He’s metal and small and doesn’t judge me at all.

He’s a cyberwired bundle of joy.

My robot friend.

In 2004, a coworker of mine convinced me to start watching

South Park again. I’m not really sure why I had stopped. I was one of the show’s early adopters — which isn’t saying much; there were many — and I was always happy to defend it as being more substantial than its mountains of violence and profanity led the easily insulted to believe. It was a great show, I thought, with clever writing and some genuinely intelligent insight into touchy subjects and controversial material. But at some point, probably around season five or so, it became less important for me to tune in regularly. I think, in a way, I didn’t want to watch it become a shadow of itself. I never saw the quality slip, but my turning away was a preemptive measure. It’s what would keep me from having to see it devolve and degrade itself before me, becoming less of an artistic statement and more of a way of keeping Comedy Central swimming in merchandising profits as the years went on.

But my coworker assured me that that hadn’t happened. That South Park was just as good as it ever was, or probably even better. So I tuned in for the first time after a long absence, and watched each new episode of season eight as it premiered. And though the kids were all the same age and the adults were no wiser, South Park as a show revealed to me just how much it managed to grow up.

The self-imposed tight turnaround on South Park episodes sounds like a living nightmare when you hear creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone talk about it in interviews, and often that fatigue shows in their responses to the interviewers’ questions. They sound careless and dismissive. They don’t seem particularly invested or enthusiastic. But it works wonders in terms of keeping the show fresh — note I’m saying nothing about topicality — and I think that’s the reason it glides so smoothly along to this day, periodically achieving greatness sixteen seasons on.

Why do I think this brutal tightness of schedule might be a facilitator of quality? Well, because of “AWESOM-O.” And because of many, many other things that this episode leads me to think about.

In the week leading up to the premiere of “AWESOM-O,” Comedy Central ran promos promising the return of Lemmiwinks. Lemmiwinks was the gerbil from the deservedly popular “The Death Camp of Tolerance” episode from two seasons prior, and while I could understand why they’d think fans would appreciate a callback to that episode, I wasn’t quite sure why I was supposed to be getting excited about another episode centering around the sexual insertion of rodents. But then the night came, and there was no Lemmiwinks. Instead we got a title card, explaining that due to the recent tragedy in Hawaii, that episode would not be aired, and we would get something else instead. That something else was “AWESOM-O.”

In the week leading up to the premiere of “AWESOM-O,” Comedy Central ran promos promising the return of Lemmiwinks. Lemmiwinks was the gerbil from the deservedly popular “The Death Camp of Tolerance” episode from two seasons prior, and while I could understand why they’d think fans would appreciate a callback to that episode, I wasn’t quite sure why I was supposed to be getting excited about another episode centering around the sexual insertion of rodents. But then the night came, and there was no Lemmiwinks. Instead we got a title card, explaining that due to the recent tragedy in Hawaii, that episode would not be aired, and we would get something else instead. That something else was “AWESOM-O.”

“AWESOM-O” is easily one of my favorite episodes of South Park, and I could fill another post by simply listing the reasons for that. It’s also, apparently, the episode with the fastest turnaround time in the show’s history: three days from conception to air. That means that when the Lemmiwinks episode vanished, they didn’t just air a rerun, or slap up something else that was ready to go. They built something from the ground up, a ramshackle creation of whatever they could get their hands on quickly, much in the same way Cartman must have constructed his robot costume. There was no tragedy in Hawaii. They just made it most of the way through the process of producing an episode that it turned out they didn’t believe in. And rather than just finishing it and shipping it off to air and be forgotten, they stopped. They had the courage to throw it away, and to begin again. With a deadline looming and nothing to show for the work they’d already invested, it was up to them not only to replace an episode in the lineup, but qualitatively justify the fact that they had thrown a different one away.

That’s something that few shows have the luxury of doing, and it’s why South Park is able to continue to feel fresh: in a very literal way, it always is.

A show like The Simpsons — which was beginning to show its age not long after South Park shuffled into view, and was well past its prime by the time South Park gave us “AWESOM-O” — has a turnaround time of around six months per episode. That means that by the time all the pieces are put together, it’s too late to do much corrective work. Even if the entire creative staff is unsatisfied with the way the pieces fit, little more than polish can be applied. The episode, as it is, six months after the final script was written and recorded, is airing whether you like it or not. South Park, fortunately, never had anywhere near that turnaround. Parker and Stone started off with Comedy Central working at a frantic pace and never stopping to catch their breath, and that’s the way it remains today. It means the two of them don’t get much sleep and often feel as though their creation is eating them alive, but it also means that if they produce an episode that they don’t like, they can destroy it and start fresh. They are in the habit of doing so, they have a production style that was built to sustain such changes in trajectory, and there isn’t half a year and several million dollars invested. Ironically, the tighter time frame and smaller budget allow the South Park crew to do more than shows with more bountiful resources.

