here — Sito — ends up serving on the Enterprise after graduation. Her relationships with Picard and Worf are shaped by the events of this episode, and they’re just as fascinating to explore.

“The First Duty” feels like it matters, which it should, and which is something we can never take for granted in an episodic TV show. Major kudos to The Next Generation for understanding and respecting the gravity of the story it told here.

#8: “A Matter of Time” (season 5, episode 9)

The Next Generation has plenty of episodes that focus on one-off guest characters, but this better than most of them by far, not least because Matt Frewer is a fantastic, funny guest in a fantastic, funny story. Both series of Star Trek I’ve seen have had a sort of spotty relationship with comedy episodes, but “A Matter of Time” succeeds simply because of how great that comedy is. It never becomes wacky to the point that it strains the show’s reality; instead, it revels in the weirdness that exists within the show’s reality.

In this case, the immediately bizarre Professor Rasmussen arrives in a time machine and explains that he is a historian from the future, here to observe the Enterprise crew on their current mission. Sure enough, the mission is an important one; the crew is providing assistance to a planet on the brink of cataclysm. The first-hand knowledge that Rasmussen obtains will help those in the future to better understand what happened. Only…it’s Frewer. The guy is clearly not what he claims to be, but there’s also no way for the crew to disprove those claims. And — thanks to the weirdness already within the show’s reality — who’s to say that a future historian wouldn’t travel back in time to silently study them? Isn’t that one of the least outlandish things that’s ever happened to these people? Something is wrong, but they can’t quite put their fingers on what.

The danger, of course, is that Rasmussen will alter the past, but he stays out of interfering. There’s even a fantastic scene between him and Picard, in which the latter implores him to share his knowledge of how things turn out, but Rasmussen refuses to help. The most he does is question the crew on various topics of historical interest, but even if he’s some sort of spy, he’s not asking about anything that’s classified; all of his questions are about things the crew understands to be common knowledge. Something must be wrong, but whatever it is doesn’t seem like it could be too dangerous…

Ultimately, they learn that Rasmussen really is a time traveler…only he’s not a historian from the future; he’s a thief from the past. His perfectly innocuous questions were meant to help him return to the past — where that knowledge is less common — and profit handsomely. (All that portable tech he crammed into his pockets won’t hurt, either.) But that’s just the broadest outline of the episode, fun as the concept is. Frewer elevates it to brilliance, with his strange demeanor and schoolboy fascination making him feel as much like a quirky scientist from the future as he does a flim-flam man out of time. The fact that his behavior is so far out of place among the Enterprise staff makes it even more difficult for them to read him; the guy comes across like a Looney Tunes character, and his interactions with them are always brilliantly off balance.

The Next Generation isn’t a comedy, but “A Matter of Time” made me laugh out loud more than most actual comedies do. There’s a big joke at the center of the episode, but the rest is just genuinely excellent comic business, kept afloat by a fun mystery and a lovable, eccentric guest. Frewer is a gifted humorist, and he takes a very good script and manages to wring every drop of comedy out of it for us to enjoy. Even in his simplest moments and most direct conversations, he finds some degree of humor in everything from his character’s posture to inflection to expression. He inhabits Rasmussen rather than plays him as a role, and every step in the character’s journey is a delight.

Rasmussen manages to fool the crew without making the crew look like idiots — they know he’s lying, they just don’t know what the lie is — and he manages to be both goofy and thoroughly believable as a con artist attempting to keep everyone else on the back foot. A show that traffics in comedy regularly should be able to pull this off, but a show that dabbles in it only rarely shouldn’t. Surprisingly, and wonderfully, “A Matter of Time” works on every level.

#7: “Frame of Mind” (season 6, episode 21)

The Next Generation dipped its toe into horror a good number of times, and an almost equal number of times, the episodes were big piles of horse crap. A chocolate pudding monster kills a main character. Everyone becomes monkeys and lizards. Stop-motion bugs take over the Federation. It’s awful. Absolute garbage, and rarely the fun kind of garbage. It’s boring garbage, and whenever an episode took on a spooky tone, it didn’t unnerve or worry me; it indicated to me that it wasn’t going to be one I remembered fondly.

