Vampire Weekend, “Ladies of Cambridge”

B-side, 2007

Maybe I will do a list of this kind every month. Or maybe I won’t. I probably won’t. I hope you didn’t like that introductory paragraph very much, because I’m going to write another one:

Comedy is difficult. Making people laugh is the easy part…making people laugh for the right reasons, at the right times, satisfyingly and consistently, is practically a science. For that reason, we come to expect that not every comedian will make it big, and that not every joke they tell will make us laugh. We know that an impressive hit rate is difficult to maintain, and we adjust our expectations accordingly, striking a balance between how much we’d like to be entertained, and how much we can reasonably expect of a fellow flawed human being.

But, sometimes, a particular comedian is doomed from the start. He is not only incapable of making us laugh, but he’s without control over his material, his audience, or even his demeanor. It’s tragic when this happens, and painfully awkward. The floundering comedian is an effective and offputting archetype, and that’s why writers have dipped into this well repeatedly, crafting characters fated to bomb every time, doomed to botch every punchline, making us laugh not warmly, but defensively, and with discomfort.

In the interesting cases of these comedians, laughing at their material means you missed the joke. Here are 10 examples of that irony personified.

There’s perhaps no better cultural touchpoint for the ill-equipped comedian than Fozzie Bear, and his signature “wocka wocka” has wormed its way into our vernacular as well, becoming rightfully associated with sub-par material and limp gags. Fozzie’s routine was dated before he was born, relying on simple puns and vaudeville showmanship to generate rapturous laughter and applause that never comes. He’s also, however, eminently sympathetic, which is not only why we like him, but why Kermit keeps him around, and gives him another chance every week to die on stage. With two old curmudgeons heckling him from the balcony above, we are free from the desire to criticize his act, and can instead turn our attention to the uplifting fact that no matter how poorly he’s received, Fozzie’s always devoted enough to his craft to throw away what doesn’t work — in his case, everything — and write a whole new act from scratch. We’d love to see Dane Cook follow his lead.

There’s perhaps no better cultural touchpoint for the ill-equipped comedian than Fozzie Bear, and his signature “wocka wocka” has wormed its way into our vernacular as well, becoming rightfully associated with sub-par material and limp gags. Fozzie’s routine was dated before he was born, relying on simple puns and vaudeville showmanship to generate rapturous laughter and applause that never comes. He’s also, however, eminently sympathetic, which is not only why we like him, but why Kermit keeps him around, and gives him another chance every week to die on stage. With two old curmudgeons heckling him from the balcony above, we are free from the desire to criticize his act, and can instead turn our attention to the uplifting fact that no matter how poorly he’s received, Fozzie’s always devoted enough to his craft to throw away what doesn’t work — in his case, everything — and write a whole new act from scratch. We’d love to see Dane Cook follow his lead.

Jimmy Valmer is a special case, in several senses of the word. For one, he’s an 8-year-old boy, which means — unlike Fozzie and everyone else on this list — he isn’t disappointed that he hasn’t made it further in his comedy career. After all, that’s still to come! But he also suffers from several obvious physical handicaps. No matter; Jimmy wants only to make the world laugh, an ambition that’s downright touching by South Park standards, and one made all the more unfortunate by his chronic stutter, which causes him to step on his own punchlines and prevents him from honing his delivery…or even intelligibility. His jokes are about what you would expect from an 8-year-old boy — meaning his material is about as mature as could reasonably be expected and therefore, again, elevates him above the other entries on this list — but they actually seem to work. Stan, Kyle, Cartman, Kenny and the rest of the boys accept him relatively happily for who he is, functioning just fine within their social circle, and he’s not defined in their eyes by his handicaps. No, instead Jimmy is treated exactly as poorly as they treat anyone else. That’s the healing power of humor.

Jimmy Valmer is a special case, in several senses of the word. For one, he’s an 8-year-old boy, which means — unlike Fozzie and everyone else on this list — he isn’t disappointed that he hasn’t made it further in his comedy career. After all, that’s still to come! But he also suffers from several obvious physical handicaps. No matter; Jimmy wants only to make the world laugh, an ambition that’s downright touching by South Park standards, and one made all the more unfortunate by his chronic stutter, which causes him to step on his own punchlines and prevents him from honing his delivery…or even intelligibility. His jokes are about what you would expect from an 8-year-old boy — meaning his material is about as mature as could reasonably be expected and therefore, again, elevates him above the other entries on this list — but they actually seem to work. Stan, Kyle, Cartman, Kenny and the rest of the boys accept him relatively happily for who he is, functioning just fine within their social circle, and he’s not defined in their eyes by his handicaps. No, instead Jimmy is treated exactly as poorly as they treat anyone else. That’s the healing power of humor.

