You know, drilling down into this movie and really picking it apart several minutes at a time reveals to me just how magical it is. Sometimes the closer you examine something you love, the easier it is to spot its flaws. The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou, though, is a little different. It wears its flaws on its sleeve. You don’t have to dig to find them; they’re all in plain view. (And we’ll be discussing one of them today.)

The deeper I dig, I feel as though I’m only uncovering layers of beauty. As though its cracked, weathered exterior — like everything in Team Zissou’s arsenal, right down to the rickety foosball table we open on Pele and Ogata playing this week — is a design decision, hiding some deeper purpose. Or, at least, some deeper intention.

The care Anderson put into assembling this world is without equal, something easily measured in terms of the toll it took on the cast. Bill Murray at one point even said that if he didn’t get an Oscar for going through this, he’d kill the director. I’m paraphrasing because it’s been a while since I’ve read the exact quote, but I assure you it’s not off by much. And this comes from Bill Murray, who has likely been Anderson’s longest-standing, highest-profile champion.

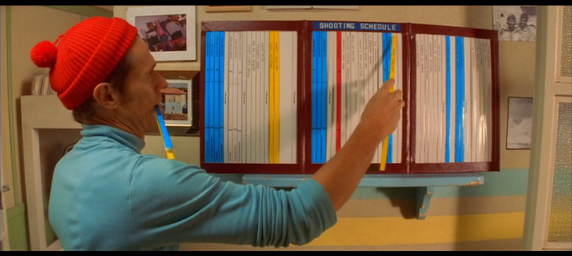

For a director who so often flits into comic fantasy, Anderson has an odd (though not unwelcome) obsession with things actually happening. That is to say that he may (in fact, does) employ Hollywood magic to create or enhance certain visuals, but in the larger scheme of things, he wants what he’s filming to be actually happening.

I’ll explain this by using a few examples. In The Darjeeling Limited, he actually rented out a rail line. Every scene in that film that takes place on the train — whether stationary or moving — was indeed shot on an actual train. The purpose? It’s hard to say, because whatever it was, it was in Anderson’s mind, and only he can tell us how successful he was in achieving it. But as easy as it is (and has been for around a century) to fake the motion of a train and to rear-project scenery, Anderson did it the hard way. Or…well…the real way.

There’s even a short scene late in that film that includes passing glimpses of characters in their isolated compartments. It would have been quite easy to stitch it all together in the editing booth, as none of these characters interact. And yet Anderson flew each of the actors, some of whom only appeared in one other scene in the movie, out to India to film them on the actual train. The purpose? Again, only he knows. But the appreciation it stirs in me is one I could not even begin to express.

“Does this look fake?” he seems to ask. And sometimes, even when it does, it isn’t.

Another, much smaller-scale, example came in Moonrise Kingdom. From the dotted-line progression of the main characters over a map to a child being struck by lightning to a climax involving a collapsing church, Anderson played with reality in that film…overtly, unmissably so. And yet when it came time for some Khaki Scout badges to fall into the water, Anderson insisted that they be dropped over and over again until they fell just right. He was informed — and knew — that whatever fall he was looking for could be accomplished easily in the edit suite. But he wanted them to actually drop.

Anderson’s connection to reality, as a director, is one of the most fascinating aspects of his films. And it’s one that I’m not quite sure I fully understand. It’s a richer discussion more than it is a solid conclusion, I think.

Which, let’s be honest, more or less sums up his oeuvre. And I’m very grateful for that.

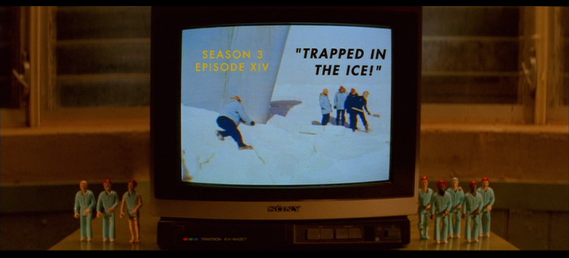

We pan over to another part of the room where much of the rest of Team Zissou is watching an old documentary of Steve’s. It’s not easy to figure out how long ago this was meant to be, but the hairstyles — and, in Steve’s case, the hair color — are clue enough that we’re supposed to see this as a different era…whatever an actual calendar would have to say about that.