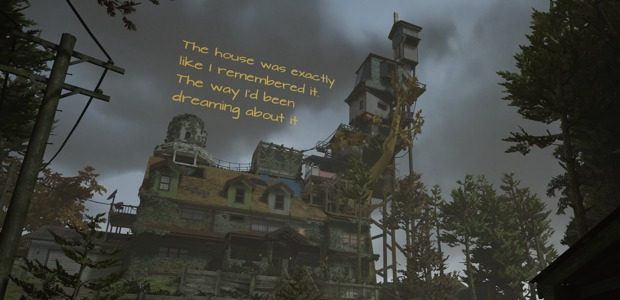

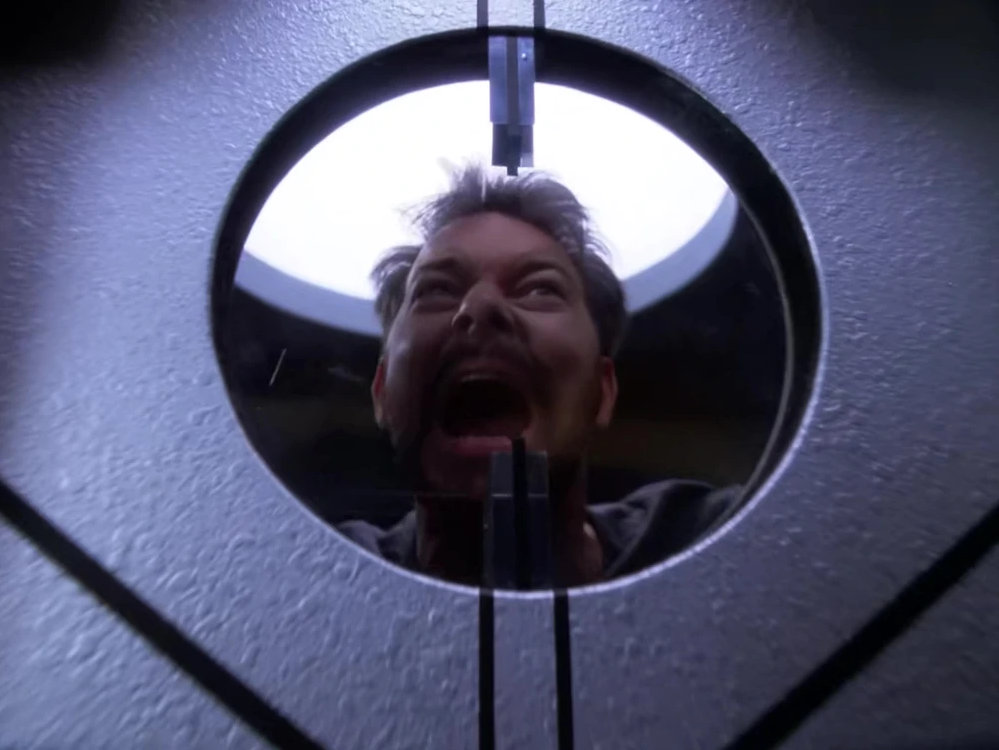

Then there was “Frame of Mind,” which took the most difficult kind of horror — psychological horror — and handled it with aplomb. Not only was it effective, but it was so effective that I genuinely don’t know if I want to watch it again. It was legitimately frightening, and if I had seen this when I were a kid, I am positive that it would have given me nightmares. This isn’t a dipped toe; this is complete submersion, and it’s so well done that I get chills just remembering it.

It works as well as it does, I think, because Riker is very much a “normal” person. Most members of the ship’s crew have quirks that prevent them from being easy “everyman” characters, but Riker is just a guy. Tall, handsome, charming, competent…but still just a guy. This has led to a large number of pretty boring episodes about him, but in “Frame of Mind,” that normalcy is weaponized. Riker is so normal, so easy to identify with, that it’s not easy to maintain distance. If this is happening to him, it’s easy to imagine it happening to us.

The story unfolds in such a way that it’s never clear what is really happening and what is in Riker’s head. Sometimes he’s in Dr. Crusher’s play, as a man who is committed to an asylum against his will…and sometimes he is in that asylum, pleading for someone to recognize his sanity. Sometimes he’s preparing for a dangerous undercover mission, and sometimes he’s being told about how poorly that mission went, and that he murdered several people when it went wrong.

At no point can we believe that Riker actually snapped and murdered anyone, no, but that’s not his problem. His problem is that he’s locked away in an institution without a handle on what’s real, on what happened, or even on who he is. We know that his flashes to life on the Enterprise are at least rooted in the truth, but he doesn’t know that, and the doctors are working to convince him his memories are figments of a diseased imagination…something he gradually comes around to accepting, fighting against the incursion of visions that we, in the audience, know to be true.

It’s horrifying stuff, and Riker’s loosening grip on reality is played marvelously by Jonathan Frakes. Frakes is always good and sometimes great, but in “Frame of Mind” he is masterful, and the episode toys with reality to a degree that very few shows manage to do successfully. As someone who struggles with mental health issues, I’m always on edge when a show tries to do a “losing one’s mind” episode. It’s usually insulting, however well-intentioned, but Riker’s struggle with madness is not played for shock; it’s played for sympathy. The guy is hurting. The guy is scared. The guy is lost. It’s scary because it’s handled with total sincerity. This isn’t happening because the show wants to frighten us; it’s just happening. And that frightens us.

