See you after the movie.

Oliver Onions, “Zorro is Back”

Zorro Original Soundtrack, 1975

See you after the movie.

And so Wes Anderson month draws to a close, as Moonrise Kingdom lingers hesitantly upon the horizon for another couple of days, and we conclude our month-long reflection on that which has come before.

This, however, is not meant to be a particularly thought provoking piece. It’s not what you will remember — if you remember anything at all — and it’s not going to make any grand and conclusive statement. It’s just a final thought before we move forward, before Wes Anderson officially has another release under his belt, and before Moonrise Kingdom takes its rightful place beside his other films, so that we can wait expectantly again for rumors of the next.

It’s a piece, or, perhaps, a tribute, dedicated to the strong relationship between one man and his voice. Because that, without question, is Anderson’s greatest strength, and it’s what his biggest fans see when they react so strongly to his work. It’s also what his most vehement detractors see, though they might not realize that.

Anderson’s regularity in terms of his core cast, reappropriated pop songs, emotional dissonance, familial dissatisfaction, costumes, meticulous set design, original score composers and even typefaces all lead certain members of his potential audience — and certain reviewers — to deride him as somebody who is either incapable of evolution or totally opposed to it. Personally, I see all of that as evidence that Anderson found his voice quickly and firmly, and therefore sees no benefit to hollow deviation.

I wouldn’t see a benefit either. Evolution, in an artistic sense, should never occur for its own sake. An artist must always be evolving toward something, not in a state of constant flux. For an artist, comfort is paramount. That’s when artists are free to realize their visions. The less an artist has to worry about the relatively minor aspects of their production, the more they can focus on crafting a compelling core experience.

Anderson has spent his (admittedly young) career surrounding himself — like Steve Zissou — with a core group that he knows he can trust to realize smaller aspects of his vision. With those team members in place, he can focus on what the production is. It frees him to make decisions he might not otherwise have the time to get to.

The films of Wes Anderson don’t represent a refusal to evolve…they represent a confidence of vision. Anderson knows his own hallmarks; he’s not deaf to what critics say and he’s certainly aware of the amount of money each of his films takes in. (Or, of course, fails to take in.)

But he’s an artist, not a businessman. He knows that a commitment to his strengths are what will benefit him — and his audiences, even if it takes them a while to understand that — in the long run. His place in film history won’t be reserved for a man who shapes himself differently with every film in a doomed attempt to satisfy a fickle audience. No, his legacy will be a sturdy one, rooted in a single spot…because it just so happened that he found his calling almost immediately.

Many artists search their entire lives for a voice. Those artists have a need to evolve. Along the way they attempt different things, shed what doesn’t work, and glide — hopefully — toward a strong foundation of what does. From that framework, their experiments benefit from confidence, from understanding, and from the sheer satisfaction of having found it.

Wes Anderson was fortunate enough that he didn’t have to look very far. To put it another — equally accurate — way, we are fortunate that he didn’t have to look very far.

He has a lifetime of creativity ahead of him, and the luxury of already knowing how to say whatever it is he’ll need to say next.

I don’t need Anderson to pen a straight romantic comedy, or a detective story, or a historical drama just to prove that he can. Because that wouldn’t be him. That wouldn’t be his heart, those wouldn’t be his words, and that wouldn’t reflect his vision.

I don’t want Anderson to change. I want Anderson to continue to grow. In other words, I want Anderson.

Oftentimes, growth lies inward.

Anderson’s characters know that. Anderson knows it too.

And somehow, I already know that Moonrise Kingdom is going to be derided by many as being “more of the same.”

That’s okay. From a distance, it all looks like the same color.

To those willing to come a little closer, however, Anderson’s painting with a wealth of different shades.

This is an adventure.

The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou is a strange film. It’s about family, it’s about celebrity, it’s about revenge, and it’s — arguably primarily — about the relentless intrusion of reality into a life carefully cultivated. It’s many things throughout the course of its runtime, and it’s never less than two distinct things at once. It is, I would argue, one of Anderson’s densest films, and it’s also my personal favorite, making it a perfect candidate for my first installment of Anatomy of a Scene.