Aziz Ansari is a genuinely gifted comic, and as Parks and Recreation demonstrates weekly, he’s also a talented actor. Both of those things allowed him to bring to life Randy, a pitch-perfect exaggeration — though only just — of a comedian so manic and animated that it completely masks the dire quality of the material he’s delivering. The greatest stand-up comics raised their volume for emphasis. Those from Randy’s school of performing, on the other hand, do it to drown out audience thought, keeping them cheaply engaged and laughing hollowly so that they won’t realize there isn’t any substance. Funny People is just one of many movies that Ansari steals wholesale from their ostensible stars, and the character of Randy has gone on to a have a full life outside the film: Ansari deploys him during his actual stand-up routines now, perhaps as a point of comparison to his normal material, but more likely as a cathartic blow against more popular, more profitable contemporaries of his, who cash larger paychecks but don’t have anything worth saying. Randy may be a popular draw within the world of the film, but all he really does is pull audiences away from more deserving performers.

Aziz Ansari is a genuinely gifted comic, and as Parks and Recreation demonstrates weekly, he’s also a talented actor. Both of those things allowed him to bring to life Randy, a pitch-perfect exaggeration — though only just — of a comedian so manic and animated that it completely masks the dire quality of the material he’s delivering. The greatest stand-up comics raised their volume for emphasis. Those from Randy’s school of performing, on the other hand, do it to drown out audience thought, keeping them cheaply engaged and laughing hollowly so that they won’t realize there isn’t any substance. Funny People is just one of many movies that Ansari steals wholesale from their ostensible stars, and the character of Randy has gone on to a have a full life outside the film: Ansari deploys him during his actual stand-up routines now, perhaps as a point of comparison to his normal material, but more likely as a cathartic blow against more popular, more profitable contemporaries of his, who cash larger paychecks but don’t have anything worth saying. Randy may be a popular draw within the world of the film, but all he really does is pull audiences away from more deserving performers.

In contrast to Randy, Kenny Bania is a hack we actually tend to like. Like Fozzie Bear before him, we feel protective of Kenny Bania, as though we don’t trust that he’ll survive the cruel world of stand-up comedy. Even the typically staid Jerry breaks down his personal barriers and takes Bania under his wing — however temporarily. Bania is overjoyed by the simplest, laziest pieces of observational humor, often interrupting his mentor with a sincere and irony-free exclamation of “That’s gold, Jerry! Gold!” His perpetual enthusiasm and sunniness is a rare thing for the Seinfeld gang, and it’s no wonder that he made several appearances during the show’s run, becoming more successful as a comic, but never getting any better or any wiser. Bania was given the ultimate compliment long after Seinfeld ended, by being one of very few recurring characters resurrected for that show’s “reunion” episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm. Unlike the profoundly irritating Randy, whose success seems to grow as your faith in humanity diminishes, Bania is more of an infectiously adorable nuisance, and it’s nice to know that he’s still out there somewhere, as ecstatic as ever over jokes that aren’t as clever as he thinks they are.

In contrast to Randy, Kenny Bania is a hack we actually tend to like. Like Fozzie Bear before him, we feel protective of Kenny Bania, as though we don’t trust that he’ll survive the cruel world of stand-up comedy. Even the typically staid Jerry breaks down his personal barriers and takes Bania under his wing — however temporarily. Bania is overjoyed by the simplest, laziest pieces of observational humor, often interrupting his mentor with a sincere and irony-free exclamation of “That’s gold, Jerry! Gold!” His perpetual enthusiasm and sunniness is a rare thing for the Seinfeld gang, and it’s no wonder that he made several appearances during the show’s run, becoming more successful as a comic, but never getting any better or any wiser. Bania was given the ultimate compliment long after Seinfeld ended, by being one of very few recurring characters resurrected for that show’s “reunion” episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm. Unlike the profoundly irritating Randy, whose success seems to grow as your faith in humanity diminishes, Bania is more of an infectiously adorable nuisance, and it’s nice to know that he’s still out there somewhere, as ecstatic as ever over jokes that aren’t as clever as he thinks they are.