The play, too, could have just been a nice echo of the episode’s themes, but it is instead woven through Riker’s hallucinations so effortlessly that it becomes worrying in itself, with the man breaking down during performances, seeing the set around him turn real, watching characters bleed from one reality into another.

The ending is one of my favorites in the entire show. I won’t give it away, but I will say that the closure Riker achieves just before the credits roll felt like closure to me as well. I never want to revisit this one, and I mean that as an enormous compliment, because it was a near-perfect journey through Hell. It was horrifying and off-putting, and that’s exactly what this story needed to be.

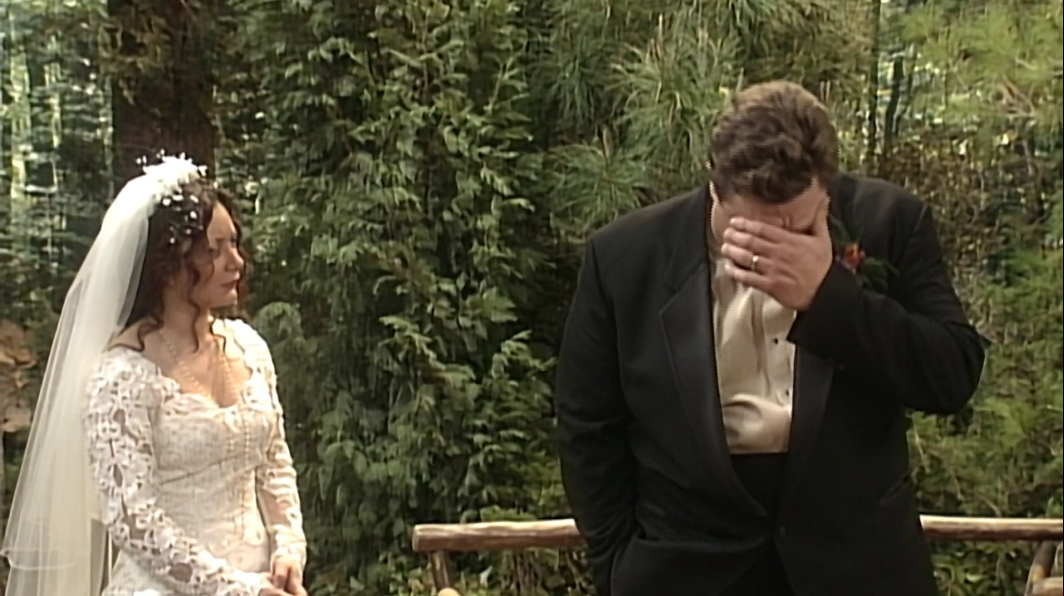

#6: “Family” (season 4, episode 2)

I already knew going in that “The Best of Both Worlds” — the big bad beetle Borg episode — was held in very high regard. I’d never seen it before, but 30+ years of hype didn’t do it any disservice. It was still, clearly, very good. It doesn’t make my list, but that’s because, in my opinion, plenty of other episodes outdo it. One of those episodes is its immediate followup, “Family.”

This was by far the more interesting story to me, and I certainly realize that many of you will disagree. That’s okay. “The Best of Both Worlds” was about a man being kidnapped, modified, and essentially reprogrammed by a race of hostile robot aliens. Scary stuff, well executed. But “Family” is about what happens after that. It explores the mindset of a man who barely escaped death, who must now carry the lingering trauma of that experience, whose career is going to force him to face that precise adversary — and many others — again and again and again. The Next Generation didn’t have to tell this story. It could have just let the audience assume that Picard decided to continue living as a starship captain. Because, well, of course he did. And it’s not as though “Family” gives us a different answer. Patrick Stewart didn’t quit the show; end of mystery.

“Family” gives us an obvious answer, yes, but it also explores that answer. The crew returns to Earth for some much-needed post-Borg downtime, and Picard takes the opportunity to return home to the family vineyard, where life is simpler. Quieter. Easier. Safer. All things that a few episodes ago might not have mattered much to him, but which must seem incredibly appealing right now, after being forcibly modified by space aliens and barely brought home alive.

Picard’s question here is never even spoken, at least not that I remember. Nobody says, “You poor dear; why don’t you stay? We’ll fix up the guest room.” We just watch him go home, and we experience the question through the ways in which he interacts with his estranged brother, with his caring sister-in-law, with his wide-eyed nephew, and with an old friend who offers him a job on Earth, where the space monsters aren’t. It’s a story about Picard’s relationship with his family, and it’s also a story about Picard’s relationship with himself, with the direction he chose in life, and with what really matters to him.

