It’s interesting to note that just a couple of years ago, “I like Ghostbusters” would be about as benign (and common) a statement as one could possibly imagine. Now it’s fraught with inference, with baggage, and with controversy.

That’s because, until very recently, the word “Ghostbusters” meant a movie. Or maybe that movie and its sequel. Or maybe some toys. Or maybe a spinoff cartoon. With the release of a gender-swapped third film, however, the conversation shifted embarrassingly. This is to say nothing about that third film’s quality, or merits, or actual issues. It’s just to say that prior to that film’s release (or, I suppose, announcement), a conversation about Ghostbusters went one way. Now it inevitably goes another.

We’ll waddle into that whole minefield later, but I bring it up here because, at some point, the new film’s fallout seemed to taint the original’s reputation. Not in any substantial or successful way, but once the rebooted Ghostbusters started receiving mixed reviews and less-than-stellar box office returns, a number of its defenders deflected.

“It’s not like the original was all that great anyway,” they suggested. One film critic that I otherwise respect (and who I’m choosing not to link to, lest this be seen as a kind of bullying) even resorted to cheap snark to say that people were looking back far too fondly on a glorified toy commercial in which Dan Aykroyd gets fellated by a ghost. (In the frantic rush to be within the first fifty thousand people to make that observation, I guess, he managed to get every detail in it wrong.)

This was odd to me. Of course, I’m somebody who refuses to believe that a subpar sequel, remake, or adaptation dispels the magic of the original. Arrested Development season four was awful, but it doesn’t change the amount of respect I have for seasons one through three. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory was a thoroughly worthless re-adaptation of a classic, but the version starring Gene Wilder is no less available for its existence. And I have an entire series dedicated to celebrating both halves of the novel-into-film equation, however successful or not the process was.

I’m used to keeping my opinion of one thing separate from another, however closely those two things might be related. In fact, I don’t even find it that difficult. The prequels didn’t ruin the original trilogy; they just crammed a bunch of unwelcome shit into the lore. Big deal.

In this case, though, folks were actively trying to tarnish the original, and I don’t get it. Likely there was some element of bitterness there, and I can understand that, to some degree. When you enjoy something so many others vocally do not, it’s easy to feel alone. But to then try to tear down something that they enjoy…well, that’s not an especially admirable response.

Especially when it’s outright false. I watched Ghostbusters repeatedly as a child, and have seen it many times as an adult as well. I rewatched it this very afternoon so that I could write this article, and I can say that it’s an excellent movie. It’s funny. It’s clever. It’s profoundly well-acted. It was deservedly popular and massively influential. For my money, there hasn’t been another sci-fi comedy that holds a candle to this one. (Though Back to the Future is almost certainly the closest.)

Trying to sully the reputation of Ghostbusters is something that, quite simply, isn’t worth the effort. You’ll have no chance of succeeding, and you’ll only look foolish by trying to point at and mock something that’s actually damned good. Every one of us grew up loving something that by no means stands up to the scrutiny of adult eyes. Ghostbusters, though, isn’t one of those things.

It’s probably difficult to imagine just how big this movie was if you weren’t there to experience it. I was three when it was released, but Ghostbusters (or “Ghost Busters,” as it’s oddly spelled on the title screen and seemingly nowhere else) remained a huge presence throughout my entire childhood.

We played with the toys, watched the cartoon, drank the Hi-C. We played the terrible video games. We rewatched this movie and its sequel endlessly. We pretended we were the Ghostbusters on the school yard. I don’t remember what ghosts we thought we were busting, but I do remember that I was always Egon. If our friend Jen was around, she had to be Janine. We never had a Winston.

The fact that a film released in 1984 would retain its relevance and staying power through a good portion of the 90s isn’t unprecedented, but it is exceedingly rare. Ghostbusters took everybody by surprise, though. The movie about some goobers from Saturday Night Live saving the world from a Sumerian god was actually…good. Critics enjoyed it. The public loved it. It pulled in around ten times its $30 million budget.

Nobody knew what to expect of Ghostbusters, but once it caught on, there was no doubting its impact. As Peter Venkman put it, “The franchise rights alone will make us rich beyond our wildest dreams.”

