“Kitchen Mitts,” The Disco Biscuits

The Wind at Four to Fly, 2006

As I mentioned earlier this week, I am far from caught up on Breaking Bad. I’ve only finally started watching it within the past few months, and there’s no question that it deserves the mountains of praise its gotten. Season five began this week, and while I’m still lagging a few seasons behind, I thought it might be nice to spotlight an episode that really managed to stand out for me. Perhaps this will serve as a kind of time-capsule as well…a record of my thoughts before I knew for sure where things were headed. A moment of reflection before barreling forward, before I know too much of what’s coming for these thoughts to really matter anymore. A time when I get to delight in the fact that I don’t have all the pieces of the puzzle, and so focus that much more intently on what little I do have.

In fact, that’s a more appropriate introduction for this episode than I had intended, because focusing on some small aspect of the larger picture — and doing so deliberately, for whatever reason one may have as an individual — is something of a passive theme here.

Peekaboo comes midway through the second season, and it catches a lot of things about the show in a state of flux. It also stood out to me immediately — and continues to stand out to me — as a clear and permanent favorite. Breaking Bad is at its best when it reveals — nearly always indirectly — an undercurrent of humanity. A living and breathing conscience behind (or below, or within) the meth, the violence, and the devastation. Peekaboo elevates that humanity to a level we haven’t seen before. That, in itself, is not much of an achievement. The achievement comes in how masterfully it’s done.

Peekaboo comes midway through the second season, and it catches a lot of things about the show in a state of flux. It also stood out to me immediately — and continues to stand out to me — as a clear and permanent favorite. Breaking Bad is at its best when it reveals — nearly always indirectly — an undercurrent of humanity. A living and breathing conscience behind (or below, or within) the meth, the violence, and the devastation. Peekaboo elevates that humanity to a level we haven’t seen before. That, in itself, is not much of an achievement. The achievement comes in how masterfully it’s done.

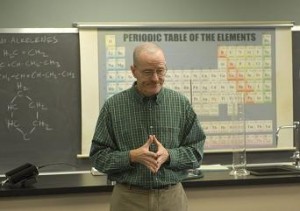

One thing Breaking Bad did quite well from the very beginning was that it allowed for shifting allegiances between its audience and its characters. This was handled brilliantly by centering the show on Walter White, a mild-mannered high school chemistry teacher played with almost meek understatement by Bryan Cranston.

From the very start, we want to like Walter. In fact, we want to like him so much that we make allowances for him. When he actively seeks out the chance to cook meth, we temper our natural feelings for drug dealers with the fact that he just found out he has cancer, and needs to pay for his treatment. When he snaps and berates somebody who doesn’t deserve it, we take into account the fact that he has a lot of stress in his life, with both a son with cerebral palsy a new baby on the way. And when he lies to his wife and keeps those who care most about him frustrated in the dark, we compare him to, say, his boorish brother-in-law Hank, who’s relentlessly obnoxious, racist, sexist and homophobic, and decide that at least Walt’s not that bad.

We don’t need to do these things, but we want to do them. We want to like Walter, so we will work to like him. We want to see the man beneath…and not the accumulation of garbage that continues to compound on top of him.

We don’t need to do these things, but we want to do them. We want to like Walter, so we will work to like him. We want to see the man beneath…and not the accumulation of garbage that continues to compound on top of him.

But Breaking Bad doesn’t let us get away with that for long. Two old friends of Walt’s — Gretchen and Elliot — offer to pay for his treatment, so his justification for cooking meth gets a lot more hazy. His outbursts become more frequent and more severe, which makes it harder to see them as troubled cries for help and easier to see them as a man gradually discovering his inner asshole. And the more we see Walt cheat and steal, the more we see that Hank, on the inside, is a tremendously scarred and scared individual who requires such an obnoxious front simply to make it through the day.

As much as we want to like Walt, and view him as a victim of circumstance, Breaking Bad leaves us with less and less room with every episode to rely on such a reading. In the process, by simple comparison, it also deepens the humanity of the characters around him, and lets us feel more aligned with them than we ever thought possible when they were introduced.