All of that is great enough on its own, but it’s not the only thing that makes “Family” work. True to its title, other characters reconnect with their families as well. My favorite bits are the brief moments between Worf and his adopted human parents. In fact, those moments are fucking incredibly sweet and genuine. He’s embarrassed of them, in theory, but when they actually beam aboard, there is so much love between the three of them that it’s utterly disarming. Worf isn’t the best at showing that love in ways we’d expect from other characters, but it’s there, and it’s sincere. Everything involving the three of them — the genuine care and fondness that they have as a family — is incredibly moving, and it makes it so much easier to picture what Worf’s childhood must have been like. (Easier and a thousand times more amusing.)

Then there’s the bit with Dr. Crusher discovering a holographic message recorded by her late husband for Wesley. In one of the best moments for the character overall, and certainly his best moment before departing for Starfleet Academy, Wesley “meets” his father. The scene is long, well written, and perfectly acted. Father and son are finally face to face, but the communication can only go one way. Wesley gets to spend a little bit of time with the father he never had, but he can’t share anything with his father in return. He finally gets to hear a voice from the past, and then it’s cut off forever.

All of “Family” is well done, to the point that any of it could have been slipped into another episode as the B-plot, and it would have elevated that episode without question. Instead, we get all of it at once, in a sad, funny, thoughtful portrait of what these characters mean to each other.

This is like a Texas Chainsaw Massacre sequel that takes place entirely during the week following the horror, focusing on what happened next to the lone survivor, and that’s fucking brilliant. Space robots are cool and all, but this is the story that will stick with me.

#5: “Birthright” (season 6, episodes 16 and 17)

Going in, the two-part episodes I’d heard about were “The Best of Both Worlds” and “Chain of Command,” and I’d heard very good things about each of them. They were indeed pretty great, but the two-parter that hit me hardest and impressed me most was “Birthright.” Maybe that’s at least partially because I had no idea what to expect. Maybe reading about it will take away from the journey for you. I don’t know. But I do know that it’s one of my favorite episodes (or two of my favorite episodes, I guess), and I’m going to talk about it, so if you are allergic to spoilers, you shouldn’t have read this far anyway.

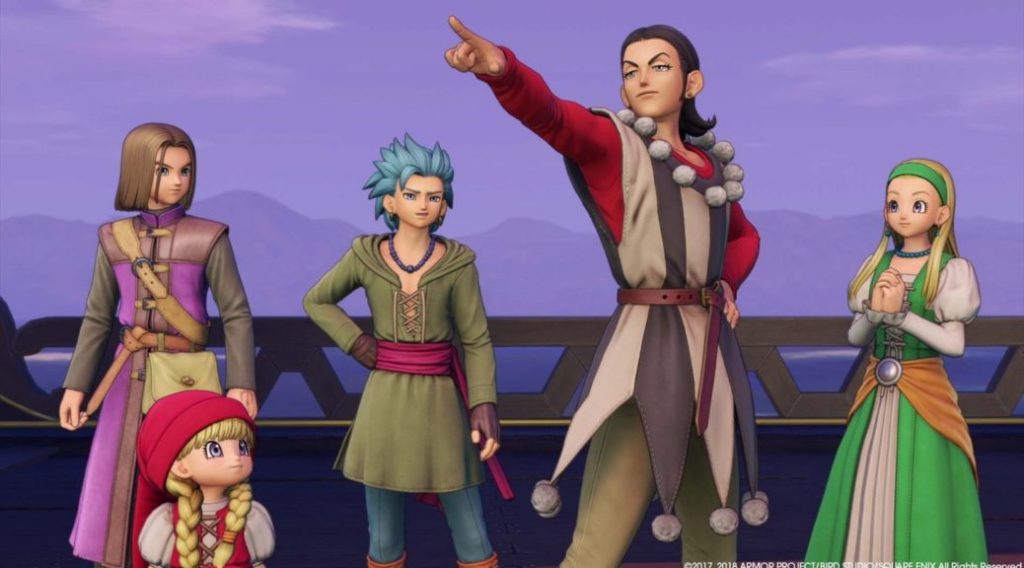

Early in the series, we gradually learned Worf’s backstory. As a child, his Klingon colony was attacked by Romulans, who massacred the residents. Worf survived, though his parents did not. He was adopted and raised by a human couple. Much later, the lie that his biological parents were Romulan sympathizers and responsible for the attack became accepted truth among his people, leading to Worf’s banishment from Klingon society. That’s a lot, but it’s parceled out in small enough chunks that it helps us nicely to understand Worf better. His history isn’t just “stuff that happened and elicits sympathy;” it informs his attitude toward humans, Romulans, other Klingons, friends, colleagues, family members, and so many others. Moreso than any other character, Worf’s history has molded him into who he is, and he is a profoundly compelling character as a result.