Krusty the Clown has provided us with much cause for laughter over the years…just not where he wanted us to find it. His Krusty the Clown Show sketches are the stuff of huge mustaches and pie fights, something that might be written by somebody who grew up watching classic comedians, but could never figure out why they were supposed to be funny. In fact, his comedy routines are so poor that they drove at least one of his previous sidekicks to criminal insanity. The humor behind Krusty comes from the incongruity of his situation: he’s a children’s entertainer who openly dislikes children, even when the cameras are rolling. His drug and booze fueled lifestyle allow him to coast lazily through whatever appearances he’s contractually obligated to make, but beyond that he’s a comedian who doesn’t particularly care whether or not you find him funny…he gets paid either way. In fact, in one episode (“The Last Temptation of Krust”) Krusty does become inspired to develop as a stand-up comedian, and achieves a new peak of notability with his more mature, insightful material. And then, of course, somebody offers him money, and he realizes that that’s his real passion. Krusty isn’t a hack because he doesn’t have the talent; he’s a hack because he’d rather make easy money than work hard. It’s an ethos so powerful and seductive that it eventually infected the writing of The Simpsons itself.

Krusty the Clown has provided us with much cause for laughter over the years…just not where he wanted us to find it. His Krusty the Clown Show sketches are the stuff of huge mustaches and pie fights, something that might be written by somebody who grew up watching classic comedians, but could never figure out why they were supposed to be funny. In fact, his comedy routines are so poor that they drove at least one of his previous sidekicks to criminal insanity. The humor behind Krusty comes from the incongruity of his situation: he’s a children’s entertainer who openly dislikes children, even when the cameras are rolling. His drug and booze fueled lifestyle allow him to coast lazily through whatever appearances he’s contractually obligated to make, but beyond that he’s a comedian who doesn’t particularly care whether or not you find him funny…he gets paid either way. In fact, in one episode (“The Last Temptation of Krust”) Krusty does become inspired to develop as a stand-up comedian, and achieves a new peak of notability with his more mature, insightful material. And then, of course, somebody offers him money, and he realizes that that’s his real passion. Krusty isn’t a hack because he doesn’t have the talent; he’s a hack because he’d rather make easy money than work hard. It’s an ethos so powerful and seductive that it eventually infected the writing of The Simpsons itself.

You’d be hard pressed to describe any of the main characters in It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia as sympathetic, but you’d probably have the easiest time with Dee, if only because she seems to be aware that she’s missing out on something greater in the world. For all their grumbling and groaning, Mac, Dennis, Charlie and Frank are all actually pretty content where they are, and with who they are. They don’t have much of a desire to achieve even a measure of self-awareness, let alone anything bigger for themselves. Dee, on the other hand, does have aspirations: she wants to be an actress. With so little experience and talent behind her, though, she isn’t even sure where to begin, which is why she regularly subjects herself to delivering dire stand-up comedy at The Laff House. She explains this to Charlie — the only one in whom she’s confided about her performances — by saying she’s paying her dues. After all, if she wants to be an actress, she has to learn how to hold an audience. Fair enough, but when her set degenerates immediately into a series of painful and repulsive dry heaves, it’s clear that this is a gesture of self-mutilation, rather than any experience she’s likely to benefit from. Charlie, meanwhile, eats cat food. He’s the happier one.

You’d be hard pressed to describe any of the main characters in It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia as sympathetic, but you’d probably have the easiest time with Dee, if only because she seems to be aware that she’s missing out on something greater in the world. For all their grumbling and groaning, Mac, Dennis, Charlie and Frank are all actually pretty content where they are, and with who they are. They don’t have much of a desire to achieve even a measure of self-awareness, let alone anything bigger for themselves. Dee, on the other hand, does have aspirations: she wants to be an actress. With so little experience and talent behind her, though, she isn’t even sure where to begin, which is why she regularly subjects herself to delivering dire stand-up comedy at The Laff House. She explains this to Charlie — the only one in whom she’s confided about her performances — by saying she’s paying her dues. After all, if she wants to be an actress, she has to learn how to hold an audience. Fair enough, but when her set degenerates immediately into a series of painful and repulsive dry heaves, it’s clear that this is a gesture of self-mutilation, rather than any experience she’s likely to benefit from. Charlie, meanwhile, eats cat food. He’s the happier one.

