Rudy Ray Moore will always be remembered for Dolemite, but his crowning achievement is without question Petey Wheatstraw, The Devil’s Son-in-Law.

Everything about Petey Wheatstraw represents an improvement over Dolemite, and often a substantial one. It’s smarter and funnier. The acting, writing, casting, blocking, pacing, and fight choreography are much better. Whereas Dolemite felt like a vanity project — which it was, even if it was a more inclusive one than most — Petey Wheatstraw feels like a movie.

Not just a movie, either; it’s a genuinely good movie. Moments approach greatness. Its laughs are almost uniformly genuine. I don’t have any specific insight into Rudy Ray Moore, but I’d be shocked to my core if I found out he had been upset at any point that people had laughed at Dolemite instead of laughing with it. I honestly get the sense he would have still considered that to be a kind of success.

Moore never took himself too seriously. If he caught somebody chuckling at the sight of his beer gut poking out from under his shirt during what was meant to be an exciting kung-fu sequence, I think he still would have been proud of himself. He brought joy to somebody. Maybe not the precise flavor of joy he had intended, but he made somebody’s day that much brighter.

Am I waxing romantic? Maybe, but it’s not without reason. Early in Petey Wheatstraw, our protagonist, as a child, does the same. He confides to his elderly mentor that he wants to grow up and become a comedian. It’s important to him and, he believes, to the world.

“I always wanted to be on stage, making people laugh,” he tells the old man. “So I can try and save the world from some of its misery.” Like Rudy Ray Moore himself, young Petey sees comedy as a noble calling. Let’s be completely fair to the boy: He’s right.

Every human being loves to laugh, and not every human being has the gift of making others laugh. Moore had it, and he knew he did. It was his obligation, therefore, to put it in front of as many people as possible. On stage, on record, on screen. However he could reach those who needed the laughs he could give them, it was his job to do it. The best part? The guy loved his job.

Petey Wheatstraw is an hour and a half of a man loving his job. It’s a horror comedy with a firm moral lesson that Moore as Petey stubbornly refuses to learn. He makes a deal with The Devil, reaps the benefits, and spends the rest of the film trying to outwit Old Scratch. It’s the barest sketch of a plot, but it’s more than enough to get us to a lot of funny places and a few pretty surprising ones.

The film opens with an adult Petey Wheatstraw addressing the audience directly. He is going to tell us his story, beginning with the night of his birth, in Miami, during a devastating storm.

Moore’s opening, rhyming monologue suggests that we’ll be in familiar Dolemite territory, but with the exception of a few hallmarks, we will not be. The birthing scene that follows makes that very clear.

Petey’s mother, wracked with pain, is in her bed, calling out for a doctor who hasn’t yet arrived. She’s comically huge; when the doctor shows up, he asks if she’s pregnant with an elephant.

The scene feels like an isolated comedy skit, and that’s exactly how it plays out. The woman gives birth to a watermelon. Petey bites the doctor as he tries to deliver him. Petey emerges as what looks like a 10-year-old boy and beats up the doctor for spanking him. He then attacks his father for “stabbing” him every night in his sleep.

There’s a setup, then a mix of punchlines, visual gags, and physical comedy. The scene doesn’t last any longer than it needs to and it ends the moment it runs out of jokes. It’s exactly something you might see in a sketch comedy show — though it would have had to be a pretty daring one for the time — and we’re told everything we need to know about Petey Wheatstraw: You’re meant first and foremost to laugh. Don’t take anything too seriously. The film’s logic is its own.

All good lessons, but there’s one more you might not notice as easily. See, as overtly comic as the scene is, and as much of a comedian as this film’s leading man is, Moore doesn’t appear in this sequence.

There’s no reason he couldn’t. He could have easily played his own father. He could even have played Petey. (The boy is already not an infant at birth; he could just as easily have been birthed as a full-grown, smack-talking smartass with incredible facial hair.) Instead, Moore lets other people have the spotlight. He opens his best movie by letting others get all of the laughs, on their own.

We saw a bit of this disarming selflessness in Dolemite, and we’ll see much more of it here. Moore was becoming more comfortable handing the reins over to others, giving them longer spotlights, letting them share their own noble callings with whoever needed to see them. The best part, though, is that it never feels like we’re getting less Moore. Petey Wheatstraw is still a Rudy Ray Moore film, and we’re never more than a few minutes away from the man himself working his magic.