In fact, much of the film seems to reflect its own history and reputation. Coincidentally, I’m sure, but Ghostbusters for long stretches works almost as an allegory for its own creation.

In the film, Ray Stantz puts a third mortgage on his house to get the Ghostbusters off the ground. Throughout the movie, money is an issue, with a take-out Chinese meal representing “the last of the petty cash.” But the team keeps plugging away at their dream, believing in themselves when literally nobody else will. By the end of the film, crowds of fans are chanting their names, crying out for their attention, and hawking bootleg Ghostbusters t-shirts. The seemingly foolish investment up front pays for itself (at least) ten times over.

Then there’s the team itself, which seems to come together out of happenstance. Peter, Ray, and Egon are academic colleagues who all find themselves suddenly without funding and unemployed. They don’t start the Ghostbusters because they want to, but because they have nothing else to do and might as well. They find a secretary, Janine, because she’s the only one who can put with them. They hire Winston Zeddemore because he needs a paycheck at exactly the same time they need another set of hands.

The way the team grows and expands out of necessity mirrors, just about, the way roles were originally written for other actors. John Belushi, John Candy, Paul Reubens, and, according to some sources, Eddie Murphy. Even the way they build themselves up as a brand –- with a firehouse headquarters that, according to Egon, “should be condemned” and a secondhand ambulance that barely runs –- reflects the way the Ghostbusters script was rewritten: a legend was born of budgetary constraints.

Aykroyd, who would go on to play Ray, wrote the original script on his own. At some point, Harold Ramis, who would go on to play Egon, made it clear that the script as written was far too ambitious and expensive for any studio to actually film. (Which makes Ramis seem, amusingly, like the same kind of cold logistician Egon is.) Together, Aykroyd and Ramis rewrote it. Aykroyd is an enormously talented and very funny man, but I think it’s safe to say that we only know and remember Ghostbusters today because Ramis got involved.

I don’t know if Aykroyd’s original script has ever surfaced, but it evidently involved the Ghostbusters traveling through time and around the world to battle some kind of massive paranormal force. Maybe it would have been great, but Ramis reined him in, restricting the entire plot to the city of New York, relegating the elaborate, centuries-spanning supernatural context to a few bits of spoken backstory, and spending time, instead, on the far-less-expensive interaction between characters.

Logistics are often a great curator. If you can’t actually film your original idea, you have to ask yourself what you can do instead, and what might actually work better. You’re essentially forced to come up with a stronger concept. Aykroyd and Ramis certainly did, and the final film balances the fantastic and the practical beautifully.

It also balances a humorous approach with a human one. There are jokes in the movies — and great ones — but not reality-breaking sight gags or slapstick. The jokes work in tandem with the narrative of the film, and the characterization, rather than serving as intermissions from it. Both aspects work together. It’s a comedy, and it’s a sci-fi film. It works either way, but neither half would work anywhere near as well without the other.

This succeeds, to be blunt about it, because the comedy stays where it belongs. The humor almost never comes from the otherworldly danger unfolding in the city. That is to say, the plot isn’t funny; the characters are. Ghostbusters knows better than to cross the streams.

That’s a wise move, because it means audiences can stay invested even while they’re laughing. It also means that the relatively long stretches between jokes don’t feel dull or out of place. They’re part of the movie. Ghostbusters is one of those rare comedies that’s so rightly confident in itself, it can afford to take its time between punchlines. (Which, I’d argue, makes the punchlines we eventually get feel even funnier.)

