I love video games. For nearly all of my life, I’ve loved video games. Some of my earliest memories — and a huge portion of my fond earliest memories — involve video games.

I remember playing a skiing game on Atari with some friends at one of my birthday parties. We’d hand the joystick around and love every second of a game that was probably embarrassingly simple and still too hard for us to play properly.

I remember playing another Atari game with my uncle. I forget what it was called, but you each controlled a cowboy on a different side of the screen and you had to shoot each other while obstacles scrolled by. Only I didn’t want to play it that way. If you shot an obstacle, part of it disappeared, pixel by pixel. I wanted my uncle to help me shoot the stage coach that roamed vertically across the center of the screen until it was completely gone. I remember that being fun.

And I remember later, when we had an NES. My mother would come into the room I shared with my brother to play Super Mario Bros. To this day, it’s the only time I’ve known her to take an interest in video games, and this was a strong interest. Controlling a springy little plumber through colorful levels of endless surprises triggered something in her that no other game did. I can’t blame her. Super Mario Bros. did that for a lot of people.

I’ve been playing off and on ever since. I stopped for a few years in college, almost entirely, because I had two jobs and a full class schedule. There wasn’t much room for me to do anything aside from read for class, study for class, and embarrass myself in front of women. I was very busy.

Otherwise, though, I’ve been playing video games regularly. Games of all genres. All lengths. All skill levels. And to this day, if I’m asked what my favorite game series is, I’ll give the same answer I gave when I was seven or eight, whenever I played it for the first time: Mega Man.

I adore Mega Man. When I posted to this site’s Facebook page that I was considering doing a retrospective on the games, I got a good deal of engagement and encouragement. I don’t think that’s because anyone expected me to be especially critical of the games; people know how much I love Mega Man. How much I love playing the series. How much I love perfecting the series. There’s something in these incredibly simple games about a little boy in blue pajamas fighting evil robots that brings me back in ways that other games — including many games I’d call great — just don’t.

The Zelda series is bigger. The Mario series offers more variety. Just about any other game in existence offers a better story. (Mega Man stories are, without fail, “Go kill those things.”)

But on some level I must not care too much about any of that, because it’s Mega Man that has my heart. It’s Mega Man I play to unwind. It’s Mega Man that reminds me exactly how much fun gaming can — and should — be.

I’m pretty sure I played Mega Man, the first game in the series, first. It’s possible I started with Mega Man 2, especially since Mega Man didn’t set the world on fire the way its far superior sequel did.

Whenever I played it, though, I played the hell out of it.

I never owned Mega Man. I think one of my friends might have, but I know for sure that it was a frequent rental for us at the video store. It won us over for what’s probably its best-known gimmick today: the opportunity to play the stages in any sequence you like.

This was a design decision that I’m sure had nothing to do with video game rentals, but it sure worked out well for us.

Normally we’d rent games for a weekend and gamble on whether or not we’d enjoy them. The box art would call out to us and suggest worlds of adventure within, but rarely was the experience anything like what we felt was promised. We’d play plenty of games and be disappointed. Or — arguably worse — we’d play games that weren’t disappointing, but struggle to get past the first two or three stages.

I say that may have been worse because when it came to games we didn’t like, we didn’t really care how much we did or didn’t get to see. With games we enjoyed, though, the difficulty could be a real turnoff. We’d have a few hours over the course of a couple of days to get as far as we could. If we couldn’t get far — and if the game didn’t have a password system — that was it. And we’d likely never rent it again, because the one memory that lingered most firmly was that of some roadblock we couldn’t make it past.

Mega Man felt like a miraculous gift in that regard. Yes, it was punishing. No, we never made much progress. But the fact that we could actually see all of the levels…the fact that we could experience all of the levels…the fact that the game — the entire game! — was right there, letting us play it…well, we fell in love. My friends and I rented Mega Man over and over again. And we were never disappointed.

