With our other two films this year, the YouTube personalities behind them had clear areas of expertise. For James Rolfe, it was video games. For Red Letter Media, it was films. In each case (in different ways), the films they made used that expertise as their creative focus.

That made sense, however successful or not the end results might have been. Now we have Ashens, and…what is Ashens?

I suppose I could also ask “Who is Ashens?” There’s an easy answer to that, though: Ashens is Stuart Ashen, a Norwich-based…humorist? Technology buff? Author?

Okay, I take it back; that answer is not much easier.

Let’s start at the beginning.

In my review of Angry Video Game Nerd: The Movie, I laid out a hypothetical pitch for a television version of the YouTube show Technology Connections. It was, of course, hilarious. My point was that it would have been impossible to get a show with such a loose format made.

Ashens is even looser.

The most universal description of Ashens videos I can provide is this: They take place in front of his brown sofa. There are exceptions to this rule, and plenty of them, but we’ve got to start somewhere.

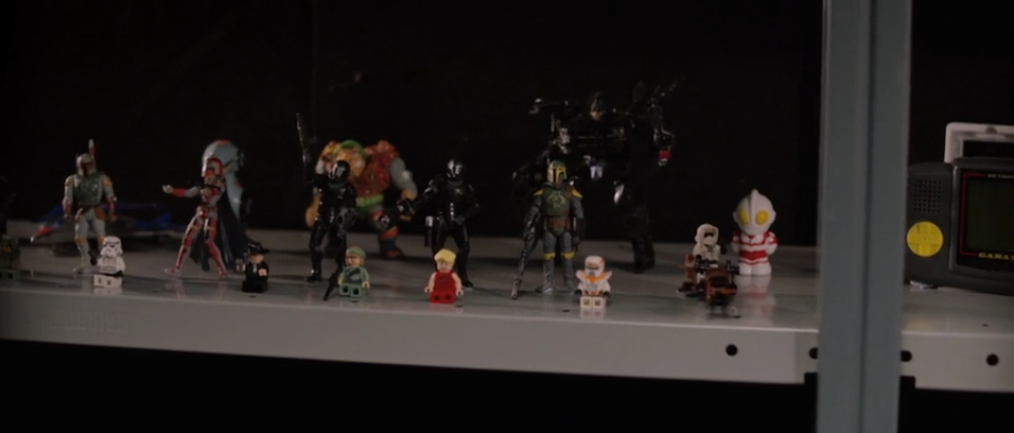

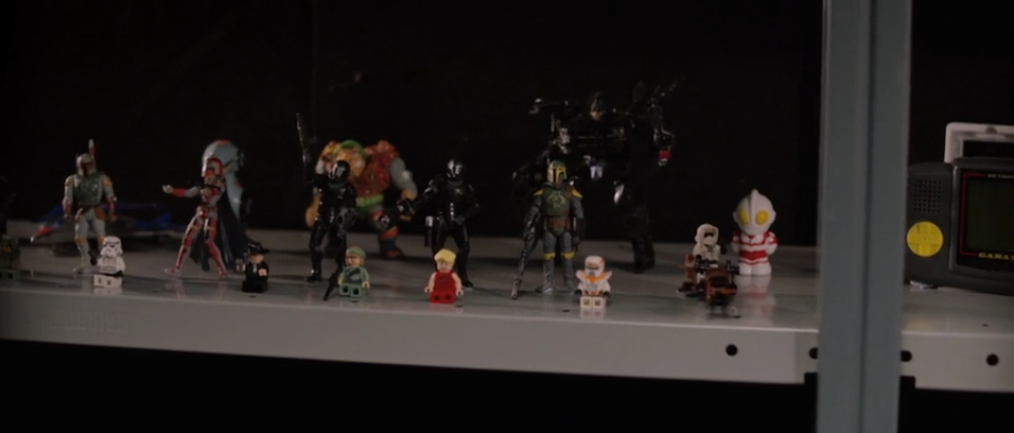

What Ashens does in front of his brown sofa will vary. He could talk about films. He could show off old action figures. He could eat expired food that people sent him in the mail. He could discuss old electronics, new electronics, rare electronics, or famous electronics.

It’s a weird channel, in a sense, as the only constant is Stuart Ashen himself. (“ashens” was a handle born from his surname and his first initial, and it’s since become recognizable as his brand. From here on, I’ll use Ashens to refer to his character in the film and Ashen to refer to…Ashen.)

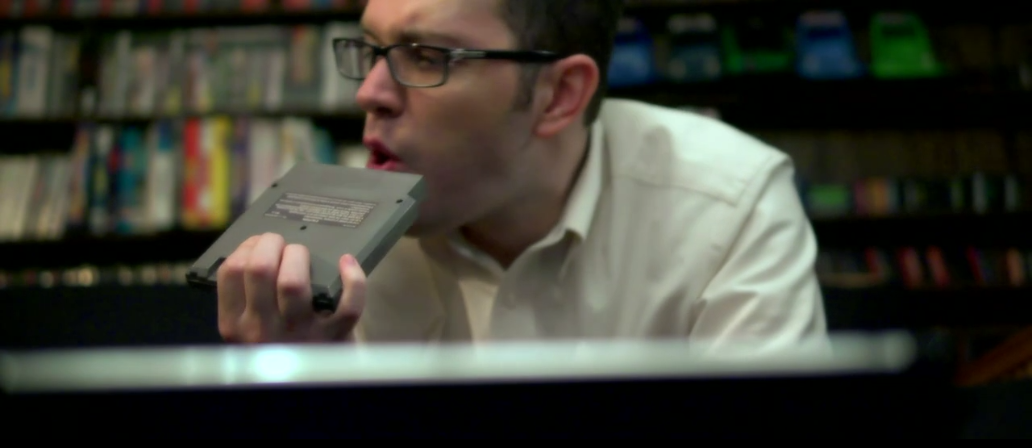

And so we have a British man whose hands we see more often than his face, talking briefly or at great length about things he already loves or has never seen before. Some episodes are informative. Some are nostalgic. Some are little more than improvised comedy routines. You never know.

People might watch James Rolfe because they like video games. People might watch Red Letter Media because they like film. People only watch Ashens because they like Ashen.

Like many YouTube personalities, Ashen grew an audience that simply wanted more of him. Unlike most YouTube personalities who fall into this category, though, he never seems particularly interested about being in front of the camera. His videos are live narrations, basically, as his hands show off whatever item is being discussed and attempt to get his camera’s auto-focus to cooperate. Ashen is in every video, and yet is mostly physically absent from them.

Again, it’s a weird channel.

Over the years, Ashen has improved his video and audio quality, but never became less content to film nearly every video in front of an increasingly battered brown sofa. What is the appeal?

The appeal is Ashen himself. More specifically, it’s the fact that he is one of the most effortlessly funny human beings alive.