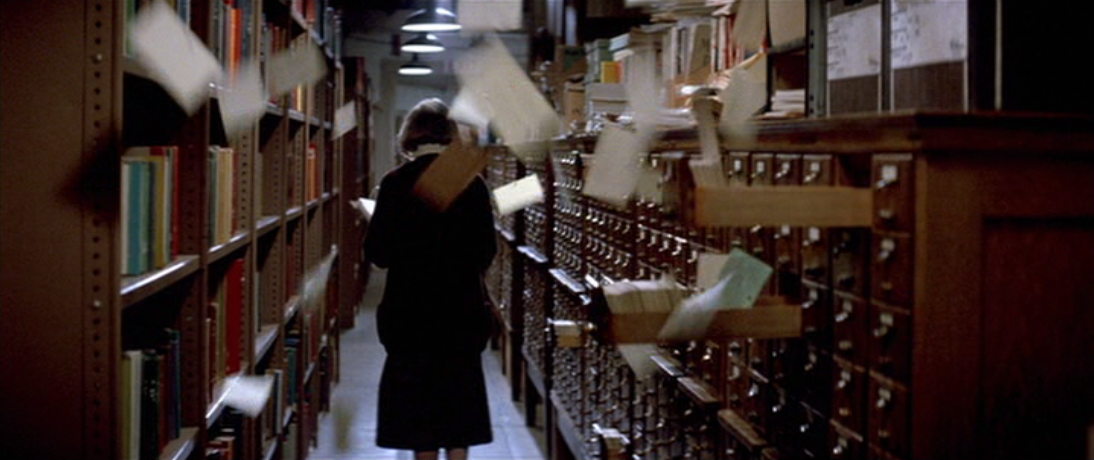

We can see this illustrated by the film’s very first scene, in which a librarian encounters a ghost in the stacks. Abnormally for a comedy, there are no jokes at all in the scene that introduces Ghostbusters to the world. Most comedies, understandably, would work hard to open with a strong or memorable comic setpiece. After all, shouldn’t audiences be laughing?

Ghostbusters replies, “Not necessarily.” Aykroyd and Ramis knew that if there were anything funny about our initial experience with the film’s central threat, it would become that much less threatening, and throw off the tonal balance. If the library ghost is a humorous figure, that makes it far harder to believe that Dana Barrett is in any danger when she’s seized and possessed by demons later in the film. Going for a cheap and easy laugh here must have been tempting, but it would have hamstrung many pivotal moments later on.

Instead, we watch the librarian as she goes about her work. Some books hover from one shelf to another. Cards are spewn from the drawers of a catalogue. Then, in a panic, she turns a corner and finds herself face to face with something so horrifying, she screams and collapses.

What a hilarious movie!

Of course, what this scene is really doing is setting up the comedy to come. The librarian’s encounter with the ghost isn’t played for laughs, because that’s being saved for when our heroes encounter the ghost. Again, it’s not the situation that’s funny; it’s the characters.

We see things first from a normal citizen’s perspective. We get a sense of why people would panic and call somebody like the Ghostbusters. (Technically they aren’t Ghostbusters yet, but you get the idea.) We understand why someone would be desperate to get this dealt with as quickly as possible, by whomever could possibly handle it. If this scene were played for laughs, we wouldn’t be able to identify with that feeling. When we return to the library with our heroes in tow, however, the comedy naturally opens up…at the same time we get to learn about the characters.

Bill Murray, Dan Aykroyd, and Harold Ramis feel immediately like associates who have known each other for a long time. They have an established dynamic. That’s why Peter can tease Ray or drop a book on the table to interfere with Egon’s readings. They know who he is, and they know that this is how he behaves.

By continuing to work with him they are making it clear that they’re okay with his behavior, which is why at no point in the film does anyone shout at him to back off. If his behavior were unwelcome, as it certainly is to other characters and in other contexts, it wouldn’t be as funny. Instead, this is a group of friends. They like him. We learn a lot about them from their interactions.

And, indeed, he plays an important role in the group, though it’s not one that’s immediately obvious. For the audience at home, Peter Venkman gets the lion’s share of the laughs, and that’s reason enough to keep him around. But what does he bring to the actual Ghostbusters?

Egon is quite clearly the brains of the operation. He’s extraordinarily knowledgeable, resourceful, and insightful. It’s easy to conclude that he’s the one who creates (or at least develops) their equipment, and while he lacks basic human social skill, he’s the most innately valuable member of the team.