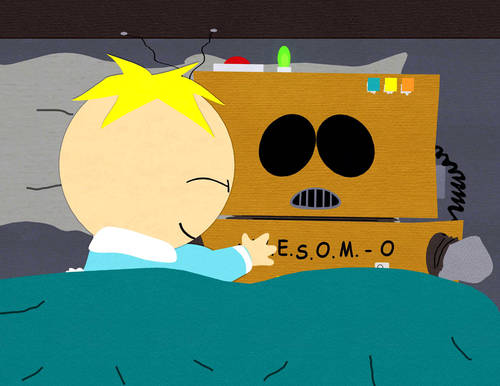

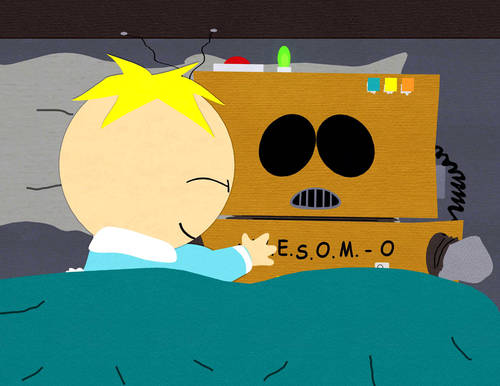

As a last-minute substitute, “AWESOM-O” makes perfect sense. The germ of the idea (Cartman dresses like a robot to play a prank on Butters) is simple. It doesn’t require much thought to flesh it out; it’s an episode where kids behave like kids, making it a good fit for the characters, and also an easy night in the writers’ room. There’s no need for topical jokes or complicated inversions of established tropes; this is a chance for two of the show’s most popular characters — and, arguably, the show’s single most fruitful dynamic — to take center stage and entertain us.

As a last-minute substitute, “AWESOM-O” makes perfect sense. The germ of the idea (Cartman dresses like a robot to play a prank on Butters) is simple. It doesn’t require much thought to flesh it out; it’s an episode where kids behave like kids, making it a good fit for the characters, and also an easy night in the writers’ room. There’s no need for topical jokes or complicated inversions of established tropes; this is a chance for two of the show’s most popular characters — and, arguably, the show’s single most fruitful dynamic — to take center stage and entertain us.

It’s also, however, a brilliant little character piece, offering both Cartman and Butters the chance to display emotions they don’t often get to tap into. It’s a small story that could have taken place entirely in Butters’s bedroom, but its themes are powerful and universal. “AWESOM-O” is a story of friendship, like Double Indemnity before it. And like Double Indemnity, it’s a story of underhanded dealings, dubious motives, and the climactic disappointment of the piece’s only innocent man.

Cartman decides — off camera, for reasons we never hear — to play a prank on Butters, and it’s his most cutting and personal one yet: by pretending to be a robot, he’s going to let Butters believe that he has a friend for life, and then take that friendship away from him.

For comparison’s sake, two of Cartman’s previous pranks on Butters are recounted in this episode: he once locked him in a bomb shelter for several days, and he imitated Butters on the phone so that his father would come home and beat him. Either of those pranks sounds significantly crueler than the helpful robot persona Cartman adopts here, but a step back reveals that that’s not the case; either of the other two pranks would have worked just as well on any of the other children. There’s nothing about either of them that target Butters as an individual…he’s simply a victim, and might as well be anonymous. Here, however, Cartman is preying on something he knows Butters — and only Butters — will respond to in the necessary tragic way: a friend. For any other child, friends come and go. Betrayal is unfortunate, but not uncommon. In order for someone to be betrayed, however, there must be a relationship to betray, and Cartman knows that Butters has never had that. He will befriend the boy for the sole purpose of breaking his heart. It’s the most hurtful thing Cartman can do to Butters, and so of course he can’t resist.

Of course Cartman’s plot falls apart the moment he finds out Butters has blackmail material on him: a videotape of him dressed as Britney Spears and dancing with a cardboard cutout of Justin Timberlake. Butters doesn’t intend to blackmail him, and in fact doesn’t even remember where the videotape is, but once Cartman learns of it existence he’s unable to reveal himself, and is therefore unable to break Butters’s heart. He is, instead, forced to become and remain the actual friend that he was going to make Butters look foolish for believing in.

You’ll notice that there’s nothing about Stan, Kyle or Kenny in the above discussion, and that’s because they’re relegated to cameos here. They show up to wonder why Cartman is still keeping his robot ruse going, but, technically, that scene didn’t even need to be there. They serve no purpose as characters, and the script doesn’t try to force them in where they don’t belong.

