There’s nothing I love more than a great show proving me wrong.

Last week, I said this:

“Hostile Makeover” doesn’t even pretend Dr. Venture is going to succeed. His very first order of business, it seems, is to fire absolutely everybody. Who are these people? He doesn’t care. What did they do for Venture Industries? He’s not interested; he just doesn’t want any of his money going to them. The new phase of his life has only just begun, and he’s taken active steps to ensure it won’t go anywhere.

This week, I happily admit that I fell into Doc and Jackson’s trap. We’re so conditioned to seeing Dr. Venture behave atrociously to people — with incredible short-sightedness and destructive selfishness — that we can see a couple of seconds of him writing on a whiteboard and read an entire season’s arc into it.

And, hey, good. The character work on this show in general — and with Dr. Venture in particular — has been sharp and sturdy. It’s almost impossible to view anything anybody does in complete isolation as a solitary moment; it always informs or is informed by who they are.

It helps the comedy to land and it ends up advancing their stories. Simple gestures or clever lines get to be both small delights and important gears in an increasingly complex (and impressive) machine.

Here’s where else it pays off: the subversion of those expectations.

Dr. Venture writing on the whiteboard as part of a montage was a very important choice of delivery. Because we didn’t hear anything, we assumed the worst: Venture’s a fucking idiot. Now we find out that that isn’t quite the truth. Sure, perhaps he still is one, and the collapse of VenTech likely still looms, but there was a method to his madness.

See, Dr. Venture isn’t going down without a fight. He’s a failure, everybody in his life sees him as a failure, and the newspaper gives over its front page to making it clear that the entire world sees him as a failure…but there’s still a part of him that doesn’t want to be a failure. That believes he’s not a failure. Or, at least, that his failure can be redeemed.

He fired the staff not because he didn’t want to pay them (the ultimate solution, it turns out, is actually to maintain two staffs), but because he wanted to start fresh. He has something inside of him. Something to share with the world. He just needs to get it out. He’s hoping, like Doc Brown before him, to see that headline change. It might still be a bad idea, but it’s an idea. He was in the shadow of his father and lived in unfair comparisons to him until his brother — a talking fist sticking out of an oven — showed up…and then he lived in his shadow and was compared unfavorably to him, too.

Dr. Venture has something to prove.

He’ll never be admired like his father, or brilliant like his brother. But he has something, whatever it is, he’s convinced that he has something, and he fires the staff so that he can rebuild it in aid of his own vision. It’s actually…admirable.

Last week, Dr. Venture was silently portrayed as an asshole. This week he opens his mouth, and we learn he’s a visionary.

Rusty’s back.

In fact, “Maybe No Go” plays like an extended response to “Hostile Makeover.” Whereas nothing happened last week, so much happened this week. Whereas last week was all rising tension, this week things go…really well, actually. For everybody.

That latter point is the most interesting, and most unique in a show like The Venture Bros., which makes a point of picking at the flaws and weaknesses of every single character, so we’ll get to that one in a bit.

First, the lighter side of things: the plots. The Pirate Captain kicks the dart monkey. The Monarch and Gary (who seems to be back to calling himself 21) attempt to eliminate all obstacles between them and Dr. Venture. Wide Wale launches an attack. Hatred and Brock team up for a thrillingly adorable defense of the tower. Billy and Pete square off against their nemesis. And all of these things had a beginning, a middle, and an end. “Hostile Makeover” felt overstuffed and a bit aimless, but “Maybe No Go” takes the same amount of material and weaves a much tighter, more satisfying tapestry.

The main story seemed to belong to Billy and Pete, which is good, because last week I wrote St. Cloud off as a go-nowhere character. And…maybe I’m still tempted to. We’ll see where things go, but this at least proves he can be part of an episode without dragging it to an irritating halt.