Ray brings the enthusiasm…and the money. He’s the excitable boy who purchases the firehouse so he can slide down the pole, and who is so thrilled by his new job that when Peter is slimed by a ghost, he first expresses joy…and then asks, “Can you move?” Late in the film, Peter explicitly refers to Ray as “the heart of the Ghostbusters.”

What Peter brings is less obvious, but no less important. If Egon is the brain and Ray is the heart, Peter is the swagger. Dana becomes quickly aware of this, telling him as they investigate her apartment, “You don’t act like a scientist. You’re more like a gameshow host.”

But they need that as well. Peter’s the one who giddily convinces Ray toward the beginning of the film to go into business for themselves. He’s the one who gives interviews to the press and works the crowd. He’s the one, surely, who gets them to produce a television commercial. It’s probably not correct to say that he craves attention, but he’s certainly the only one who knows what to do with it.

The characterization is wall-to-wall one of Ghostbusters’ strongest aspects. I’d argue that it’s stronger here than in almost any other comedy, and than most other films in general.

Every character, the moment he or she is introduced, is established firmly. This applies most obviously to the Ghostbusters themselves. Ray’s introduction is all oblivious giddiness. Egon’s reveals both his deep intelligence and his propensity to get lost in the experiment. (On the time he tried to drill a hole in his own head: “That would have worked if you hadn’t stopped me.”) Winston’s sets him up as a hired gun; a day laborer who will do whatever needs doing without any strong feelings about it one way or the other.

Peter’s introduction is the most elaborate of them, and rightly so, as he’s the only one of the main four with a true character arc. The others essentially end where they start in terms of who they are, but Peter goes from repeatedly administering electric shocks to a volunteer just to flirt with another (if you haven’t seen the film, well…just watch it) to taking his work so seriously that he is willing to sacrifice his life to save others. (He’s the one who decides that they will cross the streams to defeat Gozer…something that reliable Egon promises will have “a very slim chance” of survival.)

But the characterization goes further than that. It extends to every other character as well, no matter how minor. There’s the beleaguered and stressed-out mayor of New York City, who is clearly in an unwinnable situation but genuinely wants to do well by his constituents. There’s Walter Peck, who steels himself behind his own presumed authority and immediately finds himself locked in eternal posturing with Peter.

There’s the stuffy hotel manager who is desperate to have our heroes clear out an infestation, but simultaneously desperate to keep his guests from knowing what’s going on. Hell, there’s the guy waiting for an elevator in that same hotel who doesn’t quite believe the Ghostbusters’ limp cover story that they’re exterminators. And there’s the maid who nearly becomes the first test subject for their proton packs, and who we can see in the background putting out the resulting fire with her squirt bottle.

Everybody feels real. Not one of these characters, however minor, however silly their scene, feels like a caricature. And because of that, they all feel as though they matter. Absolutely nothing in the film feels like padding, however tangential to the plot something is, or appears to be.

I honestly think my favorite moment in the entire film is when an unnamed coachman witnesses the early stages of Louis’ possession and sums it up with a simple, “What an asshole.”

It’s funny, but it’s not a punchline. It’s a very human response to a very extraordinary event, and that’s where Ghostbusters truly succeeds. It successfully funnels a vast supernatural catastrophe into a real-world setting, and shows us how real people would react to it…whether it’s those who fight back, those who dismiss the danger, or those who just watch it unfold.

The human focus isn’t accidental. (In fact, it could be a deliberate creative response to the time-hopping excess of the original script.) One of the biggest surprises rewatching the film as an adult is how little we see of the busting of ghosts. True to the title, the movie is actually about the Ghostbusters…not ghost busting.

There’s the library scene at the beginning, of course, but the only things that get busted are their egos. Later there’s the long hotel sequence during which they capture the ghost we’ll eventually know as Slimer. There’s a montage that includes some busting interspersed with press appearances. And finally they battle Gozer.

That’s not much, and it means that nearly everything else is human interaction. People being people. Colleagues being colleagues. Antagonists antagonizing. There’s actually very little in the way of plot, but a hell of a lot in the way of defining and exploring character.

Okay, well, it’s not entirely fair to say there’s little in the way of plot. There’s honestly quite a lot of it. It never feels that way, however, because of the way it’s parceled out.