I noticed this when I watched it new, way back in 2004, and it’s just a broader reflection of why the tight schedule works so well for this show: with no time to lose, Parker and Stone are used to throwing away ideas that don’t work, and shifting directions at a moment’s notice. It’s an approach borne of utility, but in a larger sense it works in the show’s favor, as it’s conditioned them not to hold fast to what no longer interests them for the sake of maintaining status quo.

I noticed this when I watched it new, way back in 2004, and it’s just a broader reflection of why the tight schedule works so well for this show: with no time to lose, Parker and Stone are used to throwing away ideas that don’t work, and shifting directions at a moment’s notice. It’s an approach borne of utility, but in a larger sense it works in the show’s favor, as it’s conditioned them not to hold fast to what no longer interests them for the sake of maintaining status quo.

If you think I’m going to bring up The Simpsons again as a point of comparison, you’re right. After all, there’s no better reference point for either of the two shows than each other, and whereas The Simpsons has been recycling plots and echoing itself in gradually deteriorating whispers for the sake of remaining familiar to whatever small audience still chooses to follow it, South Park has been ditching characters and ideas since season two, scrambling up core dynamics and introducing new regular characters in order to explore avenues that they previously couldn’t reach without stretching characters beyond their scope of believability.

Compared to the early seasons of South Park, “AWESOM-O” seems like an almost completely different show. It looks and sounds the same, but so many staple features have been abandoned in the meantime. Chef doesn’t sing an inappropriate song, Kenny doesn’t die, Kyle doesn’t learn something today, Stan has been ousted as the central figure by a previously unnamed background character we now know as Butters, the town doesn’t riot, and no grand observations are made about politics, religion or society. Officer Barbrady and the Mayor don’t exist anymore, Mr. Garrison no longer speaks through Mr. Hat, Ike doesn’t show up for a round of Kick the Baby and Randy Marsh has gone from “Stan’s dad” to breakout character. Things have changed, and the show let them change.

This is a simple story of a boy and his robot friend, and it’s a thousand miles removed from anything the show laid the groundwork for in its early years. The reason? That groundwork proved limiting and was growing tiresome, and so the creators chose to evolve rather than to stagnate. It was a wise decision. After all, despite what any network executives might think, it’s not the familiarity that keeps people tuning in…it’s the quality. Lose familiar elements and an audience might stick around, but lose the quality and you’re finished for good.

The promotion of Butters to main character status is probably one of the most fruitful changes the show ever made. It was a sacrifice of familiar elements made in favor of maintaining quality, and it allowed them to write the kinds of stories that were previously off-limits. After all, Butters is a different type of child…one that was not represented within the main group. Stan was logical and well-centered, Kyle was the moralist, Cartman was the asshole, and Kenny was…well, Kenny was several things, but outside of a few grand exceptions (like his Mysterion arc) he was simply crude. They were all distinct characters, as you can see, but none of them were at all fragile. In fact, that’s what won over audiences — and infuriated parents — when the show premiered: these kids didn’t take any shit. The cursed, they fought back, and they were perfectly capable of resorting to things we never thought we’d see children do on primetime television.

The promotion of Butters to main character status is probably one of the most fruitful changes the show ever made. It was a sacrifice of familiar elements made in favor of maintaining quality, and it allowed them to write the kinds of stories that were previously off-limits. After all, Butters is a different type of child…one that was not represented within the main group. Stan was logical and well-centered, Kyle was the moralist, Cartman was the asshole, and Kenny was…well, Kenny was several things, but outside of a few grand exceptions (like his Mysterion arc) he was simply crude. They were all distinct characters, as you can see, but none of them were at all fragile. In fact, that’s what won over audiences — and infuriated parents — when the show premiered: these kids didn’t take any shit. The cursed, they fought back, and they were perfectly capable of resorting to things we never thought we’d see children do on primetime television.

Butters, however, does none of that. He is fragility incarnate. Easy to hurt, and yet always willing to get back up and let you hurt him again. He doesn’t have a malicious bone in his body, and he is endlessly selfless and caring. He’s neither rude nor profane (he blurts out “Oh hamburgers,” when he’s particularly upset), and he just wants everyone around him to be happy. This makes him an excellent foil for the boys in general, but especially, of course, for Cartman in particular.

Cartman doesn’t just get annoyed by Butters as the other boys do…he actively wishes to harm him. In Cartman’s world, there is no room for a Butters. It is impossible to co-exist…the fact that Butters is fragile and helpless is a clear-cut reason that he must be destroyed.

Butters, on the other hand, sees the boys — and, again, particularly Cartman — as his friends. He must; without ever having had actual friends to compare them to, he assumes that these boys who talk to him must qualify. It doesn’t matter how badly they mistreat him, or how callously they abuse him…Butters sees them as friends. Which is why “AWESOM-O” is interesting. Cartman assumes that Butters has never experienced friendship…despite the fact that he himself is often on the receiving end of Butters’s declarations of loyalty.