This is another useful point of comparison. James Rolfe is funny, but has the benefit of working from a script; he can write and rewrite every last one of his jokes until he’s satisfied. The Red Letter Media team is funny, but it’s a team; it’s a bunch of guys, often drunk, who sit around and have a conversation, then edit out the dead air and boil each video down to the most entertaining bits.

Ashen is different.

He may — and I assume he does — come up with a few jokes or observations ahead of time, but he is clearly riffing so frequently that I am astounded at how funny he can be on the spot. It’s difficult to explain, but there are often things he could not have known in advance, and his ability to turn whatever he’s seeing into a quip that nearly always lands is uncanny.

Many people can be funny, in other words; Ashen is funny.

The man himself could read this and know that I’m talking out of my ass. (I make no claim otherwise.) But, as a viewer, that is how it appears; Ashen opens his mouth, and comedy comes out. Perhaps in reality he spends hours rehearsing and endlessly reshoots his videos to get just the right set of reactions from himself. I wouldn’t know. All I know is that it looks like he sits down, switches his camera on, and brilliance ensues.

That’s a very specific talent, and the fact that his videos are consistently good and there’s never any indication that he’s struggling to keep the jokes coming elevates him above…well, pretty much anyone else who’s ever tried to improvise.

All of which is wonderful, yes, but it leaves precious little room for a movie. Right? If video games and films were the obvious targets for our previous two entries, is Ashen associated closely enough with anything (other than himself) that could serve as the basis for a film?

Actually, yes: Tat.

While he covers plenty of deserving topics on his channel — things that are either close to his heart or close to the hearts of those in his audience — he tends to gravitate toward tat.

Trash. Pop-culture garbage. Things that don’t matter, never mattered, and can never matter. Commercial detritus. That is his area of expertise.

Several of his series and many one-off videos involve Ashen grabbing a load of junk from Wish, AliExpress, or Poundland (the equivalent of Dollar Tree here in the States) and showcasing it.

Why? Well, why not? Nobody in their right mind would care about any of these cheaply made, poorly thought-out bits of shelf (or cart) filler. They just enjoy hearing Ashen talk, and the universal pointlessness of tat makes his fixation on it all the more amusing.