Peter shares some of his notes with Dana outside Carnegie Hall. Egon gets a possessed Louis to open up about Gozer’s intentions. Ray pores over architectural blueprints in jail and explains his findings. Winston takes a quiet moment, driving at night, to connect what he’s seen and heard lately to a passage in Revelation.

These moments and a number of others occur throughout the film. Never once is a character tasked with delivering a long-winded monologue explaining what’s happening to the other characters or to the audience. Instead, the data points are scattered like breadcrumbs. If you care enough to follow them, you’ll come to a greater understanding of the specifics behind what, exactly, the Ghostbusters are beating back. (And, I’d wager, what we would have seen in Aykroyd’s original script.)

If you don’t, however, the film doesn’t feel any emptier. In fact, I’ve seen Ghostbusters several dozen times throughout the course of my life and I still couldn’t explain to you the supernatural backstory. What’s more, I don’t care. That’s not what the movie is to me.

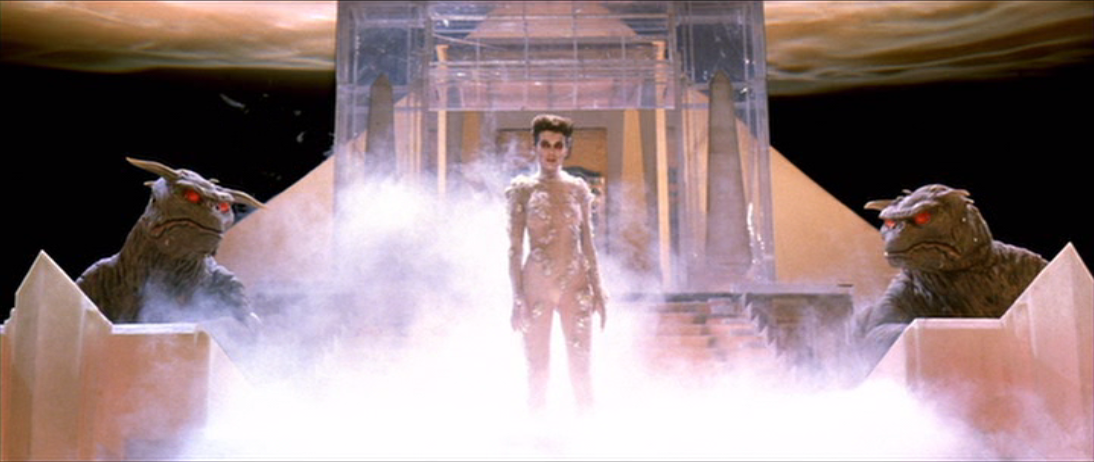

I see a comedy about four misfits ultimately taking down a great and rising evil. Does it matter to me who Gozer specifically is? Or the role of Ivo Shandor, a completely unseen character, in bringing Gozer back? Or why lesser ghosts are able to terrorize New York City before Gozer is able to break through? Or why Dana and Louis are specifically chosen to host Zuul and Vinz Clortho, Gozer’s Gatekeeper and Keymaster? Or how, exactly, the two of them fucking brings Gozer back?

None of this matters to me. If it does to you, that’s great; you’ll have plenty to dig into and enjoy and think about after the film ends. But it all happens in the background. As in Her, or Shaun of the Dead, we see a potential collapse of civilization occur from an artfully, deliberately limited perspective. Bigger things are happening, but we can only see what our characters see. The rest is inference and assumption.

That limitation seems to have been Ramis’ most significant tweak, and it’s the reason those who care about the lore and those who don’t can enjoy the film equally. To paraphrase Winston, If I’m laughing I’ll believe anything you say.

So, okay, clearly I enjoy the acting, the dialogue, the way the characters interact. But I’d be lying if I said a big part of the appeal — both then and now, for myself and for audiences in general — weren’t the spectacle.

I don’t know that I was ever afraid of the ghosts, to any degree, as a kid. Which surprises me to think about now, as I was definitely a wimp when it came to scary things. The earliest nightmares I remember were brought on by Little Shop of Horrors and a commercial for Aliens. (Coincidentally starring the Keymaster and the Gatekeeper, respectively.) I think it’s safe to say I scared easily. But nothing in Ghostbusters actually registered as frightening at all.