All of that is backstory, but it’s necessary for understanding “Birthright.” Here, he is approached by a clearly slimy (and I mean that only somewhat metaphorically) figure who claims that Worf’s parents are still alive, imprisoned by Romulans. Worf doesn’t believe it outright — dude has some fucking well-deserved trust issues — but he also knows that he must find out for himself. He sets out for the Romulan prison colony and does find survivors of the Klingon massacre…but his parents are not among them. That would be that, except that things at the colony are far more complicated than he expected.

The place is indeed a prison, but only in the loosest sense. It’s a secret and insular community in which Klingons and Romulans live not just side by side, but together. In the decades since the massacre, a genuine peace has sprung up between what were once captors and captives. Now they are neighbors. In the vaster reaches of space, the two species are still at each other’s throats, but here, what was once a detention camp is now a town.

Worf is understandably skeptical, but the residents seem sincere in their contentment, and the Romulan elder works closely and relies upon the Klingon elder to ensure something very close to true equity. Eventually, Worf discovers that the Klingons — many of whom were not yet born at the time of the massacre — are forbidden from learning their history, and therefore have no understanding of their own culture.

It’s a sharp ethical dilemma for Worf. Is peace enough? It’s a good thing, yes, but is it worth letting their culture die? The people may survive, but without their history, does it matter? There’s not an easy answer here, and “Birthright” explores both sides of the issue without firmly declaring either side to be correct. Take any two warring countries here on Earth and establish peace, and that’s impressive. But force one side to literally erase its history, its culture, its art, its heroes, its legends, its honor…and did you really establish peace between them? Or did you strip from one side everything that made it worth fighting for? And if you did strip it from them, didn’t you actually conquer them?

More than anything, though, “Birthright” establishes firmly that Michael Dorn is fucking fantastic. He is great beyond my capacity to praise him through words alone. Worf contains multitudes, and we see nearly all of them here, brilliantly realized, with honest pain and anguish, as he sees with his own eyes a vision of peace for his people, which comes at the cost of everything he values about his people.

It’s a fantastic, smart, thought-provoking episode that explores a very difficult question, with both sides making excellent points and neither side having a fix that works for everyone. It’s also an incredible reinforcement of who Worf really is, what he cares about, and what he’s willing to sacrifice for the sake of his heritage…even though that very heritage was quick enough to disown him. It’s incredible stuff, perfectly acted, and a hugely important experience for the character.

#4: “The Measure of a Man” (season 2, episode 9)

There were good episodes prior to “The Measure of a Man,” but this was the first great one. It’s entirely about one single question, and the episode does not look away from it. In fact, it makes sure you pay attention to it, because it’s an important one: Is Data property or an individual?

The Next Generation had its share of clunky social commentary, but this episode — obvious though the parallel is — is elegantly handled, not least because the deck isn’t loaded in favor of an “of course he’s an individual” outcome. Data was built. Data was designed. Data was assembled and activated. All of those things point toward him being an object. A profoundly sophisticated machine, sure, but a machine. The debate is kicked off when a visiting researcher, Bruce Maddox, wishes to study Data, who is far beyond the types of robots anyone else is able to build. (There’s a whole story about Data’s creator that I won’t get into now — and which isn’t revealed in this episode — but allow me to simplify it by saying this: Someone built Data, but that person is gone and nobody knows how he did it.)

Data does not object to being studied in a general sense, but since Maddox’s methods will require him to be disassembled by people who are not guaranteed to know how to put him back together again, it would — in a sense — put his life at risk. Data therefore objects to this particular request, which Maddox finds absurd. How could a machine have the right to object to being studied? It’s elevated to the point of an official Starfleet hearing. A human being of course can’t be ordered to be torn apart for the benefit of medical science, but machines don’t have — and don’t need — any such rights.

Data is artificial life. Which of those two words is the more important one?

In a sense, everyone involved is too close to the problem. Maddox, understandably, sees only the fact that an opportunity to study advanced technology is closed off to him and everybody else in his field. But Picard — who serves with Data on a daily basis, who relies on him as a valued member of the crew, who seeks his counsel — sees only the “person” that Data is. And Riker, who is closer to considering Data a friend, is tasked with arguing against the android’s personhood. As the trial progresses, they discuss Data-specific things. He had a close, reciprocated relationship with a colleague, which suggests humanity. But he can literally be switched off and on at will, which suggests machinery. The trial explores both sides…but Picard — with some outside help — comes to realize that the ultimate judgment won’t be about Data; it will be about the fate of all machines like him.

