The law isn’t justice. It’s a very imperfect mechanism. If you press exactly the right buttons and are also lucky, justice may show up in the answer. A mechanism was all the law was ever intended to be.

NOTE: This article is spoiler-free, for those who care about that. How I managed to write over three thousand words about a mystery without spoiling anything is a case I’ll never be able to solve.

There’s something sad about a man losing everything. There’s something even sadder about a man who has nothing finally finding himself with something to lose. It won’t stick around…it can’t stay. The universe can’t let you get away with happiness for too long. At least, that’s the kind of thing Philip Marlowe might think. And by the time we join up with him — toward the very end of a long, cruel and dangerous career — we really can’t blame him.

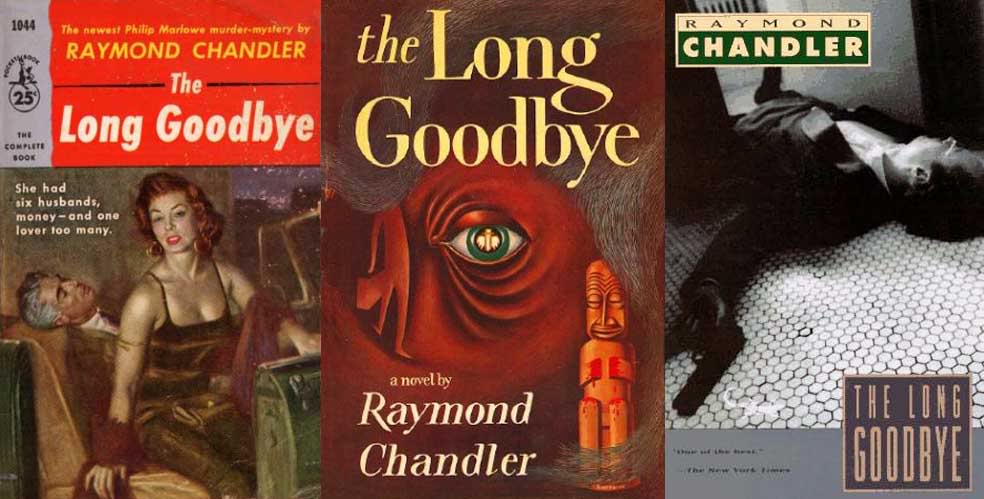

After a few false starts with interchangeable detective figures known as Dalmas and Mallory and Carmady, Raymond Chandler stumbled upon the name Philip Marlowe, and from then forward that was the only name he used. And with a steady name came the benefit of cumulative characterization. World building was not only made easier, it became a sort of passive necessity. And as Chandler plumbed the depths of this character who originated as nothing more than a pawn to be manipulated by the conventions of the genre, he graduated from fictionist to author. Marlowe did that for him. And in return, Chandler allowed his creation to star in some of the most effectively literary experiments detective fiction is ever likely to have.

After a few false starts with interchangeable detective figures known as Dalmas and Mallory and Carmady, Raymond Chandler stumbled upon the name Philip Marlowe, and from then forward that was the only name he used. And with a steady name came the benefit of cumulative characterization. World building was not only made easier, it became a sort of passive necessity. And as Chandler plumbed the depths of this character who originated as nothing more than a pawn to be manipulated by the conventions of the genre, he graduated from fictionist to author. Marlowe did that for him. And in return, Chandler allowed his creation to star in some of the most effectively literary experiments detective fiction is ever likely to have.

But while Chandler’s star was on the rise, Marlowe’s was on an eternal decline. The long-suffering private detective was regularly insulted, beaten, stabbed, shot, brained, double crossed, left for dead and rejected by the world around him. And yet, like Charlie Brown and the football, he never gave up. Something kept Marlowe moving forward. Something stopped him from turning in his license and going to work in a hardware store — an alternate existence he ponders here in The Long Goodbye. Something compelled him to press on with his thankless job that would no doubt, in time, get him killed. And that something was an unflagging sense of justice.