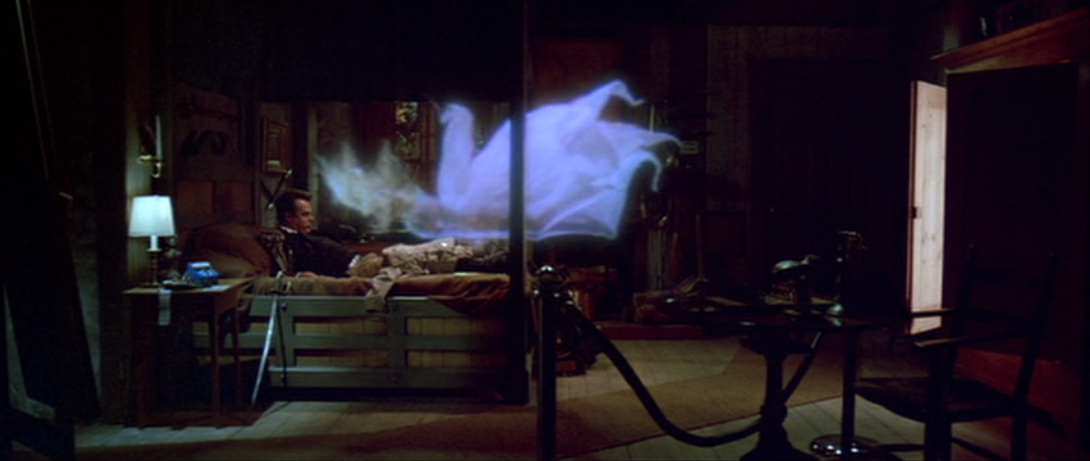

Looking at the film now, though, there are a number of pretty chilling moments. Certainly the most effective is when Dana is grabbed from within a chair and dragged screaming into her bedroom, a sequence which plays as straight horror and is only indirectly undercut by comedy, when Louis is pursued by the same kind of creature in an expressly humorous way. Then there’s the undead taxi driver, who actually does look pretty scary…but he’s only on the screen for a few seconds and doesn’t do anything especially horrific.

Regardless, if I wasn’t afraid of anything in the film, it certainly wasn’t due to unconvincing effects. In fact, by and large they hold up pretty well today. That’s impressive for a silly comedy filled with sketch comedy stars.

Nearly all of it still looks fantastic. The proton streams maybe didn’t age that well, and certain things like the devil dog (as we called them then) crushing Louis’ table don’t seem to be properly integrated, but the stumbles are absolutely the exceptions. The ghosts still look great, with Slimer leaving ectoplasmic residue on the wall he flies through being a notable highlight. The librarian ghost at the beginning looks and behaves in an impressively frightening way.

And to this day, I don’t know they pulled off the effect of the eggs popping and cooking on Dana’s countertop. I’m sure it was a heated surface, but how did they get the eggs to explode the way they did so that their contents would land in the right place to be cooked? There are other objects on the countertop that aren’t being warped from the heat, so it must have been a fairly precise target.

It’s also interesting to me that the Ghostbusters really do just bust ghosts. They fight them, they capture them, they lock them away in what is essentially a prison cell. No thought is given at any point to why these ghosts are haunting these particular locations (though in at least a few cases, environmental details can help us piece together a story).

The boys give no thought to what the ghosts want, or to the fact that helping them resolve their earthly business might allow them to move on to peaceful rest. If memory serves, I do think the cartoon spinoff got into this a number of times, but here, I find it amusing that these guys find evidence of the paranormal and immediately set about beating the shit out of it. (It’s not for nothing that Peter’s triumphant gloating after catching Slimer is, “We came, we saw, we kicked its ass!” They didn’t outwit it; they ganged up on it.)

I could go on for another few thousand words about what makes Ghostbusters work as well as it does. I haven’t even really dug into the three major supporting characters yet.