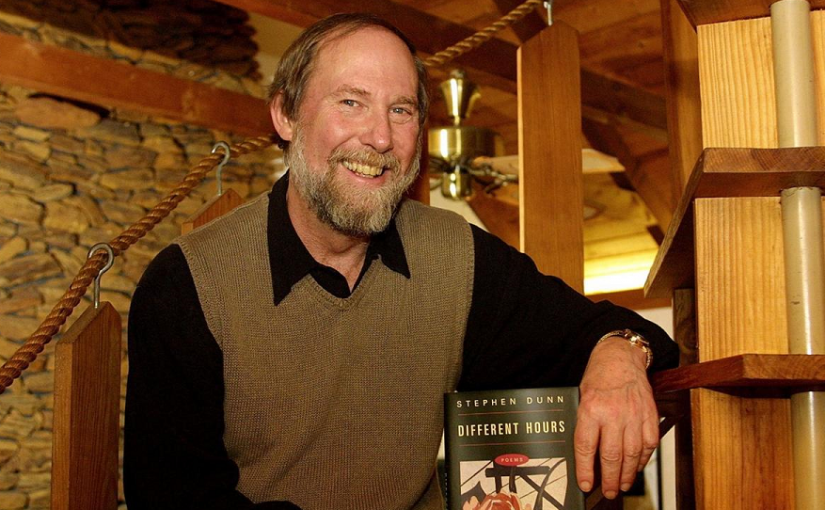

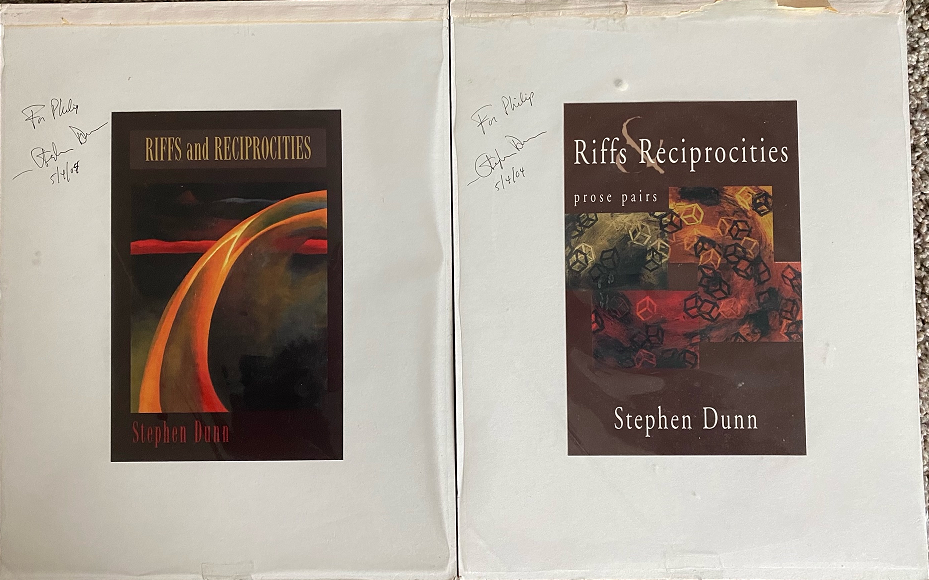

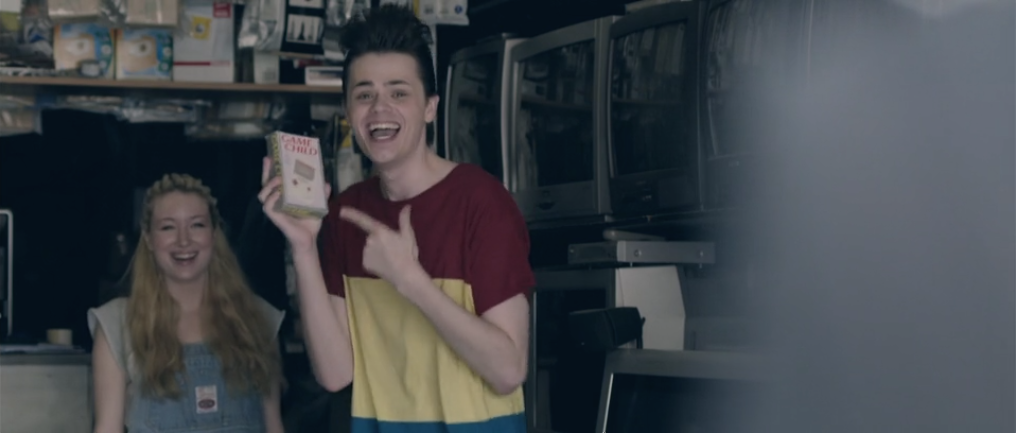

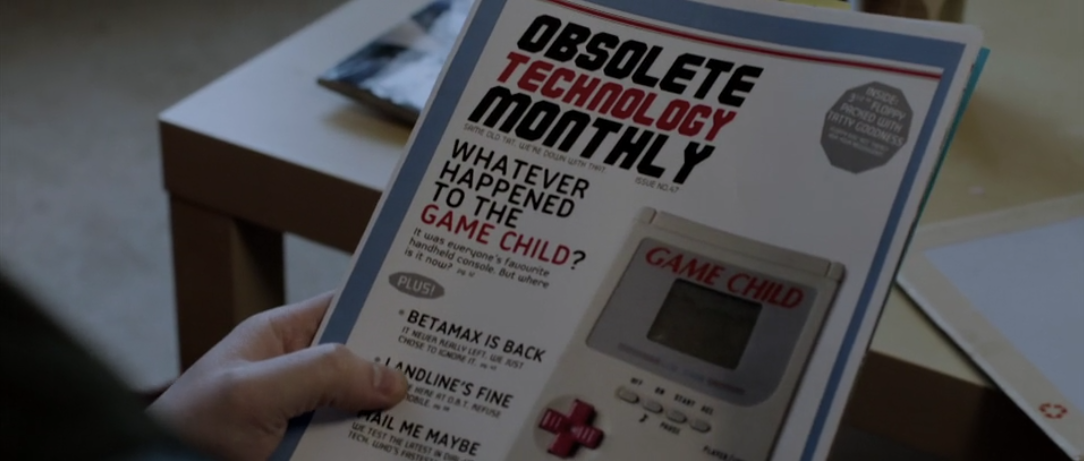

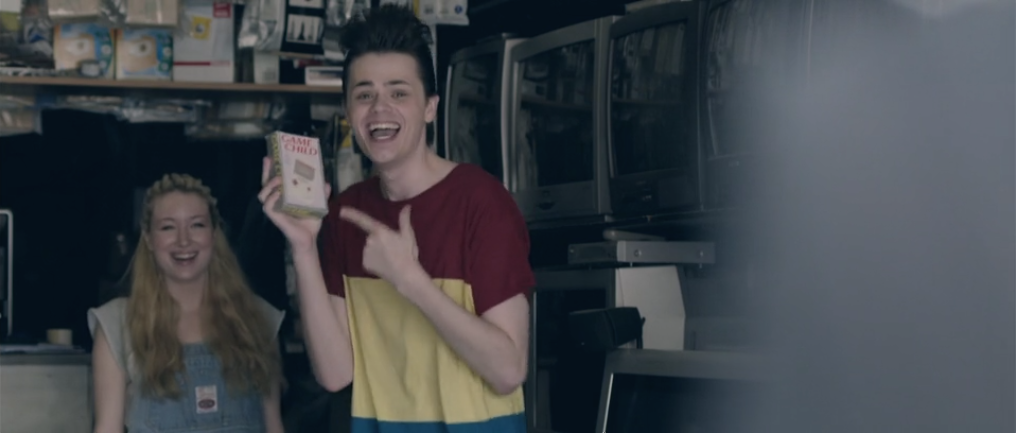

In reality, Ashen finds tat easily, either by purchasing it himself or because fans have sent it to him. This film, however, is about his mission (his character asks us not to call it a quest) to find one specific piece of tat that has eluded him since its release in 1991: The Game Child.

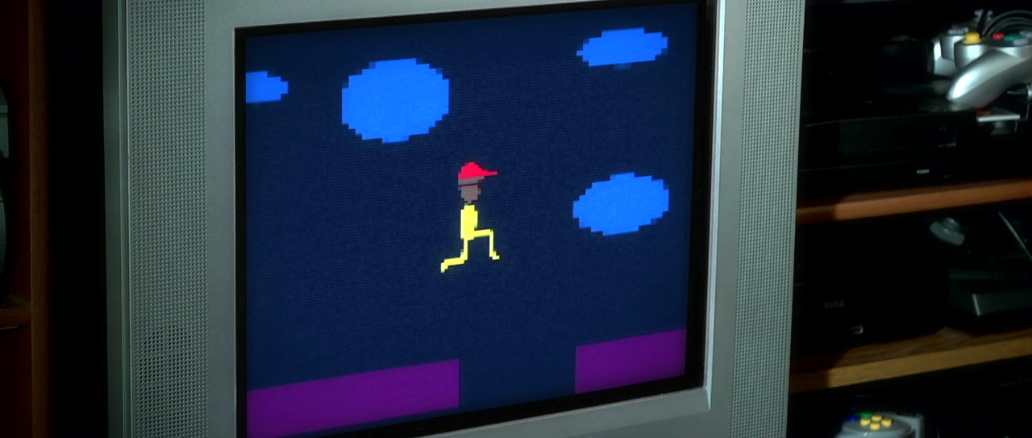

The Game Child is (or, I suppose, was) an actual product. It was released with the clear hope of confusing people who wanted to buy a Game Boy. Its branding was similar and it was built to resemble the Game Boy as closely as possible, right down to including a fake game in a fake slot and a “battery compartment” that was actually just empty space.

It had one game loaded into it, and that was it. If you wanted a different game, you’d have to buy a different Game Child, though there were only three games available. These were basic — and terrible — LCD games that made Tiger handhelds look like Symphony of the Night.

Nobody cared, because nobody wanted one. It existed only to trick people into paying for it.

Which is precisely why Ashens wants it.

“I’m a collector,” he explains early in the film. “I collect very rare but absolutely worthless collectibles.”

I have no idea how much of that applies to the real Stuart Ashen and how much of that is only the persona he uses for his videos and this film, but it almost doesn’t matter, because it feels genuine.

Ashen is an enthusiast. You’d have to be one to spend years of your life talking to yourself and uploading the resulting monologues to the internet. The difference between enthusiasts is what triggers that enthusiasm.

Is it tat, in reality? I have no idea. Ashen has a love for the early days of computer games, for classic television shows, for films old and new. Is his enthusiasm for those things more genuine than his enthusiasm for the things so profoundly without value that shops struggle to sell them? Again, no idea.

But tat is believable enough as a source of his enthusiasm. We all have our hobbies and niches. Ashens’ niche just tends to be nicher than most, which makes it at least a little more interesting by default. Whether he occupies it with sincerity or with the sole aim of entertaining others, it doesn’t matter. It is our window into Ashens.

I said when I started this year’s Rule of Three that I was interested in watching the films but hadn’t seen any of them before.

I lied to you, a bit.

Ashen uploaded this entire movie to YouTube for free at one point and encouraged folks to watch it. I think his rationale was that he’d more or less sold as many copies as he would sell, and allowing the rest of his fans to watch for free would still bring him ad revenue. It was a win-win.

I sat down to watch it, excited to see what one of the internet’s funniest people had put together for the world to enjoy.

I made it a few minutes into the film. I enjoyed none of it. I stopped watching with the best of intentions to pick it up again at a later point to see if it got better.