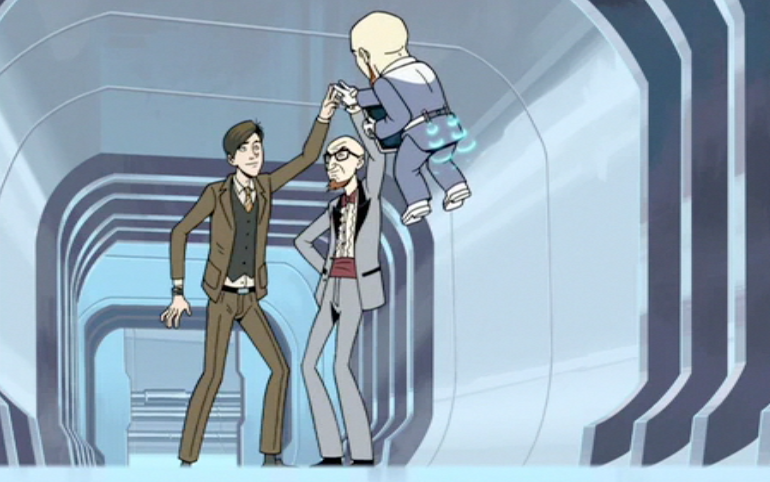

Their plot was one hell of a lot of fun. I remember back when “The Invisible Hand of Fate” aired; I was disappointed that we didn’t get a Billy and Pete version of the title sequence as we did for The Monarch and Dr. Girlfriend in “Shadowman 9: In the Cradle of Destiny” or Dr. Venture and Jonas Jr. in “Powerless in the Face of Death.” We got one here, and it was more than worth the wait.

Billy Quizboy is one of this show’s finest creations, and he’s high on a very long list of very fine creations indeed. His tragedy is a relateable one, and one as ripe for comedy as it is drama.

Billy is one of the few truly capable individuals in the show’s universe…and nobody takes him seriously. While other capable individuals — notably Brock and Dr. Girlfriend — rise through the ranks, earning more respect with every episode, even from their adversaries, Billy languishes. He lives in squalor. He’s mocked and belittled by his friends.

But he’s a skilled surgeon, as well as deeply intelligent and tragically loyal. His struggle to be accepted, admired, and understood has fueled several of the show’s best moments, and came to an incredible, bittersweet head in the hugely underrated “The Silent Partners.”

That episode was one of the few times that the show gave Billy a triumph. This week ends with another. After a long, emotional walk home, the invisible hand of fate gives Billy a boost forward. The “boy genius” did what he felt was right, though all earthly logic was against it. Fortunately for him, a larger, cosmic logic was on his side…and he and Pete are summoned to VenTech, presumably to front the company’s new speculative engineering department.

It’s a sweet moment at the end of an episode that’s almost wall to wall with them. In fact, I’m not sure The Venture Bros. has ever been this generous to its characters before. The Pirate Captain cleans up. Dean proposes the solution that could save the company. HELPeR doesn’t have to cope with a resurrected J-Bot. The Monarch and Gary find a path forward…in the basement. Wide Wale is swiftly and easily repelled in his assault.

And — seriously guys, this was adorable — Hatred and Brock got along. Decades of animosity between the two gave gentle way to a mutual respect. Brock’s always had the ability, but, for once, Hatred had the intel. They worked together, smiled together, and went out for a beer together. It was a more natural fit than I would have guessed possible, especially after last week just about seemed to position them as rivals for the season.

The Venture Bros. is the only show I know that can take a Swedish murder machine and a reformed bad-toucher and turn their mutual jump from a building into a disarmingly sweet denouement. When they fell, most of my concerns about season six fell with them. Even through my concerns last week I knew I was in good hands, but it sure is nice to see that confirmed so quickly.

I’m going to leave you with a couple of questions, which I hope will engender discussion. No wrong answers; I’m just curious what people are thinking.

First: what’s the primary difference between Wide Wale and Monstroso? They dress similarly, they’re both huge, they’re both powerful businessmen…is there a reason we subbed out one for the other? I’m not complaining, I assure you, but it’s not like the switch from The Monarch to Sgt. Hatred in season three. In that case there were (multiple) story reasons, and the massive change in character was important to the show. In this case it feels a lot like a character we’ve already seen, and I don’t know quite why we bothered promoting someone new.

Second: what was in the basement? I’m guessing the original Venture clone farm. I have a reason that my guess is so specific, but I’ll keep that to myself for now. What do you see under those sheets?

And, what the hell, third: are you feeling incredibly stoked for the rest of this season? Because holy shit did I just get invested.