Peekaboo is a perfect distillation of the show’s desire that we question our allegiances to these characters. When we first meet Jesse Pinkman in episode one, he’s a drug dealer, immersed in a dangerous and criminal world that we, as viewers, likely would want no part of. Walter is the outsider, and he comes to Jesse, pleadingly, as an assistant. We can count the number of subsequent episodes on one hand, however, before that dynamic upends itself, and we see that it’s Walter dragging Jesse down, rather than vice versa.

Peekaboo is a perfect distillation of the show’s desire that we question our allegiances to these characters. When we first meet Jesse Pinkman in episode one, he’s a drug dealer, immersed in a dangerous and criminal world that we, as viewers, likely would want no part of. Walter is the outsider, and he comes to Jesse, pleadingly, as an assistant. We can count the number of subsequent episodes on one hand, however, before that dynamic upends itself, and we see that it’s Walter dragging Jesse down, rather than vice versa.

By separating — yet still following — the two characters, Peekaboo lets us see exactly who these people really are. With each making his own decisions, free of judgment or pressure from the other, they are allowed to be themselves.

Jesse’s role in this episode is to break into somebody’s home and threaten them with grievous bodily harm unless they pay him back for the the drugs they stole. Walt’s role in this episode is to have a series of conversations. That Jesse comes out of this looking like an infinitely better human being than Walter could ever be is a sign that this journey will be deliberately confusing, and it’s a testament to Vince Gilligan’s absolutely brilliant storytelling.

Peekaboo picks up from the end of the previous episode, Breakage, in which one of Jesse’s friends, Skinny Pete, is robbed. Jesse accepts this as an understandable risk in the business, and is obviously just happy that Pete is okay. Walter, on the other hand, disagrees. He hands Jesse a gun, and vaguely orders him to “take care of it.”

When Peekaboo opens, Jesse is waiting for Pete on a street corner. He is going to follow Walt’s advice, because a drug dealer that can be pushed around is never more than one push away from being brought down forever. But it’s not his mission that he’s focused on…or, at least, that’s not what he chooses to focus on. He finds a beetle crawling along the curb, and he watches it skitter around. He lowers his hand to it, just to feel it walk across his skin. It’s a little sliver of life among the desolation in the poor part of town, and it holds Jesse magnetized.

When Peekaboo opens, Jesse is waiting for Pete on a street corner. He is going to follow Walt’s advice, because a drug dealer that can be pushed around is never more than one push away from being brought down forever. But it’s not his mission that he’s focused on…or, at least, that’s not what he chooses to focus on. He finds a beetle crawling along the curb, and he watches it skitter around. He lowers his hand to it, just to feel it walk across his skin. It’s a little sliver of life among the desolation in the poor part of town, and it holds Jesse magnetized.

The beetle didn’t need to be there. That is to say, it affected nothing around itself. It neither made the street corner better nor worse. It was no safer, and it was no more dangerous. It did not contribute to the identity of the world around it. It was, therefore, in its own strange way, a kind of escape. By centering his attention on the beetle, Jesse is able to block out everything around him, everything behind him, and everything up ahead.

It’s temporary, as it must be, but it’s something.

Later, after breaking into the home of the couple who robbed Pete, Jesse finds a similar — but far more affecting — sliver of life among the desolation: a little red-haired boy…alone, neglected, and hungry.

Jesse’s reaction to the boy, who is the only one home when Jesse climbs through the window, is one of almost immediate warmth and protectiveness. He begins by asking the boy when his parents will be back, but he quickly loses sight of his main task. The pity in his eyes in unmissable as he watches the boy play distractedly with the duct tape on the arm of the couch…obviously the closest thing he has to a toy in the entire house. The television only gets a station playing infomercials…not, as Jesse would have preferred for the boy, Mr. Rogers. And then, all at once, the boy says that he’s hungry. Jesse still has a mission, but in that very moment it becomes something else.

Jesse’s reaction to the boy, who is the only one home when Jesse climbs through the window, is one of almost immediate warmth and protectiveness. He begins by asking the boy when his parents will be back, but he quickly loses sight of his main task. The pity in his eyes in unmissable as he watches the boy play distractedly with the duct tape on the arm of the couch…obviously the closest thing he has to a toy in the entire house. The television only gets a station playing infomercials…not, as Jesse would have preferred for the boy, Mr. Rogers. And then, all at once, the boy says that he’s hungry. Jesse still has a mission, but in that very moment it becomes something else.