But I never went back. Not until this series. I couldn’t work up enough of my own enthusiasm to even click “play” again.

That was okay, certainly. Not every film has to appeal to me, and Ashen kept uploading regularly enough that I was sure that I still enjoyed his work. Ashens and the Quest for the GameChild would just be one thing that one human being created that didn’t appeal to me.

Now that I’ve watched it in its entirety, though, I think it’s just that the movie gets off to a shakier start than it should. The opening scene isn’t representative of the quality of the film to follow. The movie leads, in other words, with what is almost exclusively its weakest material.

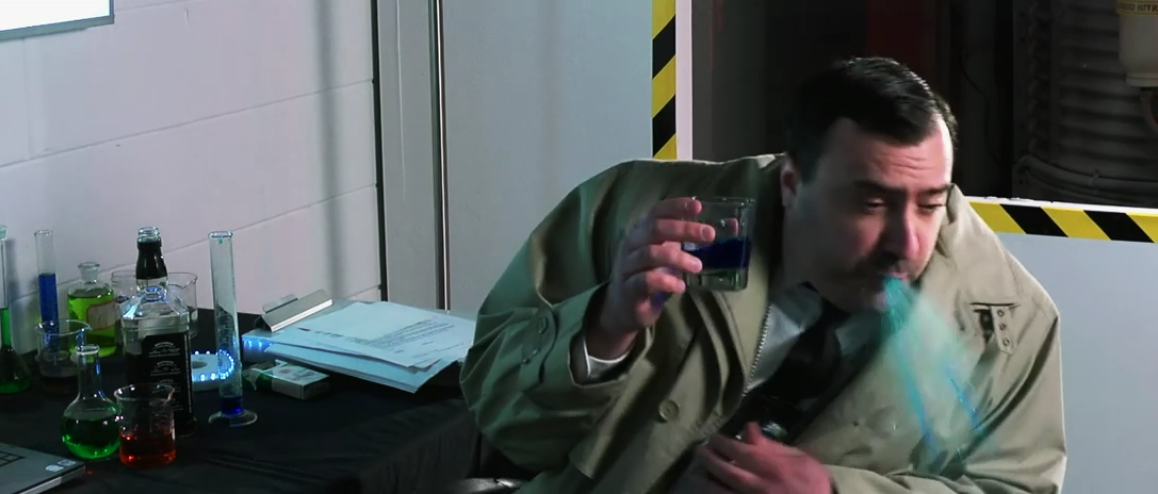

We open with Ashens and a man named Richard showing up at a corner store. They have a lead on a qMutt-17, a bootleg version of what Ashens calls a “dancing digi-dog.” (Probably for rights reasons; it seems to be the iDog.)

About to make the purchase, Ashens notices that it’s not the qMutt-17 at all; it’s the genuine, better-made, and superior in every way iDog. (“Rather than dancing,” Ashens says of the qMutt-17, “it simply emitted a series of loud beeps and then fell over.”)

That’s funny. In concept, it’s a perfect opening for the film. It both establishes what interests Ashens as a character and serves as a good joke: He gets angry that someone is not selling him inferior merchandise.

It fails in a few places, though, some of which will run through the entire film.

Firstly, Richard. I have nothing against the actor — Richard Sandling, who seems to have done pretty well for himself — but I have no idea what the purpose of his character is.

He’s…here, certainly. Then he does nothing of value, in terms of helping Ashens. His uselessness does tie into Ashens proclaiming that he prefers working alone, but since the next time we see him “working” at all he’s taken on a new sidekick, this can’t be the reason Richard exists.

As the film unfolds, there’s a running joke / subplot about Richard in Ashens’ kitchen, where he hosts a party, I guess? Then at the end he shows up glowing like a Star Wars force ghost. Ashens assumes he’s dead but instead he just has radiation poisoning. That…actually does make more sense than it probably seems here, but the point I’m making is that, narratively, he serves no purpose, and yet keeps showing up.

I suspect there might be a kind of in-joke at work here that I’m not privy to. A number of Ashens’ real-world associates show up here (and in the excellent sequel, Ashens and the Polybius Heist); my assumption is that the two men overlap in some real-life orbit and this is a reference to that. The weird thing is that this doesn’t happen anywhere else; every other character serves enough of an in-film purpose that we don’t need to worry that we’re lacking information from outside the film.

Secondly, while Ashens conducts his business in a seedy back room, Richard hangs out in the shop area. This happens a few times throughout the film; Ashens keeps the plot moving in one sequence, and we keep cutting back to one of his hangers-on doing…something in a concurrent sequence. They never really overlap in any kind of thematic way or inform each other; we simply keep cutting from the main action of the film over to whatever a less-important character is getting up to. It’s never anywhere near as funny, interesting, or important as whatever Ashens is doing himself, so it’s a puzzling pattern.

Beyond that, there’s an issue that is (thankfully) exclusive to this scene. Mawaan Rizwan plays both the man Ashens in here to see and that man’s mother. No intended disrespect to Rizwan, but it’s a little uncomfortable to see him in drag with an exaggerated East Indian accent when his other role is…just sort of normally, inoffensively funny.

I think there’s an element of intended humor behind the mother being an obvious man in woman’s clothing, with the comedy accent meant to heighten our response, but really it feels like a poorly considered scene from a 1970s sketch show that didn’t know any better.

And, okay, fine, as long as I’m complaining at length about a few minutes’ worth of material, Rizwan wears what is obviously a fake mustache in his scene with Ashens, and that’s okay. But later in the film another character wears an obviously fake mustache, and the fact that it’s obviously fake is acknowledged as a joke. So why isn’t it acknowledged here? Am I meant to believe that this obviously fake mustache is real within the world of the film but a different, equally obviously fake mustache later in the same film is not real? IT IS MADNESS

All of this and a few flat jokes put me off watching the rest of Ashens and the Quest for the GameChild for a long time. Imagine my surprise when I finally did see the rest of the film and realized how much of an outlier this opening sequence is.

Last week we covered Space Cop, a film I am told was in various levels of production between 2008 and 2015. If I were so inclined, I could probably watch that movie again, keeping that fact at the front of my mind, and look for all of the little indications of a movie that was assembled over such a long period of time. I could watch for hair length, tweaks to the costumes, facial hair…all stuff that doesn’t matter, but which will be preserved to some degree simply because time passes and things change.

I have no way of knowing if Ashens and the Quest for the GameChild were also filmed over a long period of time, or if perhaps the script were written over the course of years, or anything else, but it certainly does seem like the opening scene came from a different era of intention than the rest of the movie. It looks the part, but it feels and plays like a deleted scene that for some reason we’re being shown before the film starts.