The brilliant third series of The League of Gentlemen found many of its characters being thrust well outside of their comfort zones, an evolutionary direction for the show that resulted in much of its best — if not necessarily funniest — material. For Geoff Tips, this meant leaving the small town of Royston Vasey to pursue a stand-up comedy career in London. This is not a career change that’s destined to go well, particularly as we’ve already seen him botch jokes so badly that he’s threatened to shoot people for not laughing, and play practical jokes on his friends that involve him staging a gory suicide in a restaurant bathroom. Comedy is not Geoff’s forte, but it is his passion, and so, when he loses his job in “Turn Again, Geoff Tipps”, the comedy club is the first place he turns. Of course he bombs in more ways than one, not only allowing his act to dissolve into a shouting match with dissatisfied audience members, but also by serving as the unwitting chauffeur for a terrorist car bomb on behalf of the IRA. Still, you’ve got to laugh, haven’t you?

The brilliant third series of The League of Gentlemen found many of its characters being thrust well outside of their comfort zones, an evolutionary direction for the show that resulted in much of its best — if not necessarily funniest — material. For Geoff Tips, this meant leaving the small town of Royston Vasey to pursue a stand-up comedy career in London. This is not a career change that’s destined to go well, particularly as we’ve already seen him botch jokes so badly that he’s threatened to shoot people for not laughing, and play practical jokes on his friends that involve him staging a gory suicide in a restaurant bathroom. Comedy is not Geoff’s forte, but it is his passion, and so, when he loses his job in “Turn Again, Geoff Tipps”, the comedy club is the first place he turns. Of course he bombs in more ways than one, not only allowing his act to dissolve into a shouting match with dissatisfied audience members, but also by serving as the unwitting chauffeur for a terrorist car bomb on behalf of the IRA. Still, you’ve got to laugh, haven’t you?

Comedy is not GOB Bluth’s strong point. Nor is puppeteering. Nor music. Nor ventriloquism nor respecting the delicacy of race relations. It’s pretty clear then that his act with Franklin is going to go about as well as anything else he’s done. That won’t stop GOB, however, because GOB is one of those people who believes that everything he does is being done well, simply by virtue of the fact that it’s he who is doing it. He sees himself as preternaturally gifted in all areas he attempts to explore, and often this premature self-satisfaction is so seductive that others get sucked in as well. In the case of Franklin Delano Bluth — the puppet who reminds us that it’s not easy being brown — however there’s not much to get on board with. His racially-charged banter with the dead-eyed Franklin is stymied by the fact GOB can’t keep his lips from moving, ultimately resulting in his desperately hiding a tape recorder inside the puppet as a substitute for using his own voice. Unfortunately, GOB’s lips still move, even though he’s not saying anything, and the act is just as doomed as it ever was. As a character, GOB rarely says or does anything genuinely clever; rather, he works so well as a comic figure because of just how artfully he gets everything wrong. And speaking of puppets…

Comedy is not GOB Bluth’s strong point. Nor is puppeteering. Nor music. Nor ventriloquism nor respecting the delicacy of race relations. It’s pretty clear then that his act with Franklin is going to go about as well as anything else he’s done. That won’t stop GOB, however, because GOB is one of those people who believes that everything he does is being done well, simply by virtue of the fact that it’s he who is doing it. He sees himself as preternaturally gifted in all areas he attempts to explore, and often this premature self-satisfaction is so seductive that others get sucked in as well. In the case of Franklin Delano Bluth — the puppet who reminds us that it’s not easy being brown — however there’s not much to get on board with. His racially-charged banter with the dead-eyed Franklin is stymied by the fact GOB can’t keep his lips from moving, ultimately resulting in his desperately hiding a tape recorder inside the puppet as a substitute for using his own voice. Unfortunately, GOB’s lips still move, even though he’s not saying anything, and the act is just as doomed as it ever was. As a character, GOB rarely says or does anything genuinely clever; rather, he works so well as a comic figure because of just how artfully he gets everything wrong. And speaking of puppets…