Turn Data over to Maddox, and that could be tragic for one specific android. But set the precedent for doing so, and all sentient machines will be turned over to those who wish to do as they please, poke around in their workings, experiment on them, and dispose of them. And that’s probably the best-case scenario; Picard quickly comes to realize that the moment you strip personhood from this class of individuals is the moment at which they will start being treated inhumanely. Armies of them will be manufactured to labor in mines, to do work too dangerous for “real” people, to be created and destroyed solely to benefit others. It’s monstrous, and Picard realizes that he is occupying the precise point from which a hideous future could spring. If we bestow our machines with sentience, then it is our obligation to treat them humanely.

The moment it clicks for Picard is affecting and effective, as he realizes that he isn’t just arguing for the rights of an individual, but for the right to individuality for others to come. He is arguing for humanity to take responsibility and have respect for what it creates. The focus stays on one question, but the shift in perspective expands the discussion, the debate, and the decision.

In The Original Series, there was never any doubt for me as to who my favorite character was. It was Bones. It will always be Bones. But in The Next Generation, it’s a tight, tight race between Data and Worf, with Brent Spiner and Michael Dorn doing impeccable work on a weekly basis with characters who felt rich, meaningful, and unique. In a way, I feel bad for both of them; on any other show, they’d be the runaway highlight. Here, they’re together, and they’ll have to settle for being “also great.” (I’m sure that that just breaks their hearts.)

Overall, though, I think Data’s character led to better episodes, and “The Measure of a Man” was just the first of those. It was also the first time, I’d argue, that The Next Generation realized what it could be.

#3: “Tapestry” (season 6, episode 15)

What a truly lovely episode “Tapestry” is. In fact, it’s so good, that I genuinely suspect that I will have nothing to say. Nevertheless, here I go!

The episode opens with Picard dying on the operating table, due to complications with his artificial heart, which he has had since he was in Starfleet Academy. After he passes, he finds his longtime frenemy Q waiting for him. Q is…well, the character is great, and John de Lancie is amazing, but for the purposes of brevity, let’s just say he’s a supernatural being and leave it at that. There’s a little bit of classical Batman villain about the guy — at least in terms of the sheer delight he takes in toying with Picard — but here, at least, his intentions are noble: He’s willing to send Picard back in time, allowing him to make different decisions in his youth and avoid the altercation that led to his needing a replacement heart.

“Tapestry,” then, is what all of us dream of doing: going back in time with the knowledge and experience we’ve gained over the years to do things differently. And, just like all of us would do, Picard fucks everything up.

See, Picard’s artificial heart was established by previous episodes, as was the bar fight that left Picard needing it. The man regrets his actions as a brash and impulsive youth. He was a different person then, as were we all, and he’s embarrassed by that. He’s embarrassed by who he was and what he did and, in at least one case, what he didn’t do.

And so Patrick Stewart — the present-day Picard we know — goes back in time to take over for his younger self, doing things right for a change. We see that young Picard was a womanizer, was quick to violence, was prone to thoughtlessness. He changes those things by virtue of being more mature and measured in his dealings…which causes his friends to see him as disloyal, weak, and full of himself. He also takes the opportunity to make good on decades-old feelings for a female friend of his, but after they spend the night together, she regrets it. His regret has become hers, and it destroys their friendship. At the very least, however, he avoids the fight that cost him his heart…

And we flash forward in this new timeline to see what else it cost him. His milquetoast academy days resulted in him being just another cog in the wheel. He’s not commanding the Enterprise; he’s a nobody, serving under people who don’t know his name and can’t even be bothered to half-ass a compliment when he positively begs for one.

The lesson isn’t “it’s good to be an asshole.” The lesson isn’t “it’s bad to think twice before getting stabbed through a vital organ.” The lesson is, basically, you were a shithead. You, reading this. Too bad. Get over it. It made you what you are. You can spend your entire life regretting your bad decisions, or you can move forward and make something of yourself. Q’s gift to Picard here is a chance to undo his regret not once but twice: first in a very literal way, and second by helping Picard to accept the mistakes of his past and make peace with them.

Yeah, Picard screwed up big time, but that’s a stitch in the grand tapestry of his life, and if he rips it out, what is he left with? It’s a really sweet episode that, ultimately, is left hazy. Did Picard die? I don’t think so; I think he drifted into unconsciousness and Q took the opportunity to do him a big favor. But, being Q, he had to dress it up like some kind of life-or-death test, lest Picard end up suspecting that Q likes him, or something.

The timeline doesn’t really change. Picard still had that fight in the bar. Picard still suffers complications from his artificial heart. But now he’s able to accept the fact that he wasn’t always perfect, wasn’t always a hero, and wasn’t always a role model. It makes him appreciate what he’s accomplished since, rather than dwell on what he failed to accomplish earlier. It’s a masterpiece. And it’s still only my third-favorite episode.