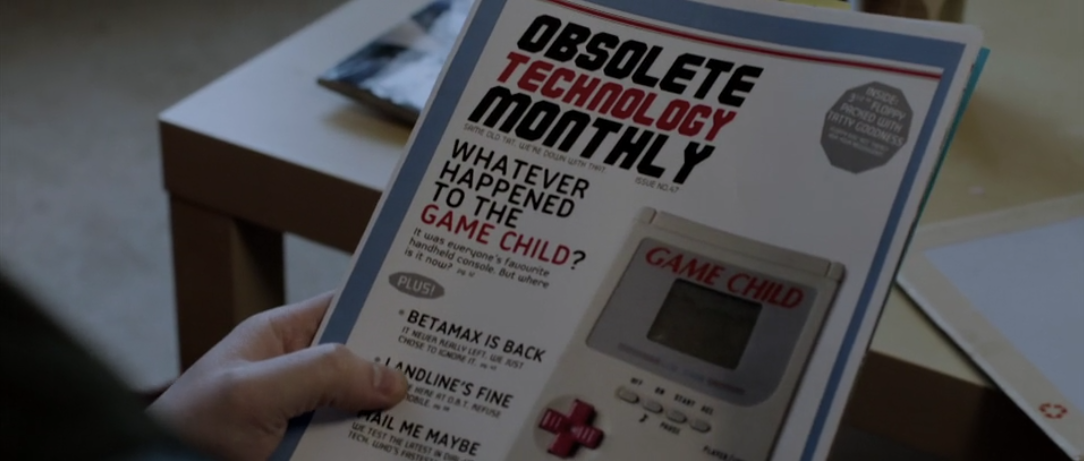

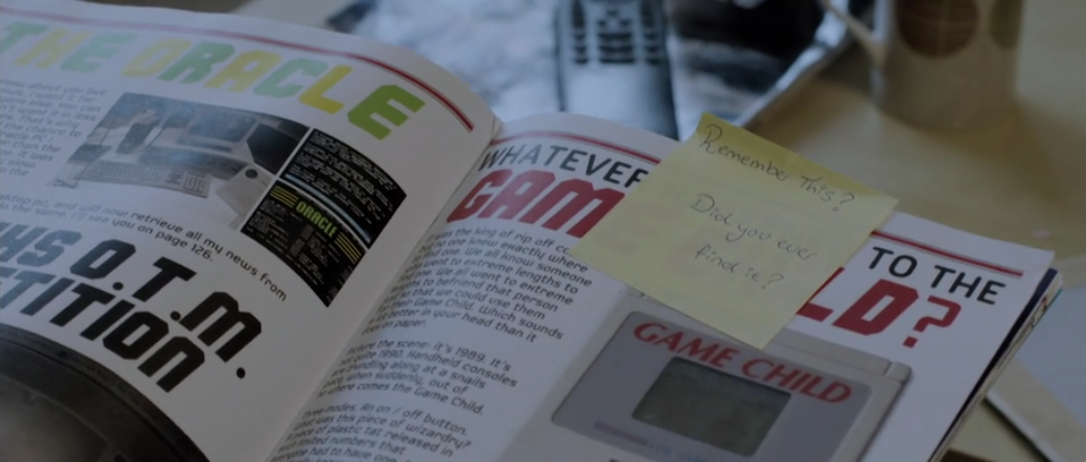

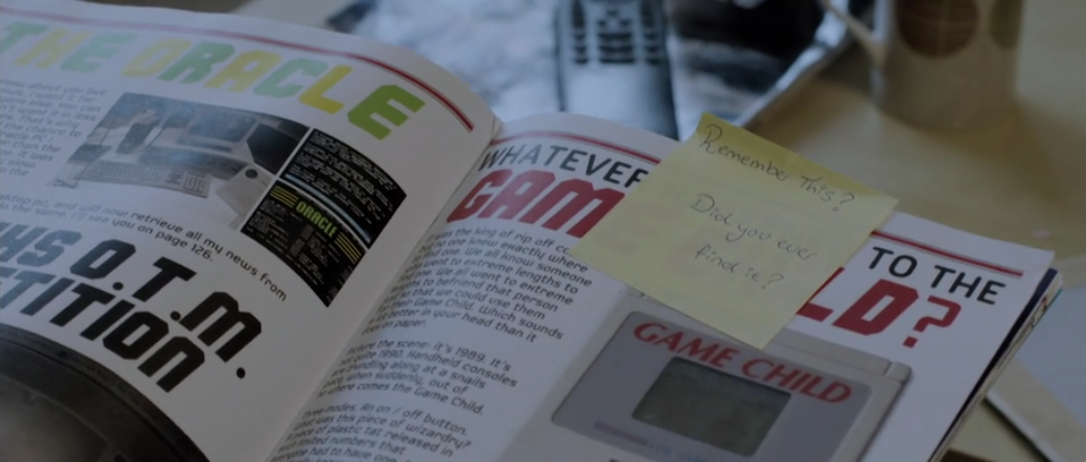

The movie proper kicks off when Ashens reconnects with an old acquaintance at around the same time he mysteriously receives a copy of Obsolete Technology Monthly in the mail, with a sticky note flagging a feature about the Game Child.

It turns out that the Game Child is Ashens’ white whale. He has a place of honor for it in his tat dungeon, but has never been able to get his hands on one, due to the fact that the system’s distributor — The Terrifically Good Company, within the reality of this film — bought the disappointing handheld back for more money than customers paid for it.

We also learn that upon its release in 1991, Young Ashens attempted to buy the lone unit shipped to Norwich, only to have been beaten out by his nemesis, Nemesis.

It’s a funny setup, and indeed the entire film builds to an absolutely perfect punchline…but we’ll get to that.

For now, this early in the film, it’s mainly amusing to me that Young Ashens already loves tat. It’s one thing to be a grown man reading a copy of Obsolete Technology Monthly and wondering if he could get his hands on some historical consumer oddity, but it’s another that Young Ashens was already anticipating the release of a disappointing knockoff and intended to visit the shop that very morning to buy it. That’s cute.

At the behest of his newest enthusiastic sidekick, Ashens sets out to find and obtain what is likely the last remaining Game Child under public ownership.

That’s the plot of the film, and it’s basically what I thought Angry Video Game Nerd: The Movie would have been: a picaresque. I know I should probably say “road movie” instead, but Ashens never seems to get far beyond Norwich. In terms of scope, then, it has more precedent in literary than cinematic tradition. It’s James Joyce’s Ulysses more than it’s Pee-wee’s Big Adventure.

As with Ulysses, Ashens explores a world that is small and already familiar to him, interacting in large part with people he already knows. The adventure unfolds over a narrow and familiar landscape. Not dear, dirty Dublin, but perhaps near, nerdy Norwich.

Each of the films we covered this year have some degree of on-screen celebrity talent. Ashens and the Quest for the GameChild almost certainly handles it best, but I honestly feel that all three movies at least handled it well.

Angry Video Game Nerd: The Movie had a great, unhinged Eddie Pepitone, as well as a fun appearance from Lloyd Kaufman. If you’d like to count it, Howard Scott Warshaw — the real-life programmer behind E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial — also popped up as himself. He didn’t do or say anything noteworthy, but at least the film’s “look who we found!” moment was brief.