Originally I wanted to do the Maddox Hill Cemetery scene from The Royal Tenenbaums — and there’s no reason I can’t do that later — but for the time being I think it got a fair enough bit of attention in my 10 Most Affecting Wes Anderson Moments feature. Instead I’m turning to the Loquasto International Film Festival scene from The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou. It’s a very early sequence in the film that really shows Anderson — and Mothersbaugh, and Murray — at their indirect best. Every line and detail hearkens forward to what’s to come, making it a brilliantly constructed overture of sorts, and yet, viewed out of context, it functions perfectly well as a piece of work unto itself, standing alone as a series of emotional triggers for one man who is having a terrible night…and being required to suffer in public.

Celebrity oceanographer / documentarian Steve Zissou has just premiered his latest and most tragic film to an audience that responds with a distinct lack of interest. Steve emerges from a post-screening Q&A session that has gone no better, and that’s where the scene begins. We open on a vast and relatively empty hall, where Antonia Cook (played by the late Isabella Blow) is standing stock-still and dead center, waiting for Steve to come through the door so that she can compliment him on his film — which we can pretty safely assume she wasn’t in the room to see. She’s more interested in awaiting her chance to flank a celebrity than she is in actually watching the films that made him famous in the first place. It’s a sort of only-half-aware posturing, an appreciation of celebrity without consideration for actual merit, that Steve himself suffers from as well.

In the background we can also see the old man who will later ask Steve for his autograph; he can actually be glimpsed several times throughout this sequence before he gets his moment, suggesting that Steve has overlooked him, and, indeed, overlooks as many people as he can afford to, preferring isolation even during this grand event. When the old man eventually does get his chance, he needs to be introduced by Vladimir Wolodarsky, Team Zissou’s physicist / original score composer. As we’ll see later in the film, it really is up to Team Zissou to keep their captain grounded, and rooted to the world beneath him…if not exactly to reality.

The name “Loquasto International Film Festival” is also loaded, making oblique reference to Santo Loquasto, a famous production designer who worked on more than 60 Broadway shows, as well as many Woody Allen films — netting him several Academy Awards for his work with that great director. In short, it’s a film festival named for a production designer rather than a director, a writer, or an actor. It passively highlights the importance of design, of construction, of careful assembly…over, say, quality. That’s Steve Zissou’s world in a nutshell.

After Antonia, Steve meets with Oseary Drakoulias, head of the financially-questionable production company that publishes his films. Oseary is speaking with Larry Amin, ostensibly casually, but as Steve correctly intuits, Oseary is both flirting with Amin and angling for money. In more controlled circumstances, Steve might shake hands and move along, but after having to field questions about his closest friend’s death he’s not interested in glad-handing. Oseary immediately berates Steve for his insensitive — though accurate — response to the situation, and this berating doesn’t seem to affect Steve at all. He’s feeling as low as he’s ever been, with Esteban’s death just the latest addition to a massive stack of tragedies he’s never gotten around to dealing with.

We should take a moment to talk about the score before we get too far ahead, and feel free to listen to it in isolation from the scene. It’s a genuine Mothersbaugh masterpiece, holding true to its main theme but allowing itself to drift away periodically, before a crash of strings to pulls it back down to Earth. This piece of music is similar in that regard to Mothersbaugh’s “Sonata for Cello & Piano in F Minor” from The Royal Tenenbaums, and this scene serves a similar purpose to that one in Anderson’s previous film as well. Both scenes show us where the characters are now, in present day, plying us with the basic information we’ll need in order to interpret everything that comes next.

I’d argue that both this scene and this piece of music represent a step forward in artistic merit, however, as the earlier scene relied on narrator Alec Baldwin to keep us focused and attentive to the right details, whereas this scene dumps us disoriented into the great hall, just as Steve is dumped, and requires us to make our way, without assistance, through the onslaught of characters, dynamics, and emotions on display. The score, likewise, has a more organic momentum to its digressions than “Sonata,” what with its abrupt drum solos and reggae breaks.

Steve’s next stop is a photo op with his “nemesis,” Alistair Hennessey (played with gleeful condescension by Jeff Goldblum). Hennessey is, as the film will both now and later prove, exactly what Steve is not: collected, well organized, efficient, and flush with cash. He also used to be married to Eleanor Zissou, Steve’s wife. We see the differences immediately upon Hennessey’s arrival in this scene: he’s smiling, he’s shaking hands, and he’s thronged by reporters. He’s in his element — unlike Steve, who is quite clearly a fish out of water…so to speak… — and this is what he lives for. He’s also — it’s important to note — clutching an award.