As Petey grows, he finds himself having to fight to survive in a rough neighborhood. That’s one of Moore’s hallmarks; I can’t say how much of it he might have drawn from his own life, but the idea of a community being willfully shitty clearly fascinated him. He had to be busted out of jail in Dolemite to restore order. Later in Petey Wheatstraw, our hero has his car torn apart by junkies. In Disco Godfather he…well, you’ll see.

Here, an old man sees a spunky but unskilled Petey lose a fight. He takes the boy on as a protégé and teaches him another Moore hallmark: kung-fu.

And this, silly as it may seem, is actually important. Moore did plenty of kung-fu in Dolemite and The Human Tornado, but it was clear that he had no idea what he was doing. Last week I pointed out that the fight scenes weren’t shot well, either, but I can’t fault director D’Urville Martin too much for that. Was it worth shooting them well? (The fantastic Dolemite is My Name, with Wesley Snipes as Martin, answers this with one of the film’s best jokes.)

At some point, perhaps gradually since his first film, Moore must have actually learned kung-fu. That’s not to say he’s any kind of master by the time of Petey Wheatstraw, but he’s improved noticeably. He’s studied it, practiced it, or at least taken a crash course in it, because he looks more competent and comfortable with it throughout.

As such, the cinematography rises to meet him. We’re no longer watching a comedian floundering his way through an action scene; we’re watching an action scene. Moore and writer/director Cliff Roquemore let us know up front that Petey has received martial arts training, not because it’s necessary to know but because it was worth drawing attention to just how much better at it Moore would be during this film.

When we catch up to Petey in his adult years, we find that he has indeed achieved his dream of being a much-loved comedian. Unlike Dolemite, he’s an insult comedian. This sets him apart to some degree from that character, as biting, spontaneous personal barbs are a much different artform from recitations of long, profane poetry, but I do admit it’s pretty funny to find out that Petey’s dream of making people happier is fulfilled by having him professionally insult them. I don’t think that’s an intentional joke on the part of the film, but it’s amusing anyway.

Petey is so accomplished in his craft that the mere fact that he schedules a show sends the owners of a rival club — another Moore staple — into a panic. This time it’s because Leroy and Skillet — a real-life comic duo Moore turns over several spotlights to — have taken a $100,000 investment from Mr. White. The idea was that they would use the money to book incredible acts during the down season, when they wouldn’t have any competition. As the only game in town and with acts worth seeing, they’d pack the house every night and make themselves and Mr. White a lot of money.

Then Petey Wheatstraw books a gig the very day after Leroy and Skillet are set to open, and this is a problem. Mr. White alluded to severe consequences if his investment didn’t pay off, and violence was likely the very least of these.

So far, so sedate. And to the credit of Leroy and Skillet, they do call Petey and ask him politely to delay his gig. Petey refuses to do so, which is understandable, but which also inspires his adversaries to take more drastic measures.

The pair hires a few goons to rough up Ted, one of Petey’s friends. Things don’t go quite as expected, as Ted’s kid brother Larry is there for the confrontation and refuses to leave. With the situation now overcomplicated, one of the goons pulls a gun on Ted.

Little Larry saves his big brother by taking the bullet instead. The thugs flee. The neighbors call an ambulance. Larry dies on the lawn.

It’s a dramatic scene which doesn’t quite seem to fit…and, hey, it doesn’t. I’ll admit that. But I do think the tonal shift is deliberate and important. This isn’t the graceless tonal whiplash of a Medea film; this is a comedy that is about to give its freewheeling hero a reason to get serious.

The death of Larry isn’t played for laughs, and Ted — played by Ted Clemmons — is legitimately emotional here.

The scene ends and the drama doesn’t let up. We see Larry’s casket being carried out of his funeral service. The boy’s grieving friends and family descend the church steps. It’s a powerful sequence. Everything here is grounded, real, and effective.

The thugs return. Sure, killing Larry sent a message, but it didn’t solve the central problem: Petey Wheatstraw is still in the way.

They open fire on Petey, striking him several times and hitting a number of mourners as well.