For Marlowe, justice and the law are two separate entities that occasionally overlap, but are no substitutes for one another. The quote that opens this article comes from Sewell Endicott, a well-meaning but easily manipulated lawyer, but his observation echoes Marlowe’s own philosophy. The laws are rules that only really work to keep people in line who don’t press against them — in other words, they are only really of use to those who wouldn’t break them. For everybody else, there needs to be a different kind of justice. There needs to be a super-legal vigilance that punishes and redresses “wrong,” as opposed to “illegality.” That vigilance is missing from this world. Marlowe figures — more or less correctly — that it will either come from himself, or from nowhere. And so he slips a gun into his pocket, dons a fedora, and hopes nobody will notice last night’s black eye. It will kill him, but justice is larger than he is. The world can live without Philip Marlowe, but it can’t — or shouldn’t — continue on without somebody keeping the cosmic moral compass in check.

The police, interestingly, are often portrayed as Marlow’s biggest adversary. While he goes up against gangsters and thieves and thugs and murderers nightly, he knows what to expect from them. They make no convincing overtures that they are anything but villains, and Marlowe simply has to keep himself from getting killed until he finds an opening to bring them down. The police, on the other hand, claim to want the same thing he wants; they just have a different method for achieving it. Their method has the force, their method has the reach, and their method has the power. They are a national, well-organized and infinitely funded resource. Marlowe is a quiet man standing sour-faced in the rain. The former sees success when they close out a case…regardless of the accuracy of its outcome. Marlowe’s success is a more difficult, less quantifiable result: justice. He doesn’t always know how he’ll get there, or what it means, but he knows he’ll recognize it when he finds it.

Sewell Endicott is a prime example of what frustrates Marlowe about the legal process. He’s a good person who genuinely wants to see a case closed correctly. He follows proper procedure and asks all of the questions he is supposed to ask. However when placed up against those who know how to respond to those questions in such a way that satisfies Endicott but leaves the truth buried, he’s helpless. Marlowe sees this. The case is closed. The murder is solved and the murderer has been brought to some kind of justice. Only Marlowe doesn’t buy it. Something doesn’t fit. Endicott asks all of the questions he is supposed to ask. Marlowe endangers his own life by asking everything else. That’s the difference.

Or, rather, a difference. Marlowe’s sense of right and wrong is his own…a hyper-personal arbitration by which we are all judged, separate from and alternately looser and stricter than the more tangible “law.” Philip Marlowe is Chandler’s Ozymandias. The ends for him always justify the means, as he withholds evidence, obstructs and often derails the judicial process in aid of some grander, more solvent statement that will have a wider-reaching and fairer outcome than a standard criminal investigation ever could. And as with Ozymandias, a lot of innocent people get hurt along the way.

Or, rather, a difference. Marlowe’s sense of right and wrong is his own…a hyper-personal arbitration by which we are all judged, separate from and alternately looser and stricter than the more tangible “law.” Philip Marlowe is Chandler’s Ozymandias. The ends for him always justify the means, as he withholds evidence, obstructs and often derails the judicial process in aid of some grander, more solvent statement that will have a wider-reaching and fairer outcome than a standard criminal investigation ever could. And as with Ozymandias, a lot of innocent people get hurt along the way.

When I started reading Chandler a few years back, I thought I knew what to expect. And, in a way, I did. Detective fiction is a comparatively rigid genre. It has its rules and it wears them on its sleeve. Very rarely does detective fiction aim to achieve anything beyond a satisfying mystery cleverly resolved. And, in fact, that’s what Chandler was providing throughout an enormous portion of his career. Writing stories of about fifty pages each gave him just about enough room for a setup, a twist, a gunfight and a resolution. Along the way he might have stumbled over interesting characters or dynamics, but there wasn’t any time to explore them. That’s part of why, beginning with The Big Sleep, his first novel, Chandler turned back to his old stories…combining and manipulating and deepening them. It’s not that he didn’t know how to flesh out a novel, it’s that he had already written novels that were confined to 50 pages each, and wanted now to give them some breathing space. Going from 50 pages to 300 gave him a lot more room to explore these situations and these characters and their motivations. And going from one novel to an entire series gave him exponentially more room to explore Marlowe, and to test his unwavering morality against temptations of all kinds: personal, financial, carnal…and, in The Long Goodbye, devotional.