Walt, on the other hand, is going back to work after several weeks’ of medical leave. Apart from a minor detour in his lecture — during which he becomes visibly incensed by how poorly General Electric treated one of their chief engineers — his day is uneventful. When he arrives home, however, he finds Gretchen speaking to his wife. In order to hide the fact that he was paying for his treatment with drug money, Walt told his wife that he had accepted Gretchen and Elliot’s offer, and his wife still believes that. Gretchen, on the other hand, obviously knows that that is not true, and the fact that she doesn’t reveal Walt’s dishonesty demonstrates many things about who Gretchen is as a human being. Walt, whatever else he might be, is important to her. He’s somebody she, however we’d like to define it, loves. She wishes the best for him, and won’t speak up until she has some idea of what that is.

He meets with Gretchen later to explain, only his explanation consists entirely of a reminder that it’s really none of her business. Gretchen is played here with an almost angelic sweetness by Jessica Hecht, who even in the face of disrespect, dishonesty and outright hostility wants only to help her friend. She even reiterates that the offer to pay for his treatment is still on the table…despite the fact that Walt uncomfortably involved her and her husband in the deception of his own family.

He meets with Gretchen later to explain, only his explanation consists entirely of a reminder that it’s really none of her business. Gretchen is played here with an almost angelic sweetness by Jessica Hecht, who even in the face of disrespect, dishonesty and outright hostility wants only to help her friend. She even reiterates that the offer to pay for his treatment is still on the table…despite the fact that Walt uncomfortably involved her and her husband in the deception of his own family.

In return, Walt refuses to tell her anything. He owes her an apology, he admits, but not an explanation. Gretchen pleads with him to accept her help, and Walt, steadying his gaze and speaking with deliberateness and complete control over what he’s doing, chooses to say, “Fuck you.”

Jesse, on the other hand, is feeding the little boy. He makes him a sandwich that seems to only be mayonnaise between two pieces of bread, because there’s nothing else in the house to eat. And when he hears the couple returning home, his first instinct is to put the boy in his room, and tell him not to come out. He doesn’t want to involve him. Pete opened the episode by crushing Jesse’s beetle, and Jesse won’t let this dim light be snuffed out as well.

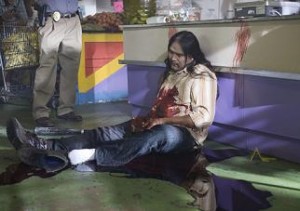

What follows is more in line with his original plan. Jesse intimidates and threatens the couple, gets back the small amount of drugs that is left, and stands around waiting for the man — called Spooge — to break into an ATM that he stole. A victimless crime, Spooge explains, as we see the dead body of the Indian store clerk he stole it from.

Jesse can’t see the irony behind the “victimless crime” that we as viewers can see. That’s our luxury, and we get to view this morbid comparison point through the wonder of editing. Jesse has no such luxury, and that may be why he won’t see that his own victimless crime — dealing drugs — is directly responsible for the squalor around him, and for the hopelessness of that child’s future.

Jesse can’t see the irony behind the “victimless crime” that we as viewers can see. That’s our luxury, and we get to view this morbid comparison point through the wonder of editing. Jesse has no such luxury, and that may be why he won’t see that his own victimless crime — dealing drugs — is directly responsible for the squalor around him, and for the hopelessness of that child’s future.

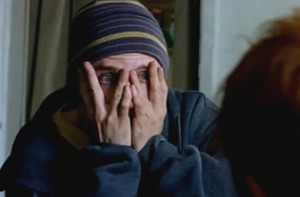

Later in the episode, the boy does come out of his room. He does so because he wants to continue the game of peekaboo that Jesse tried to teach him earlier. Then the child’s confusion was palpable…he had never seen this game before. His parents, it’s safe to say, have never tried to play it — or anything — with him before. And having finally had the experience of an adult who paid him a positive kind of attention, he shuffles out of his room and starts the game again.

As with the beetle, Jesse latches immediately onto this sliver of life among the lifeless. He blocks out his situation and focuses so intently on the magic of the little boy’s innocence, and the urgency of keeping it alive, that he doesn’t notice the boy’s mother coming up behind him to knock him cold. It was an escape, but it was temporary. As it must be.