They drop the casket. Bodies fall. Others curl up and hope for the best, unable to take cover from this major tragedy as they were still processing another.

It’s real. It’s rough. That tonal shift was serious; it wasn’t one misjudged scene. It was deliberate, and now things are getting worse.

Then everything freezes. The dead, the dying, and the disoriented stop wherever they are. Clothing still ripples in the breeze, but nobody is moving or can move.

And a man strolls into frame.

He notices the devastation around him, is aware of what happened, but isn’t upset. He steps calmly around the bodies until he reaches Petey, who he restores to life. He offers Petey an opportunity to rewind time. To prevent this. To save himself and the people he loves.

It’s important that Petey makes his literal deal with The Devil over something like this and not, say, fame or fortune. We need to like Petey. We need to stay on his side, even as he does something as clearly foolish as shaking hands with the Father of Lies. Had Petey dabbled with darkness for his own gain, it would be pretty easy to dismiss anything that happened afterward as being well deserved. Instead, his bad decision becomes one that’s pretty damned understandable.

In that moment, wouldn’t you give anything to turn back the clock?

We’re eased back into the comedy, which is wise. This is not the time for a pie in the face; we’ll need to build back up to that. The man hands Petey a business card, which Petey reads.

“Lou Cypher?” asks Petey. “A small mistake on the part of the printer,” replies the man, masterfully undercutting the joke in a way that makes it much funnier.

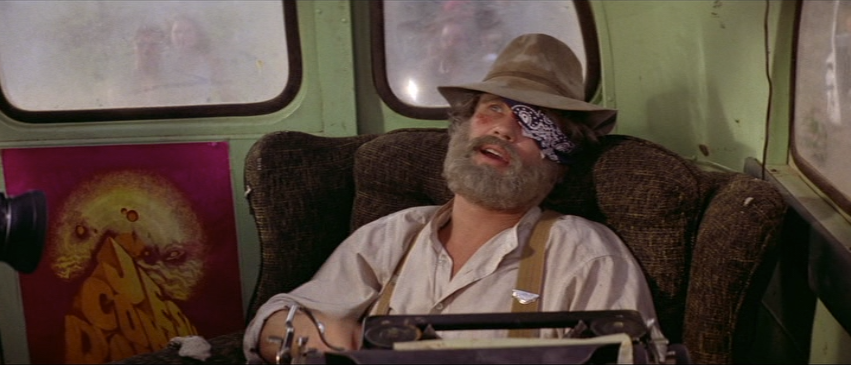

I do need to take a moment here to say just how much I love G. Tito Shaw in this role. He immediately became one of my all-time favorite portrayals of Satan on film. Shaw didn’t go on to do anything else; this is, at least, his only credit on IMDb, which seems positively criminal. He is a fantastic Satan, and he manages to be one without ever slipping into overdone territory.