Space Cop had Patton Oswalt as its big get. We discussed last week the issues with that, but its other two winking cameos were far better. Comic artist Freddie Williams appears in the bar scenes, but isn’t treated as a celebrity; he just gets to be understandably baffled by Space Cop, who is exactly as baffled by the concept of solitaire. Then there was B-movie auteur Len Kabasinski, who served as a humorously obvious stunt double for Space Cop. If you recognize him, you get a nice little chuckle of familiarity. If you don’t, the completely different build and dangling ponytail sell the joke perfectly well on their own.

Ashens and the Quest for the GameChild has two major celebrity cameos, and they both work perfectly because they don’t feel any different from the rest of the actors. You’re likely to recognize them, but they don’t distract. They fit.

First, there’s Red Dwarf’s Robert Llewellyn, playing Ashens’ old professor. Before Llewellyn will share any knowledge of the Game Child’s whereabouts, he requires Ashens to defeat him at “the most intensive game of skill and wits ever devised by the human mind.”

It is, of course, the head-to-head children’s game Space Attack!

Llewellyn is predictably great, but it never feels as though the movie is reveling in his casting. It’s a role a number of actors could have played brilliantly, and one of those actors is Robert Llewellyn who, fortunately, happens to have gotten the part. It even ends with Ashens giving him a noogie, perhaps the polar opposite of Red Letter Media being unable to bring themselves to interrupt Patton Oswalt’s overlong spotlight.

The bigger celebrity in this film is Warwick Davis, who plays himself. Granted, most people watching the film will already know Davis, but even if they don’t, his scene here is funny enough on its own.

Davis is revealed to be the actor behind the mask of another character, which confuses Ashens, as that other character is much taller.

“I’m an actor,” Davis tells him flatly. “It’s called acting.”

The scene contains some excellent back and forth between the two, as Ashens fishes for some logical explanation without accidentally coming across as bigoted, and the perfect editing of the scene allows a small man to become a much larger one in the space between a change of camera angles.

It’s a fantastic sight gag paired with Monty Python-worthy dialogue between two people on opposite ends of an unbridgeable absurdity. Davis is perfect here, but I don’t know if the scene is any funnier because we recognize him. The film doesn’t lean on him to make the scene work; the scene works and we get to spend some time with Warwick Davis. (Never a bad thing.)

Llewellyn and Davis are two of the many characters with whom Ashens crosses paths on his way to find the Game Child. Each new character requires Ashen to come up with a completely new idea and dynamic that will keep the film moving and also be funny. That’s something even accomplished filmmakers could struggle with. Ashen doesn’t; the film stays consistently amusing in a way that feels — like Ashen’s comedy in general — effortless.

It’s worth noting here that Ashen, of the stars of this year’s films, seems to be the most comfortable in front of the camera. That…might be difficult to articulate, as neither Rolfe nor the Red Letter Media crew seem uncomfortable; it’s more that Ashen comes off as much like himself here as he does in his videos.

As odd as it may sound, Ashen feels so at home within the insanity of this film’s world that it’s easy believe that this is his world. That when he finishes reviewing some piece of garbage action figure, he turns off his camera, opens his front door, and finds himself in this precise version of Norwich that registers to us as insane but — necessarily — feels to him like home.

There’s a kind of innate affability to Ashen, which allows his dry sarcasm to carry him further into our good graces than it would otherwise. Admittedly, Ashen has English blood coursing through his veins, giving him a preternatural fluency in dry sarcasm, but it’s a skill the man has clearly honed over the course of a lifetime.

There’s a reason he keeps getting compared to Simon Pegg — a real-life running joke that, almost inevitably, finds itself a home within the film — and it goes beyond whatever degree of physical similarity the two men have. It’s because Ashen is a gifted comic, whether or not he’d even refer to himself that way. (I’m not playing coy, here; I genuinely have no idea how Ashen would refer to himself.)

The fact that he plays himself — “himself” — in this film also complicates things just a hair when compared to the previous two movies we covered. The AVGN can ogle a woman’s tits in a bar and that doesn’t mean that James Rolfe himself does that. Space Cop was a man who looked like Chris Farley but saw Jean-Claude Van Damme whenever he looked in the mirror, but that doesn’t mean Rich Evans is anywhere near that delusional.

Ashen, though, blurs the line. When his character does something intelligent, doesn’t that mean we’re supposed to see Ashen himself as intelligent? When his character is a dick, aren’t we supposed to see Ashen as a dick?

I’m not totally sure. At the very least, Ashen paints (and plays) his character here as both realistically clever and realistically flawed. He neither comes across as a celebration of himself nor as some exaggerated condemnation of his own (or his character’s) flaws.

He’s smart enough to track down the Game Child, but not smart enough to realize he’s been betrayed, which in itself was a result of his dismissiveness toward the sidekick who looked up to him. Then there’s…

Well, there’s women.

The film introduces two major female characters in Ashens’ life. One is Ashley, an old flame who had an affair with Llewellyn. Ashens was understandably hurt by this, but never to the point that it becomes a “poor me” situation. He doesn’t revel in his sadness; it’s just, realistically, something that hurt him a long time ago.

It would still be easy to hear about this and feel bad for the character — backstory like this could easily be used to define how the audience should respond to him — but it’s balanced out by Marian.

Marian, a librarian, is another of Ashens’ exes, who quite clearly still carries a torch for him. In their relationship, she is the one who got hurt. What’s more, we know for certain that her grievances are well-founded; Ashens indeed uses her and manipulates her emotions so that he can chase down leads on whatever tat he’s trying to find now. He does it during this film to find the Game Child, lying that she can join them on their mission. The moment her back is turned, he flees without her.

It’s interesting. Ashen could paint himself as some kind of womanizing rogue — humorously or seriously — but he comes across instead as an identifiably damaged person. He’s been hurt emotionally, and while it’s fair to say that he’s gotten over it, he hurts others emotionally along the way to what he wants.

Is that a result of the pain of his previous relationship? Is it coincidental? What matters, I think, is the fact that Ashens doesn’t seem to realize he’s doing it. Ashen the writer and actor surely does, but Ashens the character never seems to have a full understanding of the way in which he treats others, or how he makes them feel.

He’s not a jerk, or a bully, or a hero, or a saint. He’s just a person. He’s realistically flawed and the movie doesn’t ask you to pity those flaws. In a movie that’s technically a vanity film, that’s an achievement in itself.

Vanity films, by their nature, are meant to showcase their stars. Let’s not pick on anybody, but if you’re even passively interested in film, you’ll be able to name movies that exist only to show off the talents — often theoretical — of the filmmaker. They cast themselves as the handsomest or most beautiful characters in the film. The smartest. The wittiest. The strongest. Other characters speak some variation on “Raymond Shaw is the kindest, bravest, warmest, most wonderful human being I’ve ever known in my life,” only without the intent of sending shivers down the audience’s spines, as in The Manchurian Candidate. We’re meant to actually believe it.