Other games felt like getting to explore a huge sandbox a few feet at a time. Fail to overcome some challenge or puzzle and that was it; you were stuck scratching around the same corner. Mega Man pulled out all of the boundaries and said, “Here. Have fun.”

We did.

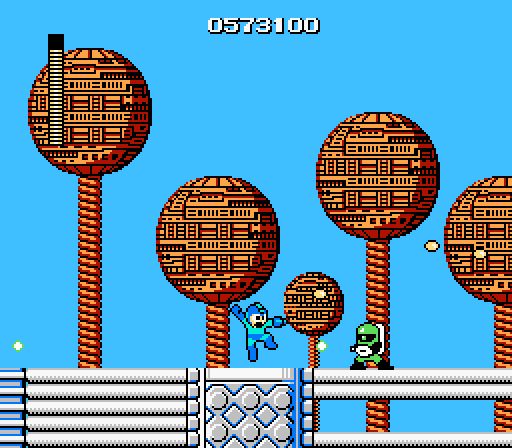

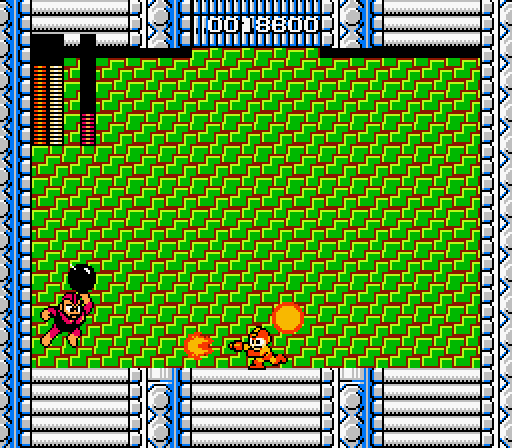

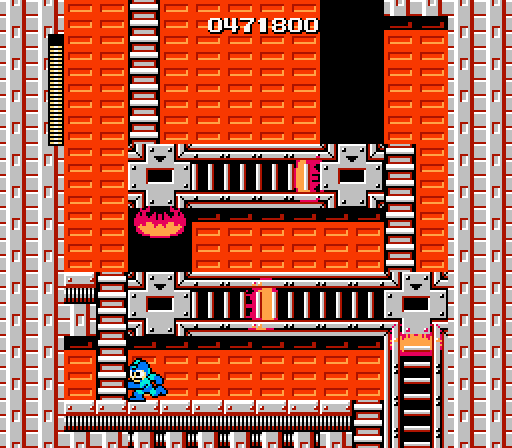

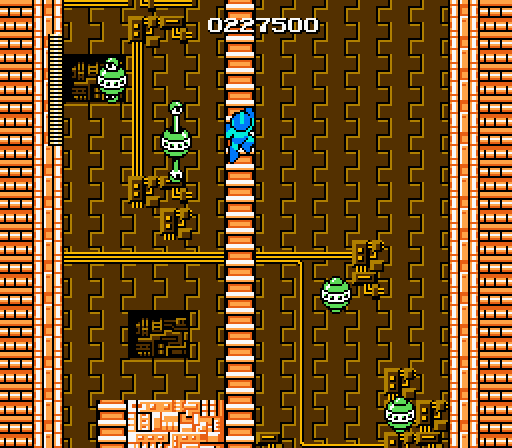

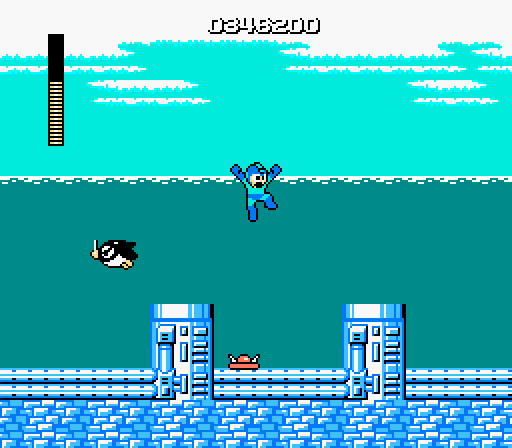

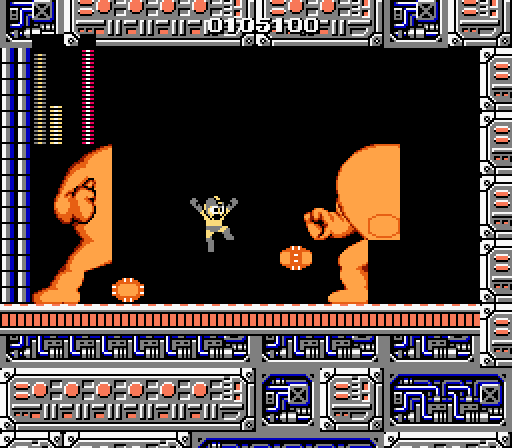

Mega Man felt different from most other games. It stood out. On a less tangible level, I think it was just the feel of the game. The way it evoked — though none of us would have been able to articulate this at our young age — a comic book or a Saturday morning cartoon. It was all thick lines and bright colors…enemies with big, goofy googly eyes…varied environments suggesting the kinds of weekly adventures heroes would undertake in other media. We were drawn to it the same way we were drawn to certain TV shows or films…only this time we were playing it. It was a way to immerse ourselves in worlds we previously could only enjoy from afar, from the safety of our couches or bedroom floors. In Mega Man there was no such distance, and we were not safe. We died. A lot.

Here’s another one of my favorite early video game memories: a friend on my block said he could beat Mega Man. Nobody believed him. Why would we? It was a preposterous claim. Nobody could beat Mega Man.

We assembled at his house that afternoon. He picked up the controller, and we all crowded around him to watch.