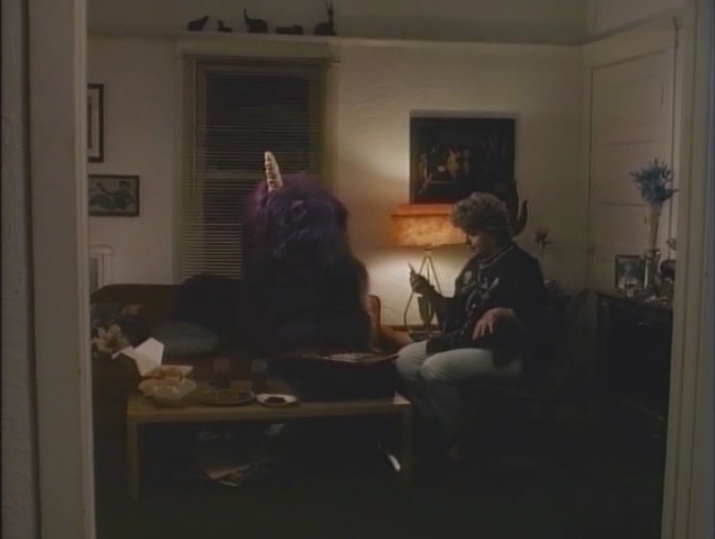

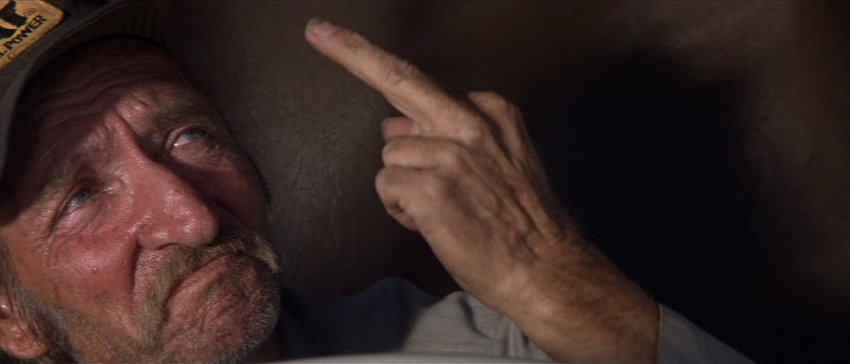

Shaw’s Satan is both affable and cold, shifting from one to the other in the space between two lines of dialogue. He’s a frightening presence when he wants to be, but as you can tell from the screengrabs he can’t rely on physical intimidation. Which is fine. He’s Satan. Satan isn’t scary because he can beat you up; Satan is scary because he can seal you into an eternity of torment.

And so Satan in this film doesn’t rely much on threats. He doesn’t need to. As much as threats might scare us, Petey Wheatstraw understands that the promises should be what keep us on edge. The kindly man with the grey beard does get visibly angry at a few points, but it’s all just theatrics. He’s at his most menacing when he’s acting the way he looks: gentle and collected.

I don’t know how much of the character Shaw brought to the role. I’d like to give him as much credit as possible, but I do get the sense a lot of it must have come from the writing. There’s a scene later in the story that consists of nothing other than Satan in a red tracksuit, jogging down the street on a sunny day. He’s all smiles. He waves at passersby. He is the embodiment of all that is evil and damn does that make him happy.

In exchange for rewinding time and letting Petey change his destiny, Satan requires that Petey marry his daughter. Petey responds that he absolutely will not marry The Dark Lord’s daughter. “That’s madness, man,” he says. “You’ve got to be sick.”

Then he realizes that he might be able to weasel out of it later, so he agrees.

Satan shows him a photo of his daughter and Petey responds again that he absolutely will not marry her with a brilliantly flat, “Oh, Hell no.”

Then, a second time, he convinces himself that he might be able to weasel out of it later. It’s a funny exchange with great comic timing on Petey’s repeated backtracking.

And so with no intention of keeping up his end of the bargain, Petey lives again. We see the events of the funeral a second time, but now reversed. Evidently Satan couldn’t rewind time far enough to resurrect poor Larry, but at worst that’s a plot hole that’s easy to ignore.

It’s easy to ignore because…

…take a deep breath…

It’s easy to ignore because for the rest of the film, Petey has a magical pimp cane.

If the idea of Rudy Ray Moore wielding a magical pimp cane doesn’t fill you with glee, I don’t think you and I can be of the same species.

From here, Petey Wheatstraw gets even stranger and becomes even more fun. It lives up to every ounce of the promise inherent in the concept, and Moore absolutely relishes it.

Petey obviously has some specific business he needs to tend to, and so does Ted. Together they confront the thugs who killed Larry, and later a disguised Petey attends opening night for Leroy and Skillet. Sure enough, the duo has a packed house, with Mr. and Mrs. White at the foot of the stage with their guests.

The house band plays a groovy, brass-heavy number to set the tone for the night of entertainment to follow. Leroy and Skillet appear on stage, soak in the applause, and launch into their comedy routine.

Petey — I am already enjoying this sentence and I’ve only started writing it — waves his magical pimp cane and controls their minds.

He makes the duo deliver his own kind of insult comedy at the expense of the Whites.

Leroy and Skillet — and the Whites, of course — are mortified and have no idea what’s happening.

They abandon their act and call out a singer instead. Petey again waves his magical pimp cane to make her lose her voice…as well as her wig and her dress.