Of all the characters on this list, Joe Beazley and Cheeky Monkey are the only ones who have just a single appearance to their credit. Even Randy continued to exist outside of the film that gave him life. Joe Beazley and Cheeky Monkey, however, so thoroughly squandered their chance at fame that they were never heard from again, in any form, ever. Just one of many, many, many things to go wrong for Alan Partridge on his ABBA-inspired chat show, Joe Beazley — suffering obvious and debilitating stage fright — bungles his performance so badly than Alan is forced to shut it down almost immediately…much to Joe’s chagrin. Joe starts out by bungling a joke that he improvised just minutes before in the green room, and it only gets worse from there. This comedy misfire wasn’t quite as damaging to Alan’s television career as the fact that he later shot another guest through the heart with a dueling pistol on live television, but the bitter taste of Joe Beazley’s routine with Cheeky Monkey lingers on to this day; he was one of the performers Alan saw fit to call out and specifically berate in his recent memoir, I, Partridge. Alan’s not one to let go of disappointment easily, and this laugh-free puppet fiasco affected him so profoundly that he used it as justification for never again giving up-and-coming performers a break. Ooh, you cheeky monkey.

Of all the characters on this list, Joe Beazley and Cheeky Monkey are the only ones who have just a single appearance to their credit. Even Randy continued to exist outside of the film that gave him life. Joe Beazley and Cheeky Monkey, however, so thoroughly squandered their chance at fame that they were never heard from again, in any form, ever. Just one of many, many, many things to go wrong for Alan Partridge on his ABBA-inspired chat show, Joe Beazley — suffering obvious and debilitating stage fright — bungles his performance so badly than Alan is forced to shut it down almost immediately…much to Joe’s chagrin. Joe starts out by bungling a joke that he improvised just minutes before in the green room, and it only gets worse from there. This comedy misfire wasn’t quite as damaging to Alan’s television career as the fact that he later shot another guest through the heart with a dueling pistol on live television, but the bitter taste of Joe Beazley’s routine with Cheeky Monkey lingers on to this day; he was one of the performers Alan saw fit to call out and specifically berate in his recent memoir, I, Partridge. Alan’s not one to let go of disappointment easily, and this laugh-free puppet fiasco affected him so profoundly that he used it as justification for never again giving up-and-coming performers a break. Ooh, you cheeky monkey.

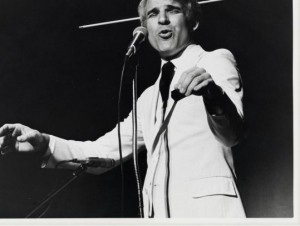

Why are we ending on an actual comedian? Well, because Steve Martin, in terms of his stand-up anyway, was always a very deliberate creation. What you saw on stage wasn’t Steve Martin the man, but Steve Martin the character. His arrow through the head, his balloon animals, his belabored “Well ex-cuu-uu-uuse me!” were all meant as clever pieces of anti-comedy. When he took to the stage, he did so as a walking caricature of the worst that stand-up comedy had to offer. Needless to say, audiences loved it, and Martin was given higher profile gigs, such as a record-breaking number of appearances on Saturday Night Live, and also more classic films than we can remember. The public initially decided they loved Steve Martin because he shined a spotlight on things that weren’t funny, but he did so in such an endearingly committed way that they just had to laugh. And then, once he had everybody’s attention, he showed the world that he knew comedy so well that he’s since stood as an important cultural fixture, spanning decades while lesser comedians — including many who unintentionally resembled the act that made him famous — came and went. And the moral of Steve Martin’s story is the most important lesson to keep in mind here: anyone can write a bad joke, but it takes a sincerely gifted people to craft these characters that are so perfectly bad in all the best ways.

Why are we ending on an actual comedian? Well, because Steve Martin, in terms of his stand-up anyway, was always a very deliberate creation. What you saw on stage wasn’t Steve Martin the man, but Steve Martin the character. His arrow through the head, his balloon animals, his belabored “Well ex-cuu-uu-uuse me!” were all meant as clever pieces of anti-comedy. When he took to the stage, he did so as a walking caricature of the worst that stand-up comedy had to offer. Needless to say, audiences loved it, and Martin was given higher profile gigs, such as a record-breaking number of appearances on Saturday Night Live, and also more classic films than we can remember. The public initially decided they loved Steve Martin because he shined a spotlight on things that weren’t funny, but he did so in such an endearingly committed way that they just had to laugh. And then, once he had everybody’s attention, he showed the world that he knew comedy so well that he’s since stood as an important cultural fixture, spanning decades while lesser comedians — including many who unintentionally resembled the act that made him famous — came and went. And the moral of Steve Martin’s story is the most important lesson to keep in mind here: anyone can write a bad joke, but it takes a sincerely gifted people to craft these characters that are so perfectly bad in all the best ways.