He took unnecessary damage, I’m sure. He died plenty. He handled dangerous situations in idiotic ways. He probably cursed a bit. Hours passed. Maybe five or six hours. But we were riveted, because he kept making progress. And eventually…he really did beat Mega Man. Probably after a dozen continues and fifty or more deaths, sure, but he beat Mega Man.

We couldn’t believe it. I still can’t.

Today, of course, I can visit Youtube and call up hundreds of videos of people beating Mega Man. Without dying, without taking damage, without using special weapons. Speedrunning. Exploiting clever glitches. Playing Mega Man — a game I know better than I know most things in life — in ways I never would have imagined possible. I can watch World Record runs. I can watch players so graceful that their movements are like beautiful choreography. I can watch players so good at the game that they can narrate interesting facts and details as they play, never missing a beat.

But, somehow, it was still more impressive to me to watch my friend beat it in his bedroom that day.

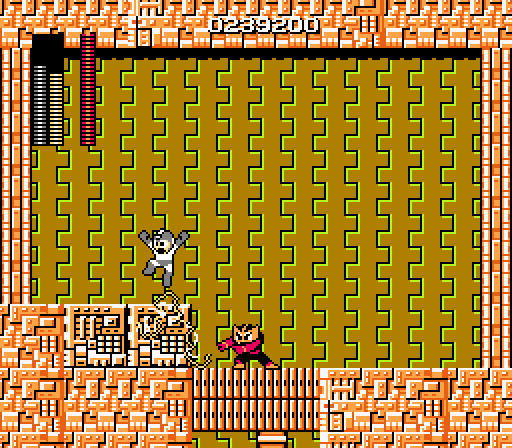

There’s no comparison in terms of skill. My friend sucked. But he sucked less and less each time until, finally, he was able to eke out a victory. Our hearts were in our throats during that final fight against Dr. Wily. In fact, I’m sure it was the first time many of us had seen Dr. Wily. Or his stages, for that matter.

But he beat it. And we screamed and cheered. And I miss that.