Ned is still bundled up from his dip in the water (sipping a hot beverage in contrast to Klaus’s beer) and there’s something unspeakably sad about these people watching themselves on television in complete silence. Klaus’s “That’s what it used to be like” is heartbreaking when you take into account that, in all aspects other than mood, that’s how it still is.

Steve’s production values haven’t increased at all. His most recent film, as of this scene, is the Jaguar Shark expedition that opened The Life Aquatic. This obviously older film suggests that neither Steve nor his crew have learned anything about how to make a movie. The staged chumminess, the scene of Steve recognizing a “distress bark” that was clearly filmed later, the high-school filmstrip soundtrack…Steve’s gotten older, but he hasn’t gotten any more competent.

What’s even sadder is that there’s no way to know whether Klaus (or anybody else) is remembering this accurately. On the screen, everyone’s laughing and having fun, unwinding and then working together to coordinate a rescue of a wild snow mongoose and her pups. But that’s clearly not how it actually happened. In fact, it’s doubtful that much of this footage is genuine; it’s all marred by the too-deliberate line deliveries and too-perfect framing that scream “reenactment.”

Klaus and the others are reflecting back on happier times. That’s sad enough. But the fact that those happier times may only have existed on film, after significant editing, is sadder still.

Of course, I keep saying “film.” The SEASON 3 caption suggests that this might have been from an otherwise unmentioned Steve Zissou television program. Again, it’s impossible to know for sure. We’re not told, and it’s not completely unlikely that Steve’s films are collected into larger “seasons” based on their subject matter.

It’s also possible that these aren’t actual seasons / episodes in the standard television sense; they could have been shot or edited in this way to serve as educational materials in public schools. (I recall a similar program, The Voyage of the Mimi, from my own grade school days.)

Of course, the real reason I wanted to take a screen grab is to show off these incredible Team Zissou action figures.

I’ve actually discussed this with a friend of mine. Anderson’s characters would make perfect action figures. They each favor a uniform of some kind, they each have their own sets of accoutrements and talismans (talismen?), and even when they’re played by the same actors we’ve seen in other roles, they’re each visually distinct. I’m picturing a line of very lifelike (as Ned might say) McFarlane Toys, but as we see here, these cheap little GI Joe-style figures would be just fine. So fine that I’m getting angry that I don’t already have them…

The arrangement of the figures — as with the arrangement of everything else in the film — is quite deliberate. On the left we have Esteban, Steve, and Klaus. We’ll officially learn the significance of that in the middle of a lightning strike rescue op., but we already know how Klaus views his relationship with Steve, and it’s not much of a logical leap to assume that he feels (felt…) something similar toward Steve’s closest confidant.

On the right we have a grouping of less significance, I think. It’s what Gilligan’s Island might refer to as “the rest.” From left to right, that group contains Ogata, Vikram, Pietro, Pele, and Wolodarsky. Based on this and on what we see in “Trapped in the Ice!”, the makeup of Team Zissou hasn’t changed in some time. (Again, at least an “era” in Zissou time.) Perhaps equivalents of Anne-Marie and the interns came and went, but the core team remained unchanged.

Until Esteban’s death, of course. Thanks for bringing that up.

After the film, we see that Ogata and Pele have joined the rest of the group in watching their old adventure. They, too, are still and silent. Seeing these happier times — however real or false they may have been — has a sobering effect on the group. Especially when you consider that Klaus must be saying “That’s what it used to be like” for Ned’s benefit. It has to be Ned — with whom he otherwise clashes — because everyone else in that room was there.

The past is comforting to them. It’s where they were happy. Or, at least, they’re willing to believe that. Team Zissou doesn’t sail bravely into new sunsets; it bobs in place, remembering all the films that made it seem like they were going somewhere.

That moment ends with a nice reprise of what happened in the Explorers Club when people were gossiping about Steve: the camera pans to find him standing there. The blocking is even better this time around, with the Zissou pinball machine right next to him. It’s a relic of his past success, a faint (and fading) glow in a dark room, a reminder of a time before companies started terminating his licensing contracts. An idealized cartoon on its faceplate…a representation of the real thing, frozen in time, not subject to downfall, but also going nowhere.