There’s Dana, played by Sigourney Weaver (who we’ve seen here before). She’s given relatively little to do aside from play the straight man to Peter, and that’s a bit of a shame, but she does it well. (And, if memory serves, she’s given quite a bit more to do in the sequel. We’ll find out next week.) She also functions as an audience surrogate for a brief period, seeing the Ghostbusters’ commercial and being passively amused by what is clearly a scam, before having to rely on them when something inconceivable happens to her. (Their slogan — “We’re ready to believe you!” — turns out to be an accidental bit of marketing genius.)

I also very much enjoy the perfectly acted moment after she shares her story with Egon. His announcement — “She’s telling the truth. At least she thinks she is.” — understandably upsets her; she’s been through a traumatic situation. And yet it’s clearly the correct thing for Egon to assess first.

The fact that the gadgets she’s hooked up to are revealed to be little more than a homemade polygraph upsets her, and that’s a very human response. But Egon is not thinking of her feelings, or of the human element at all. He’s determining whether or not there’s anything to investigate in the first place.

The fact that he then turns to Peter and shines his headlamp into his colleague’s eyes, ignorant of Peter’s reaction, further illustrates how detached Egon really is. It’s a sight gag, but it’s also characterization.

Weaver is also incredible — and worrying — as the physical manifestation of Zuul…equal parts seductive and terrifying in her performance, pivoting in a moment from one to the other.

Then there’s Louis, played by the consistently delightful Rick Moranis. Louis is the humorous counterweight to the serious Dana. Everything she goes through, he experiences the comic version of.

She’s seized by demonic claws and dragged screaming into the clutches of gods-know-what; he gets chased through the streets of the city and eventually, in a panic, offers the creature a Milk-Bone. The moment of her possession is played strictly for horror, while his is played as physical comedy, with Louis sliding helplessly down the glass wall of a restaurant while witnesses refuse his cries of anguish and return to their meals. (That, by the way, is still one of the most perfectly, effortlessly cruel bits of dark comedy I’ve ever seen…and it’s perfectly in keeping with the thematic danger New York City finds itself in for the sequel.)

Even their possessed states are handled differently. Dana’s is actually scary and upsetting; Louis’ is jokey. He tries talking to a horse. He asks strangers if they’re the Gatekeeper. He imitates Egon’s words and gestures during testing not to be a pest, but because he’s like a child seeing these things for the first time.

We’re worried for Dana, but we’re laughing at Louis. That sounds wrong, but both sides of that coin are handled exactly right for what they are.

Then there’s Annie Potts, who may actually be the film’s secret MVP. As a kid I didn’t think much of her character, but as an adult she’s deeply relatable. Like Winston, she’s there because she needs a paycheck. But for her, it really is just a job…and she hates it as she would any job. She’s underpaid. She’s alternately underutilized and overworked. She doesn’t even especially seem to find the fact that her bosses are fighting actual ghosts interesting.

And that’s intrinsically funny!

Not as obviously funny as the gang wrecking up a grand ballroom, or a gigantic marshmallow stomping through the city, or Peter investigating Dana’s apartment. (Asked if he’s using his tools correctly, he hesitatingly replies, “I think so.”) And so her role in the comedy went right over my head as a boy. But now that I’ve worked a number of soul-destroying jobs, as well as jobs I should have liked but which sucked the life out of me because they’re still jobs…yeah. I get Janine.

Also, I love that she acts and dresses like she’s about 60 when Potts was only in her early 30s.

Mainly, though, I love that every single one of her lines plays like a perfectly delivered joke. Some of these are obvious, but others I’m not sure I picked up on before now. When a policeman arrives at the firehouse for instance, she asks, “Dropping off or picking up?” As a kid I just assumed Louis’ case wasn’t isolated; other possessed folks must have changed hands back and forth between the Ghostbusters and the police. Now, though, I see that she was asking if the Ghostbusters were being arrested, and making it clear that this would neither surprise nor disappoint her.

It’s subtle, it’s funny, and it’s perfect.