I miss that communal joy that came from overpowering some challenging video game. I miss that feeling of discovery when we sussed out a difficult puzzle. I miss that feeling of elation when we found a false wall or a hidden powerup or some other secret, tucked away from the visible world. I miss that a lot. While the internet has made games so much easier to find and play and distribute, it’s made it harder to believe they matter. Back then, every victory was earned through sore thumbs and thrown controllers and profanity and teamwork. Today, I can look up a walkthrough. I can force my way through difficult areas with save states. And if I get lazy, I can just look up the ending and watch it on the video streaming site of my choice.

I almost never do those things, though. Because that’s not gaming to me. Gaming, to me, is what happened in my friend’s bedroom somewhere around thirty years ago, when a group of kids were glued to the screen, shouting advice, hoping against hope that the kid with the controller in his hand was actually going to do what he said he could do.

Am I romanticizing it a bit? Maybe. And while I’m going to romanticize Mega Man as well, I’ll admit that it’s not without its flaws. But there is a real, honest, genuine love I feel for the game, and to understand that love, I think we need to look at its place in history.

Mega Man was released in 1987. Again, I have no way of knowing when I first played it, but the game was released in only the third year of the NES’s life. Prior to Mega Man, nearly all of the games on the system were simple sports titles, uninspired platformers, or single-screen score attacks that hadn’t much evolved from the much more primitive consoles that came before.

Mega Man stood out, and it stood out sharply. Looking back at a list of NES releases, only a handful of games prior to Mega Man would I consider “must owns.” Super Mario Bros., Castlevania, Metroid, The Legend of Zelda, and Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out!!. If I’m feeling generous, I’ll toss Balloon Fight in there.

But that was it. The rest of the games were fairly forgettable. They might be fun to play — and let’s never discount the value of fun — but they didn’t…matter.

Mega Man mattered. It brought its own ideas to the table, and it set a precedent for quality that later games either did or didn’t live up to. And if they didn’t…well, we’d just rent Mega Man again.

That list of games above, I think, is important, because it doesn’t just represent the early greats on the NES; it’s a list of games that expanded upon, pushed the boundaries of, and defined entire genres.

Super Mario Bros., for example, became the immediate template for platformers. It defined the feel and the flow of the action. It cemented specific expectations of difficulty…how to be incredibly challenging without ever being “unfair.” It struck gold with its catchy, evocative music that singlehandedly rid the world of blips and beeps as viable soundtrack options.

I won’t go through each of the games — this is about Mega Man, after all, and I’m sure you know what each of them did to redefine gaming as we now know it — but Mega Man deserves a place on that list for its own irresistible ideas. We’ve already discussed the fact that you can complete the main stages in any order, but there’s also the series-defining choice of having Mega Man inherit the weapons of defeated bosses.

This was both a great bonus in itself, and an answer to one of the challenges of designing the game in the first place. After all, if you’re going to let your players complete stages in the sequence of their choosing, how do you define progression?

That’s how you define progression.

You reward them with a new toy. A toy that allows them to conquer future challenges in unexpected ways. A toy that changes the way they’re playing.

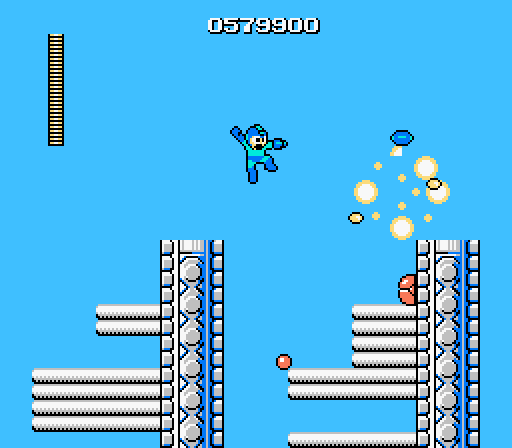

The weapons system in Mega Man did a great job of making the NES itself feel massive and versatile. Sure, the controller only had a couple of buttons (A and B, which we all referred to as Jump and Shoot), but Mega Man let those buttons control seven weapons and a utility. That’s eight things to play with when most games gave you one or two. The Legend of Zelda and Metroid both found ways to cram relatively large arsenals into the same constraints, but it was Mega Man that did it best and the most impressively.