He makes friendly overtures toward Steve — even though they’re at least passively adversarial. He repeatedly opens the door to conversation and attempts to engage Steve while the cameras flash all around them, but Steve won’t so much as look at him or smile for the photographers. In fact, Steve doesn’t smile once throughout this entire long scene, slipping instead to varying depths of desperation and dissatisfaction. And that’s the difference between Steve and Hennessey: Hennessey is satisfied with who — and where — he is. He can afford to humorously prod Steve about his film, both because he’s happy with who he is, and because he knows Steve is not. These are two old hands in the same industry, but Steve won’t even give Hennessey a straight answer when he asks the simple — and valid — question of whether or not the jaguar shark even exists.

It’s also worth drawing attention to the Christmas decorations, which sporadically populate the hall. While The Life Aquatic contains no explicit references to Christmas, it does, in several ways, have Christmas in its blood. For starters, it was released in theaters on Christmas Day in 2004. It stars Bill Murray, who can number among his most famous films Scrooged, which is a humorous adaptation of A Christmas Carol. The Life Aquatic also deliberately echoes one of the most famous images in A Christmas Carol by ending the film with Steve hoisting Klaus’s nephew onto his shoulders like Tiny Tim. In fact, the entire sequence at the Loquasto International Film Festival functions in a thematically similar way to the first phase of Scrooge’s rehabilitation: uncomfortable — and unwilling — exposure to the ghosts of the past. In fact, I’ve long wanted to write an essay about The Life Aquatic functioning as an oblique adaptation of A Christmas Carol, but that’s a project for another time…

Next we meet Steve’s wife, Eleanor Zissou. As we’ll learn shortly, she is “the brains behind Team Zissou.” This is important to note, because it explains why he remains in a relationship with her. The two have a mutual dislike for each other that is only infrequently overcome by whatever tenderness survives between them, but she has the money that Steve needs to keep shooting, as well as knowing “the Latin names of all the fish and everything.”

It’s less clear why Eleanor stays with him, though. Steve is quick to point out that Hennessey isn’t much of a threat to their marriage as, in spite of his history with Eleanor, his homosexual tendencies keep him otherwise engaged. Beyond that, though, there’s less incentive for Eleanor to stay married to Steve than for Steve to stay married to Eleanor.

Once Eleanor steps away, Steve is approached by a woman — in attire suitable for a mermaid — who wishes to say hello. Steve leans in to kiss her, but she does not want to be touched by him. (It’s pretty easy to insert the word “anymore” here.) When Eleanor returns he attempts to introduce them, but Eleanor cuts him off by asking if he really wants to put her through this, resulting in both women leaving him in separate directions. Steve, alone, pops a pill.

It’s a loaded moment in many ways, and while we never see the woman again, Steve’s womanizing is absolutely to the fore several times in the future. Here it threatens his relationship with his wife, and before long it will threaten his relationship with his son.

As with everybody tonight, Steve is being exceptionally candid, confessing to Eleanor that he’s “right on the edge,” and that he doesn’t know what comes next. When both women abandon him and he swallows a pill, it’s clear that he does, in fact, know what comes next…he just really wishes he didn’t.

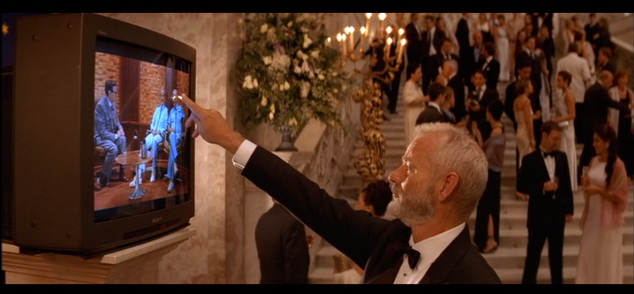

When I said earlier that Steve doesn’t smile in this scene, I was incorrect. I should have said that present-day Steve doesn’t smile in this scene, as we do see some archival footage of an early interview on the film festival’s monitors, presenting a blonde and happier Steve from better times.

The interviewer, Antonio Monda (an interestingly similar name to Antonia Cook’s), asks what Steve is to Team Zissou. Steve chuckles, but is clearly enough at a loss for a reply. Esteban places a hand on him and says, “He’s the Zissou.”