Honestly, I’m not sure how easy it would be to identify things in Ghostbusters that don’t work. I guess there’s the ghost blowjob bit, but that’s brief. What’s more, it’s a dream sequence, so all the folks who think Ray got fellated by a spirit need to learn to pay attention for more than a few frames of film. Otherwise, nothing really falls flat for me, and any joke that doesn’t get a laugh is either surrounded by good enough acting or followed quickly by something that does.

The ending, I’ll admit, feels abrupt to the point that it seems to come from another movie. Gozer is defeated and…that’s it. I adore Winston’s euphoric “I love this town!” but that’s really the end of the movie?

The film we watched, as we discussed, wasn’t actually about Gozer. It wasn’t about ghosts. It wasn’t about the end of the world. It was about people. It was about how these people relate to each other, and how they deal with an impossible fight against unknowable adversaries. It was about how people interact, how they see the world, and how the Ghostbusters find a place for themselves.

But the ending seems to suggest that the movie was about Gozer, and it thinks that once Gozer is stopped, there’s no story left to tell.

We confirm that all of the major characters are okay, Dana and Peter kiss, and the Ghostbusters drive off. I don’t know what kind of resolution I would have expected, but “Hey, that supernatural thing we never fully explained is gone forever now” wasn’t it.

It’s a small complaint, and it does absolutely nothing to interfere with how enjoyable the ride is, but it feels like it should be the ending to Aykroyd’s original script as opposed to Ramis’ rewrite.

I suppose we can read a bit of narrative closure into that ending. The Ghostbusters start the film losing their funding because nobody takes them seriously, and end it being celebrated by cheering strangers who recognize them as saviors. That’s fine. But the team’s journey toward acceptance wasn’t the focus of the film; it was one of many things that unfolded largely in the background. For the movie to end there, it feels…misjudged.

Again, though, that also feels like a reflection of Ghostbusters’ own creation and legacy. An idea that was doomed to go nowhere gradually finds acceptance. Gets a shot at a wide audience. Finds fans that tell their friends. Eventually sees itself heralded as important, as brilliant, as a part of the world that we can’t imagine going without.

Ghostbusters might be the clearest example of lightning in a bottle that I can point to in the film world. Everything comes together to work perfectly. The writing, the acting, the casting. The directing. The special effects, the soundtrack. The cinematography. The pacing, the editing, the set construction, the props…everything is exactly right. It may not be the funniest comedy I’ve ever seen, but I’d unquestionably put it on my list of the best ones. No part of the film turned out as it was initially envisioned, but all of it was exactly as it should be.

In just over an hour and a half, Ghostbusters introduced so much instantly identifiable iconography to our cultural landscape. It wasn’t just a movie people liked, or which made money…it was a movie that mattered.

It gave us the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man. It gave us Slimer. The Ecto-1. The firehouse. The theme song. The logo. The uniforms, the proton packs, the ghost traps, the containment unit.

Ghostbusters gave us a world that intersected with our own and enriched it. It left us knowing who these characters were, what they wanted, and how they’d each go about getting it. It spun a tale too complex for most of its fans to understand, and yet made sure that that didn’t even matter.

It gave us a touchpoint. Something we’d all relate to. The reason we played Ghostbusters in the schoolyard wasn’t just because we liked the film, but because we knew everybody would understand it. It became instantly as recognizable as cowboys and Indians. And our parents were just as likely to find the film funny and entertaining as we were, even if we enjoyed different parts of it.

A sequel was more or less inevitable. In fact, it was practically obligatory. The Real Ghostbusters cartoon debuted in 1986, two years after this movie, and was immediately popular. It found a fanbase of its own and funneled those fans back to the original film. The cartoon was supported by an equally popular toyline. Tie-ins came in all media. The world wanted more Ghostbusters, and was willing to throw money at anything bearing the name.

In 1989, we finally got our second Ghostbusters film. I remember being overcome with excitement, and it was one of the first films I saw I theaters.

Next week, we’ll find out if it was worth waiting for. But even if it wasn’t, whatever dips and dives the franchise might take from here, the only important to thing to remember is that the original Ghostbusters still exists.

And it’s still fantastic.

That will never change.