The two stories end not the way they should end, but the way they must end. Walt returns home, where he learns that Gretchen has called his wife, and told her that they are going to stop paying for Walt’s treatment. Faced, as ever, with an opportunity to stop lying and find some honest way to move forward with his family, Walt chooses instead to extend the deception, and claims that Gretchen and Elliot stopped paying because they are broke. He even offers up a few condescending chuckles at their misfortune.

The two stories end not the way they should end, but the way they must end. Walt returns home, where he learns that Gretchen has called his wife, and told her that they are going to stop paying for Walt’s treatment. Faced, as ever, with an opportunity to stop lying and find some honest way to move forward with his family, Walt chooses instead to extend the deception, and claims that Gretchen and Elliot stopped paying because they are broke. He even offers up a few condescending chuckles at their misfortune.

Jesse, ever Walt’s opposite in this episode, comes to just in time to find the boy’s mother crushing Spooge’s head with the ATM. Her drug-obsessed tunnel vision prevents her from caring much about the fact that Jesse is up and about and brandishing a gun, so he scoops up whatever money he can carry and calls the police, leaving the phone off the hook.

He’s not done here, however.

Jesse returns to the little boy’s room, and engages him in one last round of peekaboo. Only this time, the boy must keep his eyes closed, and not open them until they’re outside. He shuttles the boy frantically past the carnage in the living room, and sits beside him briefly on the front porch.

It’s clear that Jesse wants to offer something to the boy, but there’s nothing he can offer. This merciful — and, of course, temporary — exit from the home is all he can provide. From here, with sirens growing louder in the distance, it’s out of his control. Somebody will always come along to step on the beetle…but Jesse did his part to at least delay that inevitability.

“You have a good rest of your life, kid,” Jesse says, at a loss for anything else and clearly on the verge of an emotion he can’t understand, let alone process. He strolls off with his hands in his pockets, fighting the urge to look back. If he looked back, he wouldn’t have been able to keep going.

And that’s the moment the drug dealer became more sympathetic than the high school teacher.

Walt would not have rescued the child, and Jesse would not have said “Fuck you.”

Allegiances shift. Life is complicated.

So Breaking Bad starts up again tonight. Don’t worry; I have something else planned tomorrow by way of celebration. But for now, with the inescapable commercials, and online advertisements, and interviews and so on, it’s got me thinking about spoilers.

My girlfriend and I are at the end of season two. Tonight, season five begins. We’ve got a lot of catching up to do, and we’re getting there…but we’re enjoying the ride and don’t feel too much of a need to rush. Yet whenever we see some kind of promotional material for the show, we want to look away, stop listening, change the channel…all for fear of spoilers.

And I’m not really sure why. I’ve always maintained — and still maintain — that spoilers shouldn’t matter. If the quality of the piece of art in question is high enough (and for Breaking Bad I’d absolutely say it is) then it shouldn’t matter if you know what’s coming. The pleasure shouldn’t be found in an endless succession of surprises. The pleasure should come from the journey. From the many components that come together to create an engrossing experience.

And I’m not really sure why. I’ve always maintained — and still maintain — that spoilers shouldn’t matter. If the quality of the piece of art in question is high enough (and for Breaking Bad I’d absolutely say it is) then it shouldn’t matter if you know what’s coming. The pleasure shouldn’t be found in an endless succession of surprises. The pleasure should come from the journey. From the many components that come together to create an engrossing experience.

Anyone can shock us. Anyone can jump up and yell boo. That can be a type of pleasure, but it’s not the only type of pleasure. Perhaps if we’re speaking about a summer blockbuster that has no ambition beyond thrilling us with pyrotechnics, spoilers could pull the rug out from under that film’s only trick. But if the acting is good, if the writing is solid, and if the directing is pulling everything together in the right way, then why shouldn’t that be enough?

Recently I was on a forum, and somebody made a comment about something and said, “It’s like the end of Psycho,” by way of humorous comparison. (It wasn’t actually very humorous, but there you go.) A second poster replied, “I haven’t seen Psycho, what happens?” And then the first told him to sign off immediately and go watch it.