…in theory.

In practice, let’s be honest: a good deal of these weapons are terrible.

The Rolling Cutter is a lot of fun — serving essentially as a very powerful boomerang — and the Thunder Beam has a wide range, enormous power, and low energy consumption. So far, so good.

Then you get the Ice Slasher, which only actually harms one enemy in the game: Fire Man, who is more easily defeated with your default Mega Buster anyway. It freezes enemies in place, which is nice, but is really only useful against the powerful Big Eyes…and even then you just freeze them in the air and run underneath them. Hardly thrilling stuff.

I have a soft spot for the Fire Storm, which surrounds Mega Man with a very temporary shield as it shoots a single projectile forward, but I’d be lying if I said it was anything impressive or even, in most cases, worth using.

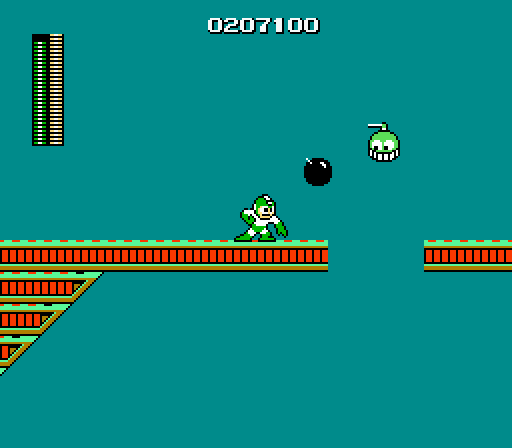

At the bottom of the heap, though, are the two truly lousy weapons. The Hyper Bomb is initially pretty cool (I admit that I still love seeing Mega Man pull out a big, black cartoon explosive), but its frustrating delay makes it almost pointless; just about any enemy you could hit with it will move out of the way long before it explodes. This is a shame, because it should be a great weapon for those enemies who are too short for Mega Man to hit with his Buster.

And, of course, there’s the Super Arm…which one of my friends refers to as “Guts Man’s worthless thing.” I can’t really correct him. It’s entirely dependent on finding ammunition on the screen (big blocks that Mega Man can lift and hurl), and removing certain barricades — its one actual use — is faster and more easily achieved by using the far superior Thunder Beam anyway. You had one job, Super Arm…

Of course, Mega Man was just finding its footing. It wasn’t going to have a wealth of great weapons right off the bat; it was forging new ground. Having any special weapons was a bonus to players at that time. It’s really only with the benefit of hindsight (hindsight introduced by this game’s very first sequel) that the flaws in Mega Man stand out to any significant degree.

Playing it now…yeah. It’s a bit rough around the edges. In fact, I’m sure that it turns people off when they try it for the first time. Mega Man was a standout title in its day, but now…well, it still has its charm and its obviously huge ambitions, but it probably doesn’t offer much else.

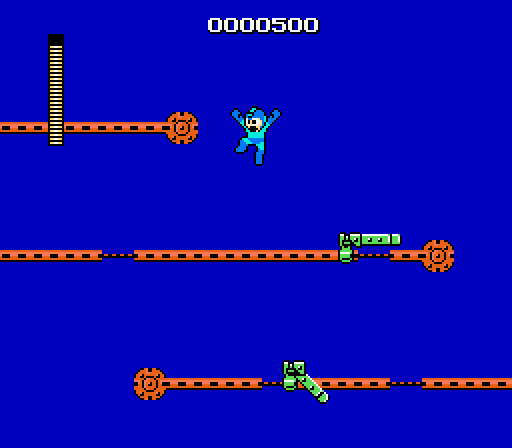

For starters, the game struggles and chugs constantly, as though its code is just barely holding itself together when there are more than a few moving sprites on screen. (This is probably true.) Mega Man himself controls in a strangely slippery manner, taking a few frames to stop moving after you lift your thumb off the D-pad. In a game that often demands precision, this is inexcusable, and most times that I play Mega Man now I go in knowing that I’ll take a lot of damage from obstacles that it’s more or less a crapshoot to avoid.