But he’s right. What Butters has with AWESOM-O is different, and even Butters must feel that on some level. At first, he’s just another friend. But once he listens to what Butters has to say, helps him with his chores and engages in social activities with him in public — all things his other “friends” never did — Butters knows that this is really what friendship is supposed to be, and he falls for it. Hard. Listen to the wistful way he sings the word “friend” in the song quoted above; there’s an enormous gravity hanging from that tiny word…a large investment of emotion that, previously, had nowhere to go. And when AWESOM-O asserts himself and expresses desires contrary to what Butters now expects of his friend, there’s a telling moment during which Butters scolds him, and even resorts to physical violence: a spanking. He has a friend now…and he’s not going to let him get away.

But he’s right. What Butters has with AWESOM-O is different, and even Butters must feel that on some level. At first, he’s just another friend. But once he listens to what Butters has to say, helps him with his chores and engages in social activities with him in public — all things his other “friends” never did — Butters knows that this is really what friendship is supposed to be, and he falls for it. Hard. Listen to the wistful way he sings the word “friend” in the song quoted above; there’s an enormous gravity hanging from that tiny word…a large investment of emotion that, previously, had nowhere to go. And when AWESOM-O asserts himself and expresses desires contrary to what Butters now expects of his friend, there’s a telling moment during which Butters scolds him, and even resorts to physical violence: a spanking. He has a friend now…and he’s not going to let him get away.

I don’t know precisely what it was about “AWESOM-O” that made me like it so much at first, and what still causes it to resonate with me today. Maybe it’s the writing-workshop approach to the script, the alchemy of pressing deadline pain into gold. Maybe it’s the fact that it’s a small, human story instead of some grander, topical plot. Or maybe it’s just something simple: the small satisfaction of seeing Cartman on the losing end for a change, and watching him struggle to reverse that, as his prank backfires and he’s stuck in an endless premise with no conclusion. The plan was to give Butters a taste of friendship and then take it away, but he’s unable to progress past step one, and the joke’s on him: like or not, he really did become Butters’s friend. As the scientist observes at the end of the episode, it doesn’t matter if AWESOM-O is a robot; what matters is the very human spirit of friendship it brought to the boy who loved him. Of course the scientist believes Cartman to actually be a robot when he says that, but it rings true for the eight-year-old boy inside the cardboard suit as well: whatever Cartman’s motives, it felt sincere to Butters. And that made it real.

“AWESOM-O” might not be what you’d think of when defining a South Park plot, but it’s a perfect fit for the universe created by Parker and Stone. After all, at its best, South Park has always been about the characters rather than the situations. That’s why most viewers, when asked about their favorite episodes or highlights, will tend to point toward smaller scenes or moments or interactions than any broad celebrity caricature or townwide apocalypse. And the show is still, another eight seasons after “AWESOM-O” premiered, finding new and impressive ways to let those characters be themselves, and find their voices, and live their lives. The Simpsons, at its best, was also about its characters, but that show is no longer anywhere near as interested in letting them be themselves. What made The Simpsons so brilliant is that they started with a palette of stereotypes, and layered and explored those characters until they felt like real human beings. What unmade The Simpsons was that, at some point, they destructively stereotyped them again, and left them there.

I don’t know what the Lemmiwinks episode was supposed to be about. Perhaps I would have loved it. That doesn’t matter.

What matters is that the creators weren’t pleased with it. They took a long hard look at what they accomplished, and they made a difficult decision: to throw it away, and to try harder.

It’s an interesting coincidence to me that this episode was part of South Park‘s eighth season, as I’d say that the eighth was the last truly great season of The Simpsons. From season nine on, it was a slope that got more slippery all the time, and now, I’d argue, it’s no longer even interested in climbing back up again. South Park was poised at that precise point three days before “AWESOM-O” aired. Would they take the easy way out and just air some mediocrity, and hope that the show would fix itself in the future? Or would they keep working until they had something worthy of carrying the reputation that they’d built?

It’s an interesting coincidence to me that this episode was part of South Park‘s eighth season, as I’d say that the eighth was the last truly great season of The Simpsons. From season nine on, it was a slope that got more slippery all the time, and now, I’d argue, it’s no longer even interested in climbing back up again. South Park was poised at that precise point three days before “AWESOM-O” aired. Would they take the easy way out and just air some mediocrity, and hope that the show would fix itself in the future? Or would they keep working until they had something worthy of carrying the reputation that they’d built?

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, and South Park could not travel both. It took the road less traveled by.

It chose not to follow the path to ruin and creative bankruptcy. After all…Simpsons did it.