Nothing wrong with that, but he justified this by saying something to the effect of, “Go watch it before you get spoiled. You’re very lucky if you don’t know the ending, so go watch it so you can experience it the right way.”

That’s troublesome to me on several levels. First, and less importantly, the ending was already spoiled in the thread by making that comparison in the first place. Shouting out “Go watch it now before you have the twist spoiled for you!” will keep him on guard for that twist, and that’s just as bad as — if not worse than — knowing what’s coming.

But secondly, it suggests that Psycho isn’t worth watching — or isn’t as worth watching — if you know what’s coming.

And, I’m sorry, but that’s bunk.

I knew the ending of Psycho well before I ever saw it. It may have even been the first thing I knew about it. Yet when I finally sat down to watch the film, I was absolutely ensnared by Hitchcock’s chilling masterpiece. It had nothing to do with not knowing what was coming next…it had to do with the film being a genuine masterwork by a man who knew what he was doing.

I knew the ending of Psycho well before I ever saw it. It may have even been the first thing I knew about it. Yet when I finally sat down to watch the film, I was absolutely ensnared by Hitchcock’s chilling masterpiece. It had nothing to do with not knowing what was coming next…it had to do with the film being a genuine masterwork by a man who knew what he was doing.

By now, most people know the dark secret of Norman Bates. I truly doubt, however, that it interferes with their ability to enjoy that film. If it does, then I can only concede that they must be watching films the wrong way. There’s really no other way to argue it.

When Kate and I were standing in line to see Moonrise Kingdom recently, a man walked by and shouted to everybody, “At the end of the new Wes Anderson movie, they all die.” That didn’t turn out to be true (Oops! Was that a spoiler too?), but if it had been true, so what? Does that make the journey Anderson has planned for us less magical? We may know where we end up. Does that matter? Should that matter? The film isn’t about its own final scene or scenes. If it were, it’d be around three minutes long. No, instead Anderson had more to say. We weren’t there to be shocked by an ending…we were there to be led by the wrist by a man we wished to spend time with. Is that an experience that can even be spoiled by advance knowledge?

What’s more, I knew that Rosebud was a sled. I knew that everybody rallied around George Bailey. And I know that Darth Vader is Luke Skywalker’s father. So do a lot of people. And yet I doubt that it’s interfering with their enjoyment of those films.

And why should it? Certainly the revelation of Vader’s paternity earned a few gasps in theaters, but was it what resonated most with the people in the audience? Probably not…or, at least, the shock was not what resonated most. If it had been, there wouldn’t be much of a reason to rewatch it now that that coin has been spent. And yet — and please correct me if I’m wrong — I’m under the impression that people do still rewatch the Star Wars films.

So there must be something else. People know there must be something else. After all, how many people can say that their favorite book, film, song, or anything else is something that they’ve only experienced once? No, more likely it’s something they’ve returned to — and continue to return to — many times over, despite the fact that they “know what happens.” They’re already self-spoiled. And it doesn’t detract from their enjoyment. If anything it may enhance it, as knowing what’s to come can give them a stronger appreciation for the steps the artist must take in order to arrive there.

So there must be something else. People know there must be something else. After all, how many people can say that their favorite book, film, song, or anything else is something that they’ve only experienced once? No, more likely it’s something they’ve returned to — and continue to return to — many times over, despite the fact that they “know what happens.” They’re already self-spoiled. And it doesn’t detract from their enjoyment. If anything it may enhance it, as knowing what’s to come can give them a stronger appreciation for the steps the artist must take in order to arrive there.

That’s fair. That’s good. I agree with me.

And yet…I still don’t want to know what happens on Breaking Bad.

I know spoilers are a ghost we shouldn’t be afraid of…but when I see it coming, I run in the other direction.

Even though I know better.

Why? What’s so scary about knowing what’s to come? Isn’t it one of mankind’s most clearly recurring wishes to know, in some way, what the future brings? We can prepare ourselves for it. We can steel ourselves against it. We can look forward to it.

So why, given the opportunity to know the future in micro, are we so compelled to shut it out?

I don’t have an answer. I don’t know why. You can rationalize it all you like, but, in the end, we don’t want to know what comes next. At least, not until we get there.

That’s fascinating to me. Because I really, genuinely, honestly, don’t know why.

Here’s to 50 years, boys…