It’s exactly the kind of response that could be interpreted either way, but from Esteban, Steve hears it as a compliment. What is Steve? Esteban’s reply could suggest either that he’s everything to the team — in fact, is the team — or that he’s nothing but a name. Steve interprets it — correctly, I feel — as meaning the former. From Hennessey, it would have been the latter.

But there is no more Esteban. He’s been taken from this world and from Team Zissou by the jaguar shark and Steve’s negligence, and Steve it’s Hennessey who’s here instead. So what, now, is Steve? It’s a question our central character is going to have a lot of trouble answering over the course of them film, and it’s one to which he will go to great lengths in order avoid answering at all.

He reaches out to Esteban and a tiny spark flashes at his fingertip. Bright, urgent…and then gone. A metaphor for both Esteban himself, and also Steve’s celebrity.

Next we meet Klaus (Willem Dafoe), who introduces Steve to his nephew. His nephew has a gift for Steve…a crayon ponyfish. It’s unlikely to be anything Steve hasn’t seen before, and it’s less likely to be anything particularly impressive — the plastic bag suggesting that Werner saved his allowance and purchased it from a pet store — but it’s a tangible reminder of Steve’s youthful ambitions. It’s an image out of his own past, an infatuation with the sea and with those who explore it. Every creature is magical, if you view it through the right lens, which in this case is the innocence of youth.

This is why Anderson created all of his sea creatures from scratch, using stop motion rather than actual, living beings. Everything is invented, and therefore everything is new to us. They need to be, so that they can stand out as magical, and not mundane. Steve’s tired and careless approach to the wondrous worlds that unfold regularly around him is a symptom of a professional and personal malaise…not any shortness of majesty in those worlds themselves. Fresh eyes like Werner’s — and implicitly ours — can still see that. Steve’s eyes are tired, but we see a flash, ever so fleeting, of admiration for the boy who admires him in return…a memory of a simpler time, when Steve really cared about what he was doing.

This is also the first time we see Steve interact with other members of Team Zissou, who, as we saw earlier in the film, don’t particularly have much experience with the sea. Their titles are telling…Steve lists camera men, sound men and script girls, but his crew is tellingly free of oceanographers and marine biologists. Instead, Steve surrounds himself with a crew that can insulate him, artificially, from the world around him. Rather than exploring and discovering the unknown, Steve prefers a life determined by scripts, lighting levels, and carefully managed interactions. He’s comfortable only when he doesn’t have to deal with the unforeseen, but it didn’t used to be this way.

This lack of comfort is on display when he’s finally confronted by the old man in pajamas, who has come to the film festival with a stack of posters advertising Steve’s previous movies. He seeks out an autograph and at first Steve is willing to comply.

Eventually, however, Steve tells him to leave. There are too many posters to sign, and this affects Steve in precisely the opposite way that his encounter with Werner affected him moments before. (“I could go either way” is a very telling line…and, in fact, he ends up going both ways. First one, and then the other.) Here, Steve is confronted with evidence of his past. Not an idealistic reminder as he saw in Werner, but a physical, unchangeable record of what he’s actually done. The films advertised on these posters don’t strike one as being particularly good, as some of them have only the most tenuous connections to the sea at all. The old man may be a genuine fan, or he might just be a collector. Either way, he’s handed Steve a record of his professional — and progressing — degradation, and then asked him to account for every one.

It’s a disappointment that frustrates Steve and brings him immediately back down from the relative high of Werner’s gift. Meanwhile, we can imagine Klaus being particularly happy that things went so well with Steve and his nephew. As morbid as it might seem, Klaus is clearly expecting a battlefield promotion. Esteban is dead, and that’s tragic…but it also leaves a vacancy for Steve’s right hand man. Klaus has been a long-suffering and fragile member of Team Zissou, who thought of both Steve and Esteban as fathers to him. This next voyage will be his chance to step up and impress his father figure…unfortunately, this next voyage will also feature the return of Steve’s prodigal — if not necessarily actual — son Ned, which relegates Klaus again to the sidelines, and sinks him immediately into the depths of aggressive misery.

For now, however, Klaus can look forward to the future…as Steve seeks desperately to isolate himself from the past.