#2: “The Offspring” (season 3, episode 16)

“The Offspring” is a sequel to “The Measure of a Man” in only a very general sense, and yet it feels like a perfect and necessary followup. It was also surprisingly good, considering how easily it could have gone off the rails. “Data’s humanity is on trial” is a setup that would require truly terrible writers to bungle, but “Data builds his own robot and treats her as his daughter” is one that very few great writers could get right. It’s a premise that feels ripe for catastrophe, and I’m still impressed, months after watching it, that it wasn’t one.

Data, again, is a unique android. (Simplifying once more out of necessity, so bear with me.) Nobody knows quite how he works, himself included. But he attends a cybernetics conference and something snaps into place for him, causing him to believe that he might be able to create another android. He does so, and successfully. This upsets Picard, to put it lightly. Building a machine is one thing, but imbuing it with intelligence and personality is creating life. What gives Data the right? Well, as Data suggests in return, the same thing that gives other crewmembers the right. The process is different, but why are only they allowed to create life?

Data’s not being a dick; he genuinely doesn’t understand the difference, which in turn causes Picard to wonder as well what the difference is, to the point that, ultimately, he ends up on Data’s side when Starfleet wants to take the new android away. Their argument is that watching an android learn, develop, and evolve as an individual would provide invaluable insight into A.I. They’re right. Picard’s argument is that they’d be taking a child away from her parent, which is abhorrent. He’s right, too.

So far, so “The Measure of a Man.” However, whereas that episode was ultimately about ideas and debate and philosophy, “The Offspring” is about a very specific character. Data’s daughter, Lal, isn’t a concept; she’s a person, and her struggles to understand who she is, why she’s being argued about, and why she’s being treated like an object, are heartbreaking. Much of “The Measure of a Man” was about future impacts to others. Yes, Data was at the heart of the discussion, but Data is also calm, mature, and not prone to emotional response. Lal is none of those things. Lal is a child, brought to life as the only one of her kind, without any experience or understanding of what’s happening around her or what’s being decided for her. She develops and experiences emotions more rapidly than Data ever could, and they are overpowering. At the same time she’s learning what life is, she’s learning how quickly others will restrict it for her and decide how she must live it.

That’s all heavy, heavy stuff, but “The Offspring” isn’t just that. It’s also funny, as a child who looks like an adult is still learning to interact with others. It’s sweet, as Data sincerely wishes to be a good father to her, without understanding what fatherhood is. And it’s marvelously acted, as Hallie Todd sells Lal’s fear and anguish as well as she sells her naivete and desire to learn. Brent Spiner does incredible work frequently as Data, and if the guest star playing his daughter failed to measure up to that man, well, so be it. Instead, Todd rises right to the occasion, hitting every note perfectly, in a way that never feels artificial or rushed, despite the fact that this particular story could have unfolded over several episodes.

Instead, in a single hour, we follow Lal’s entire life, from her birth, through her education, through her highs and lows, through her eventual demise. We share her entire journey, and it’s fucking devastating. The opening scene led me to believe we were in for a trainwreck, but by the end I started tearing up. And then, as the episode drew to a close, I didn’t cry, dear reader; I wept.

“The Offspring” hits hard, but it’s not manipulative. It’s just a story. It’s just a tiny little window into something that happened. But it’s a great one, and it’s an episode I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since.

#1: “Darmok” (season 5, episode 2)

Boy, things just don’t get better than “Darmok,” do they? Watching this, I had the same sort of response I had to “Balance of Terror” when I watched The Original Series. I was riveted. I didn’t just want to find out what would happen, and I wasn’t just enjoying the show; I was completely and thoroughly invested. And though the episodes are fundamentally different in so many ways, there’s a similarity in that they are both about thinking. For Captain Kirk, it was outthinking. For Captain Picard, it was understanding someone else’s way of thinking. In either case, they would have ended up dead if their wits weren’t sharp enough, though the circumstances themselves couldn’t be more different.

In “Darmok,” Picard and friends meet up with an alien race. They aren’t the first; encounters with this race have been fruitless in the past. The aliens aren’t antagonistic, but they’re impossible to understand, so discussions go nowhere. Picard meets them, and, once again, they make no progress. The aliens don’t understand him, and their own speech — full of proper nouns that are meaningless to our heroes — doesn’t make it clear what they want, either.

Then the alien captain beams Picard down to a planet, and the two meet in person. Nobody on the Enterprise knows what the hell is going on, and Picard assumes he’s been brought there to duel. To his great credit, he refuses. The alien captain tries to give him a blade, and Picard tosses it away. Both of them are trying to explain what they want, and neither of them are understanding the other. Aboard the Enterprise, Riker is having no better luck understanding the rest of the aliens, and every minute that drags by without Picard is a minute of torment for him; all he wants to do is blow up the alien ship and beam the captain back aboard, diplomacy be damned.