Then there’s the stage design, which is…a bit uninspired. In 1987 the NES was already home to a host of forgettable, bland platformers, and Mega Man, at times, is no better or more carefully designed than those were. It often suffers from the belief that throwing some enemies and spikes together makes a stage. Technically it probably does, but rarely does it feel like the product of anyone with a clear idea of what they want to do.

As such, I’m surprised each time I play Mega Man, simply because so much of the game is not memorable.

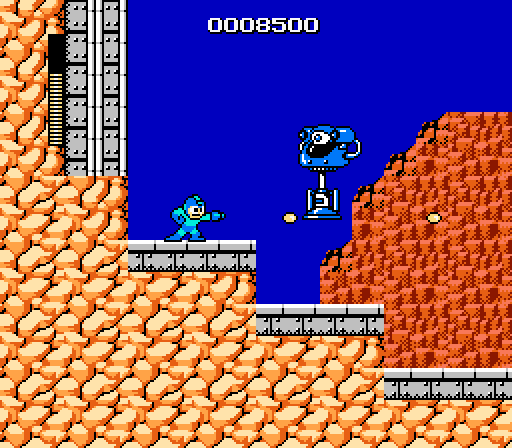

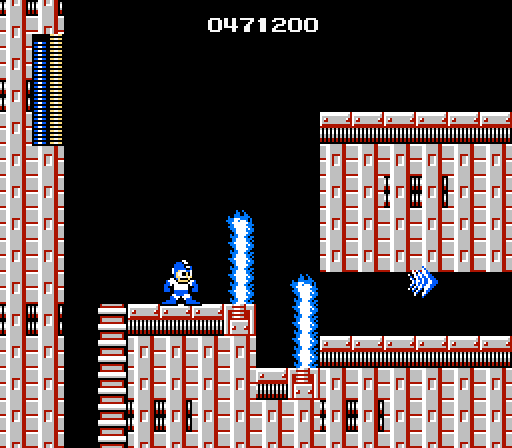

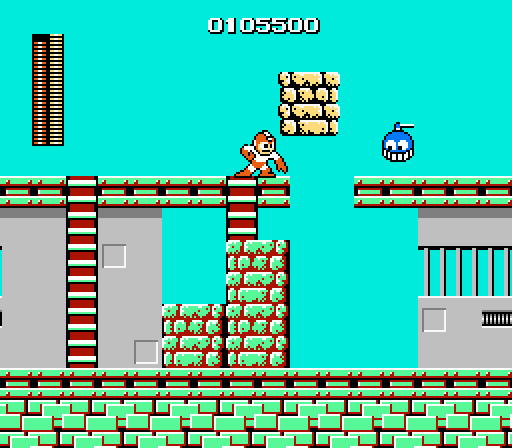

I’ll go to bat for certain stages, which actually do seem like they were designed with some kind of logical progression in mind. The best example of this is probably Cut Man’s, which begins with some simple jumps and ladders to let players learn the basics of the controls, adds in some simple enemies that can be defeated with a single shot, and then gradually introduces more complex ideas. We move on to the enemies that shield themselves at regular intervals, for example. We toss in some others that can only be shot while they’re hopping, because they’re too close to the ground to be hit otherwise. We start combining enemies with (relatively) tricky jumps. We introduce a flying enemy that shoots in multiple directions, and force a player to navigate ladders while dealing with it. Then we meet Big Eye, the game’s designated and recurring bruiser, and finally the boss himself, who is designed to challenge our ability to jump, shoot, avoid projectiles, and navigate obstacles at the same time. It’s the final exam at the end of a fairly well constructed course, and I appreciate that.