Seeing Steve standing next to it is a very funny image, though one I can’t say I’ve ever laughed at. It’s a clear reminder of how far he’s fallen. Look at him as he stands in that doorway. Would anybody make a pinball machine to celebrate that man today?

In his action figures and sneakers and pinball machines and goodness knows what else, Steve was pretending to be somebody…but he was only given the opportunity to pretend to be somebody because he was somebody. He did earn his legacy; the problem is that at some undefined point in the past, he became complacent. The legend was built…so what was left to aspire to?

Any number of answers could be valid. But Steve had, and has, none.

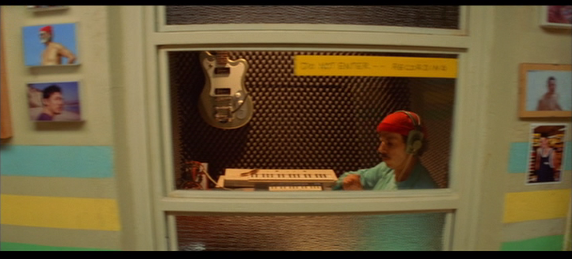

Cue a haunting, acoustic, Portuguese version of “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide.”

It’s a great performance on its own, but as a cover version of Bowie’s original, I’m not totally convinced. It never “sounded” the same, for lack of a better way to phrase that. It felt much more like a song inspired by “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide” than a performance of it. I may be in the minority, however; I once watched the film with a good friend of mine and she recognized the song right away.

Steve says nothing to his teammates (so much for teamsmanship), and walks into the room he shares with Eleanor. He’s beaten, and Eleanor asks (beautifully, perfectly, from down the hallway), “Had Ned’s heart stopped beating before you pulled him out of the water?”

Our hero steps out of frame before she asks, but steps back into frame to repeat the question back for her. He repeats every word of the question, as though looking for even the smallest loophole to get out of this discussion. Eleanor’s very careful — and humorously elaborate — phrasing is very likely due to the fact that Steve’s tried to wriggle out of an awful lot of things in the past.

When he realizes he has nothing left but to answer honestly, we find out that, yes, Ned’s heart had stopped beating. But they “got him started again pretty quickly,” which is the kind of reassurance that only makes the problem more horrifying.

The conversation continues, but much later, it seems. Eleanor is now in bed, rather than in a chair down the hall. Anderson implies a long, awkward silence without showing us, and I adore that.

She’s thought about what she’s going to say, and what she says is, “Don’t go on this voyage right now, Steve. One of you is already dead, after all.”

Eleanor has picked up on the foreshadowing that Steve — possibly deliberately — is overlooking. On the DVD there’s a deleted scene of Eleanor warning Ned about going on the voyage as well. As our “Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come” Eleanor has foreknowledge that could change the course of events. Of course, living with Steve as long as she has, “foreknowledge” is less like prediction and more like the simple process of elimination. (No pun intended.)

It takes Steve a moment to realize that she’s referring to Esteban, and we have our answer to a question asked much earlier: why isn’t Steve “sitting shivah?” Because he’s already forgotten. And as many times as he’s reminded, he’ll forget again.

Steve doesn’t mourn. As close as we’re told he was to Esteban, he does not acknowledge (or process, or react to) the man’s death. He projects the responsibility onto the Jaguar Shark — and enacts a vague scheme of “revenge” — but forgets Esteban himself.

Steve Zissou is very much the opposite of Chas Tenenbaum in this regard. Whereas the unforeseeable and unpreventable death of someone important to Chas resulted in a heightened, tense, hyper-careful lifestyle, Steve lost his closest friend and crewman to negligence…and would prefer not to think about it. In fact, he gets upset if he is made to think about it, as he is here.

His tremendously dickish, “Thanks for bringing that up,” sets the rightful tone for Eleanor to stub out her cigarette and abandon the team. She is, after all, the only one who seems to be taking the inherent tragedy of Team Zissou seriously, and her words of caution to him represent the best she can do to stop this from happening again.

If she goes unheeded — if her visions of the future are dismissed — then she can serve no purpose. She leaves Team Zissou. And as much as I love Steve…good for her.

She explains that she doesn’t want to be a part of whatever is going to happen out there, knowing full well that if Steve is the kind of man who will be so dismissive of his own crewman’s death, there’s no chance of this turning out well. As we in the audience know, she’s right.