As Steve’s long, dark, wine and cheese party of the soul winds down, he finds a welcome quiet moment as he gazes longingly in Eleanor’s direction. Of course, he’s also gazing off at the Belafonte, his ship, where his life has structure, if not necessarily meaning. It’s a place where he can be safe (where, indeed, he employs a Safety Expert)…it’s the ability to set sail, and leave everything — absolutely everything — in the world behind.

For Anderson, it’s no coincidence that Eleanor is in that shot as well. After all, she’s what keeps Team Zissou afloat. He needs her, whether or not he likes her. In a remarkable bit of restrained cinematography, we linger for a short while on this view, and then return to a very long shot of Steve, silent and unmoving. He ends up being either too intimidated or too disinterested — or both — to approach his wife and speak to her, so he settles instead for raising his hand in a brief, motionless wave.

It’s impossible not to see this as well as the universal gesture for “stop.”

There’s a beautiful swell in Mothersbaugh’s score, and Steve comes back to Earth.

Steve’s night isn’t over yet, however, as there’s one last obstacle between him and the yearned-for safety of his boat: the crowd. Steve has no interest in any of them, any moreso than he had in the old man earlier, but one person gets his attention by suggesting loudly that Steve should be in mourning for Esteban…and then asking who he intends to kill in part two.

This is Steve’s collapse, as the weight of the evening and every conflicting emotion he’s had all night surge to his head, and he attacks the man physically.

It’s interesting that Steve doesn’t snap until after the man takes his picture (an aural “snap” itself), thus recording, yet again, another failure of Steve’s. As a celebrity, Steve must cope with his mistakes in public. He’s recognizable and famous, and as such doesn’t have the luxury of coming to terms with his shortcomings and failures in solitude.

It’s interesting that in Rushmore, Bill Murray’s character also seeks refuge beneath the waterline. It’s a chance to separate, a chance to be of the world and yet also free from it. Here he must face his failings head-on, and he responds to them by lashing out.

We also see Team Zissou come to his aid not by stopping Steve or pulling him out of the fray, but by hopping the barricade and assaulting the heckler themselves. They serve as a wall — in this case literally — between Steve and the consequences of his actions. Their job is to keep their captain safe — physically, mentally, emotionally, howsoever necessary at any given time — which is why he has come to rely on them more than he’d ever be able to rely on a group of competent oceanographers.

In the scuffle, the bag containing Steve’s crayon ponyfish is ruptured. While Steve would have no trouble replacing it and indeed sees more remarkable things daily, he takes a champagne glass from another partygoer and rescues the ponyfish with it, hoisting it above his head like a banner as he walks away.

But it’s not just the ponyfish he rescued — as Steve’s made clearly known, he’s not sentimental enough about sea-life to keep from killing it for personal reasons — it’s Werner’s idealism. It’s youth. It’s a message from the past, one of many he received tonight but the only one he can bear to hold onto. It’s a reminder maybe not of what Steve Zissou is but at least of why Steve Zissou is.

It’s also a small creature. Like Werner. And like Steve was once, too. It’s a creature unable to survive in the environment around him, which requires itself to be kept safe and secure until it can return to its home in the sea. Steve understands.

When it came time for me to decide which film to spotlight for Wes Anderson month, I found it to be a pretty difficult decision. I could easily have turned to personal favorites The Royal Tenenbaums and The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou and rattled for a few thousand words about why I think they’re great. Or I could have done a piece about why The Darjeeling Limited feels like Anderson catching himself off guard, with mixed — though ultimately excellent — results. And, of course, I could have written a piece about either Bottle Rocket or Fantastic Mr. Fox, giving myself an opportunity to explore critically my misgivings.

But all of that would have been almost too easy, especially when, all month long, Rushmore has been calling out to me, and attempting to instill itself in my mind as the perfect ambassador of Anderson’s form and methods. Eventually, I caved to its charm and confidence, and accepted what it told me wholesale. Rushmore positioned itself so effectively in my mind the same way Max Fischer positions himself so effectively in the film: by already believing itself to be right. That’s also how Anderson, at his best, manages not only to overcome contrived situations and wooden performances, but to harness their dormant energy and ultimately use them to his creative advantage. It’s a whole lot of charm, a larger amount of confidence, and a willingness to invest absolutely everything. Rushmore embodies all of that perfectly.