The Long Goodbye is Chandler’s final major work starring Philip Marlowe. It’s also, without question, my favorite of Chandler’s writings. Coming as it does toward the end of Marlowe’s career, the accumulated impact of tragedies lends this book an intriguing sense of weariness. Marlowe’s compass is as accurate as ever, but his body is broken. His drive is slowing down. His world view is stained permanently by the blood of the past. All of this is to say that Marlowe, here, is weaker than he’s ever been. Which allows him to make his ultimate mistake: befriending another human being.

Yes, The Long Goodbye is a story of friendship, much like previous spotlights Double Indemnity and “AWESOM-O.” But in this case the friendship is much more to the forefront, and is, in fact, the driving force behind the entire novel. In fact, it may even be the driving force behind everything Marlowe says and does this time around. His characteristic — and highly personal — morality is still on display, but it sometimes takes a back seat to the devotion and loyalty he has for his friend, Terry Lennox.

It’s easy to see why Marlowe feels so drawn toward Terry Lennox. He first meets him outside of an expensive club, where Lennox is first rejected and then physically removed from his own vehicle by the woman he’s with. He’s drunk, he’s broke, and he’s abandoned. The woman, his ex-wife Sylvia, drives off without him, and the doorman leaves him to lie embarrassingly on the pavement. Marlowe sees him there, scarred up from an old war injury and left to rot on streets that will never care whether he lives or dies, and he lifts him up. He takes him home. He sees himself in Lennox…a hopeless case that will never learn, but one with a good heart. As the novel unfolds, we learn that the disfiguring injury was actually the result of a wartime sacrifice, as he allowed himself to be nearly killed by a detonating shell so that his squadron might live. Marlowe slowly begins to feel accountable for Lennox. Nobody else will so much as speak to him, but Marlowe takes him home, joins him regularly for drinks, and eventually even allows the man to take him into his confidence about his history…something Marlowe typically avoids specifically so that he won’t develop a human connection.

It’s easy to see why Marlowe feels so drawn toward Terry Lennox. He first meets him outside of an expensive club, where Lennox is first rejected and then physically removed from his own vehicle by the woman he’s with. He’s drunk, he’s broke, and he’s abandoned. The woman, his ex-wife Sylvia, drives off without him, and the doorman leaves him to lie embarrassingly on the pavement. Marlowe sees him there, scarred up from an old war injury and left to rot on streets that will never care whether he lives or dies, and he lifts him up. He takes him home. He sees himself in Lennox…a hopeless case that will never learn, but one with a good heart. As the novel unfolds, we learn that the disfiguring injury was actually the result of a wartime sacrifice, as he allowed himself to be nearly killed by a detonating shell so that his squadron might live. Marlowe slowly begins to feel accountable for Lennox. Nobody else will so much as speak to him, but Marlowe takes him home, joins him regularly for drinks, and eventually even allows the man to take him into his confidence about his history…something Marlowe typically avoids specifically so that he won’t develop a human connection.

Friendship is new to Marlowe. In several novels, including this one, he has a mutually antagonistic relationship with Bernie Ohls, the only cop Marlowe consistently respects, but they clash over their methods and can’t entirely allow the other to be too satisfied with what they’re doing. This, one begins to feel, must be the only friendship Marlowe is comfortable with: one that simply will not come too close. Marlowe and Ohls are chained to separate posts. They might be able to pull themselves near enough to interact, but never will they share the same world. And that’s how Marlowe likes it, preferring to spend his nights alone in a rented room solving a book of chess problems than out with anybody who may eventually double cross him. As Bob Dylan would later observe, “When you ain’t got nothing, you’ve got nothing to lose.”

And Marlowe’s right to be so reticent, because everybody will double cross him. It’s what he’s learned…or, rather, it’s what the world has taught him. Nobody gets away with being happy for too long, and Marlowe, who has never allowed himself to be happy, seems to have skirted that tragedy with a loophole. By living in rented rooms and never allowing himself to indulge in human relationships, there is nothing for anybody — or anything — to take away from him. When he lets Terry Lennox in, he is opening the door to his own tragedy.