Steve replies, “Nobody knows what’s going to happen. And then we film it. That’s the whole concept.” Wolodarsky adds, “That’s how we’ve always done it.”

But by this point, as we’ve seen and as we’ll see again later, we know that isn’t true. Continuity is slaved over, ADR is frequent. Reenactments and staged scenes are commonplace to the point that we don’t know how much of Steve’s footage (very much unlike Anderson’s) is real. In fact, as Steve pleads with her not to leave, he reveals that she’s the one who would tell him “the Latin names of all the fish.” This makes a certain moment in “Trapped in the Ice!” play differently in retrospect. When Steve is asked what kind of animal they’ve found, the camera doesn’t pan to him; we cut to him. Very likely, he didn’t know. Eleanor telling him was either snipped out, or the scene was reshot later after Steve had the chance to ask.

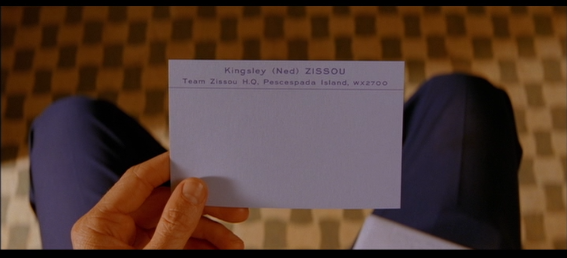

Eleanor expresses disapproval that Steve took Ned’s money to bankroll this film, and Steve, evading the actual concern, refers to Ned as “an investor…he’s my sidekick.” At no point does he say son, which I think is important. Steve only plays that card when it will do him some good.

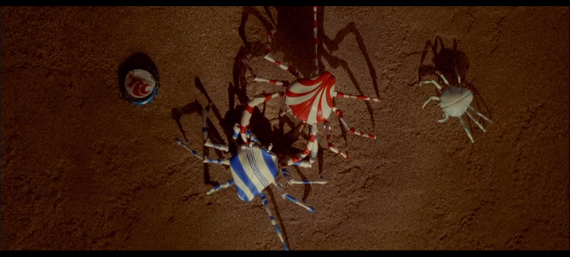

Then Steve indicates, just as Eleanor steps out of shot and onto the pier, that the sugar crabs are back. He’s told — again, he doesn’t know — that they’re mating. And this is one of my least favorite moments in the film.

The sugar crabs themselves have a nice design, and I love that there’s a third role played in the mating ritual. That’s an interesting and welcome flourish. But, beyond that, it’s a bit too pat. Steve is fighting with his wife, he’s told explicitly that they’re witnessing mating, and the female yanks the male’s arm off and leaves.

Anderson is typically above being so overt in his symbolism. It’s really something, I feel, that should have either been cut, or re-staged so that the male-being-left-wounded aspect was portrayed more artfully.

It takes me out of the film in a way that so many other moments of silliness do not. (See the swamp leeches scene later in the film.) Broad comedy isn’t necessarily a bad thing in an otherwise sedate atmosphere, but in this case, I think it becomes too much of a cartoon and works against something Anderson was otherwise doing a great job of establishing cleverly.

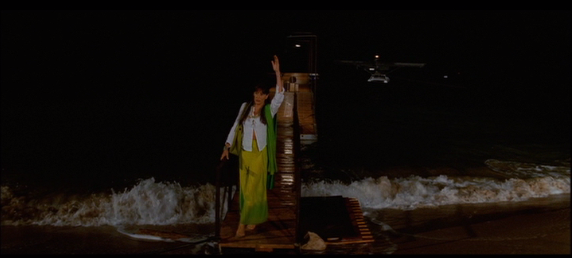

Eleanor says goodbye, but Steve doesn’t like that phrase. Steve retreats back into the same comfort zone we encountered in his interview with Jane. Favorite color, blue. Favorite food, sardines. Favorite ways of saying goodbye? Bon voyage.

It may not seem like much of a departure from “goodbye,” but, taken literally, it’s a wish for a “good journey.” Eleanor allows the substitution, and indeed does wish Steve a good journey.

It’s what she wants, which is why she says it.

But she already knows how it will turn out, which is why she won’t be around for it.

Next: The Belafonte at sea.