But all of that would have been almost too easy, especially when, all month long, Rushmore has been calling out to me, and attempting to instill itself in my mind as the perfect ambassador of Anderson’s form and methods. Eventually, I caved to its charm and confidence, and accepted what it told me wholesale. Rushmore positioned itself so effectively in my mind the same way Max Fischer positions himself so effectively in the film: by already believing itself to be right. That’s also how Anderson, at his best, manages not only to overcome contrived situations and wooden performances, but to harness their dormant energy and ultimately use them to his creative advantage. It’s a whole lot of charm, a larger amount of confidence, and a willingness to invest absolutely everything. Rushmore embodies all of that perfectly.

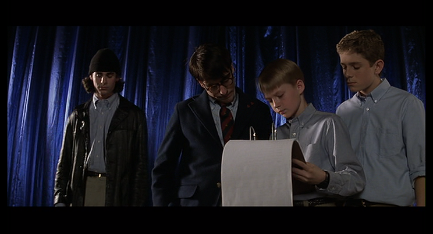

After all, Rushmore itself is a movie about manipulation, and I mean that in both the constructive and reductive senses of the word. Max Fischer is seemingly a 15-year-old omni-prodigy, though he doesn’t happen to be particularly good at anything. Or, perhaps, he’s not particularly good at anything other than manipulating people into thinking he’s good at things. It’s enormously telling — and appropriate — that the only thing that earns Max any genuine accolades throughout the course of the film is his work as a playwright.

Writing and directing plays allows him to work with his most effective resources: the tools of manipulation. Every line spoken, every step taken, every lighting decision and element of background animation are within his control, and that’s how he likes it. By default, Max is not easily shaken. Upon given notice that he’s being placed on sudden-death academic probation and may be kicked out The Rushmore Academy, he responds coolly and attempts to strike a reasonable bargain to remain enrolled. By contrast, when one of his actors fails to deliver a minor line in his stage adaptation of Serpico, Max becomes emotional, aggressive, and instigates physical violence.

Plays are where Max feels the most control, and they’re where he can rely on retaining that control. As evidence, it’s no coincidence that his assemblage of actors go under the name The Max Fischer Players. These are Max’s projects, in his hands and under his control, and if anything threatens his complete dominion over them he feels threatened, and he will lash out.

Plays are where Max feels the most control, and they’re where he can rely on retaining that control. As evidence, it’s no coincidence that his assemblage of actors go under the name The Max Fischer Players. These are Max’s projects, in his hands and under his control, and if anything threatens his complete dominion over them he feels threatened, and he will lash out.

It’s also no coincidence that hands are a recurring motif in Rushmore. In fact, the film is largely — arguably entirely — about Max’s relentless manipulation of the world around him. Interestingly, the word “manipulate” itself derives from the Latin manus, which means hand. Manipulating means literally to position by hand. The word “manufacture” shares a similar original, meaning to create by hand, and both “manipulate” and “manufacture” feel like inextricable parts of Max’s daily routine. (The Latin connection is also a pleasant surprise when considering this within the context of the film.)

All of this goes to justify and explain the film’s compulsive interest in hands, and what one can do with them. Perhaps most overtly, Max lies about receiving a handjob from Mrs. Calloway, the mother of his chapel partner Dirk, which is an interestingly specific fabrication. Handjobs also factor into Dirk’s deliberately needling letter to Max later in the film, when Dirk claims he witnessed Miss Cross and Mr. Blume giving them to each other. The comedy comes from the fact that Dirk clearly doesn’t know what a handjob is — they’re rather necessarily one-sided in heterosexual relationships — but when Max believes it, he reveals that he doesn’t know either. It’s something that sounded appealing to Max, and its emphasis on handiwork — so to speak — fits in perfectly with his personal ethos, and lent itself to a thematically fitting lie.

All of this goes to justify and explain the film’s compulsive interest in hands, and what one can do with them. Perhaps most overtly, Max lies about receiving a handjob from Mrs. Calloway, the mother of his chapel partner Dirk, which is an interestingly specific fabrication. Handjobs also factor into Dirk’s deliberately needling letter to Max later in the film, when Dirk claims he witnessed Miss Cross and Mr. Blume giving them to each other. The comedy comes from the fact that Dirk clearly doesn’t know what a handjob is — they’re rather necessarily one-sided in heterosexual relationships — but when Max believes it, he reveals that he doesn’t know either. It’s something that sounded appealing to Max, and its emphasis on handiwork — so to speak — fits in perfectly with his personal ethos, and lent itself to a thematically fitting lie.