The Farrelly Brothers have been promoting their movie The Three Stooges by saying that first and foremost they wanted to pay tribute to the originals. Well, their movie is out this weekend, and from all accounts it doesn’t sound like all that flattering a tribute.

The Farrelly Brothers have been promoting their movie The Three Stooges by saying that first and foremost they wanted to pay tribute to the originals. Well, their movie is out this weekend, and from all accounts it doesn’t sound like all that flattering a tribute.

Personally, here’s how I’d pay proper tribute. I know it’s complicated, so I’ve tried to break it down into simple steps.

1) Take some time and go through all the surviving Stooge shorts. From these, take about 80 minutes’ worth of the best and most memorable material. You can narrow it down to a few complete shorts, or mix and match sequences from however many you like. I can see pros or cons either way. The important thing is, you’re using the originals, and not some lesser, artless stab at joyless re-creation.

2) Get someone knowledgeable and well-respected in the film industry to record an introduction for you. Roger Ebert won’t do for obvious reasons, but I’m sure you can find somebody important to speak for a minute or two about what the Stooges did for comedy, and how they influenced just about every physical comedian to come. This will be the first thing audiences see, because it’ll be comparatively boring and we want it out of the way early. Allot time for a pie in the face.

3) Draft a bunch of your Hollywood friends and colleagues to record new and interesting linking material. If they were willing to commit to humiliating cameos in the backyard horseplay you call a tribute film, I’m sure they’d be at least as willing to do this instead. Some of them might even come away from the project with some measure of self-respect, which would make for a nice selling point by comparison.

4) Edit it all together into A Celebration of The Three Stooges, or something. I don’t care. Call it a Tribstooge if you want. It doesn’t matter. Just as long as your centerpiece is original material, lovingly restored and considerately presented, featuring sincere reminiscences and discussions by contemporary stars and artists who appreciated them. Release it for one night only, or maybe schedule several showings over one weekend, to spur ticket sales and contribute to an overall sense of being part of an appreciative community.

5) There is no five. There are only four steps. This is fucking easy.

Of course, such a gambit might not make as much money as a major Hollywood film, but it would certainly cost a hell of a lot less than the monstrosity we have instead…and the profits on that one are yet to be determined anyway.

Then again, what do I know? We’re obviously in the hands of capable professionals.

Just a quick post to give a lot of love to Billy’s Gourmet Hot Dogs, for basically just being awesome. Oh, and for opening another restaurant closer to where we live now, even if they had the audacity not to tell us.

Just a quick post to give a lot of love to Billy’s Gourmet Hot Dogs, for basically just being awesome. Oh, and for opening another restaurant closer to where we live now, even if they had the audacity not to tell us.

I’m not exaggerating when I say that Billy’s is the only thing I miss about our old apartment. In fact, between the defecating hobos and gang wars Billy’s was about the only thing I felt comfortable looking at directly. And it was delicious.

My girlfriend and I fell in love with that place soon after I moved in. She’d never been there, despite living right next door, but I changed that. She started making me eat salad, so in an act of supreme revenge I forced her to eat hot dogs. Personally, I think she got the better end of the deal.

Before we moved we bought mugs with the Billy’s logo on them, so we wouldn’t forget their almost criminally perfect hot dogs. (White Hot, I’m looking at you.) But we didn’t need them, because we still go back pretty regularly. It’s worth driving that far. Order the garlic pesto blue cheese fries just once and see if I’m lying.

The service is also fantastic, with Billy himself and Billy Jr. on hand to give out samples, suggest concoctions not on the menu (HELLO, MAC DADDY!!) and just generally be excellent human beings.

We haven’t been to the new location yet, but my girlfriend and I were glad to see that Billy was doing well enough to expand. It couldn’t have happened to a nicer guy.

Also, according to their website they cater. So if you’re getting married, let them make you a shitload of hotdogs. And also invite me.

Because I fucking love these hot dogs.