And so when Ashens wins a fistfight against Nemesis, it’s neither because Ashen plays the character as being all that strong or all that clever; he just refuses to approach the man who has taken a crane stance.

Ashen is showing off, sure, but he’s showing off in the way I wish all vanity filmmakers would show off: He’s showing off his writing talents. His talent as a humorist. His understanding of pacing and editing and structure. At 90-ish minutes, it’s the shortest of the three films we’ve covered this month, and it’s also the one that feels the least bloated, not coincidentally.

Without question, Ashen had more material than he could fit into 90 minutes. Unlike the other two films, however, this one is edited down to its strongest stuff rather than swollen into weakness. It’s the earliest of the three films, and yet it feels like it could have been made in direct response to them. “Here,” it seems to say. “Let me show you how to take what you did, and turn it into a movie.”

Ashens and the Quest for the GameChild also looks and sounds the most like an actual film. Damning with faint praise, I know, but let me say that I’m more than willing to give James Rolfe and Mike Stoklasa and any other amateur filmmaker as much leeway as necessary when it comes to production.

If I can see what’s happening and hear what characters are saying, I’m on your side. I know you don’t have a Hollywood budget or pricey equipment. I know you’re relying on favors from friends, doing this in whatever free time you can scrape together, using whatever props you have laying around. I know you are doing your best with what you have. I know that and I sincerely admire you for that.

And yet this movie looks great. I don’t know what demon Ashen traded his soul to, but it may have been worth it. It’s the slickest and most professional of the three productions by far, to the point that I don’t even feel the need to make allowances for it being independently produced. I’m sure Ashen himself deserves plenty of the praise for this achievement but, good lord, let me extend that praise to anyone else involved with this film. Its presentation is beyond what any of us should expect from a little YouTube movie like this.

Right, okay, the plot. Forgot about that.

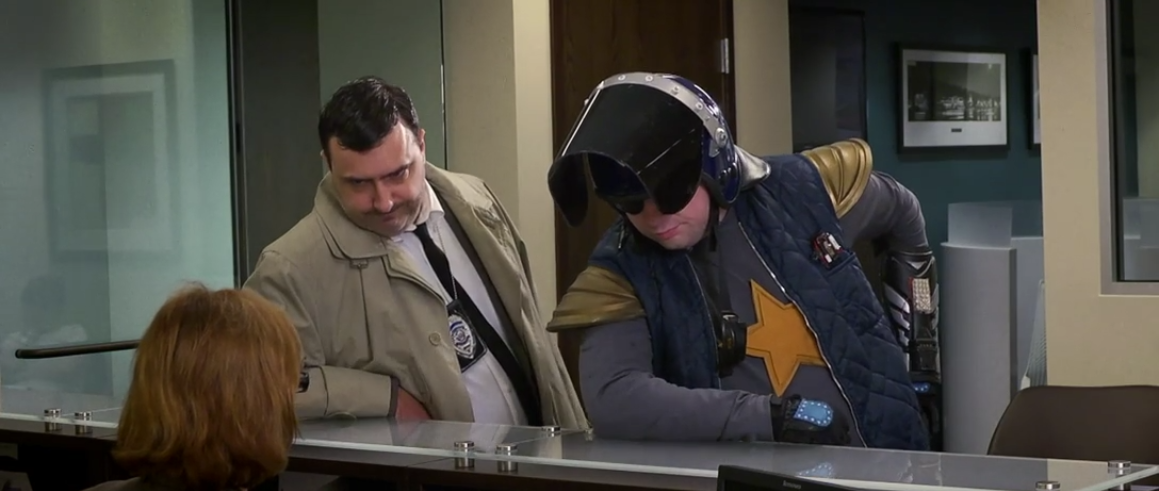

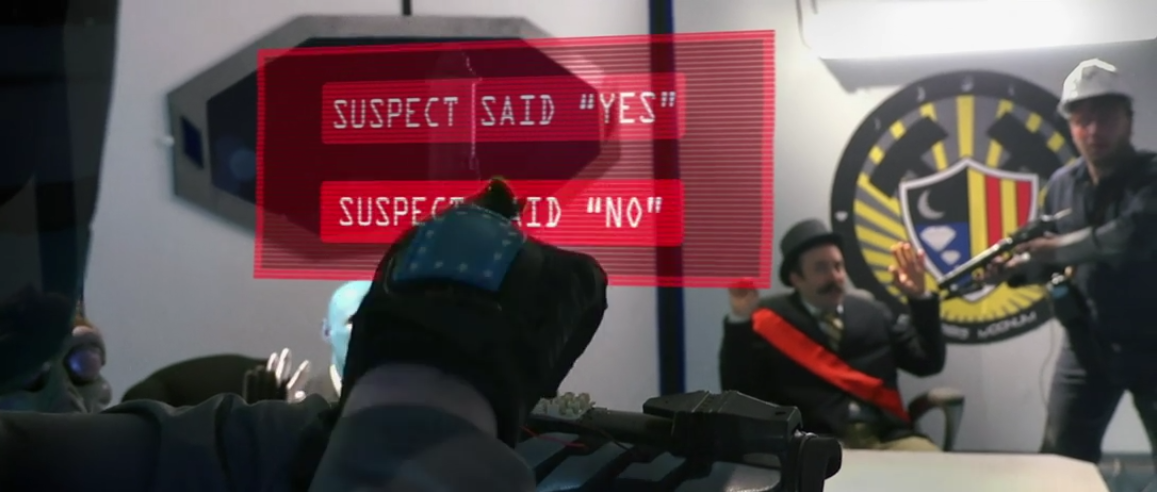

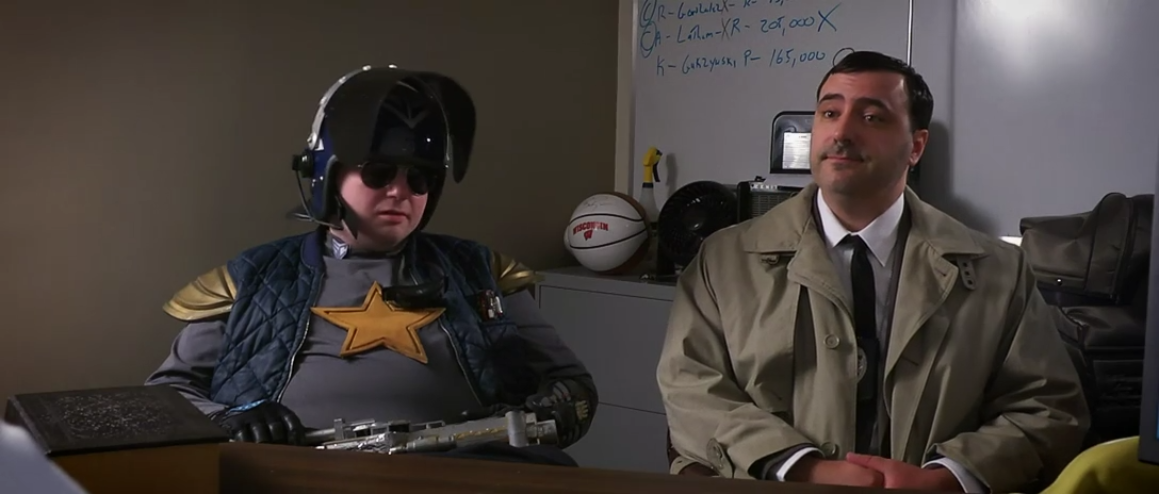

Ashens’ quest — sorry, mission; I keep doing that — leads him from misadventure to misadventure, my favorite of which featured Norwich-based amateur superheroes Knighthood and Decoy.