Miss Cross also invokes the concept of a handjob when she asks Max what he’d tell his friends if they did sleep together. She also asks whether or not he’d claim that he fingered her…another clearly (and more accurately phrased) reference to his hands in a sexual sense.

Less obscenely, Max uses his hands to make statements that he cannot — or chooses to not — make through his words. He orders a construction crew to shut down by gesturing to them, he signals to a disc jockey to play a song he’s selected specially for the occasion, and he flashes Dr. Guggenheim the middle finger after starting a fire outside of his office window. For an artist, particularly one who engages regularly in strongly physical extra-curricular activities, the hand can be as expressive or more expressive than the voice. Even his handwriting is deliberately considered and executed, with a careful calligraphy employed even his least formal note taking.

Less obscenely, Max uses his hands to make statements that he cannot — or chooses to not — make through his words. He orders a construction crew to shut down by gesturing to them, he signals to a disc jockey to play a song he’s selected specially for the occasion, and he flashes Dr. Guggenheim the middle finger after starting a fire outside of his office window. For an artist, particularly one who engages regularly in strongly physical extra-curricular activities, the hand can be as expressive or more expressive than the voice. Even his handwriting is deliberately considered and executed, with a careful calligraphy employed even his least formal note taking.

Max’s hands serve as a clear symbol of who he is, and of what he does. That’s why when Dirk refuses to take his hand after a school-yard scuffle, it’s much more clearly a rejection of who Max is as a person than a simple — though loaded — refusal to help him up. Dirk eventually apologizes for not taking his hand, and Max, in the same conversation, apologizes for claiming that his mother gave him a handjob. A hand caused both insults, and an apology — pardon the phrasing — waves them away. Soon afterward Max overcomes his funk by taking the kite from Dirk and flying it himself…a physical engagement and act of control that immediately causes him to begin brainstorming a new endeavor: The Kite Flying Society, with a flood of names for potential members following close behind. It’s Max regaining control…however far removed from what he might have lost on his way down.

This unstoppable yearning for absolute control is endemic to Anderson as well, and the meticulous structuring of each of his films — starting, of course, with Rushmore — makes that clear. Like Max, there’s not a set detail that escapes his notice, or that could possibly receive too much of his consideration and attention. Like Max, he demands limitless artistic control over his actors, their wardrobes, and the soundtracks playing behind them. And, like Max, his critics would argue that in this search for clinical perfection, he misses the human element that makes these pieces of art worth creating.

This unstoppable yearning for absolute control is endemic to Anderson as well, and the meticulous structuring of each of his films — starting, of course, with Rushmore — makes that clear. Like Max, there’s not a set detail that escapes his notice, or that could possibly receive too much of his consideration and attention. Like Max, he demands limitless artistic control over his actors, their wardrobes, and the soundtracks playing behind them. And, like Max, his critics would argue that in this search for clinical perfection, he misses the human element that makes these pieces of art worth creating.

The latter is a viewpoint I don’t particularly endorse, but it does mean that Anderson’s taking a sideways approach to humanity, which to some is one of his clearest hallmarks and to others is one of his most distracting tendencies. For Max, it was more a question of realizing that those around him — along with the world as it actually is, as opposed to how he wishes it to be — are beautiful in their own way, and worthy of his respect and appreciation for who they are. Max wants to see the world as a series of purposefully constructed moments marching toward a grand statement or triumph…which, it must be said, is exactly the environment Wes Anderson creates for him within the film. But, along the way, those moments reveal weakness, and a genuinely pained emotional core.

It’s not until the end of the film that Max can accept that, sometimes, we just need to take the world for what it is, and realize that while we can’t have everything we think we want, we can live a perfectly fulfilled life with what we have. His father may only be a barber, but that’s a disappointment only in the relative sense that he’s not a neurosurgeon…a fiction Max invented for the sole purpose of being taken more seriously, but which instead proves to be a painfully distinct schism between his fantasy and the real world around him.

It’s not until the end of the film that Max can accept that, sometimes, we just need to take the world for what it is, and realize that while we can’t have everything we think we want, we can live a perfectly fulfilled life with what we have. His father may only be a barber, but that’s a disappointment only in the relative sense that he’s not a neurosurgeon…a fiction Max invented for the sole purpose of being taken more seriously, but which instead proves to be a painfully distinct schism between his fantasy and the real world around him.