It’s a nightmare, basically, and the fact that the alien captain continues to not attack Picard only confuses things more. In fact, he helps Picard get a fire going during the night when the latter can’t do it himself. If the alien is a villain, he’s one in ways that Picard still can’t understand.

It all comes down, ultimately, to the fact that the aliens communicate by metaphor. And because we humans have no concept of the aliens’ histories and myths, their metaphors — referring to individuals and locations and events and situations — mean nothing to us, the same way our metaphors would mean nothing to them. The aliens repeat the same phrases, statements, and instructions, growing despondent as though they are speaking to a child who isn’t paying attention to what he’s told, and as the episode progresses, we don’t just learn what they mean; we figure out what they mean. The Rosetta Stone in this case is a shift in our understanding of language and of communication…not a translation, but an ability to visualize what they are speaking about.

The central repeated phrase, usually by the alien captain, is “Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra.” Which means nothing at fuckin’ all to people who don’t know who Darmok or Jalad are, or where Tanagra is, or what any of those things represent. What it refers to is a historical — possibly mythical — touchpoint for the aliens: two individuals named Darmok and Jalad came together at a place called Tanagra to defeat a powerful beast together, sealing their alliance. “Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra,” as said to Picard, is a suggestion for the two to bond by defeating a tough foe, forging an alliance as legendarily strong.

By way of a more recognizable example, we could describe two antagonistic brothers here on Earth as “Cain and Abel.” It would be immediately clear to us which one was meant to be Cain and which one Abel, because that comparison says a hell of a lot to us, but it would say precisely nothing to somebody from another planet. Or “Rome wasn’t built in a day,” which all of us would understand even if we’d never heard it before, but to someone who doesn’t know if Rome is a city, a car, a food, a university, a concept, a statue, or a tasty tropical drink, it would mean very little. In fact, if they assume that “Rome” is something simple — something that should easily have been built within a day — they might conclude that the overall meaning of the phrase is the opposite of what we intend to convey.

Or consider something as offhandedly simple as “sour grapes.” We understand that phrase, but to an outsider, what’s a grape? Are they meant to be sour? Are they not usually sour? Are they valuable when they’re sour? Are they deadly? Does “sour” refer to the taste, the color, the age, the region in which they are grown? Do people avoid or reach for sour grapes? Assuming we eat them, is it preferable when they’re sour or is that to be avoided? We like some sour things; why wouldn’t we like grapes that are sour? What is the significance? It’s a phrase that says everything to someone who understands it, and nothing to anyone who doesn’t, and that’s fascinating. “Darmok” had me and still has me thinking about how I use language, let alone how space aliens might.

It’s impossible to discuss “Darmok” and give it its due, because it’s a long, brilliantly handled linguistic detective story. (And, don’t worry, I didn’t give it all away.) The episode introduces a puzzle and parcels out clues. Picard puts together enough that you’ll arrive at the same conclusion, but there are plenty of pieces left for you to assemble yourself, as you gradually come to understand what the aliens are saying, without translation, without Picard confirming anything, without somebody feeding you the answers. You hear the same alien language at the beginning of the episode as you hear at the end, but by the end you know what it means.

I remember watching this episode and, afterward, just sitting and thinking. Just exploring my own mind for a while, my own understanding of language and communication, and feeling more and more impressed by what “Darmok” accomplished. Then I spoke with a friend about something completely different and, without thinking (of course), used the phrase, “It’s the tip of the iceberg.” Almost immediately, my mind flashed right back to “Darmok,” and how a phrase that simple could so thoroughly confound somebody who didn’t understand what they were meant to visualize, why visualizing it would be significant, and what — precisely — about a bit of some ice in the sea was important to our conversation.

“Darmok” cheats in the sense that, no, the language isn’t realistic. But it’s not meant to be realistic; it’s meant to be just barely unrecognizable so that when we shift our perspective and realize how they actually convey meaning to each other, we not only understand their language, but understand ours a little better as well. We had more in common than we thought, something illustrated by what might be my favorite Star Trek scene so far, when Picard — in return for the alien captain sharing some of his own people’s legends — shares with him the tales of Gilgamesh.

The two connect and bond over the significance of stories in their cultures — the importance of mythology and common understanding — as the fire dies slowly at their sides, and it’s one of the most moving depictions of personal connection I’ve seen on television.

Understanding somebody with such wildly different experiences isn’t easy, but that scene made the effort feel important. “Darmok” is, without question, my new favorite episode of Star Trek, and it all came down to two men, working hard to understand each other, finally breaking through by sharing tall tales in cold moonlight.

And with that, I come to the end of The Next Generation. Now I can finally move on to the series I’ve been most interested in from the start: William Shatner’s TekWar.

Note: Credit to Saga of the Jasonite for the images. Couldn’t find a way to contact him and ask permission, but here’s hoping the credit is sufficient.