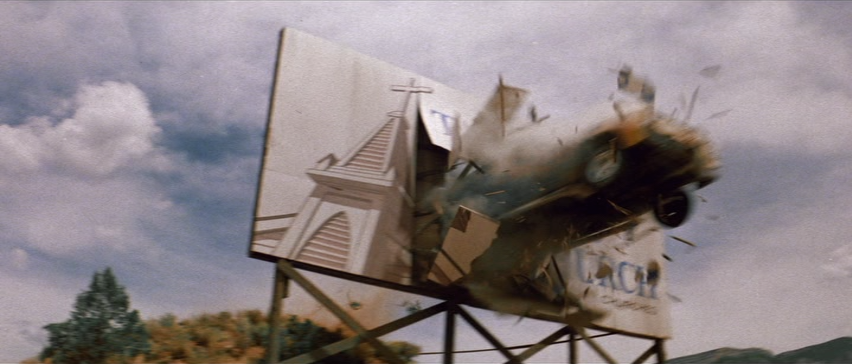

Something unexplainable is happening and the crowd becomes as distressed as Leroy and Skillet, which means it’s time for Petey’s grand finale: destroying the rival club.

He stands, waves his magical pimp cane, and brings the venue to a state of utter destruction. Thunder claps somewhere in the distance. Petey savors his revenge, and the film dwells just long enough on him standing there, alone in a destroyed theater, watching sparks rain down around him, that we see exactly how seduced he is by the power.

I don’t mean to oversell the gravity of the scene — there’s not much — but it’s impressive just how effective the sequence manages to be.

And then, of course, there’s comedy. Now that Petey knows what the magical pimp cane is capable of — erm…anything — there is so much more he can do with it. Leroy and Skillet are out of the picture. The thugs are dead. The cosmic balance has been zeroed out…which means Petey can now start the cosmos toward a net positive.

The montage that follows is fun, gorgeous, and infectious. It’s funny and heartwarming at once. Petey strolls through his dear, dirty neighborhood, and waves his magical pimp cane at anyone he can help. Why? Well, because they need help, and he can help them.

He stops a feuding couple before they slip into domestic violence. He gets somebody’s disabled vehicle running again. He saves a child who is nearly hit by a car. He sees a heavy woman stuck in a chair and, with a wave of his magical pimp cane, frees her by giving her the body we’re sure she’s always wanted. The song playing is a composition just for the film by Nat Dove called “Ghetto Street U.S.A.” It’s a fantastic and infectious tune, with a name reflecting the filthy streets upon which Petey strolls and a groove reflecting the better place he’s making it with every step.

And Petey just loves it.

The happiness on Petey’s face truly belongs to Moore. There is a genuine love for where his life has taken him. It works for the character, but works even better for the man playing him.

Both of them are just so damned lucky, aren’t they? They were somewhere, with some unfulfilled desires and dreams, and then, overnight, they were granted a power they never had before. The power to make things better. For themselves, sure, but also for others. And maybe it can’t last forever. Maybe the end is a hell of a lot closer than either of them thinks it could be.

But for now, in this moment, unable to conceive of something they can’t actually have, it must feel pretty great.

There are dedicated comedy moments involving the magical pimp cane, I should add; it’s not all good deeds. In one scene, the cane starts vibrating for no discernible reason. Petey lets it lead him like a dowsing rod to a small trash can in the club’s restroom, and then it stops. Inside is a bomb planted by the rival club owners.

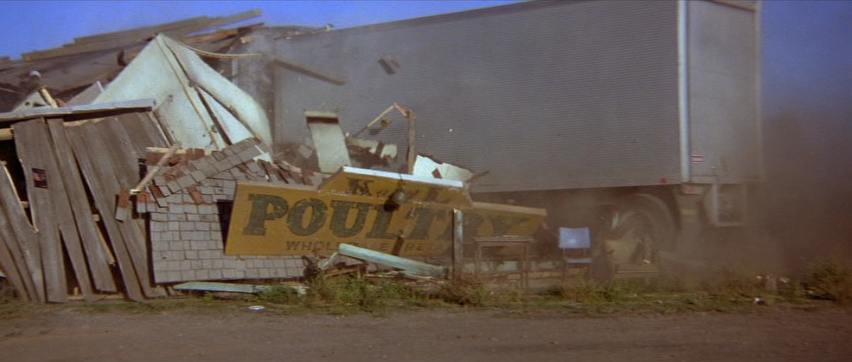

There’s some physical comedy as Petey & co. are in so much panic they can’t get the bomb out the door. They end up throwing it into the bed of a watermelon truck so that chunks of the fruit can rain down for blocks around.