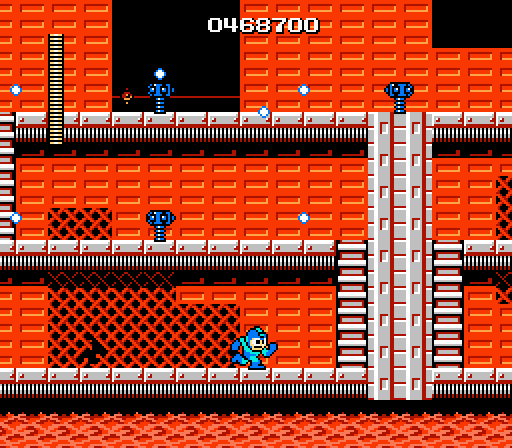

Bomb Man’s stage follows a similar sort of progression, and I’ll go to bat for that one, as well. Elec Man’s doesn’t — at least not to the same, impressive degree — and its favorite trick is to throw difficult-to-avoid enemies at you almost as soon as you enter a screen. (Not to mention those tiny crawling enemies that patrol platforms and are far more challenging than they ever are fun.)

But Elec Man’s stage actually has the best sense of implied progression, as you climb almost without pause to the very top of his tower, where the man (or Man) himself is holed away, generating power. You begin the stage at the base of the tower where the walls are a murky greenish color; when you reach Elec Man’s boss room, those same tiles are now a vivid and bright yellow. The suggestion, deliberate or not, is that the strength of the lighting changes with your proximity to the guy powering it.

That’s pretty cool.

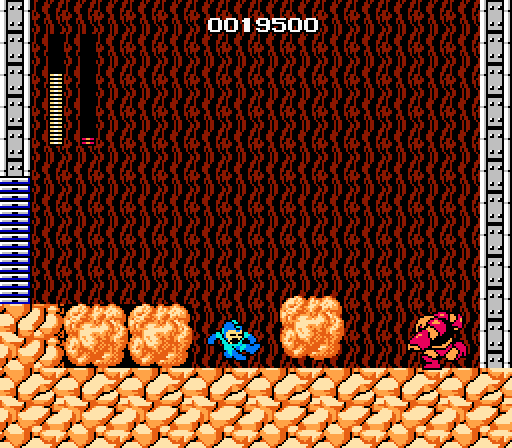

But then you have stages like Fire Man’s, which is just a series of unfair traps and enemies raining down upon your head. Then there’s Ice Man’s, which is just sort of there and contains the two most frustrating passages in the game: the disappearing blocks and the much-too-long journey over bottomless pits atop glitchy enemies who shoot at you and move in literally random patterns…sometimes making it a genuine impossibility to clear.

Guts Man’s stage fares little better; it’s just a handful of screens long, and it actually seems to give up on itself before it can even decide what it wants to be. The same can be said for Guts Man’s theme tune, which is oddly abbreviated compared to most of the other songs in the game.

On the whole, though, Mega Man deserves major and serious recognition for its music.

The one-two punch of Super Mario Bros. and The Legend of Zelda defined soundtracks for the rest of video game history. (Composer Koji Kondo wrote the music for both of those games, and as far as I’m concerned he’s one of the most important composers of our time.) Compare the sunny, peppy overworld music of Super Mario Bros. to The Legend of Zelda‘s more adventurous, compelling, driving equivalent. One feels carefree and light…the other weighty and significant. Then compare their underworld tracks; Super Mario Bros. feels damp and stuffy, in line with the muted blue color palette used in those areas, while The Legend of Zelda swirls and disorients, foretelling danger and encouraging wariness.