And sure enough, tragedy does strike. Lennox shows up at Marlowe’s home early one morning, and demands that he gets driven to Mexico. Marlowe takes him on the condition that Lennox doesn’t tell him why; if he knows a crime has been committed, he won’t morally be able to help him escape. While this is true to the technicality of Marlowe’s ethical bent, it’s a completely deliberate fudge; an intentional exploitation of a logistical blindspot. In short, it’s exactly what Marlowe dislikes about standard policework, and it’s our first clear indication that his devotion to Lennox has managed to supplant — or at least uproot — Marlowe’s guiding morality. We let it happen here in the real world, too…any time we allow our feelings toward our friends, or relatives, or spouses or children to take precedence over how we might otherwise behave without them. It’s what happens when we start to make decisions based on how other people might feel. For us, it’s a necessary and often rewarding part of adulthood. For Marlowe it’s a liability, and a failure on his part to sustain his integrity in a crime-laden universe.

Marlowe later learns that Sylvia is dead, bludgeoned horribly by a small bronze statuette, and almost completely unidentifiable. He goes to jail for several days where he is beaten and abused by his fellow agents of the law, but refuses to tell them anything about Lennox, or where he’s gone, or whether or not he might have been involved. He is released only when it is learned that Lennox has committed suicide in a hotel room in a small Mexican town. Case closed.

But for Marlowe, it isn’t over. The Long Goodbye uses the Lennox material as bookends. He may be dead, but the novel still has several hundred pages left to go, and as the title suggests, letting go of his old friend won’t be easy.

But for Marlowe, it isn’t over. The Long Goodbye uses the Lennox material as bookends. He may be dead, but the novel still has several hundred pages left to go, and as the title suggests, letting go of his old friend won’t be easy.

The first Philip Marlowe novel was The Big Sleep, whose title was a euphemism for death. It’s fitting then that the title of the final major work featuring Marlowe refers to the process of mourning. It also, though not by design, reflects the long goodbye we as readers are saying to Marlowe. The slight Playback is the only complete story he will feature in after this one, and that’s a much shorter goodbye, a brief and airy swansong that leaves little impact in the wake of the sprawling Long Goodbye that preceded it. Poodle Springs, the novel meant to follow that up, was never completed.

Letting go of his dead friend is further complicated by the letter Marlowe receives, which was mailed before the suicide and contains a note of appreciation and a $5,000 bill. Marlowe doesn’t spend it. He’s back to his old self, eschewing personal gain because he knows it will eventually lead to personal loss. He downplays the value of the bill by referring to it as a portrait of Madison.

But he’s a changed man. The impact of having had a friend — or, perhaps, the impact of having lost one — has left a different, more sentimental Marlowe in his place. In Lennox’s letter he asks Marlowe to remember him by preparing a cup of coffee and a cigarette…which is what they last shared before Marlowe brought him to Mexico. He also asks that Marlowe return to their favorite tavern and drink a gimlet on his behalf. Marlowe does the former almost immediately, but turns down many opportunities for the latter. He knows, after all, that once he does so, he will have finished his goodbye. He will have to come to grips with the fact that Terry Lennox is no more. He will have to come to grips, that is to say, with the fact that the one friendship we’ve ever known him to have no longer exists.

There’s a lot more in The Long Goodbye than what I’ve mentioned so far. There’s the long and difficult case of the Wades, of course, and there’s the gorgeous central chapter in which Marlowe, for once, narrates a simple day at the office. But it’s all a symptom of his fatigue. He refuses to become embroiled in the evolving tragedy of Roger and Eileen Wade, and his dour recitation of a dull workday’s worth of meaningless encounters just serves to underscore the hollowness he feels.

The Wade interlude — like the titular goodbye, it’s a long interlude — occurs between the two halves of the Lennox case. In fact, the structure of the novel is artfully chiasmatic: the Lennox setup, the Wade setup, the glorious middle section that features Marlowe being reflective (in more ways than one, natch), the Wade conclusion, and finally the Lennox conclusion. Such deliberate craftsmanship in a genre not famed for complex artistic flourishes comes, probably not coincidentally, in a novel that features an author character who questions his value to the literary world, when all he writes is easily-digestible pulp. Wade cannot escape the sense that he’s capable of more. Chandler reaches just a little further, and achieves it.