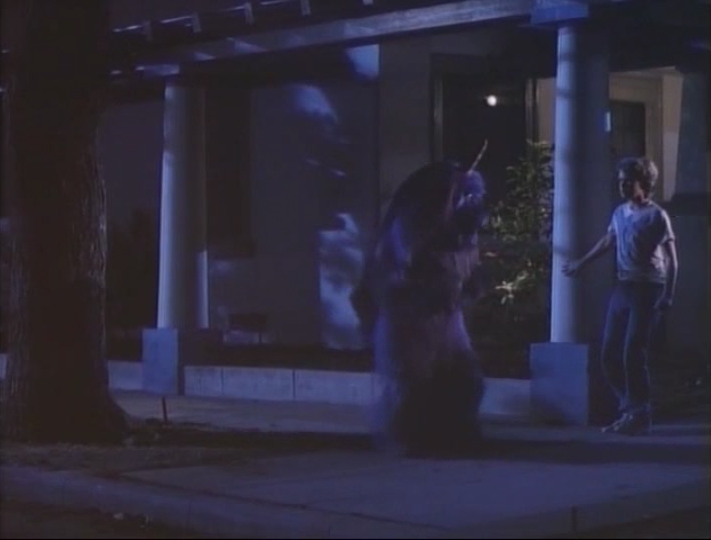

Petey uses the magical pimp cane frequently enough that Satan begins to wonder if the guy loves his magical pimp cane more than he loves the terrifying demon daughter of Hell.

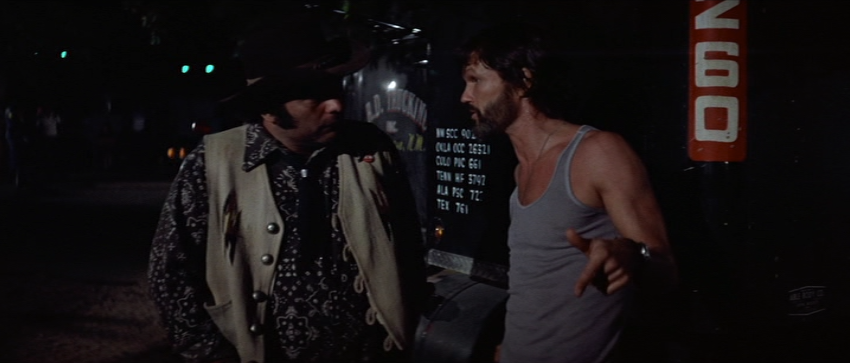

He confronts Petey on Earth to remind him of their deal, and to politely suggest that he not attempt to renege on it.

Satan lets him keep the magical pimp cane a little bit longer, which makes Petey even more confident he’ll be able to wriggle out of the agreement. As long as he’s got his magical pimp cane, after all, he’s able to fight back. He assures his friends — who question Petey’s wisdom in agreeing to marry Satan’s daughter — that he will solve the problem and keep them safe. None of them really seem to believe he can conquer the whole of Hell but, well, it’s not like they have any choice but to help him try.

This is where another difference between Petey and Dolemite is made clear. Dolemite is a natural hardass. He’s undefeatable. Someone may outthink him, but he’ll turn up in the end to rip their guts out with his bare fists. He is, as the sequel had it, a human tornado. A genuine, according-to-Hoyle force of nature.

Petey is the opposite. He absolutely fights well, but he never truly gets the upper hand until he has supernatural assistance. He can’t rely on brute force to solve his problems. Someone may beat the shit out of him, but he’ll turn up in the end to outwit them. Petey is more of an artful dodger.

So what does he do to outsmart Satan? He agrees to a time and place to meet The Devil and let himself be dragged to Hell.

…and then he kidnaps and drugs a hobo to take his place.

It’s a comedy, I know, but Petey Wheatstraw isn’t quite as good at painting its hero as flawed as it should be. Perhaps it’s just because Moore is that fucking likable.

In one scene he brushes a child’s hair and he does it too hard (or perhaps the kid’s hair got stuck in the comb) and the child starts crying. It’s not an act; it’s a kid expressing pain. And we still can’t dislike Moore, even as we watch him make a little boy cry.