If these two are a reference to something (beyond real-world costumed vigilantes in general), I’m not aware of it. And yet it’s one of the funniest sequences in any of these movies.

The two pull up beside Ashens on the street and stuff him into the car on the grounds that it’s a dangerous area. (The fact that they drive a two-door sedan and one of them needs to get out in order to let Ashens in is hilarious, though probably just a result of having to use whatever vehicles they could get when shooting the film.)

“A lot of weirdos around here, my friend,” Decoy cautions/lectures Ashens. Then, “We’ve been beaten up in that alleyway just there.”

“Five times,” Knighthood interjects.

I could basically just transcribe the entire scene, but I’m trying to leave as many good jokes unspoiled as possible. (That applies to all three of these films, by the way; if you think one of them sounds interesting, don’t assume that I’ve spoiled any of their best material.)

It stands in strong contrast with Angry Video Game Nerd: The Movie. There, Rolfe had some jokes he wanted to make about kaiju films, and twisted his project around until he could (barely) get them to fit. Here, Ashen had some jokes he wanted to make about superheroes, but he rooted them in the reality of his film.

Knighthood and Decoy don’t fly or have laser vision, because those things don’t exist within the world of this movie. Instead they’re a pair of recognizable — if eccentric — boobs. It’s all the funnier for the fact that it has a place within identifiable reality. Stretch too far to make a joke and it’s no longer impressive that you made it; weave that joke into a narrative and you’ve got a reason to be proud.

The characters are great, as they’re clearly trying to present themselves as superheroes but, once they are in that position with someone, they have no clue what to do next. They’ve only thought this through as far as it took to envision themselves in costume. It’s marvelous.

The movie climaxes at the headquarters of The Terrifically Good Company, where Ashens finds what may be the last Game Child remaining in circulation.

It’s here that he learns the dark secret of the knockoff Game Boy.

“When assembled together correctly, the Game Child makes a nuclear bomb,” Ashley tells him.

It was the result of a deranged factory employee, and the distributor did not notice the plutonium stashed away in every Game Child until the units were already on shelves. The company recalled them, of course, but not all of them came back. And Ashley attempts to force Ashens, at gunpoint, to figure out how to arm to device.

The Game Child, it turns out, is not an easily dismissed hunk of plastic; it actually represents a previously unknown, fascinating, potentially fatal chapter in the annals of history. Which means…well…

“You told me that this is special, and of immense value,” Ashen says to her. “Things of worth are worthless to me.”

And then he destroys the Game Child.

It’s the perfect punchline not only to the film, but to Ashens as a character and as a channel.

The more genuinely interesting something is, the less this man cares about it. If it isn’t junk, he’s not going to spend an hour talking about it in front of his sofa. If it has any significance to the world around him at all…well, what’s the point?

It’s brilliant and — impressively — it’s not just a big joke with which to draw the film to a conclusion; it’s the perfect joke.

What’s more, it works as a conclusion to the character’s arc. “Things of worth are worthless to me” goes one hell of a long way toward explaining his difficulties with relationships, with friendships, with meaningful human interaction. It’s both a conclusion to the Quest for the Game Child and an understanding — and an explanation, and an admission — of why the character was on that Quest to begin with.

Letting go of the Game Child also — and brilliantly — frees up his hands to hold on to something important.

What is that? Or, rather, what will it be? It doesn’t matter, really. What matters is this moment of change, played completely within the bounds of a story about a funny man tracking down a piece of consumer electronics trash.

It’s pretty fucking excellent.

Both of the other films we covered this year have left a bit of a stain on their creators’ legacies. For Rolfe, the accusations of theft and dissatisfaction with his latter-day output have yet to leave him. Space Cop was received so poorly that Red Letter Media jokes about the film’s failures and shortcomings far — far — more often than they promote it.

Ashens and the Quest for the GameChild, however, didn’t seem to have a negative impact on its creator at all. I’m sure there were those who were disappointed by it — this is the internet, of course — but any disappointment here was easily enough separated from whatever the audience felt about the man behind it.

That might be an unexpected byproduct of this being the one that looks and functions the most as a film in its own right. It’s not an extension of the channel; it’s something with its own merits that can either be celebrated or derided. It’s a complete work of fiction that stands or falls on its own, and isn’t beholden to whatever affection it expects us to have for Ashen himself.

Because he made an actual movie, in other words, that movie gets to absorb the praise or the blame. Ashen himself is still Ashen, himself.

In real life, Ashen got a hold of a Game Child (likley quite easily) and did indeed review it on his channel after the release of the film. It’s junk. It was perfectly at home in front of that brown sofa, in those hands, being spoken about by that voice.

Those who wanted to see what Ashen could do with a feature-length motion picture got to find out. And those who just wanted Ashen to talk about a forgettable shitty handheld in his standard style got that, too. Everybody won. Or, at the very least, nobody had any reason to be disappointed.

When I started this year’s Rule of Three, I expected all of the movies to be at or around the same quality of Angry Video Game Nerd: The Movie. And I was okay with that. I liked — and like — Rolfe as a human being. I have affection for his output and I have no reason to think he’s anything other than an excellent person. His movie wasn’t great, but that was okay. My movie probably wouldn’t be great, either.

Then Space Cop and Ashens and the Quest for the GameChild both turned out to be really good. (In profoundly different ways, mind you.) They were each successful in what they set out to do, and any disappointment would have to come from the fact that they were doing things other than what an audience might have wanted.

My intention this year was to celebrate the histories of three of YouTube’s biggest success stories. I figured that the movies would simply be quirky offshoots that were worth discussing enough to justify the spotlight. That really only ended up being the case with the first film. The other two stood on their own better than I ever could have expected them to.

I’m not sure which of the three is my favorite. Gun to my head, I’d probably go with Space Cop. But Ashens and the Quest for the GameChild is the best of them, certainly. And while I’m absolutely sure it was a pain in the ass to make, it feels effortless, just like everything Ashen does.

Bringing us a 90-minute feature film feels no more difficult than recording some junk in front of an old sofa.

That’s one hell of an impressive illusion.