The Wade interlude — like the titular goodbye, it’s a long interlude — occurs between the two halves of the Lennox case. In fact, the structure of the novel is artfully chiasmatic: the Lennox setup, the Wade setup, the glorious middle section that features Marlowe being reflective (in more ways than one, natch), the Wade conclusion, and finally the Lennox conclusion. Such deliberate craftsmanship in a genre not famed for complex artistic flourishes comes, probably not coincidentally, in a novel that features an author character who questions his value to the literary world, when all he writes is easily-digestible pulp. Wade cannot escape the sense that he’s capable of more. Chandler reaches just a little further, and achieves it.

It’s also no coincidence that the woman Marlowe will eventually marry makes her first appearance in this book. This is the right time for him; he is at the crux of a major change, as Terry Lennox — the only and last pillar of humanity he believed in — is torn bloodily from his life. It’s not so much that Linda Loring comes along and Marlowe recognized his future in her, it’s that Marlowe needed direction and Linda Loring came along.

It is, however, a coincidence that Chandler died during the composition of Poodle Springs, the novel which would feature Marlowe as a married man, secure in a different kind of existence with a companionship and stability he never knew…and, indeed, as the novel was unfinished, would never get to know. Just another cosmic insult to the private eye, one last kick in the pants and assurance that, yes, it is your destiny to be abused and, yes, we will see to it that you never escape.

Knives and bullets and bats and fists never managed to break Philip Marlowe, but the friendship of another man did. And Marlowe, without having anything else in his past worth comparing it to, does not know how to cope. He keeps digging up dirt and second guessing details. The case is closed, Marlowe. Everything is over and people are happy. Please leave it alone.

But he doesn’t. Because something is missing. He may have had and lost an important friendship, but he wasn’t double crossed. He wasn’t used or abused or manipulated by the person that he foolishly let into his life. And for that reason, he knows it can’t be over. And he digs, and he fights, and he argues, all in the service of uncovering the truth of the betrayal of which he knows he must have been the victim.

It’s a bizarre and unsettling psychological subversion of the genre Marlowe once represented so cleanly. He is driven by the unscripted forces of right and wrong, compelled onward by a sense of justice nobody else on the planet seems to share or even understand. Typically this means he seeks to bring the bad guys down. In The Long Goodbye, however, he is fighting to become the victim himself. Everything is quiet, and everything worked out…and that’s impossible, because Philip Marlowe hasn’t been obviously betrayed. He hasn’t paid the price for violating his rule of human contact. And he won’t rest until he finds his wounds and rubs them raw. He will not stop until he’s forced himself to feel the pain he knows he must have earned. His compulsion toward justice has morphed gradually into a kind of self-abuse, a cycle of internal torment that Marlowe — in just about every way apart from the literal — won’t survive.

It’s a bizarre and unsettling psychological subversion of the genre Marlowe once represented so cleanly. He is driven by the unscripted forces of right and wrong, compelled onward by a sense of justice nobody else on the planet seems to share or even understand. Typically this means he seeks to bring the bad guys down. In The Long Goodbye, however, he is fighting to become the victim himself. Everything is quiet, and everything worked out…and that’s impossible, because Philip Marlowe hasn’t been obviously betrayed. He hasn’t paid the price for violating his rule of human contact. And he won’t rest until he finds his wounds and rubs them raw. He will not stop until he’s forced himself to feel the pain he knows he must have earned. His compulsion toward justice has morphed gradually into a kind of self-abuse, a cycle of internal torment that Marlowe — in just about every way apart from the literal — won’t survive.

He suffers for justice, justice of any kind, any where, for any one, please, just somewhere let justice shine, let the wrong be punished and let the right be relieved, just once, please, before I die…and yet, when he finds it, he must simply begin again, with a new case, resetting the counter, as though the previous events never happened…yet retaining the scars it took him to get there. Once that sense of justice is turned inward, there is nothing he can do but self-destruct.

It’s a lot darker and more emotionally complex than I ever expected detective fiction to be, and it comes at — more or less — the very end of Marlowe’s career both as a private detective and as a character. I thought I knew what to expect. I thought Chandler was just going to give me another volume of entertaining and distant tragedy, trimmed and packaged for my approval.

I wouldn’t say it’s one of my favorite books, but I will say it was one of my favorite experiences as a reader, and I’m still not sure I know what to do with it. To paraphrase one of Marlowe’s observations about cops, just when I thought I knew what to expect, one of them had to go and get human on me.