Moore is a fun, loveable, charming son of a bitch, and while nobody will watch the scene and be glad he accidentally made a child weep, it’s also true that nobody will watch that scene and judge him for what happened.

And so when he kidnaps and drugs a hobo who can take his place in Hell…it’s something that in most movies would be a clear signal that our hero is either desperate or despicable. Or probably both. Here, it just causes us to detach; we know Moore is doing this because Moore thinks it’s funny. He’s still playing Petey, but we’re reminded that a comedian is making this movie and he’s taking us down what he hopes will be an amusing detour.

Once we know how things wrap up — the hobo wakes up in a car full of demons and gets away — it is indeed pretty funny! But Petey sure does creep into the territory of doing evil shit. He has one of his friends create a perfect replica of Petey’s face — where would we be without friends? — and they use it to disguise the sedated hobo.

In full fairness to our hero, he doesn’t expect his ruse to permanently fool The Devil; he just needs the hobo to take his place long enough for Petey and his friends to flee the city and start new lives somewhere else. It’s likely he expected the Devil to release the hobo once the trick was revealed.

Regardless, we’re thinking about it too much. Petey Wheatstraw gets away with us not believing its title character to be an asshole because its reality is fragile enough that we can pierce it at any point.

The Devil — being The Devil and all — is not amused. His demons storm Petey’s club and they ultimately kidnap Nell, played by Ebony Wright, Petey’s friend, assistant, confidant, and paramour.

Wright is great, and she’s another example of an actor to whom Moore is more than happy to cede the spotlight. A running joke in the film is that she apparently runs a phone sex service; Petey is staying temporarily at her house and she answers the phone with a smokey, seductive voice, dropping it the instant she realizes the calls are for him.

It’s funny, and Wright is a good enough actor that Nell comes across as well rounded and human. When she’s in the Devil’s grip, it’s believable that Petey would give himself up…or at least agree to a climactic rooftop showdown.

The Devil — as measured and calm as he’s always been in this film — keeps his end of the bargain once again. He does indeed let Nell go when Petey shows up. He’s a fair Prince of Darkness, which is probably what enables Petey to overpower him.

Still in possession of the magical pimp cane, Petey is able to fight back against the demons. Eventually, he even downs Satan himself.

He picks the old man up and drops him off the building, where he bursts into flames upon impact.

That’s it. Petey triumphs, because of course he does. He’s our hero, and good always defeats evil.

Except for the times that it doesn’t. This is one of those times. Petey climbs into the back of an idling car, thinking it’s his friends ready to start their new lives. Instead it’s Satan and his daughter, and that’s where we leave Petey Wheatstraw, in a freeze frame before he’s dragged directly to Hell.

It’s not a bad ending. It’s surprising enough that a comedy ended in failure for our hero, especially a failure that’s essentially played straight. I do wonder if — even only hypothetically — Moore and Roquemore had discussed a sequel. Leaving Petey here, suspended in this moment, would certainly leave the door open.

From the opening monologue of this film we know Petey is indeed in Hell looking back on what got him there, but that doesn’t mean a second film can’t see him trying to outwit The Devil yet again.

Having said that, I don’t think it’s our loss that Petey Wheatstraw doesn’t continue into another two or three or ten films. It gets to stand on its own as a one-off oddity that feels even more valuable because it only happened once.

For this brief stretch of 90 minutes or so, Moore reached the peak of his cinematic output. Maybe a sequel would have been better. Maybe it would have been exactly as good. Most likely it would have represented a step down. Probably a funny one, probably a creative one, but still a step down.

On its own, Petey Wheatstraw gets to stand as a solid achievement. Moore will always be known for Dolemite, and I’m not arguing that his legacy shouldn’t focus on that film and character. I will, however, argue that Petey Wheatstraw is long overdue for a serious critical reappraisal. Both Dolemite films had heart, but Petey Wheatstraw has soul. There’s very little to laugh at here, and plenty to laugh with.

It won’t change any lives, but it will make the people who see it happier, at least for 90 minutes. Moore waves his magical pimp cane and helps us all.

The spell may be temporary, but it’s a Hell of a lot of fun while it lasts.