And Margaret Yang, a classmate whom he remakes into something more attractive by removing her glasses, doing her hair and dolling her up with makeup, fails to capture his fancy even after all of his meddling. When he dances with her at the end of the film and is sweetly embarrassed by the possibility that she might now be his girlfriend, it’s the real Margret that he finally embraced…not the deliberately manufactured fiction that he put on display in front of everybody. (It’s also worth noting that the character of Margaret Yang was originally intended to have a missing finger — a concept that was latter reappropriated for use in The Royal Tenenbaums but would have even further advanced this film’s manual infatuation.)

Max Fischer’s world is less a place to live than it is a stage upon which he intends to will to life a carefully shaped destiny. He cultivates the world like a gardener, pruning what doesn’t work, attending to what does, and if there’s anything missing that he really wants, he’ll go out there and plant it himself. It’s precisely the opposite of Herman Blume’s worldview, which is more akin to being trapped in a Hell of careless accumulation. He ends up married to a woman he doesn’t love, with two brutish sons he never expected to have, and he’s envious of a 15-year old boy…not because he has everything together — he’s already heard from Dr. Guggenheim what a lousy student Max is — but because he seems to have everything together.

Max’s confidence is seductive. It doesn’t matter to Mr. Blume what Max’s situation actually is — from bad grades to being a simple barber’s son — it matters to him that Max has found a way to thrive within those circumstances, something Blume’s not been able to do. Of course, Max’s very act of thriving is confined to a rather thin and obvious bubble, but it’s more than Blume has, and it’s understandable that he would be seduced by that, just as fans of Wes Anderson’s are seduced by his own, just as clearly manufactured, bubble. It’s a worldview that certain people — Blume and ourselves — active want to buy into.

Max’s confidence is seductive. It doesn’t matter to Mr. Blume what Max’s situation actually is — from bad grades to being a simple barber’s son — it matters to him that Max has found a way to thrive within those circumstances, something Blume’s not been able to do. Of course, Max’s very act of thriving is confined to a rather thin and obvious bubble, but it’s more than Blume has, and it’s understandable that he would be seduced by that, just as fans of Wes Anderson’s are seduced by his own, just as clearly manufactured, bubble. It’s a worldview that certain people — Blume and ourselves — active want to buy into.

As much as Max attempts to restructure the world around him through sheer force of will, Blume — far too late — now attempts the same thing with Max. After all, Ronnie and Donnie are the two sons he never thought he’d have. The unspoken sentiment here is that Max is the son he thought he’d have: an achiever, a charmer, and — seemingly — a self-assured young gentleman. That Max would probably also have preferred being born to this steel mogul is also unspoken, but equally clear, and the fact that they both settle upon Miss Cross in a romantic way that skews enormously toward the motherly on both sides is also quite telling. These are people attempting to build their worlds…Blume for the first time, and Max continually so.

They may be at different stages in their lives, but they yearn for the same things. Blume and Max may seem perfectly suited as father and son surrogates, but as Miss Cross — and many other aspects of the film, including the escalating prank war that nearly results in death — reminds us, they’re made for each other. They’re friends, whether they like it or not, and whether they know it or not. The love story would involve Miss Cross if Max had anything to say about it — his frustration here stems from the fact that, no, for once he doesn’t have anything to say about it — but, in reality, it’s Blume that’s his soul mate.

They may be at different stages in their lives, but they yearn for the same things. Blume and Max may seem perfectly suited as father and son surrogates, but as Miss Cross — and many other aspects of the film, including the escalating prank war that nearly results in death — reminds us, they’re made for each other. They’re friends, whether they like it or not, and whether they know it or not. The love story would involve Miss Cross if Max had anything to say about it — his frustration here stems from the fact that, no, for once he doesn’t have anything to say about it — but, in reality, it’s Blume that’s his soul mate.

It’s a sweet movie with a clear and loving craftsmanship that keeps the tragedy from being too tragic and the comedy from removing it too far from reality. It takes place within a distinct bubble — presented literally as a play — but that’s as it should be. Rushmore is Max’s story, and Max’s story deserves to be told with as much charm and detail and structural obsession as possible.

It’s also Anderson’s story, and an exploration of the results of unchecked control. It makes for a beautiful portrait, but one that needs to be penetrated before you can see the actual human shape that’s being painted.