Video game tracks from that point forward were held to a certain standard; they didn’t just need to be catchy or cute…they needed to be evocative. They needed to not only fit the area, but fit the mood. They became an important and defining part of gaming in general. Not many games prior to Mega Man took that to heart, and it’s a challenge this series has always at least tried to meet.

Even in this first game’s comparatively weak and simple soundtrack, it’s easy to see how deliberate it is. Fire Man’s track feels like the spicy, faux-Latin tune you should hear in a metal corridor with lava underfoot and fire falling from above. Ice Man’s track is halting and chilly. Guts Man’s isn’t great, but it feels mechanical, shuddering, and stubborn, in line with the robot-operated quarry that it underscores. Elec Man’s is probably the best, feeling and sounding like electricity singing its way through a long stretch of transmission line. It’s lovely, and this game’s easy standout track.

Mega Man 2 would set a new standard for soundtracks in general, with its infectious, irresistible compositions that sound like chiptuned dance tracks from an alternate universe, but Mega Man laid the groundwork for that, and it deserves a great deal of creative credit for the achievement.

Once the six main stages are complete, Mega Man moves on to Dr. Wily’s final gauntlet. This is the pattern that the rest of the classic Mega Man series would follow, and it’s somewhat remarkable how perfect a template was set by the first game. Sure, starting with Mega Man 2 we’d increase the number of main stages to eight, and Mega Man 3 would introduce another set of levels between the main game and the final castle, but those are just tweaks. The core concept of treating the main stages as tutorials — as longform playgrounds for Mega Man to earn and practice with new weapons — with Wily’s Castle testing your ultimate mastery was a sound one, and it’s something the series, wisely, kept around for its entirety.

Mega Man does seem to lose a bit of personality in its final stretch…but, to be frank, nearly all of the Mega Man games do. Wily’s Castle is often memorable for its big setpieces (such as the Yellow Devil in this game, the Mecha Dragon in Mega Man 2, and so on) but the stages themselves are designed to be punishing rather than distinct. As such, I tend not to enjoy these stages as much. There’s more personality in just about any Robot Master stage than there is in any Wily stage, and Mega Man set that precedent for the series, too.

So, yes, it’s aged noticeably. It’s far from perfect. If I could wave my magic wand and fix anything I wanted to fix, I’d be fixing the game all month. And my love for this title is admittedly due to straight, unapologetic nostalgia. There’s nothing — literally nothing — this game does that isn’t done significantly better in nearly all of its nine sequels.

But I love it.

I love it more than I love most games that are, strictly speaking, better.

I love what it is. I love its flaws. I love its silliness. I love its weakest tracks and its most frustrating sections and its crappiest weapons.

I love Mega Man. And, yeah, maybe I love it mainly for the groundwork it laid, but I still come back often to this one.

It’s an absolutely perfect game to complete in one sitting. It’s the perfect length. It’s the perfect balance of fun and challenge. It’s the perfect example of a game that stumbles not because it’s confused, but because it’s doing so many new and exciting things for the very first time. It’s a giddy experience, knowing that every stumble here sets up a grand slam for its sequel.

It’s so much of what I love about gaming in general. And, yes, I still play video games, but few of them hit me the way this raggedy, flawed, ramshackle little daredevil hits me.

When a game comes out today, people ask how long it is. I’ve never understood why.

I can beat Mega Man comfortably in around two hours, and I’m not even that great at it. It’s a short game. There’s no getting around that. There are no unlockables. No alternate endings. No DLC side stories.

But I’ve played Mega Man what has to be a hundred times over the years.

What’s better? A long game you’ll play once? Or a game so good you’ll play it over and over again forever?

The entire Mega Man series answers that question for me. I’ll take a perfect, bite-sized experience any day.

Best Robot Master: Bomb Man

Best Stage: Cut Man

Best Weapon: Thunder Beam

Best Theme: Elec Man

Overall Ranking: 1 (Erm…this will make sense later.)

(All screenshots courtesy of the excellent Mega Man Network.)